1 Understanding Internal Information Theft

A Case of Retail Business

1.1. Introduction

This book is about preventing internal information theft in retail business. We therefore begin by answering an essential first question, namely, What is information theft? We answer this question by discussing the concept of information theft, and we contextualise the theft within retail business. The expected second question is, Why should you bother with prevention of internal information theft? We answer this question by looking at overall impacts—socio-economic costs of internal information theft in retail business. These discussions are directed towards building the background to a basic question—How do you prevent internal information theft?—which is answered by subsequent discussions in the rest of the chapters.

1.2. What is Information Theft?

As it is expected from a fairly young area of research in business information security, there is not yet a universal consensus on the definition of information theft in retail business. We define information theft as stealing or an unauthorised access of personal identifiable details of someone else. For example, a retail company employee steals a customer’s card details, market plans, product design, etc. for his or her own personal interest. However, several definitions are increasingly adopted, and it is probably fair that most researchers in information security (IS), when asked to provide their definition, will provide their understandings of information theft based on various concepts.

Researchers suggest that the problem with establishing a widely accepted definition of information theft is that different individuals from different business operations have different concepts. Others seem to be subjective to different ideas and experiences when they discuss information theft. In particular, a majority of researchers opined that a contextual meaning of information theft is a necessary, if not a sufficient, factor in the study of information prevention; and for information security experts, the contextual knowledge of information theft is a must-have for understanding its prevention. Hence, there is a need to underpin the identity and identification concepts and terms surrounding information theft.

Raab (2008, p. 3) expresses the concept of identity as follows:

Identity and identification are not just specialist terms used only by researchers in our various technical discourses…. there is enormous and diverse literature that surrounds the term identity testifies to the growing importance of identity in the politics and social life of our time…, a fixed identity may be necessary if we are to function in daily life, and history attests to the severe difficulties that befall persons whose ‘papers’ have been destroyed or confiscated, and who therefore need to construct an identity…

The concept of identity as it is in the context of most social theory influenced the context of its discussion and analysis. Josselson et al. (2006) examined identity and states that: “identities are not fixed and frozen” as individuals evolve in time”. As defined by Burke (2008, p. 2), an identity “is a set of meanings applied to the self in a social role or as a member of a social group that define who one is”. Koops et al. (2009) define ‘identification of an individual’ as it attributes to ‘self’ as a vital element of identity explanation. They distinguished between ‘Idem Identity’ and ‘Ipse Identity’, defining them as the ‘sameness of persons or things’ and ‘personal identity in the meaning of an individual sense of self’, respectively.

This concept of ‘idem identity’ is adopted in the rest of this study. Information thefts are committed against what makes an ‘individual or an entity unique’, and this ‘individual uniqueness’ is what Goffman (1990) termed ‘Identity pegs’.

1.3. Internal Information Theft: The Contextual Issues

Just as the definition of the term ‘identity’ is not straightforward, neither is the definition of information theft. The tactic adopted in this book is to answer relevant questions to simplify the understanding of the complexity of defining information theft. The basic questions that constitute important elements in defining information are: Who are the individuals or groups that perpetrate information theft? How is information theft perpetrated? When and where is information theft perpetrated?

To answer the above questions about the place and circumstances surrounding information theft, the discussion needs to be extended to retail business as an organisational entity with respect to management (people) and operations (process). The distinctiveness of information theft in retail business is also imperative to consider in discussing the prevention of this theft. This is because an extensive number of different information theft-related crimes often include the use or abuse of identity, which includes credit card number theft, cheque cards, debit cards and phone cards, ATM spoofing, pin capturing, database theft, electronic cash theft, as well as identity theft-related frauds such as counterfeiting, forgery, postal fraud, financial fraud and plastic card fraud.

As information thefts have different meanings in private corporations and in public sectors, some have argued that credit card fraud and account hijacking should not be conceptualised as information theft, as will be discussed in the various contextual definitions below. Specifically, most financial institutions classify fraudulent use of stolen credit card numbers not as an information theft but as a payment card fraud.

To answer the above questions, the UK Home Office Identity Fraud Steering Committee (2006) posits that information theft occurs when personal identity details are stolen by a thief to support unlawful activity. In contrast, security researchers in the United States define information theft as a takeover of someone else’s personal identifiable information. In the same vein, in Canada, for instance, information theft must involve ‘a deprivation of an actual thing to the owner’, thus ‘copying personal information from a computer or official document for criminal use.’

Many states, Commonwealth agencies and territories consistently use the terms ‘identity fraud’ and ‘identity crime’ interchangeably to explain the meaning of information theft. Adopting a general definition of ‘identity theft and identity fraud’, as put by the Federal Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act USA, UK Home Office, and some researchers, might not be an acceptable or viable option. This is the reason for the general belief that the definition of information theft should be considered with respect to business context terms, location, region, and cultural background. However, some researchers argue that the most relevant issue is to explore the elements of these crimes and to relate them to the circumstances surrounding its occurrences with a particular business as an organisational entity. According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Expert Group (UNIEG) cited in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2008), in the term ‘identity fraud’, ‘the element of deception’ lies not only in the deception of technical systems and human beings to obtain the fraud but in the deception of victims in the subsequent use of the stolen information. However, there is still no standardised definition in the field of offences related to the theft of identity. As noted above, American literature always adopts the term identity theft to express information theft, whereas in the UK (HM Cabinet Office, 2002) and in other countries such as Canada and Australia, information theft can be described as the offence of identity fraud.

This difference in defining identity-related offences is still a big challenge in resolving the problem of information theft definition, as noted by Koops et al. (2009, p. 4):

…It is also not clear what exactly constitutes ‘information theft’ and how these can be combated…This lack of precision becomes especially apparent when comparing the various official media reports on these topics. Definitions are hardly ever provided, even though the statistics play a role in politically motivated discussions and policy decisions. Commonly accepted definitions are also lacking in literature. This means that we are at the stage where comparisons of apples and oranges abound making it virtually impossible to determine the real incidence of identity-related crimes…

Currently, the commonly cited definitions (although some could not be cited without critics) of information theft are as follows:

An individual is considered to commit an act of information theft when he or she “knowingly transfers or uses, without lawful authority, a means of identification of another person with the intent to commit, or to aid or abet, any unlawful activity that constitutes a violation of Federal law, or that constitutes a felony under any applicable state or local law.

(Federal Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act USA, 1998, title 18 United States Code—Section 1028)

The UK Home Office defines identity theft as an act which

occurs when sufficient information about an identity is obtained to facilitate Identity Fraud irrespective of whether, in the case of an individual, the victim is alive or dead.

(Home Office Identity Fraud Steering Committee, 2006)

In a more extensive approach, the UK Fraud Advisory Panel (2011, p. 1) states that the term

‘Identity fraud’ is commonly used to describe the impersonation of another person for financial gain. Fraudsters steal your personal identity and/or financial information and use it to purchase goods and services or access facilities in your name…, it is the use of a false identity or another person’s identity to obtain goods, money or services by deception. This often involves the use of stolen, counterfeit or forged documents such as passports, driving licences and credit cards.

In the Australasian Centre for Policing Research, James (2006, p. iii) defined identity theft as:

the theft or assumption of a pre-existing identity (or significant part thereof) with or without consent. It may involve an individual’s identity (whether a person is dead or alive), or the identity of a business.

The OECD (2008) expresses the similarity in the definitions in stating that: ‘information theft’ is a subset of identity fraud and that both ‘identity fraud’ and ‘identity theft’ are a subset of identity crimes. Moreover, the contextual range of identity theft-related crimes are much broader and they are certainly significant as the definition is unrestricted to any particular context. This definition buttresses the point made Gerring (2001, p. 54) that

a concept that applies broadly is more useful than a concept with only a narrow range of application’. A good concept stretches comfortably over many contexts; a poor concept, by contrast, is parochial—limited to a small linguistic turf.

