CHAPTER 2

VISUAL CONTENT AND HUMAN NATURE

“The broader one's understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have."

—Steve Jobs

While advancements in technology helped fuel the rising demand for visual content, our universal embrace of that content must be considered an equally valid indicator of its power and effectiveness. When organizations were competing for their corner of the internet, the ones that led with visual content saw far more success than those that relied on text-heavy alternatives. In fact, the most successful innovations that followed were often founded on a visual-first mentality.

So what has driven audiences to crave visual content above all else? To answer this question, we have to understand human psychology and our innate predilection toward visual communication.

Scientists, philosophers, and linguists have debated the origin of both verbal and written language for centuries. Did the ability to communicate through a common language occur as a learned social construct, or was it a sudden evolutionary shift wherein our species developed a natural inclination to formulate words from thoughts? This particular debate may never find a true answer, but there is no debate that verbal and especially written language developed long after the earliest humans appeared.

When challenged with the need to communicate, early hunter-gatherers expressed themselves with visual depictions of their message long before the tools for written language became the norm. In other words, visual language first arose as a response to our need to communicate and build connections.

Cave paintings are the first clue to suggest that the human species is hardwired to speak visually. In the same way our own fight-or-flight instincts can be traced back to our ancient ancestors, our bias toward visual expression has remained part of our natural makeup as well.

One of the most exciting ways to witness our inherent need to connect and communicate visually can be seen in the reactions of toddlers turning the pages of picture books. Long before a true understanding of the words on the page can be formed, colors and illustrations demand their attention. We are attracted to visual content even before a written storyline endows illustration with meaning.

THE BRAIN SCIENCE OF VISUAL COMMUNICATION

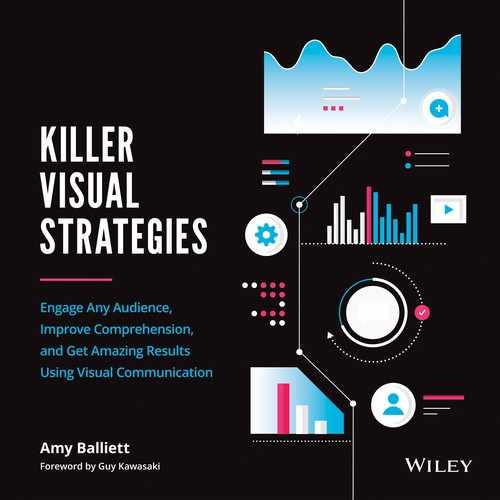

Brain science suggests that our natural inclination to communicate visually is a dominant human trait. In fact, 30 percent of our cerebral cortex is composed of neurons firing together to drive visual processing, according to Discover. When compared with only 8 percent for touch and 3 percent for hearing (see Figure 2.1), this suggests that we prefer visual communication innately.

Source: Grady, “The Vision Thing.”

One of the most notable pieces of evidence for just how integral visual communication is to the human brain comes from a 2005 study called Project Prakash. Led by MIT professor Pawan Sinha, Project Prakash worked with the Shroff Charity Eye Hospital in New Delhi, India, to help restore sight to those who were blind as a result of congenital disease.

According to MIT, 30 percent of the world's entire blind population resides in India. The numbers are so vast because many of those suffering from blindness either lack access to quality health care or lack the financial means to obtain it. According to estimates from the World Health Organization, 60 percent of India's blind children die before they reach adulthood, despite the fact that more than 40 percent of cases are preventable or treatable.

In a seemingly hopeless situation, Professor Sinha saw opportunity. With the help of undergraduate and graduate students at MIT, as well as postdoctoral fellows, Sinha established a presence in India to help cure blindness in more than two thousand patients! Beyond the great humanitarian effort, his work took the scientific understanding of how our brains learn to see to an entirely new level.

Figure 2.2

Source: Project Prakash.

From 1981 until Sinha's findings in 2005, the general opinion of the scientific community assumed that the brain could not perform visual processing if sight were restored after six years of age. This theory came from a series of studies performed by scientists David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel in the late 1970s and early '80s. They would later win a Nobel Prize for their work in visual physiology.

