CHAPTER 12

RULES ARE MEANT TO BE BROKEN

“Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

—Pablo Picasso

The rules of visual communication should lay a strong foundation for delivering high-quality visual content for your audiences. By understanding and applying each rule, you'll find it easier to consider the subconscious effects that different design choices will have on those viewing the content.

But it is rare that every rule can be perfectly executed in every piece of content you produce, because different factors may force you to prioritize some rules over others, or even break a rule entirely. This is OK, provided that bending or breaking a rule will help you better represent the information or achieve your goals with more efficiency.

Some rules are easier to bend or break than others. For example, rule 2 (small visual cues have a large impact) and rule 7 (use proper data viz throughout) are two that I would suggest you always follow. Even in satire, breaking these rules can do more harm than good. Additionally, a rule should never be ignored simply because it's too hard to follow. Instead, each rule should be weighed in the context of the goals of the project, the information being delivered, the ways in which an audience will view the content, and the target audience. To exemplify this, here are projects from my team at Killer Visual Strategies in which we bent or broke some of the rules outlined in this book.

BREAKING RULE 1: ALWAYS THINK ABOUT CON-TEXT

The rule of con-text is usually the first to be broken when producing visual content. This makes sense, because it's far easier to let text drive meaning in visual content than it is to let the visuals themselves carry forward information. That said, this rule should never be ignored simply because it's easier to rely on text. Instead, only break this rule when it is completely impossible to visualize the information without including a little more text.

You can't simply display icons without labels for those icons; you shouldn't show a bar chart without labels and a title; and great visual content is easier to digest with headlines breaking up sections within the design. These are all times when text is needed, but even in these instances, you aren't really breaking the rule as long as your visuals represent the information clearly.

Consider a flow chart, though. Most flow charts require a series of yes-or-no questions and labels. But this doesn't mean that they're not great examples of visual communication. Before reading the questions or labels, a viewer can easily discern that they are about to experience a decision tree. The sizes and shapes of labels and boxes may even imply a pattern within the tree. Color choices might also drive the eye to conclusions. And the arrows within a flow chart set a pace and direction for the viewer. As a result, there are multiple visual cues to make the information easier to consume, even if incorporating text is necessary to help audiences along the way.

Perhaps the best example of this rule being broken lies in my favorite project ever produced by my team. When asked to create a poster showcasing the large footprint of the tech sector in Washington State (with a primary focus on the Puget Sound and Seattle areas), our team was tasked with visualizing a list of nearly 1,000 company names and their relationships to one another.

The goal of the piece was to show which companies fueled innovation and how companies were connected to one another. For example, maybe a former Microsoft employee went out on their own to start a new and successful company. Or perhaps a leader from Expedia teamed up with a leader from Amazon to build a new brand. By studying the history of founders alongside the largest names in the Pacific Northwest, we could begin to connect the dots of innovation, so to speak.

View the resulting design in Figure 12.1.

While this design is exceptionally text-heavy, it still lets visual communication guide the viewer. Text is used only for labels, because delivering the same visual with logos would create a cluttered and harder-to-navigate design. Arrows and circle treatments are used to lend meaning to the text and communicate the information visually.

- Circles are used to indicate three types of companies:

-

- Solid circles with dots in the center show companies that have been acquired.

- Solid circles on their own show companies that have not been acquired.

- Solid circles that rest inside a hashed external circle represent engineering centers. Engineering centers are companies that were founded outside of the Pacific Northwest, but have a large presence and workforce in the area.

- Arrows lend further meaning to the design by depicting the relationships between companies:

-

- Solid arrows guide a viewer from a company where founders were previously employed to the companies they founded, thus linking innovation to key hubs like Microsoft, Amazon, the University of Washington, and others.

- Companies with multiple founders are indicated through dotted-line arrows connecting out from the businesses the founders left to start their new businesses.

- If a company was acquired, a dashed line connects them to the organization that acquired them.

- The direction in which the arrow points also drives meaning. The arrow always points away from a company where someone was employed and toward the company they started.

- In the case of acquisitions, the arrow points from the acquirer to the acquiree.

Upon initially viewing this design, one can quickly identify the largest innovation hubs in the Puget Sound region. The visualization proves their impact and value both inside and outside Seattle. Once an audience is hooked, they can spend hours mapping the connections between each company. While this poster has at least 1,000 words of text, it doesn't hurt the design in this situation. The rule of con-text has been broken, but the piece still leads with visual communication at its core.

