4. Staying True to Your Moral Compass

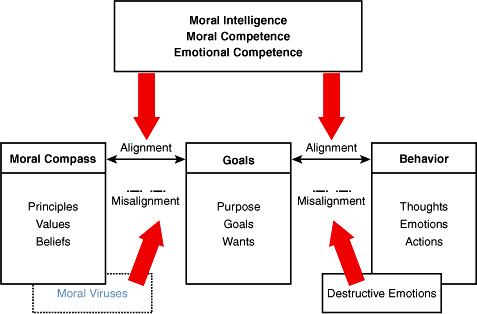

Knowing who you want to be—an honest, responsible, and compassionate leader—is one thing. Knowing how to become your best self is another. Actually doing what you know you should is still another matter. That is the essence of alignment, a shorthand term that means “your goals and your behaviors are consistent with your moral compass.” We need three qualities to help us keep us in alignment:

• Moral intelligence—Part of us that shapes our moral compass and ensures that our goals are consistent with our moral compass

• Moral competence—Ability to act on our moral principles

• Emotional competence—Ability to manage our and others’ emotions in morally charged situations

Moral intelligence. Can you interpret this formula?

Here’s a hint: The equation here represents the “fundamental theorem of calculus.” It expresses that differentiation and integration are inverse operations of each other. Now do you understand? If you’re like most people, that explanation helps a little, but not much. You can tell that the diagram is a mathematical equation, and you’ve heard of calculus, but you might not understand or remember the distinction between differentiation and integration. For people who are mathematically inclined, the fundamental theorem of calculus probably looks as simple to them as 2 + 2 = 4 does to the rest of us. A complicated equation makes sense to the mathematician because she has two qualities—mathematical intelligence (basic aptitude) and mathematical competence (learned skills). Mathematical intelligence isn’t sufficient to be good at math, but no amount of practice can make you a good mathematician if you don’t have an underlying aptitude. Moral intelligence is another kind of aptitude. Without it, no amount of training can turn us into moral leaders. Recall the brain-injured toddlers. No matter how hard their parents tried to instill positive values, they simply lacked the basic neurological equipment to distinguish between right and wrong.

Moral intelligence is our basic aptitude for moral thought and action. We call on it to make sense out of moral principles (the “fundamental theorems” of morality). Moral intelligence enables us to develop moral values and beliefs and to integrate those values and beliefs into a coherent moral compass. Because it’s the part of us that knows what’s right, we use it to ensure that our goals and behavior are in alignment with our moral compass. Like a smoke detector, our moral intelligence sounds the alarms when our goals or actions move out of synch with our moral compass.

When Charlie Zelle was a young New York investment banker, his family’s Midwestern transportation and real-estate business went into a financial tailspin. After he returned home to help save the business, company lawyers called a meeting of management and key family shareholders to decide the firm’s fate. When lawyers and family members began to talk, Charlie was astonished at how glib they all seemed. It was clear that they had already decided to throw in the towel and no one seemed all that upset about it. Charlie got angry—his moral intelligence alarms were deafening. He thought shutting down the company was unfair and a selfish move on the part of his family. If the company folded, 500 employees would lose their jobs, and people in the community would lose access to the public transportation they provided.

Moral competence. Although moral intelligence involves knowing what to do, moral competence is the skill of actually doing the right thing. How do we do what we know is right? How do we do the right thing even when we are scared or pressured? For that, we need moral competence. We need it to understand what goals will enable us to be true to our principles, and we need moral competence to act in alignment with our values and beliefs. Charlie Zelle’s moral intelligence told him that it was selfish for his family to simply cut their losses at the cost of fairness to employees and the community. But it took moral competence for Charlie to act on that awareness. He was just a kid, but fueled by his anger and encouraged by a mentor, Charlie found his voice. He found some investors, formed a new company, bought the buses back from bankruptcy court, and rehired all the employees from his family’s old company. The odds of success were low, but with the help of a senior vice president who knew and loved the business, they survived. Fifteen years later, Charlie’s company, Jefferson Bus Lines, is a thriving regional bus operator.

Emotional competence. To live in alignment, we also need to be emotionally competent. Emotional competence helps us manage our emotions and the emotional quality of our relationships with others. It’s almost impossible to be morally competent without being emotionally competent as well. For example, most of us value honesty and most of us have the moral competence to be truthful. After all, we’ve told the truth countless times. But if we’re such experts at telling the truth, why then do many of us lie so often? A UK women’s magazine survey, for instance, found that 94% of women admitted that they tell lies, half of them lying on a daily basis. Emotional competence helps us answer questions like these:

• What makes it hard to tell the truth in a particular situation?

