CHAPTER 8

USING PARADATA TO STUDY RESPONSE TO WITHIN-SURVEY REQUESTS

8.1 INTRODUCTION

Surveys have evolved significantly from the days where the sole means of data collection consisted of asking respondents to complete a standard Q&A-type questionnaire administered under a single mode of data collection. Although the traditional questionnaire remains the primary instrument for data collection in survey research, it is being supplemented with requests to collect additional data from respondents using less traditional methods. Such requests may include asking respondents for permission to collect physical or biological measurements (collectively referred to as “biomeasures”), access and link administrative records (e.g., Social Security, Medicare claims) to respondents’ survey information, switch from one mode of data collection (e.g., face to face, computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI)) to another mode (e.g., interactive voice response, web), complete and mail back a leave-behind questionnaire in a face-to-face interview, among other requests. Such requests, which are usually made within the survey interview itself, have spawned new scientific opportunities that allow researchers to answer important substantive and methodological questions that would be more difficult to answer otherwise.

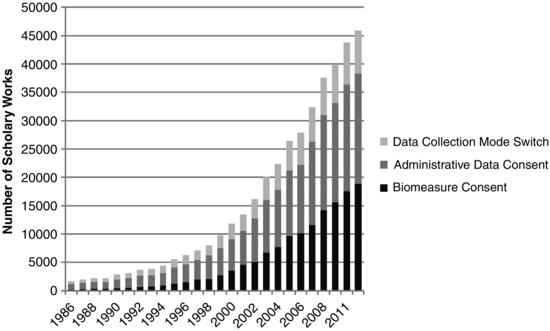

There is evidence that within-survey requests have been increasing. Figure 8.1 shows a steady rise in the annual number of scholarly works mentioning these requests based on a Google Scholar search. For example, for years 2000–2010, the number of works with reference to survey-based requests for consent to biomeasure collection increased about five fold, with approximately 3600 works in 2000 and 17,600 in 2010. The approximate growth in works with reference to requests for both record linkage consent and switching data collection modes was three fold. The figure suggests that the number of within-survey requests has been increasing, however, these trends should be interpreted with caution as it is not entirely clear how Google Scholar determines the relevancy of a scholar work. Furthermore, the actual number of scholarly works found may be overestimated due to the possibility of duplicates (which were not explicitly removed during the search) as well as the increasing availability of digital pieces over the reference period.

FIGURE 8.1 Number of scholarly works with reference to survey-based biomeasure consent, administrative data consent, and mode switch requests, by year (1986–2011). Results of a Google Scholar search of scholarly works with reference to survey-based requests for consent to collect biomeasures (Key Words: (survey OR questionnaire) AND (biospecimen OR biomarker OR gene OR genotype), link survey and administrative records (Key Words: (survey OR questionnaire) AND (administrative data) AND (consent)), and switch data collection modes (Key Words: (survey OR questionnaire) AND (data collection) AND (mode switch)).

As is true with any survey-based measurement, the failure of respondents to respond to a within-survey request can introduce an additional layer of nonresponse that threatens the quality of inferences obtained from the collected data and may lead to biased estimates. Paradata can be used to study nonresponse to within-survey requests and it is conceivable that such data could be used as a tool to facilitate the prediction, and possibly even the prevention, of its occurrence. This chapter highlights some of the most common within-survey requests and then reviews research in the field which has made use of paradata to study this form of nonresponse.

The failure to respond to within-survey requests is a nontrivial occurrence. For example, the rate of household survey respondents who provide consent to requests to link their survey information with their corresponding administrative records can vary substantially across studies and administrative data targets (see Sakshaug and Kreuter, 2012, for a list of studies and associated linkage consent rates). The rate of respondents who consent (or cooperate) with requests to collect biomeasures also exhibits significant variability depending on which type of measure is being collected, with the most intrusive measures (e.g., dried blood spots, vaginal swabs) yielding the lowest rates of cooperation (Jaszczak et al., 2009). Requests to switch respondents from an interviewer-administered mode of data collection (e.g., CATI) to a self-administered one (e.g., interactive voice response, web) midway through the interview can also incur nonresponse as a substantial portion of the sample (typically 20% or more) refuse to carry out the mode switch, or ostensibly agree to do so, but fail to resume the interview in the new mode (Tourangeau et al., 2002; Sakshaug and Kreuter, 2011). Other requests such as the completion and mail back of a leave-behind questionnaire in a face-to-face survey has been shown to be susceptible to nonresponse in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (Health and Retirement Study, 2004; Drum et al., 2009). Even more traditional within-surveys requests such as requests to answer detailed income items can be significantly affected by nonresponse. For example, the rate of nonresponse to income items typically lies between 20 and 40%, which is several times higher than the typical nonresponse rate for non-income items (Juster and Smith, 1997; Moore et al., 1999).

Because response to within-survey requests is not universal, there are concerns that the quality of inferences obtained from the resulting data may be poor due to (1) a further reduction in sample size (on top of unit nonresponse) and resulting increase in the sampling variability of the estimates and; (2) possible biases resulting from systematic differences between within-survey respondents and nonrespondents in terms of the variables being collected. Indeed, several studies have found significant differences between those who respond to within-survey requests and those who do not, as well as other indications of bias (Young et al., 2001; Jenkins et al., 2006; Sakshaug et al., 2010a, 2012). In light of the evidence, there have been several attempts to study and identify correlates of this form of nonresponse and understand underlying mechanisms that possibly explain its occurrence. Paradata, in particular, has been used to study respondents’ likelihood of response to several within-survey requests. Table 8.1 shows a list of studies that have used paradata to analyze respondents’ likelihood of completing various within-survey requests. The list is not exhaustive and is dominated by panel studies, but illustrates the many types of paradata that have been used to model respondents’ likelihood of response to collect biomeasures, link survey and administrative records, and switch data collection modes midway through the interview, among other requests.