BREAKING RULE 3: THERE'S NO GOLD AT THE END OF THAT RAINBOW

Great designers will likely look at this rule and throw it out the window immediately. While it's imperative to use color intentionally, in a way that delivers meaning wherever possible, experienced designers are able to achieve this even with a more robust color palette. If you are not a designer or are just starting out, however, it is still encouraged to follow the three-color rule.

When we started Killer Visual Strategies in 2010, our focus was mainly on infographic design (hence our original name, Killer Infographics). Much of what we were creating included data-rich designs that benefited from sticking to the three-color rule. Often, when delivering a data-rich piece of content, it's important to stick to a pattern of colors. This ensures that viewers won't read meaning into your color choices when looking at the various data visualizations. But what happens when a piece of content isn't driven by data viz? It took a year before we truly came across this dilemma, and decided to break the rule of rainbows.

We were hired to design a series of infographics for an information technology (IT) certification program. The client wanted to stand out from his competitors, who were providing potential students with data-rich arguments about the benefits of a degree in IT. But in our client's opinion, if someone was already looking at a certification program, they probably knew the benefits. Instead, our client wanted to appeal to students on a more personal level. He wanted to show off his brand's personality by making students laugh. He also wanted to gain backlinks to the program website by creating something that would inspire debate and conversation.

These priorities inspired “Geek vs. Nerd,” the first infographic in what would become a series. Figure 12.2 shows an excerpt of the design, the piece that acted as the visual hook.

The design went viral within days of its release. While some agreed with the differentiators between geeks and nerds, a small subset of the population was wholly offended. A pattern emerged in which people claimed that some of the traits called out in the infographic should in fact apply to “hipsters” rather than geeks. This inspired the second infographic in the series, “Geek vs. Hipster” (excerpted in Figure 12.3).

The “versus” series continued with “Seattle Geek vs. Silicon Valley Geek” (excerpted in Figure 12.4) and “Guy Kawasaki vs. Seth Godin” (excerpted in Figure 12.5; see also Figures F.1 and F.2).

As you can see in all of these examples, myriad colors are used to bring the content to life. In each case, illustrated scenes of people are shown and colors help to bring important details to life. In the case of “Seth Godin vs. Guy Kawasaki,” the dominant purple choice for Godin and the dominant red for Kawasaki was very intentional. At the time, Godin was best known for his book, Purple Cow (which sported a purple cover with cow spots), while Kawasaki was best known for his book, Enchantment (which had a red cover with a butterfly).

As you can see, in all of these examples, the rule of rainbows was ignored. Despite this, colors were used with great intent. In each case, the designer chose a dominant color to connect with each topic, and carried that color forward throughout the design.

Figure 12.2 []

Figure 12.3 []

Figure 12.4 []

Figure 12.5 []

BREAKING RULE 4: GOOD VISUAL STRATEGISTS ASK “WTF?!”

While fonts carry forward meaning, oftentimes a brand requires that its fonts be used in all of its content. This can be difficult for any designer, because their creativity becomes restricted.

To put this into perspective, imagine facing a home-remodeling project where the only tools at your disposal are a screwdriver, a hammer, and a handsaw. Sure, you can likely get the job done with those tools, but a power saw and drill would be two simple additions that could greatly improve your efficiency. Fonts are tools to communicate a mindset or emotion, but what if you couldn't leverage those tools accordingly?

When working with large brands, designers might find that sticking to their fonts is often more important than deviating from them to deliver a larger impact. This has been true for the Global 2000 companies we have worked with for years. To maintain quality standards within very large organizations, restricting communicators to a specific set of fonts is a must.

When a brand forces their fonts on a design, it should never be a deal-breaker. Instead, it should be embraced as a challenge while font weights and sizes should act as the solution to that challenge. In other words, while your toolbox is light, how you wield those tools makes a big difference.

