Chapter 10. Comparable and Enumerable: Ready-Made Mixes

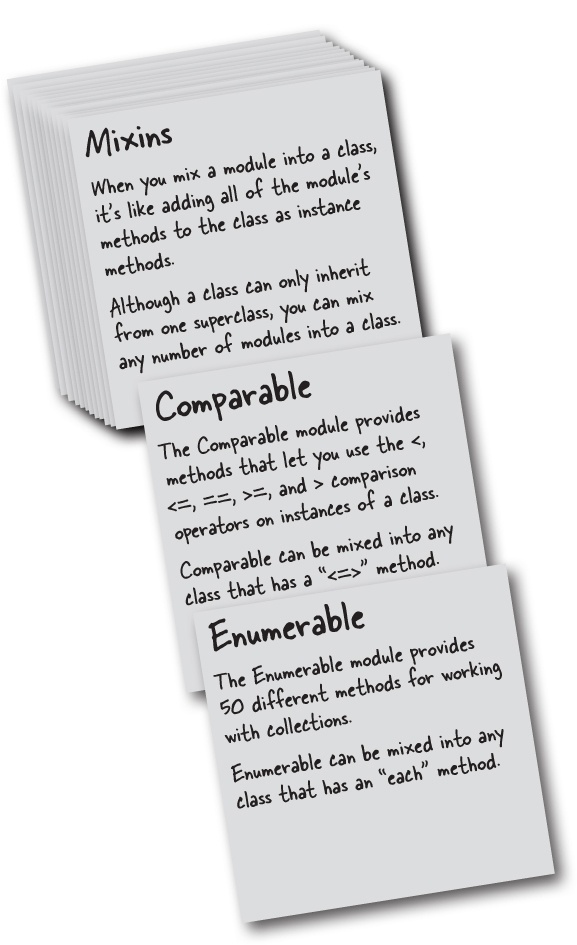

You’ve seen that mixins can be useful. But you haven’t seen their full power yet. The Ruby core library includes two mixins that will blow your mind. The first, Comparable, is used for comparing objects. You’ve used operators like <, >, and == on numbers and strings, but Comparable will let you use them on your classes.

The second mixin, Enumerable, is used for working with collections. Remember those super-useful find_all, reject, and map methods that you used on arrays before? Those came from Enumerable. But that’s a tiny fraction of what Enumerable can do. And again, you can mix it into your classes. Read on to see how!

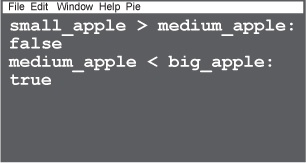

Mixins built into Ruby

Now that you know how modules work, let’s take a look at some useful modules that are included with the Ruby language...

Remember comparing numbers using <, >, and == in the guessing game in Chapter 1? You may recall that comparison operators are actually methods in Ruby.

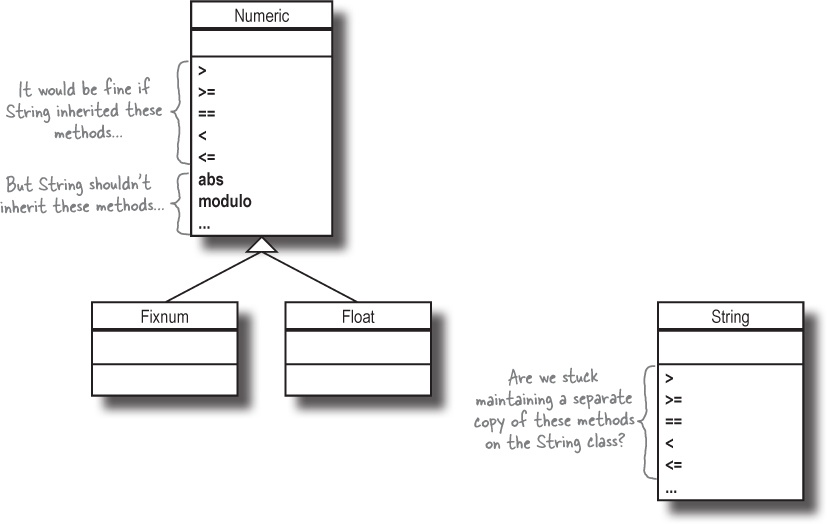

All the numeric classes need comparison operators, so the creators of Ruby could have just added them to the Numeric class, which is a superclass of Fixnum, Float, and all the other numeric classes in Ruby.

