Case Studies

This appendix contains four cases. With each of these, perform the same steps that would be performed if you were working on a Lean project in an organization:

- Determine the metrics that should be included in a project charter for improvement of the process described in each case.

- Draw a value stream map, and then calculate these quantities:

a. Lead time for each process step

b. Total process lead time

c. Total value-added time

d. Total non-value-added time

e. Value-added ratio (VAR)

- Find the waste in the process.

- Devise improvements to reduce the waste and improve the metrics determined in the first step.

- Draw the value stream map of the process as if the improvements in the previous step had been made.

- Create a list, in order of priority, of the improvements identified and how they should be addressed (i.e., which Lean tools would be appropriate?).

One of the cases also lists additional questions that direct a reader toward problems and possible solutions for that particular context.

The lead time of all steps might not be clear in some instances. In those cases, make reasonable assumptions. Remember that value stream mapping can be considered a rough tool to point us in the right direction, and even with some error in lead time measurements, the value stream map often points us toward the same improvements.

Garth’s Gardens

Garth’s Gardens is a premier landscaping service and garden store in Richmond, Virginia. The company is owned by Garth Gardenia, and it sells plants and landscaping materials from its garden store to walk-in customers. In addition, Garth employs landscape designers and construction workers who design and install landscaping for residential and commercial clients. Garth was particularly concerned with ensuring continued business in landscape design and installation because this was the source of significant revenue, as projects brought in $50,000 of revenue on average. Being a reasonably small company, Garth could not afford poor performance in this part of his operation because the loss of even one project would severely impact on his profits: $50,000 was not an inconsequential portion of Garth’s revenues. Moreover, many of the landscape designers and construction workers were on salary and thus represented fixed costs that needed to be covered regardless of business volume.

Although Garth advertised in the Yellow Pages and in mailings, he realized that most of his business came from repeat customers and friends and acquaintances of current customers who were particularly impressed with the visual appeal of a project that Garth’s company had previously completed. Besides the aesthetic attraction of Garth’s work, word of mouth from former clients was important—although a project might look beautiful, people were often quick to communicate any problems experienced with the project. Thus every aspect of interaction with the customer needed to go smoothly. The most common perception of a customer’s experience with a construction project is that once a contractor has the job, it was often difficult to get the contractor to finish the job in a timely manner. Often, clients felt as though they were in competition with other jobs that the contractor had on his or her plate and that they were given low priority. Garth was particularly sensitive to this and did not want his clients to relate such experiences to other potential clients.

Garth’s obtained landscaping projects through phone calls from potential clients who would call to ask for quotations. Some of these people were former clients of Garth’s, some had heard of Garth’s through word of mouth from former clients, and others might have found Garth’s Gardens in the telephone book. Garth was particularly concerned with being prompt in responding to queries from potential clients about landscape design because he realized the popular conception that contractors had little regard for getting jobs done on time and being slow to respond might cement in potential clients’ heads that Garth’s company was nothing but a typical contractor in that regard. Accordingly, if another contractor was quicker to respond, they might steal the business from Garth. Thus Garth was interested in reducing the amount of time it took to respond to customers’ requests for proposals and price quotations on landscaping designs and installations. A faster response to potential customers’ inquiries would communicate a sense of competence and professionalism to the customer that would translate into winning a higher percentage of the projects for which they submitted quotations to the clients. Garth was also interested in developing a relationship with the client during this process: Even if Garth’s did not win the contract in a particular instance, then perhaps making a favorable impression could translate into business at a later time. Moreover, Garth felt that it was important to visit customers at their house or place of business because, first, Garth felt that interaction on the customers’ site rather than in a conference room at Garth’s store better facilitated the building of relationships and, second, this gave Garth’s representatives better information about a customer’s yard and thus Garth’s representatives could give the client better advice on potential alternatives for achieving the customer’s landscaping goals. In addition, this allowed Garth’s to determine up-selling opportunities—that is, opportunities to suggest to the client future projects that Garth’s might perform.

Because this process of developing new business is so critical to the financial success of Garth’s operations, and because reducing the time to prepare and develop quotes for customers was one of the important metrics in the process, Garth’s managers decided to improve this business development process using the Lean methodology. The two most prominent employees involved in the generation of a quotation for any particular client were the client administrator (CA) and one of several sales associates (SAs) that Garth employed. The CA worked full time in the Garth’s Gardens office building and, among her many tasks, received the initial calls from clients who wanted Garth’s to give them a quote on a particular project. During that initial call from the client, the CA would record the client’s contact information and general details about the type of project in which the client was interested. That call would usually take about 5 minutes. The CA would batch the client requests, and approximately every 24 hours, she would determine which SA would receive each client request based on the type of project the client was considering. (The requests would, therefore, average 12 hours before they were passed on.) The CA felt that it took her less time to determine which SA should receive each request, and she did a better job when she could set a block of time aside to “get her mind into the job.” She could make the assignment decision for each client request in about 5 minutes. Batching, or delaying handling the customer requests, also allowed the CA, in her opinion, to comfortably handle her other tasks without needing to multitask. Each potential client’s name, contact information, and a brief description of their project were put into the assigned SA’s in-box after the CA had made the assignments.

