Chapter One. What Is Lean and Why Is It Important?

Lean creates value. And it does that by creating competitive advantages that better satisfy the customer.

Joe Stenzel1

1. Joe Stenzel, Lean Accounting: Best Practices for Sustainable Integration (John Wiley & Sons, 2007), Kindle loc. 1317–18.

Lean Integration is not a one-time effort; you can’t just flip a switch and proclaim to be done. It is a long-term strategy for how an organization approaches the challenges of process and data integration. Lean can and does deliver early benefits, but it doesn’t end there. Lean principles such as waste elimination are never-ending activities that result in ongoing benefits. Furthermore, some Lean objectives such as becoming a team-based learning organization with a sustainable culture of continuous improvement may require years to change entrenched bad habits.

Before you start on the Lean journey, therefore, you should be clear about why you are doing so. This chapter, and the rest of the book, will elaborate on the technical merits and business value of Lean Integration and how to implement a program that delivers on the promise. Here is a summary of why you would want to:

• Efficiency: Lean Integration teams typically realize 50 percent labor productivity improvements and 90 percent lead-time reduction through value stream mapping and continuous efforts to eliminate non-value-added activities. The continuous improvement case study (Chapter 5) is an excellent example.

• Agility: Take integration off the critical path on projects by using highly automated processes, reusable components, and self-service delivery models. The mass customization case study (Chapter 8) demonstrates key elements of this benefit.

• Data quality: Establish one version of the truth by treating data as an asset, establishing effective information models, and engaging business leaders and front-line staff to accept accountability for data quality. The Smith & Nephew case study (Chapter 6) shows how this is possible.

• Governance: Measure the business value of integration by establishing metrics that drive continuous improvement, enable benchmarking against market prices, and support regulatory and compliance enforcement. The integration hub case study (Chapter 10) is an excellent example of effective data governance.

• Innovation: Enable staff to innovate and test new ideas by using fact-based problem solving and automating “routine” integration tasks to give staff more time for value-added activities. The Wells Fargo business process automation case study (Chapter 9) is a compelling example of automation enabling innovation.

• Staff morale: Increase the engagement and motivation of IT staff by empowering cross-functional teams to drive bottom-up improvements. The decentralized enterprise case study (Chapter 12) shows how staff can be engaged and work together across highly independent business units.

Achieving all these benefits will take time, but we hope that after you have finished reading this book, you will agree with us that these benefits are real and achievable. Most important, we hope that you will have learned enough to start the Lean journey with confidence.

Let’s start by exploring one of the major challenges in most non-Lean IT organizations: the rapid pace of change and surviving at the edge of chaos.

Constant Rapid Change and Organizational Agility

Much has been written about the accelerating pace of change in the global business environment and the exponential growth in IT systems and data. While rapid change is the modern enterprise reality, the question is how organizations can manage the changes. At one end of the spectrum we find agile data-driven organizations that are able to quickly adapt to market opportunities and regulatory demands, leverage business intelligence for competitive advantage, and regularly invest in simplification to stay ahead of the IT complexity wave. At the other end of the spectrum we find organizations that operate at the edge of chaos, constantly fighting fires and barely in control of a constantly changing environment. You may be somewhere in the middle, but on balance we find more organizations at the edge of chaos rather than at the agile data-driven end of the spectrum.

Here is a quick test you can perform to determine if your IT organization is at the edge of chaos. Look up a few of the major production incidents that have occurred in the past year and that have been closely analyzed and well documented. If there haven’t been any, that might be a sign that you are not on the edge of chaos (unless your organization has a culture of firefighting without postmortems). Assuming you have a few, how many findings are documented for each production incident? Are there one or two issues that contributed to the outage, or are there dozens of findings and follow-up action items?

We’re not talking about the root cause of the incident. As a general rule, an analysis of most production incidents results in identifying a single, and often very simple, failure that caused a chain reaction of events resulting in a major outage. But we also find that for virtually all major outages there is a host of contributing factors that delayed the recovery process or amplified the impact.

