5 Challenges in Preventing Internal Information Theft

5.1 Introduction

This chapter provides reflective knowledge for security management and contributes insights on tightening the data security processes in meeting Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) requirements. Internal information thefts have been on the rise in the last few years. The most pressing challenge, among others, is the number of dishonest employees who are indulging in internal information theft-related crimes, generally because the company board and heads of security and crime prevention are not prepared to make strategic decisions on reviewing data security frameworks in the face of tightening operation budgets. The existing data security frameworks that are designed based on the PCI DSS rules for preventing information theft were not receiving sufficient financial support. However, security managers feel that their practices have improved over time and that their employers are learning from their challenges and mistakes, and they have generally tightened up their commitment on due diligence and quality data security assurance. This can be observed in terms of how security managers monitor employees and implement data security strategies while adapting to organisational challenges.

5.2. Adoption of PCI DSS in the Prevention of Internal Information Theft

PCI DSS is the main standard and requirements set out for storing payment card data. PCI DSS specifies steps which should be taken to ensure payment card data is kept safe both during and after transactions. The current PCI DSS that guides internal information theft prevention frameworks is not as prescriptive and presented as it should be for every retail business.

The PCI DSS guidelines leave it up to an individual payment card company to design its own approaches, but it does address key issues, such as, for example, the implementation of a company’s internal and external data security run processes. It provides binding best practices on the need to contractually secure compliance by, and an acknowledgement of responsibility from, third-party providers. The PCI DSS framework does not spell out the ways in which data compliance managements can and can’t be involved in delivery and the issue of related-party transactions as clearly as it might, and that this created internal security risk. For instance, some security experts have argued that the issue of full implementation of PCI DSS leaves UK retailers “in a bit of a quandary” in relation to compliance with the Data Protection Act (DPA). This supports the Information Commissioner’s Office’s (ICO) suggestion in 2011 that UK retailers that fail to store payment data in accordance with PCI DSS “or provide equivalent protection when processing customers’ credit card details” could be held to be in breach of the DPA and subject to fines.

The view that existing security checks and controls are too broad for a retail system was common across security and crime prevention managers, mostly those managements from big retail companies’ perspectives. A common view is that the data compliance and security managements of big retail companies now have many more partner companies to oversee. For instance, in the case of UK retail, neither the PCI DSS nor any of the existing legislation covering personal data protection (e.g., Data Protection Act (DPA) 1998, Computer Misuse Act 1990, Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) Regulations 2003) is fit for the purpose of guarding against internal information theft. PCI DSS’s interest in retail is mainly contractually secure compliance to ensure payment card data is kept safe both during and after transactions. But neither it nor the security auditing firms that undertake external security audits have the capacity and skills to get below the surface to understand the relationships that are key to understanding prevention of internal information theft (will they get below the skin?).

At best, an auditor might detect data security loopholes after the internal information theft incident when the aim should be to have preventative systems: this relies too much on managements ‘within’ the retail companies at present.

The PCI DSS provides guidelines for looking at data compliance snapshots but not guidelines for security auditors. As a result, there is the potential for the scale of internal information theft cases to go unnoticed for years, as seen in the reported cases above in the Chapter 2. The fact that neither the PCI DSS nor data protection legislation is really reducing cases of internal information theft is a general challenge that the security and crime prevention management working within retail companies has to deal with.

The modus operandi of the internal information theft perpetrators seems to change day to day, so there is a sense that PCI DSS should include guides for making it up as it goes along. For instance, the PCI DSS version 3 rules that were released in August 2013 by the Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council (PCI SSC) outlined a broad timetable for when UK retailers will have to comply with the new rules. However, the majority of security and crime prevention managers seem to lead, with the PCI DSS following; managers are telling them things, including about internal information theft.

Very many security heads are spending so much time playing with software technology and experimenting with internal information theft-related crime data in different formats; they invest solely in security auditors, neglecting the roles of other functional managements and becoming distracted by software solutions and/or auditors and taking their eyes off the ball.

5.3. Overregulated and Disjointed Information Security Policies

Retail companies are already heavily regulated and scrutinised regarding information security policies for prevention of internal information theft. This oversight comes from a variety of sources: the IT security department, company data protection policy, employees’ Code of Conduct handbook, HR and internal and external auditors. The majority of existing policies and frameworks set clear rules which every employee (managers, shop-floor staff, consultants, contractors, etc.) should adhere to when accessing and dealing with companies’ personal identifiable information. The issue with various security policies is that retail companies tend to find the policies disjointed and difficult to harmonise as the companies grow. The more established retail companies work hard to tighten up their retail operation processes as they go along, generally, after a rapidly expansion; such companies would begin to struggle to cope with the demands of data compliance and regulations, which means that their security policy would not be as robust as it was early on.

