9 Recommended Practices for Internal Information Theft Prevention

9.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses recommended security practices garnered from renowned IS security consulting firms and research experts. Information security strategies are practices that ensure that employees do not steal and leak sensitive/critical retail business information. The strategies include software products that can help security professionals control what information employees can process during retail operation.

Although adoption of rigorous security strategies is very important, the effectiveness of strategies in preventing internal information theft depends on these practices: security of employees, implementing internal proprietary security/control, well-defined corporate policies and information security audits. This chapter helps the reader to understand the importance of these practices in the prevention of internal information theft through an in-depth analysis of multiple case studies, reports and recommendations.

9.2 Security Practices for Internal Information Theft Prevention

Vulnerabilities and Patch Management are among the top five security strategies recommended for the prevention of internal information theft. Retail companies should ensure that vulnerability and patch management of security software are maintained and updated. This suggests that vulnerabilities management is an essential data security tool and that maintenance should be the core statistic of a security metric for any business IS security. Along with vulnerability management, code and configuration reviews were suggested as elements that need to be given priority in patch and vulnerability management.

Other security strategies that are suggested by the firms are Application and Data Security, threat identification focused on Internal Human Threats, Controlled Access Based on the Need to Know and User Security Training and Awareness. In particular, User Security Training and Awareness, threat identification focused on Internal Human Threats and Controlled Access Based on the Need to Know were also given a high level of priority, as these are directly related to end-user and human roles in retail businesses.

Microsoft’s Enhanced Mitigation Experience Toolkit (EMET) suggests that IS managers should focus on finding specific internal information theft vulnerabilities, and it blocks potential security exploits (TechNet Blogs, 2013). SANS Critical Security Controls, (2008) suggests that conventional information theft prevention based on data security certainly has its place, although the success of the prevention strategies depends mostly on how the IS security management implements them.

Other suggestions, like the Kill-chain approach (KCA) suggested by Lockheed and Hutchin (2010), essentially recommend the integration of both technology and human roles in mitigation approaches, with much emphasis on the process of implementation as the key linked to KCA success.

Table 9.1 summarises the internal information prevention strategies according to the priority that should be given in implementing them. This priority is suggested by case reports by the Forrester Seeburger (2013). They are arranged in decreasing order of the priority that they should be given by companies.

Other strategies recommended by Forrester Seeburger Security and the Consortium for Cyber Security Action include: complementing the business security required with business partners/third parties; integrating physical and logical security; e-Discovery; engaging law enforcement agencies; security outsourcing; complying with security requirements placed upon businesses by their partners; limitations and control of network ports, protocols, and services; controlled use of administrative privileges; boundary defence; maintenance, monitoring, and analysis of security audit; Controlled Access Based on the Need to Know; account monitoring and control; data loss prevention; incident response and management, and secure network engineering

9.3 Practices for Internal Information Theft Prevention

Information process risk assessment and training of employees to recognise bogus information processing and applications (credit card, bank account) have proven to be one of the top security strategies in preventing information theft. Most security consultants agree that retail companies that adhere to the practices of effective data protection and compliance management often succeed in preventing information theft. The UK Data Protection Act of 1984 and 1998 and the Information Commissioner’s Office provide the guidelines for internal information theft prevention through effective protection of customer data, a thorough employee recruitment process, and secure record management, effective monitoring of employees, and structured training of employees on information theft awareness. However, it is important to note that the success of these guidelines is reliant on the readiness of retail management to effectively implement them. The following sections summarise information theft prevention practices, although not the exhaustive lists of the practices.

|

Priority |

Forrester Seeburger Security |

Consortium for Cyber security Action |

Global Information Assurance and Data Security Essentials |

||

|

1 |

Data Security |

Inventory of Authorised and Unauthorised Devices |

System Characterisation and defining the scope and boundaries IS |

||

|

2 |

Managing vulnerability and threats |

Inventory of Authorised and Unauthorised Software |

Threat Identification focused on Internal Human Threats |

||

|

3 |

Business continuity/disaster recovery |

Secure Configurations for Hardware and Software on Laptops, Workstations, and Servers |