Often, the SAs would not be at Garth’s retail site but rather on-site with clients reviewing potential business. For this reason, the paperwork that the CA filled out with the client’s information would remain in the SA’s in-box, on average, for 12 hours. Also, while clients were believed to be of great importance, the organization was not sensitized to handling the potential leads in an ASAP fashion.

Once the SAs got to their in-box, it obviously did not take them long to retrieve the paperwork (5 minutes or less). Once each client’s request was retrieved, it would take on average 12 hours to contact the client: Some of this was due to telephone tag, but much of it was just being sidetracked by other tasks, such working on other clients’ requests. Once contact was made with the client, it took about 1 day (1,440 minutes) before the SA met with the client. This wait time was due partially to the SA’s schedule and partially to the availability of the client.

The meeting with the client usually took about 1 hour, and the SA would make notes about the project during that meeting so that he or she could accurately estimate the cost of labor and materials. The SA would also take this opportunity to suggest alternate ways to accomplish the client’s goals. Sometimes, what the customers conceived as an initial design concept was not the most effective, economical, or aesthetic approach to the project. This is where the expertise of Garth’s could in many cases offer the client a better way to do the project that was both more satisfactory to the client and, sometimes, more economical.

Usually, about 1 day after the meeting with the client, the SA would sit down to prepare a handwritten version of the quotation for the client based on the notes that he or she had taken the day before. This took about 60 minutes. SAs were not always on-site at the Garth’s retail store when they prepared these quotations, so it would take some time (on average about 4 hours) before the SA would get back to Garth’s to put the drafts into the CA’s in-box.

The CA tended to batch the typing of the electronic version of the quotations from the SAs’ handwritten notes. For this reason and also because of being interrupted by other tasks, it would take about 12 hours before the CA got around to typing a quotation. It took on average 1,440 minutes (1 day) to finish typing the quotations for a two reasons: (1) Several quotations had usually piled up before the CA started working on another batch, and (2) the SAs’ handwriting could sometimes not be read by the CA, in which case the CA would need to contact the responsible SA and resolve the issue. Contacting the SAs in the field was not always easy because they were often meeting with clients.

After the CA typed the quotations, she would put them in the in-boxes for the responsible SA, who after about a 12-hour delay would review it for accuracy. Again, the delay was largely due to the fact that the SAs spent most of their time in the field and sometimes were absent from the office for a reasonably long period.

After reviewing the typed quotation and noting required revisions, the SA would put the marked-up copy in the CA’s in-box. Changes were sometimes due to the SA having had more time to think about how to approach the project and the bidding of it, and sometimes it was because the CA had misinterpreted what the SA had written. Getting the marked-up copy out of the in-box took the CA little time. The time to revise the report in the computer was usually short. The CA tended to do these corrections right away, since they were easier than interpreting the SAs’ notes when the first draft was typed.

At that point the CA indicated in the computer system that a quotation was finalized, and she would print out a hard copy. Since the SA most often had left the office by then to see other clients, that hard copy would remain in the SA’s in-box until he or she returned to the office, which would usually be in about 1 day (1,440 minutes). Upon retrieving the revised proposal from their in-box, SAs would again make an appointment with the client to deliver the proposal. It, again, took on average a day to get in touch with a client, and then another day, on average, before the meeting would take place due to the availability of the SA and the client. Finally, delivering the quotation in person to the client and explaining it took the SAs about an hour. A summary of the process steps is shown in Figure 46.

Process Steps for Developing a Landscaping Proposal

| Step number | Description | Responsibility |

| 1 | CA receives call from client. | CA |

| 2 | CA assigns projects to SAs. | CA |

| 3 | CA distributes hard copies of client contact information to SAs’ in-boxes. | CA |

| 4 | SA retrieves the client information from his or her in-box. | SA |

| 5 | SA contacts the client to arrange an appointment. | SA |

| 6 | SA visits the client site. | SA |

| 7 | SA prepares handwritten draft of proposal. | SA |

| 8 | SA turns draft of proposal into CA’s in-box. | SA |

| 9 | CA retrieves drafts from her in-box. | CA |

| 10 | CA types drafts. | CA |

| 11 | CA places drafts in the SA’s in-box. | CA |

| 12 | SA reviews the draft and makes corrections. | SA |

| 13 | SA puts revised draft in CA’s in-box. | SA |

| 14 | CA revises draft in computer and prints it out. | CA |

| 15 | CA puts revised draft in SA’s in-box. | CA |

| 16 | SA retrieves revised draft. | SA |

| 17 | SA schedules appointment with client. | SA |

| 18 | SA visits client and delivers proposal. | SA |

Figure 46. Garth’s Garden quoting process.

