CHAPTER 2

THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONALISM IN IT AND SERVICE MANAGEMENT

2 The evolution of professionalism in IT and service management

This chapter provides guidance for professionals in IT and service management who are required to build and maintain a broad professional portfolio. The content of this chapter may be familiar, as it relates to organizational structures, people, communications, and the importance of being aware of new opportunities. These particular areas are emphasized in ITIL 4 because they are as important for success as processes, practices, and technical knowledge. To be successful in the provision of IT and digitally enabled products and services, it is important to develop a good understanding of and practical skills in a broad range of guidance.

2.1 Organizations, people, and culture

2.1.1 Organizational structures

Definition: Organization

A person or a group of people that has its own functions with responsibilities, authorities, and relationships to achieve its objectives.

Service relationships require many and varied interactions between individuals and groups both within and between organizations. Individuals and organizational structures:

•interact with information and technology

•participate in value streams and processes

•work with partners and suppliers.

There are many potential organizational structures. An early and crucial decision involves selecting the one that will allow and encourage individuals to create, deliver, and support products and services. Some organizational structures are hierarchical, whereas others more closely resemble a network or matrix. A common approach involves grouping people functionally: by their specialized activities, skills/expertise, and resources, although this can lead to individuals working in isolation with little understanding of what anyone else is doing. In contrast, cross-functional structures (which may share a focus on a product or service) can leave the organization without a comprehensive overview of their portfolio and may result in duplication of effort.

Current organizational thinking favours self-organizing structures that work towards common objectives. Unfortunately, not every team can take an impromptu and Agile approach to self-organization.

Types of organizational structure include:

• Functional These are typically hierarchical arrangements based on organizational control, lines of authority, or technical domain. These arrangements determine how power, roles, and responsibilities are assigned and how work is managed across different levels. The organization may be divided into internal groups based on functional areas, such as HR, IT, finance, marketing, etc.

• Divisional Divisionally based organizations arrange their activities around market, product, or geographical groups. Each division may be responsible for its own accounting, sales and marketing, engineering, production, etc.

• Matrix Reporting relationships are organized as a grid or matrix, with pools of people who can move across teams as needed. Employees in this structure often have dual reporting relationships; for example, both to a line manager and to a product, project, or programme of work.

• Flat Some organizations reduce hierarchical reporting lines because they are seen as barriers that hinder decision-making. As the organization grows, these structures become a challenge to maintain.

The key differences between the various organizational structures can be described using the following characteristics:

•grouping/teaming criteria (function/product/territory/customer, etc.)

•location (co-located/distributed)

•relationships with value streams (responsible for specific activities or fully responsible for the end-to-end value stream)

•team members’ responsibility and authority (command-and-control or self-driven teams)

•sourcing of competencies (level of integration with teams external to the organization).

Historically, organizational structures have been functional and hierarchical in nature, with military-style lines of command and control.

In the digital service economy, agility and resilience are vital for an organization’s success. Organizations must adopt new ways of structuring their resources and competencies. Common approaches include:

•the faster and more flexible allocation of resources to new or more important tasks. Matrix organizational structures are adept at allocating or reallocating resources to different value streams, projects, products, or customers. This is often combined with outsourcing arrangements to ensure an increase of resources and competencies when necessary.

•permanent, simple multi-competent teams that are assigned to work exclusively on a product. This may result in occasions when teams are unoccupied, but it ensures a high availability of teams for the development and management of products.

In order to adapt to more flexible and responsive ways of working, such as Agile and DevOps, many organizations have adjusted their organizational structures. This includes ensuring that a leader’s role is closer to that of a ‘servant’. It also involves creating cross-functional teams, which can be achieved by applying matrix and flat structures.

Organizational structure changes should be managed carefully, as they can cause major cultural challenges within the organization if handled badly. It is useful to refer to the ITIL guiding principles and the organizational change management practice for guidance.

2.1.2 Using the ITIL guiding principles to improve the organizational structure

The ITIL 4 guiding principles are valuable references when planning to improve organizational structures. It is useful to consider the following:

• Focus on value What is the key driver for changing the structure? It is important to ensure that this is reviewed and referenced at each stage of the transformation.

• Start where you are The cultural aspects of the organization should be considered. For instance, what is the relative maturity of the current organizational structures? Value stream mapping and RACI matrices can be used to understand current roles and responsibilities.

• Progress iteratively with feedback The transition/transformation should be simplified into manageable steps to ensure that it is possible to adapt to changing requirements.

• Collaborate and promote visibility It is important to ensure that all stakeholders are engaged throughout the change process. A ‘disagree and commit’ approach, in which every stakeholder discusses their concerns with the rest and is then expected to come to an agreement, can help changes to progress quickly. Leaders should adopt an ‘open-door’ policy to become easily accessible. Organizational changes must be clearly defined and openly discussed to facilitate transparency.

• Think and work holistically Collaborating with all the appropriate leaders/managers will ensure that potential risks are understood and managed. It will also help to communicate a consistent message about the risks and the progress that is being made towards transformation.

• Keep it simple and practical It is important to reduce the complexity of the organization as much as possible so that the flow of work and information is uninhibited. Efficiency and effectiveness can be improved by reducing the transferrals of work. Where possible, teams can be encouraged to be self-organizing by making decisions and taking actions within certain criteria without the need to check with management.

• Optimize and automate Where possible, tasks should be consolidated or automated to reduce waste. Human intervention should only occur when it contributes a defined value.

Key message

Roles and jobs

A role is a set of responsibilities, activities, and authorizations granted to a person or team, in a specific context.

A job is a position within an organization that is assigned to a specific person.

A single person may, as part of their job, fulfil many different roles. A single role may be contributed to by several people.

Traditionally, roles in IT and technology followed specific technical competencies. These roles, which were clearly defined, were within the development and operational areas and included programmers, business analysts, tech support, designers, and integrators. More recently, organizations have been struggling to build career paths for their employees because roles and job requirements are constantly changing.

The new workplace requires greater flexibility and the ability to constantly adapt to new requirements and technologies. In IT and service management, this involves a wider definition of skills, competencies, and areas of work, reflecting the changes in teams and organizational structures. The transformation from hierarchical structures to matrix-managed cross-functional teams has expanded the definition of roles. As a result, individuals are now expected to transfer more readily between roles.