Vulnerability Identification in Information Systems |

||

|

4 |

Managing information risk |

Continuous Vulnerability Assessment and Remediation |

Control Analysis and Review of Data Security Controls |

||

|

5 |

Application security |

Malware Defences |

Likelihood Determination of possible Exploit/Vulnerability |

||

|

6 |

Aligning IT security with the business |

Application software security |

Impact analysis |

||

|

7 |

Regulatory compliance |

Wireless Device Control |

Risk determination of exposure to information theft (low, medium, high) |

||

|

8 |

Cutting costs and /or increasing efficiency |

Data Recovery Capability |

Results, documentation and process presentation |

||

|

9 |

Identity and access management |

Security skills assessment and appropriate training to fill gaps |

Data security control recommendations |

||

|

10 |

User security training and awareness |

Secure configurations for network devices such as firewalls, routers, and switches |

Penetration Test |

9.3.1 Security of Critical Retail Business Assets

The security of critical retail business assets, partly discussed in Chapter 2, is very important. The effective security of the key business assets—people and property—can immensely enhance effective prevention of internal information theft in retail businesses.

People: Security of Employees

Awareness of mechanisms for stealing information within retail business creates a sense of confidence in the employees and equips them with knowledge to prevent information theft risks. The UK Credit Industry Fraud Avoidance System (CIFAS) has suggested that employee awareness of collusion, coercion and collaboration is one of the most effective prevention practices for information theft.

In addition, good reporting procedures for information theft cases/incidents rebuild employee confidence that such cases would be handled according to the business ethics of their organisations. Three major practices have been commonly adopted by businesses to complement the security of employees: vetting and screening of employees, staff monitoring, and staff profiling.

Vetting and Screening of Employees: Background screening of current or potential employees is a first line of security in the prevention of internal information theft. Effective screening can reduce the risks associated with retail businesses employing potentially dishonest employees. CIFAS’s ‘Enemy Within’ suggests that lack of checks and controls during recruitment increases the risks of employing dishonest employees that may pose internal information theft risks. Thorough recruitments checks and controls do not only identify the dishonest staff prone to committing internal information theft and related fraud but also prevent the infiltration of the employees alike. These findings suggest the need for the relentless effort of personnel managers in vetting processes in many retail companies. If the fight against internal information theft related crimes is ever going to succeed, prospective employers must ensure the credible vetting of all new employees.

Staff Monitoring: This is monitoring of employees through human resources (HR) and promotion of the internal corporate culture of employees. Companies with a good tradition of internal HR management have fewer cases of internal information theft compared to those without. Businesses invest a lot of resources to secure their IS infrastructure from external attack sources like hackers but neglect the threat posed by dishonest employees. HR management can promote effective monitoring of the employees who are living a suspicious lifestyle that may pose potential threats to the business.

HR managers can create a desirable culture in every organisation by promoting: fraud management policy, employee fraud prevention policy, code of conduct or business ethics, disciplinary policy, fraud reporting policy, whistleblowing policy, staff assistance policy and fraud specialist policy. It is important for businesses to set standards of employees’ information processing culture/conducts, which should be monitored, and effectively guided by the information protection policies. Although legal action against dishonest employees and fraudsters based on the business policy might be expensive, it still serves as deterrence for potential perpetrators and their collaborators.

Case Study 9.1 Information Theft Risks Associated with Recruitment

UK Fraud Advisory Panel (2011) reports that the majority of potential employees lie in their job applications. In their report, it was indicated that 25 per cent of the curriculum vitae of the applicants examined were falsified with information related to academic qualifications and employment histories to secure their potential employment. This report also recorded that 34 per cent of managers failed to check the background of their prospective employees. Of all companies that were surveyed by the Chartered Institute of Personnel Development (CIPD) cited in Hinds (2007), only 77 per cent of the companies crosscheck their potential candidate references. One may argue that the remaining 23 per cent is smaller compared to the 77 per cent, but this could do much more damage to any organisation, considering the impact of internal information theft.

