Chapter 2

Introducing Business Transformation

In This Chapter

![]() Establishing the organisation’s True North and working out how to get there

Establishing the organisation’s True North and working out how to get there

![]() Doing the right things right

Doing the right things right

![]() Recognising what can go wrong along the way

Recognising what can go wrong along the way

![]() Communicating about the journey to your stakeholders

Communicating about the journey to your stakeholders

In this chapter we look at the importance of having a clearly communicated vision of where you want to be; one that engages the organisation and secures people’s buy-in to the planned journey. To do this you need to establish and appropriately communicate your ‘True North’ and determine a route or road map to get you there.

The thing about maps, however, is that they’re only really of use if you know where you are to begin with. Taking stock of the organisation’s current performance and its capability to undertake the transformation journey is an essential early step. We introduce the DRIVE model as the overarching framework to successfully achieve the transformation, but throughout the chapter we highlight the importance of the soft stuff.

The transformation journey is unlikely to be easy, so wherever possible do seek to make things as simple as possible, but not too simple.

Determining Where You Are Now and Where You Need to Be

In many ways, the essence of this section is pretty much in line with a conversation between Alice and the Cheshire Cat in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll:

‘Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.

‘I don’t much care where –’ said Alice.

‘Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,’ said the Cat.

‘– so long as I get somewhere,’ Alice added as an explanation.

‘Oh, you’re sure to do that,’ said the Cat, ‘if you only walk long enough.’

Before setting off on a ‘transformation journey’ you need to know where you are currently as an organisation. How effective are your products, services and supporting processes? And what do your customers and employees feel about things?

You may have a good idea of where you would like to be, but understanding the starting point and your current capabilities for setting off on a journey are vital. The approach we describe throughout this book provides the map, but a map is of little use without knowing where you’re starting out from or, of course, where you’re going!

Where are you now?

Where indeed? Before setting off on your transformation journey, answering that question is essential. And, as indicated above, you’ll need to answer a number of other important questions too. In particular, you should ask questions that help you consider how good your organisation has been in the past and recently at executing its business strategy. Good questions lead to good data, which lead to good information, and finally to good decisions that will help you on your journey.

See if you can answer the following questions – and the answers really will count:

- Customers: How do your customers feel? What do perception surveys reveal? Is market share increasing or are you losing customers?

- Employees: How do your staff feel? Are they frustrated because they don’t seem able to do things easily or feel that their roles are unclear? Do they feel empowered and involved in how the business is run? Maybe you’re spending too much time dealing with unhappy customers and their complaints.

- Processes: How stable are the processes operating within your organisation? Do clearly defined ways of doing things exist – the one best way – or are lots of people doing their own thing and muddling through?

- The organisation: Depending on what you want the transformation to achieve, do you have a clear idea about whether the organisation has the right skills and expertise in place to be successful?

Obviously, you could ask many more questions. What’s important, however, is asking the right questions. A particularly vital issue is finding out which members of the senior management team are likely to be supportive of the changes you have in mind. The ‘Checking that everyone’s on board’ section, later in this chapter, covers stakeholder buy-in.

One of the key concepts of Lean Six Sigma is managing by fact. Managing by fact requires good data, and that data needs to be presented in an appropriate way. So, what does the data show? And is it the right data? Good data is different from the right data. Good data is representative, recorded using the appropriate measurement scale, timely, precise, and unbiased. The right data comes from measuring the right things.

But, as Albert Einstein once said,

‘Not everything that can be counted counts; not everything that counts can be counted.’

Our experience with organisations across the globe has shown us that many have data coming out of their ears – unfortunately, not necessarily the right data, and not always good. Often such data is merely that which can be obtained, rather than data that helps with understanding performance and taking appropriate decisions and actions. This requires that the user translates data into meaningful information, and then has a process for making decisions based on this information. Linking data with decisions is a principle for transformation efforts based on Lean Six Sigma.

Where are you going?

Unlike Alice, you need to be clear about where you’re going – that is, your aim. Whether this means launching the organisation in new markets or enhancing performance in a bid to stop loss of customers, you need to articulate a clear objective and purpose.

Present your vision for the transformation as simply as possible: don’t hide it within a voluminous management report. Use language that everyone can understand and present any data in a straightforward manner.

You may find techniques such as the 15-word flipchart and the elevator speech helpful in putting together a simple and easily understood vision. The 15-word technique involves people using sticky notes to draft their own vision statements in a maximum of 15 words. When these are put up on the flipchart, the team can highlight key phrases or words that need to be encompassed within the final statement, which can be as many words as you need.

This technique can also be helpful in drafting an elevator speech, which provides the basis for a brief ‘sales pitch’ of what you want to achieve. See Chapter 4 for more techniques to help with presenting your transformation vision.