Here is a typical example: An air conditioner fails, the backup air conditioner fails as well, the room overheats, the lights-out data center sends an automatic page to the night operator, the pager battery is dead, a disk controller fails when it overheats, the failure shuts down a batch update application, a dependent application is put on hold waiting for the first one to complete, an automatic page to the application owner is sent out once the service level agreement (SLA) for the required completion is missed, the application owner quit a month ago and the new owner’s pager has not been updated in the phone list, the chain reaction sets off dozens of alarms, and a major outage is declared which triggers 30 staff members to dial into the recovery bridge line, the volume of alarms creates conflicting information about the cause of the problem which delays problem analysis for several hours, and so on and so on.

Based on our experience with hundreds of similar incidents in banks, retail organizations, manufacturers, telecommunications companies, health care providers, utilities, and government agencies, we have made two key observations: (1) There is never just one thing that contributes to a major outage, and (2) the exact same combination of factors never happens twice. The pattern is that there is no pattern—which is a good definition of chaos. Our conclusion is that at any given point in time, every large IT organization has hundreds or thousands of undiscovered defects, and all it takes is just the right one to begin a chain reaction that results in a severity 1 outage.

So what does this have to do with Lean? Production failures are examples of the necessity of detecting and dealing with every small problem because it is impossible to predict how they line up to create a catastrophe. Three Mile Island is a classic example. Lean organizations relentlessly improve in numerous small steps. A metaphor for how Lean organizations uncover their problems is to imagine a lake with a rocky bottom, where the rocks represent the many quality and process problems affecting their ability to build the best products for their customers. Metaphorically, they “lower the water level” (reduce their inventories, reduce their batch sizes, and speed up reconfiguring their assembly lines, among other techniques) in order to expose the rocks on the bottom of the lake. Once the “rocks” are exposed, they can focus on continually improving themselves by fixing these problems. Integration systems benefit from “lowering the water level” as well. Every failure of a system uncovers a lack of knowledge about the process or its connections. Problem solving is learning more deeply about our processes, infrastructure, and information domains.

We are of the opinion that the edge of chaos is the normal state of affairs and cannot be mitigated purely by technology. The very nature of systems-of-systems is that they emerge and evolve without a complete (100 percent) understanding of all dependencies and behaviors. There are literally billions of permutations and combinations of the internal states of each software component in a large enterprise, and they are constantly changing. It is virtually impossible to test all of them or to build systems that can guard against all possible failures. The challenge is stated best in remarks by Fred Brooks in The Mythical Man-Month: “Software entities are more complex for their size than perhaps any other human construct, because no two parts are alike. . . . If they are, we make the two similar parts into one, a subroutine.” And “Software systems have orders of magnitude more states than computers do.”2

2. Frederick P. Brooks, Jr., The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering, Anniversary Edition (Addison-Wesley, 2004), pp. 182, 183.

So what is the solution? The solution is to perform IT practices such as integration, change management, enterprise architecture, and project management in a disciplined fashion. Note that discipline is not simply a matter of people doing what they are supposed to do. Lack of discipline is not their problem; it is the problem of their managers who have not ensured that the work process makes failure obvious or who have not trained people to respond to revealed failures first with immediate containment and then with effective countermeasures using PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, and Act).

To effectively counter the effects of chaos, you need to approach integration as an enterprise strategy and not as an ad hoc or project activity. If you view integration as a series of discrete and separate activities that are not connected, you won’t buy into the Lean concept. By virtue of the fact that you are reading this book, the chances are you are among the majority of IT professionals who understand the need for efficiency and the value of reuse and repeatability. After all, we know what happens when you execute project after project without a standard platform and without an integration strategy; 100 percent of the time the result is an integration hairball. There are no counterexamples. When you allow independent project teams to choose their own tools and to apply their own coding, naming, and documentation standards, you eventually end up with a hairball—every time. The hairball is characterized by an overly complex collection of dependencies between application components that is hard to change, expensive to maintain, and unpredictable in operation.

If for whatever reason you remain fixed in the paradigm that integration is a project process as opposed to an ongoing process, there are many methodologies to choose from. Virtually all large consulting firms have a proprietary methodology that they would be happy to share with you if you hire them, and some of them will even sell it to you. Some integration platform suppliers make their integration methodology available to customers at no cost.