But the String class needs comparison operators, too. And it doesn’t seem wise to make String a subclass of Numeric. For one thing, String would inherit a bunch of methods like abs (which gives the absolute value of a number) and modulo (the remainder of a division operation) that aren’t appropriate to a String at all.

So we can’t really make String a subclass of Numeric. Does that mean Ruby’s maintainers have to keep one copy of the comparison methods on the Numeric class, and duplicate the methods on the String class?

As you learned in the last chapter, the answer is no! They can just mix in a module instead.

A preview of the Comparable mixin

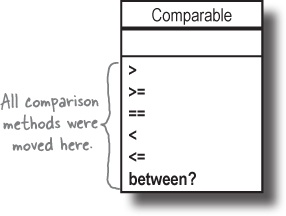

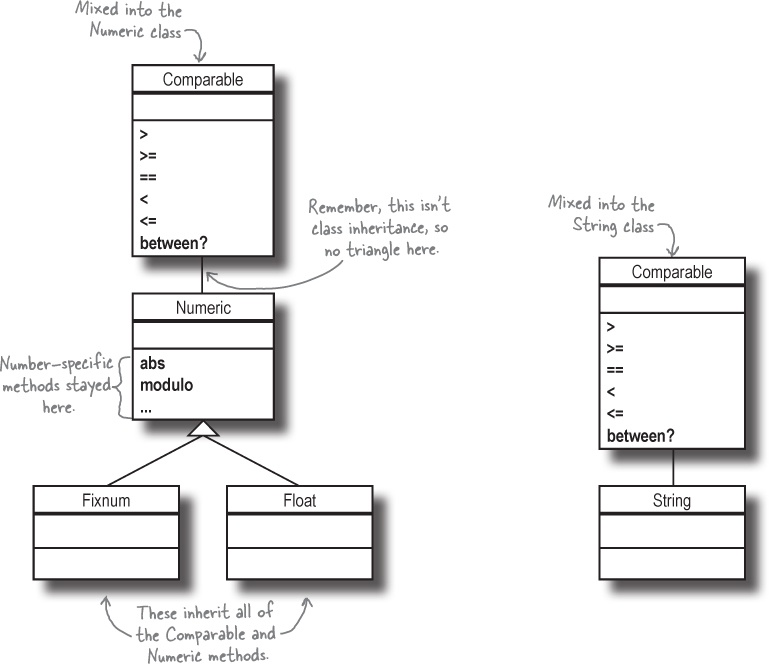

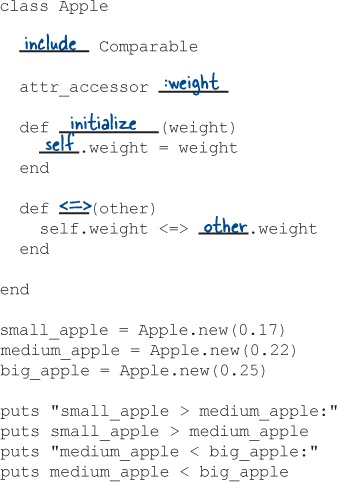

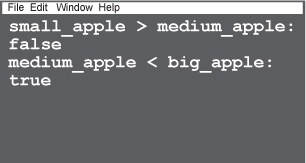

Because so many different kinds of classes need the <, < =, ==, >, and >= methods, it wasn’t practical to use inheritance. Instead, Ruby’s creators put these five methods (plus a sixth, between?, which we’ll talk about later) into a module named Comparable.

Then, they mixed the Comparable module into Numeric, String, and any other class that needed comparison operators. And just like that, those classes gained <, < =, ==, >, >=, and between? methods!

Mixing the Comparable module into a class lets you use comparison operators with that class.

And here’s the really great part: you can mix Comparable into your classes, too! Hmm...but what class shall we use it for?

Choice (of) beef

We’d like to take a moment to talk to you about a topic near and dear to our hearts: steak. In the USA, there are three “grades” of beef, which describe its quality. In order, from best to worst, they are:

Prime

Choice

Select

So a “Prime” steak is going to give you a more delicious dining experience than a “Choice” steak, and “Choice” will be better than “Select.”

