3. Your Moral Compass

As we’ve just seen, nearly all of us have an inborn “talent” to be moral. But talent is never enough. Think of the major league baseball teams who spend fortunes on rookies and then send them off to farm teams for a few years to hone their skills. Professional ball players begin with baseball intelligence, but they must train hard to turn their baseball intelligence into on-the-field baseball competence. So they practice technical skills such as batting or pitching, along with nontechnical skills such strategy, judgment, and emotional composure. Why do they work so hard? Because they want to satisfy their goals and desires. Maybe they like winning, or money, or adulation, or they love playing the game. Successful ball players know that getting what they want means doing whatever it takes to reach their goals. In other words, the best ball players make sure that their talents, skills, and actions are aligned with their goals.

Reaching our own personal goals also requires alignment. When we decide to start a daily exercise program but never get on the treadmill, we feel uneasy because our actions are inconsistent with our goals. If we want to go on vacation, we feel good when we book the flight because we’re doing something to reach our goal. Similarly, most of us want to be moral because we crave that experience of consistency between our moral values, our goals, and our actions. We call that state of moral consistency living in alignment.

As important and satisfying as it is to make decisions based on values, aligning your decisions with values doesn’t come easy. There are lots of landmines: emotions, such as fear or excitement, mental biases, such as overconfidence in our leadership smarts, and a brain that was built for hunting woolly mammoths, not riding the roller coasters of life and leadership in today’s complex organizations. In the following chapters, you learn skills to deal with all those obstacles to moral decision making. But first, you need to understand what living in alignment means because that is the foundation for becoming a true leader.

Think of living in alignment as the interconnection of three frames, as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Living in Alignment

The first frame contains your moral compass—basic moral principles, personal values, and beliefs. The second frame holds your goals. Your goals range from the lofty (your life’s purpose) to the ordinary (a new house). The third frame contains your behavior, including thoughts, emotions, and actions. Living in alignment means that your behavior is consistent with your goals and that your goals are consistent with your moral compass. Living in alignment keeps you on course to accomplish your life purpose and achieve the best possible performance in all your life roles.

Mark Phillips, SVP Distribution, Ovations (a United Health Group company), discovered that living in alignment can be difficult, especially when you’re bucking a popular business trend. When Mark was SVP of Sales for Schwab Bank, he would frequently have to turn away business that he knew Schwab’s competitors would grab in a heartbeat:

I was the front line, where issues escalated to me, and I would sometimes have to say, “We’re not doing that kind of business because it’s wrong for the customers and it’s wrong for us.” We had to turn away business we knew others would do because we focused on doing the right thing. People were coming to us for loans when they had no way to demonstrate their ability to pay us back. When we said, “We can’t give you this credit,” it was a tough conversation, but we did it. We turned them down, and some of them were clients who would say they would take their other business away from us, and some of them did. This upset our brokers. But I could already see the problems coming by 2006. Eighteen months later things imploded. There were companies that had been writing credit at all costs. Now we know what happened to them.

Despite the challenges of living in alignment, smart leaders recognize that acting consistently with values ultimately pays off. Spenser Segal is CEO of Actifi, which makes innovative software supporting the financial services industry. As Spenser tells it, living in alignment was key to helping his company navigate the 2008 economic downturn.

I really used the alignment model well in being really transparent with my people. Because of that, we haven’t lost any people. The senior management team and I bore the brunt of the financial implications. 2007 had been our best year ever, but then revenues dropped precipitously in 2008. Top line improved slightly in 2009 and the bottom line got much better, and now in 2010 we’re back. The congruency with values and goals that is the heart of living in alignment carried us through. Having weathered this makes us know we can get through anything.

Living in alignment is an approach to life, not just an approach to leadership. New Jersey mathematics professor Dr. Rich Bastian is passionate about teaching the next generation the skills needed to help the United States remain competitive in engineering and the sciences. Rich also is deeply devoted to his family and deliberately lives near his daughter and her three children. When he accepted a position at a local college, he made sure his schedule would enable him to align his actions with both of his passions. Four days a week he teaches classes and meets with students. Each Friday he spends time with one of his three grandchildren. He rotates their schedule so that at least once a month, each grandchild gets quality time with their granddad. In addition, Rich and his partner Louise host a weekly dinner for the kids, along with their mom and dad, Rich’s daughter Jessica, and her husband Erik.