But if you perceive the integration challenge to be more than a project activity—in other words, an ongoing, sustainable discipline—you need another approach. Some alternatives that you may consider are IT service management practices such as ITIL (Information Technology Infrastructure Library), IT governance practices such as COBIT (Control Objectives for Information and Technology), IT architecture practices such as TOGAF (The Open Group Architecture Framework), software engineering practices such as CMM (Capability Maturity Model), or generalized quality management practices such as Six Sigma. All of these are well-established management systems that inherently, because of their holistic enterprise-wide perspective, provide a measure of sustainable integration. That said, none of them provides detailed practices for sustaining solutions to data quality or integration issues that emerge from information exchanges between independently managed applications, with incompatible data models that evolve independently. In short, these “off the shelf” methods aren’t sustainable since they are not your own. Different business contexts, service sets, products, and corporate cultures need different practices. Every enterprise ultimately needs to grow its own methods and practices, drawing from the principles of Lean Integration.

Another alternative to fixing the hairball issue that is often considered is the enterprise resource planning (ERP) architecture, a monolithic integrated application. The rationale for this argument is that you can make the integration problem go away by simply buying all the software from one vendor. In practice this approach doesn’t work except in very unique situations such as in an organization that has a narrow business scope and a rigid operating model, is prepared to accept the trade-off of simply “doing without” if the chosen software package doesn’t offer a solution, and is resigned to not growing or getting involved in any mergers or acquisitions. This combination of circumstances is rare in the modern business economy. The reality is that the complexity of most enterprises, and the variation in business processes, simply cannot be handled by one software application.

A final alternative that some organizations consider is to outsource the entire IT department. This doesn’t actually solve the integration challenges; it simply transfers them to someone else. In some respects outsourcing can make the problem worse since integration is not simply an IT problem; it is a problem of alignment across business functions. In an outsourced business model, the formality of the arrangement between the company and the supplier may handcuff the mutual collaboration that is generally necessary for a sustainable integration scenario. On the other hand, if you outsource your IT function, you may insist (contractually) that the supplier provide a sustainable approach to integration. In this case you may want to ask your supplier to read this book and then write the principles of Lean Integration into the contract.

In summary, Lean transforms integration from an art into a science, a repeatable and teachable methodology that shifts the focus from integration as a point-in-time activity to integration as a sustainable activity that enables organizational agility. This is perhaps the greatest value of Lean Integration—the ability of the business to change rapidly without compromising on IT risk or quality, in other words, transforming the organization from one on the edge of chaos into an agile data-driven enterprise.

The Case for Lean Integration

The edge of chaos discussion makes the case for Lean Integration from a practitioner’s perspective, that is, that technology alone cannot solve the problem of complexity and that other disciplines are required. But that is more of an intellectual response to the challenge and still leaves the five questions we posed in the Introduction unanswered. Let’s address them now.

“Why Lean?” and “So What?”

In financial terms, the value of Lean comes from two sources: economies of scale and reduction in variation. Development of data and process integration points is a manufacturing process. We know from years of research in manufacturing that every time you double volume, costs drop by 15 to 25 percent.3 There is a point of diminishing returns since it becomes harder and harder to double volume, but it doesn’t take too many doublings to realize an order-of-magnitude reduction in cost. Second, we also know that manufacturing production costs increase from 25 to 35 percent each time variation doubles. The degree of integration variation today in many organizations is staggering in terms of both the variety of tools that are used and the variety of standards that are applied to their implementation. That is why most organizations have a hairball—thousands of integrations that are “works of art.”

3. George Stalk, “Time—The Next Source of Competitive Advantage,” Harvard Business Review, no. 4 (July–August 1988).

Some studies by various analyst firms have pegged the cost of integration at 50 to 70 percent of the IT budget. This is huge! Lean Integration achieves both economies of scale and reduction in variation to reduce integration costs by 25 percent or more. This book explores some specific case studies that we hope will convince you that not only are these cost savings real, but you can realize them in your organization as well.

“As a Business Executive, What Problems Will It Help Me Solve?”