Table 8.1 List of Selected Studies Using Paradata to Study Response to Within-Survey Requests

| Study | Type of Request | Paradata Used |

| Sakshaug et al. (2012) | Administrative data linkage consent | Interviewer observations; call record information; item missing data |

| Sakshaug and Kreuter (2011) | Data collection mode switch | Item missing data; time stamps; call record information |

| Sakshaug et al. (2010a) | Biomeasure consent | Interviewer observations; time stamps; call record information |

| Korbmacher and Schroeder (2012) | Administrative data linkage consent | Item missing data; interviewer rounding of biomeasure measurements |

| Health and Retirement Study (2004) | Mail back of leave-behind questionnaire | Call record information; interview language |

| Jenkins et al. (2006) | Administrative data linkage consent | Item missing data; call record information; time stamps; interviewer observations |

| Sala et al. (2012) | Administrative data linkage consent | Call record information; item missing data; interview information; prior wave information; interviewer information |

| Ofstedal et al. (2010) | Biomeasure consent | Call record information; interviewer information |

| Dahlhamer and Cox (2007) | Administrative data linkage consent | Item missing data; call record information; interviewer observations |

| Beste (2011) | Administrative data linkage consent | Item missing data; call record information; interviewer information |

Although there are many documented examples in the literature where paradata have been used to study unit nonresponse (Groves and Heeringa, 2006; Kreuter and Kohler, 2009; Kreuter et al., 2010), the notion of using paradata to study within-survey nonresponse is still a relatively new concept. The most common uses of paradata to address this form of nonresponse involve the creation of separate weighting adjustments. For example, the HRS implements a weighting adjustment methodology to adjust for the failure to collect biomeasures and leave-behind questionnaires from respondents (Health and Retirement Study, 2004). The adjustment models contain several covariates, including “resistance indicators” derived from call record information and prior-wave information, as well as substantive survey items, which are both shown to be predictive of within-survey response. Thus, complementing substantive variables with paradata appears to add additional information to the HRS adjustment model.

The creation of separate weighting adjustments for within-survey nonresponse can be useful for purposes of bias adjustment, but may result in increased variances of estimates, particularly in highly disproportional sample designs, designs in which the sample size is small, and when the association between the inclusion probabilities and the data is only weakly associated which is often the case in practice (Potter, 1990, 1993; Elliott, 2009). An alternative (or complementary), but less explored, use of paradata is to predict (or preidentify) respondents who are unlikely to complete a within-survey request and intervene on those respondents. To the extent that paradata are predictive of respondents’ willingness to complete a within-survey request, these data may be useful in terms of implementing intervention strategies that aim to increase the propensity that a respondent will complete said request.

The remainder of this chapter is organized around the types of within-survey requests that are increasingly being made within survey interviews. I give particular attention to the following requests: administrative data linkage consent, consent to biomeasure collection, data collection mode switch, and income item response. In each section, I provide a brief review of each type of request and summarize what is known about those who fail to take part. Then I give a more in-depth example of how paradata have been used to study response to each type of within-survey request. This is achieved by summarizing a published study from the literature for each of the first three requests (data linkage, biomeasures, and mode switch). For income item response, I present results from an unpublished analysis. Most of the presented examples are based on panel survey data, which tend to have more paradata at their disposal compared to cross-sectional surveys. Finally, I suggest possible uses of paradata for purposes of identifying potentially reluctant respondents and implementing intervention strategies aimed at reducing within-survey nonresponse.

8.2 CONSENT TO LINK SURVEY AND ADMINISTRATIVE RECORDS

Linking survey and administrative data sources can significantly enhance the quality and utility of the survey data and allows data users to answer important substantive and methodological questions that cannot be fully addressed using a single data source (Lillard and Farmer, 1997; Calderwood and Lessof, 2009). Examples of administrative databases commonly linked to survey data in the United States, Canada, and Europe, include Social Security records, tax and welfare benefit records, and health insurance and medical records. Due to the highly confidential and sensitive nature of these data sources, a necessary prerequisite to linking administrative data is obtaining informed consent from respondents. Informed consent is needed to ensure that respondents approve of the intended uses of their administrative data and are accepting of any potential risks (General Accounting Office, 2001).

Obtaining linkage consent from household survey respondents is not universal and there is significant variability in consent rates across surveys and administrative data targets (Sakshaug and Kreuter, 2012). As such, there are concerns regarding the quality of estimates obtained from linked survey and administrative databases. Studies have found significant differences between consenting and non-consenting respondents on many survey variables, including demographic (age, gender, race, education), earnings/wealth and benefit receipt, and health characteristics (Haider and Solon, 2000; Young et al., 2001; Banks et al., 2005; Jenkins et al., 2006; Dahlhamer and Cox, 2007; Sakshaug et al., 2012). To the extent that these survey variables are related to key administrative variables, inferences based on linked administrative data sources may be biased. However, it is often unclear whether non-consent biases exist for key administrative estimates, because the majority of linkage consent studies do not have access to administrative records for the non-consenting cases. One study, in particular, with administrative records available for both consenting and non-consenting cases, found small, but significant, non-consent biases for some substantive administrative data estimates (Sakshaug and Kreuter, 2012); thus, confirming the fact that non-consent biases can be present for estimates based on linked administrative data.

While the majority of factors found to be related to respondents’ likelihood of consent (e.g., demographics, income, health status) tend to be outside of the control of the survey designer, there have been some attempts to assess the impact of survey design features on consent. For example, in an experimental study of wording and placement of the consent question, Sakshaug et al. (2013) found that higher rates of linkage consent were obtained when the consent question was placed at the beginning of the questionnaire as opposed to the end. The effect of placement was stronger than the effect of wording as alternative wordings of the consent request did not significantly impact the consent rate. Clearly, there are many factors, within and outside the control of the survey designer, that seem to be related to respondents’ likelihood of linkage consent.

8.2.1 Modeling Linkage Consent Using Paradata: Example from the Health and Retirement Study

Sakshaug et al. (2012) utilized two sources of paradata to study linkage consent: interviewer observations and call record information. Both interviewer observations and call record information have been discussed extensively in the paradata literature, and the reader is referred to Kreuter and Olson (Chapter 2) for a detailed description of them.