• How will others act if I tell the truth or fail to tell the truth?

• How can I tell the truth in a way that will preserve my relationships with others?

Emotional competence enables us to understand our own emotions, especially those that can get in the way of doing the right thing. Emotional competence also helps us understand and respond intelligently to the emotions of others. That ability to respond to others’ emotional needs in turn creates a positive work environment in which people feel safe enough to do what is morally right—and not incidentally, perform at their best.

When leaders lack emotional competence, they create a negative climate that encourages self-protection rather than integrity. Lori Kaiser, Pacific Northwest Managing Partner at Tatum LLC, ran into an emotionally incompetent manager at a previous company where she had worked early in her career. He was a foul-mouthed senior manager who routinely harassed his juniors. Everyone knew he was obnoxious, but no one called him on it. Lori tolerated it for years. Then while on maternity leave, she realized how great it felt to be away from him. When she returned from leave, she took advantage of her newfound status as the company’s most senior woman to draw a line in the sand. Lori told her superiors she would return only if she did not have to work with the obnoxious manager. Her superiors agreed but did nothing to correct his behavior. Other employees, in part weary of dealing with him, began to leave the company. Only then did management begin to pay attention to his behavior, but by then, they had lost some valuable people—largely because of the negative environment created by one emotionally incompetent leader.

Lori faults herself for failing to act sooner. She tolerated his negative behavior for a long time because the company paid her well to do the kind of work she wanted to do. Though she was not the source of a negative environment, she believes she was partially responsible for allowing it to continue. “Even though I may be able to tolerate difficult people,” says Lori, “the people who follow me need someone who can speak up. If I condone bad behavior in front of junior men or women, it’s unacceptable. Now I speak up for all of the people who are junior to me and can’t speak up, even if it makes me look like I’m not one of the gang.”

Staying aligned. When you consistently use your moral intelligence, moral competence, and emotional competence, you will find that you are spending more and more time living in alignment with your moral compass. When your three frames are in synch, you feel as though you are “in the zone,” and your creativity and performance are at their best. When you are in a leadership role, your state of alignment is palpable and appealing to followers. Your state of alignment contributes to an emotionally positive and high-performing work environment for others.

Think of the leaders who have inspired you the most. They are almost invariably those who consistently demonstrate their commitment to principles that you also believe in. Lynn Fantom, CEO of ID Media, says of her former boss, David Bell, now Chairman Emeritus of parent company Interpublic, “I would do anything for him because he shows respect to me and everyone in the company by doing simple things like sending short email messages of appreciation.”

Moral misalignment. The most successful leaders spend the majority of their time in alignment. But all of us experience times when it is hard to stay in alignment, times when our moral intelligence doesn’t seem to be having an impact on what we want or what we actually do. Instead of being connected to our ideal selves—who we would like to be at our best—we disconnect from our moral compass. Misalignments don’t usually happen because we lack moral or emotional skills. Typically, they occur because moral viruses or destructive emotions are interfering with our ability to use moral and emotional competencies that we have successfully used in the past.

Moral viruses are disabling and inaccurate negative beliefs that interfere with alignment (see Figure 4.1). Moral viruses infect our moral compass and lead us to adopt goals that are inconsistent with our moral compass.

Figure 4.1 Alignment Model

Diagnosing a moral virus. Moral viruses are unfounded negative beliefs that are in conflict with universal principles. Like computer viruses that infect a computer’s operating system, moral viruses invade your moral compass and often lead to breakdown. Moral viruses remind us of computer “adware,” the insidious advertising software programs that are installed on your computer via the Internet without your consent. Suddenly, your computer desktop is overwhelmed by pop-up ads, and when you try to find and delete the adware program, you find it’s difficult. Your antivirus software probably will not work. The unwanted program has the capability to hide its files and to resist attempts to remove it. Like adware, moral viruses sneak into your moral operating system. They hide themselves well: At a conscious level, you may articulate a set of principles, values, and beliefs that are admirable, without realizing that you are secretly harboring an unsavory belief that affects the quality of your goals. Your “official” goals are in alignment with your moral compass. But without your awareness, you have adopted some “unofficial” goals that are at odds with your moral compass. The end result is that you do things that are inconsistent with your moral compass, and you are probably pretty confused about the reasons why.