The answer is different for various stakeholders. For IT professionals, the biggest reason is to do more with less. Budgets are constantly being cut while expectations of what IT can deliver are rising; Lean is a great way to respond because it embodies continuous improvement principles so that you can keep cutting your costs every year. By doing so, you get to keep your job and not be outsourced or displaced by a third party.

For a line-of-business owner, the big problems Lean addresses are time to market and top-line revenue growth by acquiring and keeping customers. A Lean organization can deliver solutions faster (just in time) because of automated processes and mass customization methods that are supported by the technology of an Integration Factory. And an integrated environment drives revenue growth through more effective use of holistic information, better management decisions, and improved customer experiences.

For an enterprise owner, the biggest reasons for a Lean Integration strategy include alignment, governance, regulatory compliance, and risk reduction. All of these are powerful incentives, but alignment across functions and business units may be the strongest contributor to sustained competitive advantage. By simply stopping the disagreement across teams, organizations can solve problems faster than the competition.

In summary, Lean Integration helps to reduce costs, shorten time to market, increase revenue, strengthen governance, and provide a sustainable competitive advantage. If this sounds too good to be true, we ask you to reserve judgment until you finish reading all the case studies and detailed “how-to” practices. One word of caution about the case studies: They convey how example organizations solved their problems in their context. The same practices may not apply to your organization in exactly the same way, but the thinking that went into them and the patterns may well do so.

“As an IT Leader or Line-of-Business Owner, Why Am I Going to Make a Considerable Investment in Lean Integration?”

Get results faster—and be able to sustain them in operation. Lean is about lead-time reduction, quality improvements, and cost reduction. Lean delivers results faster because it focuses heavily on techniques that deliver only what the customer needs (no “gold-plating”): process automation and mass customization. In terms of ongoing operations, Lean is a data-driven, fact-based methodology that relies heavily on metrics to ensure that quality and performance remain at a high level.

“How Is This Different from Other Methods, Approaches, and Frameworks?”

Two words: sustainable and holistic. Other integration approaches either tackle only a part of the problem or tackle the problem only for the short term at a point in time. The predominant integration strategy, even today, is customized hand-coded solutions on a project-by-project basis without a master plan. The result is many “works of art” in production that are expensive to maintain, require a long time to change, and are brittle in operation.

Note that Chapter 12, Integration Methodology, includes a section that explicitly compares agile and Lean methodologies.

“Why Am I as an IT Professional Going to Embrace and Sell Lean Integration Internally?”

Because it will advance your career. Time and time again we have seen successful integration teams grow from a handful of staff to 100 or more, not because of a power grab, but because of scope increases at the direction of senior management. Successful team members become managers, and managers become directors or move into other functions in the enterprise in order to address other cross-functional business needs. In short, Lean Integration is about effective execution, which is a highly valued business skill.

What Is Integration?

This seems like a simple question, but what exactly is integration? Here are a couple of examples of how others have answered this question:

• “The extent to which various information systems are formally linked for sharing of consistent information within an enterprise”4

4. G. Bhatt, “Enterprise Information Systems Integration and Business Process Improvement Initiative: An Empirical Study,” Proceedings of the First Conference of the Association for Information Systems (AIS), 1995.

• “Seamless integration of all information flowing through a company”5

5. T. H. Davenport, “Putting the Enterprise into the Enterprise System,” Harvard Business Review 16, no. 4 (July–August 1998), pp. 121–31.

A careful review of these and other definitions reveals a number of common themes that describe the essence of integration:

• Formally linked: Communication between systems is standardized.

• Seamless: Complexities are invisible to end users.

• Coordinated manner: Communication is disciplined.

• Synergy: Value is added to the enterprise.

• Single transactions that spawn multiple updates: There is master management of data.

• Fewer number of systems: The cost of ownership is lower.

• Non-duplicated data: The focus is on eliminating redundancy and reducing costs of management.