In as much as the use of contextual perspectives surrounding information can be helpful to researchers in understanding the nature of information theft in retail businesses, the term ‘identity theft-related crimes’ is generally used in most literature (Meulen, 2011).

However, there are other terms used by researchers to describe information theft, such as ‘identity deception’—which arguably is not widely recognised because the term ‘deception’ neglects the role of the victim whose personal identifiable information is stolen. Nevertheless, the definition of information theft in this book is the ‘unlawful manipulation’ of technical systems as well as human beings by dishonest or disgruntled employees to steal another person’s identity to commit criminal offences. This book uses this definition as the basic reference for the subsequent subchapters.

The next sub-chapters explore some social theories which provide answers to questions about the nature of information theft in retail business as it is underpinned by the characteristics of perpetrators. Some vital theories that provide some interesting answers on ‘why’ motivations of information theft perpetrator are discussed, based on ‘how’, ‘when’ and ‘where’ these crimes are committed.

1.4. Understanding Internal Information Theft in a Workplace

Over the decades researchers (e.g., Cressey, 1973; Ditton, 1977; Mars, 1982, 2006; Gill, 2011) have used theories to provide a comprehensive conceptual understanding of workplace theft: how thefts are perpetrated in a workplace, how organisations adapt to theft-related crimes and why the perpetrators act in certain ways. The theories discussed in this section provide this book with different ‘lenses’ through which to look at information theft.

For instance, Mars (2006) focuses attention on different aspects of the issues of occupational deviance: cheating, fiddles, pilferage, scams and sabotage in the 21st century and providing a framework within which to conduct their analysis. The analysis provides an understanding of the nature of information from the context of occupational crimes and relates it to retail companies.

This subchapter contributes to the understanding of the nature of information theft by providing answers to the question of ‘why information theft’ in the retail businesses.

1.4.1. Internal Information Theft: Workplace Dishonesty

The evolution of the digital economy and changes in technology have direct impacts on the nature of workplace crimes. Computer-related crimes and internal information theft in this context are not the exception. Mars (2006) notes that, although the extension of information technology has undoubtedly reduced employee control in some jobs, it has radically increased their control in others. In his anthropological study of occupational crime, Mars (1974) applies Douglas’s (1970) concepts of ‘grid’ and ‘group’ to classify occupational structure in relation to workplace deviance. He divides employees into four categories based on the structure of their occupations. The first category is ‘the Hawks’, the workers who manipulate organisational rules to their own advantage. The typical examples of such workers are ‘the entrepreneurs, the innovative professionals and the small business owners’. The second are ‘the Donkeys’. The Donkeys are highly constrained by rules. They respond to the systems that constrain them by breaking them, ‘to fiddle or to sabotage the systems’.

The third category is ‘the wolves’. Mars (1974, p. 2) expressed this category as ‘the dock work gangs’, or ‘the work-and-pilfer’. They work in well-organised and highly regulated packs. Fourth are ‘the vultures’.

Examples are writers and travelling salesmen who work primarily in a supportive and corporative base. Although ‘vultures’ are highly competitive and individualistic, they fiddle in ways because of the nature of their job. These above categories which emerge from Mars’s (1974) study show ‘cheats’, ‘fiddles’ or ‘sabotages’ as being multifunctional. Mars (1974) suggests that workers under different categories engage in dishonesty or criminal acts so as to make an ‘unequal reward systems a bit more even’.

Mars cited instances in which workers justified ‘the fiddles’ as being indicators of occupational success and status, as satisfying punitive measures against employers, as being antidotes for boredom, as being ways of avoiding the delays and perceived injustices of clumsy bureaucratic systems, and as ways of increasing control at the workplace. Mars’s (1974) overall suggestion is that ‘the dishonesty’ at the workplace should be seen as being more than an index of employee dissatisfaction, that it should be seen as pointing to ways in which the criminal activities could be changed so as to bring employees into the centre of workplace control. Specifically, Mars (2001a) suggests that increases in control over the ‘the Grid Donkey jobs’—as in the call centres of the today’s online retail companies, for example, encourage dishonesty and deviance, particularly resentment fiddles.

Information technology, paradoxically, increases the power of such dishonest employees, who, if disruptive, can be resentful and prone to sabotage. In his agreement to the above contentions by Mars (2001a), Hollinger (1997) points out that behaviours of the dishonest employees in this computer age represent merely a ‘re-tooling’ of deviant and criminal activity. In other words, sabotage as a form of computer-related crime is not necessarily a new form of sabotage but a ‘re-tooling of the status quo’.

Mars (2006) suggests that a response to curb the behaviours of dishonest employees categorised above does not always prove to be effective. He noted that such behaviours need collective preventive action from workplace management in form of both ‘coercive technology’ and ‘technical up-gridding’ (Mars, p. 289). The above analysis of Mars (1974, 2001a) shows the importance of employing broad interpretations in explaining workplace deviance behaviours such as internal information theft, and not totally ignoring the covert occupational institutions and systems.

Mars (1974, p. 204) argues that

any management who introduce or propose a change to the workplace without considering covert reward systems are operating blindfold; examine and discuss ‘the way fiddles produce their own set of social relationship in the workplace and gauge the effect that any planned change would have on them.

This suggestion, in particular, is important. It underpins the rationale for exploring the theoretical analysis of the motivating factors that induce dishonest employees into internal information theft.

1.4.2. Internal Information Theft: Perpetrators’ Motive

Researchers (Newman and Clarke, 2003; Gill, 2011) noted that there are three major factors that induce the dishonest employees to steal the personal identifiable information. These include: a) Perpetrators concealment; b) Financial gain and rewards; c) Business environment; d) Economic Climate—Recession.

Concealment of the Perpetrators: Some perpetrators of information theft in retail companies have the mindset that such an environment avails them the opportunity to remain anonymous. Newman and Clarke (2003) noted that environmental factors offer substantial opportunity for crime, as summarised with the acronym SAREM: Stealth, Challenge, Anonymity, Reconnaissance, Escape and Multiplicity, shown in Table 1.1 below.

Financial Gain and Rewards: It is a general idea that personal identifiable information is a psychological construct used to identify particular individuals ‘uniquely’ (Cast, 2003). Personal information is a construct which has invaluable attributes of every individual. This definition points to the fact that victims of information theft have lost something more than just money; if the personal identifiable information (PII) of an individual could be conceived as a composition primarily of information that is unique, priceless and invaluable, then one perhaps begin to understand the motivation of information thieves. Clarke (1999) has conceptualised that personal identifiable information is a ‘hot product’ and that hot products attract theft. He demonstrated how personal identifiable information—a ‘hot product’, can be more prone to theft than others using the acronym CRAVED: Concealable, Removable Available, Valuable, Enjoyable and Disposable, as described in Table 1.2.

|

SAREM |

Concealment Attributes |

|

Stealth |

The perpetrators are almost invisible on the Internet, a condition for committing information theft (Denning and William, 2000). |

|

Anonymity |

With the information system being characterised with a decentralised database system which operates in an anonymised platform, this allows the employees to perpetrate crimes (Wortley, 1997). |

|

Reconnaissance |

This attribute is noted as perhaps the most important element that motivates criminals in most business organisations, as the information system makes it possible to scan thousands of database servers and even millions of personal computers that are connected, looking for the target victims. |

|

Escape |

This sums up other attributes owing to the crime-inducing aspects of the information system environment of anonymity, deception and stealth, thus making information theft in retail business difficult to be detected. Perpetrators perceive that it is easy to escape punishment (Ahuja, 1997). |

|

Multiplicity |

Unlike other traditional theft, which is relatively limited in nature, internal information theft can be multiplied exponentially because the perpetrator has access to a vast number of new opportunities. |

Retail Business Environment: Motivations in a workplace may be perceived as predispositions to particular behaviours and outcomes, reflecting the things employees want and the strategies chosen to achieve them (Thompson and Mchugh, 2009). Researchers (e.g., Lacoste and Tremblay, 2003; Newman, 2004) have identified business environments, such retail business (online retailing), as the major source that provides opportunity for individuals who steal personal identifiable information.