In addition, there is now an expectation that professionals in IT and service management will possess a wider range of business competencies, supported by demonstrable skills, experience, and qualifications. Many of these are transferable business skills that have been obtained from other areas of work and used successfully by IT professionals for years. However, they have only recently been recognized as being of equal importance to technical skills and qualifications.

As the technology industry moves closer to becoming a mainstream business function, generic business and management competencies will increasingly become compulsory requirements for IT and technology roles.

2.2.2 Professional IT and service management skills and competencies

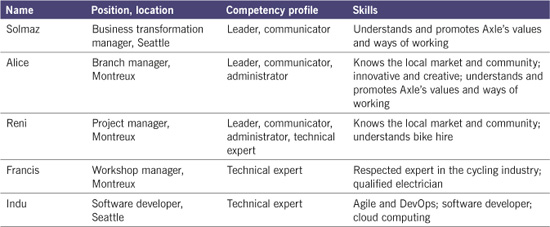

The structuring and naming of roles differs between organizations. The roles defined in ITIL are not compulsory; organizations should utilize and adapt them to suit their specific needs. The ITIL practice guides describe each role using a competency profile based on the model shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Competency codes and profiles

Competency code |

Competency profile (activities and skills) |

L |

Leader Decision-making, delegating, overseeing other activities, providing incentives and motivation, and evaluating outcomes |

A |

Administrator Assigning and prioritizing tasks, record-keeping, ongoing reporting, and initiating basic improvements |

C |

Coordinator/communicator Coordinating multiple parties, maintaining communication between stakeholders, and running awareness campaigns |

M |

Methods and techniques expert Designing and implementing work techniques, documenting procedures, consulting on processes, work analysis, and continual improvement |

T |

Technical expert Providing technical (IT) expertise and conducting expertise-based assignments |

Successfully performing an activity requires a combination of competencies, each of which will vary in importance depending on the activity. The position of the competency in a competency code illustrates its relative importance. For example:

•In the CAT competency profile, communication and coordination skills are very important, administrative skills are somewhat important, and technical knowledge is useful but less important for the described activity. This combination is relevant, for example, for a relationship manager and a service owner drafting a new or amended service level agreement (see the service level management practice guide, section 4.1, for details).

•In the TMA competency profile, technical knowledge is very important, method design skills are somewhat important, and administrative skills are useful but less important for the described activity. This combination is relevant, for example, for a change manager and a service owner initiating an improvement of a change model (see the change enablement practice guide, section 4.1, for details).

Understanding a role’s competency profile helps to:

•identify the best candidates (or groups) to perform the role

•identify gaps and plan the professional development of team members

•define requirements to newcomers and create job and role descriptions

•align the organization’s workforce and talent management practice with industry competency models and professional development programmes.

Only a few activities and roles demand technical skills and knowledge. For the majority of competency profiles, communication or administrative competencies are the most important. Once the high-level profile is understood, industry competency models, such as the European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) or the Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA) can be used to detail the requirements and to plan professional development.

Some examples of the skills and knowledge needed in service management are:

• Communication The ability to establish good working relationships with a variety of stakeholders at several levels using a variety of communication techniques. This includes verbal and written communication, the use of various types of media, and the adoption of appropriate language and tone. Good communication is a vital skill which encourages positive interactions with colleagues, customers, managers, staff, and other stakeholders.

• Business and commercial Most technology environments use a mixture of supplier and commercial relationships. Service managers utilize their commercial skills to specify, buy, negotiate, and manage such relationships. Procurement and contract management skills, in particular, are in high demand. Budgeting and financial management are also key service management requirements, as is the ability to write and sell a business case. There is also a need to produce promotional materials to advertise the service, either in an internal or external capacity.

• Relationship management Developing as a key skill set, this involves acting as a point of contact and liaison, capturing demand, and demonstrating value between business, customer, and supplier groups. Service managers may also function as the active liaison and synchronizer of information, feedback, demand, and progress between parties. Additionally, relationship managers convey requirements and feedback to the relevant groups to ensure a smooth flow of information and actions between groups.

• Leadership Beyond team or line management, leadership involves the ability to influence, motivate, and support individuals in their work. Leadership does not simply come from managers. Great leaders are those individuals who show initiative, take ownership, and empathize with and inspire others to get things done. When building teams, it is important to include individuals who possess these skills to act as leaders and create a great working culture.

• Market and organizational knowledge As a result of the reduction in distinction between IT and business roles and teams, those in technology roles have a greater need to understand the business and market sector of their organization. For example, such individuals should be aware of the developments in the market regarding competitors, relative costs, and opportunities.

• Management and administration Successful service management also requires good people management, delegation, documentation, and logistical skills. Much of the work involves bringing people together, agreeing on actions, and providing useful and practical documentation. Good managers are invaluable when building successful teams as they can hire the appropriate people and manage and develop their employees’ careers.

• Developing innovation A business and entrepreneurial mindset is becoming more of a requirement, even within internal service management organizations. This is required to identify new ways of working, delivering services, and solving problems. It may involve exploiting new technologies, creative and innovative thinking, or customer interactions.

2.2.2.1 Generalist or ‘T-shaped’ models

In the past, individuals were typically viewed as either generalists or specialists. Today, this viewpoint does not reflect the outcomes that organizations expect and need. Organizations are looking for people to be T-shaped, pi-shaped (π), or comb-shaped (Ш), as outlined below:

•A T-shaped individual is an expert in one area who is also knowledgeable in other areas. For example, a developer or tester who possesses knowledge of accounting.

•A pi-shaped individual is an expert or near-expert in two areas and knowledgeable in other areas. For example, someone who can both design and develop but also possesses good testing skills.

•A comb-shaped individual is strong in more than two areas and knowledgeable in other areas. For example, someone who can gather requirements, design, and develop and who has a good knowledge of the adjacent areas.

In the past, pi-shaped individuals were usually senior staff who had developed their skills over time by working in different domains. However, this has changed: new hires may be skilled in multiple areas but not be specialized in any. Many individuals take a proactive approach to developing their skills and knowledge. T-shaped individuals tend to be inquisitive; they like to learn new skills and will acquire them whenever opportunity allows.