Living in alignment may sometimes be difficult, but it doesn’t require superhuman acts. It is about the day-to-day steps we take to do what we need to do to reach our goals. One of our colleagues used to avoid speaking engagements before large audiences, preferring to work with people one on one or in small groups. Eventually, he realized that he could not effectively communicate his values and beliefs if he limited himself to small group presentations. So he joined Toastmasters, the worldwide organization that helps people develop their public-speaking abilities. Our friend’s desire to have a positive impact on the world led him to work on overcoming the anxiety of large group presentations.

Living in alignment is also not accidental. It requires doing things on purpose and for a purpose. Living in alignment is a two-part process: First, you build your own personal alignment model, by understanding what is inside each of these three frames:

• Moral Compass—What do you value, and what are your most important beliefs?

• Goals—What do you want to accomplish personally and professionally?

• Behavior—What actions will allow you to achieve your goals?

Then, after you build your own alignment model and know what should be in each frame, you work consciously and consistently to maintain alignment among your frames—simple, but as you might already suspect, far from easy.

Frame 1: Moral Compass

This frame contains the core moral principles and values that are the foundation of who we would ideally like to be as productive and fulfilled human beings. Principles and values overlap. They key difference is that principles are virtually universal: People everywhere tend to believe in their importance. As noted in Chapter 2, “Born to Be Moral,” these fundamental beliefs have been embedded in human society for so long that they are now widely recognized as universal. Four primary principles held in common globally are especially significant for effective leadership:

• Integrity

• Responsibility

• Compassion

• Forgiveness

It’s no coincidence that successful leaders, no matter what their style or personality, all seem to follow the beat of the same drum. They listen carefully to the call of moral principles that already lie within all of us. The leaders studied and interviewed for this book consistently demonstrated the importance of these principles. They were at their most effective when acting in alignment with principles. When they ignored them, business results suffered. Integrity and responsibility are essential minimum requirements for effective leadership. Lynn Sontag is President of Menttium Corporation, which helps companies nationwide coordinate mentoring programs for high potential emerging leaders. As Lynn points out, “Leaders who don’t step up and do the right thing will be left behind, because in today’s world with new technologies and social and business networking, there is no place to hide.” Compassion and forgiveness are equally important. They make the difference between a good leader and a great one. Consider the following example of the business value of compassion. Don Froude, president of Ameriprise Financial’s The Personal Advisor Group (TPAG) tells this story:

A year ago I became aware of a situation involving an advisor who was new to the firm and was behind his requirements to keep pace. When I talked to the advisor, I learned that his family responsibilities in the wake of his father’s recent death had made it impossible for him to dedicate enough time to his work. His leaders thought they had to follow the rules about dealing with every advisor, [no] matter what their situation. I told his leaders, “I can get a robot to just follow the rules. I need you to demonstrate some leadership judgment. That’s what I’m paying you for.” I’ve always believed that if someone doesn’t succeed, it’s because we have failed as their leaders. In this case, the leaders made an exception for this advisor, and that judgment paid off. The advisor is still with us and is now successful and meeting all of his performance requirements.

Values

Values differ from principles in that values are more personal beliefs about what is important to us as individuals. They are usually consistent with principles, and they enable us to put our own stamp on the meaning of the principles. For example, responsibility is a key principle, but our values help us choose how we individually express the principle of responsibility. We may value competence, challenge, or creativity. In each case, we can align our life choices both with those values and with the principle of responsibility. Will I be responsible by using my competence, by taking on challenges, or by finding creative solutions to areas such as work or family needs?

As we grew up, we learned a set of values, those qualities or standards that parents or caregivers considered important to our well-being and that of others. Over time, we came to adopt those values as guides to our own behavior. Families vary in the weight they place on certain values. Families often emphasize a variety of values, such as helping others, creativity, knowledge, financial security, or wealth accumulation. Early in our lives, we typically adopt our families’ values, and as we mature, we often add our own. By selecting, interweaving, and prioritizing our values, we define who we are—or at least who we want to be. Just as we recognize people by their physical characteristics such as hair color, height, or the way they laugh, we also come to know people by the values they embody. As we get to know friends or people with whom we work, we begin to recognize what means the most to them. Do they crave excitement, care about the environment, or seek status? We evaluate others based on how well our values mesh with theirs. You might value personal time for creative work more than social activities, while I might value relationships and family time more than professional recognition. We feel comfortable around people who share our most important values and often avoid those who don’t. If you value loyalty, for example, you may not like working with people who are self-serving.