Suppose we have a simple Steak class, with a grade attribute that can be set to either "Prime", "Choice", or "Select":

class Steak attr_accessor :grade end

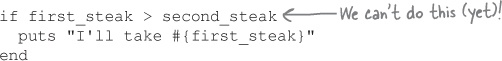

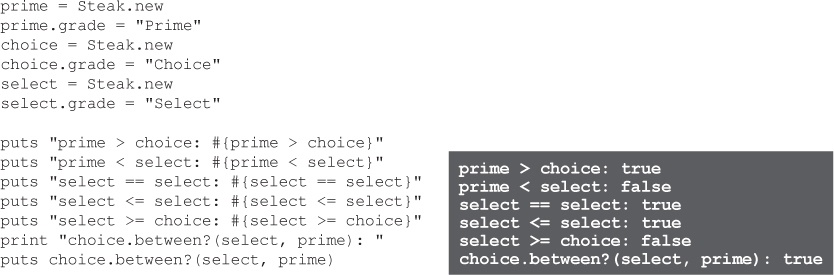

We want to be able to easily compare Steak objects, so that we know which to buy. In other words, we want to be able to write code like this:

As we learned back in Chapter 4, comparison operators like > are actually calls to an instance method on the object being compared. So if you see code like this:

4 > 3

...it actually gets converted to a call to an instance method named > on the 4 object, with 3 as its argument, like this:

4.>(3)

So what we need is an instance method on our Steak class, named >, that accepts a second Steak instance to compare to.

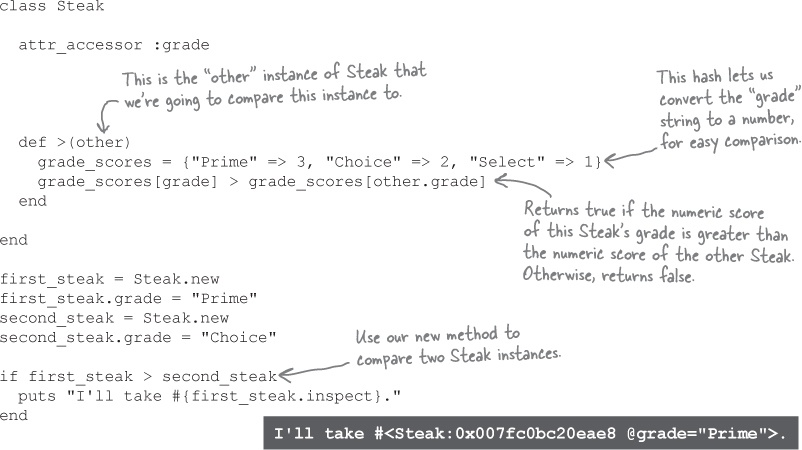

Implementing a greater-than method on the Steak class

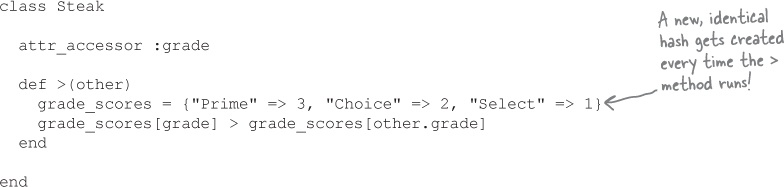

Here’s our first attempt at a > method for our Steak class. It will compare the current object, self, to a second object and return true if self is “greater,” or false if the other object is “greater.” We’ll compare the grade attribute of the two objects to determine which is greater.

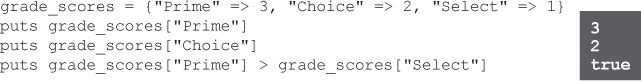

The key to our new > method is the grade_scores hash, which lets us look up a grade ("Prime", "Choice", or "Select") and get a numeric score instead. Then, all we have to do is compare the scores!

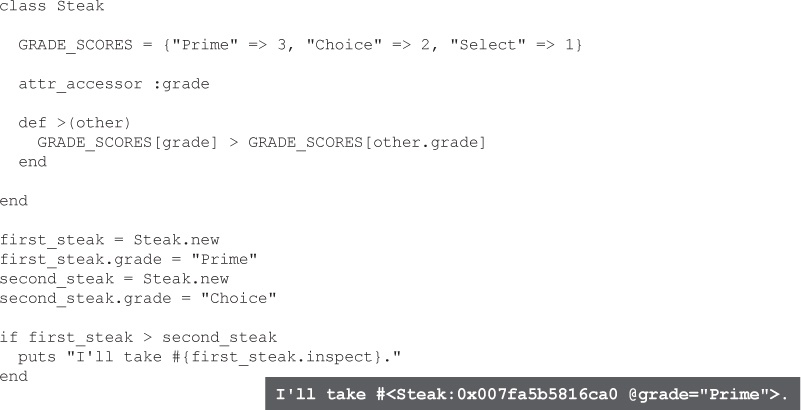

With the > method in place, we’re able to use the > operator in our code to compare Steak instances. A Steak with an assigned grade of "Prime" will be “greater” than a Steak with a grade of "Choice", and a Steak with a grade of "Choice" will be greater than a Steak with a grade of "Select".