Although a clear focus on one competency creates deeper understanding, it can be dangerous to have only one area of expertise. This is because, in the rapidly evolving technology industry, an individual may find that their area of expertise is no longer relevant.

2.2.2.2 Developing a broad set of competencies

There is no single path to achieving proficiency in the competencies required for service management. Many training and certification programmes are available, for instance in technical products and for specific skills like business analysis, programming, and risk management.

Other ways of gaining and recognizing a wider set of competencies as part of service management include:

• building job descriptions that clarify each of the non-technical requirements for the role

• developing recruitment and onboarding skills

• recognizing non-IT experience in job applications; for example, team management, procurement, and contract management

• ensuring that skills matrices include appropriate soft skills, such as communications, leadership, and innovation

• reflecting and rewarding the full scope of required competencies in staff performance management, appraisals, and reward programmes

• ensuring that all staff and management are given opportunities for training and development outside traditional technical and process management, such as for management, leadership, team building, negotiation, report writing, business case preparation, relationship management, presenting, business administration, budgeting, marketing, and selling

• encouraging continuing professional development (CPD) programmes that recognize and develop all of the above at a practical level

• encouraging employees to investigate new ideas, tools, ways of working, etc.; for example, many organizations provide CPD points for attending events relating to their industry, workshops, conferences, etc. Individuals should be encouraged to develop their skills in broad and diverse ways

• managing role-based and competency-based models and schemes to develop and recognize training, experience, qualifications, and testimonials that help to provide evidence of an individual’s competency levels

• role-based models have clearly defined job descriptions with integrated career progression paths; they are useful in the development of job-related career paths and in building the appropriate skills, but there can be challenges in maintaining these when roles and skills change regularly

• competency-based models are focused on generic competencies and are useful when developing a holistic approach to skill acquisition; these can also be useful in supporting talent management, although it can be difficult to map to exact roles

• hybrid role-based and competency-based models combine the job-related and talent-related aspects of the models.

2.2.3 Workforce planning and management

In today’s talent-based economy, the workforce itself is arguably the most important tangible asset of most organizations. Despite its importance, this asset is often not carefully planned, measured or optimized.

Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM).

Key message

The purpose of the workforce and talent management practice is to ensure that the organization has the right people with the appropriate skills and knowledge and in the correct roles to support its business objectives. The practice covers a broad set of activities focused on successfully engaging with the organization’s employees and people resources, including planning, recruitment, onboarding, learning and development, performance measurement, and succession planning.

A good workforce planning strategy should identify the roles, together with the knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes associated with them, that keep an organization functioning. It should also address the emerging technologies, leadership, and organizational changes required to progress the organization’s growth and success.

Fundamentally, workforce and talent management is a set of specific approaches for recruiting, retaining, developing, and managing employees. Workforce planning involves understanding how employees can be used to meet an organization’s business goals. This can include determining how many employee hours are needed for a project and identifying the skills the employees will need to ensure that the organization meets its goals and continues to improve its performance.

Workforce planning is a competency that is highly desired by managers. However, the impact of current and future vacancies on the organization’s ability to execute its strategy often goes unrecognized, and there is also a tendency to allocate insufficient time to its implementation.

2.2.3.1 Capacity planning

Successful service delivery requires an understanding of the competencies needed and the amount of each resource required. In many organizations, the project management office is responsible for identifying and scheduling the resources needed for development, testing, release, and deployment. The support, training, and user resources needed for deploying and maintaining services is, however, often missing.

There must be enough time allocated for resolving incidents, requests, and problems, as well as for building and testing changes and their subsequent release/deployment. The service level targets for the time taken to resolve an issue should be organizational targets, not service desk targets. Accurate forecasts can be developed for incoming incident, request, and problem volumes. Regardless of whether it is applications, infrastructure, service desk, desktop support, or any other team (including service consumers), the challenge is ensuring that enough people with the required skills, abilities, and competencies are available to complete all the different stages from design through to support of services.

The workforce and talent management practice requires a service value network with service value chains and clearly defined inputs, outputs, and outcomes. The workforce must also be motivated and engaged in order to achieve high customer value. Management is responsible for ensuring that staff are trained, engaged, and valued so that they are more likely to remain with the organization.

Consequently, the increasing use of automation will require a realistic understanding of the resources required for the successful delivery of services. In the past, individuals could be either generalists or specialists. However, as methodologies like Agile and DevOps become more prevalent, roles are becoming increasingly blurred. Regardless of an organization’s size, a variety of competencies are needed to fulfil different roles according to the prevailing circumstances. As a result, new operating models are needed for the successful development, testing, deployment and release, operations, and support of services.

For example, employees may fulfil a variety of distinct roles for individual releases and deployments, and developers and operations staff may take a more active role in resolving incidents. Realistic and achievable schedules will require better forecasting and an understanding of the competencies available to achieve the organization’s goals.

2.2.4 Employee satisfaction management

The true potential of an organization can only be realized when the productivity of individuals and teams are aligned, and their activities are integrated to achieve the goals of the organization. Employees’ morale and engagement can influence their productivity and retention, as well as customer satisfaction and loyalty (happy and satisfied staff are needed for happy and satisfied customers). Organizations should therefore keep employee satisfaction under frequent review in order to understand how well they are meeting the changing needs and expectations of their staff. Employee satisfaction surveys can measure many attributes, including leadership, culture, morale, organizational climate, organizational structure, and job activities.

It is sometimes useful to manage surveys via a third party to maintain confidentiality. Employee satisfaction surveys should be used to baseline their current satisfaction levels and to identify actions that will increase their commitment and trust; these directly impact on the ability of an organization to achieve its goals. Although surveys are a common means of collecting and managing employee feedback, other methods are available, such as casual meetings, regular one-to-one meetings and appraisals, reviewing sickness and attrition levels, staff morale metrics, and other informal communications.

The key elements in collecting employee feedback are:

• Confidentiality Employees should feel able to speak their minds without fear of negative consequences.

• Support and understanding Honest feedback will only be given when employees trust their managers to respond reasonably. Employees should feel that their opinions will be listened to and taken seriously.

• Call to action Employees need to know that their comments will be acted upon. It is important to initiate activities, e.g. to explain a decision that an employee does not support. Employees may not be forthcoming in the future if their opinions were ignored the last time they gave feedback.

