CHAPTER 3

Collecting Requirements and Defining Scope

COLLECTING REQUIREMENTS AND DEFINING your project’s scope are critical to planning a successful project. The PMBOK® Guide offers two related definitions for scope. Project scope includes “the work that needs to be accomplished to deliver a product, service, or result with the specified features and functions.” Because projects often create products, you may also have to define the scope of a product. Product scope includes “the features and functions that characterize a product, service, or result.”*

Clearly defining a project’s scope is not merely good theory and common sense. Project schedules and budgets overrun when the scope is unclear and when the scope is not aligned with enterprise goals, core values, structure, strategy, staff, and systems. Studies show that projects that spend more time in planning and design have fewer overruns.

The Five Processes of Project Scope Management

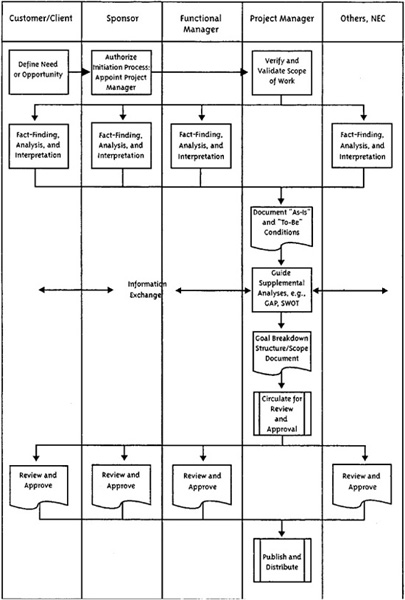

The processes for collecting requirements and defining scope may be simple or complex, trivial or traumatic. In all cases, it is best done by the project team, with the sustained participation of all interested and affected parties. Figure 3-1 suggests a high-level approach to scope definition.

Project scope management includes five processes, the first two of which will be discussed in this chapter, and the last three will be discussed in Chapter 4:

1. Collecting requirements includes the processes for identifying and documenting features and functions of the end result of the project (the product, service, or result).

2. Creating a scope statement formally documents what the project will and will not produce.

3. Creating a work breakdown structure (WBS) creates a hierarchical breakdown of activities and end products, which organizes and defines all the work to be completed in a project.

4. Verifying scope achieves formal acceptance of the project scope.

5. Controlling scope creates a change control system to manage the project scope.

Collecting Requirements

This step includes the processes for identifying and documenting the features and functions of the end result of the project (the product, service, or result). There are several methods you can use to collect project requirements. The methods described in this section are not exhaustive and should be tailored for each project and its unique context.

Figure 3-1 Scope Definition Process.

Interviews

Interviews are the most traditional means of collecting requirements. Interviews may be informal or formal and are tailored to each type of stakeholder. Interviewing techniques are discussed in Chapter 12, “Leading and Directing Project Teams.”

Focus Groups

Conducting a focus group is a form of research in which the members of a group are asked about their knowledge of or attitude toward a product or service. Questions are asked in an interactive group setting where participants are free to talk with other group members.

Expert Judgment

Expert judgment is a technique that relies on the experience of others. It involves consulting with experts who, based on their history of working on similar projects, know and understand the project and its application. Although it is often used, expert judgment may be biased.

Gap Analysis

Gap analysis is routinely used for business-process reengineering, quality improvement, industry certification, cost reduction, and efficiency-improvement projects. This approach is also helpful in collecting requirements because it highlights the difference between the current state and the desired state. The following is an example of a gap analysis on the project of hosting a dinner party:

Step one: Determine the desired status. The desired outcome is that the necessary food, condiments, and supplies are available in sufficient quantity, quality, and time for the event. Special attention should be paid to dietary needs based on religion, tradition, or health needs of your guests.

Step two: Determine the current status. The current situation is found by taking inventory of pantries, refrigerators, and freezers.

Step three: Determine the difference between the two. In essence, subtract the as-is list from the to-be list.

Step four: Develop a strategy to fill the gap. The difference is your shopping list.

Walk-Throughs

The project team can conduct a walk-through or site inspection of the client’s processes in order to understand the business process and to document data flow, materials, supplies, and correspondence. This is helpful when the project involves replacing a process, usually through automation, and for process improvement. A walk-through is particularly helpful when it can be combined with operations data, such as that of dealing with complaints, response times, and rejects.