They classified the sources into two:

- Collection centres,

- Application centres.

|

CRAVED |

Financial Gain and Reward Attributes |

|

Concealable |

From the information systems (computer networks, intranet and Internet), one can steal personal identifiable information secretly without possessing it completely, and can do so from any accessible and convenient place. |

|

Removable |

With the intangible nature of PII, it is thus removable, movable and intrinsically vulnerable to interception and can be disguised to any desirable and intended forms by the criminals. |

|

Available |

The revolution of the Internet has made all information potentially available to everyone. Personal information and records are there for the taking. In fact, one does not even have to steal them. One can buy identification information as cheaply, breed other identification documents from them and then convert them into cash. |

|

Valuable |

Personal Identifiable information details (e.g., credit cards, bank passwords) in this current information society (e.g., retail and banking industries) is conceptualised as money. These are valuable items; thus they are targeted by criminals. |

|

Enjoyable |

Information thieves in a retail businesses are lured by the prospect of pleasurable living and rewards whenever stolen identities of the innocent clients or customers are converted into cash. |

|

Disposable |

Sutton, Cherney and White (2013) notes that the availability of a fencing operation enhances the chances of particular items being stolen. Unlike traditional stolen goods, with the attribute of continued possession increasing the risks of being caught, stolen information and the disposal of the PII is not so apparently pressing. The criminal continues to savour the gains of the stolen PII in hiding until the crime is detected. |

The Collection Centre/Point in a business environment is where the criminals steal personal identifiable information; the Application Centre is the point of use. Examples of the collection centres include: a business office via company databases and paper or electronic documents, business transactions via workplace environment and personal computers, financial statements via credit/debit statement and Internet, and data mining via abetted hacking. Moreover, other researchers (Davis, 2003; Newman, 2004) summarised characteristics of information thieves in relation to a business environment and based on their criminal activities, as described in Table 1.3.

|

Category |

Characteristics |

|

Incidental |

These are the amateur information thieves that take advantage of varied incidences—data leakages within the information systems, without any specific task-based intention (Perl, 2003). |

|

Opportunistic |

Amateur criminals with intention, without taking any risk. These criminals are not professionals, but they look for opportunities; if they get one, they would take it. In some cases they are referred as circumstantial or secondary thieves. These criminals often advance to professionals because of interest and financial gain from the initial act (Davis, 2003). |

|

Professional |

These are criminals with learned techniques with an in-depth knowledge of various methods to steal information (Morris II, 2004). |

|

Gang |

These are criminals in the form of an organised group, comprised of several experts from suitable fields (e.g., Computing, Psychology). This form of thieves is offensive with a high level of commitment (Newman, 2004). |

|

Seller |

These are thieves that sell personal identifiable information such as credit/debit cards, e-mail address, driver’s licence, home address, etc. |

Economic Climate—Recession: Gill (2011) argues that there is some evidence that characteristics of an adverse economic climate can lead to either an increase or a decrease in crime. Gill suggests that because there is a possibility of the unavailability of credit due the recession, there is a likelihood that such an economic climate will create opportunities for fraud. Leslie and Hood (2009) agree with Gill (2011) and argue that if dishonest employees have less disposable income during recessions due to redundancy during recessions, they would be motivated to indulge in information theft. In contrast, Yeager (2007) argues that there should be caution in supporting the hypothesis that recession leads to an increase in crimes. Gill (2011) also cautions that care should be taken in generalising his suggestion because different crimes are influenced by different issues.

Gill (2011) and Yeager (2007) suggest that it is necessary to look into other theories that discuss the criminal motive behind the increase in crimes. Various researchers (e.g., Cressey, 1973; Kantor, 1983; Black, 1987; Brooks and Kamp, 1991; Kardell, 2007; Clarke, 2009) have used theories to analyse other motivating factors and situations that could induce employees to steal personal identifiable information. It is important to look into some of the theories that motivate crimes because they provide an analytical explanation of an employee’s behaviour based on the key elements: environments, situations and time. These elements (environments, situations and time) answer the key questions of where, when, why, and how as they relate to the nature of internal information theft. Some relevant theories include:

- Cressey’s Fraud Triangle;

- Person Theory;

- Workplace Theory.

Cressey’s Fraud Triangle Model: In his theory of ‘the triggers’ that lead to theft-related crimes, Cressey (1973) pointed out that each criminal has motives and opportunities that induce them to commit crimes. He models a ‘Fraud Triangle’ of which each side represents components of what causes the perpetrators to commit crimes. The three components are Rationalisation, Perceived Opportunities and Social Pressure facing the individuals. Cressey (1973) explained that rationalisation and social pressures are the key attributes that motivate the employees’ attitudes towards crimes. Kardell (2007) also suggested that, whereas perceived opportunities might be managed by the organisations, rationalisation and social pressures are generally beyond the control of the organisations.

Person Theory: This theory uses the concepts of Opportunity, the Marginality Proposition, and the Epidemic of Moral Laxity to explain why some employees may indulge in internal information theft. This theory could be extended to the prevention of internal information theft through personnel exclusion.

The summary of the interpretation of these approaches is presented in Table 1.4 below.

Workplace Theory: This theory contributes by explaining the reasons that some businesses, online retail companies in this case, suffer higher levels of internal identity theft-related crimes. Hence, the analysis provided by the workplace theory, which is situation specific, could lead to the evaluation of different systematic strategies for controlling and preventing internal information theft.

Workplace theory explains the motivation of disgruntled employees who engage in internal information theft based on the concept of the Workplace Theory shown in Table 1.5 below.

1.5. Perpetration of Internal Information Theft

Subchapter 1.3 has provided knowledge of concepts and theories of the nature of internal information theft in the workplace while identifying the importance of this knowledge in understanding the motives of internal information thieves. While it contributes, in part, to answering the question of why there is internal information theft in retail businesses, this subchapter looks more in-depth on the perpetration. It provides an understanding of who, how and when internal information theft is perpetrated, and who detects the theft in relation to its prevention. With increasing cases of internal information theft, business owners and researchers continue to ask: why is this risk growing? To answer this question, it is important to reflect on the motivations of internal information theft discussed in Subchapter 1.3.

|

Person Theory’s Components |

Explanation of the Pearson Theory in Relation to the Nature of Internal Information Theft |

|

Opportunity |

Cressey (1973) and Kantor (1983) claim that opportunity correlates positively with nature of internal information theft and other related crimes. In agreement, Kardell (2007) argues that minimised opportunity like constant surveillance over employees’ activities could be an internal information theft deterrence. This theory pointed out that employees, as humans, have greedy instincts. And this could be translated to theft if there is an opportunity at the employees’ disposal. |

|

Marginality Proposition |

This approach holds that the employee’s degree of marginality could cause internal information theft within organisations (Clarke, 2009). Social isolation, little opportunity for advancement, short tenure, low rank in the organisational hierarchy, low wages, expendability, little chance to develop relationships, etc. are characteristics of marginal employees. Employees that fall in this category are more likely to indulge in internal information theft. |

|

Epidemic of Moral Laxity |

This approach postulates that moral decadence in society today leads to moral laxity in organisations (Clarke, 1999). Newman and Clarke (2003) support this concept and suggest that employees of decades ago possessed more trustworthy qualities than the employees of today. |