2.2.4.1 Feedback types

Employee surveys can be run locally or at an organizational level. The information may be obtained in a variety of ways, from formal annual surveys to more informal and irregular feedback discussions.

Regular one-to-one meetings are a good source of feedback, depending on the relationship between parties; they can also provide more detail than surveys. As an alternative, unstructured meetings, which may include conversations in less-formal settings (for example, in a coffee shop, corridor, or during a journey) can often be the best way to secure honest information.

It is important to review sickness and attrition, as high levels of sickness or staff movement can indicate poor morale. Increasing rates of absence and staff turnover can indicate issues within the organization’s overall culture.

Staff-driven metrics are where an organization allows its teams to submit their own morale indicators. This involves team members discussing and agreeing on a score that reflects their overall morale. These metrics are useful as they provide a system for measuring a team’s overall opinion, although this can be challenging in teams with strong or influential individuals.

Tips

Collecting feedback

It is important to be timely when presenting the results and actions that arise from a survey.

The top four motivation factors for people at work are achievement, recognition, responsibility, and interesting work. They should be accounted for when preparing actions for increasing employee satisfaction.

• Take the personal and emotional out of criticism by discussing the facts of outcomes rather than offering opinions of a person or their skills.

• Use a mixture of open (opinions, emotions, attitudes) questions and closed (data, stats, facts) questions.

• Regularly conduct and improve surveys. They should not be a big event that individuals dread.

Giving feedback

• Do not tell others what you think of their skills. Instead, describe your experience of their work.

• Use specific examples as part of a bigger story.

• Be constructive, holistic, and positive. This will result in a more practical response compared to negative feedback.

• Only provide feedback; do not try to resolve problems.

2.2.5 Results-based measuring and reporting

Continual improvement relies on reporting data together with outputs from various sources to identify whether an objective has been achieved or will or will not be achieved. Organizations similarly use measuring and reporting to drive improvement activities and then track progress against the stated objectives. Business decisions are often made with insufficient or irrelevant data. The availability of reliable metrics should support good business decision-making, because they can clarify facts and experience to drive positive change.

It is important to set appropriate objectives and related metrics, as metrics drive behaviour. Incorrectly calibrated metrics can lead to inappropriate behaviour in order to meet targets. The targets may also be inappropriate for the overall business or customer experience.

It is also essential to develop good metrics that relate to the overall business; the difference between outputs and outcomes must be clear.

2.2.5.1 Results-based approach

A results-based approach focuses only on the outcomes of employee actions; for example, customer experience, successful releases/deployments, sales per month, or the time taken to resolve an issue. This type of approach tends to be viewed as a fair and objective method of measurement. It is most appropriate when individuals have the skills and abilities needed to complete their work and can recognize and correct their behaviour.

The results-based approach is also effective for improving employees’ performance. It motivates individuals to improve their skills and competencies in order to achieve the desired results. It also works when there is more than one way to achieve the desired outcomes, which is often true in IT. This approach encourages individuals to use the appropriate methodology to achieve the desired outcomes for their customers. In addition, it provides greater autonomy for employees to use their information and resources.

According to Fredrick Herzburg,1 achievement, responsibility, interesting work, and recognition are the four top motivational factors for people at work. Organizations can leverage this to increase employee satisfaction and engagement, which benefits not only the employees but also the customers and the organization as a whole.

Organizations will often integrate multiple factors into their performance management systems. For example, a results-based approach may be more applicable to regional retail managers, who focus on setting and achieving quarterly sales goals, than for baristas, who focus on making drinks and engaging with customers.

When setting and measuring individual performance goals, it is important to:

• arrange a face-to-face meeting and agree on a set of individual goals

• ensure that the goals are measurable and documented, which will make it easier for the individual to track their progress

• express the goals in specific terms

• adapt the goals to the individual

• adjust any goals that prove to be unrealistic.

When measuring an employee’s performance, it is important to:

• ensure that the individual’s goals are aligned with those of the team and the organization

• measure both team and individual performances

• include both qualitative and quantitative measures

• allow measures to evolve to ensure that there can be changes in behaviour that drive continual improvement.

Good performance measurements and assessments allow management to initiate improvements and monitor their progress.

The ITIL story: Building effective teams

|

Radhika: We are building a new team to implement Axle’s bike hire pilot. The team needs to have diverse skills, including design thinking, organizational change management, and statistical analysis. Staff members from IT, marketing, the project management office, and other teams are already collaborating on the initial stages of the pilot. |

|

Solmaz: High-performing teams with the right combination of skills and competencies can go a long way in the changing landscape of service management. It is not just about individual expertise any more. Companies can no longer afford to work in silos, or isolate technical and process skills from each other. We need people who can collaborate to improve value streams. |

|

Henri: ITIL 4 is about more than just technology: this is only one enabler in the co-creation of value. Service providers also need to understand customers’ motivations, and their environmental, economic, and political influences. All of this can impact a consumer choice to use, or not use, a service. That is why we bring together diverse skill sets that can identify and design services. |

|

Solmaz: Bike hire is a new service offering for Axle Car Hire. We will leverage existing capability from our car hire business, such as our skills, processes, and IT systems. This honours one of the fundamental ITIL guiding principles; that of ‘start where you are’. The new team for the pilot will be developed iteratively and collaboratively. This will help to ensure that, collectively, the team has all the required competencies. I am the sponsor for the pilot, so I have listed my competencies and skills first in the team’s structure. Next, we need a team member to report back on the pilot. Alice is the branch manager of Axle Car Hire in Montreux and a good fit for this task. |

|

Alice: I encourage a culture of innovation and continual improvement, so my team and I are happy to be involved. |

|

Solmaz: We have a skills gap in project management. We have identified a project manager called Reni with the right skills and availability to manage the pilot. |

|

Reni: I believe in a results-based approach. For me, success is delivering the outcomes of the pilot. Success metrics will be based on timeframe, budget, quality, and customer satisfaction ratings. |

|

Solmaz: Our team also needs someone who has an in-depth knowledge of the cycling industry and the skills to maintain and repair our bikes. Francis is the workshop manager and a former professional cyclist; he is based in Montreux and would be ideal for the role. |