Data compliance managers of large retail chains could find these issues more challenging because some of the policies may not have been clearly defined regarding security controls or operating processes. Consequently, some online retail transactions via cards are being carried out without agreed procedures for security controls. In other cases, where a large amount of operation services are outsourced to consultants and other security operating companies, these operational developments can make companies vulnerable to perpetrators of internal information theft. However, the current framework adopted by many retail companies is to assign security auditors to the outsourcing security companies run by partner small retail companies, following the decision to audit and monitor their retail operations. But with the financial capacity of some of the outsourced companies, and small size of their businesses, their level of IT security infrastructure and security capability are likely to be weak.

Even when the security auditor combines the functions of both external and internal security auditors, the auditor may be effective in the role of external security auditor and providing ‘strict’ PCI DSS rules but not effective at the regulatory function within the auditee (outsourced companies). This is not because of lack of resources but because the auditee won’t provide the security auditor with comprehensive access. Consequently, security auditors may know the extent of the security capability and can’t be confident to document the audit report. As a result, both the audit and auditee companies would be in a dilemma of either withdrawing their business contractual agreement or harmonising the security policy to provide an effective security audit.

5.4. Cultural Orientation of the Security and Crime Prevention Management

The cultural orientation of management is one of the major challenges of preventing internal information theft in retail companies. Tsai (2001) explains that cultural orientation is the degree to which employees are inclined to be actively engaged in the norms, practices and traditions of a specific organisational culture. Cameron and Quinn (1999) throw more light on the issues of culture within the organisation by defining organisational culture as a set of shared assumptions, beliefs, practices and values that direct and shape members’ behaviour and attitudes. Based on these definitions, the cultural orientation of management can be the root of other challenging issues which include: management believes that IS security is a complex issues; perception that it is difficult for companies to provide an adequate budget for IT security, internal security policies and strategies and perceived information theft incidents.

5.4.1. Complexity of Information Security

The security and crime prevention managers are inclined to treat information security regarding prevention of internal information theft as a complex organisational issue often dependent on software security. Consequently, management often resists innovative policies that might be strategic in preventing information theft-related crimes. This belief reflects the reason for Chia et al.’s (2003) argument that, without change in the cultural orientation of IS security managers, the enforcement of new policies regarding computer-related crime prevention might not be optimal.

In the same vein, the cultural orientation of the management influences retail companies’ decision to provide an adequate budget for IT security. For example, some boards of directors are inclined to treat budgets related to IT security as a financial burden to their company and are often reluctant to support information theft prevention initiatives. Instead of investing to improve their theft prevention strategies, the management relies on their managerial experience and contingency plans. This is evidenced by the analyses of the case studies that have been discussed in Chapter 2.

Crime prevention managers would be confident that they have got documented reports of all the procedures taken during the investigation; and that internal information theft happens over and over again. Managers often believe that handling criminal cases related to internal information theft provides them with enough practical experiences to help them in subsequent incidents; while professional analyses of information theft case files could cost a lot of money, take lots of times and expertise and require the hiring of professionals to do the analyses. Most of the internal information theft preventions may have failed in retail companies because of the management orientation that there is no need to invest in innovative IT security initiatives if there is no apparent security threat.

Some business organisations neglect strategic IS security practices because they have not had any major loss to computer crimes related threats. This suggestion supports the findings by PWC (2014) that more than 56 per cent of businesses did not carry out effective information security checks; instead they only relied on contingency plans.

In the same vein, PWC (2014) further added that retail companies apparently consider themselves ‘not rich enough’ to bear the cost of IS security, while other sectors often argue that the cost of IT security investment outweighs the benefits. However, some top managers point out the reason for not investing in security tools recommended by IT security managers. The reason of not investing is because the IT security managers cannot provide clear information on the substantial impact of existing IT security that have been invested in preventing internal information theft. Their argument is that IT security management is supposed to report/publish the impact of their security strategies in preventing information theft, but when this reporting is not done it is hard to evaluate the benefits of IS security investment and strategies.

In addition, the cultural orientation of the security management can weaken the security strategies in preventing internal information theft by limiting the scope of a company’s internal data security strategies and policies. In other words, the implementation of the security policies is motivated by the internal company’s requirement but not based on needs and the importance of security practices. That means that security and crime prevention management considers innovative information security strategies as worth it if they fit into the policy stipulation of their company. Maynard and Ruighaver (2006) suggest that, in most cases, due to the organisational security culture, a number of business organisations are forced to conform to existing internal information compliance and security policy not because the policy is worthwhile but because it fits into their orientation.

5.4.2. Narrowly Defined Security Roles

Similarly, the issue of cultural orientation has some impacts on the responsibilities of security managers in relation to their peculiar job roles. For instance, in the case when the security managers are explicitly empowered to intervene and make independent decisions in order to address poorly designed data security tools and policies, this can be used against them if the decisions are not statutorily meant to be within the their defined job responsibility. Software engineers always continue with their major job roles, which is basically designing retail company system applications, but they neglect the need to contribute to improving internal information security—which the software engineer would argue is a role that should be left to the security and top managers to handle.