Staff Profiling: This is a technique of developing a behavioural pattern of an information theft suspect. Profiling can encourage effective risk analysis and paves the way for thorough investigation, and the outcome can be used as a guide for changing information security strategies and amending policies within organisations. Profiling helps businesses to establish which job roles or business areas pose the most information theft risks and enables the intelligence services to design predictive modelling tools.

9.3.2. Security of Proprietary Information Systems

Retail companies should invest more on security systems and controls to avoid being targeted as the weakest link. The advancement of the information technology has enabled information theft perpetrators to continue to refine and update their techniques. For instance, the recent 2011 Sony PlayStation Network (PSN) attack remained a lesson for the business organisation that thorough and updated proprietary information security is indispensable for internal information security. If PSN was thoroughly subjected to internal data and proprietary security and other rigorous intrusion detection control tests, perhaps, the compromise of the about 70 million users’ personal identifiable information would have been averted. Although there is still evidence that the cause of the PSN attack was linked to a dishonest act within the company, the need for effective internal data proprietary security monitoring remains obvious. Cases of internal information theft, as presented in Case Study 9.2, are still rampant because of the security loopholes of the IT infrastructures and proprietary systems. However, some of the new complex technologies that have been noted to have proven security for process, property and proprietary information security are biometric technologies, cryptography, authentication and certification and single-sign on technologies.

Although some of these leading data security technology solutions—IBM AppScan, forensic data warehousing, Vontu by Symantec—exist, companies might not make much out these security tools if there is no effective security audit and compliance management.

Case Study 9.2 Risks Associated with Proprietary Information Systems

Dean (2012) reported in Ponemon Institute Research that 28 per cent of the internal information theft cases in 583 US companies occurred among the mobile workforce, of which 44 per cent of the companies surveyed still view their IT infrastructure as relatively insecure, while 90 per cent have had cases of information theft at least once in the prior 12 months. This report shows that some business organisations, including retail companies, allow their employees to store valuable customer personal identifiable information on online applications such as Google Docs and Dropbox.

Verizon DBIR (2012) agrees with Dean (2012) and indicates that out of 447 business organisations that participated in their survey of how employers use social media in their business, 52 per cent of small businesses depend on social networking sites, with only 8 per cent of small businesses monitoring what staff post on those sites. These business practices expose the data to theft and make customer PID/I vulnerable to information theft. In some cases, the use of social networking sites—LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook—leaves digital trails that make online companies susceptible to social engineering.

9.4 The Strategy for Information Theft Prevention

This strategy was developed to support federal, state and local law enforcement agencies for the prevention of internal information theft and has been recommended for adoption in US businesses. The seven main components of US national strategy are information protection, legislation, partnerships and collaboration, public awareness, reporting procedures, training, and victim assistance. It is vital to emphasise the three key components—legislation, partnership and collaboration and training—because they extend the understanding of the prevention strategies that have been discussed in section 9.2.1 and because of the suggested impacts these practices can have on internal information theft prevention. Table 9.1 summarises these three components.

|

Strategy |

Features and impact on information theft prevention |

|

Partnership and Collaboration |

Strategy for effective information theft prevention has been adopted in many business organisations in the following instances: Indiana State Police for the US Strategic Alliances, Computer and IT and National White Collar Crime Centre (NW3C), ‘Tiered Approach’ among students and IS/T security experts, Scientific Working Group on Digital Evidence (SWDGE), the Nigeria’s Police Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (“EFCC”), the UK’s Central Sponsor of Information Assurance and Office of Cyber Security Office and Cyber Security and Information Assurance (OSCIA), the UK’s anti-fraud scheme—TRADE (Transactis Risk Assessment Data Exchange) which shares transactional data to enable the detection of potential information theft and computer related criminals and fraudsters in business organisations, the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). These collaborative bodies work with an aim to establish standard practices to guide professionals in investigating identity theft crimes and other computer related crimes. They work together, sharing their expertise, both in areas of provision of digital investigatory strategies and evidence, to foster the security threats of businesses. Rosenberg (2010) suggests that a partnership approach, which is used in biological and nuclear arm controls treaties, could help prevent identity theft crimes and encourage robust practices in investigating these crimes across nations, business organisations, industries and sectors. |