|

Francis: I will be responsible for sourcing, procuring, preparing, and maintaining our bikes. I am also a qualified electrician; this skill allows me to perform maintenance on the electric bikes within our fleet. We want our customers to have a safe, reliable, and enjoyable experience on their cycling journey. |

|

Reni: We will leverage Axle’s car booking system for our pilot; however, updates to the application will be required to include bikes in our service offering. Therefore we need a software developer experienced in Axle’s car booking system. |

|

Indu: I’m a software developer based in the Axle head office. I will provide advice to the Montreux pilot team on the new requirements and also advise of potential impacts to our existing service. |

|

Reni: Our team will work from two locations: Montreux and the Seattle head office. Much of our collaboration will require video-conferencing for meetings and chat apps for quick, regular check-ins. Using both formal and informal communication channels like this will make the team’s work more efficient and effective. |

|

Henri: Collaboration is an important part of Axle’s culture, which promotes self-managing teams. Our pilot team will partner with local suppliers who will help shape our understanding of the bikes and components we need for a successful pilot. |

Bike hire pilot: team structure

Culture can be described as a set of values that are shared by a group of people, including their ideas, beliefs, and practices, as well as their expectations with regard to how individuals within the group should behave. Every organization and social system has a culture. Culture makes human actions predictable, so an understanding of it is a useful management tool.

Culture is a critical factor in the creation, delivery, and support of products and services. Moreover, it provides distinguishing features to service organizations and promotes its value proposition. Service provider organizations focusing on value creation will display these common characteristics:

• a focus on value, quality, and operational excellence

• client, customer, and consumer orientation

• investment in people and communication/collaboration tools

• strong team composition within a structured organization

• continual alignment with the vision, mission, and strategic objectives.

These, or similar, characteristics are expected to be shared by every member and team within the organization. However, specific cultures may be developed at the team level which support the values and principles of the organization but reflect the realities specific to the team. Culture is a difficult concept to grasp because it is generally unspoken and unwritten. It nevertheless influences the dynamics between individuals.

There are widely accepted models for describing cultures and managing cultural differences. For example, culture can be characterized by such characteristics as:

• communication (low context or high context)

• evaluation (direct or indirect negative feedback)

• persuasion (principles versus application)

• leadership (egalitarian or hierarchical)

• decisions (top-down or consensual)

• trust (task-based or relationship-based)

• disagreement (avoidance or escalation of confrontation)

• scheduling (linear or flexible timing).

In a successful organizational culture, teams understand both how they work and where their work fits within the context of the organization’s mission, goals, principles, vision, and values. Team members define their team’s rules and principles within the company’s overall culture. Teams must ensure that they have the information needed to successfully perform their roles in support of any agreed strategy.

Team members should understand that a high percentage of the problems they face as a team will relate to how they interact and relate to each other. The team’s challenge, as individuals and as a team, is to remove the barriers to success.

2.3.2 What does cultural fit mean and why is it important?

Definition: Cultural fit

The ability of an employee or a team to work comfortably in an environment that corresponds with their own beliefs, values, and needs.

An employee who is deemed a good cultural fit is more likely to enjoy their work and their workplace, be happier, commit long term, and be more productive and engaged. A good cultural fit benefits both the team member and the team.

A diverse approach supports good culture as it allows the team or organization to see their work from a broader perspective. Each person brings their unique combination of experience, perspective, skills, and knowledge to the team. The team is greater than the sum of its individual parts.

When hiring for cultural fit, it is important to be aware of bias. It is human nature to gravitate towards like-minded individuals with a similar personality or beliefs. However, this produces homogenous teams and a culture that is less likely to grow or bring the advantage of a variety of perspectives.

2.3.3 How to develop and nurture good team culture

It is possible to grow and evolve a team’s culture over time. First, this requires identifying the team’s current culture and deciding what the desired future outcome is. Change requires ownership and action as a united team. This is a lot easier with good leadership and supportive management. The ITIL guiding principles and the continual improvement model can be very useful tools for implementing change.

The following are simple guidelines for a positive team culture. However, these recommendations should be reviewed and adapted to fit regional, national, and organizational characteristics. Some of the recommendations may be unsuitable for certain organizations.

2.3.3.1 Incorporating vision into the team culture

An important consideration when developing a strong team is to ensure that team members are focused on the collective effort rather than on themselves. A unifying purpose is important when building a strong team. This is aided by encouraging a holistic view of the objectives of the overall organization and of how the work of the team supports it.

The team culture cannot be forced upon individuals. Instead, individuals must be responsible for their own roles within the team culture. The most important task of any leader, therefore, is to clearly communicate the vision and how it will be achieved by the team. Team members need to understand how their contributions fit into the bigger picture, providing them with a sense of purpose and of belonging.

Leaders should continually reinforce the team vision by instilling a sense of purpose to help them develop and increase productivity.

2.3.3.2 Regular meetings

Regular meetings make a big difference to team culture. They build relationships between team members, encourage productivity, and focus on the need for improving team performance.

Meetings should be scheduled in advance and attendees should be acquainted with the agenda beforehand. There must also be clearly defined roles for meetings; for example, one person leads the meeting while another takes notes.

Meetings should focus on the discussion of problems and possible solutions. They need to be efficiently managed, and detailed discussions should be avoided unless necessary.

2.3.3.3 Create leaders

A great team culture prioritizes mentorship over management. Leaders play an important role in forming the culture of the team. Communication must be clear so that each team member has the same understanding of the objectives and issues. Working arrangements should be flexible enough to allow each employee to work in their most effective way but not so flexible that they become difficult to manage.

Team members should be mentored on giving constructive feedback that encourages productivity rather than hindering it by causing embarrassment. Leaders and managers should facilitate and participate in improvement efforts alongside team members. Leadership skills are best learned through example: good leaders give individuals their time and support, remembering that everyone has something to offer.

2.3.3.4 Encouraging informal teams

Informal teams often work more efficiently than formal ones, because issues frequently fall across organizational reporting lines. Informal teams encourage employees to tackle concerns themselves instead of escalating every decision to senior management.