How will you get there?

Transformation is likely to include more than Lean Six Sigma techniques and process improvements. Thus, although this book is about transformation using Lean Six Sigma, other approaches are also used, such as a focus on talent management and people development.

Successful transformation is achieved by following a maturity road map that sets out the stages of the journey ahead. Supported by Lean Six Sigma, the transformation process involves effective strategy deployment and needs the buy-in of people at all levels of the organisation. The importance of the people involved and their buy-in (often referred to as the ‘soft stuff’) cannot be overstated, but the route itself is unlikely to be soft – changing thinking and behaviours usually results in some bumpy ups and downs along the way. We look at the importance of the soft stuff in the ‘Dealing with the soft stuff’ section, later in this chapter, and in more detail still in Chapter 11.

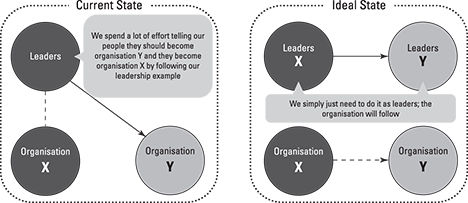

Creating the right environment is a must. Essentially, the leaders must ‘walk the talk’. As well as encouraging the application of Lean Six Sigma thinking, principles, tools and techniques, the leaders have to be seen to be using them themselves. Figure 2-1 highlights that lip service – ‘Follow me, I’m right behind you’ – simply doesn’t work.

Figure 2-1: Walking the talk.

Leaders also need to provide the right training, coaching and support for people to ensure that the infrastructure necessary for success is in place. It might also be appropriate to review or introduce an appropriate recognition system that demonstrates appreciation for the efforts and achievements of people. A management sponsor, ideally the chief executive, must also be appointed, as well as someone to manage and co-ordinate the overall programme of activities.

You need to avoid duplication of effort by making certain that different improvement teams are not trying to improve the same thing. A transformation board or steering group that holds regular, focused meetings can help make sure that improvement activity in one area does not adversely impact on another. The transformation board needs to receive information from tollgate reviews (or other project reports) to do this. For large organisations, the entire steering group cannot be expected to attend every project tollgate review and an appropriate approach will need to be agreed. You’ll probably want to create a programme management office to help co-ordinate things, something we refer to in Chapter 6. And if you want to find out more about tollgate reviews, check out Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley).

Without this co-ordination and an understanding of the processes and how they flow across the organisation, sub-optimisation can happen all too easily, and the journey can become confused by wrong turnings and cul-de-sacs.

Going for a drive

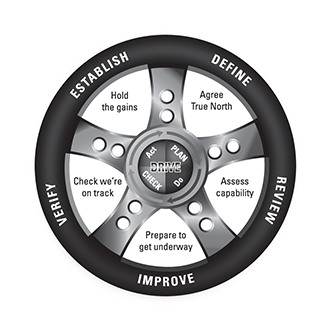

Successful transformation needs drive and energy; it won’t happen without it. And transformation really is a journey. The DRIVE model (Define, Review, Improve, Verify and Establish), illustrated in Figure 2-2, provides the framework to help you travel from where you are to where you want to be.

Figure 2-2: Steering in the right direction with the DRIVE model.

In the Define phase, you’ve recognised the need to transform and have agreed where you want the organisation to be – its ‘True North’. The Review phase provides a reality check that assesses the organisation’s capability in terms of achieving the change needed. The Improve phase has three elements: preparing for the journey, shaping and scoping what needs to be done, and implementing the agreed actions and projects.

In the Verify phase you’re monitoring progress and performance against plan to ensure that you’re on track. And in Establish, you ensure the gains made are held as you seek to embed the new ways of working into the organisation’s DNA. We look at the DRIVE model in more detail in Chapter 3, and many of the subsequent chapters refer to the various elements of the model as the journey to True North unfolds.

Understanding the Key Principles of Business Transformation

The overall goal of transformation is to get the whole organisation moving in the same direction and doing the right things to increase capability and achieve strategic intent. The strategy needs to be broken down into actionable steps, but in a way that ensures the scope of the tactical actions are properly agreed and clearly link to the strategic thinking.

Identifying True North

Finding True North is essential for accurate navigation, hence the metaphor we use throughout this book. In life’s journey we’re often uncertain about where we stand, where we’re going and what path is right for us. Knowing our True North enables us to follow the right path.

The organisation’s True North is where the organisation wants to be. On maps published by the United States Geological Survey, True North is marked with a line terminating in a five-pointed star. And it may well be that ‘five-star’ performance is your organisation’s goal. Either way, the strategic and potentially philosophic aims and objectives of the planned transformation need to be agreed and shared in a way that everyone understands. And everyone should be able to see how the objectives of the various transformation plan actions and projects move the organisation closer to its True North destination.