Creativity Tools

There are many creativity tools that can assist in collecting requirements. Brainstorming is a technique used for problems that resist traditional forms of analysis. The goal of a brainstorming session is to stimulate the generation of ideas and then check them for potential use. The key characteristic of a brainstorming session is that there are no wrong answers. An affinity diagram can then be used to refine the results of the brainstorm by organizing the ideas into related groups.

Mind mapping is a tool for processing information in both serial and associative forms. One begins with a central idea and then asks teammates to identify and list whatever comes to mind, periodically regrouping the ideas under headings that seem natural and appropriate.

Other Tools

There are many other tools and methodologies that can help you collect requirements. These include flowcharts, process reviews, data reviews (such as financial, operational, and managerial audits), models, simulations, competitive intelligence, focus groups, and literature searches.

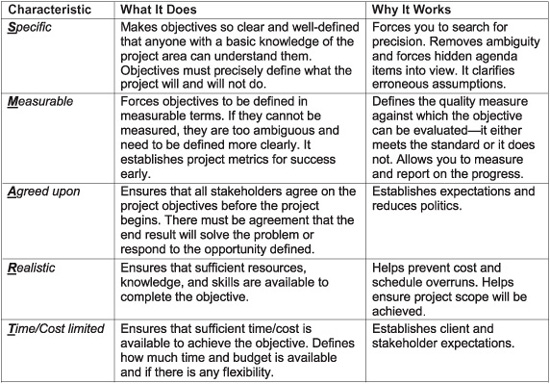

SMART Requirements

One important aspect of establishing client and stakeholder expectations takes into account the difference between well-defined requirements and poorly defined ones. Although several models exist, one of them asks if the project requirements meet the SMART test, that is, whether they are Specific, Measurable, Agreed upon, Realistic, and Time/Cost limited. The SMART model is designed to minimize misinterpretation or vague assumptions. Figure 3-2 lists the characteristics of SMART objectives and provides a brief description of their implementation.

Fuzzy Requirements

Frequently, the project manager will be faced with the situation that a client cannot or does not fully understand what he or she wants. A similar issue exists when a client and internal stakeholders are in conflict regarding the project requirements. These situations create what are known as fuzzy requirements—those that are not specific, measurable, agreed upon, realistic, or time/cost limited.

Frequently, clients and project managers create fuzzy requirements because of misunderstandings. Clients may not understand the technology, or project teams may not understand the clients’ needs. The following represent several helpful techniques:

![]() Define terms or use different terms to reach understanding and agreement.

Define terms or use different terms to reach understanding and agreement.

![]() Concentrate on outcomes or desired results, not on process variables.

Concentrate on outcomes or desired results, not on process variables.

![]() Build prototypes.

Build prototypes.

![]() Use acronyms sparingly.

Use acronyms sparingly.

![]() Avoid needless technical jargon.

Avoid needless technical jargon.

![]() Reflect on and revisit what you have heard.

Reflect on and revisit what you have heard.

![]() Use physical demonstrations or experiments.

Use physical demonstrations or experiments.

![]() Document your agreements early and often.

Document your agreements early and often.

![]() Use idea-generating techniques like brainstorming and mind mapping.

Use idea-generating techniques like brainstorming and mind mapping.

Creating a Scope Statement

The scope statement formally documents what the project will and will not produce. It defines your project, including objectives, specifications, exclusions, constraints, risks, and assumptions.

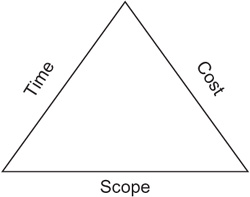

Objectives: Time, Cost, Scope

Projects are defined and managed within the triple constraints (or expectations) of time, cost, and scope. These objectives are commonly referred to as the project triangle, which is depicted in Figure 3-3.