Rationalisation, opportunity and social issues have been identified as the key motivating factors for perpetrating internal information theft. A greedy (social issue) employee working in an unsecure IT infrastructure (opportunity) believes (rationalises) that s/he may not be caught for indulging in the theft. The perpetrators would be motivated to act because of the nature of retail business operations which are carried out using the Internet—activity behind the computers. Other major motives include gambling lifestyles or pressing bankruptcy and debts. Having the opportunity to steal prepares the fraudulent employee to look for the situations that would pay off. For instance, some of the perpetrators, irrespective of gender, either obtain temporary employment for the sole purpose of internal information thefts or place organised criminals in the business organisations to gain knowledge of the firms’ information systems in order to steal critical information. Hinds (2007) suggested that the structure of a firm’s Information Systems and Data Protection Policy is among the key enabling elements that may encourage internal information theft. These elements are interrelated such that one situation or an opportunity for internal information theft may lead to another.

|

Workplace Theory |

Workplace Theory Explains Internal Information Theft |

|

Perceived Fairness |

This model points to a relationship between employees and perceptions of organisational fairness. Tucker (1989) notes that theft can be better characterised as a mode of social counter-control rather than a crime. In this context, information theft is seen as a response to the perceived deviant attitude of the employer. This theory argues that the exploitative behaviour of an employer is the cause of the stealing. Hence, employees’ admissions of internal information theft might be associated with job dissatisfaction. |

|

Climate and Structure |

This approach is suggested by Brooks and Kamp (1991). It argues that organisational climate encourages a dishonest attitude (Johns, 1987). Employees’ perceptions about the work climate, their co-workers, attitudes of their supervisors and management can send messages to them about whether the crimes might be condoned or not. Shearman and Burrell (1988) note that the structure of IT security affects the propensity of employees to steal the organisation data. The more complex the security of the information storage, the fewer cases of internal information theft. |

|

Deterrence Doctrine |

This concept holds that internal information will be more likely to be perpetrated in an organisation where there is low awareness of anti-crime policies. Kantor (1983) supports this approach that employees’ behaviours are influenced by the threat of organisational sanctions. According to Greenberg and Barling (1996), the most effective variable of this approach in deterring internal information theft is the perceived certainty of punishment among other variables: perceived severity and visibility of punishment. |

Structure of Information Systems

Perpetrators of internal information theft often target and exploit weaknesses in retail business operation because of the structure of the information systems and the business policy. The modern information systems architecture of tye retail sector is often designed to store the customers’ data in one place which could be accessible to employees in a variety of departments. It is generally built with a structure of distributed information systems in which networked computers communicate and interact with each other to achieve the common goal of their business transactions.

This design may result to the consolidation of diverse customers’ information that might be of easy access to thieves (Duffin et al., 2006). It makes it easier and quicker for perpetrators to have comprehensive information about the customers’ data at a glance. This structure also creates opportunities for organised criminals to target employees in the information system department of the retail companies.

Data Protection Policies

More than a decade ago, Judith Collins argued in the case of the US department of Justice that information theft-related crimes are escalating because of the lack of a definitive policy. Due to the definition problem in the context of internal information theft, some law enforcement agencies were not able to record internal information theft as a separate crime from other computer-related crimes. And because of the nature of computer-related crimes as cross-jurisdictional issues which may span or cover several geographical areas and business networks, the mitigation may have led to confusion about who is responsible for investigating and prosecuting such crimes.

In some cases, this leads to the victims of information theft reporting the cases to the wrong enforcement agencies. For instance, in the case of information theft involving bank details, victims are likely to report the case to the financial crimes investigation agency rather than to the police. The issue of undefined data protection policies and jurisdictional or management roles makes the loss related to internal information theft more impactful. For instance, most outsourcing firms run into difficulty in offering a personal identifiable information monitoring service for their customers because some employees within the retail companies thwart credit-monitoring processes based on the stipulations that the outsourcing firms (third-party firms) are not part of their statutory data protection policy. Such circumstances contribute to the identity monitoring service arriving days after these crimes activity have transpired.

1.5.1. Methods of Perpetrating Internal Information Theft

Researchers (e.g., Mitnick and Simon, 2006; Green-King, 2011) suggest that infiltration, collusion, coercion and social engineering are the common methods used by internal information thieves in retail companies. These methods can be carried out independently or combined with other mechanisms. For instance, with collaboration and social engineering, combined, internal information thieves can generate phishing web pages for nearly any online retail company at the click of a mouse or the tap of a key. APWG1 (2014) suggests that some internal information thieves often succeed in manipulating the IS by using various techniques.

Common techniques include the use of unapproved hardware/devices, abuse of private knowledge, violation of e-mail/IM/web/Internet policy of the victims, handling of data on unapproved devices/media, storage/transfer of unapproved content and use of unapproved services/software. In addition, APWG indicates that a majority of the perpetrators use botnets to commit PID2 account fraud and privacy counterfeiting, through networks of IS and machines with malicious programmes in the form of phishing attacks. Table 1.6 summarises common mechanisms for perpetrating internal information theft.

1.5.2. Other Methods of Internal Information Theft

Other methods used for stealing information are phishing, repairmen and elaborate yarns to hoodwink the human resources staff into providing the company’s PII assets. The key technical modes used by the outsiders/external agents who were abetted by malicious insiders include malware, hacking, social engineering and physical actions. Although some online retail companies may implement elaborate authentication process, firewalls, networking security monitoring technology and virus scan software, their IS may still be porous to incidents of internal information theft due to collaborative and colluded practices of employees and external agents. In addition, with the aid of dishonest employees/insiders in the target retail company, the external agents and dubious information security experts and their accomplices could equip themselves with evolving technical tools to manipulate the systems.

Due to the techie knowledge of the employees (software engineers, IS/T administrator), they often exploit the IS weaknesses related to configuration, functionality or application. The CIFAS (2011) and Verizon Risk Team Survey Report (2012) indicated that in the use of phishing (via pretexting and solicitation) as an information theft vector of choice, external cybercriminals relied on the personal touch, with more than 78 per cent of internal information theft cases involving in-person contact. They noted that even in the high-tech business world, all facets of cybercrimes would not get done without an in-person ‘meet and greet’.

|

Methods |

Explanation |

|

Infiltration |

This is a mechanism whereby organised criminals plant the agents in the retail companies. The planted criminals (outsourcing agents, vendors, and partners) could gain employment to commit internal information theft. The factor behind this method could be linked to the commercial pressure or to high employees turnover in online retail (Green-King, 2011). The pressure can open the door for an influx of deliberate criminals in retail outlets and call centres. Green-King (2011) suggests that less stringent vetting and recruitment control measures encourage infiltration. tc “Infiltration” f C l 1This situation is often difficult to detect. The perpetrators often resign before the detection. Some criminals lease or sell the compromised data. |

|

Collusion |

Organised criminals and the dishonest collude with fellow employees (in some cases with dismissed employees or business partners) who have access to personal and business information systems—payroll, account details, business transactions and records. It is a common approach used by some criminals of the same cultural background (Hinds, 2007). The meeting point is often at lunchtime, in nightclubs or pubs and at social events. tc “Collusion” f C l 1 |

|

Coercion |

Organised criminals intimidate and threaten employees to partake in internal information theft-related crimes. In some cases, call centre employees of the same company are being threatened by the top managers. Some employees who become involved in this fraudulent activity often claim that they did so under duress. Successful coercion often leads to collusion with the collaborators. Hinds (2007) suggests that 45 per cent of the internal information theft cases in the UK are coerced, of which 15 per cent admitted to having been paid to compromise their customers details. Some of the innocent employees (e.g., cashiers and wait-staff) were often coerced to skim payment cards. There were reported cases of recruiting the IS/T administrator for the purpose of stealing data, opening IS/T holes and disabling security systems. Verizon DBIR (2013) indicated that pretexting was one of the common elements of social engineering modes used in information theft perpetration. |