There’s just one problem with this code: it creates a new hash object and assigns it to the grade_scores variable every time the > method runs. That’s pretty inefficient. So, if you’ll bear with us, we need to take a quick detour to talk about constants...

Constants

The > method on our Steak class creates a new hash object and assigns it to the grade_scores variable every time it runs. That’s pretty inefficient, considering the contents of the hash never change.

For situations like this, Ruby offers the constant: a reference to an object that never changes.

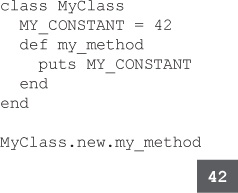

If you assign a value to a name that begins with a capital letter, Ruby will treat it as a constant rather than a variable. By convention, constant names should be ALL_CAPS. You can assign a value to a constant within a class or module body, and then access that constant from anywhere within that class or module.

Conventional Wisdom

Use ALL CAPS for constant names. Separate words with underscores.

PHI = 1.618 SPEED_OF_LIGHT = 299792458

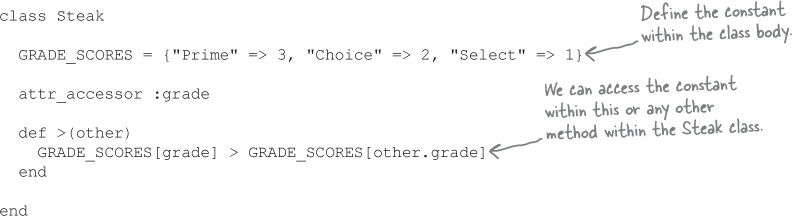

Instead of redefining our hash of numeric equivalents for beef grades every time we call the > method, let’s define it as a constant. Then, we can simply access the constant within the > method.

Our code will work the same using a constant as it did using a variable, but we only have to create the hash once. This should be much more efficient!

We have a lot more methods to define...

Our revised > method for comparing Steak methods is working great...

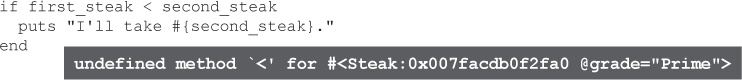

But that’s all we have: the > operator. If we try to use <, for example, our code will fail:

The same goes for < = and >=. Object has an == method that Steak inherits, so the == operator won’t raise an error, but that version of == doesn’t work for our needs (it only returns true if you’re comparing two references to the exact same object).

We’ll need to implement methods for all of these methods before we can use them. Doesn’t sound like a fun task, does it? Well, there’s a better solution. It’s time to break out the Comparable module!

The Comparable mixin

Ruby’s built-in Comparable module allows you to compare instances of your class. Comparable provides methods that allow you to use the <, < =, ==, >, and >= operators (as well as a between? method you can call to determine if one instance of a class is ranked “between” two other instances).

Comparable is mixed into Ruby’s string and numeric classes (among others) to implement all of the above operators, and you can use it, too! All you have to do is add a specific method to your class that Comparable relies on, then mix in the module, and you gain all these methods “for free”!

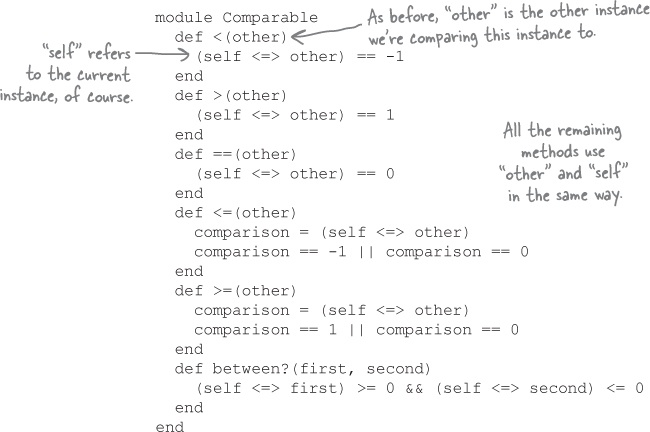

If we were to write our own version of Comparable, it might look like this:

The spaceship operator

That’s the “spaceship operator.” It’s a kind of comparison operator.