2.3.3.5 Cross-training employees

When employees understand how the various areas of the organization work, they are more likely to make decisions that benefit the organization rather than just their own department or group. It is important to provide employees with opportunities to learn about other roles within the organization. Some organizations go as far as switching employee roles on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis, including managerial roles. Top executives, for example, should spend a few days working on the front lines with customers or directly with the product. Such experiences will provide them with a new appreciation for and understanding of front-line employees.

2.3.3.6 Integrating socially

It is important to take the time to get to know employees personally. People work and support each other better if they understand each other as individuals, helping to identify their strengths, bolster their weaknesses, and develop their latent skills. Great leaders understand how to utilize the talent around them. They learn how to motivate their team to go beyond what is expected of them. This requires an approach that is sympathetic to local culture: it does not need to be intrusive.

2.3.3.7 Providing feedback

Proactive and constructive feedback is one of the best ways to help a team continue to improve. Feedback does not need to be provided in a formal or complicated format. In fact, feedback is often more effective when it is informal and part of an ongoing conversation.

Everyone is different and, consequently, the method for delivering feedback should be customized for each individual. This is another reason why it is important to develop relationships with team members. When an individual trusts another, they are more likely to support their suggestions.

2.3.3.8 Promoting a culture of learning

It is important to promote a culture where each individual is encouraged to continually develop their skills. A culture of learning can be achieved by providing access to regular training and personal development. Online learning has made this even easier, as individuals can learn when it best suits them. Opportunities for team members to take on new responsibilities should be created.

Employees should be encouraged to take up training opportunities. Together with being given sometimes challenging (but achievable) goals, training helps generate feelings of progress that prevent team members from becoming complacent or bored in their positions. The learning of new skills also adds value to the team and workplace. Individuals with access to the tools and methods they need to be successful in their careers will be more engaged, which will create a stronger work environment. A great team culture is great for business.

2.3.4 A continual improvement culture

A culture of continual improvement is important because it improves customer experience, embeds good practice, reduces costs, improves operational efficiency, develops employee experiences, accelerates delivery, removes waste and repetitive tasks, and reduces risk.

The challenge with continual improvement is that it does not happen by itself, or simply because there is a process or workflow defined for it, or because there is an improvement register in place. It needs regular attention. Sometimes an organization may insist that its staff engage in continual improvement but discover that it does not provide valuable or usable content. Careful thought must therefore be invested in identifying individual and organizational needs and then finding learning/training opportunities that are suitably tailored to requirements.

The real benefit of continual improvement comes when the organization has a culture that supports, promotes, and empowers all parties to commit to it in their daily work. Continual improvement should not be thought of as a tool or process to be used occasionally. Instead, it should be embedded in the culture of the organization, and thus promoted, supported, and expounded daily by the management and leadership of the organization. The success of continual improvement initiatives should be celebrated across the organization. Understanding how to build and maintain such a culture requires careful planning and awareness of the current ways of working.

Some organizations have a positive culture, which is noticeable even when entering their offices and meeting their employees. In many cases, this has gradually evolved due to the influence of the approach of key individuals. Often, the culture changes when key people change. Successful organizations recognize and embed the elements that drive a successful culture, regardless of the influence of individuals.

Generally, a successful culture involves a number of management-supported activities, such as expected behaviours, professional attitudes, positive language, supportive meetings, etc. Managers need to actively show that they follow these principles themselves to build trust. This takes time to develop because some individuals take longer to change and to believe in the approach.

It is essential for all stakeholders to understand the importance of positive attitude, collaboration, transparent working, and a supportive culture. This should encourage individuals to make suggestions, regardless of how unusual a suggestion may seem, so long as the goal is to improve the service.

The key elements of a continual improvement culture are:

• Transparency This encourages openness and trust.

• Management by example This should be displayed by all, especially leaders.

• Building trust The workplace should be a comfort zone where individuals feel supported to suggest, experiment with, and implement new ideas.

The following positive behaviours should be encouraged:

• Recruitment Hire the right sort of people with appropriate skills.

• Onboarding Brand values and expectations should be clearly and practically applied from the employee’s first days with the organization.

• Meeting culture Every participant should understand good meeting behaviour, including: timeliness, listening, focusing on the agenda, professionalism, and follow-up.

• Language and taxonomy Taxonomy can be used to drive and enforce positive behaviour, such as removing bias, ensuring common understanding of terms, and encouraging clarity and precision of language.

It should be made clear within the organization that every employee and stakeholder is expected to engage in continual improvement. Clarifying the following will also contribute to the success of a continual improvement initiative:

• How to raise an improvement idea.

• What happens to improvement ideas after they have been raised (are they reviewed and actioned)?

• What are the decision timescales and how will the outcomes be communicated?

• What are the other sources of input (e.g. customers, employees, business management, users, and service management teams)?

Collaboration and teamwork are more than empty buzzwords: they require an agreement on the definition of cooperation and collaboration. The behaviours necessary for effective teamwork also need to be defined, recognized, and reinforced.

Definitions

• Cooperation Working with others to achieve your own goals.

• Collaboration Working with others to achieve common shared goals.

With cooperation, there is a risk that individuals or teams who are cooperating work in silos. As a result, the individual or team goals are achieved but the organizational goals are missed.

From a business perspective, collaboration is a practice where individuals work together to achieve a shared goal or objective.

Cooperation and collaboration are vital for effective and valuable teamwork and service relationships. Collaboration is especially useful for creative and entrepreneurial work in a complex environment. Cooperation is important for standardized work with a clear separation of duties, especially where people from multiple organizations are working together. Collaboration is typically used in start-ups as the shared idea of the organization’s mission unites individuals and inspires them to work closely together. In attempts to adopt a start-up culture for larger organizations, leaders often aim to move to collaborative teamwork, but this often fails.

In a Harvard Business Review article entitled, ‘There’s a difference between cooperation and collaboration’, it was argued that ‘managers mistake cooperativeness for being collaborative’, adding that ‘most managers are cooperative, friendly, willing to share information – but lack the ability and flexibility to align their goals and resources with others in real time’.2

It is impossible to enforce collaboration, because it is based on shared goals and a high level of trust. Sometimes, it is more realistic to establish effective cooperation within and between teams using aligned, transparent, and integrated goals and metrics. Teamwork automation can be helpful, regardless of the location of team members. Metrics and automation, however, are tools used to achieve a goal, not a goal in itself. Cooperation and collaboration are based on the individuals’ and organizations’ relationships and cannot be limited to supporting components, such as controls or tools. Shared principles can be a foundation for effective teamwork and a starting point for its improvement.