|

Social Engineering |

Act of pulling a con job to get access to an information system that is normally accessible by the privileged users—employees. Several researchers (Savage, 2003; Duffin et al., 2006) have noted that the perpetrators that use this method of internal information theft are often linked with an internal employee as an agent. This mode often involves social tactics—deception and manipulation—in exploitation of the roles of the human elements and end-users. These modes of information theft are often linked to both the technical and non-technical modes, alongside collusion of the perpetrators with external agents for successful exfiltration of victims’ personal information. Checkpoint (2013) suggests that employees are paid in some cases to get access to critical business data/information, because the external agents perceive that stealing of personal identifiable information would be impossible without the aid of the internal employees. Check Point (2013) indicates that 42 per cent of UK companies have been hit by social engineering attacks and that new employees (52 per cent), and the outsourcing agencies and contractors (44 per cent) are the most vulnerable agents. |

|

Patchable Software Vulnerability (PSV) |

Verizon Data Breaches Investigation Report (DBIR) (2013) notes that PSV is one of the key methods of stealing business information and customers personal identifiable information (PII). Verizon DBIR (2013) discusses the summary of the Verizon DBIR from 2008 to 2013, which shows that web applications, remote access and desktop services are the commonest pathways or vectors through which PII could be stolen. This report emphasises the role of human errors when privileged users manage these vectors in online retail companies. This evidence shows that remote access and desktop services combined with exploitation of default/stolen credentials are very rampant in retail companies. It can be concluded that opportunistic internal information theft incidents (intrusions) are common in retail companies that often share the same IS/T support with software vendors. With knowledge of a vendor’s authentication methods and schema (e.g., TCP port 3389 for RDP; or TCP port 5631 and UDP port 5632), internal information thieves (system administrators) can exploit (without traces) across the full range of the vendors/partners/outsourcing companies (Peretti, 2009). |

For some of these methods (e.g., social engineering and patchable software vulnerability) of carrying out internal information theft to be successful, Verizon’s Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) (2012) suggests that the perpetrators have to depend on the insight provided by the insider, who may have comprehensive knowledge of the target retail companies.

In some internal information theft cases, these methods could lead to advance persistent threats (APT) techniques such as Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS), botnets and zombies, Social Network Attacks, Clickjacking / Exploit kits/Crime packs, Infected Near-field communication (NFC), Scareware—fake security software warnings. CSO Magazine (2011) agrees that in cases of information theft, those that were linked to APT were perpetrated through sending internal data information to the external site/entity, tampering with the command/control channel, disabling/interfering with security control, stealing of login details, Sequel Query Language (SQL) injection and key-logging procedures and abuse of system access/privilege.

1.6. Targeted Assets by Internal Information Criminals

It is imperative to discuss internal information theft in relation to assets/data types. There was almost no report that indicated categorically the features of personal identifiable information/data (PII/D) stolen in retail businesses.

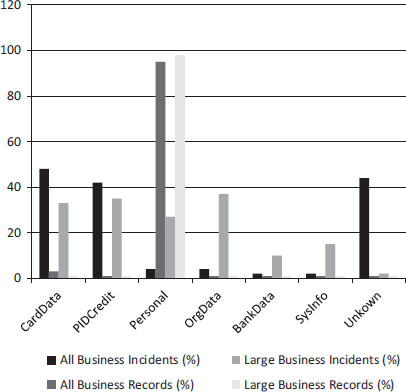

There were always issues of concern in relation to privacy of PII/D owners, mostly in relation to records containing names, e-mail address, source codes, etc. However, CIFAS (2013) indicates that the majority of internal information theft incidents involve stealing of the payment card information (containing names, e-mail address, source codes.) and authentication PID/I credentials. Dean et al. (2011) noted that some companies’ product patent and formulas are often stolen by internal thieves and sold at the cheapest rate on online auction websites. Some are sold at about 70 per cent off the patented versions on the online black market. Table 1.7 shows the variety of compromised IS/T assets classified by those that occurred in all businesses (irrespective of the size) and in big business, and by PID/I name, incident and record.

Figure 1.1 derived from Table 1.7 shows a chart of the targeted personal identifiable information and assets which have the highest records of compromise in both all and large business cases—95 per cent and 98 per cent, although these cases are associated with 4 and 27 respectively. In some cases, top business executives used their company’s name to secure a fraudulent transaction. Sometimes these incidents bring brand dents to the company, not only financial lost. The Lloyds Bank ex-head is a typical instance. In June 2012, the former head of Lloyds’ online security (Jessica Harper) was jailed for five years for internal information theft related to account-take-over and account-withdrawals. Jessica Harper was convicted for submitting some 93 bogus invoices.

1.7. Internal Information Thieves: Who Are They and Where Are They?

Metropolitan Police Operation Sterling MPS (2009) reported that employees who had been employed less than one year are more likely to collaborate with senior colleagues to steal personal identifiable information (PII). CIFAS (2011) suggested that some employees use their management positions and responsibilities because of their authority and access to unlimited information systems operations. Cases of internal information theft can be categorised based on the operation units of some retail companies.

From Table 1.8 below, retail stores, customer contact centres and field units are among the most targeted online retail business areas for information theft perpetration. This report corresponds with the Fighting Retail Crime Report (2012) which suggests that among 40 per cent of the companies interviewed, more than 25 per cent of their total internal information theft perpetrators were supervisors, security officers and senior administrators, of which 56 per cent held technical positions. Seventy-five per cent of the perpetrators were current employees and 65 per cent of these perpetrators occupied other positions with other companies.

|

Job Roles of Information Thieves |

Percentage of Internal Information Theft Incidents (%) |

|

Regular Employee/End-User |

61 |

|

Finance/Accounting |

22 |

|

Executive/Upper Management |

11 |

|

Helpdesk |

4 |

|

System/Network Administrator |

2 |

|

Unknown |

1 |

|

Others |

1 |

Table 1.8, which was adapted from Verizon RISK Team Survey Report (2012), shows the distribution of internal information theft by per cent of incidents in relation to their employment position. It shows that regular employees and end-users are the categories of employees that are more likely to steal because of their job roles and operations.

Other examples of regular employees include corporate end-users—call-centre employees, who take advantage of their IS access/user privileges and use them to seek cashable forms of personal identifiable data/information (PID/I), such as bank account numbers and payment card data. This report suggests that information thieves need not be super-techie-users or the most trusted of information systems users to manipulate information systems.

While accounting/finance employees are noted to indulge in information theft due to their position or their accessibility to personal accounts and financial forms and records, IS administrators/developers have been noted as a significant per cent of the perpetrators. ‘Others’ in Table 1.8 means incidents of internal information theft indulged in by business partners and outsourcing firms.

Verizon RISK Team Survey Report (2012) also shows that in retail industry alone, 22 per cent of internal information thefts are perpetrated by partners/remote, vendors, and outsourcing companies who are responsible for managing the point of sale (POS). The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE, 2014) agrees with this report and suggests that most internal information theft-related fraud schemes involve the accounting department or upper management. The ACFE (2014) indicates that more than 30 per cent of fraud cases are committed by the accounting department and over 20 per cent by the upper management or executive-level employees. The next commonly cited are employees from the digital marketing and sales departments. Forrsight Survey Report (2013) on the distribution of employees indulgent in information theft (in relation to department) agrees with the Verizon RISK Team Survey Report (2012).The Forrsight Survey Report (2013) indicated that the number of current employees abetting former employees in indulging in internal information theft is on the increase. Such perpetrators often sell the retail company’s IS/T credentials (access codes, authentication processes, de-provisioning of user accounts procedures) to the online ‘black market’.