|

Legislation |

The harmonisation of data privacy and security legislation across businesses can reduce the bottlenecks during information theft case reporting. Bringing together various cross-border data protection policies provides the opportunity for thorough investigation of information theft in the emerging business networking and outsourcing. This harmonised policy approach to preventing internal information theft at an international level is an indispensable practice that has been pioneered by US governments. Comprehensive legislation on information theft prevention can help to tackle the challenges related to ‘the admissibility’ of electronic evidence and other related legal hurdles. Breyer (2012) suggests in the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence that law seeks decisions that fall within the boundaries of scientifically sound knowledge, but it is sometimes difficult to achieve in practice if there is no existing policy on crimes prevention to support provision for the scientific evidence. |

|

Training |

Continuous training for retail staffers can help immensely to match the evolution of the Information Systems application in retail operations. An anonymous New Jersey Regional Computer Forensics Laboratory (NJRCFL) director and FBI supervisory special agent noted the importance of staff training. He said that being an IT/S security expert in preventing information theft is ‘not only what I know, but what I know that is not so’. It is now the responsibility of computer security experts to update their skills and knowledge of information theft prevention. The G8 on standards for the Exchange of Digital Evidence also emphasised the need for training security experts in preventing information theft. Their argument is based on the conventional security certification: because there are certifications for fraud investigators in other fields (accounting, finance, and banking), the need for certified professional examinations for information theft in computer crimes should be given due consideration. |

9.5 Practice of Information Systems Governance and Security Intelligence

Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC) recommends that practices including IS/T monitoring and CCTV and network intrusion detection systems, system characterisation, and information theft incidents results documentations can improve detection of the likelihood that a privileged user or a dishonest employee may exploit a known vulnerability.

In addition, GIAC claims that application of the control analyses reduces the risks of insider threats to system vulnerability and that control tools such as DirectoryAlert and ServerAlert by NetVision can reduce potential information theft risks.

Forrester and Seeburger (2013) agree with Conte (2003) and suggest three key elements—Define Your Data, Dissect Your Data, and Defend Your Data—for effective internal data security intelligence against internal information theft. Dissection of the data is the process of critical data analytics for security intelligence. It can be defined with an acronym: INTEL—Information, Notification, Threats, Evaluation and Leadership. With efficient data definition and data dissection in place, these principles would enhance the security of information processing in retail businesses.

In addition, efficient implementation of these practical elements could reduce data leakages by encouraging the principle of least privilege—strictly enforce access control, inspect data usage patterns to identify abuse, dispose of data when no longer needed and encrypt data to limit the access. Forrester and Seeburger (2013) further suggest that data with defined location and index would facilitate the development of a life cycle for data classification, cataloguing and data discovery to reduce information theft risks.

9.6 The Use of the Information Security Audit (ISA)

It is important that retail businesses utilise the above prevention strategies—proprietary security, with IS security audit playing the critical role in implementing those strategies. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) suggested that an effective information security audit is more likely to unveil security loopholes and prevent internal information theft risks.

Since an information security audit plays a substantial role in the security of information processing in retail operations, as discussed in Chapter 7, security managers must make a substantial investment in ISA to protect consumers’ PII/D from the emerging social and technological oriented information theft risks. It could be argued that half the combined cost of internal information theft could be the cost of their prevention through effective ISA. Hence, businesses should prioritise practical and strategic IS security checks to avert data leakages which originate from inside business organisations. Case Study 9.3 summarises the investment efforts of UK and US business organisations, as shown by Pricewatercoopers and ACFE surveys.

Case Study 9.3 Impact of Security Audit on Information Theft Prevention

The PWC’s information security breaches (ISB) (2014) reports that 50 per cent of UK companies plan to spend more on IT security and that there was an increase of 9 per cent in 2012 over the previous year. This report also indicated that the UK Cyber Security Operations Centre spends more than £5 million annually on information security issues, while the US federal agencies budgeted about $6.5 billion on data security assurance alone for the fiscal year 2012.