Many Rubyists call < => the “spaceship operator,” because it looks like a spaceship.

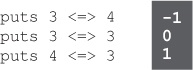

You can think of < => as a combination of the <, ==, and > operators. It returns -1 if the expression on the left is less than the expression on the right, 0 if the expressions are equal, and 1 if the expression on the left is greater than the expression on the right.

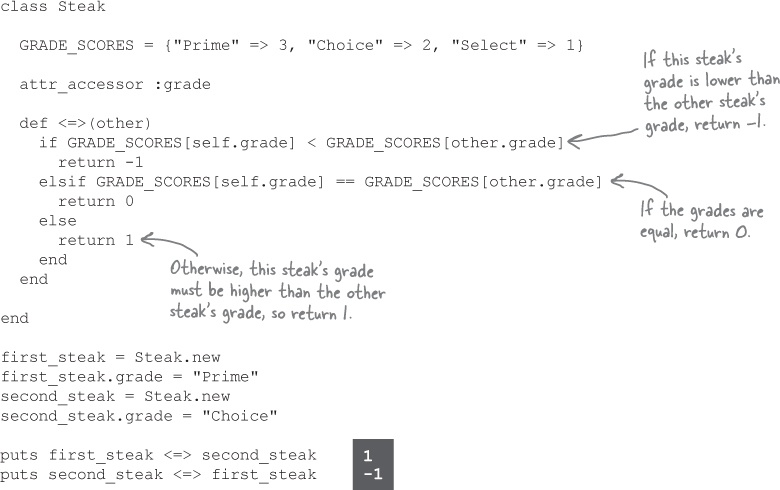

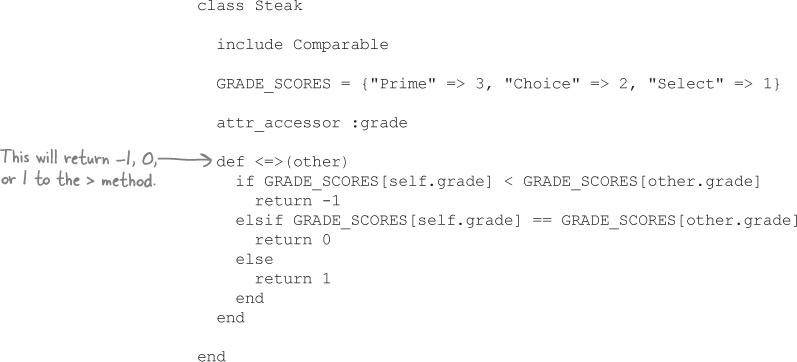

Implementing the spaceship operator on Steak

We mentioned that Comparable relies on a specific method being in your class... That’s the spaceship operator method.

Just like <, >, ==, and so on, < => is actually a method behind the scenes. When Ruby encounters something like this in your code:

3 < => 4

...it converts it to an instance method call, like this:

3. < =>(4)

Here’s what that means: if we add a < => instance method to the Steak class, then whenever we use the < => operator to compare some Steak instances, our method will be called! Let’s try it now.

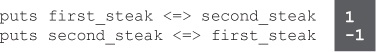

If the steak to the left of the < => operator is “greater” than the steak to the right, we’ll get a result of 1. If they’re equal, we’ll get a result of 0. And if the steak on the left is “lesser” than the steak on the right, we’ll get a result of -1.

Of course, code that used < => everywhere wouldn’t be very readable. Now that we can use < => on Steak instances, we’re ready to mix the Comparable module into the Steak class, and get the <, >, < =, >=, ==, and between? methods working!

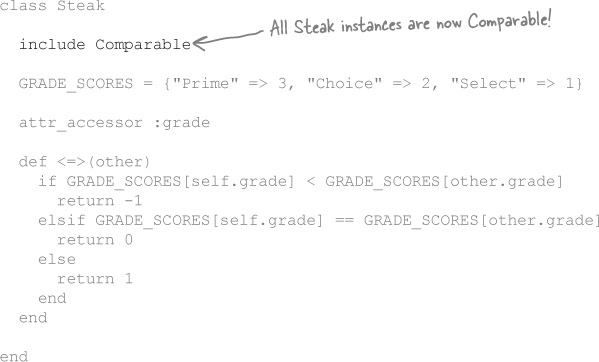

Mixing Comparable into Steak

We’ve got the spaceship operator working on our Steak class:

...which is all the Comparable mixin needs in order to work with Steak. Let’s try mixing in Comparable. We just have to add one more line of code to do so:

With Comparable mixed in, all the comparison operators (and the between? method) should instantly begin working for Steak instances:

How the Comparable methods work

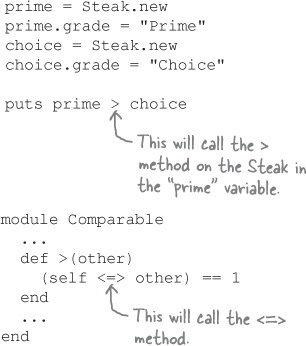

When a > comparison operator appears in your code, the > method is called on the object to the left of the > operator, with the object to the right of the > as the other argument.

This works because Comparable has been mixed in to your class, so the > method is now available as an instance method on all Steak instances.

The > method, in turn, calls the < => instance method (defined directly within the Steak class) to determine which Steak’s grade is “greater.” The > method returns true or false according to the return value of < =>.

And we wind up selecting the tastiest steak!

The <, < =, ==, >=, and between? methods work similarly, relying on the < => method to determine whether to return true or false. Implement the < => method and mix in Comparable, and you get the <, < =, ==, >, >=, and between? methods for free! Not bad, eh? Well, if you like that, you’re going to love the Enumerable module...

Our next mixin

Remember that awesome find_all method from Chapter 6? The one that let us easily select elements from an array based on whatever criteria we wanted?

Note

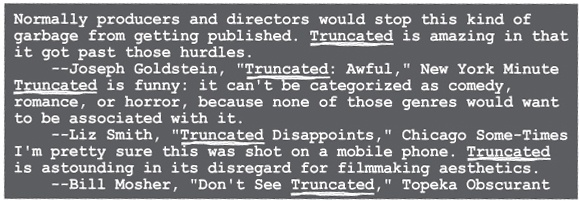

relevant_lines = lines.find_all { |line| line.include?("Truncated") }This shortened code works just as well: only lines that include the substring "Truncated" are copied to the new array!

puts relevant_lines

Remember the super-useful reject and map methods from the same chapter? All of those methods come from the same place, and it isn’t the Array class...

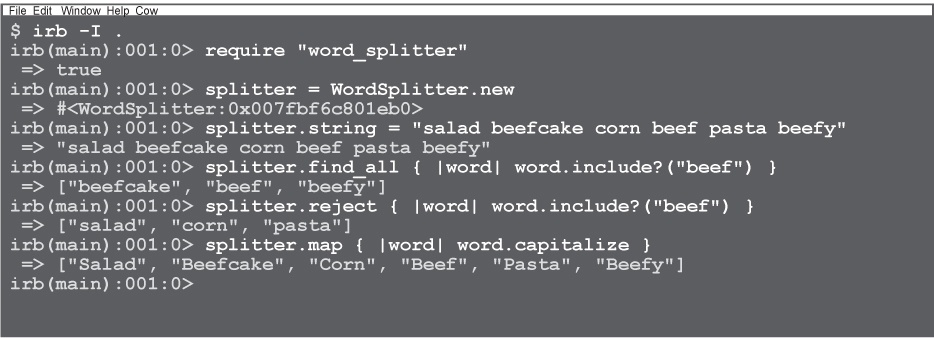

The Enumerable module

Just as Ruby’s string and numeric classes mix in Comparable to implement their comparison methods, many of Ruby’s collection classes (like Array and Hash) mix in the Enumerable module to implement their methods that work with collections. This includes the find_all, reject, and map methods we used back in Chapter 6, as well as 47 others:

Mixing the

Enumerablemodule into a class adds methods for working with collections.

Instance methods from Enumerable:

all? find_all none? any? find_index one? chunk first partition collect flat_map reduce collect_concat grep reject count group_by reverse_each cycle include? select detect inject slice_before drop lazy sort drop_while map sort_by each_cons max take each_entry max_by take_while each_slice member? to_a each_with_index min to_h each_with_object min_by to_set entries minmax zip find minmax_by

And just like Comparable, you can mix in Enumerable to get all of these methods on your own class! You just have to provide a specific method that Enumerable needs to call. It’s a method you’ve worked with before on other classes: the each method. The methods in Enumerable will call on your each method to loop through the items in your class, and perform whatever operation you need on them.