In the HRS study, these paradata sources were used to study two hypothesized mechanisms of linkage consent: privacy/confidentiality concerns and general resistance toward the survey interview. Privacy and confidentiality concerns are often cited as reasons why many respondents are unwilling to provide linkage consent (Bates and Piani, 2005), but direct measurement of such concerns are usually not undertaken in surveys and observable expressions of concerns may not be seen until after consent has been requested. Predicting a causal relationship between privacy/confidentiality concerns and linkage consent can therefore be a difficult challenge.

The HRS collects a series of interviewer observations that are recorded for each respondent at the end of each interview. The following observations are collected with respect to having privacy and confidentiality concerns:

“During the interview, how often did the respondent ask you why you needed to know the answer to some questions? (never, seldom, or often)”

“During the interview, how often did the respondent express concern about whether his/her answers would be kept confidential? (never, seldom, or often)”

“How truthful do you believe the respondent was regarding his/her answers to financial questions? (completely truthful, mainly truthful, about half and half, mainly untruthful)”

These interviewer observations were recoded as binary variables indicating whether or not a respondent had expressed or indicated some level of concern (denoted by the underlined response options) and summed to form a “confidentiality concern” index. To address the problem of reverse-causality due to the fact that these observations are collected at the end of the interview (and after the linkage consent request), the index was formed using interviewer observations collected in the prior HRS wave (2006) and used to predict consent in the current wave (2008). Despite being approximately 2 years old, this paradata-derived index was found to be strongly predictive of the consent outcome as respondents who scored higher on the interviewer-assessed confidentiality concern index from 2006 were significantly less likely to give linkage consent in 2008. It should be noted that this relationship remained even after controlling for background, health, economic, and other substantive covariates, indicating the increased value of adding paradata to prediction models of consent.

To address the second hypothesized consent mechanism, that due to general interview resistance, the following interviewer observations were used as proxy indicators of respondent cooperativeness during the interview:

“During the interview, how often did the respondent ask how much longer the interview would last? (never, seldom, often)”

“How was respondent’s cooperation during the interview? (excellent, good, fair, poor)”

“How would you describe the level of resistance from the respondent? (low/passive, moderate, high)”

“How much did the respondent seem to enjoy the interview? (a great deal, quite a bit, some, a little, not at all)”

These interviewer observations, collected in the prior wave, were also recoded as binary variables (indicating whether or not respondents expressed some level of uncooperative behavior denoted by the underlined response options) and combined to form a single additive index. The paradata-based index was found to be highly predictive of respondents’ likelihood of consent in the final multivariate model. That is, respondents who scored higher on the index (less cooperative) were significantly less likely to give consent.

Paradata items based on call history information collected in the current wave were also used as proxy indicators of the general resistance hypothesis. These items included whether the respondent ever refused to take part in the interview (but later agreed to do so), the total number of call attempts needed to obtain a completed interview, whether the respondent was ever a nonrespondent in a prior wave of the HRS, and whether the respondent was reluctant to be interviewed in-person and opted for a telephone interview instead. Each of these items was found to be significantly predictive of linkage consent after simultaneously controlling for all other predictors.

8.2.2 Using Paradata for Intervention

Paradata are already used for the purpose of monitoring sample cases, informing interventions, and making design decisions that attempt to increase the likelihood of survey participation (see Kirgis and Lepkowski Chapter 6). Given that paradata, collected prior to the linkage consent request, can be predictive of the consent outcome, it is conceivable that such data could be used to preidentify respondents who are unlikely to give linkage consent during the survey interview. Identifying respondents who are potentially resistant to the linkage consent request may be useful for the purpose of modifying and/or adapting the request in such a way that attempts to increase their likelihood of consent. For example, paradata indicating privacy/confidentiality concerns may be used to flag cases that may require further justification regarding why the administrative data is being requested and more detailed descriptions of the safeguards put in place to keep the data anonymous and protect confidentiality.

For cases where paradata indicate general (non-confidentiality/privacy-related) resistance toward the interview (e.g., respondent indicates desire to finish interview more quickly, many call attempts needed to obtain a completed interview), the wording or placement of the consent request may be altered in such a way that addresses specific reasons of resistance. For example, respondents who express the desire to finish the interview more quickly, or require several call attempts, may be asked for linkage consent earlier in the interview when the consent decision may be less burdensome for respondents to consider, as opposed to the end of the interview when respondents may be in a less agreeable mood. The wording of the consent request may also be altered to highlight the fact that data linkage is a less burdensome method of data collection compared to self-report and that offering the option, in theory, motivates researchers to design a more parsimonious (shorter) questionnaire.

8.3 CONSENT TO COLLECT BIOMEASURES IN POPULATION-BASED SURVEYS

The collection of survey-based biomeasures, including biological materials (e.g., blood, urine), anthropometric measures (e.g., height/weight, waist circumference), physical performance assessments (e.g., grip strength, peak expiratory flow), and genetic measurements has had a significant impact on survey research and has led to breakthroughs in understanding how complex interactions between social, biological, and environmental factors can impact health outcomes (Finch et al., 2001; Weinstein et al., 2007). Weinstein and Willis (2001) describe several uses of survey-based biomeasures, including the ability to obtain population-representative data from nonclinical samples, calibrate self-reports with other measures of health and disease, explicate pathways and elaborate causal linkages between social environment and health, and link genetic markers with survey measures. Clearly, adding the collection of biomeasures to surveys provides the opportunity to address important research questions that surveys would not otherwise be equipped to answer.

