If you build a unique bot of some sort, someone with an EV3 kit might ask you for instructions on building a duplicate. There are numerous methods for demonstrating how to build a robot that you have designed. One easy method is to simply digitally record yourself building it, talking as you go and showing to the camera the pieces you are using and where you place them. I’d like to also introduce to you something called CAD (computer aided design) software. This type of software allows you to create accurate drawings of your robot designs as well as step-by-step instructions that can be printed or viewed on a computer screen; examples of CAD programs used for LEGO creations include LDraw ( http://www.ldraw.org ), MLCad ( http://www.lm-software.com/mlcad ), and from LEGO, the LEGO DIGITAL DESIGNER ( http://ldd.lego.com ).

For this book, I’ve been using photographs taken with a digital camera. With the digital camera, I can immediately upload the photo to my computer (a laptop in this case) and view the image. If it’s blurry or doesn’t show quite what I wanted to capture, I can delete it and take another.

This appendix is a short tutorial containing some tips and suggestions I want to pass along. I’ve learned a lot from photographing this book’s bots and I’m hoping some of my experiences can help you if you choose to create building instructions (BI) from photos of your own bots.

What Will the Background Be?

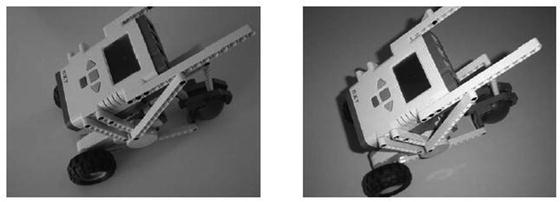

One of the biggest mistakes I made early on was to photograph the construction of my bots against a white background. After converting the photos to black-and-white images, what I found was that the colors of most of the EV3 parts (off-white, light gray, dark gray) just didn’t show up very well when I placed a white posterboard under the parts. Take a look at Figure D-1. On the left is a bot against a white background, and on the right is the same bot against a yellow background. After converting the photograph to a black-and-white image, which do you think looks better?

Figure D-1. The background can make all the difference

I also tried photos using blue, green, red, and gray posterboard. What I found was that yellow or light-blue posterboard worked best. Whether you convert the pictures to black-and-white or not, photographing your bot’s assembly against a colored background instead of white works much better. Even better is to use a colored background with some texture.

Step by Step Picture-Taking Strategy

I’ll jump straight to the secret for taking great BI photographs: Build your bot first. Get it perfect, the way you like, and make sure it works, and then start taking pictures as you take the bot apart.

You’re right, this is not a big secret. You’ll photograph the bot as it’s disassembled and then reverse the photographs. Simple. But I do have a couple of suggestions for you:

Your first photograph should be of the completed bot: When you are done, you’ll reverse the picture order, so this will actually be your last building instruction photo. Whatever angle you use to take a picture, that is the angle you need to keep for the next photo.

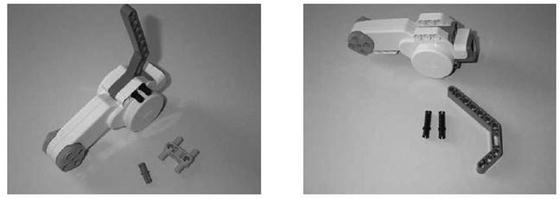

Without moving the bot, remove a part and set it down close to the bot: Take the photograph (from the same angle as the first) so that it shows the bot and the removed part, and make sure that where the part was removed is visible in the new photograph. Look at Figure D-2. On the left side is the final bot, and on the right you can see that a part has been removed. You should be able to determine from the photo on the left where the parts on the right will be placed. Good building instructions always show you a part in one step that you’ll use in the next step (which is why the photo on the left has two new parts next to it).

Figure D-2. Look at the image on the left to determine the placement of the part on the right

Remove multiple parts if they are all visible in the most recent photograph: If you have three 15-hole beams and two small black connectors that can be immediately removed and are not hidden by other pieces, feel free to take all of them off. Place them in an organized fashion near the bot (or what’s left of it) and take a picture. As long as the locations of all the parts you are removing are visible in the previous photo you took, everything should be fine.

As you take more and more photographs, you’ll find even better methods for taking photographs and discover things to avoid. For example, you can’t remove a part on a nonvisible side of the bot that you just photographed. If you take off a nonvisible part, place it next to the bot, and then photograph it, how will others using your instructions know where to place the part? They’ll see the new part to add, but when they look at the next photograph, the part you removed will not be visible.

After you’ve completely disassembled your bot, take the pictures and put them in reverse order. Using a digital camera and uploading the photos to your computer, rename the images Step 1, Step 2, etc. The first image will show the first piece (or first few pieces) of your bot being placed or connected together.

Now, use your new building instructions and try to build your bot. If you took good photographs, you should be able to build your bot again. If anything is confusing, take a picture to capture the proper placement of a part or two where you found the problem. You can give the picture a name such as Step 3b if it fits between Steps 3 and 4.

When you are happy with your building instructions, you can use image editing software to add text to your pictures if you like. Then, upload the images or print them out and share them with others. You can also post your steps to the MINDSTORMS Community (see Appendix A). And now your bot design can be re-created anytime.

After taking the picture, inspect it closely in the LCD screen of the camera and delete any picture that is not in sharp focus or doesn’t clearly show what you want to show. It’s digital, so you can always take another picture, but the model will never be at this particular step again, so check now, and don’t regret it later.

Lighting, Camera, and Lens Choices

Lighting: If at all possible, photograph in strong, indirect light. The built-in flash on most cameras tends to “flatten” the image, removing or reducing depth cues. If you can use a strong, even light source from a different direction than the camera, you have much more control over the lighting and the depth cues in the picture. An inexpensive lighting kit can be as little as $50. Lights, stands, and two white umbrellas make this indirect illumination much easier. Figure D-3 was shot with umbrellas, one to the right and one to the left.

Figure D-3. This image is well lit from the sides, F22, excellent depth of field. But is there some dust?

Depth of Field: For most photos, you’ll need a great depth of field. This means you might shoot at F22 so that items in the foreground are in sharp focus, along with items in the background. A step-up in quality also results from using a non-zoom lens. The photos in this book were taken with a 35mm equivalent lens. This relatively wide-angle lens gives greater depth of field than a 50mm or longer lens.

Exposure: You may want to overexpose your photos for greater detail in dark areas. All of the photos in this book, including Figure D-4, were shot with automatic exposure set to 0.7 stop (that is, 0.7 EV) overexposure. By using an automatic camera, the 0.7 EV boost is consistent across photos. This overexposure, as an example, makes the black details on the wheel hub of Figure D-3 much clearer.

Figure D-4. Enlargement of Figure D-3. What are those little gray dots doing there? Very possibly, they’re dust on the sensor.

Dust on the Sensor: An unwelcome phenomenon can show up when you’re shooting at F20 or F22—dust on the digital sensor. We don’t notice this dust at stops of F2 or F4, but as the aperture closes down the dust becomes more visible. In Figure D-3, we see a normal shot. But in Figure D-4, an enlarged portion of Figure D-3, the dust is more visible. This can be tricky to clean off the sensor but may be essential if you want to avoid a lot of Photoshop after-the-fact cleanup. The camel hair photo brush and canned air “can” be your friends.