Il Negozio Internet Prosciutto Sales

Il Negozio is an Internet retailer of fine Italian foods with offices in Williamsburg, Virginia. Its sales were almost solely through the Internet, and one of its featured products was dry-cured hams from central and northern Italy. Although it sold lesser grades of prosciutto, its most expensive sold at a retail price of $100 per pound. Whole legs of prosciutto weighed between 10 and 15 pounds, so purchasing an entire ham could cost a customer as much as $1,500. Although some wholesale clients’ sales volumes could justify a purchase in such a quantity, most of Il Negozio’s clients were individuals who wanted, and could only afford, a much smaller portion of prosciutto. Smaller, vacuum-packed portions of prosciutto were easy to ship via UPS in Styrofoam boxes with a dry ice block to protect the perishable prosciutto.

Il Negozio had enjoyed rapid growth, as many people of Italian descent who lived in the United States discovered its products. In addition, Italian food was popular with those who traveled to Italy on vacation or who otherwise found out by word of mouth about the unique, high-quality foods offered by Il Negozio.

Il Negozio offered ham for sale in multiple packaging options. A customer could buy a full ham leg, but most customers wanted a smaller quantity of ham, and so Il Negozio offered 4-ounce and 8-ounce packages of presliced ham. Il Negozio bought prosciutto directly from producers in Italy, and because the producers would only ship in large quantities, Il Negozio was required to purchase full hams rather than partial hams or prepackaged slices. Preslicing prosciutto in Italy also presented quality concerns due to the perishability of the product. Il Negozio therefore needed to have the full hams sliced and packaged after it received the hams in order to sell ham in quantities other than full legs.

It was currently necessary for Il Negozio to outsource the slicing of ham to another company, mostly because ham could be sliced only at a facility that was approved for the processing of food by the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Il Negozio currently had neither that certification nor a facility for slicing. The slicing subcontractor was located in Virginia Beach, Virginia, approximately a 2-hour drive from Williamsburg. Given the congestion on Interstate 64, which connected Williamsburg and Virginia Beach, that trip could take much longer if the tunnels in the Hampton Roads area were backed up, which they often were.

It was important to quickly receive, slice, and record the inventory as available for shipment in the computerized inventory system because the prosciutto was available for purchase on the Internet site only after the entire process was completed. If Il Negozio ran out of ham before the process was completed for the next batch of ham to be sliced, then the Internet site would show that the product was out of stock. Thus, although Il Negozio physically owned the ham, if it was still in the slicing process, Il Negozio’s website might show the ham as out of stock, thus causing customers either to be dissatisfied or to shop elsewhere for ham. The importance of quickly getting ham sliced and into inventory was increased because ham represented such a large investment: Unless the ham was ready to sell, it represented a significant investment from which Il Negozio could get no financial return.

Il Negozio received ham with other products in refrigerated containers. The first step in the process was to unload the containers. Typically Il Negozio received 20-foot-long refrigerated containers (or “reefers,” as they are known in the logistics business) that contained many items besides the hams. Unloading the reefer took about 4 hours, of which 20 minutes was for the ham.

After the hams and other items were unloaded from the container, Dana, the warehouse supervisor, would notify Kevin, who worked in an upstairs office, that the shipment had arrived. Typically, Dana could let Kevin know that the container was unloaded within 20 minutes of the crew finishing, although sometimes emergencies came up that delayed her from alerting Kevin. When Kevin became aware that a shipment of ham had been received, he would then create a work order in the computer system, which was the official authorization needed to allow the ham to be shipped out to Il Negozio’s slicing subcontractor in Virginia Beach.

Once the work order was created, Kevin would need to contact Dana (downstairs) to tell her that it was okay to proceed with the next step, which was to weigh the ham, add the weight onto the work order record in the computer system, and then pack the hams onto a pallet. Sometimes Kevin would find it difficult to contact Dana if she was busy or on the phone, and sometimes he would get sidetracked by other tasks so that he was not able to immediately get in touch with Dana after he created the electronic work order. Due to these types of delays, it would typically take 4 hours before Dana started with the process of weighing the hams, which took 80 minutes. This time also included the time required to enter the information into the computer and load the hams onto a pallet.