Obtaining informed consent from survey respondents is necessary for the collection, analysis, and storage of survey-based biomeasures. The informed consent process is meant to provide respondents with a clear explanation of what biomeasures they will be asked to complete, how the collected measures will be used and stored, and any potential risks they face by participating (see Hauser et al., 2010, Chapter 4). Informed consent may be requested for each biomeasure separately (as is the case for the collection of blood and saliva in the HRS), or a single consent request may be made for all collected measures as is done for the medical examination component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Given the range of biomeasures that one can collect, it is not surprising that the consent (or cooperation) rates for each biomeasure can vary. The rates appear to be influenced by the sensitivity or invasiveness of the measure. For example, HRS reports consent rates of about 90–92% for anthropometric measurements (height/weight, waist circumference, etc.), about 83–84% from saliva, and about 80–87% from dried blood spots (Sakshaug et al., 2010a; Ofstedal et al., 2010). Cooperation rates are comparable in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), which reports rates of about 93–98% for anthropometric measures, about 90% for saliva, 85% for dried blood spots, and about 67% for self-administered vaginal swabs (Jaszczak et al., 2009). It is worth noting that both the HRS and NSHAP studies use field interviewers (as opposed to licensed medical personnel) to collect the biomeasures.

Despite high consent rates for some biomeasures, there is evidence that respondents who give consent are different than those who do not based on key variables. For example, in the HRS study, respondents who are older, Black, or who reside in urban locations are less likely to consent to all biomeasures compared to younger, non-Black, or rural-living respondents (Ofstedal et al., 2010; Sakshaug et al., 2010a). There is also some evidence that suggests that consent may be a function of health status: respondents who participate in fewer “mildly vigorous” activities consent at a lower rate than more active respondents (Sakshaug et al., 2010a). Furthermore, diabetics tend to consent to biomeasures, including collection of dried blood spots, at a higher rate than non-diabetics.

8.3.1 Modeling Biomeasure Consent Using Paradata: Example from the Health and Retirement Study

The study by Sakshaug et al. (2010a) used data from the 2006 HRS to analyze correlates of consent to the collection of anthropometric measurements, physical performance assessments, saliva, and dried blood spots. Several paradata items collected prior to the biomeasure consent request were used to predict consent, including interviewer observations, call record information, and time stamps.

Similar to the aforementioned administrative data linkage example, the interviewer observations included questions related to whether respondents asked how long the interview would last, whether they expressed concern regarding the confidentiality of their answers, and ratings of respondents’ level of cooperation and enjoyment during the interview (see Section 8.2.1 for the exact wording of the questions). These items were shown to be predictive of biomeasure consent; that is, respondents who expressed confidentiality concerns, asked how long the interview would last, and were observed to be at least somewhat uncooperative or did not appear to be enjoying the 2004 interview were less likely to give biomeasure consent in 2006. Contact history data were also used as proxy indicators of resistance; namely, the number of call attempts made to each responding case in the 2004 and 2006 waves of the HRS. The number of contact attempts in each wave (treated as separate covariates) were both negatively associated with consent in the 2006 wave. Overall, the interviewer observations and call record history data were strongly predictive of consent and together explained the majority of the variation in the consent model after controlling for respondent demographic and health characteristics, and interviewer attributes.

Another form of paradata, time stamps, were used to test the hypothesis that the amount of time elapsed prior to the consent request might influence whether respondents’ participate in biomeasure collection. Specifically, the hypothesis was that respondents with the most elapsed interview time prior to the biomeasure consent request would be less inclined to participate in biomeasure collection due to increased time burden. However, in this example, there was no clear relationship between elapsed time (categorized into quartiles) and consent.

8.3.2 Using Paradata for Intervention

Given that some forms of paradata collected prior to the collection of biomeasures are predictive of respondents’ likelihood of consent, it may be possible to use these data to inform intervention strategies that aim to increase consent rates. Just as paradata may be used to preidentify potential non-consenters to administrative data linkage (see Section 8.2.1), these data could be used to identify persons unlikely to consent to biomeasure collection. For example, hard-to-reach respondents and respondents who expressed some form of interview resistance in the prior wave interview (applicable only to panel surveys) may possess a lower likelihood of consent compared to other respondents and may require alternative strategies to increase their willingness. Alternative strategies for this particular group may include increasing the amount of monetary incentive that is often given to compensate respondents for the additional time they spend participating in biomarker collection. Other intervention approaches may involve more detailed justification on why biomeasures are being collected and the societal benefits of the research.

8.4 SWITCHING DATA COLLECTION MODES

It is well known that different modes of data collection possess different strengths and weaknesses. For example, interviewer-administered modes of data collection (e.g., face to face, telephone) are more costly but tend to yield higher response rates than self-administered modes (e.g., mail, web). On the other hand, self-administered modes tend to elicit more accurate survey reports about sensitive items than interviewer-administered modes (Tourangeau and Smith, 1998; Tourangeau et al., 2002; Kreuter et al., 2008). Given these competing strengths, it is often appropriate to mix modes, so that the strengths of one mode can offset the weaknesses of the other. For example, an interviewer-administered mode may be used to contact, recruit, and screen respondents before switching them to a self-administered mode where more sensitive items may be asked. This mixed-mode approach is particularly common in face-to-face surveys, including the National Survey of Family Growth, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. In CATI, a relatively common approach is to have interviewers contact, recruit, screen, and subsequently switch respondents to a self-administered mode, such as interactive voice response system (IVR) or an online questionnaire. Both computerized methods offer a higher degree of privacy relative to CATI alone and have been shown to lessen social desirability effects (Kreuter et al., 2008).

However, a significant disadvantage of the “recruit-and-switch” approach in CATI surveys is that a sizeable portion of the sample drops out during the mode switch. That is, sample members may superficially agree to complete the self-administered portion of the questionnaire, but either hang up during the transfer to the IVR system or fail to start the questionnaire in the online mode. Hang ups during IVR transfers are quite common (typically about 20–40%) and can be heightened by long transfer delays (Tourangeau et al., 2002; Couper et al., 2003). Failure to begin an online questionnaire after being switched from a CATI interview is also relatively common (Fricker et al., 2005; Kreuter et al., 2008).

The effects of mode switch nonresponse are nontrivial. It reduces the effective sample size and can introduce bias if respondents who carry out the switch are systematically different than those who do not. This bias has been experimentally shown to diminish, and, in some cases, offset the measurement error advantages of self-administration (Sakshaug et al., 2010b). That is, switching respondents from an interviewer-administered mode to a self-administered mode can yield estimates that contain more total bias (nonresponse and measurement error) than estimates based on respondents who are not switched to the self-administered mode.