The time constraint is defined in the project’s schedule. The ceiling on cost expenditures is the project budget. The budget itself is a scorekeeping tool that measures the anticipated rate and timing of expenditures for the labor costs, equipment, material, travel, and other items needed to meet project objectives. And, finally, the project scope includes the predefined technical and performance targets. The challenge of the project manager is to keep all sides of the project triangle balanced. If the triangle is not balanced, the project will fail along one of the three sides. For example, if you start with a “balanced” triangle and then receive a request for additional features from your customer (an increase in scope), you must make an adjustment in the time and/or cost. Otherwise, you simply won’t be able to accomplish the increased amount of work in the time and within the budget previously defined. This concept also highlights the importance of clearly and completely defining project requirements during project planning.

Figure 3-3 The Project Triangle.

In prioritizing the project objectives, it is critical to recognize what drives the project. Some projects are driven by schedule. This means that a completion date is fixed and the other sides of the project triangle (cost and scope) can to some degree be negotiated. In other projects, the most important drivers are budget or scope. The following are reasons to understand what drives the project:

![]() Project drivers influence all dimensions of project planning.

Project drivers influence all dimensions of project planning.

![]() Project drivers help guide your selection of corrective actions.

Project drivers help guide your selection of corrective actions.

![]() Project drivers assist you in controlling proposed changes to project scope, schedule, or cost.

Project drivers assist you in controlling proposed changes to project scope, schedule, or cost.

![]() Project drivers help create appropriate management reserves and contingencies.

Project drivers help create appropriate management reserves and contingencies.

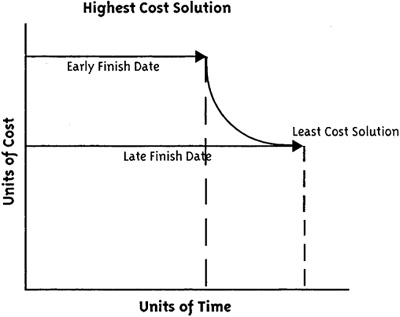

The scope document should address the trade-offs among time, cost, and scope. Conventional wisdom says: “You may want it good, fast, and cheap. Pick two!” Underlying this aphorism is an intuitive grasp of simple points:

![]() If the technical requirements of a project are fixed, then compressing the project schedule will probably increase project costs.

If the technical requirements of a project are fixed, then compressing the project schedule will probably increase project costs.

![]() The more the schedule is compressed, the greater the rate of increase in cost per unit of time.

The more the schedule is compressed, the greater the rate of increase in cost per unit of time.

![]() If you add requirements to the scope, then either time or cost (or both!) will increase.

If you add requirements to the scope, then either time or cost (or both!) will increase.

![]() If the project budget is fixed (as by legislative appropriation or a fixed-price contract), then negotiation arises on the other two sides of the project triangle (time and scope).

If the project budget is fixed (as by legislative appropriation or a fixed-price contract), then negotiation arises on the other two sides of the project triangle (time and scope).

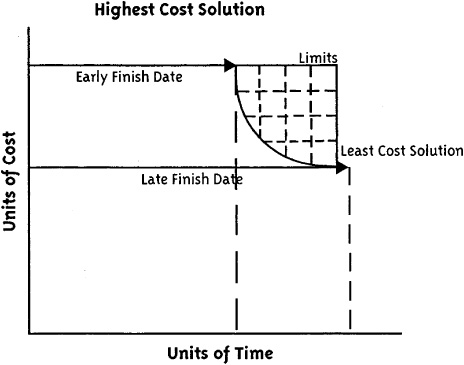

Visualizing these relationships is straightforward and shown in Figure 3-4. The graph shows the range of cost-versus-time solutions for a given project scope. For any project, there are three critical data points:

1. The earliest finish date of the last activity

2. The latest allowable finish date of the last activity

3. The least cost to accomplish all the work required

By extension, we can find a point that describes the late finish and last dollar. This point is the sponsor’s expectation that she or he will receive the final product or service on or before a given date and at a cost not to exceed some predefined amount. The area between any point on the time/cost trade-off line and the outer limits of the project is a management reserve or contingency for the project manager. Now the drawing looks like that shown in Figure 3-5.

Figure 3-4 Visualizing a Time/Cost Trade-Off.

The project manager can now present the options to senior management and other stakeholders. Problems will arise only when the project budget is less than the cheapest solution or the needed delivery date is sooner than the fastest solution.

Specifications

Specifications, by definition, are unique for each project. Nevertheless, they must also conform to applicable laws, standards, codes, and conventions, which may derive from sources such as the following:

Figure 3-5 Project Limits and Contingency.