The Forrsight Survey Report (2013) categorised ‘likely internal information thieves perpetrators’ in business organisations into four groups: Rogue, which comprises 9 per cent, HERO—the Highly Empowered, Resourceful and Operative Employees, comprising 16 per cent, Disenfranchised, which comprises 34 per cent and the Locked-down, with 41 per cent. This report suggests that Rogue and Locked-down perpetrators comprise 50 per cent of the total employees who pose the greatest internal information theft risks. The CIFAS Report (2013) suggests the following attributes of internal information thieves: male employees aged 25–30, fully employed, low paid, working in junior non-management, possibly in financial difficulties and possibly having worked in the victimised business organisation for less than a year.

CIFAS (2013) adds that 78 to 98 percent of intellectual properties theft out of overall internal information theft cases were perpetrated by male employees. This report corresponds with FraudTrack’s (2012) report that intellectual properties theft cases are dominated by male employees, with women linked to 18 per cent of reported cases.

1.8. Internal Information Theft: The Resulting Fraud Practices

In most internal information theft cases, the perpetrators use the stolen assets for financial gain. In other cases, they use the stolen assets to create bank accounts or apply for fraudulent loans, or they sell the data on the black market. Fraudulent account withdrawals and account disclosure have become common fraud practices that result from internal information theft. CIFAS Report (2012) indicated that there is an almost 50 per cent rise in the number of cases of internal information theft compared to the previous years, which account for as many as 80 per cent of all computer and Internet related crimes.

Fraudulent Account Withdrawals: Fraudulent Account Withdrawals involve unauthorised access to or manipulation of customer account information details for personal benefit. Other practices linked with Fraudulent Account Withdrawals are fraudulent account transfers to the employee account and fraudulent account transfers to a third party.

Disclosure of Commercial or Personal data: This involves the use of a commercial or business identity’s data without the consent of the data owner. The use of these data for unauthorised purposes always places the victimised companies and individuals at an operational risk and in financial difficulties, respectively. This is the case of the employee colluding with organised criminals to compromise customer data and information. The criminals could use the data to plunder the victim’s account by making multiple applications in their names.

The UK CIFAS claims that intelligence from law enforcement agencies has unveiled the infiltration of organised criminal groups in businesses as responsible agents for the disclosure of commercial and personal data.

In a summary of the common forms of fraud practices resulting from internal information theft, the UK Fraud Advisory Panel classified common types of internal information theft-related crimes into two categories: corporate information theft and personal identifiable information theft. Table 1.9 summarises the two categories.

|

Category of Information Theft |

Common Types and Schemes |

|

Corporate Information Theft The impersonation of another company for financial or commercial gain. Fraudsters steal a company’s identity and/or financial information and use it to purchase goods and services, obtain information or access facilities in your company’s name. |

Company hijacking: A fraudster submits false documents to a retail company to change the registered address of their employer company and/or appoint ‘rogue’ directors. Goods and services are then purchased on credit, through a reactivated dormant supplier account, but they are never paid for. |

|

Company Impersonation: A fraudster impersonates a retail company (sometimes by purporting to be a director or key employee) to trick customers and suppliers into providing personal or sensitive information, which is then used to defraud the retail company. In some cases, the retail companies may be impersonated using phishing e-mails, bogus websites and/or false invoices.

|

|

|

‘Personal identifiable information theft’ is commonly used to describe the impersonation of another person for financial gain. Personal identity criminals steal your personal identity and/or financial information and use it to purchase goods and services or access facilities in someone’s name. This scheme uses a false identity or another person’s identity to obtain goods, money or services by deception. This often involves the use of stolen, counterfeit or forged documents, such as passports, driving licences and credit cards. |

Application Fraud/Account Takeover: A fraudster applies for financial services (e.g., new credit cards or bank accounts) using an individual’s name or changes the individual’s postal address. Impersonation of the deceased: A fraudster uses the identity of a deceased person to obtain goods and/or services. |

|

Phishing: A fraudster sends an e-mail to an individual claiming to be from his or her bank or other legitimate online business (e.g., a shop or auction website) asking the individual to update or confirm his or her personal or financial information, such as password and account details. This information is then used to impersonate the targeted individual and gain access to accounts. |

|

|

Present (Current) Address Fraud: A fraudster living at your address (e.g., a family member) or nearby (e.g., a person living in the same block of flats) uses your name to purchase goods and/or services and intercepts the mail when it arrives. |

Case Study 1.1 A Comparative Case of the UK Fraud Advisory Panel, CIFAS and IdentityForce on the Categories of Internal Information Theft

The categories of internal information theft depend on the various intentions of the perpetrators. Some of the intentions are deliberate with malicious intent; inappropriate and not malicious intent; and unintentional without malice. Verizon DBIR (2013) agreed with the UK Fraud Advisory Panel (2011) and indicated that 93 per cent of internal information thefts were linked to deliberate malicious activity. This report noted that some interconnected intentions drive ‘the inappropriate’ and not malicious intent, and unintentional without malice. Under the category of those perpetrators with malicious intention, three-quarters of them had authorised access to the information stolen, with approximately 19 per cent of the cases involving either collusion or collaboration with outside accomplices.

In contrast, the CIFAS Report (2011) has earlier claimed that that internal information criminal might have had different intentions. CIFAS reports that 35 per cent of the perpetrators stole from their employers to gain a new job, of which 25 per cent of these perpetrators gave the stolen assets to the new companies. In addition, IdentityForce (2014) claims that in 25 per cent of internal information theft-related crimes, the perpetrators were actively recruited by someone outside the targeted company, of which 65 per cent were coerced at their workplace, 15 per cent were coerced remotely while accessing their employers’ networks from their homes or other location, and more than 25 per cent of the coercion location remained unknown.

1.9. Impacts of Internal Information Theft in the Retail Business

This section answers the question of why you should be bothered with prevention of internal information theft. It looks at the socio-economic costs of internal information theft in retail business. The discussion in this section is based on research findings and business case studies and reports. The evolution of e-businesses has left their customers vulnerable to internal information theft-related crimes, which leave countless victims in their wake, including online retail companies. In the 1990s, when the first third-party services—First Virtual, Cybercash, and Verisign—for e-business transactions were introduced, Greenberg and Barling (1996) noted that about 62 per cent of employees perpetrated information theft in e-businesses. Recent studies hold that internal information theft is on the rise (Skolov, 2005) and that as many as 70 per cent of information thefts are committed in the workplace (Collins, 2006). CIFAS (2013) suggests that the socio-economic costs of information theft to retail businesses are inestimable. Due to increasing incidents of internal information theft-related crimes across world regions and business sectors, it is arguably difficult to record actual socio-economic costs. The costs range from irreparable brand damage to psychological damage to the victims, to name but two.

1.9.1. Internal Information Theft: A Global Retail Business Issue

Cases of internal information theft in businesses across the world have not decreased in the past decades. KPMG, Kroll and CIFAS Joint Survey suggest that information theft and employees’ fraud-related losses cost more than $1.4 million per one billion US dollars of sales (Kroll Global Fraud Report, 2013).

This survey indicates that information theft and internal financial fraud are top rated irrespective of the world regions, except in the Pacific East, where intellectual property (IP) counterfeiting and collusion are of high percentages. This is in line with the findings of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), cited in Wells (2010), which suggest that a majority of businesses lost 5 per cent of their annual revenue to information theft—which accounts for more than 80 per cent of 1, 900 cases of employee’s fraud. Identity Theft Resource Centre (2008) reports that internal information theft costs businesses across the world about $221 billion annually, with businesses in the UK and the United States losing over £3.2 billion and $50 billion respectively per annum.