After this step was complete, then the paperwork needed to be printed in hard copy to accompany the order to the subcontractor, so Dana would contact Kevin (upstairs) who would print out the paperwork. Making contact with Kevin was usually fairly quick at this point in the process, taking only 5 minutes. Printing the paperwork took approximately 15 minutes.

Unless it was near the end of the work shift, one of Dana’s crew would then drive the hams to the subcontractor in Virginia Beach, which took 2 hours. When researching this process, Kevin and Dana found that the subcontractor waited 10 hours, on average, before starting to slice the ham. It was unclear to Kevin and Dana why this delay occurred.

Once the slicing step commenced, it took approximately 4 days (5,760 minutes) for the subcontractor to finish slicing and packaging the typical shipment of ham (the time required depended on the size of the shipment). Kevin and Dana had done a little research about this step to uncover some of the details of how slicing and packaging were done. This step was influenced by FDA regulations regarding the safe handling of perishable food products. Those regulations stipulated that the ham could only be out of refrigeration for a limited period of time, and the slicing and packaging machine were not in a refrigerated area. Because only one operator was assigned to the slicing and packaging operation, he or she would slice a certain quantity of ham and then stop the slicing process in order to vacuum pack what was just sliced. Then the operator would return the finished product to refrigerated storage. The size of the batch of ham that could be sliced needed to be small enough such that the total elapsed time of slicing and packaging the ham was less than the maximum time allowed by the FDA for the ham to be out of refrigeration. Thus this step was slowed down because one worker was operating two workstations, as well as performing all the material handling.

After completion of the slicing and packaging operation, the subcontractor then needed to count the packages of ham, weigh the ham, and finally pack it into boxes. This process took approximately 2 hours, but often there was a large time lag before this step of the process commenced; it was not clear to Kevin and Dana why this was the case but they guessed that it was because the subcontractor did not put a priority on their order versus other operations that the subcontractor performed. Weighing the ham at each step of the process is important because the ham is valuable and prone to theft. The Italian hams are so cherished that every part of the ham is used. Il Negozio required that the subcontractor return even the fat that they trimmed from the ham because Il Negozio could sell this to customers who used it to season the recipes they cooked.

After the order was boxed and ready to go, it would take the subcontractor approximately 6 hours before they got around to calling Il Negozio to let them know that the order was complete and to arrange for a delivery time. That call took only 5 minutes. The subcontractor’s truck would then leave the facility between 12 and 24 hours later, and the drive from Virginia Beach to Williamsburg would take about 2 hours. Upon arriving back at Il Negozio with the ham, it would take the driver about 10 minutes to find Dana to let her know that the truck had arrived and was ready for unloading. Unloading the truck and getting the ham into refrigerated storage took approximately 1 hour.

After about 4 hours, the packages of ham would be counted and weighed one more time by Dana or one of her crew. This took about 90 minutes. After being delayed on average by 15 minutes for other tasks and interruptions, Dana would take about 15 minutes to fill out a receiving report that verified the count of ham packages and the total weight. The next time Dana went upstairs to the offices, she would take the receiving report with her and hand it to Kevin or put it in Kevin’s in-box if he was away from his desk. Kevin had authorization to enter this data into the computer, while Dana did not. Kevin would take about 90 minutes to get around to this task, and then after another 5 minutes on average for interruptions, Kevin would update another computer system that made the ham available online for Internet shoppers to purchase.

A Supply Chain for Automobile Doors

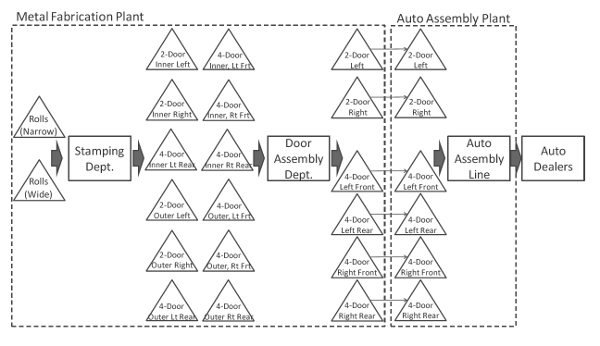

Figure 47 shows the supply chain for automobile doors. The general steps of the process are the following:

- Steel parts are stamped out of coils of steel.

- The steel parts are welded together to make door assemblies.

- The door assemblies are installed on automobiles.

The first two steps are performed in what was called the “metal fabrication plant.” Within that plant, parts were stamped in the “stamping department” and they were welded together in the “door assembly department.” The third step occurred in the assembly plant.

The assembly plant produces both two-door and four-door vehicles. Thus the auto assembly plant requires six different types of doors:

- Two door, left

- Two door, right

- Four door, left front

- Four door, left rear

- Four door, right front

- Four door, right rear

Both the metal fabrication plant and the assembly plant operated exactly the same number of days each year (on exactly the same days) and the same hours per day. Specifically, both plants worked 220 days per year and 16 hours per day.