Discovering Your Values

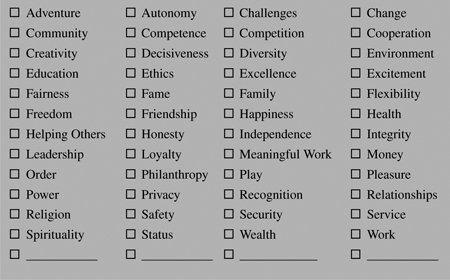

What is the set of values that anchors you? How would you want others to think of you? It’s no coincidence that successful leaders consistently make decisions aligned with their values. To act in alignment with our values, we must deeply understand what they are.

Try this: In the next 30 seconds, say out loud your five most important values. If you’re like most, you may be stuttering, or struggling to think. “Uh... family...financial security. Umm....” Our values are typically not top of mind. It’s so hard to figure out our values, that most values clarification exercises provide a “cheat sheet” list of common values. Steve Pavilla, a noted personal-development blogger, offers a list of 374 values on his web site. Author Doug’s company, the Lennick Aberman Group, created a pack of values cards, akin to trading cards, each of which names and explains a value. The following exercise, designed to help you become more aware of your values, is based on the Lennick Aberman Group values cards.

The Morality of Values

Not all values are created equal, as in the previous example. Without some context, values are neither moral nor immoral. It is only when we need to make decisions that have moral consequences that values take on moral significance. In the wake of the recent economic crisis, examples of values misalignment are plentiful. For example, what were heads of many United States banks and some other financial services companies thinking when in 2009 they accepted federal TARP funds but refused to use the cash infusion to ease lending for responsible businesses and qualified individuals?

When we make a decision that does not have any particular moral significance, as in deciding where to go on vacation, we might indulge our desire for adventure without a second thought. But when we make a decision that involves others, as is the case when considering a career move that would affect family members, the priorities we assign to our values must be consistent with universal principles. In that instance, we must honor the principle of responsibility. We may realize that our desire for adventure, growth, or more money would come at the cost of our responsibility to family.

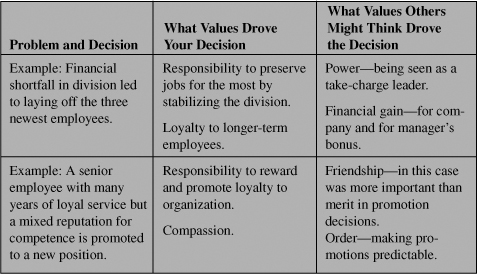

What Your Decisions Reveal About Your Values

Sometimes, we don’t actually value what we say we do. If, over time, you find yourself behaving inconsistently with your espoused values, you have a choice. You can learn to better align your behavior with your values by developing your moral and emotional competencies, or you may simply accept that you value some things that you did not realize were important to you. Either path is fine, as long as your actions don’t violate the universal principles.

This exercise can give you some insight into personal motivations that you might not have admitted to yourself before. Consider whether the values others might attribute to your decision may actually have some bearing on your choices.

Uncovering Values Conflicts

After you identify what you value, ideally and actually—look at your list of values and compare it with the universal principles. To ensure that your values are consistent with principles, ponder questions like these:

• Is my desire to achieve financial results so strong that I behave as if the end justifies the means?

• Does my desire for high achievement lead me to lack compassion for an employee whose family crisis takes him away from work at a critical time?

• Does my need for economic security discourage me from speaking out with integrity about an unethical corporate practice?

If you accept the importance of universal principles, you must—as a morally intelligent leader—reprioritize your values in line with the principles. We are not saying that you should not value what you value. But in some cases, it will be important to find a way to honor your values while upholding principles. You can honor both principles and personal values when you look for answers to questions such as, “How can I arrange my financial affairs so that I am protected if my ethical position gets me fired?” Or “How can I creatively allocate resources to preserve or improve group productivity while an employee is out on leave?”

It should be clear by now that values can be applied in a morally negative, neutral, or positive way. Consider, for example, power, which is a value important to many leaders, but many leaders often don’t want to admit that power motivates them. That’s because a desire for power often gets a bad rap. Power has the potential to be seductive, intoxicating, or lead to abuse. When power is abused, individuals and organization suffer. But like most other values, power can be leveraged for good or ill. Power used to promote universal principles is a tremendous force for organizational success and global advancement. As the late Robert F. Kennedy said

The problem of power is how to achieve its responsible use rather than its irresponsible and indulgent use—of how to get men of power to live for the public rather than off the public.1

Beliefs

Beliefs are the third component of our guidance system. For each of us, our beliefs are the “executive summary” of our individual world view. Beliefs represent our self-understanding about what we think is important and how we think of ourselves in relation to the outer world. They are the condensed version of our moral compass. Beliefs capture our larger list of principles and values in a streamlined form that is easier to communicate. Beliefs are the language we use to describe our values and our understanding of principles to ourselves and others. They connect our understanding of principles with our choice of values. You can’t actually know what your values are unless you can make a statement about what you believe.