This is the case in some retail companies, where managers have to stick to their job roles with little or no contribution to the collaborative effort regarding internal data security and internal information theft prevention. Top security and crime management are saddled with roles of designing and implementing security strategies in preventing information theft-related crimes, while the shop-floor employees see internal data security regulations prevention as the business of the top management alone. However, Popa and Doinea (2007) argue that the perceived cultural orientation where only the top managers are concerned with issues of internal information theft prevention might be linked to the reason that internal information theft is a sensitive security issue as well as the complex nature of these crimes. This reason can be considerable, as some businesses managers often do not trust the capabilities of shop-floor employees because complex security practices require the expertise of top data security management. In a similar suggestion, Koh et al. (2005) added that, because of the nature of IS security, only a fraction of management is involved in implementing security strategies, and this could pose a major challenge in business organisations.

5.4.3. Classification of Information Theft Incidents

Some security management personnel believe that the amount of attention that would be given to a particular information theft incident would depend on the nature and the class of the incidents. This issue of incidents’ characteristics and classification was discussed in Chapter 2 as it has influence on the amount of effort the law enforcement agency/police put into information theft investigations. In the same vein, security management believes that some incidents should be treated with respect to the characteristics of an internal information theft incident profile—who the perpetrator is, where the perpetrator comes from and what is the perpetrator’s ethnic origin. The IS security management is inclined to think that some employees with some cultural features are more prone to perpetrating internal information theft than others.

Because of cultural influence in the way the IS security management investigates information theft incidents, some of the incidents are not given due attention because the suspect is from a developed country or belongs to an ethnic majorities. Some members of crime investigation teams would argue that most internal information theft-related crimes they have investigated are perpetrated by employees from minority ethnic groups, although sometimes there are bad ones from developed countries, but the cases from developed countries are not that bad compared to those from those minorities.

The crime prevention managers seemed to believe that employees from ‘developing’ or ‘less developed’ countries are more likely to perpetrate crimes than those from developed countries. Drawing upon this insight, that security and crime prevention management holds a biased view of law-abiding employees from minority ethnic background, Westley (1970) has explained that security officers (within the occupational roles of control) often experience hostility in the environment of ethnic minority as they perceive such environment to be prone to crimes.

In a similar study, Skolnick (1966) explains that security officers respond to crime incidents in a way that predicts the situations and perpetrators which present the greatest risk to security management. Skolnick (1966) suggests that security officers refer to such perpetrators as the ‘symbolic assailant’, which means a profile of an individual whose appearance, ethnic background and demeanour represents an indicator of criminal behaviour, irrespective of whether the individual actually commits crimes. Having this occupational culture, Cosgrove (2011) argues that security officers are inclined to be suspicious in identifying abnormal crime-related activities. In doing so, security officers gather information on innocent individuals which officers may have assumed to be at the risk of offending in a way that satisfies the perception of the symbolic assailant.

Other earlier studies (e.g., Westley, 1970; Cain, 1973; Waddington, 1999; Scerra, 2011) refer to this perception as a culture of ‘racial and ethnic minorities prejudice’ which is common not only in the police occupation but also in other related crime prevention settings.

5.5. Stereotyped Attitudes of Security and Crime Prevention Management

In particular, Scerra (2011) characterises the cultural orientation of crime prevention managers as ‘investigating stereotypes’, where the crime prevention managers use stereotypes in dealing with their roles, functions and practices. This issue has also been noted by Sanders and Young (2003), who point out that the cultural orientation of police work in the UK affects the way police label suspects based on their race and subsequent group. The suspects who fall within marginalised groups in society are often vulnerable to prosecution even when they are not guilty (Engel et al., 2002). However, this book cannot fully provide answers to the question of why IS security and crime prevention managers act the way they do without considering the meaning that managers ascribe to their actions and the retail business environments.

IS security and crime prevention management personnel are multicultural professionals from multifaceted backgrounds. Newburn and Webb (1999) argue that the issue of cultural orientation is synonymous with challenges commonly experienced by security managers in preventing business or corporate crimes. Newburn and Webb suggest that one of the major factors that encourages the cultural perception of management in the prevention of crimes is the high degree of internal solidarity and secrecy within the security management. Newburn and Webb (1999) further added that any attempt to curb this influence in business organisations results in cynicism and displeasure. Similarly, Paoline (2003) argues that crime prevention managers develop culturally oriented attitudes, norms and values in relation to their occupation as a means of adapting to the demand of their work and also as a means to cope with the scrutiny of their organisational environment.

Moreover, McConville and Shepherd (1992) discussed cultural orientation regarding security management as an occupational issue which is common in crime prevention settings.