The following paragraphs describe the supply chain structure and management decision policies in each supply chain link:

- Steel manufacturer. This plant supplies two types of rolls of steel to the metal fabrication plant (the next link in the supply chain), one of narrow width (0.9 meters wide) and one wider roll (1.4 meters wide). Both types of steel are 1.3 millimeters thick. The first roll is used to stamp inner door panels, and the second type of roll is used for outer door panels in the metal fabrication plant. The wide rolls weigh 25 tons and the narrow rolls weigh 15 tons. During the previous year, 5,000 wide rolls were used and 10,000 narrow rolls were used. Production rates at the assembly plant this year and next year were anticipated to require steel at this same rate.

- Transportation from steel manufacturer to metal fabrication plant. The current policy was to load trucks with either two large rolls or three small rolls on a truckload. Weight restrictions limited trucks to carry no more than 55 tons of steel. Furthermore, the truck had the capability of hauling no more than three rolls at a time due to the length of the trailer bed. (Any combination of three rolls was possible because the rolls were the same diameter although different widths.) The fixed cost for each truck delivery was $800 and the variable cost per ton was $0.50.

The following five steps are all within the metal fabrication plant, which stamps metal parts for doors and then produces an assembled door by welding one inner panel together with one outer panel:

- Incoming raw materials inventory of roll steel. Rolls of steel were stored here when they were received from the steel plant.

- Stamping department. The schedule for stamping parts was the same order as indicated by the triangles after the stamping department in Figure 47, which represent work-in-process inventory: First, the parts in the first column were produced, from top to bottom, then the parts in the second column, and then the same sequence was repeated again. (This is called a cyclic schedule.) One press line was used for producing all these parts, although other press lines were capable of producing these parts as well. Changing the dies in the presses from those required for one part to those dies required to produce the next part in the sequence required 4 hours (i.e., this was changeover time). This department produced panels (either inner or outer panels) at a rate of 400 per hour. Each wide roll of steel yielded 150 outer panels and each narrow roll of steel yielded 75 inner panels.

- Inventory of stamped inner and outer panels. The inner and outer panels were stored here once they were stamped. Those inventories are designated in Figure 47 by the triangles.

- Door assembly department. The assembly of each of the six styles of doors required two parts, an inner panel and an outer panel. The operation cycled among the six parts listed in Figure 47 following the sequence from top to bottom, and then it repeated. Changeover time is required to change the operation from the production of one part to another, which takes 4 hours. This operation produces doors at a rate of 200 per hour. Each batch of doors is completed before it is transported to the subsequent inventory step.

- Inventory of assembled doors. Finished doors were stored here until it was time to ship them to the assembly plant. This inventory is designated by triangles in Figure 47.

The following two steps were within the auto assembly plant:

- Incoming raw materials inventory of assembled doors. Doors were stored here when they were received from the metal fabrication plant until needed at the assembly line.

- Auto assembly line. The assembly line produced cars at a rate of 60 per hour, and on average over a month, 50% of the cars were two-door models and 50% of the cars were four-door models. The percentages of two-door models and four-door models varied considerably, however, from hour to hour and shift to shift. It was very difficult to forecast how many two-door models and how many four-door models would be made even an hour in advance: The auto assembly plant was notorious for continually changing the schedule. The schedulers claimed that they needed such flexibility to respond to dealers’ last-minute orders. Such responsiveness, they claimed, was a competitive advantage for the company versus other auto manufacturers.

Additional Questions

- Suggest a revised shipping policy (quantity of each type of roll of steel that should be shipped in a truckload) that could both reduce annual trucking cost from the steel plant to the metal fabrication plant and also reduce the average inventory level of raw materials at the metal fabrication plant.

- How much time is required to go through the cyclic schedule for the stamping department in the metal fabrication plant as described in the case?

- How much time is required to go through the cyclic schedule for the door assembly department in the metal fabrication plant?

- It has often been observed that the inventory between the stamping department and the door assembly department in the metal fabrication plant is out of some part that is currently needed in the door assembly department while there are large inventories of other parts. Suggest changes that could be made in the stamping department schedule, changeover times, or equipment investment to reduce this lack of coordination or, in other words, reduce excess coordination inventory, and describe conceptually how your suggestion would increase synchronization between the two departments.

- An engineer visited a Toyota assembly plant and saw a different method for assembling the inner panel with the outer panel. Rather than a big machine that required a setup, it was a flexible machine that could make two-door and four-door doors in any sequence, and it was small and simple enough that it could be placed right beside the assembly line in the assembly plant. The machine could produce doors at a rate of 95 doors per hour, so that one machine on each side of the assembly line would have sufficient capacity. What are the advantages and disadvantages of acquiring this equipment?

