A Brief Introduction to Lean

Have you ever been frustrated because you needed to wait a long time for a good or service to be delivered to you? Do you sometimes feel that companies do not value your time and decrease your personal productivity because they cause you to wait idly while they take their time to serve you? Have you ever had experiences similar to any of the following?

- You arrived at the doctor’s office on time; you were even a few minutes early. Then, you waited in the waiting room, well past your appointment time, before being called into an examination room. Then, you waited again in the exam room until the doctor finally arrived.

- You ordered furniture, maybe a sofa or a chair from a company that makes furniture to order because they could not possibly stock all the upholstery and wood finish alternatives that they offer. Upon purchase, you were informed that delivery would be in 6 to 10 weeks. You were excited about getting the new furniture but were frustrated that you needed to wait so long before receiving it.

- You needed to order some equipment or repair parts for your company that were vitally needed to keep your operation moving. You waited a long time to receive the parts, and in the meantime, your operation’s performance suffered because you needed to implement workarounds like having employees work extra hours or produce goods of inferior quality.

- You traveled by air, your plane arrived at its destination, and the pilot taxied the plane to its gate. For 2½ hours, you looked at the Jetway as you waited for the ground personnel to move the Jetway up to the aircraft. You either missed your next flight or returned home later than otherwise necessary.

- You traveled by air and arrived at your destination on time, but your bags did not. You wondered how your bags could not have made your connection, which allowed for 2 hours between flights.

- You contacted a landscaping or construction company to discuss the possibility of undertaking a home improvement project but found that the contractor took a very long time to return your call. Perhaps your call was never returned. You found yourself wondering how you could trust a company to finish a job on time if they had difficulty simply returning your call.

You are the customer in all these situations, and you might well be upset and frustrated, possibly so much so that you would consider changing doctors, furniture companies, equipment suppliers, airlines, or contractors. The inability of the companies in the preceding examples to provide you with the goods and services you desire in a timely manner are due to these organizations’ inability to execute steps of a procedure in a timely manner. You may wait in the doctor’s office, for one of many reasons, because serving previous patients took a long time. You waited for your furniture because it takes the furniture manufacturer a long time to build the wood frame, apply finish, and then upholster it. Your order for equipment took a long time because it must be manufactured first or because the equipment distributor’s supply is slow or unreliable.

The purpose of the methodology called “Lean” is to remedy situations like these by reducing the time that it takes to provide customers with what they desire and, therefore, improve customers’ satisfaction with a company’s goods or services. One benefit, among many, of this improved satisfaction is continued and, perhaps, increased patronage from those who are served. We will give examples in chapter 2 of how making an effort to reduce lead time also improves business performance in other ways, including improved quality, less investment in inventory, less rework, and less warranty expense.

You might have noticed that the previous scenarios were written from the perspective of a customer, and similarly, many authors emphasize that the focus of Lean projects is to enhance customers’ experiences. We will see, however, that while many Lean projects have this external focus on the customers, Lean projects can be focused on providing internal benefit to the company by reducing cost, investment in inventory, and the cost of poor quality.

The History of Lean

Lean was first applied in manufacturing and was called “Lean Manufacturing,” but more recently, its principles are being applied in health care, administrative offices, food service, and other business contexts. To reflect its applicability to these other contexts, Lean Manufacturing is often referred to now as simply “Lean.” Arguably, Lean grew out of the Toyota Production System (TPS). TPS was developed in post–World War II Japan as the Toyoda family transitioned from manufacturing automatic looms to cars. A lack of resources in postwar Japan required lean operations with the minimum of parts inventory, factory, space, equipment, and labor. While the primary genesis of TPS was the need to maximize the production of automobiles with the minimum possible resources, TPS also contributed to Toyota’s continued quality improvement, which in turn led to the improved competitive position of Toyota vis-à-vis the former Big Three automakers of the United States.

Business Processes

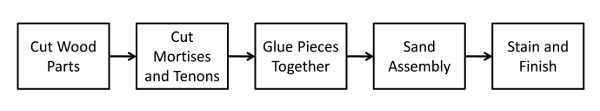

An essential concept that we will use in this book is that of a process. A process is a series of sequential steps that are executed in order to accomplish some goal. For example, if the goal is to build an end table, the steps employed in a furniture factory might be the following:

- Cut wood parts to appropriate length and width.

- Cut mortises and tenons in the wood parts that enable the parts to be joined.

- Glue pieces together.

- Sand assembled parts.

- Apply stain and finish.

It is frequently helpful to display a process graphically using rectangles to indicate each process step, as in Figure 1. This process can be associated with the pictorial representation of an end table in Figure 2.

Everything accomplished in business can be described as a process as we have done in Figure 1 for a furniture-manufacturing process. Whether you work in manufacturing, an administrative process (e.g., human resources, procurement, supplier management, business strategy, business development, accounting) or a service process (e.g., health care, food service, call center), what it takes to accomplish anything can be described as a series of steps, or a process. Processes are often more complex than the one in Figure 1 in the sense that they have many more steps, but we will postpone discussion of those situations until later in the book.

Figure 1. Process map for furniture manufacture.

Figure 2. End table construction.