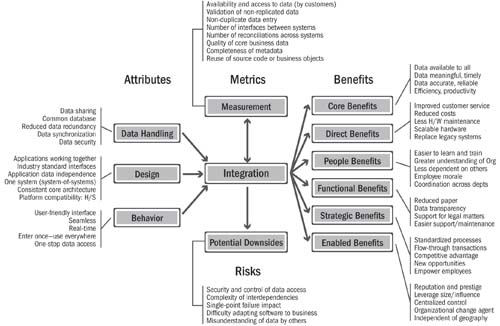

The most comprehensive definition of integration we have come across is in Lester Singletary’s doctoral dissertation.6 It provides a rich definition by examining the domain of integration from four perspectives: (1) what integration is in terms of its attributes or operational characteristics, (2) the benefits or resultant outcomes of effective integration efforts, (3) the risks or challenges that arise from integrations, and (4) the metrics that provide a measure of objectivity concerning the integrated environment. Figure 1.1 has been adapted from Singletary’s paper and serves as a foundation for our view of integration in this book.

6. Lester A. Singletary, “Empirical Study of Attributed and Perceived Benefits of Applications Integration for Enterprise Systems” (PhD dissertation, Louisiana State University, 2003).

Figure 1.1 Definition of integration

To put all this together, our definition of integration, therefore, is as follows:

Integration: An infrastructure for enabling efficient data sharing across incompatible applications that evolve independently in a coordinated manner to serve the needs of the enterprise and its stakeholders.

• Infrastructure: a combination of people, process, policy, and technology elements that work together (e.g., highway transportation infrastructure)

• Efficient data sharing: accessing data and functions from disparate systems without appreciable delay to create a combined and consistent view of core information for use across the organization to improve business decisions and operations

• Incompatible applications: systems that are based on different architectures, technology platforms, or data models

• Evolve independently: management decisions to change applications (or parts of an application) are made by different organizational groups or external suppliers on independent timelines that are not controlled by a master schedule

• Enterprise: the organization unit that is the focus of the integration effort; it could be a department, division, an entire company, or part of a supply chain

• Stakeholders: the customers of the enterprise, its owners, and its employees, including management, end users, and IT professionals

Integration Maturity Levels

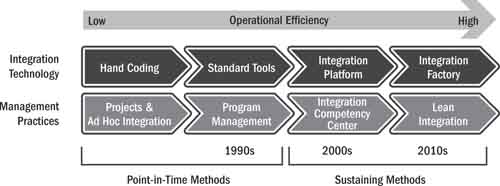

Another way to look at integration is to examine how integration technologies and management practices have evolved and matured over the past 50 years. Figure 1.2 summarizes four stages of evolution that have contributed to increasingly higher levels of operational efficiency. Hand coding was the only technology available until around 1990 and is still a common practice today, but it is gradually being replaced by modern methods. The movement to standard tools, more commonly known as middleware, began in the 1990s, followed by industry consolidation of tool vendors during the first decade of the 2000s, resulting in more “suites” of tools that provide the foundation for an enterprise integration platform.

Figure 1.2 Evolution of integration technology and management practices

As we look to the future, we see the emergence of the Integration Factory as the next wave of integration technology in combination with formal management disciplines. This wave stems from the realization that of the thousands of integration points that are created in an enterprise, the vast majority are incredibly similar to each other in terms of their structure and processing approach. In effect, most integration logic falls into one of a couple of dozen different “patterns” or “templates,” where the exact data being moved and transformed may be different, but the general flow and error-handling approach are the same. An Integration Factory adds a high degree of automation to the process of building and sustaining integration points. We believe the Integration Factory, described in detail in Chapter 3, will be the dominant new “wave” of middleware for the next decade (2010s).

Management practices have also evolved from ad hoc or point-in-time projects, to broad-based programs (projects of projects), to Integration Competency Centers (ICCs), and now to Lean Integration. A major paradigm shift began early in the current century around the view of integration as a sustaining practice. The first wave of sustainable management practices is encapsulated by the ICC. It focused primarily on standardizing projects, tools, processes, and technology across the enterprise and addressing organizational issues related to shared services and staff competencies. The second wave of sustainable practices is the subject of this book: the application of Lean principles and techniques to eliminate waste, optimize the entire value chain, and continuously improve. The management practice that optimizes the benefits of the Integration Factory is Lean Integration. The combination of factory technologies and Lean practices results in significant and sustainable business benefits.