- Suppose that the door assembly department intended to schedule their production for each shift to be exactly the quantities of two-door doors and four-door doors that the assembly plant had used the previous shift, thus implementing a pull system (a work shift is 8 hours long). Also under this proposal, the inventory after the door assembly department would be eliminated so that door assemblies made by the door assembly department would be immediately shipped to the assembly plant. How would the door assembly department operation need to be improved, and what change in management of the inventory between the stamping department and the door assembly department would be required to accommodate a varying schedule in the door assembly department? Why?

Figure 47. Supply chain diagram.

Alvin’s Auto Parts

Alvin owned and operated an auto parts store in Williamsburg, Virginia, which was associated with the Regional Automotive Parts Association (RAPA). All parts sold at Alvin’s were supplied by RAPA. Upon entering Alvin’s store, one might first be struck by the peculiar ambiance of the store, which was in stark contrast to the national car parts retail chains that have sprung up over the past two or three decades. Instead of a sparkling clean retail space, Alvin’s store was dimly lit and one might suspect that it had been a long time since the store had received a thorough cleaning: The parts racks seemed to be covered with a thin coat of grease or machine oil, and greasy fingerprints were visible on some boxes. This was a place where somebody who prided themselves on being called a grease monkey would feel comfortable hanging out on one of the stools at the counter that were upholstered in a shiny vinyl with RAPA’s logo. Some of the upholstery was ripped, perhaps by tools carried in customers’ pockets.

While not a sparkling environment, one of Alvin’s competitive advantages was that he did not mind placing special orders for customers, and customers found doing business with Alvin advantageous when they were trying to track down hard-to-find parts. It was probably true that Alvin’s willingness to special order parts was one aspect of his business that helped him to secure repeat customers, who after purchasing a part via a special order would then return to purchase other, more common parts from Alvin. Alvin had reluctantly agreed to let some local college students help him with his special order process. Alvin really did not see that much wrong with it, but he liked to help support the local school, so he agreed to the project. In discussions with the students, who were taking a course in Lean, Alvin agreed that reducing the time to get special order parts would be an advantage to his customers and satisfy them to a greater extent, but he did not see much reason to investigate the special order process: He had been fulfilling special orders for 25 years now and he did not think there could many opportunities for improvement here. After all, what did these kids know about auto parts? In any case, although he did not see much point, he relented to answering questions about this process and letting the students observe it.

The Special Order Process

The process for fulfilling a special order started when the customer came into the store and, perhaps, after finding out that the particular part they were searching for was not stocked on an ongoing basis, Alvin (or whoever was at the counter) would handwrite the customer’s order on the closest scrap of paper. The sales associate would ask the customer for their name and phone number and, after consulting the catalogs, would write down the part number, supplier, and retail price on the scrap of paper. It would take between 2 and 15 minutes to write down the order information depending on how difficult it was to locate the part in the catalogs. After taking a special order, it would be placed on the corkboard immediately, which was located 25 feet from the sales counter, unless another customer was waiting at the sales counter to be served, in which case the order slip would be taken to the corkboard at a later time. It took about 15 minutes, on average, for the special orders to find their way to the corkboard.

Customers would often inquire about an estimated delivery time. Alvin did not have electronic access to the RAPA distribution center inventory, and so he always quoted one week from the upcoming Thursday as the delivery date, although he knew sometimes it would take longer if the distribution center was out of stock.

Although replenishment occurred daily from RAPA for parts that were stocked by Alvin on an ongoing basis, Alvin would place special orders only once a week, on Thursdays, because of the time involved. Every Thursday morning, Alvin would accumulate the special order slips from the corkboard and place an order with RAPA. Actually, it was probably more accurate to say that Alvin would start accumulating orders on Thursday morning. While there were approximately 10 special orders per week, it would take Alvin 4 hours, on average, to put the orders together because he also needed to staff the sales counter on Thursday mornings besides placing special orders. In addition, the special orders from the past week would arrive on Thursdays, and so Alvin worked with the newly arrived merchandise over the course of the morning, which is discussed later. The inventory levels for the items that Alvin always stocked were recorded in the point-of-sale (POS) computer system. Every time an item was sold, the inventory quantity recorded in the computer system would be adjusted downward accordingly. Inventory was replenished using a reorder point method: When inventory decreased to a specified threshold level, then a certain quantity (which was established in the computer system) would be ordered automatically from the RAPA distribution center. Alvin’s POS system, which was supplied as part of his agreement with RAPA, was tied electronically to RAPA’s computer system and these orders were placed automatically. The automatic orders generally were received 2 days after they were placed, unless the RAPA distribution center was out of stock. Special orders were handled differently, however. Alvin would accumulate all the information from special order slips from the past week by writing that information, by hand, on an 8.5-by-11-inch piece of paper before faxing it to RAPA. The list of all the parts would take about an hour to put together, if Alvin worked on it without interruption. However, interruptions usually caused this task to take most of the workday. Alvin would generally fax the special order list to RAPA before he left work on Thursday, which was usually around 7:00 p.m.