Following a clear strategic direction

The organisation needs to be aligned and to share a common focus and purpose.

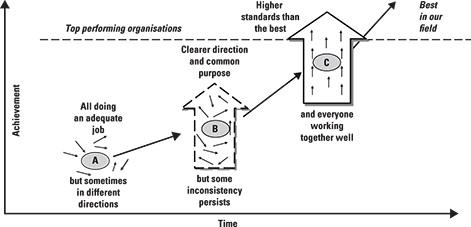

Olympic rowers know only too well that unless the team is rowing in time and in the same direction they’ll never achieve gold. Organisations are no different, though often a lack of common purpose is evident and, while everyone is working hard, they’re not all focused on working on the right things. Getting everyone working well together in the quest for True North won’t happen overnight. It will take time and effort and it demands clear direction from the top.

Planning the route

The organisation’s strategy needs to be formulated and effectively deployed. Different approaches to strategy or policy deployment exist, including the application of the balanced scorecard (see Chapter 5), and what the Japanese refer to as Hoshin Kanri. The scorecard approach tends to look at the deployment of holistic strategy, whereas Hoshin Kanri is usually more tightly focused on specific strategic objectives. In the US, Hoshin Kanri tends to be focused on policy deployment.

Hoshin Kanri has several meanings, including ‘shiny metal’ or ‘a compass’. The latter fits well with another interpretation: ‘ship in a storm going in the right direction’. The image most often depicted in US literature on Hoshin Kanri is that of a ship’s compass distributed to many ships, properly calibrated such that all ships through independent action arrive at the same destination, individually or as a group, as the requirements of the voyage may require. And, of course, this is what you’re trying to do with all the different teams and departments in your organisation as you move towards your True North. Hoshin Kanri is a method devised to capture and cement strategic goals as well as flashes of insight about the future, and develop the means to make them a reality. Hoshin Kanri makes it possible to get away from the status quo and introduce a major performance improvement, the transformation, by analysing current problems, determining the actions needed and deploying appropriate strategies. It cascades down from top management and through the management hierarchy. Each level of management is, in turn, involved with the level above it to make sure that its proposed strategy, plans and projects fit together appropriately and avoid any disconnects or duplications.

Actioning the deployment in this way ensures that everyone in the organisation is made aware of the overall vision and targets, and the way that these are translated into specific requirements for their own behaviour and activities. In the most successful organisations, all employees clearly understand how their roles and objectives link to the key goals.

Using Hoshin Kanri, top management vision is translated into a set of consistent, understandable and attainable actions to be applied at all levels and functions. This approach turns a vision into reality; it sets out the route to success and begins the process of lining up the arrows referred to in Figure 2-3. The route will almost certainly need a series of DMAIC and DMADV projects that will become the vehicles for moving the organisation forward (see Chapter 1).

Figure 2-3: Lining up the arrows.

Hoshin Kanri was developed by Yoji Akao and uses Walter Shewhart’s Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) model (see Figure 1-1 in Chapter 1) to create goals, agree measurable milestones and link daily control activities to strategy.

The strategy or policy deployment approach provides an opportunity to continually improve performance by disseminating and deploying the vision, direction, targets and plans of the organisation to people at all job levels, ensuring their involvement and understanding. In organisations using Hoshin Kanri everybody is aware of management’s vision for the transformation. Departments don’t compete against each other, projects run to successful conclusions, and business is seen as a set of co-ordinated processes.

Keeping it simple

Organisations should always look to find ways of keeping things simple. Unfortunately, simplicity looks easy – but isn’t. In fact, it’s much easier to complicate than to simplify. Simple ideas enter the brain quicker and stay longer. In the words of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, simplicity is thus ‘a painful necessity’.

Keeping things simple removes irrelevance and waste. With simplicity of thought it may be possible to change the world, but starting with your own organisation and its processes is a good first step!

Winston Churchill was a great believer in simplicity. He liked to quote a letter French mathematician and writer Blaise Pascal wrote to a friend. It began: ‘I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.’ He knew that achieving simplicity is difficult, but also necessary. Churchill stressed this theme again when he said that to deliver a two-hour speech he needed 10 minutes of preparation, but to deliver a 10-minute speech he needed two hours of preparation.

The strategies should be clear and simple. Less is more, so present them on no more than a page. And keep that to a side of A4, too!

Keeping on track

On most journeys you usually encounter tempting diversions en route. You have to stay focused and ensure you’re making progress and meeting targets. Developing a plan is usually pretty straightforward – it’s achieving it that’s a challenge. This applies both to the individual actions and improvement projects, as well as, of course, to the transformation plan overall.