Identifying characteristics of respondents who fail to comply with mode switch requests is an underdeveloped area of research. Because often very little information is collected from respondents prior to the mode switch, paradata and other sources of auxiliary data (e.g., administrative data) are potentially useful for studying this form of nonresponse.

8.4.1 Predicting Mode Switch Response Using Paradata: Example from a Survey of University Alumni

Using secondary data from a CATI survey of University of Maryland alumni, Sakshaug and Kreuter (2011) used paradata and administrative records to predict mode switch response. In the main study, alumni were contacted by telephone and administered a brief screening interview. Eligible respondents were then randomly assigned to one of three mode groups: IVR, Web, or continuation of interview in CATI. For the IVR group, interviewers transferred respondents to the computerized IVR system. For the Web group, an email containing instructions and a link to the online questionnaire were sent to each respondent. If the respondent did not provide an email address, the URL was read or faxed to them. About 22% of persons who agreed to take part in the IVR interview dropped out during the mode switch. The Web group experienced a higher dropout rate of about 42%. Nearly all persons assigned to the CATI interview completed the interview.

In addition to frame data, which consisted of a limited set of demographic variables, different forms of paradata were used as covariates in a model predicting mode switch response. The paradata consisted of contact records and information observed during the screening interview. The call record covariates included the log number of call attempts for each respondent and an indicator of whether or not they ever refused to participate. Neither of these covariates was found to be related to IVR or Web nonresponse.

Covariates derived from paradata collected during the screening interview included whether or not the respondent provided a substantive response to all screening questions (gender, year of birth, marital status, household size), whether an email address was provided for receipt of the questionnaire URL (web group only), and time stamp data indicating the amount of time that elapsed during the screening interview. The analytic model results indicated that screener item missing data was predictive of mode switch dropout for the web group, but not for the IVR group. That is, respondents who did not answer all of the screener questions, but ostensibly agreed to continue the interview, were less likely to login and begin the web survey. Whether or not an email address was provided during the screening interview by persons who were assigned to the web group was also predictive of mode switch response. Persons who did not provide an email address and opted to receive the URL verbally over the phone or by fax were less likely to login and begin the web survey. In general, these paradata covariates yielded higher correlations with the mode switch response outcome than the demographic frame covariates.

The amount of time that elapsed during the screening interview was hypothesized to have an influence on mode switch compliance. This covariate was recoded into quartiles to test whether persons who completed the screener interview at a relatively fast rate (first quartile) or relatively slow rate (fourth quartile) were more or less likely to complete the mode switch relative to persons falling within the middle range (second and third quartiles). However, the model indicated no support for this hypothesis as screener time was unrelated to mode switch response.

8.4.2 Using Paradata for Intervention

Given that respondents do not always carry out a mode switch request, it may be worthwhile for survey organizations to attempt to preidentify and intervene on persons unlikely to take part in the mode switch. For example, interviewers may be instructed to look for possible signs of resistance (e.g., item missing data) prior to the mode switch request. If such signs are observed, an intervention strategy may be implemented such as precluding the switch to a self-administered mode and resuming the interview in the initial interviewer-administered mode. Although the measurement advantages of self-administration would be lost, this approach would limit the potential loss of information and reduce the risk of nonresponse bias. In this study, nonresponse bias was a critical source of bias, which offset reductions in measurement error due to self-administration, and increased total error for some estimates (Sakshaug et al., 2010b). An alternative intervention strategy could consist of incentivizing persons flagged as likely mode switch nonrespondents similar to how unit nonresponders are often offered incentives during conversion attempts.

8.5 INCOME ITEM NONRESPONSE AND QUALITY OF INCOME REPORTS

Item nonresponse is a pervasive problem in surveys, especially with regard to income items. The typical rate of income item nonresponse is high in most surveys (typically between 20 and 40%) relative to non-income item nonresponse (typically between 1 and 5%) (Juster and Smith, 1997; Moore et al., 1999). There are indications in the literature that suggest that respondents who report their income are different from those who do not in terms of their actual income—with higher nonresponse among those with higher incomes (Greenless et al., 1982; Lillard et al., 1986; Riphahn and Serfling, 2005). Further, nonresponse to open-ended income items has decreased over time, but this decrease appears to be linked to trends in unit nonresponse (Yan et al., 2010). Moreover, Yan et al. (2010) found that refusal conversion rates were positively associated with income nonresponse, suggesting that respondents’ general willingness to participate in the survey has a strong impact on income item nonresponse.

Item nonresponse generally manifests itself in two ways: as a “don’t know” response or as a refusal. It is generally assumed that a “don’t know” response is given when a respondent lacks the adequate knowledge needed to answer the income question with the level of accuracy that is being requested, whereas a refusal is directly related to a respondent’s unwillingness to answer the item (Beatty and Herrmann, 2002). There are techniques that surveys employ that attempt to reduce the occurrence of both types of income item nonresponse and/or minimize their effects on data quality. For example, the “unfolding bracket” technique is commonly implemented in surveys and allows respondents to report their income as a range (between $20,000 and $30,000) rather than an actual amount. This technique has been shown to reduce income nonresponse by at least 50% in some studies (Heeringa et al., 1993; Juster and Smith, 1997; Battaglia et al., 2002).

Even when exact values to open-ended income questions are reported in the survey, they can suffer from accuracy problems. For example, respondents who are uncertain of their exact income value may significantly round their response. This rounding behavior may lead to “heaping” in the income distribution, which, in turn, may produce bias in nonlinear statistics like the median income value or poverty rate. Studies have shown that this phenomenon is common, especially for consumption, expenditure, and retrospective data (Browning et al., 2003; Pudney, 2008). This type of reporting error can be difficult to prevent at the time of data collection and is usually addressed during the analysis stage using statistical methods for measurement error adjustment (Heitjan and Rubin, 1990; el Messlaki et al., 2010; van der Laan and Kuijvenhoven, 2011).