![]() Government agencies may be international, national, state, or local agencies involved in regulating specific industries, the environment, health, safety, or transportation. Some agencies regulate standards, licensing, or zoning.

Government agencies may be international, national, state, or local agencies involved in regulating specific industries, the environment, health, safety, or transportation. Some agencies regulate standards, licensing, or zoning.

![]() Industry-specific professional or trade associations may develop codes, conventions, or standard practices. These associations and practices include the International Organization for Standardization (ISO); the American National Standards Institute (ANSI); Underwriters Laboratories, Inc. (UL listing); Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP); Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS); the Software Engineering Institute (SEI); and the Project Management Institute (PMI).

Industry-specific professional or trade associations may develop codes, conventions, or standard practices. These associations and practices include the International Organization for Standardization (ISO); the American National Standards Institute (ANSI); Underwriters Laboratories, Inc. (UL listing); Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP); Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (GAAS); the Software Engineering Institute (SEI); and the Project Management Institute (PMI).

![]() Your own organization may have standards for data names and uses, numbering schemes for engineering drawings, or a visual identity program to guide the use of the company logo.

Your own organization may have standards for data names and uses, numbering schemes for engineering drawings, or a visual identity program to guide the use of the company logo.

![]() Your customers, clients, or end users may impose their standards on your work. For example, “The contractor shall prepare and submit all engineering drawings as [name of product] files.” The standards that apply to your project should be developed early in the development of specifications. They should be articulated by subject matter experts, embedded in the scope document, and used later on to judge the quality of intermediate and final deliverables.

Your customers, clients, or end users may impose their standards on your work. For example, “The contractor shall prepare and submit all engineering drawings as [name of product] files.” The standards that apply to your project should be developed early in the development of specifications. They should be articulated by subject matter experts, embedded in the scope document, and used later on to judge the quality of intermediate and final deliverables.

Exclusions

An adequate scope document defines not only what the project includes; it also establishes project exclusions. This delineation, although seldom perfect, forces stakeholders to confer openly and candidly in the early stages of a project. The project manager guides this dialogue. Its product is a scope definition with clear boundaries, diminished uncertainty, and minimal likelihood that the project manager will hear (at the end of the assignment), “I know it’s what I said, but it’s not what I want.”

Scope exclusions define items that may be closely related to the project’s goal but are not to be included in this phase, stage, or release. Exclusions may extend to piece parts, specific features and functions, materials, and performance measures. The important issue is that these exclusions be identified early, debated openly, and resolved with finality.

Constraints

Constraints are items that limit the project manager’s degree of freedom when planning, scheduling, and controlling project work. Often, these constraints are administrative, financial, or procedural in nature. The following are examples of constraints:

![]() There is a hiring freeze for specific positions.

There is a hiring freeze for specific positions.

![]() The project has a capital equipment ceiling of $500,000.

The project has a capital equipment ceiling of $500,000.

![]() The team must use an executive’s brother-in-law as the architect.

The team must use an executive’s brother-in-law as the architect.

![]() A vice president must approve all travel.

A vice president must approve all travel.

Risks

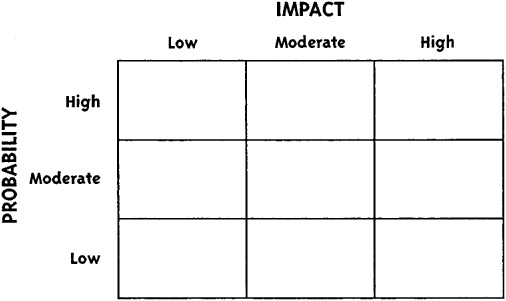

Risks are uncertain events that may affect the project for better or worse. These events may be categorized in various ways, but their central theme is that one cannot predict with certainty the source, timing, impact, or significance of specific risks. Therefore, at the start of a project, it makes sense to undertake a high-level risk assessment by identifying the sources and types of uncertainty.

The initial assessment of risks to the project involves three steps:

1. Identify the risks likely to impede project progress and success.

2. Rank each risk in terms of the likelihood of occurrence and the impact on the project if the risk occurs. Figure 3-6 illustrates a simple and convenient way to present the results of this initial, high-level risk analysis.