Consider the experience of John Simmons (pseudonym), founding partner in a growing professional services firm. He was attending a partner’s meeting for his firm. Compensation was on the agenda, and during the discussion, John found himself insisting that his fellow owners adopt a lot of legalistic provisions that he thought necessary to ensure he would be compensated fairly for all his efforts. During the discussion, John became increasingly rigid, frustrating his partners. Finally, they told him he was acting as if they were his enemies rather than people who shared his goals. John knew instantly they were right, but it took a few hours of reflection to figure out why he had behaved with such suspicion.

John explains, “When I was about four years old, I got into an argument with my older brother and I bit him! My father insisted that I apologize. I refused. Before I realized the stakes of the game I was playing, my father said, “If you don’t apologize, you can’t be a part of this family.” He proceeded to take me about a half a mile away from our farmhouse and dump me off in the pasture. I recall running back home, crying as I ran. My false conclusion was that when it comes to basic needs like personal safety you really can’t trust anyone, even those close to you. Even people who have never actually taken advantage of you might still turn on you in unpredictable ways. Always be on guard!”

When John uncovered his “moral virus,” he went back to his fellow owners to own up to the negative beliefs that had infected his moral compass and disrupted their meeting.

Common Moral Viruses

• Most people can’t be trusted.

• I’m not worth much.

• I’m better than most other people.

• Might makes right.

• If it feels good, do it.

• My needs are more important than anyone else’s.

• Most people care more about themselves than anyone else.

• People of other (races, religions, and nationalities) are not as good as people of my (race, religion, and nationality).

Dealing with moral viruses. A good way to manage moral viruses is to scan for them in your thoughts. To figure out what you are thinking, tune in to your “self talk”—the continuous internal conversation that you have with yourself. Like computer antivirus software that periodically scans for new viruses, you should regularly scan your self talk to stay aware of the internal beliefs that are influencing your daily actions. In addition to regular moral virus scans, we recommend that you scan your self-talk for possible moral viruses whenever you experience strong emotion, either positive or negative. Because thoughts and emotions mutually influence each other, it is especially important to understand the beliefs that may be the root cause of uncomfortable emotions.

Disabling a moral virus. When you have detected a moral virus in your thoughts, you have the opportunity to replace it with a thought or belief consistent with your moral compass. Countering a moral virus is effective in the moment, but it is not a permanent fix. Moral viruses sometimes act like certain biological viruses that lurk indefinitely within us. For example, the virus that causes shingles, a relative of the chicken pox virus, is a chronic virus. After an outbreak of shingles, the virus doesn’t die. It retreats to the base of a bundle of nerves, where it lies dormant unless the affected person’s immune system is weakened by another illness, allowing the old virus’ symptoms to reappear. Similarly, when we are under stress, the symptoms of a moral virus can once again resurface. In the example just described, John Simmons figured out how he had been infected by a moral virus, but he knows he may run into the same virus in the future. John is not “cured,” but his awareness can help him to recognize moral virus symptoms and move quickly to minimize its negative affects in the future.

Because none of us had a perfect upbringing, most of us will have at least one moral virus lying in wait to overtake us in a difficult moment. That is why it is important to scan our thoughts regularly and why it is necessary to actively remind ourselves of our more desirable Frame 1 beliefs. A good rule of thumb is this: When you find yourself doing something that is puzzling to you when you say to yourself, “I don’t know why I behaved that way...,” you are likely dealing with some sort of moral virus. That is a good signal to talk it out with a good friend or trusted advisor. Like a virus that thrives in the dark, moral viruses brought out into the light often wither and die.

Destructive emotions. Destructive emotions are the most common culprits in keeping us from acting consistently with our goals. Emotions such as greed, hate, or jealousy are powerful and can overwhelm our normal ability to act in a morally and emotionally competent manner. It is human nature to experience periodic emotional “breakdowns”—not usually the kind that sends us off for a long rest cure, but the more commonplace stresses that can lead us to become emotionally overwhelmed. Our moral compass is intact, and our goals are clear, but in the heat of the moment, we act in a way completely inconsistent with what we say we want. We lose control and allow destructive emotions to take hold. Greed is an especially destructive emotion, one that likely lies at the heart of the corporate accounting scandals of the early 2000s and the more recent economic crisis of the late 2000s. It’s hard to imagine that any of the executives implicated for accounting or securities fraud in the last decade needed more money than they already had. For an executive in the throes of greed, however, enough is never enough. We’re all too familiar with the impact of greed-driven schemes—employees deprived of jobs and retirement funds, shareholders betrayed, homeowners being evicted, and companies going out of business.