The timeline shown on the bottom of Figure 1.2 represents the period when the technology and management practices achieved broad-based acceptance. We didn’t put a date on the first evolutionary state since it has been with us since the beginning of the computer software era. The earlier stages of evolution don’t die off with the introduction of a new level of maturity. In fact, there are times when hand coding for ad hoc integration needs still makes sense today. That said, each stage of evolution borrows lessons from prior stages to improve its efficacy. We predict that Lean practices, in combination with past experiences in project, program, and ICC practices, will become the dominant leading practice around the globe during the 2010s.

In Part III of this book we refer to these four stages of evolutionary maturity when discussing the eight integration competency areas. The shorthand labels we use are as follows:

1. Project: disciplines that optimize integration solutions around time and scope boundaries related to a single initiative

2. Program: disciplines that optimize integration of specific cross-functional business collaborations, usually through a related collection of projects

3. Sustaining: disciplines that optimize information access and controls at the enterprise level and view integration as an ongoing activity independent of projects

4. Lean: disciplines that optimize the entire information delivery value chain through continuous improvement driven by all participants in the process

We think of this last level of maturity as self-sustaining once it becomes broadly entrenched in the organization.

We don’t spend much time in this book discussing project or program methods since these are mature practices for which a large body of knowledge is available. Our focus is primarily on sustaining practices and how Lean thinking can be applied to achieve the highest levels of efficiency, performance, and effectiveness.

Economies of Scale (the Integration Market)

As stated earlier, the benefits of Lean are economies of scale and reduction in variation. As a general rule, doubling volume reduces costs by 15 to 25 percent, and doubling variation increases costs by 25 to 35 percent. The ideal low-cost model, therefore, is maximum standardization and maximum volume. But how exactly is this accomplished in a Lean Integration context?

A core concept is to view the collection of information exchanges between business applications in an enterprise as a “market” rather than as a bunch of private point-to-point relationships. The predominant integration approach over the past 20 years has been point-to-point integration. In other words, if two business systems need to exchange information, the owners and subject matter experts (SMEs) of the two systems would get together and agree on what information needed to be exchanged, the definition and meaning of the data, the business rules associated with any transformations or filters, the interface specifications, and the transport protocol. If anything needed to change once it was in operation, they would meet again and repeat the same process.

For a small number of systems and a small number of information exchanges, this process is adequate and manageable. The problem with a hand-coded or manual method is that it doesn’t scale, just as manual methods for other processes don’t scale well. Certainly if a second integration point is added to the same two systems, and the same two SMEs work together and use the same protocols, documentation conventions, and so on, the time and cost to build and sustain the integrations will indeed follow the economy of scale cost curve. But in a large enterprise with hundreds or thousands of applications, if each exchange is viewed as strictly an agreement between the immediate two parties, diseconomies begin to creep into the equation from several perspectives.

Imagine trying to follow a flow of financial information from a retail point-of-sale application, to the sales management system (which reconciles sales transactions with refunds, returns, exchanges, and other adjustments), to the inventory management system, to the general ledger system, to the financial reporting system. In a simple scenario, this involves four information exchanges among five systems. If each system uses different development languages, protocols, documentation conventions, interface specifications, and monitoring tools and was developed by different individuals, not only will we not receive the benefits from quadrupling volume from one integration to four, but we will in fact increase costs.

This example reflects the two largest factors that drive diseconomies: the cost of communication between teams and duplication of effort. Additional factors can drive further diseconomies, such as the following:

• Top-heavy organizations: As organizations get larger and add more layers of management, more and more effort needs to be expended on integrated solutions that require collaboration and agreement across teams that each play a narrow functional role.

• Office politics: Disagreements across teams are a result of different motivations and agendas, usually a result of conflicting goals and metrics but also sometimes caused by the “not invented here” syndrome.

• Isolation of decision makers from the results of their decisions: Senior managers may need to make decisions, such as how much of a budget to allocate to a given group, without a clear picture of what the group does and what value it brings to the organization.