Identifying Your Beliefs. You probably have 10,000 beliefs about yourself, your world, and human nature. But most people have a relatively short list of beliefs that they hold as their “convictions”—beliefs they use to guide decision making when the going gets rough. Many of these might even operate at an unconscious level most of the time, but with a little thought, most people can bring them up to the surface. What do you believe? You can use the following exercise to reflect on your top-ten beliefs.

By this point, you have identified the key elements of your moral compass. You have chosen the universal principles you embrace, you have articulated your values, and you have summarized your beliefs. Understanding your moral compass is essential for effective decision making. Living in alignment means that you hold yourself accountable for decisions consistent with your moral compass. But before you take action, you need to understand your goals and wants.

Frame 2: Goals

Scientists who study behavior tell us that humans have an innate need to make sense out of their lives. We constantly develop theories to explain why events happen as they do. We have an even deeper need to understand the meaning of our lives. How do our day-to-day events combine to create a coherent whole? What is the point of doing what we do? If we can begin to answer those questions, we have the beginning of our highest goal—our life’s purpose. Not everyone develops and follows a life purpose. People who were seriously brain-injured or severely neglected or abused might lack the capacity to formulate a meaningful purpose. But most of us are hungry to make sense out of our lives, so we create goals. Everyone’s life purpose is distinctively theirs, but each must be consistent with universal values, compassion, and forgiveness. Albert Schweitzer once said, “I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I do know: The only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.” Oprah Winfrey, who created one of the wealthiest entertainment empires in the United States, says this about purpose: “I’ve come to believe that each of us has a personal calling that’s as unique as a fingerprint—and that the best way to succeed is to discover what you love and then find a way to offer it to others in the form of service, working hard, and also allowing the energy of the universe to lead you.”2 Perhaps you already know your life’s purpose. Many of us have only a vague sense of it. Discovering your life’s purpose usually takes a period of reflection. One of the best resources for clarifying your life purpose can be found in Richard Leider’s book Repacking Your Bags: Lighten Your Load for the Rest of Your Life.3 Use the following purpose exercise to help provide you more insight about your life’s purpose.

Setting Purpose-Driven Goals

For each of us, our purpose is the major thing we want to accomplish in life. Our goals are more concrete things we’d like to accomplish to fulfill our purpose. The more aligned our goals are with our life purpose, the more effective we’ll be as a person and as a leader. An easy and powerful way to decide on your life goals is to use the Widdy Wiffy process Roy Geer developed and which he and Doug Lennick detailed in their book How to Get What You Want and Remain True to Yourself.5 Widdy Wiffy is the phonetic pronunciation of the acronym WDYWFY which stands for “What Do You Want for Yourself?” The title contains a bias: Getting what we want is good. Our goals can be at the same time “selfish” and morally aligned. Getting what one wants for oneself is a rightfully selfish process provided that what one wants is in alignment with our moral compass—our principles, values, and beliefs.

The WDYWFY process involves five profoundly simple steps:

• Have a goal (and write it down)

• Have a plan (and write it down)

• Implement the plan

• Control direction (keep score and when necessary redirect)

• Throw off discouragement (stay on track despite setbacks)

The importance of having specific goals is to ensure that what we actually do helps us create meaning out of our actions. Without goals, our ability to fulfill our life’s purpose would be a matter of chance. Setting deliberate goals allows us to satisfy our wants in a way that is aligned with our moral compass.

Not only does your goal frame help you satisfy your personal desires within a moral framework, paying attention to your goals also increases the odds that you will actually accomplish what you desire. If you don’t work on your goal frame, there is a random occurrence of achieving your goals. Career expert David Campbell made that point famously in his book If You Don’t Know Where You’re Going, You’ll Probably End Up Somewhere Else.6 Apparently, it’s not enough to have a set of goals in your head. You will boost your ability to achieve your goals when you write down your goals and your plans to achieve them. Why do written goals have such a positive impact? The most basic reason is that we tend to forget things. The physical process of writing helps our brain retain and recall the things we want to accomplish. When we write down goals, we have an opportunity to reflect carefully on what we actually want and consider the best ways to accomplish them. When we record our goals, we can use our list as a reminder to stay on track. The process of writing down goals enhances our commitment and capacity to be responsible for the choices we make. We have all known of highly intelligent individuals who never lived up to their potential. Goal setting can help you leverage the power of your moral intelligence to have a positive impact on your organization and the world.