Comparable:

Provides

<,>,==, and three other methodsIs mixed in by

String,Fixnum, and other numeric classesRelies on host class to provide

< =>method

Enumerable:

Provides

find_all,reject,mapand 47 other methodsIs mixed in by

Array,Hash, and other collection classesRelies on host class to provide

eachmethod

We don’t have nearly enough space in this book to cover all the methods in Enumerable, but we’ll try out a few in the next few pages. And in the upcoming chapter on Ruby documentation, we’ll show you where you can read up on the rest of them!

A class to mix Enumerable into

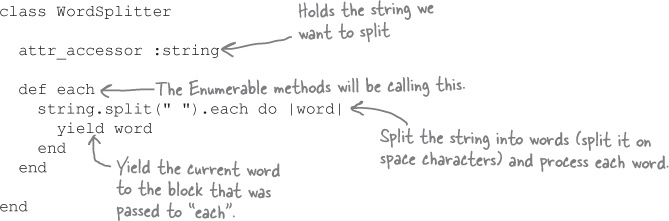

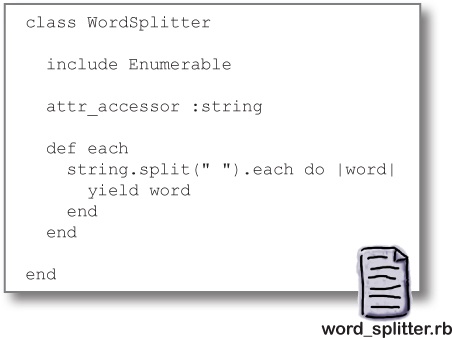

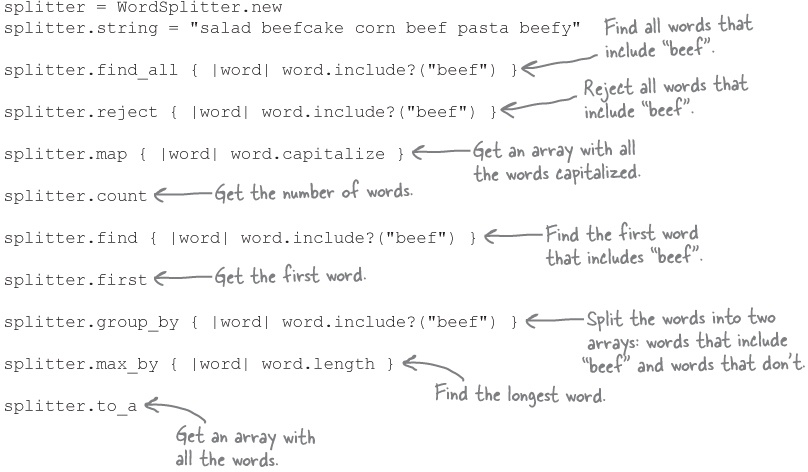

To test out the Enumerable module, we’re going to need a class to mix it into. And not just any class will do...we need one with an each method.

That’s why we’ve created WordSplitter, a class that can process each word in a string. Its each method splits the string on space characters to get the individual words, then yields each word to a block. The code is short and sweet:

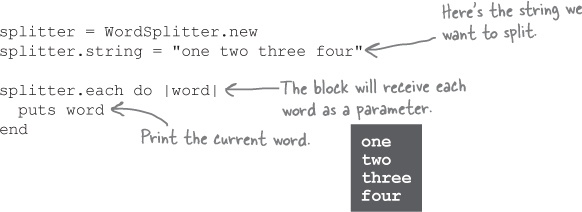

We can test that the each method works by creating a new WordSplitter, assigning it a string, and then calling each with a block that prints each word:

That one each method is cool and all...but we want our 50 Enumerable methods! Well, now that we have each, getting the additional methods is as easy as mixing Enumerable in...

