Introduction

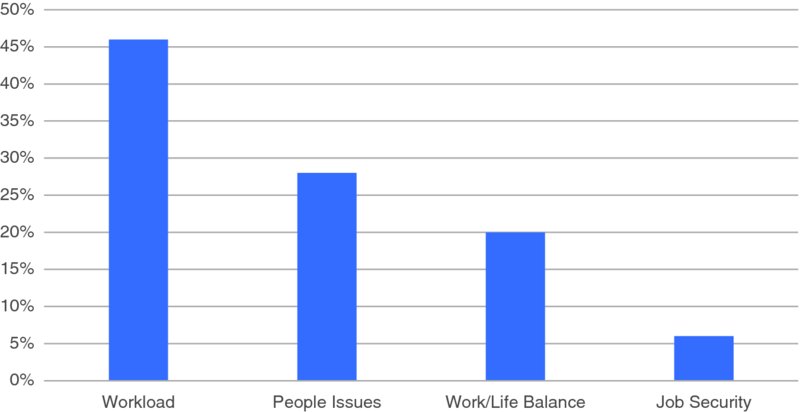

As the world changes around us with technology becoming more and more integrated into our lives, our need for human interactions only increases. Many of us are old enough to remember the days when personal computers first came onto the scene. We were promised that they would save us so much time we could start planning shorter work weeks, longer vacations, and sabbaticals. With the introduction of the Blackberry (remember that?) and the iPhone, the workday suddenly extended into our evenings, nights, weekends, and vacation time. We now know that technological innovations don’t always work out quite the way their creators thought they would. Nor do they have the anticipated effects. Not only are we living through a technological revolution, we live in a new age of information. For example, we know more about mental health and psychology now than we’ve ever known in history. The number of scientific papers being published in mental health alone is staggering. There are currently 525 scientific journals publishing thousands of articles just on this topic. If you search Amazon.com you can find over 60,000 books related to mental health. And these numbers are growing all the time. Yet, with this explosion of knowledge about mental health and the increased availability of technology, we still haven’t been able to take control of our problems. In fact, in many ways, things have gotten worse. For example, we’ve seen dramatic increases in the negative effects of stress. Research reported by the American Institute of Stress shows that on-the-job stress is far and away the major source of stress for American adults. As well, it has escalated progressively over the past few decades. Increased levels of job stress, as evaluated by the perception of having little control but lots of demands, has been found to be associated with more heart attacks, hypertension, and other disorders. Some sobering statistics on stress at work were reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. In one survey 40% of workers reported their jobs were “very or extremely stressful.” Another survey found that 26% of workers reported “often or very often being burned out or stressed by their work.” And a third, Yale University survey, reported that 29% of workers felt “quite a bit or extremely stressed at work.” With regard to our progress in the information/technology era, 75% of employees believe that workers have more on-the-job stress than a generation ago. Not only do these numbers translate into huge losses to the economy, but they take an enormous human toll. An estimated one million workers are absent every day in the US due to stress. It’s also been reported that absenteeism is estimated to cost large American companies an average of $3.5 million a year. One large corporation found that 60% of employee absences could be traced to psychological problems that were due to job stress. What are some of the causes of workplace stress? One survey found the following breakdown: 46% due to workload, 28% due to people issues, 20% due to juggling work/personal lives, and 6% due to lack of job security (American Institute of Stress, 2006) as seen in Figure I.1. How manageable are these issues? In this book we explore ways in which you can better manage yourself and some of these situations. Our hope is that the information and methods that we provide can help you lead a more fulfilling and less stressed out life. Figure I.1: Causes of Workplace Stress In this book we introduce you to the new (well, 30 years old), little known concept of hardiness. Hardiness is composed of three facets—commitment, control, and challenge. These facets work together to provide a kind of mental shield, helping people to stay healthy and even excel in the midst of stress and change. We’ll be discussing these elements throughout the book. How did we come upon this concept? Paul did his doctoral thesis on this topic over 30 years ago. After learning about how senior executives reacted in a wide variety of ways to the same news about a merger involving their organization—some got extremely stressed out and others were excited about the challenge—he got interested in this phenomenon. For his doctoral dissertation he wanted to see how stress played out with a working-class group of people—city bus drivers. Sure enough, there are wide differences in how bus drivers react to basically the same stressful situations. As often happens in psychology, in order to study psychological factors, we need to develop measures that can capture them as best we can. Without validated measures we’d just be talking about theories, ideas, and opinions. While these are all useful starting points, we don’t really know what’s real until we can measure it and validate it. So, we can give you all kinds of theories about stress and how to manage it, but without documented research, it’s merely a set of opinions. Paul continued his distinguished career in the military investigating hardiness, eventually reaching the rank of Colonel and teaching at the West Point Military Academy. As part of this endeavor, Paul developed a tool to help measure hardiness. In order to understand hardiness and its effects on people, it’s important to measure it. The tool was originally called the Dispositional Resilience Scale (DRS), which evolved into the DRS15-R after years of research. Now, the instrument has been revised and further improved with large normative samples and greater applicability. The current tool is called the Hardiness Resilience Gauge (HRG). It is the years of research using this instrument that has helped inform much of what we have learned about hardiness. Many of the studies we talk about in this book have relied on this hardiness measurement tool. There are many practitioners who have been certified in the use of the HRG around the world. To connect with one of these practitioners, simply contact us at [email protected]. To learn how to become a certified user yourself of the HRG, you can contact us at the same email address. Meanwhile Steven has been involved for over 25 years in establishing and expanding our knowledge in the area of emotional intelligence. Being one of the pioneers in developing and escalating the use of the world’s most widely used scientific measures of emotional intelligence (the Emotional Quotient Inventory 2.0 or EQ-i 2.0 and the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test or MSCEIT), he has long been interested in factors that lead to emotional health. The hardiness factor, related to the stress tolerance element of emotional intelligence, is a perfect fit to continue this work. In this book we use many real-life and some fictional examples of people and situations to illustrate our points. For the real-life examples we used people’s full names and, when we included their hardiness scores, we obtained their permission. For the fictionalized accounts we tended to use examples of people we’ve known, but with made-up names and slightly changed details so they wouldn’t be recognizable for confidentiality purposes. We hope that the information, research, case studies, anecdotes, and exercises in this book will help make stress something that works for you (by developing a hardiness mindset) and will help you achieve your life goals. Steven J. Stein, PhD Paul T. Bartone, PhD