McConville and Shepherd argued that what some lower-level and shop-floor crime prevention managers learn in their occupation is the need to keep their mouths shut about unethical security practices, including those in breach of the security compliance rules, which experienced managers deem necessary in discharging their security management roles and responsibilities. In doing this, Reiner (1992, p. 93) argues that crime prevention managers across all levels tend to adopt secrecy as ‘a protective armour shielding them from public knowledge of ‘culturally oriented unethical security’ infractions’. And as Newburn and Webb (1999) pointed out earlier, it is not just about secrecy, but about the organisational or occupational level of bureaucracy.

Newburn and Webb added strong bond of loyalty, rated integrity of leadership as other vital features that characterised security professional.

Other sociological studies (e.g.,Van Maanen, 1974; Manning, 1989) argue that crime prevention managers form culturally oriented unethical security attitudes, beliefs and values due to their rampant experiences of the challenges associated with their occupation of crime prevention. These studies suggest that those working in a crime prevention setting with limited cultural training and a remit for reassurance are likely to be overwhelmed by the strains associated with crimes prevention. Manning (1989) suggests that there is a link between culture and security practices, which is a huge challenge to security management. This suggestion calls for security managers to watch out for ‘contours of the impact of the culture in crimes prevention’, especially investigating those aspects of the occupational security cultures undermining compliance with rules/regulations. Slapper and Tombs (1999) argue that preventing corporate business related crimes requires examining the crimes inwardly in terms of organisational culture. Organisations present moral values, which can symbolise the specific organisational identities of their management and employees.

5.6. Negligence of Security Challenges by Retail Management

The implication of cultural influence could nurture the perception of management negligence, which can have a significant impact on prevention of information theft. The culturally oriented unethical practices within the crime prevention management culture has been identified in several reports/inquiries (e.g., Criminal Justice System) as both encouraging inefficiency and hampering security strategies and management efforts in crime prevention (Newburn and Webb, 1999).

Fitzgerald (2007) extends and links the causes of these cultural issues to wider crime prevention challenges which include: inadequacy of educational training of the security managers (especially with regard to culturally oriented unethical security training); abuse of management authority, inadequacy of crime prevention management or poor security management; disregard for honesty and the truth in criminal investigations; contemptuous attitude toward the criminal justice system on the part of the crime prevention manager and rejection of criminal justice system application to crimes prevention.

Moreover, Roukis (2006) suggests that lack of emphasis on the intentions of employees towards ethical security practices could lead to the absence of organisational transparency. Lack of transparent security practices of management can produce criminal behaviour, especially when there are occupational challenges and work pressures are hard on the security management. Roukis (2006) further added that, in the highly challenging occupational environment of crime prevention, a security manager might be tempted to commit internal information theft-related crimes such as thefts of intellectual property, fraudulent manipulation of company stocks and paying bribe to business contractors. Roukis recommends that it is vital to get rid of ambiguity within business environments and to foster cultural-oriented managerial transparency where defined ethical practices are a corporate priority.

In support of Roukis’s (2006) recommendation, other researchers (e.g., London, 1999; Dion, 2008) suggest that a ‘principled leadership’ could be the way for security managers to apply clearly defined culturally oriented ethical business values in their occupational life, such as fairness, honesty, kindness and mutual respect. With principled management integrated with moral courage (use of inner principles to do good regardless of the personal risks), Sekerka and Bagozzi (2007) suggest, managers would be able to make security decisions ‘in the light of what is good’ for cross-functional management despite personal risks of cultural orientation. Punch (1994) suggests that the impact of cultural orientation on crime prevention can be removed by taking the authority to make decisions out of the hands of top managers. The Criminal Justice Commisssion (1997) recommends that cultural influences can also be reduced by rotating on a regular basis the roles of security managers in ‘high risk’ or sensitive areas.

5.7. Law Enforcement Agency and Police Indifference

Police indifference is one of the major challenges that affect the security and crime prevention management’s effort in preventing internal information theft. This attitude of indifference is rooted in the perception by the police that there are locations or business sectors where crimes are believed to be more prevalent than others. For instance, in the UK, crime reports from cities such as London, Birmingham, Manchester and Glasgow are given priority by the police response team because the cities are seen as sites of notoriety for crimes. If internal information theft incidents reported to the police fell outside these cities, then the police would treat the incidents as ‘non-serious’ cases. Berki (1986) refers to this kind of indifference from formal state security officers as ‘malevolent indifference’, which can contribute to feelings of insecurity not only on the part of citizens (retail customers) but also on the part of businesses.

Berki (1986, p. 11) explains further that indifference is the disregard meted out to citizens with implied feeling and intention that their interests, desires and security should not count at all and should not be treated in the same way as those of other citizens. This perception that crime reports from smaller cities or small business sectors are disregarded is affecting the police contribution in preventing internal information theft in retail companies. This issue of indifferences in some cases is a misconception, which often leads to negligence on the part of management efforts in preventing internal information theft in online retail (Prenzler, 2009).