In Canada, information theft is rated the fastest growing among other crimes (Cavoukian, 2013; Hille et al., 2015). In Australia, the cost is estimated to be more than $3 billion, of which businesses losses accounted for between AUD$1 billion and AUD$4 billion (Queensland Police Service Police (QPS) Major Fraud Investigative Group, 2009). The Queensland Audit Office attributed this cost to the muddled attitude of the most top business managers, who generally believe that information theft-related crimes are principally carried out online by hackers and their collaborators (Walliker, 2006; Passmore, 2009; Prosch, 2009). In contrast to the Australian case of information theft, the Organised Crime Strategy Report (OCSR) (2005–2009) suggests that more than 80 per cent of the senior executives admitted that they have been hit by several cases of information theft-related crimes. From this OCSR’s survey, information theft cases accounted for the record loss by surpassing any kind of staff fraud for the first time in four year of OCSR’s survey history. This report further notes that 48 per cent of these top business executives agreed that risks of information theft dissuaded their contemporary retail business entries across the world. Potter and Waterfall (2012) suggest that many business leaders have spent more than £38 billion as part of global cyber security strategies for the prevention of information theft.

Case Study 1.2 Impact of Internal information Theft on UK Retail Businesses

The UK National Audit Office Report (2013) on cyber security strategy suggests that cybercrime costs more than £27 billion per annum with the majority of this cost (£21billion) attributed to information theft from UK businesses. National Fraud Authority (NFA) Report (2013), which uses systematic research techniques to analyse employee-related fraud, has estimated that fraud loss against UK businesses is more than £73 billion per annum. In this report, identity theft-related crimes accounted for 14.1 per cent, while 31.3 per cent of this loss is associated with internal information theft.

Based on the UK’s Staff Fraudscape by Hurst (2010), which estimated the cost of internal information theft in UK businesses to be £3.2 billion, it can be arguably concluded that the cost of information theft to UK businesses has increased by sevenfold since 2010. In as much as the costs for information theft are on the rise, so are the numbers of victims. Kroll Global Fraud Report (2013) indicates that 48 per cent of businesses in the UK are victims of information theft. This report agrees with the CIFAS: Fraud Prevention Fraud Service (2012) that the UK is second to Iceland with the highest cases of internal information theft amongst 25 nations, which in turn supports Hub International’s (2010) report that internal information theft has become one of the fastest growing types of employee fraud in the UK. CIFAS (2012) indicates that there is a more than 50 per cent rise in the number of cases of information theft compared to previous years, which account for as much as 80 per cent of all computer and Internet related crimes.

Identity Theft Resource Centre (ITRC) (2008) noted that lack of reliable guides and research resources on information theft-related crimes have been the major challenges of, and may continue to inhibit research into, possible intervention strategies. ITRC’s Identity Theft: The Aftermath (2005–2008) has consistently argued that business stakeholders in some cases declined to report internal information theft cases to law enforcement in order to protect the name of their organisation. This argument was supported by Dean et al. (2012) in their interview of 850 senior-level executives to examine the impact of internal information theft on their companies’ brand names. Dean et al. (2012) found that for business brands with a worth between $1 million and $10 billion, the average minimum loss associated with information theft was worth 12 per cent of their brand value. This report supports the argument of ITRC (2008) in relation to the reason that some business managers refuse to admit the scale of internal information theft-related crimes. They tend to protect their jobs and their business brand’s name from potential reputational damage. IBM Research agrees with this argument that business managers protect their reputation and reported that 73 per cent of IS employees fear losing their job if there is reported case of internal information theft in their companies (Chen and Rohatgi, 2008).

1.9.2. Internal Information Theft: A Case of Online Retail Companies

It is not uncommon to report a continuous rise in the cost of information theft in the online retail sector. Kroll Global Fraud Report (2013) identified online retail as one of e-business sectors where the incidents of internal information theft-related crimes are prevalent. In line with Kroll’s (2013) report, the BRC (2013) survey indicates that retail fraud has increased, with internal information theft on the rise and that one in three consumers do not shop online because of perceived online retail information security loopholes.

Case Study 1.3 The Cost of Information Theft to UK Retail Business

The British Retail Consortium (BRC, 2015) estimates the cost of electronic crimes (including internal identity theft-related crimes) to the retail sector by surveying UK retailers that, it stated, were responsible for 45 per cent of online UK retail sales. BRC estimated total losses of over £603 million to retail crime in 2013–2014. BRC also estimated total losses of over £205 million in 2011–2012. These estimates largely focused on losses from internal identity theft-related crimes and e-commerce frauds, as retailers were unable to estimate losses from cyber-dependent crimes.

Levels of crimes increased by 12 per cent in 2013–2014, with 135,814 incidents reported during the year, accounting for 37 per cent of the total £603 million cost of retail crime. The total cost comprised £77.3 million in direct losses (e.g., identification-related frauds, card and card-not-present (CNP) frauds and refund frauds), £16.5 million in security costs and £111.6 million in lost revenue from fraud prevention (caused by online retail security measures, such as driving away legitimate purchases). At the same time, the level of in-store theft has risen in 2013–2014 with an average of £241 per cent, 36 per cent up from the same time the previous year. These estimates bring the direct cost of retail crime to 3 million offences against UK retails during 2013–2014.

These findings agree with Shah et al. (2013) that issues of privacy related to security concerns are a major challenge for retail companies. These security issues in retail businesses have geared up the increasing cost of information theft, which has not decreased for a decade. For instance, in the case of UK retail companies, the cases of information theft have continued to rise in more than a decade. In 2004, the estimated cost of information theft to UK retailers was estimated at £498 million, which is double the £282 million estimated in 2003 (CIFAS: Staff Fraud Report, 2012), outweighing other business sectors by comparison.

The above reports and case studies support Stickley’s (2009) suggestion that cases of information theft are considerably greater in number in online retail than in other business sectors due to the modes of its business operation. In contrast to the causes of rising information theft cases that have been linked to retail business operation by Stickley (2009), the CIFAS Fraud Report (2011) noted that 76 per cent of retailers agreed that the increase of information theft incidents might be linked to recent economic crises. This report revealed that there is an increase of 19.86 per cent of information theft cases in 2010 compared with the figures from the first quarter of 2009. This report suggests that more than 70 per cent of internal information thefts accounted for the total number of computer-related frauds committed. This report also corresponds to Gill’s (2011) suggestions that the tendency of employees to engage in information theft-related crimes is due to the current adverse global economic climate.

The impacts of information theft losses and damage are inestimable. In some cases, businesses were unable to recover the cost of the damage, especially smaller businesses like online retailing, where internal information theft-related crimes discourage emerging smaller retailers from going into e-commerce (Yuan, 2005).

Case Study 1.4 Information Theft Incident Prediction for 2015–2016 in the UK

Some of the 30 per cent of retailers questioned by BRC suggest that internal information theft-related crimes, including cyber-enabled fraud, will be the most significant information security-related threats in 2014–2015 and 2015–2016. This prediction suggests that theft by staff would increase by 10 per cent, theft of customers’ details (15 per cent) and theft by customers (18 per cent). However, this research concludes that it might be difficult to estimate such losses accurately because of possible inevitable overlap of reports. Some of the survey-based estimates (e.g., Financial Fraud Action, BRC) that have been undertaken to date are likely to represent just a fraction of the individuals/retail companies surveyed. In addition, the estimated losses might be skewed upwards by extreme losses reported by a few respondents for business interests.