PWC’s Report (2014) on the strategies for identifying information theft risks in business organisations noted that ISA was rated at 75 per cent while other strategies such as IS breakdown and loss of company assets account for 25 per cent. In addition, ACFE (2014) suggested that more than 43 per cent of information theft cases were detected by use of the ISA, of which 7 per cent were detected by independent external security auditing. This report shows that more than 50 per cent of such crimes could be detected by an effective Information Systems security audit.

9.7 Internal Information Detection Mechanisms as Prevention Practice

Use of internal information theft detection mechanisms available to retail businesses would guide the understanding of some elements required for designing effective preventive strategies. It would enable the businesses to make decisions on resource allocation and the implementation know-how on when and how to apply them. Top research organisations (e.g., ISACA, British Retail Consortium (BRC) and Verizon’s Data Breach Investigation Report (DBIR) claimed that detecting internal information theft at the earliest stages of escalation results in fewer repercussions, although not fewer than if these incidents were prevented. This claim suggests that use of the IS/T security controls may not offer absolute detection mechanism as they have their downsides—cost, complexity and implementation. However, attention should be directed towards understanding the timeline of internal information theft incidents in relation to detection. Understanding the time frame for incidents could increase the ability to provide comprehensive prevention capability evaluation. The time span or timeline for internal information theft incidents depends on a variety of factors and incident detection processes.

The Verizon’s DBIR (2014) categorised the timeline analysis of information theft incidents into three phases: pre-incident, active incident and post-incident. The pre-incident phase is the initial phase of the incident which depicts time from the first action taken against the victimised company by the perpetrator until the time when IS/T property is affected. This is common with network resources intrusions and point of sale (POS) abetted hacks. According to Verizon’s (2013) DBIR Report, 85 per cent of internal information theft incidents under this phase occurred within minutes or less. The time for the pre-incident phase depends on the complexity of security platform of the victim companies. BRC indicates that large retail companies have a shorter pre-incident time than smaller companies because of the complexities associated with managing large IS/T infrastructure and detecting crimes in large retail companies.

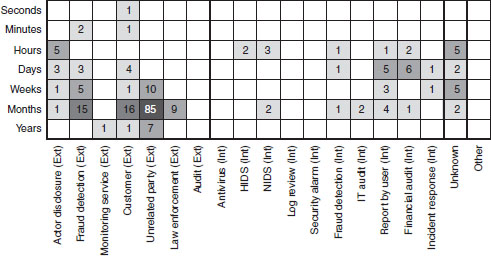

The active-incident phase covers the timespan from the pre-incident phase to the time when PID/I is first removed from the victims’ IS/T control environment. In average, the time for this incident phase is longer—the time it takes the perpetrator to explore the network, locate and exploit the relevant IS/T platforms and then exfiltrate/collect the critical information. Figure 9.1 (adapted from Verizon’s DBIR, 2013) summarises the approximate days taken for internal information theft incident to be detected by various mechanisms: actor disclosure, fraud detection, monitoring service, law enforcement, audit, anti-virus, etc.

Case Study 9.4 Information Theft Detection Mechanisms and Time Span

The Computer Security Incident Handling Guide (Chichonski et al., 2012, see Figure 9.1) shows that it takes 15 months for the fraud detection team and nine months for the law enforcement, compared to less than six months recorded for the same incidents to be detected by the internal party. There could be various reasons attributed to these delays in detecting internal information theft cases. In some cases, the nature of the business operation may lead to delays; the victim companies might have contingency plans in place to manage the business disruption while the investigation can be carried out. Another reason attributed to the delays associated with detecting the internal information theft incidents is that more than 78 per cent of the incidents are committed during working hours. In some cases when the incident were not committed during the working hours, more than 50 percent of internal information theft cases were detected months after the departure of the perpetrators from the victimised companies.

The Computer Security Incident Handling Guide (CSIHG) posits that abetted SQL injection related incidents fall into the active-incident phase and are common in both small and bigger retail companies. The post-incident phase describes the time from the active-incident phase to the time the victim discovers the incident. Some internal information theft cases which are categorised as post-incident could remain undiscovered for months. The post-incident phase may cover as much as months. Some cases can take years because the perpetrators cover their trails, especially in the case of incidents that are perpetrated by software engineer/administrators. This phase could extend to as much time as it takes the victim to detect or to discover the security breach, which sometimes proves impossible. Most post-incident cases are discovered by external parties (e.g., notification by an informant/customer, law enforcement, competing organisations, Internet Service Providers).