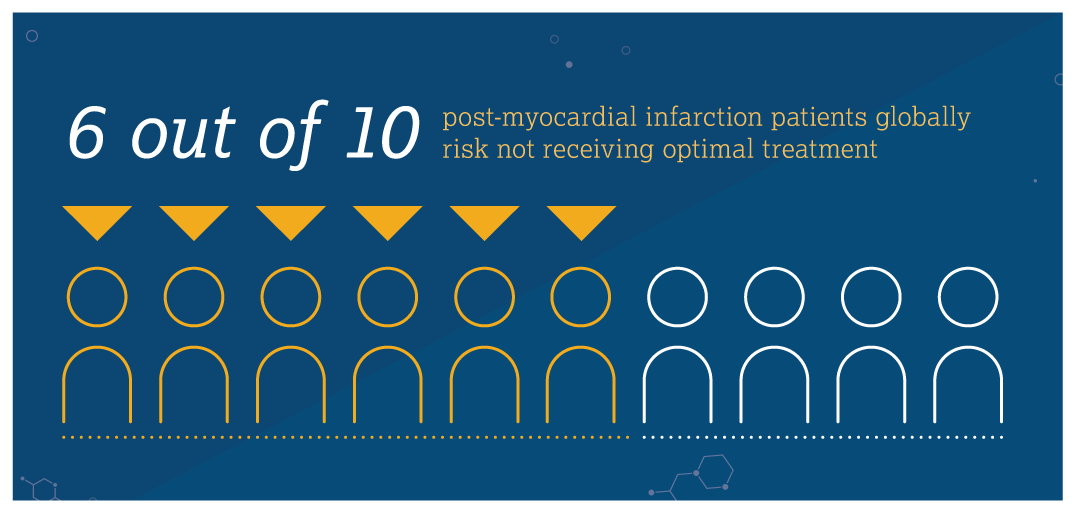

To exemplify this, consider a series of assets we designed for a client with Lexia as their primary brand font. Take a look at the screenshots from key scenes, shown in Figures 12.6–12.8. You'll see that this font is elevated by the designer through size differences, color choices, and bolder weights where appropriate.

Figure 12.7

As you can see based on subtle visual cues in the design, this client lives in the world of science and medicine. Their brand font choice communicates an authority and professionalism that works well for their industry. So it makes sense that all vendors must adhere to these brand choices, despite the fact that it breaks the WTF rule. When forced to break this rule yourself, consider how font sizes, colors, and weights can be used to elevate font choices and draw the eye into key points.

BREAKING RULE 5: AVOID THE STIGMA OF STOCK

Chapter 8 offers multiple tips on how to use stock imagery if you are unable to use anything else. But other times, you may find that you don't need to break the rule, but that doing so will add efficiencies without hindering the overall success of your end deliverable.

To exemplify this, consider the illustration in Figure 12.9, excerpted from a design we created at Killer called “Are You Working Your Employees to Death?”

While the illustration is very compelling and acts as a great visual hook for the audience, it was also quite time-intensive to produce. Would this piece have lost its value if the stock image in Figure 12.10 were used instead?

Figure 12.9 []

Figure 12.10 []

By adding filters and properly framing this photo within the design, you could still ensure the infographic packs a powerful punch. It may not be as engaging as a custom illustration, but it can work in a pinch if you have time or budget constraints.

In the context of editorial design, stock imagery can have even more of a place than custom illustration. Editorial design typically comes in the form of PowerPoint presentations, white papers, e-books, blog posts, and multipage reports. Great editorial design contains a healthy mix of slides or sections driven by visual communication and other segments primarily dedicated to long-form text.

When developing content like this, it often helps to break up the long-form text with photography because iconography, data visualizations, or illustration may not feel appropriate to the content. I'd still encourage you to use custom photography over stock imagery, but I know that it's rare for small and mid-sized organizations to have their own collection of custom photos.

Check out Figures 12.11–12.13 to see a few examples of how stock photography can be used within editorial design to keep the viewer engaged.

As you can see, there are times when this rule can be bent or broken, but applying unique filters and framing to your stock photos can go a long way toward making them feel custom and original.

BREAKING RULE 6: STAND OUT AT THE COCKTAIL PARTY

“My target audience is everyone!” This is what one of my clients exclaimed when I shared the rule of standing out at a cocktail party. Sometimes company goals or budgets greatly restrict the ability to create content geared toward specific target audiences. In other words, it's not always easy to stand out at a cocktail party. There are cases in which you might make a group announcement in the hopes that enough people have stopped their conversations long enough to listen.

When delivering content geared toward the Everyman, it's important to make safe choices. This happened for our team at Killer in 2014 when a team at the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) hired us to revamp their visual identity and build a five-year content campaign. At the time, they were entering their fiftieth year of service to the arts community and needed a partner to help them make inroads with new donors and constituents, and to ensure another fifty years of success.

As an agency, we were tasked with building a visual language that would speak equally to a donor base older than forty-five, legislators in Washington, and younger generations who had not heard of the NEA or didn't understand its value. See what we created in Figure 12.14.

