CHAPTER 1

The Core Concepts

PROJECTS ARE AN ESSENTIAL PART of human history. Some projects arise in myth, some in wartime, some from faith, and others from science and commerce. Some projects are monumental, and others are more modest. Ancient Egypt created the Great Pyramids, the Sphinx, the Library, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria. China’s Great Wall, which still stands today, took over 1,000 years to build. Peru’s Incan culture left us the lingering splendor of Machu Picchu. In our own time, we have placed men on the moon and returned them safely. We have developed drugs that target specific diseases. We have responded to environmental incidents, managed failures at nuclear sites, and responded to natural disasters. We have linked individuals and organizations through the miracle of the Internet. We have fulfilled the promise of integrated business systems that embrace enterprise resource planning, inventory management, production and control, human resources, and financial systems. This history of accomplishment will not end.

Some projects are ambitious and far-reaching in their social, economic, and political impacts. Others are less grand and more self-contained. Some require advances in basic science, and others deploy proven technology or best practices. Some projects challenge deeply held beliefs, and others uphold traditional values. And some projects fail.

The goal is always to achieve some beneficial change. Every project is an endeavor. Every project is an investment. Every project will end. Some will end when the goal is achieved, and others when the time or cost is disproportionate to the value. Some projects will be cancelled. In all cases, the project manager serves as the focal point of responsibility for the project’s time, cost, and scope.

Project Management Vocabulary

Success requires that the project manager serve as the focal point of effective, timely, and accurate communication. To do this well, the project manager must master a new vocabulary and must use it consistently to communicate successfully. The definitions introduced in this chapter are the project manager’s methods of art—words and terms used in the context of planning, scheduling, and controlling projects.

A project is “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.”* Projects are temporary because they have a definite beginning and a definite end. They are unique because the product, service, or result is different in some distinguishing way from similar products, services, or results. The construction of a headquarters building for ABC Industries is an example of a project. The unique work is defined by the building plans and has a specific beginning and end.

Project management is “the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements” (Ibid., p. 6).

In mature organizations, multiple projects may be grouped and managed together in a program to obtain benefits and control not available from managing them individually (see Ibid., p. 9). Multiple programs may be grouped and prioritized into portfolios aligned around larger strategic organizational objectives. Portfolio management is the “centralized management of one or more portfolios, which includes identifying, prioritizing, authorizing, managing, and controlling projects, programs, and other related work, to achieve specific strategic business objectives” (Ibid., p. 9).

Why Project Management?

Project management stems from the need to plan and coordinate large, complex, multifunctional efforts. History provides us with many project examples. Noah’s project was straightforward—build an ark. The material requirements indicated that the ark should be built with gopher wood and to prescribed dimensions. Ulysses built the Trojan horse. Medieval cathedrals were designed and built over the course of centuries. However, not one of these projects deployed a consistent, coherent methodology of management techniques aimed at schedule development, cost control, resource acquisition and deployment, and risk management.

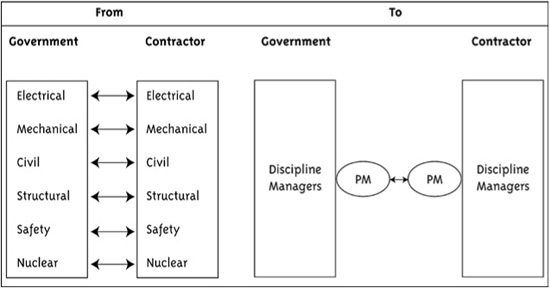

Project management, as we have come to know it, was the solution to a practical problem. Governmental communications in the latter part of the twentieth century, unfortunately, often involved technical staff speaking only with their technical counterparts in defense-contractor organizations. Each discipline conferred with its own colleagues. Changes in one aspect of a system—say, payload weight—were not always communicated to other interested and affected parties, such as avionics or engine design. Too often, the results were cost and schedule overruns, as well as systems that failed to meet expectations.

The concept of the project manager emerged as a focal point of integration for time, cost, and product quality (see Figure 1-1). This need for a central point of integration was also apparent in many other types of projects. Architectural, engineering, and construction projects were a logical place to use project management techniques. Information systems design and development efforts also were likely candidates to benefit from project management. For projects addressing basic or pure research, principal investigators were no longer only the best scientists, but were also expected to manage the undertaking to one degree or another.

Figure 1-1 Evolution of Project Management.

If project management is indeed a solution, then we have to recognize how it reacts and adapts to workplace and marketplace needs such as the following:

![]() Higher-quality products

Higher-quality products

![]() More customized products

More customized products

![]() Shorter time-to-market

Shorter time-to-market

![]() Global competition

Global competition

![]() Easier information access

Easier information access

![]() Technology growth

Technology growth

![]() Global organizations seeking uniform practices

Global organizations seeking uniform practices

Classic Functions of Project Management

Management is routinely understood to be accomplishing work through the expenditure of resources. More rigorously, management is the science of employing resources efficiently in the accomplishment of a goal. The classic functions of management are planning, directing, organizing, staffing, controlling, and coordinating.