• Slow response time: Delays are caused by multiple handoffs between teams or by queuing requests for information or support from other groups.

• Inertia: People are unwilling to change or are opposed to standards.

• Cannibalization: Limited resources (such as SMEs in specific business domains) are consumed for project B, slowing down progress on project A.

The degree of integration variation in many organizations is staggering in terms of both the variety of technology that is used and the variety of standards that are applied to their implementation. That is why most organizations have a hairball—hundreds or thousands of integrations that are “works of art.”

The alternative is to view the need for information exchanges across applications as a market economy, and to serve the market with an efficient shared-services delivery model in order to gain economies of scale. For example, multiple groups within an organization may perform similar activities but do so with varying degrees of efficiency and consistency. Centralizing the activities makes it much easier to standardize and streamline the work, thereby reducing the cost per unit of work while improving the quality and consistency.

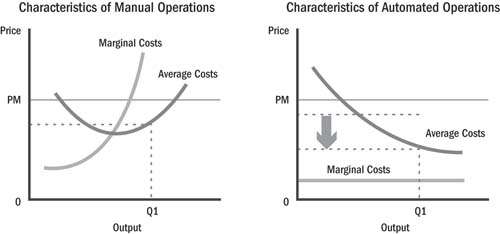

The two graphs in Figure 1.3 are borrowed from the field of economics and show the relationships between costs and volumes. These graphs reflect the well-understood laws of diminishing returns and economies of scale. The chart on the left reflects a manual or low-tech operation, such as when information exchanges are developed using custom hand-coded integration solutions. In this scenario, there are few (if any) capital costs since existing enterprise tools such as COBOL, Java, or SQL are used to build the integration. The overall average cost per integration initially falls as the individuals doing the work gain experience and are able to share some of their experience and knowledge, but then at some point it starts to increase as diseconomies emerge. In terms of the marginal costs (i.e., the incremental cost for each additional integration), initially the curve is somewhat flat since the first integration developer can develop a second or third integration with a similar effort. The average cost also falls initially since the fixed costs of the developer (hiring costs, office space, desktop PC, etc.) are amortized over more than one integration. As the volume of integrations increases, however, the marginal costs increase on an exponential basis, and the average costs begin to increase as more and more diseconomies emerge from the increasing complexity and number of unique integration points.

Figure 1.3 Diminishing returns and economies of scale

The chart on the right of the figure shows the cost curve as a result of a capital investment in tools and infrastructure (such as an Integration Factory) to largely automate and standardize the development effort. Note that in this scenario, the marginal costs are small and constant. For example, it might cost Microsoft $5 billion to develop a new version of Windows, but once developed, it costs just pennies to make another electronic copy. The marginal cost per copy of Windows is essentially the same whether 1 copy or 1,000 copies are made, but the average cost drops significantly and continuously in this scenario as volume increases and as the up-front fixed costs are amortized over more and more units.

The key challenge for organizations is to determine at what level of integration complexity do diminishing returns begin to emerge from manual hand-coded solutions, and how much capital investment is warranted to achieve the time and cost advantages of a high-volume Integration Factory. The answer to this will become clearer in Parts II and III, where we discuss the Lean principles related to continuous improvement, mass customization, and process automation, and the financial management competency area.

Getting Started: Incremental Integration without “Boiling the Ocean”

Parts II and III of the book provide detailed and specific advice on how to implement a sustainable Lean Integration practice, but before you dig into the details, it is important to understand the approach options and related prerequisites.

There are two fundamental implementation styles for Lean Integration: top-down and bottom-up. The top-down style starts with an explicit strategy with clearly defined (and measurable) outcomes and is led by top-level executives. The bottom-up style, which is sometimes referred to as a “grassroots” movement, is primarily driven by front-line staff or managers with leadership qualities. The top-down approach generally delivers results more quickly but may be more disruptive. You can think of these styles as revolutionary versus evolutionary. Both are viable.