This misconception may interfere in some ways with how the law enforcement agency views the crimes in society, which may lead to crime cases from the small cities being neglected to the detriment of the businesses in those cities. Consequently, the incidents of information theft may continue to increase in retail companies unless police change their attitude of indifference to crime investigation and give equal attention to every crime irrespective of the cities or the sectors where the crimes were committed, whether they are high-profile crimes or low-profile crimes.

Police are overwhelmed with the perception that because other crimes are rampant in bigger cities, so too is internal information theft. This perception points to the reason the police believe that information theft-related crimes can be tackled like any other crime. Researchers (e.g., Flanagan, 2008; Rix et al., 2009) argue that police rarely cooperate in investigating information thefts because these crimes emerge from the retail sector, which is a small sector compared to the banking sector. In addition, Ashworth (2005) notes that police would rather get themselves involved with high value or violent crimes. Bamfield (2012) agrees with Ashworth (2005) and argues that although retail crimes such as internal information theft might be important to the police, they may not be one of the top priorities central to their crime prevention strategies and to the policies of police headquarters.

The issue of police indifference in cooperating with retail management in combating information theft might leave the management open to potential litigation for unlawful arrest. This might be the case if a suspected perpetrator was arrested without police cooperation and held for somewhat too long.

The issue of lack of interest shown by police in investigating information theft creates a serious challenge for security managers in retail companies. Walker et al. (2009) argues that police indifference in cooperating with retail managers in combating information theft has greater impact on business organisation than the loss of their business assets. However, Bamfield (2012) suggests that the issue of police indifference lingers in retail companies because the police often criticise retailers’ crime prevention policies. In particular, the prevention of crimes (as the case of retail companies) requires specific crime prevention policy changes for retailers to receive substantial police cooperation. This suggestion by Bamfield (2012) supports Seneviratne’s (2004) arguments that police should be liable to their own decision whether to adopt a particular policy or prosecute a perpetrator. And that it is the responsibility of police to post their men to crime incidents, but in whatever crime detection and prosecution, police are not servants to anyone, except for the law itself.

Interestingly, these arguments tend to defend police indifference in investigating crimes and also point to the reason behind the attitude of the police regarding their indifference in preventing information theft. In addition, Bamfield (2012) suggests that other issues, such as individual decisions, corporate culture and operational shortages, may contribute to police indifference in preventing information theft in retail companies.

Retail companies are not alone in facing the challenge of police indifference in their effort to prevent information theft.

The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) in their 2010 report (A Frontline Force: Proposals for More Effective Policing) suggests that there are concerns about police inefficiency in crime prevention across business sectors. The concerns are worsened by other related issues such as police costs, weak strategic police leadership, inefficiency in their organisational structure and complexity of dealing with crime investigation where police spend lots of time dealing with minor crime cases (Carter, 2003; CBI, 2010; Berry et al., 2011). The Home Office (2011) policy statement (A New Approach to Crimes) raised similar concerns about police indifference in preventing crimes.

Comparatively, the CBI’s report and the Home Office’s policy statements seem to defend the ways things are being done in the police. They argue that the issues of inefficiency and bureaucracy in particular within the police contribute to their attitude of indifference towards crime prevention. Notwithstanding that bureaucracy exists in every institution that deals with crimes (Bamfield, 2012), it is vital that police should have specific ways of dealing with information theft in retail companies. There should be a procedure agreed upon by both retail management and police to minimise the issues of bureaucracy in investigating and prosecuting the internal information theft perpetrators.

Provision of clear roles and responsibilities between the police and retail management would reduce the brick wall that might be encountered by the police during investigation. Clarifying the role of both parties would reduce the amount of time spent on particular information theft incidents. For instance, it could reduce the amount of paperwork regarding internal information theft incidents and witness reports. Consequently, clarifying the roles of the police would reduce the bureaucracy that might have given birth to indifference, which may curb the impact of the internal information in the retail companies. However, this suggestion would work effectively only if there are existing relationships and collaboration between a retail company and the local police. Retail management needs to work collaboratively with the local police. Another option that would change the police indifference in preventing information thefts is to establish a system where the retail security officers and police would work together. This kind of system (Project Griffin) was initiated in the case of counter-terrorism where police, business and the private sector security, emergency services and local authorities coordinate to protect UK cities from terrorism (Confederation of European Security Services (CoESS), 2012). There should be police enlistment of retail security officers to enable the retail security management to work collaboratively with them in protecting retail information systems while preventing internal information theft.

Such collaboration ingrained with good relationships would enable the police to understand retail operations, reduce the potential investigation bureaucracy and thus change police indifference in preventing information theft in retail companies.