Managing destructive emotions. There will always be occasions when you feel negative emotions. Your goal should not be to eliminate all traces of negative feelings from your experience, but rather to develop the emotional control to manage destructive emotions so they don’t derail you. Managing destructive emotions is vital to a successful leadership career because left unchecked, they are a frequent cause of career derailment among executives. A senior manufacturing executive interviewed for this book notes the importance of managing potentially destructive emotions: “Someone will renege on something or not do something they promised, or they’ll misrepresent things and I just want to get even. I’ve had to develop a lot of self-control. I don’t often lose my temper and if I do, I try to do it behind closed doors with my team. So the challenge is treating people the way I’d like to be treated versus the way I’d like to treat them because they screwed me. I don’t feel like I’ve had to be extremely sensitive so much as I’ve needed to control my revenge motive and be professional.”

A powerful antidote to negative emotions is the deliberate cultivation of a positive emotional state. Controlling emotions must come from within. No one having a temper tantrum—child or adult—wants to be told by others to “calm down.” Fortunately, we can learn how to short-circuit highly charged negative emotions. Deep breathing exercises, deep muscle relaxation exercises, and meditation, are just a few of the scientifically documented ways to produce more positive emotional states.1 Depending on your personal preferences, activities as varied as hobbies, community service, spending time in nature or with family members, even washing the dishes can trigger a positive mental state. They work because you cannot have two incompatible physiological states at the same time. You cannot be angry when you are happy. You cannot be anxious when you are calm. Regular practice of your preferred technique is key to your ability to manage your emotions. Through practice, you can create a calm and peaceful internal state that automatically kicks in when you need it. When you deliberately cultivate a positive and relaxed emotional state, you can call upon that positive state whenever a destructive emotion is beginning to take hold.

The experiential triangle. We each operate within an experiential triangle of thoughts, emotions, and behavior, all of which mutually influence one another. Although we discussed moral viruses and destructive emotions as though they were separate phenomena, in reality, they are typically found together and often reinforce the negative effects of each. Emotions are usually the product of our thoughts. When we admire someone, for example, our happiness in seeing that person stems not from their physical existence, but because of the ideas we have about them. Similarly, when we are in the throes of a destructive emotion, we have a reason. Our negative feeling is prompted by some thoughts or beliefs we have about the situation we are in. You think, “I knew I couldn’t trust them,” or “I should have gotten more,” and you feel terrible. The worse you feel, the more likely it is that a moral virus has invaded your belief system. Destructive emotions such as anger and jealousy are the “fever” that often accompanies a moral virus. But emotions also stimulate thought processes. When a destructive emotion overcomes you, it can negatively influence the way you think about yourself or others, thereby causing a moral virus. Finally, our thoughts and emotions affect our behavior. The behavioral impact of moral viruses and destructive emotions is widespread and obvious. For a leader, the effects of moral viruses and destructive emotions can be career-ending. At the very least, your performance suffers along with that of your co-workers.

Consider these contrasting experiential triangles.

Suppose, on the other hand, that you found yourself unable to confront your boss. Would it be because you were unaware that what she was doing was wrong, or because you did not know how to raise the issue? Probably not. More likely, your failure to act would be the result of your beliefs about the situation. Your beliefs create a context, or framework, for deciding how to respond to your boss’s actions. You might then be operating in an experiential triangle that operates something like this:

In this example, we can detect a moral virus in the belief that one should “mind one’s own business,” coupled with the belief that others will do you harm if you challenge their negative behavior. This moral virus is likely contaminating more positive beliefs about human nature and our responsibility to do what is right. But a moral virus can deactivate positive beliefs in a difficult moment, replacing them with negative beliefs about other’s motives and our own responsibility. In this example, we can also see the destructive power of emotions such as fear and anxiety that further reinforce negative beliefs and the misguided actions that result.

Preventive maintenance. Staying in alignment requires regular tune-ups to monitor and prevent damaging effects of moral viruses and destructive emotions. But most important, alignment depends on continuously developing our moral and emotional competence. But how? What are the practical day-to-day actions we must take to stay in alignment? For that, we need to be proficient in a group of specific moral and emotional skills—as you see in the next several chapters of this book.

Endnote

1. Many techniques for inducing positive emotional states can be found in Herbert Benson, M.D. and William Proctor’s The Break-Out Principle, New York: Scribner, 2003.