Lean can be thought of as a set of tools to improve a process, where the type of improvement we will focus on is to reduce the elapsed time required to execute the process from start to finish, which is called process lead time. Thus Lean is a process improvement methodology. Other process improvement processes exist, most notably Six Sigma. In contrast to Lean, the primary goal of using Six Sigma is to improve quality, to reduce manufacturing defects, or to reduce service and administrative errors. Lean and Six Sigma are currently the two dominant process improvement methodologies, and they are often implemented simultaneously; when that is the case, the approach is called Lean Six Sigma.

Lean and Six Sigma can be further contrasted by comparing the tools used in each of these methodologies. Many of the tools used in Six Sigma rely on the application of statistics to processes to determine what defects are most important to address and what the root causes of the defects are and testing to see if a proposed remedy actually resolves the root causes. Learning the statistics can be difficult for many, and furthermore, collecting the data on which to use the statistical tools can be painstaking. In contrast, people who learn Lean find its tools almost without exception to be simple, intuitive, and easily learned. This is one argument for using Lean before Six Sigma: The tools are more easily learned and applied, thus accelerating the benefit achieved in improving business processes. Another argument for applying Lean first is that it generally results in a simpler process that is more readily evaluated with Six Sigma—indeed, many of the possible root causes of quality errors are likely to be resolved by streamlining the process with Lean before quality issues are explicitly addressed with Six Sigma. The more painstaking and time-consuming Six Sigma tools, then, do not have to be used to find more obvious root causes of defects that have already been sorted out.

While Lean will most frequently be the best set of tools to use first, the ultimate test is to determine which measure of performance is the most important to improve first. If quality improvement is the most important goal, then perhaps Six Sigma should be used first. Conversely, if reducing the time required to execute a process is most important (or one of the many accompanying benefits that we will discuss), then Lean should be used first. Which metrics are most important are determined at the outset of a project, and this is the first step in determining whether Lean or Six Sigma tools are most appropriate. Often, it is appropriate to apply tools from both Lean and Six Sigma. The bottom line is this: Use whatever tools are most appropriate. This book focuses on Lean, however, since it is frequently the methodology that gives the biggest process improvement bang for the buck—that is, the greatest benefit compared with the effort expended.

Returning to our discussion of Lean and TPS, one will find that virtually all of the tools associated with TPS are used in Lean. There is one tool used in Lean, however, that might never be observed in an application of TPS (at least this is the author’s experience). That tool is called value stream mapping, which we describe in chapter 2.

About This Book

This book is structured to succinctly describe how to apply the tools associated with Lean to improve business processes. It can be thought of as a quick-start manual that covers the essential tools, philosophies, and implementation strategies of Lean. The tools covered herein are those, in the author’s experience, most frequently applied and generally applicable to processes in all contexts. Descriptions of other, less frequently used tools can be found in the citations included in this book. There are many soft issues with implementing Lean, such as how to organize a company-wide effort, how to provide proper incentives, and how to build a culture conducive to Lean. Although this book addresses these important issues, more comprehensive coverage is available in other resources. This book contains all the philosophical underpinnings related to Lean in general and, in particular, to the tools that are described. Again, other books can be referenced to dive into these matters more thoroughly. In summary, this book has attempted to include the most vital information for a reader whose goal it is to effectively practice Lean as soon as possible. Including any additional materials, which would not likely be immediately needed, would have unnecessarily delayed the reader from getting started with Lean. Therefore, this book can be thought of as a lean presentation of Lean.

The main text in each chapter is presented as simply and clearly as possible to communicate the essence of Lean and its tools. The finer details of Lean that are necessary, but that might sidetrack a reader, are presented in sidebars throughout the book. A reader who ignores these frames upon the first reading will still be presented with a comprehensive description of the main concepts. The reader might, however, want to return to these finer points in subsequent passes through the material after he or she understands the basics and begins to apply Lean.

Readers will find that the techniques encompassed by Lean are very intuitive and quickly learned. However, as with any topic, the lessons of Lean cannot be fully absorbed until they are practiced. Therefore, practical exercises are included at the end of chapters that suggest how a reader can further his or her understanding by applying Lean in real settings. In addition, questions are provided in association with these exercises where appropriate to help readers reflect on their experience with the exercises to maximize the learning benefit. Spending some time quietly and thoughtfully entertaining these questions will greatly enhance the benefit of the exercises. Other exercises are also presented at the end of the chapters where concepts can be explored in the format of a typical homework problem.

This book can be used in many modes. It can be used as a self-study reference, or it can be used in a course. In either case, case studies are provided in the appendix of this book that offer the opportunity to exercise all the concepts in the book and might serve as a final examination in a course. Ideally, this book can be used as a text in a course where students are applying Lean in real companies while simultaneously studying this book and using it as a reference.

This book is divided into three parts. Part I, “Basics of Lean,” describes the motivation for why companies and organizations should want to do Lean, basic process analysis and mapping skills, and the discipline that a company must demonstrate in order to make Lean successful. Part II, “Lean Tools,” discusses tools used in Lean to improve processes. This part of the book does not contain an exhaustive reference to all tools used in Lean but, rather, the most frequently used tools in manufacturing, service, and administrative processes. Part III, “Implementing Lean,” discusses how to implement Lean, as well as some of the more frequently encountered roadblocks.