5.8. Other-Related Challenges in Preventing Internal Information Theft

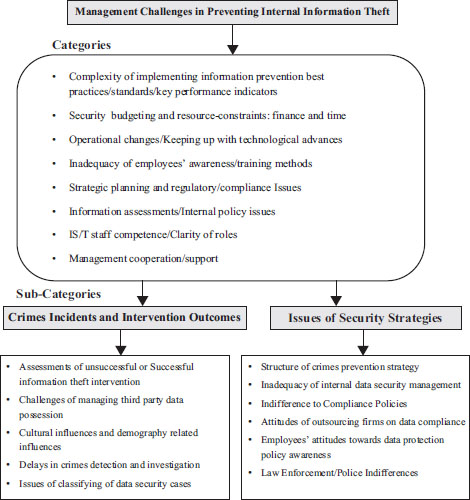

Both large and small retail companies have most of these key challenges that have been discussed above. Other related challenges are summarised in Figure 5.1 below. The challenges in the upper category of the figure represent the challenges that are recognised as the key issues. These challenges have been the most problematic issues because the demands are much greater for security and crime prevention management in both small and larger retail companies. Comprehensive knowledge of these challenges would provide managers with the right information to make strategies for internal information theft prevention that would be accountable for security/compliance investment probity. These challenges include but are not limited to:

- Clarity of roles

- Management cooperation/support

- Operational changes

- Lack of employees/end-user awareness training

- Lack of clarity of data protection policy

- Lack of trained IS/T staff

- Complexity of internal information theft incidents

- Poor IS/T security tools

- Poor internal data security control and strategy

- Management attitudes towards information theft intervention outcomes

Clarity of Roles: Security and crime prevention management are not clear with the commitment required of them in prevention of internal information theft, although a few pay attention in identifying the vulnerability by classifying the data security cases. Without clear responsibility, the overall internal information theft prevention and internal data security strategies are handicapped. Management should be reflective of what their key roles and responsibilities are in relation to internal information theft prevention. Their roles should not be limited to being busy with routine information theft escalation processes: detection, investigation, etc. They should be more committed to meeting their targets of completing investigation cases while reflecting on the requirement of their job roles.

Management Cooperation/Support: The crime prevention management has difficulty in building effective working relationships with the management of the cross-functional management and local law enforcement agency. This could lead to delays during the crime investigation. Without efficient support between retail management and law enforcement agencies, there may be cases of protracted internal information theft investigations.

The longer the investigation, the more damage the perpetrators would do with the stolen data/information. However, this challenge could be linked to the complex nature of information theft incidents. It is difficult to collaborate with management across businesses and departments when dealing with information theft investigations. Even when implementing best security practices, many retail companies’ security managers find it daunting to get support and collaboration of management; it is hard to monitor the best practices across many collaborators because of inter-agency restrictions/policies and privacy-related issues. This is one of the greatest areas of risk for implementing best practices to prevent internal information theft in the context of collaborative management requirements.

Operational changes: There is concern about the issue of operational changes (such as reduction in IT security budgets and shuffling of staff management positions) and the impact on internal information theft prevention in retail companies. This issue is beyond the capability of some security and crime prevention managers. For this reason, they utilise the resources they have at their disposal to implement the latest security tool for prevention of the information theft. The challenge of operational changes in retail companies can lead to other implications, which include the budget constraints, the employees’ expertise, and pace of the evolving digital security technologies. For instance, a new security head in some retail companies may argue that deploying and implementing up-to-date security tools is not cheap, insinuating that business owners should spend less. In doing so, the new security manager would be applauded or be recognised for being decisive in his or her spending.

Lack of Employees/End-User Awareness Training: The effort by the management toward training of the employees is established with independent capability in most retail companies. It is either carried out by the human resources or never gets done. In some cases, the attempts to educate all the employees have not yielded the expected result. This setback in employee awareness training on the prevention of internal information theft may be associated with the cost of human resource development.

Moreover, most of the available data security policies are not clear enough to the level of understanding of the shop-floor employees. Even when some retail companies have mandatory e-learning (data protection policy and regulations) that is designed to meet the educational requirements and levels of all management and employees, it may not be. But is this achievable considering the financial implications and other related challenges?

Lack of clarity of data protection policy: Lack of well-defined policy in retail companies makes it difficult for outsourcing companies to effectively contribute to information theft prevention. Some third-party companies rarely buy in or adhere to the stipulated data security agreement. They handle internal data security with laxity. In most cases, they do not put in place the security checks and measures to avoid any accidental data leakages or theft that might arise during transactions. In some cases, outsourced companies only tick the papers to prove that all the data security checks are up to date, because they never see this as their responsibility—they see it as the responsibility of outsourcing companies to ensure that the data transaction channels are secure. However, where the outsourced companies are not abiding by the data protection policy, most outsourcing companies have resorted to the strategy of coercion and thorough data security auditing. If these strategies failed, outsourcing companies would revoke their business contract with the outsourcing firms. This challenge, in turn, leads to the implication that some retail companies may not have adequate staff expertise and resources for prevention of information theft, and that is the reason for outsourcing security support.