This visual language seems simple at first, but every single design choice ensured equal treatment of each target audience. Consider the following distinctions:

- The color palette is intentionally broad. It is Americans with Disabilities Act–accessible, which is required by any government organization. What's more, it includes a variety of colors so that they can be applied based on which segment of the NEA's broad audience each asset is speaking to. When a topic would matter more to a legislator than a millennial, for example, more muted tones from the color palette can be used to let the information be the star of the design.

- The font choice is modern, thin, and sans serif. This speaks equally to all audiences, but the thin font choice ensures that it can be taken seriously by a more mature viewer.

- The data visualization style is intentionally simplified. When communicating important information to government officials, it's important to lead with authority. By sticking to traditional charts and graphs, we ensure that nothing feels convoluted or misrepresented. Meanwhile, the use of donut pie charts instead of traditional pie charts lends the content a modern look that attracts younger viewers.

- Character illustrations are purposely faceless. By choosing this detailed silhouette style, character illustrations can be easily altered to represent various demographics, across both age and race. In addition, the lack of facial expression ensures no viewer is alienated when viewing characters that may be intended to represent them.

When you're forced to break the rule of standing out at the cocktail party, you can still make smart design decisions that ensure flexibility and speak equally to a variety of viewers.

BREAKING RULE 8: COMMIT TO THE TRUTH AND PROVE IT

You may be wondering why some rules were omitted from this chapter when this rule—about something as important as always committing to the truth—was not. The term “fake news” has broad implications—to such an extent that it has become a catch-all phrase often used for political gain. Should a government official want to ignore some fact, they can publicly defame reports of said fact as “fake news.” This has led to a black-and-white view of information and content that deserves to be challenged.

In the October 2019 issue of American Behavioral Scientist, researchers from Penn State University categorized fake news into seven distinct buckets: false news, polarized content, misreporting, commentary, persuasive information, citizen journalism, and satire. To juxtapose these, they noted that trustworthy content follows journalistic standards such as citing reputable primary sources and adhering to a grammatically correct, impartial, and authoritative written style.

It's easy to find examples of powerful visual content across all seven buckets of fake news. But to maintain the trust of your audience, it is highly encouraged that you avoid creating content that could be categorized as false news, polarized content, misreporting, and citizen journalism. That being said, there is a prominent place for satire, persuasive information, and commentary in visual content that should be embraced rather than avoided.

Figure 12.15 []

Explainer videos, which often tell the story of a brand product or service in less than ninety seconds, are a great example of persuasive information. A good explainer video will include data points from external and reputable sources, but may often include claims from the company behind the video as well.

When the Killer team produced a motion graphic for our friends at the Happy Egg Company, a free-range egg brand, the script we wrote included the claim that “happy hens like to look good” along with a variety of other assumptions surrounding the preferences of a “happy hen.” (You can view a screenshot from that video in Figure 12.15, or watch the full motion graphic at bit.ly/HappyEggVideo.)

Of course, who actually knows whether hens feel happiness? Should this motion graphic be considered untrustworthy as a result? The simple answer is no. This video may take creative liberties, but it was made as both a persuasive form of content and entertainment. Because it was packaged as such, the audience expects to willingly suspend disbelief during the 65-second run time.

Visual content also acts as a great vessel for satire and commentary. The infographic “versus” series I referred to earlier in this chapter is a great example of satire mixed with commentary. While, yes, some well-sourced data points complement the caricatures in each design, there isn't a reputable source out there that would claim to know the exact characteristics of a geek, nerd, or hipster.

Pop Chart, whose “Insanely Great History of Apple” poster I talked about in chapter 9, delivers an abundance of satire within the infographic posters its team develops. Some of the best include their “Alphabet of Animal Professions” and their “Periodic Table of Hip-Hop.”

When breaking rule 8, it's important to make it obvious to your audience that you're working within the realm of satire or commentary. Applying a journalistic style implies the content should be taken seriously. This may backfire if the topic is too believable, as it did for Orson Welles when his dramatized reading of The War of the Worlds on live radio in 1938 caused widespread panic.

To ensure your content is viewed as satire or commentary, consider using a more conversational tone within the text of the content. Choose a title that is obviously humorous or incorporate modern slang within the piece. If it still doesn't seem clear, be sure to label your content as commentary or satire to ensure your audience doesn't misinterpret your intent.