8.5.1 Studying Income Item Nonresponse and Quality of Income Reports Using Paradata: Examples from the Health and Retirement Study

In this section, results from two separate analyses are presented. In the first analysis, panel data from the 2006 and 2008 waves of the HRS were used to study each component of income item nonresponse, “don’t knows” and refusals. The focus of this analysis is on the consistency of income item nonresponse by respondents over time and whether income nonresponse in the previous wave of a panel survey can predict income nonresponse in the current wave. Table 8.2 shows the percentage of item nonresponse in the 2008 HRS among item nonresponders in the 2006 HRS for several income-related items. In general, there is some consistency in item nonresponse between the two waves. About 20–40% of “don’t know” responses in the 2006 HRS were repeated as such by the same set of respondents in 2008, and about 40–50% of refusals in 2006 were repeated as such by the same respondents in 2008. Each result is statistically significant at the 0.001 level based on a chi-squared test of the two-way association of item nonresponse in both waves. The results suggest that there is some predictive power in using the 2006 item nonresponse indicators to predict item nonresponse in 2008, although the effect seems to be greater for item nonresponse due to refusals rather than for “don’t knows”.

Table 8.2 Percentage of Income Item Nonresponse in the 2008 HRS Conditional on Income Item Nonresponse in the 2006 HRS

| Income-Related Items in the 2006 and 2008 HRS | % (N) |

| Amount From Self-Employment Income | |

| Don’t know | 19.8 (24) |

| Refusal | 38.9 (42) |

| Amount from Wages and Salary | |

| Don’t know | 21.3 (65) |

| Refusal | 41.9 (90) |

| Amount from Social Security Income | |

| Don’t know | 37.1 (164) |

| Refusal | 50.4 (286) |

| Current Amount in Checking Account | |

| Don’t know | 28.5 (342) |

| Refusal | 43.6 (427) |

| Note: Estimates are based on persons designated as the “financial respondent” in the household. | |

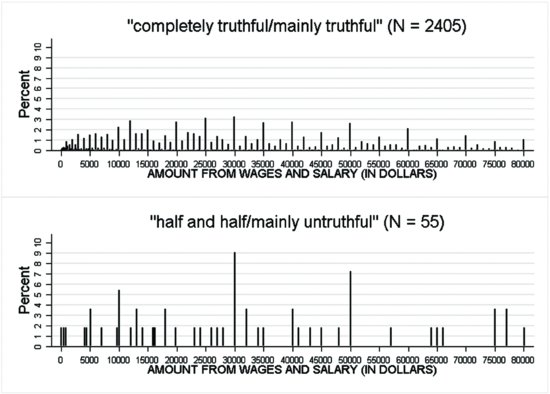

In the second analysis, panel data from the 2006 and 2008 HRS were again used. Here, paradata obtained from prior-wave (2006) interviewer observations are used to study the quality of income reports in the current (2008) wave, with a particular focus on income rounding and “heaping.” The interviewer observation of interest is a rating of how truthful each respondent was regarding his/her answers to financial questions in the interview (“How truthful do you believe the respondent was regarding his/her answers to financial questions?”). Figure 8.2 shows the relative frequencies of reported income amounts collected in the 2008 wave by interviewer truthfulness ratings collected in the 2006 wave. The top histogram shows the relative frequencies for respondents who were rated as being “completely truthful” or “mainly truthful” and the bottom histogram shows the group who were rated as being “half truthful and half untruthful” or “mainly untruthful” when answering financial questions.

FIGURE 8.2 Distribution of relative frequencies of reported amounts from wages and salary in the 2008 HRS by interviewer-observed ratings of respondent truthfulness to financial questions collected in the 2006 HRS.

The distribution shows that “heaping” is more common among the least “truthful” group, particularly for income values of $10,000, $30,000, and $50,000, which have relative frequencies about two to three times larger than those of the most “truthful” group. Despite the small sample size of the least truthful group, the results suggest that prior-wave paradata can potentially be useful in terms of identifying respondents whose income reports may be susceptible to heavy rounding error.

8.5.2 Using Paradata for Intervention

Based on the examples presented here, it is conceivable that paradata collected prior to the collection of income-related items could be used to inform intervention strategies that aim to reduce income item nonresponse and/or increase the quality of income reports. For example, panel survey respondents who answer “don’t know” to specific income items in a prior-wave interview may be flagged for a particular intervention such as the mailing of an advance letter stating that such questions will be asked again in the next wave and that respondents should review their financial records in advance of the interview. The same approach could be attempted for respondents who were observed by interviewers to be “less truthful” with regard to answering financial questions in a prior-wave interview, which may reduce the impact of rounding error. Furthermore, respondents who refused to report their open-ended income in the prior-wave interview may be flagged for conversion strategies (e.g., more detailed explanation on why income reports are needed for the study, the offering of an additional incentive, or starting the income questions with “unfolding brackets” rather than open-ended items).

8.6 SUMMARY

The failure to obtain responses to within-survey requests is a well-known problem in survey research. Various forms of paradata (e.g., interviewer observations, call record data, response behavior) collected prior to these requests have been linked to respondents’ likelihood of completing them. As such, I argue that paradata has the potential to be a useful tool for preidentifying and intervening on respondents who are less likely to complete within-survey requests. Preidentification of these respondents may be particularly useful in terms of implementing tailored intervention strategies that aim to boost response to these important requests. Identifying predictors of within-survey response that are easily visible to an interviewer or survey organization would seem to be most useful for preidentification of reluctant respondents and implementation of intervention strategies. These telltale signs could be used to flag potentially reluctant respondents in real-time with intervention strategies embedded into the survey instrument to facilitate a seamless implementation during the interview.

In conclusion, a list of key summary points is provided as general guidance to survey organizations interested in using paradata to study nonresponse to within-survey requests. The summary points are particular to panel surveys, but similar ideas may be adapted to pilot and cross-sectional studies:

- In a panel survey context, paradata collected from prior-wave interviews can be predictive of respondents’ likelihood of completing within-survey requests. This can be true even in cases where there is a large gap between interviews (e.g., 2 years).