Lack of trained IS/T staff: The instances where the retail companies have to consult outsourcing companies suggest that most of them cannot provide the necessary staff expertise and resources for preventing internal information theft. The practice of outsourcing or hiring an external agent in retail companies may have strained the management effort in establishing the effective cooperation and sharing of responsibilities in regarding effective internal information prevention. This issue extends to other factors in relation to lack of effective communication and role sharing with other complementary management, such as law enforcement agencies. As noted above, the lax attitudes of the outsourcing and law enforcement management in cooperating with retail companies is a major setback. In some cases, outsourced companies’ management does not have good knowledge of data security in carrying out their responsibilities in the prevention of internal information theft.

This challenge can lead to delays in information theft investigation protocols because of role clarifications issues, such as ‘who does what and where do we go first’, in the case of internal data security breaches.

Complexity of internal information theft incidents: The complexities of internal information theft incidents, such as the ‘seriousness’ of the crime, culture, and the outcome of a crime incident, interfere with security strategies. On the issue of incident assessment and interventions, the management often depends on an after-the-fact assessment of intervention processes of typical incidents. They also believe that their experience helped them in designing effective and improved data security strategies. Some information theft interventions may have failed in retail companies because of management that was overly dependent on their experiences in handling their complexities.

Poor IS/T security tools: There are cases in retail companies where security loopholes were discovered within the IT platform and were neglected because management viewed it as not being cost effective to upgrade or as not constituting a high risk. The incidents are rated from high-risk issues to low-risk issues. Perception like this affects the roles of the data security expert in the design of the data security tools, like encryptions for the security of such data.

Poor internal data security control and strategy: Among the top IT security and crime prevention teams, internal data security should be their prime responsibility, but the attitudes of management in retail companies, in some cases, are in a poor state. Although management receives support from cross-management (e.g., HR, software engineering and network/web administrators), there is no collaborative strategy. This issue has led cross-functional teams to place a lot of emphasis on abiding by data security policies but to neglect the key aspect of IT security, which is internal security control.

5.9. Summary of Chapter 5

This chapter has provided insight into challenges that require management attention in the prevention of internal information theft. The challenges vary, as they relate to the complexity of security, the indifference of law enforcement agencies, the cultural orientation of crime prevention managers, and so on. These varying issues weaken implementation of data security strategies in preventing internal information theft. On the other hand, other challenges are interrelated in such a way that one challenge often leads to another. For instance, training of employees is very difficult to achieve in retail companies because of the time and cost. Retail companies may have incentives to invest significant resources in training their IT security and crime prevention employees, but budget constraints and operational changes are still the challenge to deal with.

As a result, they continue to adopt coercive data security approaches which pay off on a short-term basis. However, while internal information theft prevention issues may be an extreme case, the challenges discussed above cannot be considered completely representative or exhaustive prevention challenges faced by management in the retail sector. The purpose of this chapter is not to identify and provide a complete list of internal information theft prevention challenges in retail companies. It is, rather, a guide that can be used as a reference for readers.

To investigate how management can minimise the impact of these prevention challenges, Chapter 6 explores how a strategy of collaborative security management can be effectively deployed in retail companies.

References

Ashworth, A. (2005). Sentencing and Criminal Justice (4th edn.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bamfield, J. (2012). Shopping and Crime: The Police and Retail Crime. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 180–192.

Berki, R.N. (1986). Security and Society: Reflections on Law, Order and Politics. London: J.M. Dent, pp. 11–14.

Berry, G., Briggs P., Erol, R. and van Staden, L. (2011). The Effectiveness of Partnership Working in a Crime and Disorder Context: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. Research Report 52. London: The Home Office.

Cain, M. (1973). Society and the Policeman’s Role. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Cameron, K.S. and Quinn, R.E. (1999). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Carter, P. (2003). Managing Offenders, Reducing Crime: A New Approach. London: Home Office.

Chia, P.A., Maynard, S.B. and Ruighaver, A.B. (2003). ‘Understanding organisational security culture’. In: M.G. Hunter and K.K. Dhanda (Eds.), Information Systems: The Challenges of Theory and Practice, Las Vegas, USA: Information Institute. Available: http://people.eng.unimelb.edu.au/seanbm/research/PacisChiaRuighaverMaynard.pdf.

Confederation of British Industry (CBI). (2010). ‘A frontline force: Proposals for more effective policing’. CBI Report on Public Services, pp. 1–23.

Confederation of European Security Services (CoESS). (2012). Critical Infrastructure Security and Protection—The Private–Public Opportunity. Paper and Guidelines by CoESS and Its Working Committee on Critical Infrastructure Protection, May.

Cosgrove, F.M. (2011). An Appreciative Ethnography of PCSOs in a Northern City. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University.