Why Leaders Love Goals

Every effective leader we know has crystal clear goals. Goals are crucial to effective leadership because they move you beyond awareness or good intentions to specific actions. Effective leaders accept responsibility for their choices by “getting on the record” with their goals. Effective leaders have goals that they truly care about. They also encourage their followers to develop personally satisfying goals. One of the most powerful motivational tools of a good leader is to show that you care about the wants and goals of the people who work with you. Employees with that rare boss who shows genuine interest in their goals—and who spends time helping them chart a course to reach those goals—respond with loyalty and commitment.

Actifi’s Spenser Segal is one such leader. “I take the WDYWFY thing seriously, and I really know what my people want. I use the alignment model to learn what people value and what their goals are. Money is never most important to my people, but meaningful work and making a difference is.” Spenser’s focus on his people’s goals contributed greatly to the company’s capability to weather the economic downturn. Although Actifi restructured and deferred compensation, it did not lose any employees during the downturn, and the company has emerged stronger than ever.

Your Goals

What exactly do you want for yourself? What are your goals? The majority of us want to play the roles we have in life well. Most people who are parents want to be good at it. Even terrible parents want to be good at it. There are few of us who don’t care about how we perform. How many of you want to be part of a family that you are proud of? How many of you want to be part of an organization that you are proud of? What do you have to do to accomplish that?

Put It in Writing

Whether you are developing new goals or reinforcing long-standing goals, writing your goals down here can make them more real. Keep in mind that there are two kinds of goals. Some goals are a state of being goal, such as “I have three children. I want to be a good father now.” Another type of goal is a future-based goal, for example, “I want to retire within five years” or “I want to lose weight.” We recommend that you include goals of both types. We also recommend that you be clear with yourself about goals in three different areas: professional, personal, and self-development.

You don’t need to abandon any goal that would make you wildly happy. But you will find that your overall happiness and effectiveness will be enhanced if each of your goals is strongly aligned with your moral compass.

Frame 3: Behavior

The behavior frame puts the “living” in “living in alignment.” Your behavior frame represents what you actually do, including your thoughts, emotions, and outward actions. Your behavior frame takes your values and beliefs from frame 1, and your goals from frame 2, and makes them real. We cannot be successful leaders—or human beings—unless we embrace principles and values, set clear goals, and act accordingly. Although we don’t get to choose our emotions, we do get to choose our thoughts and actions. And wonderfully, we discover the thoughts and actions we choose actually do influence the emotions we experience. When we make choices that are not in alignment, we may give ourselves the benefit of the doubt, but our families, our colleagues, and our financial institutions do not. So keeping our behavior in alignment with our moral compass and goals is an essential task of a good leader.

Thoughts

What makes thoughts part of our behavior frame? Psychologists recognize thoughts as a form of cognitive behavior. Thoughts profoundly affect our emotions and our outward behavior. And the trouble with thoughts is that they often mask as facts. Even when we think we are being logical and objective, often that’s not the case. Most of us are biased about many things, and some of those biases get baked into our logic. For example, if I’m an avid fan of my local football team that just made it into the Super Bowl, I might find it easy to justify spending a few thousands of dollars to travel across the country to see the big game. I may unwittingly “underestimate” the cost of the trip, because I really want to go. And I might justify the expense even if it will add to my credit card debt or cause me to miss my daughter’s birthday.

We also tend to rely on rules of thumb, or mental shortcuts for making decisions. One of my rules of thumb might be “only hire people who graduated from Ivy League colleges.” But how effective is my rule of thumb? What are the consequences of taking a mental shortcut when making hiring decisions? My rule of thumb might help me shrink the pile of resumes sitting on my desk. But by routinely ignoring potential employees who didn’t attend certain schools, I probably lost the opportunity to hire some talented people who could have made significant contributions to my organization.

So always question your logic. It’s important to think through your choices relative to your moral compass and your goals. Even careful questioning won’t mean you will always be right. There is no silver bullet for making optimal leadership choices. But challenging your logic can make it more likely that you make the most of all your cognitive and technical abilities in support of your organization.