2.3.5.1 Align with the type of work

Behavioural science enables us to define the work underpinning the operation of a service or product as either algorithmic or heuristic:

• An algorithmic task involves a person following a defined process that consistently follows a set of established instructions until the work is concluded.

• A heuristic task depends on human inventiveness and involves enabling a person to discover or learn something for themselves.

The service designer needs to understand the nature of the work on which their service and process depends. For instance, purely algorithmic tasks have predictable process paths with clear inputs, instructions, outputs, and branches at each step. Algorithmic activities can be implemented using a conventional flow based on reassignments and handovers between specialized silos supported by established knowledge bases of pre-defined instructions. However, the rigid structures that drive efficiency gains in algorithmic work can be too restrictive for heuristic or more creative work.

Loose controls should be applied when:

• complex issues need to be navigated

• new solutions are required for unmet business needs

• customers would respond more positively if frontline agents had greater flexibility.

In such situations, employees are enabled to improve the overall outcomes, which might not be possible for managers, owing to their relative distance from the day-to-day work. There cannot be a process or work instruction for every situation, so employees can add value through inventive and responsive heuristic work. Practices such as swarming (see section 5.1.4) and DevOps are examples of human-led and cross-functionally collaborative philosophies for work.

2.3.5.2 Learn through collaboration

Many companies benefit from the provision of opportunities for input and enhancement from the employee performing a specific task, even in situations where an algorithmic approach prevails.

In heuristic situations, new insights and solutions will frequently emerge during a project. Nevertheless, unless these new solutions are recorded for future application in equivalent situations, the work may be needlessly duplicated at a later time.

Collaboration frameworks should be used to capture, refine, and re-use any knowledge acquired. Consequently, it may even be possible to move some heuristic tasks into the algorithmic domain, removing repetitive or unproductive work from the system and allowing individuals to undertake more challenging and engaging heuristic work.

2.3.5.3 Servant leadership

Definition: Servant leadership

Leadership that is focused on the explicit support of people in their roles.

Effective leadership is important for the achievement of objectives, regardless of the organizational structure. For instance, servant leadership is more effective than command-and-control leadership in intellectually challenging work that requires agility and high velocity.

Servant leadership is an approach to leadership and management based on the following assumptions:

• Managers should meet the needs of the organization first and foremost, not just the needs of their individual teams.

• Managers are there to support the people working for them by ensuring that they have the relevant resources and organizational support to accomplish their tasks.

Servant leadership can often be seen in flat, matrix, or product-focused organizations. However, this approach can be applied to any organizational structure. The servant style of leadership inspires individuals to collaborate with the leader to become more cohesive and productive.

2.3.6 Customer orientation: putting the customer first

The need for everyone involved in the provision and consumption of a service to act responsibly, consider the interests of others, and focus on the agreed service outcomes is critical to the success of a service relationship. This can be called service empathy: a term which is often used in the relatively narrow context of user support and the related service interactions with the service provider’s support agents. However, service empathy should be expanded to all aspects of the service relationship.

Definition: Service empathy

The ability to recognize, understand, predict, and project the interests, needs, intentions, and experience of another party, in order to establish, maintain, and improve the service relationship.

Organizations and individuals involved in service management need to demonstrate service empathy. However, this should not be confused with the ability to share the feelings of others. A service support agent is not expected to share the user’s frustration but to recognize and understand it, express sympathy, and, vitally, adjust support actions accordingly.

Service empathy is one element of a service mindset. A service mindset includes shared principles that drive an organization’s behaviour and define their attitude towards the relationships affected by a service.

Definition: Service mindset

An important component of the organizational culture that defines an organization’s behaviour in service relationships. A service mindset includes the shared values and guiding principles adopted and followed by an organization.

A service mindset is an outlook that focuses on creating customer value, loyalty, and trust. An organization with this outlook aims to go beyond simply providing a product or service, it wants to create a positive impression on the customer. To do this, an organization has to understand and improve the customer’s experience. For more on service mindset, refer to ITIL® 4: Drive Stakeholder Value.

From a service provider perspective, service mindset is also known as customer orientation. A customer-oriented organization places customer satisfaction at the core of its business decisions.

Definition: Customer orientation

An approach to sales and customer relations in which staff focus on helping customers to meet their long-term needs and wants.

Management and employees align their individual and team objectives around satisfying and retaining customers. This is in contrast with a strategy where the needs and wants of the organization or its specific targets are valued over the requirements of the customer. Customer orientation has been studied comprehensively beyond the IT world. Essentially, it means observing the wishes and needs of the customer, anticipating them, and then acting accordingly.

Business relationship managers, service and support staff, and service owners are the roles that should be most aware of the customer’s needs. Customer-oriented strategies should encompass a training component for all employees.

Insight into the customer’s needs and the working practices of competitors can help to clarify customer orientation. In addition, a well-constructed customer survey can provide in-depth knowledge about how the organization has performed and how it may perform in the near future.

Organizations should consider the following when improving customer orientation:

• It is important to focus on value by considering customer needs and expectations, rather than focusing solely on formally stated requirements.

• Every customer is unique and has specific needs. These must be understood, prioritized, and communicated clearly to employees.

• The service, product, or maintenance process should be linked to the customer needs, which are based on a clear definition of the customer experience.

2.3.6.1 Customer experience

Adopting a customer-oriented strategy is key to success. Customer orientation puts the customer at the heart of every transaction. It shifts the organization’s focus from the product to the customer, meaning the organization must have a thorough understanding of the customer’s needs and expectations. Organizations must be able to deliver the strategy throughout the various stages of the service and customer lifecycle. From trainee to CEO, every employee in the organization must be completely committed to the strategy. Everyone has a part to play when it comes to customer service and retention.

The following steps can help an organization become customer oriented:

• Create a value proposition (VP) that sells the organization and its services This should be a simple statement of what is delivered to the customer and how it provides value. It should define, at a strategic level, the expected benefits the customer is being promised in return for their loyalty.