Their work surmised that the visual cortex, left unused for a period of time, would do what other parts of the human brain does: rework itself to give more attention to our other senses. This theory is exemplified most iconically in the case of Stan Lee's famed comic hero, Daredevil. This blind protagonist wasn't hindered by his impairment. Instead, his blindness improved all of his other senses, allowing him to best his presumptuous adversaries with ease.

Of course, life is not a comic book, and the brain's visual processing capabilities seemed to Sinha to be far too powerful to simply be overtaken by senses that the brain already gives less priority to. So, Sinha sought to challenge the work of Hubel and Wiesel. He went to India, where he could cure children and adults of long-term blindness while gaining insights into how their brains would rebound, if at all.

What he uncovered challenged more than twenty years of scientific understanding. Not only did every patient regain sight, but even adults who had been blind for decades saw full recovery. In other words, the visual-processing part of our brain is so powerful that, even after years of no sight, the gray matter will wake up and, where needed, repair itself.

In the weeks following restoration of sight, Sinha was able to run a plethora of tests on patients to determine how the brain learns to see. During this time, he learned that our brains process simple shapes before complex imagery. This suggests that elements like simple iconography can connect with the human brain faster than detailed illustrations and photography. He also learned that moving imagery is far easier for the brain to process. This might explain our penchant for television, cinema, video, and motion graphics.

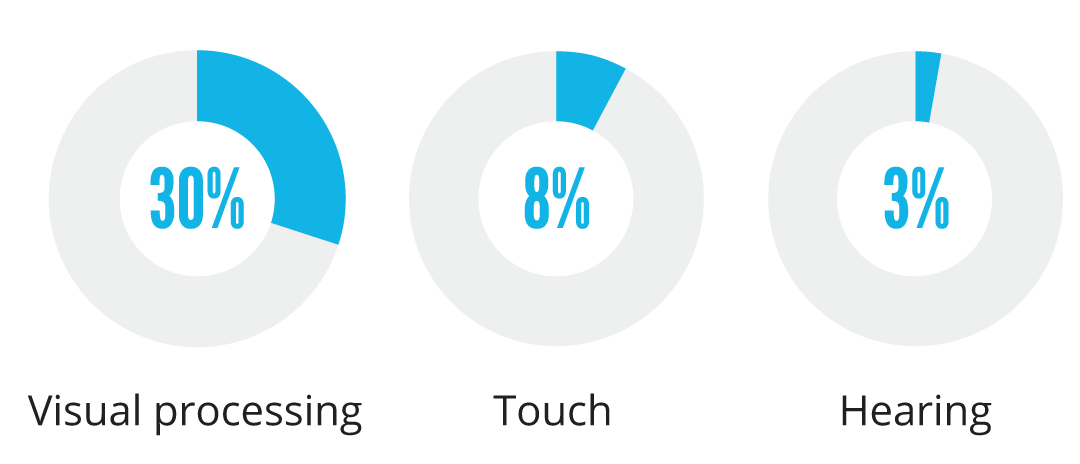

Visual communication is clearly a guiding priority for the human brain. In fact, multiple studies have tried to quantify the brain's visual-processing abilities. The most notable, which was published in the SAGE Handbook of Political Communication by Semetko and Scammell in 2012 and has held up ever since, stated that visual information gets to the brain sixty thousand times faster than any other form of communication that exists (Figure 2.3)!

Source: Semetko and Scammell, The SAGE Handbook of Political Communication.