Case Study 9.5 Detection of Internal Information Theft in Small and Large Businesses

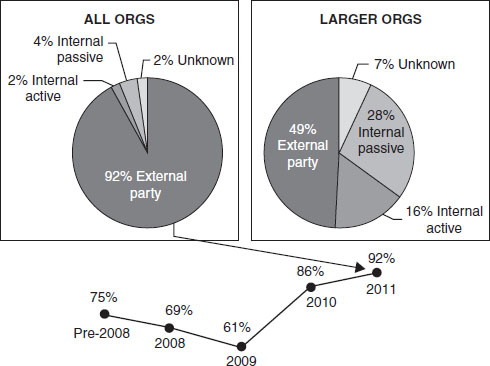

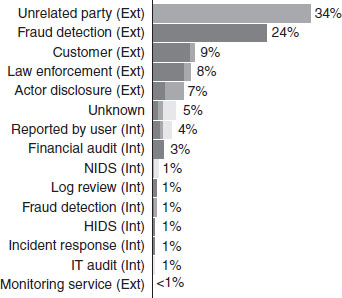

Verizon’s DBIR (2012, 2013) suggests that more than 50 per cent of internal information theft cases in large business organisation were detected by an external party, whereas, in aggregate, irrespective of the size, 92 per cent of these known incidents were detected by the same external party (see Figure 9.2). The larger companies recorded only 16 per cent of the active detection by an internal party and only 2 per cent of internal detection was recorded in all the organisations studied. But, in all, external parties are the largest source of internal information incident detection. In particular, Verizon DBIR (2013), as shown in Figure 9.3, suggests that few technical methods could be used to detect information theft incidents. The reports agrees that end-user activities are the most effective means of detecting information theft incidents. End-users can detect information theft through suspicious e-mails and slow system performance in the course of their daily job operations. Other common internal methods include fraud financial audit, log review, IT audit, and incident response (see Figure 9.3).

9.8 Summary of Chapter 9

As a summary to this chapter, Table 9.3 lists common methods of perpetrating internal information theft in retail businesses and the corresponding recommended prevention and detection strategies. However, it is important to emphasise that retail companies should implement the recommendations which might be practicable in relation to their size and business processes. Even with the most recommended prevention practices that have been recognised and implemented by a consortium of security professionals, there is no one-size-fits-all internal information prevention or detection strategy/practice. Hence, the application and implementation of practices and strategies across business operations will differ depending on budget, business need, and process and size.

|

Mechanisms |

Detection |

Prevention |

||

|

Infiltrated hacking: access to protect IS with stolen credential. |

Monitoring of administrative/privilege activity: logon time, anomalies, malware on the system |

Controlled authentication: two faction, Internet protocol blacklisting, internal restricted administrative connection. |

||

|

Abetted botnet and infiltration. |

Registry monitoring and examination of the active system processes. |

Integrity control mechanisms, Egress filtering via ports and protocols, host intrusion detection systems (IDS), updating firewalls and software security. |

||

|

Tampering and copying of PID/I |

Some scratches on the IS device, Bluetooth signals. |

Employees training, Consistent inspection, policy implementation, anti-tampering tools—tamper switch, epoxy electronics. |

||

|

Social engineering and manipulation |

Call logs, e-mail logs, unusual communication, bypass of technological alerting mechanisms, visitors’ log. |

Clearly defined policies and procedures, general security awareness training. |

||

|

Collusion and employees abetted cybercrimes |

Routine monitoring of the databases, webserver, IDS and intrusion prevention systems (IPS) |

Principles of least privilege account management, input validation and whitelisting techniques |

||

|

Collaboration with external agents |

Last logon banner, end-user behavioural analysis, logon source location analysis |

Disabling default account, scanning of passwords, password-change rotation principle, sharing of the administrative duties. |

||

|

SQL via back-end databases |

Desk calls for account lockouts, sequential guessing and log in attempts failures. |

Password policy, password throttling and effective access control mechanisms. |

References

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2014). ‘Report to the nations on occupational fraud and abuse: global fraud study’. Available: http://www.acfe.com/rttn/docs/2014-report-to-nations.pdf, Accessed 20 April 2014.