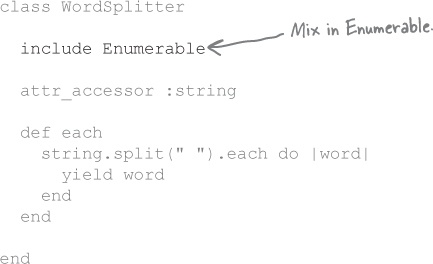

Mixing Enumerable into our class

Without further ado, let’s mix Enumerable into our WordSplitter class:

We’ll create another instance and set its string attribute:

splitter = WordSplitter.new splitter.string = "how do you do"

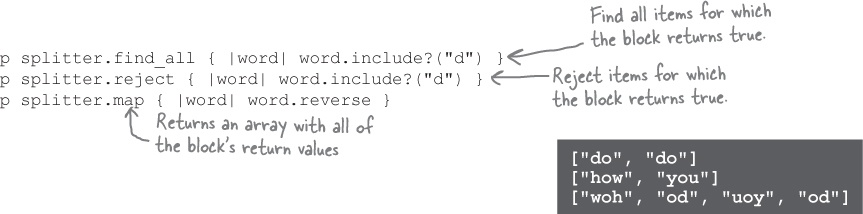

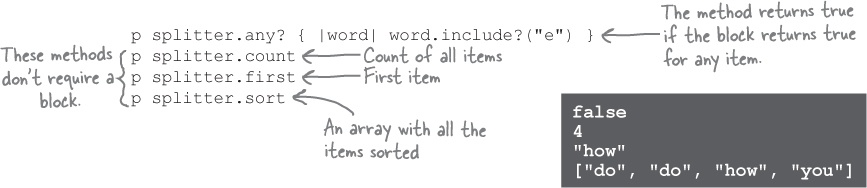

Now, let’s try calling some of those new methods! The find_all, reject, and map methods work just like we saw back in Chapter 6, except that instead of passing array elements to the block, they pass words! (Because that’s what they get from WordSplitter’s each method.)

We get lots of other methods, too:

We get 50 methods in all! That’s a lot of power just for adding one line to our class!

Inside the Enumerable module

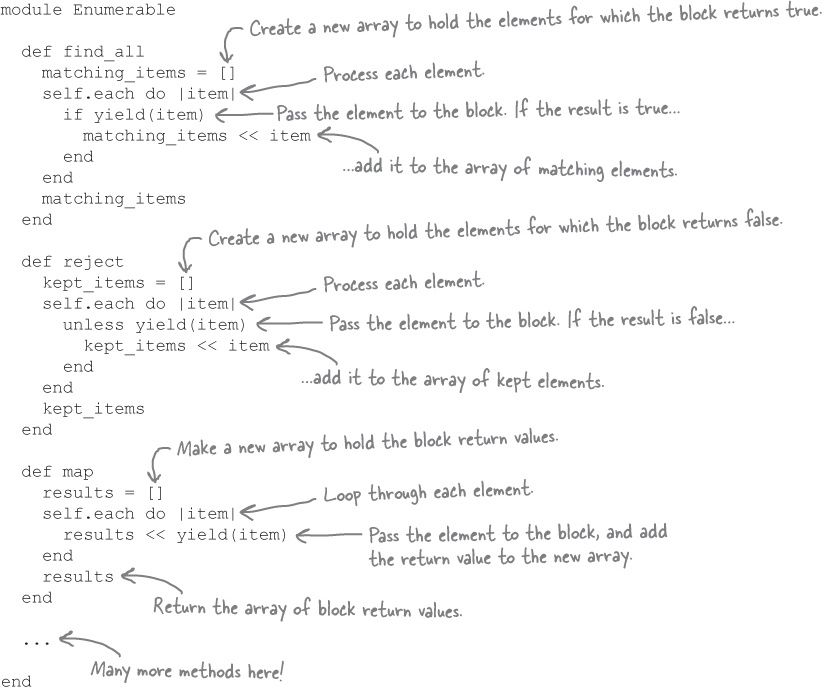

If we were to write our own version of the Enumerable module, every method would include a call to the each method of the host class. Enumerable’s methods rely on each in order to get items to process.

Here’s what the find_all, reject, and map methods might look like:

Our custom Enumerable would have other methods besides find_all, reject, and map, though. Many others. All of them would be related to working with collections. And all of them would include a call to each.

Just as the methods in Comparable rely on the < => method to compare two items, the methods in Enumerable rely on the each method to process each item in a collection. Enumerable doesn’t have its own each method; instead, it relies on the class you’re mixing it into to provide one.

This chapter has given you just a taste of what the Comparable and Enumerable modules can do for you. We encourage you to experiment with other classes. Remember, if you can write a < => method for it, you can mix Comparable into it. And if you can write an each method for it, you can mix Enumerable into it!

Up Next...

In the next chapter, you’ll find out where we learned about all of these cool classes, modules, and methods: Ruby’s documentation. And you’ll learn how to use it yourself !