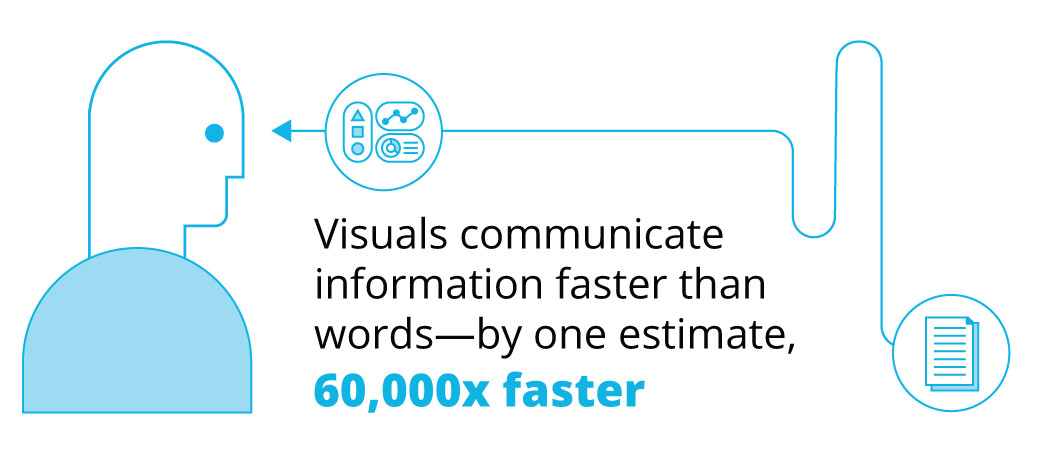

Sources: Jensen, Brain-Based Learning: The New Paradigm of Teaching; Brysbaert, “How Many Words Do We Read per Minute?”

Source: McQuivey, “How Video Will Take over the World.”

To put this into perspective, the human eye can register 36,000 visual messages in any given hour, reports Dr. Eric Jensen, author of Brain-Based Learning (Figure 2.4). In comparison, the average adult can only consume 14,280 words of text in that same hour, according to meta-analysis published by Marc Brysbaert of Ghent University in 2019. With visual content, the brain quickly discerns meaning by creating messages, but with text-based content, the brain must string together words to form sentences that then create meaning. To up the ante even more and give a nod to Sinha's findings, Forrester Research suggests that just one minute of video is worth 1.8 million words (Figure 2.5)!

We are predominantly visual learners as well. As e-learning has become more popular, educators have had to find ways to improve understanding outside of the classroom. They found that combining text with graphics led to an 89 percent increase in comprehension when compared to just delivering text alone, as reported in e-Learning and the Science of Instruction, a handbook for e-learning professionals.

Our brains come prepackaged with the toolset to take any information that we consume and convert it into a visual format. To test this, take a moment to ask those around you what they think of when you say a simple word like “dog.” You'll notice that, for some, an image of dogs will pop into their heads, while others will think of cats, a bone, and so on. Very few people, if any, will tell you that they thought of the letters d-o-g. In fact, if someone does think of the letters, ask them if they are multilingual. It's often those who have trained their brains to speak across languages that have to process information in this way. This is because we don't instinctively think in text—we instead think visually.

SPEAKING VISUALLY IS NATURAL—AND NOW, IT'S EXPECTED

The technological advancements of our modern age have placed us all in a constant state of information overload, and we are eager to seek cover from the storm. We crave information, but in order to process it all we yearn for clarity in the noise. Because of this, we have instinctively turned our attention to the easiest-to-digest content media out there: visual media. It's because of this that the brands that deliver successful visual strategies are those that value the innate expectations of their consumers. Those that still lead with text will continue to struggle.

But we are discerning creatures. Just as we can process visual content in an instant, we can judge that content equally as fast. While organizations continue to lead with new media such as infographics, e-books, motion graphics, and more, they have to consider the execution of this content. Just like my first two attempted infographics, simply placing images next to paragraphs of text won't work, because it forces the viewer to read the content to understand the visuals. Instead, to succeed in a world that demands a visual conversation, organizations must lead with true visual communication.

Visual communication graphically represents information to efficiently and effectively create meaning. When needed, limited text is used to explicate that meaning. In other words, your visual choices must speak louder than your text. Your audience is ready to process your visual information, but not if that content makes little sense without the support of text to elevate it.

But how do you deliver content that both takes advantage of our modern platforms and connects with our fundamental instincts? In the second part of this book, I'll explain exactly that.