3. Develop an initial list of responses for the risk that have unacceptable outcomes.

Figure 3-6 Risk Probability and Impact.

Assumptions

Assumptions are made to fill in gaps of credible knowledge, to simplify complex realities, and to get others to react. One way to categorize assumptions is to group them under one of four headings:

1. Technical and scientific assumptions routinely deal with hardware, software, or related configuration issues. We can postulate change or stability. In designing an experiment, we might assume that ten tests will be required or that a certain number of patients must be enrolled to achieve some level of confidence in results.

2. Organizational and administrative assumptions typically deal with roles and responsibilities, issues of outsourcing versus internal development, or make-or-buy decisions. By extension, they may address applicable standards for documentation or the tenure of project staff at the end of the project.

3. Resource and asset availability assumptions address issues regarding whether adequate numbers of people, materials, supplies, space, and equipment are available to meet project requirements. This set of assumptions requires the project manager to revisit some of the organizational assumptions just noted.

4. Macro-level assumptions are those that are so profound or pervasive that project managers cannot negotiate them in any meaningful way. We could include here issues of currency fluctuations, exchange rates, public policy, population migrations, and related demographic trends.

Example Scope Document

This chapter concludes with an example that consolidates the key themes and serves as a working model of a high-level scope document (and the thinking process that underlies its development). The example used here is simple and specific. It is not intended to show all possible scenarios, but it does provide a concrete example of how to develop a scope document. It captures the way a project manager thinks.

The case example begins when you receive the following e-mail from your supervisor, the business-unit manager of the bridge-building company where you are an experienced project manager:

To: D. Smith

From: S. Darby

Re: New Bridge Project

I have another bridge project for you. Our biggest client, Glenfracas Distilleries, wants to move its product over land into a new market at the rate of 100,000 liters per week using its own ten-ton trucks. The River Why stands in the way. The company is already prepared to spend mid–seven figures, and our signed contract is for a cost-plus-percentage fee. The client’s major competitor plans to have product in the same market within three months. Take this ball and run with it. We can discuss your understanding of the project scope when I call you from Cancun tomorrow.

Although you may rather be in Cancun to discuss this project with the boss in person, it is time to ask some questions:

![]() What is the client’s goal? Move product by road. So what? The River Why stands in the way.

What is the client’s goal? Move product by road. So what? The River Why stands in the way.

![]() What is the boss’s goal? Make money. Keep our biggest client happy. So what? At least he has signed a contract, but mid-seven might not be enough money unless we keep the costs down.

What is the boss’s goal? Make money. Keep our biggest client happy. So what? At least he has signed a contract, but mid-seven might not be enough money unless we keep the costs down.

![]() How does the client describe the finished product? He doesn’t … at least not yet. So what? Maybe I can make some assumptions: If a ten-ton truck carries ten tons, and one ton of product is approximately nine hundred liters, that means that the bridge has to be available for only eleven loaded trucks each week. So what? Maybe this bridge has to be only one lane wide, and maybe it has to support only one loaded truck at a time. So what? If I can assume that a loaded tenton truck is three meters wide, the roadway on the bridge has to be only a little bit wider than that. If I can assume that a loaded ten-ton truck weighs seventeen tons, the bridge has to support only that weight. Anything else? I’m going to assume that they have no specific location for this bridge. So what? Site acquisition will be a major—and risky—part of this project.

How does the client describe the finished product? He doesn’t … at least not yet. So what? Maybe I can make some assumptions: If a ten-ton truck carries ten tons, and one ton of product is approximately nine hundred liters, that means that the bridge has to be available for only eleven loaded trucks each week. So what? Maybe this bridge has to be only one lane wide, and maybe it has to support only one loaded truck at a time. So what? If I can assume that a loaded tenton truck is three meters wide, the roadway on the bridge has to be only a little bit wider than that. If I can assume that a loaded ten-ton truck weighs seventeen tons, the bridge has to support only that weight. Anything else? I’m going to assume that they have no specific location for this bridge. So what? Site acquisition will be a major—and risky—part of this project.

![]() How does the boss describe the finished product? He doesn’t … at least not yet. So what? It looks like the bridge design is going to be a part of the project.

How does the boss describe the finished product? He doesn’t … at least not yet. So what? It looks like the bridge design is going to be a part of the project.