Emotions

Everyone has them, even the most rational and composed of us. Emotions have a strong influence on our view of financial situations and our response to them. That’s because your brain is hard-wired to encourage emotional decision making. When we’re in the presence of a strong external event—say a looming merger or downsizing—the part of our brain that processes emotions gets the message first. In other words, the triggering event stimulates our emotional intelligence before it stimulates our cognitive intelligence. Our emotional intelligence sacrifices accuracy for speed. We act on a flood of emotions—fear or excitement before the logical part of our brains gets a chance to evaluate the situation objectively. Why does our brain do something that can make it so difficult to apply our moral intelligence? As we learned in Chapter 2, our brain evolved to promote our physical survival, to keep us out of danger, and to encourage us to nourish ourselves. When we sense danger, our brain’s “danger system” activates. It immediately sets off a whole host of physiological changes that help us get away from the source of the danger. Our danger system turns our analytical centers off, as if to say, “You don’t have time to figure out the nuances of this situation. Just get out of here!” But even when we’re not in physical danger, our automatic danger response still kicks in with a flood of emotions that are better suited for escaping from a bear than dealing with a business crisis. When we truly are in a life-threatening situation, we need a speedy response. It saves us. But business challenges, although often emotionally painful, are not life threatening. So sacrificing the accuracy of our thinking brain for the speed of our emotional brain begins to work against us.

Now take the case of a business opportunity that seems promising, not scary. As soon as we feel stimulated by such a positive opportunity, our brain’s reward system turns on. It secretes a chemical called dopamine, which gives us a sense of security and confidence that enables us to pursue opportunities. But when our reward system is turned on, our danger system is turned off. So we can’t notice the risk that may be involved.

Keep in mind that emotions, in and of themselves, are neither good nor bad. They are simply emotions. But because strong emotions, whether positive or painful, can get in the way of effective decisions, emotions must be managed. The most effective leaders know how to regulate their own and others’ emotional responses in a way that promotes a positive and high-performing work environment. If leaders lack emotional control or insight into the emotional needs of their followers, the work environment suffers.

Earlier in her career, when Menttium President Lynn Sontag was a senior leader in executive development at a Fortune 100 company, she once made the mistake of transferring a call from an irate executive spouse to her boss. The caller, who had considerable clout, was having a temper tantrum about something that the organization wouldn’t as a matter of policy give her. Lynn realized too late that she should have prepared her boss for the call so that he wouldn’t get stuck in a political bind. She still has vivid memories of his reaction and the impact on her subsequent performance:

I can visualize the whole thing. My office was kitty corner from the executive director, and I could see his expressions as he talked to her, and it was pretty visual. His door was closed, but I could see him through his window, and I knew where he was heading as soon as he opened the door. He blew up in front of me and everyone else around. The next day he calmed down, and we walked through it and processed it so that it wouldn’t happen again. We got through it, but I was derailed on a personal level for a long time. I still had to work with the woman for another year and a half. It took me more than a couple months to let go. It hit me right where my confidence was. I didn’t trust my own judgment, and I became unwilling to make decisions without checking with a lot of people first.

Actions

We all know that actions speak louder than words. Having a moral compass and admirable goals is worthless unless we do what it takes to make them real. Failure to act in concert with our values and goals is worse than worthless. It is a failure of the core principle of responsibility. It does harm to everyone and everything we care about—family, co-workers, and community. And it does us harm. Often we lose something extremely precious—other people’s trust and respect.

In Search of Alignment

Now that you see the canvas inside each of your frames, how do you keep your frames aligned? Most people agree that the notion of living in alignment makes sense. If that’s true, then why is living in alignment so hard? Why is it so difficult to use our inborn moral intelligence to make smart choices that support our values and goals? In the next chapter, you begin to discover the obstacles to living in alignment—and the secrets for overcoming them.

Endnotes

1. Robert F. Kennedy (1925–1968), “I Remember, I Believe,” The Pursuit of Justice, 1964.

2. Oprah Winfrey, O The Oprah Magazine, September 2002.

3. Richard J. Leider. Repacking Your Bags: Lighten Your Load for the Rest of Your Life, San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1995.

4. Based on an exercise in Richard J. Leider. Repacking Your Bags: Lighten Your Load for the Rest of Your Life, San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1995.

5. Doug Lennick and Roy Geer. How to Get What You Want and Remain True to Yourself, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Lerner Publications Company, 1989.

6. David Campbell. If You Don’t Know Where You’re Going, You’ll Probably End Up Somewhere Else, Notre Dame, Indiana: Ave Maria Press, 1990.