Criminal Justice Commission. (1997). Integrity in the Queensland Police Service: Implementation and Impact of the Fitzgerald Inquiry Reform. Brisbane, Australia: Criminal Justice Commission.

Dion, M. (2008). ‘Ethical leadership and crime prevention in the organizational setting’. Journal of Financial Crime, 15 (3), pp. 308–319.

Engel, R.S., Calnon, J.M. and Bernard, T.J. (2002). ‘Theory and racial profiling: Shortcomings and future directions in research’. Justice Quarterly, 19, pp. 249–273.

Fitzgerald, T. (2007). ‘Building management commitment through security councils, or security council critical success factors’. In H. F. Tipton (Ed.), Information Security Management Handbook. Hoboken, NJ: Auerbach Publications, pp. 105–121.

Flanagan, R. (2008). ‘The review of policing’. Final Report, pp. 1–5.

Koh, Ruighaver, A.B., Maynard, S.B. and Ahmad, A. (2005). ‘Security governance: Its impact on security culture’. Proceedings of 3rd Australian Information Security Management Conference, pp. 47–56.

London, M. (1999). ‘Principled leadership and business diplomacy: A practical, values-based direction for management development’. The Journal of Management Development, 18 (2), pp. 170–89.

Manning, P.K. (1989). ‘Occupational culture’. In W.G. Bayley (Ed.), The Encyclopaedia of Police Science. New York: Garfield, p. 362.

Manning, P.K. (1995). ‘The study of policing’. Policing and Society, 8 (1), pp. 23–43.

Maynard, S.B. and Ruighaver, A.B. (2006). ‘What makes a good information security policy: A preliminary framework for evaluating security policy quality’. Proceedings of the fifth annual security conference, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA.

McConville, M. and Shepherd, D. (1992). Watching Police, Watching Communities. London: Routledge.

Newburn, T. and Webb, B. (1999). ‘Understanding and preventing police corruption: Lessons from the literature’, Home Office Policing and Reducing Crime Unit Research and Reducing Crime Unit. Police Research Series, pp. 1–45.

Paoline, E.A. (2003). ‘Taking stock: Toward a richer understanding of police culture’. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31 (2003), pp. 199–214.

Popa, M. and Doinea, M. (2007). ‘Audit characteristics for information systems’. Revista Informatica Economic, 4 (44), pp. 103–106.

Prenzler, T. (2009). Police Corruption: Preventing Misconduct and Maintaining Integrity: Advance in Police Theory and Practice Series (2nd edn.). CRC Press; Taylor and Francis, pp. 15–25. Available: https://www.crcpress.com/Police-Corruption-Preventing-Misconduct-and-Maintaining-Integrity/Prenzler/9781420077964.

PriceWaterCoopers (PWC). (2014). ‘Information Security Breach Survey (ISBS) technical report’. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/307296/bis-14–767-information-security-breaches-survey-2014-technical-report-revision1.pdf, Accessed 2 April 2014.

Punch, M. (1996). Dirty Business: Exploring Corporate Misconduct. London: Sage.

Reiner, R. (1992). The Politics of the Police. Hemel Hempstead, UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Rix, A., Joshua, F. and Maguire, M. (2009). Improving Public Confidence in the Police: A Review of the Evidence (2nd edn.). Home Office Research Report 28. London: Home Office, pp. 1–4.

Roukis, G.S. (2006). ‘Globalisation, organizational opaqueness, and conspiracy’. Journal of Management Development, 25 (10), pp. 970–980.

Sanders, A. and Young, R. (2003). ‘Police powers’ in: T. Newburn (Ed.), Handbook of Policing. Cullompton, UK: Willan Publishing, pp. 281–312.

Scerra, N. (2011). ‘Impact of police cultural knowledge on violent serial crime investigation’. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 34 (1), pp. 83–96.

Sekerka, L.E. and Bagozzi, R.P. (2007). ‘Moral courage in the workplace: moving to and from the desire and decision to act’. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16 (2), pp. 132–149.

Seneviratne, M. (2004). ‘Policing the police in the United Kingdom’. Policing & Society, 14 (4), pp. 329–347.

Skolnick, J. (1966). Justice Without Trial: Law Enforcement in Democratic Society. New York: Macmillan College Division.

Slapper, G. and Tombs, S. (1999). Corporate Crime. Harlow: Longman Criminology Series, Pearson Education Ltd.

Tsai, J.L. (2001). ‘Cultural orientation of Hmong young adults’. Journal of Human Behaviour and the Social Environment, 3 (4), pp. 99–114.

Van Maanen, J. (1974). ‘Working the street: A developmental view of police behaviour’. In H. Jacob (Ed.), The Potential for Reform of Criminal Justice. Sage Criminal Justice System Annual Review, 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Waddington, P.A.J. (1999a). Policing Citizens: Authority and Rights. London: Routledge.

Westley, W. (1970). Violence and the Police. Cambridge, MA: The Free Press.