For instance, Financial Fraud Action UK (2014, p. 14) indicated that: “Online fraud against UK retailers totalled an estimated £105.5 million in 2013, a rise of 4 per cent on the previous year. However, there has been a substantial increase in fraud against online retailers based overseas, rising 48 per cent to an estimated £57.8 million”. This estimate of losses reported by Financial Fraud Action UK relates to just the retail sector and not the banks/payments industry, or the public. Financial Fraud Action uses only Internet-enabled CNP fraud as a measure of ‘ecommerce fraud’, but Home Office (2013) suggests that a more comprehensive report of loss estimated for the cases of internal information theft and e-commerce frauds should also include other digital payments systems, such as those from PayPal.

Other impacts reported by Kroll (2013) include outraged customers, soured B2B relationships, decrease in corporate earnings, loss of investor confidence, job losses, legal settlements, psychological issues to victims, business disruption and governmental scrutiny. Sometimes, these impacts extend to businesses (banking industry) that provide payment cards to retail customers. Reflecting on these case studies, one may expect retail companies to sack hundreds of their employees every year. But sacking the employees might not be the better option to solve internal information theft problems. Thus, the insights into these impacts of information theft cases make it very important to offer a strategic and effective prevention guide for online retail businesses.

1.10. Summary of Chapter 1

This chapter has provided a contextual understanding of internal information theft in retail business. It has answered some contextual questions of what information theft means in the retail businesses by citing some recent research and reports. Some theories in the domain of the workplace and in criminology were used to analyse the motives of internal information theft perpetrators. The analyses were extended to the knowledge of methods and opportunities used by the perpetrators. The explanation of the resulting fraud practices related to internal information theft was also provided. In addition, this chapter has provided an overview of the impacts of internal information theft by looking into case studies and reports in retail companies. The next step in this guide is about getting to know the characteristics of information theft perpetrators. Chapter 2 looks into the characteristics of perpetrators in relation to the nature of the information theft they committed, their motivation, age (at the time of the theft), gender, job title, how they were caught and lessons learnt.

Notes

1 The Anti-Phishing Working Group founded in 2003 is an international consortium of organisations (including BitDefender, Symantec, McAfee, VeriSign, VISA, IronKey, Mastercard, Internet Identity, ING Group, etc.) affected by phishing attacks (http://www.antiphishing.org)

2 Personal Identifiable Data

References

Ahuja, V. (1997). Secure Commerce on the Internet. New York: Academic Press.

Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG). (2014). ‘Phishing activity trends report: Unifying the global response to cybercrime, 1st Quarter, 2014’. Available: http://docs.apwg.org/reports/apwg_trends_report_q1_2014.pdf, Accessed 10 June 2014.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2014). ‘Report to the nations on occupational fraud and abuse: Global fraud study’. Available: http://www.acfe.com/rttn/docs/2014-report-to-nations.pdf, Accessed 20 April 2014.

Black, D. (1987). ‘The elementary forms of conflict management’, Lecture Series, School of Justice Studies, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona.

British Retail Consortium (BRC). (2013). ‘Retail crime survey’. Available: http://www.brc.org.uk/ePublications/BRC_Retail_Crime_Survey_2013/, Accessed 10 April 2014.

British Retail Consortium (BRC). (2015). BRC Retail Crime Survey 2014, Available: http://www.sbrcentre.co.uk/images/site_images/14591_BRC_Retail_Crime_Survey_2014.pdf, Accessed 19/04/2015.

Brooks, P. and Kamp, J. (1991). ‘Perceived organisational climate and employee, Counter-productivity’. Journal of Business and Psychology, 5 (4), pp. 447–458.

Burke, P.J. (2008). ‘“Identity control theory”, In: H.P. Clemens (Ed.), “Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Sociology”’. Reference Reviews, 22 (3), pp. 18–18.

Cast, A. (2003). ‘Identities and behaviour’. In: P. Burke, T. Owens, R. Serpe, and P. Thoits (Eds.), Advances in Identity Theory and Research. New York: Kluwer, pp. 42–53.

Cavoukian, A. (2013). ‘Privacy by design and the promise of SmartData’. In: Inman Harvey, Ann Cavoukian, George Tomko, Don Borrett, Hon Kwan, Dimitrios Hatzinakos (Eds.), Smart Data in Privacy Meets 1375 Evolutionary Robotics. New York: Springer, pp. 1–9.

Checkpoint. (2013). ‘Security report’. Available: http://sc1.checkpoint.com/documents/securityreport/files/assets/common/downloads/publication.pdf, Accessed 12 May 2013, pp. 4–49.

Chen, P. and Rohatgi, P. (2008). ‘IT security as risk management: A research perspective’. IBM Research Report, Thomas J. Watson Research Centre, Yorktown Heights, New York.

CIFAS: The UK’s Fraud Prevention Service. (2011). ‘Fraud trends: Fraud level surge upwards’. Available: http://www.cifas.org.uk/annualfraudtrends-jantwelve, Accessed 26 August 2013.

CIFAS: The UK’s Fraud Prevention Service. (2012). ‘Staff fraudscape: Depicting the UK’s staff fraud Landscape’. Available: https://www.cifas.org.uk/secure/contentPORT/uploads/documents/External-0-StaffFraudscape_2012.pdf

CIFAS: The UK’s Fraud Prevention Service. (2013). ‘The true cost of insider fraud, Centre for Counter Fraud Studies’, pp. 1–11. Available: https://www.cifas.org.uk/secure/contentPORT/uploads/documents/External-CIFAS-The-True-Cost-of-Internal-Fraud.pdf, Accessed 4 January 2014.

Clarke, E. (2009). ‘How secure is your client data? 5 questions you should ask your IT professionals’. Journal of Financial Planning, pp. 24–25.

Clarke, R.V. (1999). Hot Products: Understanding, Anticipating and Reducing the Demand for Stolen Goods, Police Research Series, 98. London: Home Office.

Collins J. M. (2006). Preventing Identity Theft in Your Business. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons Inc., pp. 1–256.

Cressey, R.D. (1973). ‘Other people’s money: A study in the social psychology of embezzlement’. International Review of Modern Sociology, 3 (1), pp. 114–116.

CSO Magazine. (2011). ‘Most computer related fraud is an inside job, says survey’. Available: http://www.csoonline.com/article/693649/most-fraud-is-an-inside-job-says-survey, Accessed 23 September 2011.

Davis, E.S. (2003). ‘A world wide problem on the world wide web: International responses to transnational identity theft via the Internet’. Journal of Law and Policy, 12 (1), pp. 201–227.

Dean, S., Pett, J., Holcomb, C., Roath, D. and Sharm, N. (2012). ‘Fortifying your defences: The role of internal audit in assuring data security and privacy’. PCW Publications. Available: http://www.PWC.com/us/en/risk-assurance-services/publications/internal-audit-assuring-data-security-privacy.jhtml, Accessed 9 October 2012.

Denning, D.E. and William, E.B. (2000). Hiding Crimes in Cyberspace. London: Routledge.

Ditton, J. (1977). Part-Time Crime: An Ethnography of Fiddling and Pilferage. London: Macmillan.

Douglas, M. (1970). Natural Symbols: Explanations in Cosmology. Harmsworth: Penguin.

Duffin, M., Keats, G. and Gill, M. (2006). Identity Theft in the UK: Offender and Victim Perspective. Leicester: Perpetuity Research and Consultancy International Ltd.

Fighting Retail Crime Report. (2012). Available: http://www.adderdigitalcc.tv/downloads/EmployeeTheft.pdf, Accessed 20 April 2013.

Financial Fraud Action UK. (2014). ‘Fraud the facts 2014: The definitive overview of payment industry fraud and measures to prevent it’. Available: http://www.financialfraudaction.org.uk/download.asp?file=2796.