Planning

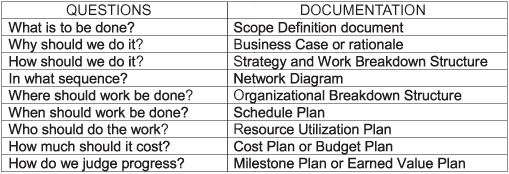

Planning is a process. It begins with an understanding of the current situation (the “as-is” state) and the desired future (the “to-be” state). The gap between these two states causes the project manager to identify and evaluate alternative approaches, recommend a preferred course of action, and then synthesize that course of action into a viable plan. Planning raises and answers the questions shown in Figure 1-2.

Directing

Directing communicates the goals, purposes, procedures, and means to those who will do the work. Directing is the process of communicating the plan, whether orally or in writing.

Figure 1-2 Planning Questions.

Organizing

Organizing brings together the nonhuman resources needed to achieve the project’s objectives. To organize is to manage the procurement life cycle. It begins with the need to define requirements for materials, equipment, space, and supplies. It also identifies sources of supply, ordering, reception, storage, distribution, security, and disposal activities.

Staffing

Staffing brings together the human resources. From a managerial perspective, human resources are first seen as the number and mix of individuals in terms of skills, competency levels, physical and logical location, and costs per unit of time.

Controlling

Controlling is the process of measuring progress toward an objective, evaluating what remains to be done, and taking the necessary corrective action to achieve the objectives. In project management terms, it involves determining variances from the approved plan, then taking action to correct those variances.

Coordinating

Coordinating is the act of synchronizing activities to ensure they are carried out in relation to their importance and with a minimum of conflict. When two or more entities compete for the same resource—time, space, money, or people—there is a need for coordination. The primary mechanism of coordination is prioritization.

Processes in the Life of a Project

The Project Management Institute, an organization dedicated to advocating the project management profession, has produced a valuable document called A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). This publication provides a broad view of what project management professionals should know and what they do in performing their work. This guide identifies and describes the body of knowledge that is generally accepted, provides common project management terminology and standards, and acts as a basic reference for anyone interested in the profession of project management.

The PMBOK® Guide groups project management processes into five categories:

1. Initiating: Defining and authorizing the project

2. Planning: Establishing the project scope, refining the objectives, and defining the course of action to attain the objectives

3. Executing: Integrating people and other resources to carry out the work defined in the project plan

4. Monitoring and Controlling: Tracking, reviewing, and regulating the progress and performance of the project plan, identifying where changes to the plan are required, and taking corrective action

5. Closing: Finalizing all activities across all the process groups to formally close the project

Each of these groups has a number of interrelated processes that must be carried out for the success of a project.

Knowledge Areas

The PMBOK® Guide also identifies nine areas that describe the knowledge and practice of project management:

1. Integration Management. Identifying, defining, combining, unifying, and coordinating the various processes and project management activities within the project management process groups. It includes developing the project charter and plan, directing and managing the project execution, monitoring and controlling project work, controlling change, and closing the project.

2. Scope Management. Ensuring that the project includes all the work required, and only the work required, to complete the project successfully. It includes collecting requirements, defining scope, creating a work breakdown structure, verifying scope, and controlling scope.

3. Time Management. Managing timely completion of the project. It consists of defining activities, sequencing activities, estimating activity resources, estimating activity durations, developing schedules, and controlling schedules.

4. Cost Management. Estimating, budgeting, and controlling costs to complete the project within the approved budget. It includes estimating costs, determining budgets, and controlling costs.

5. Quality Management. Determining quality policies, objectives, and responsibilities so that the project will satisfy the needs for which it was undertaken. It consists of planning quality, performing quality assurance, and performing quality control.

6. Human Resources Management. Organizing, managing, and leading the project team. It includes developing human resources plans and acquiring, developing, and managing project teams.

7. Communications Management. Ensuring timely and appropriate project information, including its generation, collection, distribution, storage, retrieval, and ultimate disposition. It consists of identifying stakeholders, planning communications, distributing information, managing stakeholder expectations, and reporting performance.

8. Risk Management. Conducting risk management planning, identification, analysis, response planning, and monitoring and control on a project. It includes planning risk management, identifying risks, performing qualitative risk analysis, performing quantitative risk analysis, planning risk responses, and monitoring and controlling risks.

9. Procurement Management. Purchasing or acquiring products, services, or results needed from outside the project team. It consists of planning procurements, conducting procurements, administering procurements, and closing procurements.