While Lean Integration is relevant to all large organizations that use information to run their business, there are several prerequisites for a successful Lean journey. The following five questions provide a checklist to see if Lean Integration is appropriate to your organization and which style may be most suitable:

1. Do you have senior executive support for improving how integration problems are solved for the business?

Support from a senior executive in the organization is necessary for getting change started and critical for sustaining continuous improvement initiatives. Ideally the support should come from more than one executive, at a senior level such as the CXO, and it should be “active” support. You want the senior executives to be leading the effort by example, pulling the desired behaviors and patterns of thought from the rest of the organization.

It might be sufficient if the support is from only one executive, and if that person is one level down from C-level, but it gets harder and harder to drive the investments and necessary changes as you water down the top-level support. The level of executive support should be as big as the opportunity. Even with a bottom-up implementation style, you need some level of executive support or awareness. At some point, if you don’t have the support, you are simply not ready to formally tackle a Lean Integration strategy. Instead, just keep doing your assigned job and continue lobbying for top-level support.

2. Do you have a committed practice leader?

The second prerequisite is a committed practice leader. By “committed” we don’t mean that the leader needs to be an expert in all the principles and competencies on day one, but the person does need to have the capability to become an expert and should be determined to do so through sustained personal effort. Furthermore, it is ideal if this individual is somewhat entrepreneurial, has a thick skin, is customer-oriented, and has the characteristics of a change agent (see Chapter 6 on team empowerment for more details).

If you don’t have top leadership support or a committed practice leader, there is little chance of success. This is not to suggest that a grassroots movement isn’t a viable way to get the ball rolling, but at some point the bottom-up movement needs to build support from the top in order to institutionalize the changes that will be necessary to sustain the shift from siloed operations to integrated value chains.

3. Is your “Lean director” an effective change agent?

Having a Lean director who is an effective change agent is slightly different from having one who is “committed.” The Lean champion for an organization may indeed have all the right motivations and intentions but simply have the wrong talents. For example, an integrator needs to be able to check his or her ego at the door when going into a meeting to facilitate a resolution between individuals, who have their own egos. Furthermore, a Lean perspective requires one to think outside the box—in fact, to not even see a box and to think of his or her responsibilities in the broadest possible terms. Refer to the section on Change Agent Leadership in Chapter 6 for a description of essential leadership capabilities.

4. Is your corporate culture receptive to cross-organizational collaboration and cooperation?

Many (maybe even most) organizations have entrenched views of independent functional groups, which is not a showstopper for a Lean program. But if the culture is one where independence is seen as the source of the organization’s success and creativity, and variation is a core element of its strategy, a Lean approach will likely be a futile effort since Lean requires cooperation and collaboration across functional lines. A corporate culture of autonomous functional groups with a strong emphasis on innovation and variation typically has problems implementing Lean thinking.

5. Can your organization take a longer-term view of the business?

A Lean strategy is a long-term strategy. This is not to say that a Lean program can’t deliver benefits quickly in the short term—it certainly can. But Lean is ultimately about long-term sustainable practices. Some decisions and investments that will be required need to be made with a long-term payback in mind. If the organization is strictly focused on surviving quarter by quarter and does little or no planning beyond the current fiscal year, a Lean program won’t achieve its potential.

If you are in an organizational environment where you answered no to one or more of these questions, and you feel compelled to implement a Lean program, you could try to start a grassroots movement and continue lobbying senior leadership until you find a strong champion. Or you could move to another organization. There are indeed some organizational contexts in which starting a Lean program is the equivalent of banging your head against the wall. We hope this checklist will help you to avoid unnecessary headaches.

Lean requires a holistic implementation strategy or vision, but it can be implemented in incremental steps. In fact, it is virtually impossible to implement it all at once, unless for some reason the CEO decides to assign an entire team with a big budget to fast-track the implementation. The idea is to make Lean Integration a long-term sustainable process. When we say “long-term” we are talking about 10 to 20 years, not just the next few years. When you take a long-term view, your approach changes. It certainly is necessary to have a long-term vision and plan, but it is absolutely acceptable, and in many respects necessary, to implement it incrementally in order to enable organizational learning. In the same way, an ICC can start with a small team and a narrow scope and grow it over time to a broad-based Lean Integration practice through excellent execution and positive business results.