- Collecting interviewer observations can be advantageous for purposes of predicting within-survey response. Observations that are indicative of respondents’ level of resistance toward the survey interview and are suggestive of particular reasons for resistance (e.g., confidentiality concerns) tend to be most predictive of within-survey response. Interviewer observations can also be useful for identifying respondents who may have a higher likelihood of making heavy rounding errors (or other misreporting errors) when answering income items.

- Call record data that is commonly collected in surveys (e.g., number of contact attempts, refusal history) can be useful predictors of respondent resistance to within-survey requests. Call record data collected from either prior-wave interviews or current-wave interviews both seem to be predictive of within-survey response.

- Prior-wave response behavior tends to be a decent predictor of future-wave response behavior with regard to income item nonresponse (due to refusal and “don’t know”). Utilizing prior-wave information on respondents’ income item response patterns could be used to inform intervention strategies that attempt to reduce and/or minimize the effects of income item nonresponse.

- Paradata appear to be well suited for predicting, preidentifying, and intervening on respondents who are unlikely to complete within-survey requests. To maximize this potential, survey organizations are advised to carry out pilot studies that make use of existing paradata (e.g., contact history data, prior response behavior) and newly collected paradata (e.g., interviewer observations, indicators of resistance) that can be incorporated into a prediction model (e.g., logit) and used to predict respondents’ likelihood of within-survey response in the main data collection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful for numerous discussions of this topic with Mick Couper, Frauke Kreuter, and with members of Frauke Kreuter’s research group in Munich. This work was partially funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

REFERENCES

Banks, J., Lessof, C., Taylor, R., Cox, K., and Philo, D. (2005). Linking Survey and Administrative Data in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Presented at the Meeting on Linking Survey and Administrative Data and Statistical Disclosure Control, Royal Statistical Society, London.

Bates, N. and Piani, A. (2005). Participation in the National Health Interview Survey: Exploring Reasons for Reluctance Using Contact History Process Data. In Proceedings of the Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology (FCSM) Research Conference.

Battaglia, M., Hoaglin, D., Izrael, D., Khare, M., and Mokdad, A. (2002). Improving Income Imputation by Using Partial Income Information and Ecological Variables. Proceedings of the ASA, Survey Research Methods Section, pages 152–157.

Beatty, P. and Herrmann, D. (2002). To Answer or Not to Answer: Decision Process Related to Survey Item Nonresponse. In Groves, R.M., Dillman, D.A., Eltinge, J.L., and Little, R.J.A., editors, Survey Nonresponse. Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Beste, J. (2011). Selektivitätsprozesse bei der Verknüpfung von Befragungs- mit Prozessdaten: Record Linkage mit Daten des Panels “Arbeitsmarkt und soziale Sicherung” und administrativen Daten der Bundesagentur für Arbeit. In Kreuter, F., Müller, G., and Trappmann, M., editors, FDZ-Methodenreport, Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung der Bundesagentur für Arbeit.

Browning, M., Crossley, T., and Weber, G. (2003). Asking Consumption Questions in General Purpose Surveys. Economic Journal, 113:F540–F567.

Calderwood, L. and Lessof, C. (2009). Enhancing Longitudinal Surveys by Linking to Administrative Data. In Lynn, P., editor, Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, pages 55–72. Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Couper, M., Singer, E., and Tourangeau, R. (2003). Understanding the Effects of Audio-CASI on Self-Reports of Sensitive Behavior. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67(3):385–395.

Dahlhamer, J.M. and Cox, C.S. (2007). Respondent Consent to Link Survey Data with Administrative Records: Results from a Split-Ballot Field Test with the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. In Proceedings of the Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology Research Conference.

Drum, M., Shiovitz-Ezra, S., Gaumer, E., and Lindau, S. (2009). Assessment of Smoking Behaviors and Alcohol Use in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64B:i119–i130.

el Messlaki, F., Kuijvenhoven, L., and Moerbeek, M. (2010). Making Use of Multiple Imputation to Analyze Heaped Data. Master’s thesis, Utrecht University.

Elliott, M. (2009). Model Averaging Methods for Weight Trimming in Generalized Linear Regression Models. Journal of Official Statistics, 25(1):1–20.

Finch, C., Vaupel, J., and Kinsella, K. (2001). Cells and Surveys. National Academies Press.

Fricker, S., Galesic, M., Tourangeau, R., and Yan, T. (2005). An Experimental Comparison of Web and Telephone Surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(3):370–392.

General Accounting Office (2001). Record Linkage and Privacy: Issues in Creating New Federal Research and Statistical Information. Report of the General Accounting Office, GAO-01-126SP.

Greenless, J., Reece, W., and Zieschang, K. (1982). Imputation of Missing Values When the Probability of Response Depends on the Variable Being Imputed. Journal of the ASA, 77(378):251–261.

Groves, R.M. and Heeringa, S.G. (2006). Responsive Design for Household Surveys: Tools for Actively Controlling Survey Nonresponse and Costs. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 169(3):439–457.

Haider, S. and Solon, S. (2000). Non Random Selection in the HRS Social Security Earnings Sample. Working Paper No. 00-01, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California.

Hauser, R., Weinstein, M., Pool, R., and Cohen, B. (2010). Conducting Biosocial Surveys: Collecting, Storing, Accessing, and Protecting Biospecimens and Biodata. National Academies Press.

Health and Retirement Study (2004). Sample Weights, Sample Selection Indicators and Response Rates for the Psychosocial and Disability Leave-Behind Questionnaires in HRS 2004. HRS Technical Report.

Heeringa, S., Hill, D.H., and Howell, D.A (1993). Unfolding Brackets for Reducing Item Nonresponse in Economic Surveys. AHEAD/HRS Report No. 94-029.

Heitjan, D. and Rubin, D. (1990). Inference from Coarse Data via Multiple Imputation with Application to Age Heaping. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 85(410):304–314.