Special orders took one week to arrive, coming in on the following Thursday. The RAPA delivery truck would arrive at the truck dock door on Thursday and drop off a pallet of goods, or however many pallets were required in total by the regular and special orders combined. The next step was for Alvin (or one of his associates) to receive the goods, which meant that he needed to enter the item number and quantity of each item received into the computer system. This step was important because it resulted in correctly updated inventory levels in the POS computer system. This process could be done either by using the paper packing slip, if you trusted that document to correctly reflect the quantities actually received, or by manually scanning each item on the pallets with a bar code reader and entering the quantity of each item as confirmed by a manual count. Alvin preferred the latter method to ensure accurate inventory levels and to make sure that he received what RAPA would later bill him for. This task would commence when it occurred to Alvin that the time was right—that is, when he remembered that it needed to be done and counter business was slack. About 4 hours generally lapsed before the receiving step started. Receiving both regular and special orders, which was done simultaneously, typically took about 2 hours. Alvin needed to handle both types of items at the same time because the special and regular orders were not separated on their own pallets.

After entering the merchandise into the POS computer system, Alvin would identify the items that were special orders so that he could set them aside. To do this, he took the packing slip, which came with the shipment, and compared each item on it with the handwritten order slips on the corkboard. Alvin took approximately an hour and a half to do this reconciliation, after which he would rummage through the pallets to find the special order items so that he could put them on his shelving unit for special orders. Alvin did not do this right away for several reasons. He did not like to sort through the pallets of items because he routinely would miss the special order items and need to go back though the pallets multiple times. So he procrastinated before starting on this step. Also, he would be interrupted by customers while he was searching for the special order items, which would delay him. Alvin estimated that he would wait approximately 8 hours on average before he started searching for special order items and that it took him 3 hours to complete that task. He thought he could find all the special order items in about 1.5 hours if he was not interrupted, but he felt that he needed to give customers at the sales desk priority attention.

After the special order items were found, they would be stacked on the floor besides the recently received pallets. Once they were all identified, they would be placed on the shelving unit for special orders. Alvin would assign one of his associates this task. (Alvin did not like doing this step because it involved carrying parts by hand about 50 feet to the shelving unit, and as Alvin was getting on in years, he could not afford to have his back go out on him.) This would take about 15 minutes, but it did not usually happen right away because it might take Alvin a little while to remember that it needed to be done and all the sales associates might be needed at the counter.

Next, Alvin or one of his sales associates would call the customers whose orders had arrived. This would be accomplished by pulling the paper order slips down from the corkboard as the incoming items were being reconciled with the packing slip. Then that stack of order slips would be placed by the telephone until such time as somebody could make the calls. Ordinarily, about 8 to 12 hours would pass before somebody got to that job. It would be a different person who made the calls each week, and Alvin would designate that person when business at the counter lightened up and he remembered that somebody needed to do it. Each call took about 2 minutes. Then the slips would go back onto the corkboard. Sometimes customers’ phone numbers had not been recorded or were apparently not recorded properly, since some calls ended up in wrong numbers or to phone numbers that were out of service. Even when phone numbers were recorded, they were sometimes difficult to read because of sloppy handwriting.

When a customer would arrive to pick up their order, they would inform the sales associate at the sales counter, who would then go to the corkboard to look for an order slip with that customer’s last name on it. More than occasionally, the order slip would be difficult to locate due to poor handwriting, in which case the sales associate would return to the sales counter to verify the customer’s last name and perhaps ask them what part they had ordered. Upon verifying the last name and finding the order slip, or if the order slip could not be found, the sales associate would start looking for the item on the shelves for special orders. If the order slip was found immediately, then locating the part could take as little as 4 minutes. However, locating the part could take as much as a half hour. Sometimes the part was difficult to find and sometimes the part had already been sold and it took the sales associate a while to conclude that the part was not on the shelf.

Customers might call to inquire about the status of their order before the part had arrived. Many times this was due to the part not arriving in the quoted amount of time. Some customers were very impatient and called often. Finding a customer’s order status involved searching the orders on the corkboard and the shelves. This could take as much as 15 minutes per inquiry.