• Map the customer and user experience journeys This involves looking at the whole end-to-end experience of the service organization, as seen from the customer or user’s perspective. Touchpoints (defined as any event where a service consumer or potential service consumer has an encounter with the service provider and/or its resources) need to be understood, defined, and tuned to meet the needs of the service consumer.

• Recruit user-friendly individuals Hire people for their attitudes and train them in the necessary skills. Empathy, good communication, and problem-solving abilities are very valuable.

• Treat employees well How your employees feel at work has a major impact on how they deal with customers.

• Train individuals and teams All parts of the organization should gain a full understanding of the customer, product, and industry they support. Formal training and on-the-job coaching must also focus on soft skills: communications, teamwork, positive influencing, writing, business understanding, and administration.

• Lead by example Senior managers must embrace the customer-service concept and meet with users and customers periodically. Companies with the best customer-oriented culture value servant leadership, where senior managers exist to provide guidance and direction, but employees are empowered to make decisions on their own.

• Listen to the customer An honest appraisal of progress from customers is critical. This can be achieved by conducting surveys, having direct meetings, and gathering customer comments. Feedback is vital and should use a broad set of inputs and channels. Balanced scorecards of metrics can measure performance across a range of customer experience elements to drive improvements (e.g. key business outcome delivery, customer satisfaction, net promoter score, performance of the service level agreement, and service availability).

• Empower staff Ensure that customer-facing teams have the authority to implement requests, make changes, or resolve common customer complaints without further escalation.

• Avoid a silo mentality Encourage different departments and functions to work closely together.

• Design for humans Effective design of collaboration and workflow requires each interaction to align to the needs of the agents involved. Such a design should account for the information needed by each party at each step of the task. The service designer needs to gain a good understanding of the experience of everyone involved.

There are areas where technology can achieve results that humans never could; routine and repetitive tasks, for example, can be delivered by machines. Nevertheless, most working projects, teams, initiatives, and organizations require productive and positive interactions between individuals to succeed. Human interaction and communication are where real people still stand apart, ahead of the machines.

The ability to communicate effectively is a key business skill and is fundamental to success within service management. Good human communication is about being effective, efficient, responsive, and professional. Effective human communication is enhanced by establishing positive relationships that avoid unnecessary issues and stress, and it can form the basis for the successful delivery of services. In many cases, it requires a recognition of the intellectual and emotional needs of the people engaging in the communication. Service management, sales, and customer support roles depend upon building positive relationships which include trust, empathy, proximity, and shared goals.

Service management professionals require the ability to manage relationships with colleagues and team members to achieve business goals. They also need to be able to build and maintain effective and positive relationships with customers.

It is important to follow a project or service operation’s plans. Good communication ensures plans are followed and do not fail due to missed or mixed messages, inadequate information, or unclear and contradictory expectations. Changes are inevitable in today’s fast-moving world, and certain individuals can inspire and drive others to enable change to occur. People in this sort of role need to question issues and suggest improvements. They also need to be able to see a situation from different perspectives, and to react quickly to negate potential issues. Good communication enables all this to happen and is good for business.

2.3.7.1 Communication principles

Individuals at work need to communicate regularly and effectively with others, which requires a rounded set of communication skills. Some people are naturally better communicators than others. Regardless, every stakeholder needs to achieve a basic level of competence and effectiveness in communicating.

Communication requires an acknowledgement of the perspective of others. Good communication requires people to be flexible enough to use appropriate content and tone to achieve the desired objective.

The fundamental principles required for good communication can be summarized as follows:

• Communication is a two-way process Successful communication is an exchange of information and ideas between two or more parties.

• We are all communicating all the time People convey messages about their mood, attitude, and emotional state through the use of language, tone of voice, body language, dress, and manners.

• Timing and frequency matter Successful communication needs to consider the best time to make contact.

• There is no single method of communication that works for everyone It is important to recognize and utilize different preferences and methods.

• The message is in the medium Choose a method of communication that is appropriate for the importance of the message that is being communicated. A minor point may be communicated via messaging or email. Big issues or questions require direct discussion and should not be carried out via email.

Understanding, recognizing, and implementing these principles is essential when building positive relationships with colleagues, customers, and stakeholders. Good communications help to get the job done, ensuring a pleasant and rewarding exchange for all concerned.

Changing an existing culture, especially with people who are autocratic and not very collaborative, is challenging and requires bravery, commitment, and persistence. In addition, there is a need for ongoing and visible support from senior managers and leaders from across the organization. Transparency, for example, can often be mistrusted and misunderstood, particularly in environments where individuals, owing to previous bad experiences, feel uncomfortable about sharing information.

Managers need to lead by example to show that they are serious about the need to change and to be open and transparent, as well as to share ideas and information. In order to build trust, everyone needs to follow through on their promises. All ideas should be visibly reviewed, responses given within agreed timeframes, and the participants thanked and rewarded.

The chances of successfully developing a new culture can be improved by using tried and tested methods from the body of knowledge around organizational change management (refer to ITIL® 4: Direct, Plan and Improve and to the organizational change management practice guide).

The ITIL story: Developing team culture

|

Solmaz: At Axle, we consciously work on our culture. We promote values that include trust, collaboration, respect for others, and courage. New employees need to be the right cultural fit that respects and works to Axle’s values and beliefs. |

|

Alice: As part of our onboarding process, new employees are introduced to Axle’s vision, values, and ways of working. We have a shared continual improvement register, and we encourage everyone to contribute to it. We want the team to be open, comfortable with suggesting ideas, and responsive to feedback. |

|

Reni: I have created a virtual Kanban board so all our team members and stakeholders have visibility of our backlog, progress, and risks. |

|

Solmaz: We will also celebrate achievements, such as the first bike hire! This acknowledges the hard work of the team, incentivizes our goals, and encourages a positive work environment. |

The service management domain is changing in fundamental ways. It is transitioning away from a mechanistic point of view to using highly empowered and self-organizing teams. Consequently, organizations are grappling with the integration of multiple ways of working.

Successful organizations think holistically about the four dimensions of service management (organizations and people, partners and suppliers, value streams and processes, and information and technology) when designing and operating products and services. They are able to create a culture of cooperation and collaboration, often breaking down silos and aligning or sharing goals across multiple teams. Such organizations are alert to employee morale and satisfaction, recognizing that internal stakeholders are as important as external ones.