Jaszczak, A., Lundeen, K., and Smith, S. (2009). Using Nonmedically Trained Interviewers to Collect Biomeasures in a National In-Home Survey. Field Methods, 21(1):26–48.

Jenkins, S.P., Cappellari, L., Lynn, P., Jäckle, A., and Sala, E. (2006). Patterns of Consent: Evidence from a General Household Survey. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 169(4):701–722.

Juster, T. and Smith, J. (1997). Improving the Quality of Economic Data: Lessons from the HRS and AHEAD. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92(440):1268–1278.

Korbmacher, J.M. and Schroeder, M. (2012). Consent when Linking Survey Data with Administrative Records: The Role of the Interviewer. Unpublished manuscript.

Kreuter, F. and Kohler, U. (2009). Analyzing Contact Sequences in Call Record Data. Potential and Limitations of Sequence Indicators for Nonresponse Adjustments in the European Social Survey. Journal of Official Statistics, 25(2):203–226.

Kreuter, F., Olson, K., Wagner, J., Yan, T., Ezzati-Rice, T., Casas-Cordero, C., Lemay, M., Peytchev, A., Groves, R., and Raghunathan, T. (2010). Using Proxy Measures and other Correlates of Survey Outcomes to Adjust for Non-response: Examples from Multiple Surveys. Journal of The Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 173(2):389–407.

Kreuter, F., Presser, S., and Tourangeau, R. (2008). Social Desirability Bias in CATI, IVR, and Web Surveys: The Effects of Mode and Question Sensitivity. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(5):874–865.

Lillard, L. and Farmer, M. (1997). Linking Medicare and National Survey Data. Annals of Internal Medicine, 127(8 Pt 2):691–695.

Lillard, L., Smith, J., and Welch, F. (1986). What Do We Really Know About Wages: The Importance of Nonreporting and Census Imputation. The Journal of Political Economy, 94(3):489–506.

Moore, J., Stinson, L., and Welniak, Jr., E. (1999). Income Reporting in Surveys: Cognitive Issues and Measurement Error. In Sirken, M.G., Herrmann, D.J., Schechter, S., Schwarz, N., Tanur, J.M., and Tourangeau, R., editors. Cognition and Survey Research, pages 155--173. New York: Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Ofstedal, M.B., Guyer, H., Sakshaug, J.W., and Couper, M.P. (2010). Changes in Biomarker Participation Rates in the HRS. Presented at the Panel Survey Methods Workshop, Mannheim, Germany, July.

Potter, F. (1990). A Study of Procedures to Identify and Trim Extreme Sampling Weights. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association, Section on Survey Research Methods, pages 225–230.

Potter, F. (1993). The Effect of Weight Trimming on Nonlinear Survey Estimates. Proceedings of the ASA, Section on Survey Research Methods, pages 758–763.

Pudney, S. (2008). Heaping and Leaping: Survey Response Behaviour and the Dynamics of Self-Reported Consumption Expenditure. ISER Working Paper Series 2008-09.

Riphahn, R. and Serfling, O. (2005). Item Nonresponse on Income and Wealth Questions. Empirical Economics, 30(2):521–538.

Sakshaug, J., Couper, M., and Ofstedal, M. (2010a). Characteristics of Physical Measurement Consent in a Population-Based Survey of Older Adults. Medical Care, 48(1):64–71.

Sakshaug, J. and Kreuter, F. (2011). Using Paradata and Other Auxiliary Data to Examine Mode Switch Nonresponse in a “Recruit-and-Switch” Telephone Survey. Journal of Official Statistics, 27(2):339–357.

Sakshaug, J. and Kreuter, F. (2012). Assessing the Magnitude of Non-Consent Biases in Linked Survey and Administrative Data. Survey Research Methods, 6(2):113–122.

Sakshaug, J.W., Couper, M.P., Ofstedal, M.B., and Weir, D. (2012). Linking Survey and Administrative Records: Mechanisms of Consent. Sociological Methods and Research, 41(4):535--569.

Sakshaug, J.W., Yan, T., and Tourangeau, R. (2010b). Nonresponse Error, Measurement Error, and Mode of Data Collection: Tradeoffs in a Multi-Mode Survey of Sensitive and Non-Sensitive Items. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(5):907–933.

Sakshaug, J.W., Tutz, V., and Kreuter, F. (2013). Placement, Wording, and Interviewers: Identifying Correlates of Consent to Link Survey and Administrative Data. Survey Research Methods. Forthcoming.

Sala, E., Burton, J., and Knies, G. (2012). Correlates of Obtaining Informed Consent: Respondents, Interview, and Interviewer Characteristics. Sociological Methods and Research, 41(3):414--439

Tourangeau, R. and Smith, T. (1998). Collecting Sensitive Information with Different Modes of Data Collection. In Couper, M.P., Baker, R., Bethlehem, J., Clark, C., Martin, J., Nicholls, W. and O'Reilly, J., editors. Computer Assisted Survey Information Collection, pages 431--454. Wiley and Sons, Inc. New York

Tourangeau, R., Steiger, D., and Wilson, D. (2002). Self-Administered Questions by Telephone: Evaluating Interactive Voice Response. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66(2):265–278.

van der Laan, J. and Kuijvenhoven, L. (2011). Imputation of Rounded Data. Discussion Paper 201108, Statistics Netherlands.

Weinstein, M., Vaupel, J., and Wachter, K. (2007). Biosocial Surveys. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

Weinstein, M. and Willis, R. (2001). Stretching Social Surveys to Include Bioindicators: Possibilities for the Health and Retirement Study, Experience from the Taiwan Study of the Elderly. In Finch, C.E., Vaupel, J.W. and Kinsella, K., editors. Cells and Surveys: Should Biological Measures be Included in Social Science Research?, pages 250--275. Committee on Population. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Yan, T., Curtin, R., and Jans, M. (2010). Trends in Income Nonresponse Over Two Decades. Journal of Official Statistics, 26(1):145–164.

Young, A.F., Dobson, A.J., and Byles, J.E. (2001). Health Services Research Using Linked Records: Who Consents and What is the Gain? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(5):417–420.