Further Investigation

The student team learned the information about the special order process discussed thus far in the case by observing Alvin and asking him the basic questions about lead time and cycle time that they would need to construct a value stream map. As the students began to construct the value stream map, questions naturally occurred to them that they had not thought to ask before. In subsequent interviews with Alvin and learning about the process by standing in a circle and studying it for long periods of time, here are some other data that the students collected.

Observations From Standing in a Circle

- On two occasions team members observed customers coming in to pick up their parts. After spending 5 to 10 minutes looking for the parts, Alvin and one other sales associate announced to the customers that they could not find the parts and that they must have already been sold. One customer asked why their part would have been sold within 1 day of when it arrived and why the store had not held on to the part at least 1 day. Alvin said that if customers wanted the store to keep a special order part, then they need to pay for it up front and notify the salesperson that the part should be held for them. Otherwise, the policy was to sell the part to the first customer who asked for it.

- Although Alvin had said that approximately 10 special orders were placed a week, the students observed on three different occasions, at different times of the week and on different weeks, approximately 30 special order slips on the corkboard.

- Observations of the order slips on the corkboard revealed that not all slips contained all the information that Alvin would collect if he were taking the order. For some reason, some information was missing on some orders.

- Observations of the order slips on the corkboard raised questions about the legibility of handwriting on many of the slips. Legibility caused problems that have already been mentioned, as well as difficulty reconciling the received parts with the handwritten part numbers on the order slips.

- The organization of the corkboard and the order slips did not lend itself to easily identifying how far a particular order had progressed in the process. For example, it was difficult to determine whether an order was yet to be placed with the RAPA distribution center, had been ordered from the RAPA distribution center, had been received, or had already been delivered to the customer.

Answers to Questions Asked of Alvin

The student team asked the following questions, and received the corresponding answers:

Q. Why do you place orders once per week? Would RAPA object to a greater number of special orders per week and fewer items per order?

A. We have always placed special orders once per week. I have never asked RAPA if they would process more than one list of special orders per week, but I can only imagine they would not be too pleased about it. Now that I think about it, special orders are a hassle for me to handle. For example, I would need to compile the special order list and fax it multiple times per week if I ordered more than once per week. Then I would need to reconcile orders more than once a week, and I dread that process.

Q. Why do you fax orders to RAPA?

A. We’ve always done it that way. They told me once that special orders needed to be either faxed or phoned in.

Q. When did they tell you that?

A. I can’t recall exactly. I think it was in the late 1970s.

Q. We’ve looked at the shelf where you keep the special order items that have arrived. We were wondering what your method was for determining where a particular item would be placed on the shelf. Can you describe the thought process you go through?

A. Sure. Some parts are heavy. I want to place them neither too high nor too low. Otherwise, it hurts my back to take them off the shelf. I have one of my associates put them on the shelf, so that isn’t a problem. Besides that, I look for a place that will accommodate the particular size of package that the part comes in.

Q. How do you locate a particular item on the special order shelf when a customer comes to pick it up? We were expecting to see some sort of documentation on each item, like a tag or label, but we saw nothing.

A. I look through the items on the rack looking for the one with the matching part number.

Q. You said that you ordered, on average, approximately 10 special orders per week, but we saw about 30 order slips on the corkboard. Can you explain that?

A. Hmm … I never thought about that. I’m not sure, but it may have to do with the fact that some people take a while to come in and get their parts. Does that make sense?

Q. Does the RAPA distribution center need nearly an entire week to process special orders?

A. Of course. We have always done it this way. Distribution centers are very complex operations, and I wouldn’t even think of asking the RAPA people of doing this operation faster. I’m sure there is some reason why it takes them that long to process orders but, after all, I don’t know how distribution centers are run, so I wouldn’t want to be presumptuous and even ask them that question. Have you ever driven by the RAPA distribution center on Interstate 95? It’s a huge place, over 1 million square feet. It’s no wonder it takes a week.

Q. Have you ever received any complaints from customers about the special order process?

A. Only one that I can think of. Sometimes customers come in on the Thursday that I quote as the delivery date and ask for their part. Sometimes we have it, but we haven’t yet found the part and put it on the shelf with the customer’s name on it. In that case the customer needs to come back to the store again, and the second trip doesn’t make them happy, especially since the part was really in the store. Sometimes we haven’t actually received the part because the distribution center is out of stock and I wouldn’t be able to find it even if I took the time to look through the items on the pallet that comes in on Thursday.

Q. Does any part of this process annoy you in any way?

A. Well, some customers insist on calling to see if their part has arrived. These calls take at least 15 minutes, since we do not have a good way to easily identify whether the part has not been ordered, if it has been ordered and was out of stock at the distribution center, if it has been ordered and is on its way, or if it is in the store. The status of orders is tough to determine. Some customers call many times.