![]() What is the current state of the client? The boss hasn’t mentioned anything new, so I can assume that Glenfracas is still doing well and still satisfied with our previous work for it. So what? If all goes well, there should not be any surprises from the client. It has always turned the approvals around quickly and has always taken our word for the engineering. So what? That will really help on the risk analysis.

What is the current state of the client? The boss hasn’t mentioned anything new, so I can assume that Glenfracas is still doing well and still satisfied with our previous work for it. So what? If all goes well, there should not be any surprises from the client. It has always turned the approvals around quickly and has always taken our word for the engineering. So what? That will really help on the risk analysis.

![]() What is the current state of our company? We have a good track record, and none of our union contracts are up for renewal. Our plate was full until earlier this year, but we are at about 80 percent capacity right now. So what? I should have no problem finding the project team and project resources that I need.

What is the current state of our company? We have a good track record, and none of our union contracts are up for renewal. Our plate was full until earlier this year, but we are at about 80 percent capacity right now. So what? I should have no problem finding the project team and project resources that I need.

![]() What is my current state? In another two weeks, my role in the Glenwidget Tay River bridge project will be over, I just finished my annual vacation last month, and my evening classes for my postgraduate work do not start for another four months. Except for seeing our oldest off to the university next month, this project comes at a pretty good time.

What is my current state? In another two weeks, my role in the Glenwidget Tay River bridge project will be over, I just finished my annual vacation last month, and my evening classes for my postgraduate work do not start for another four months. Except for seeing our oldest off to the university next month, this project comes at a pretty good time.

![]() Is quality an issue? We have to meet government code, but if this is a private bridge there could be some leeway. Other than that, it will have to go all the way across the river and support the expected traffic. So what? There seems to be some opportunity for scope creep, but little room for surprises. And, in the end, this is not a constraint.

Is quality an issue? We have to meet government code, but if this is a private bridge there could be some leeway. Other than that, it will have to go all the way across the river and support the expected traffic. So what? There seems to be some opportunity for scope creep, but little room for surprises. And, in the end, this is not a constraint.

![]() Is time an issue? The boss hasn’t set any deadlines, but the client’s competitor seems to be moving into the same territory in the next few months. So what? I won’t tie my project’s success to someone else’s actions, but it may be necessary to constrain this project to three months. That’s another assumption to be checked.

Is time an issue? The boss hasn’t set any deadlines, but the client’s competitor seems to be moving into the same territory in the next few months. So what? I won’t tie my project’s success to someone else’s actions, but it may be necessary to constrain this project to three months. That’s another assumption to be checked.

![]() Is cost an issue? The boss hasn’t set any cost limits, but knowing the parsimonious culture of this part of the world, I fully expect to have to minimize the frills. So what? That should help keep this project simple and quick.

Is cost an issue? The boss hasn’t set any cost limits, but knowing the parsimonious culture of this part of the world, I fully expect to have to minimize the frills. So what? That should help keep this project simple and quick.

So, in preparation for the discussion with the boss tomorrow, what have we got?

The project goal is to build a “Bridge on the River Why.”

My assumptions that I will have to validate with the boss and the client are:

![]() Time is of the essence.

Time is of the essence.

![]() A loaded ten-ton truck is three meters wide.

A loaded ten-ton truck is three meters wide.

![]() A loaded ten-ton truck weighs seventeen tons.

A loaded ten-ton truck weighs seventeen tons.

The project’s critical success factors are:

![]() Complete the bridge on time.

Complete the bridge on time.

![]() Make it support a loaded ten-ton truck.

Make it support a loaded ten-ton truck.

The project’s critical success measures are:

![]() Complete the bridge within ninety calendar days.

Complete the bridge within ninety calendar days.

![]() Make it support seventeen tons.

Make it support seventeen tons.

The obvious project risks are:

![]() Insufficient time

Insufficient time

![]() Regulatory denial

Regulatory denial

![]() Regulatory delay

Regulatory delay

![]() Environmental issues

Environmental issues

![]() Site acquisition issues

Site acquisition issues

![]() Vendor performance failures

Vendor performance failures

![]() Resource availability

Resource availability

That ought to be enough until he calls tomorrow. I feel that I have a pretty good handle on what is in scope and what is not.