Breyer, S. (2012). Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence (3rd edn). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, pp. 1–968.

Cichonski, P., Millar, T., Grance, T. and Scarfone, K. (2012). ‘Computer security incident handling guide’, SP 800–61, Revision. NIST. Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800–61rev2/SP800–61rev2.pdf, Accessed 27 October 2012.

Conte, J.M. (2003). ‘Cyber security: Looking inward internal threat evaluation’. Global Information Assurance Certification (GIAC) Security Essentials Certification (GSEC) paper, practical assignment version 1.4b, pp. 1–13.

Dean et al., (2011). Cost of Data Breach Study: Global, Ponemon Institute Research Report, Available: http://www.ponemon.org/local/upload/file/2011_US_CODB_FINAL_5.pdf, Accessed 23/03/2014.

Dean, S., Pett, J., Holcomb, C., Roath, D. and Sharma, N. (2012). ‘Fortifying your defences: The role of internal audit in assuring data security and privacy’. PCW Publications. Available: http://www.PWC.com/us/en/risk-assurance-services/publications/internal-audit-assuring-data-security-privacy.jhtml, Accessed 9 October 2012.

Forrester and Seeburger. (2013). ‘The future of data security and privacy: Controlling big data’. In: The WebCast, The Silent Enemy: Preventing Data Breaches from Insiders, 13 March 2013 at 13:00–14:00 EDT.

Hinds, J. (2007). Tackling Staff Fraud and Dishonesty: Managing and Mitigating the Risks. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development Guide.

Hutchins, E.M., Cloppert, M.J. and Amin, R.M. (2010). ‘Intelligence-driven computer network defence informed by analysis of adversary campaigns and intrusion kill chains’. Available: http://www.ciosummits.com/LM-White-Paper-Intel-Driven-Defense.pdf, Accessed 29 July 2013.

PriceWaterCoopers (PWC). (2014). ‘Information Security Breach Survey (ISBS) technical report’. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/307296/bis-14–767-information-security-breaches-survey-2014-technical-report-revision1.pdf, Accessed 2 April 2014.

Rosenberg, B. (2010). ‘Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) build Cyber Range to test security measures’. GCN: Technology, Tools and Tactics for Public Sector IT Special Report, Available at: http://gcn.com/articles/2010/06/07/defense-it-1-cyber-range.aspx]; Accessed on 31 January 2013.

SANS Critical Security Controls. (2008). ‘Critical security controls for effective cyber defence’. Available: http://www.sans.org/critical-security-controls/, Accessed 20 April 2013.

TechNet Blogs. (2013). ‘Introducing Enhanced Mitigation Experience Toolkit (EMET) 4.1’. Available: http://blogs.technet.com/b/srd/archive/2013/11/12/introducing-enhanced-mitigation-experience-toolkit-emet-4–1.aspx, Accessed 22 December 2013.

UK Fraud Advisory Panel. (2011). ‘Fraud Facts, Information for Individuals’ (2nd edn). 1, pp. 1–2. Available at: https://www.fraudadvisorypanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Fraud-Facts-1I-Identity-Fraud-Revised-Sep11.pdf, Issue 1 September 2011 (2nd edition).

Verizon. (2013). ‘Data breach investigation report’. Available: http://www.verizonenterprise.com/resources/reports/dbir-series-why-businesses-are-attacked_en_xg.pdf, Accessed 27 December 2013.

Verizon, (2014). ‘Data Breach Investigation Report’. Available: rp_Verizon-DBIR-2014_en_xg%20.pdf, Accessed 3 May 2014.

Verizon RISK Team Survey Report. (2012). ‘Data breach investigations report’. Available: http://www.verizonbusiness.com/resources/reports/rp_data-breach-investigations-report2012_en_xg.pdf, Accessed 23 April 2013.