You need to keep checking progress, which means having good data and holding regular tracking meetings. Consider again the PDCA cycle. You’ve developed your Plan and you’re now doing the things that have been agreed. The Check phase involves looking to see whether what you thought would happen is happening. If it isn’t, you need to Act in some way. It might be that your plan and theories need some adjustment.

The individual Lean Six Sigma projects, whether using DMAIC or DMADV, will have tollgate reviews built in to the process. A tollgate review checks that you’ve completed the current phase properly and reviews the team’s various outputs from it. These reviews also identify issues relating to risk. New risks may surface; feared risks may be downgraded or eliminated. Risk assessment is important in both project reviews and transformation reviews. For more on tollgate reviews, see Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley).

The project team and the management sponsor or champion of the improvement activity should conduct the tollgate reviews. In effect, you’re passing through a tollgate. Let’s take a look at DMAIC by way of example. Chapter 1 provides an overview of the Define, Measure, Analyse, Improve and Control phases. Before moving from one phase to another, you need to step back, assess progress and ask some key questions, such as:

- How are things going?

- Are we on course?

- What have we learnt?

- What’s gone well, and why?

- What conclusions can be drawn?

You need to make sure the project will deliver your planned benefits, so three benefit reviews’ are built into the DMAIC framework. Before the project began, you’ve probably best guessed a business case that justifies starting the work. By the end of the Analyse phase, you’ll know what’s happening and why, and should be able to determine the benefits to both the organisation and your customers. These could be financial savings for the organisation, or enhanced service delivery to the customers, for example.

In the Improve phase, you select the most appropriate solution. Once you’ve carried out a pilot you should be able to confirm the benefits both for the organisation and the customer. The final review at the end of the project and following the implementation of the solution enables you to confirm the actual costs and benefits and whether any unexpected debits or credits have emerged. You should also know the answers to these questions:

- Do your customers recognise that an improvement has occurred? How do you know?

- Can lessons, ideas or best practices from this project be applied elsewhere in the organisation?

The DMAIC and DMADV projects are component parts of achieving the transformation. Taking time for these reviews and tollgates not only keeps you on track but also forms an important element in developing a culture that manages by fact. So, take the opportunity to review progress – it will help ensure your projects are successful and the desired benefits are actually delivered.

Doing the right things

You need to ensure that the right improvement projects are selected and are appropriately focused and scoped. They should clearly link to the organisation’s strategic aims and objectives so that everyone involved can see how successful implementation will help improve overall performance and move the organisation towards its desired state.

Understanding the top-level processes or value streams of the organisation and being able to pinpoint the areas for improvement activity should lead to the appropriate identification of improvement projects.

This process is further facilitated where you’re able to genuinely manage by fact, using accurate data that measures the right things.

Doing things right

At a literal level, you’re looking to avoid errors and defects by doing the work right. But the focus here is on using the right methods and approaches to do so. At a process level, ‘one best way’ of doing the work should exist. With process improvement projects, for example, it’s important to distinguish between those problems that can be tackled as a ‘Rapid Improvement’ or ‘Kaizen Events’ and those that need to be approached in a more formal way using DMAIC over a period of perhaps three or four months.

Kaizen (pronounced Kai Zen) means change for the better. It’s often associated with short, rapid, incremental improvement and forms a natural part of an organisation’s approach to continuous improvement (see Chapter 12). These events usually have a narrowly scoped focus and address and solve a process problem in a series of workshops over a few days.

The DMAIC method will not be appropriate for some projects, such as purchasing a new computer system or developing a new factory site, and these need to be project managed, possibly using the PRINCE methodology. PRINCE (PRojects IN Controlled Environments) is a recognised method for effective project management. It is used extensively in the public and private sectors, both in the UK and internationally. The Project Management Institute (PMI) in Philadelphia provides another internationally recognised method as an option.

Given the aim of transforming the organisation, it’s highly likely a need will exist for design projects using the DMADV method.

Dealing with the soft stuff

The ‘How will you get there?’ section earlier in this chapter looked at the importance of creating the right environment for transformation. An appreciation of the ‘soft stuff’ is crucial here. Successful transformation isn’t simply about setting a series of projects in motion.

So what exactly do we mean by the ‘soft stuff’? In simple terms, it’s about how well you work with the people involved in the transformation process and the stakeholders who are affected by it. You may well have developed an ideal solution or approach, but its effectiveness will depend on its acceptance.

The effectiveness of an improvement project or, indeed, the deployment of the strategy overall hinges on two broad factors: quality and acceptance. George Eckes, CEO of a Colorado-based consulting group and a former psychologist, came up with a formula to help express the importance of the ‘soft stuff’: E = Q × A.

E = Effectiveness: E represents the effectiveness of the implementation, which depends on the quality of the solution and its level of acceptance.

Q = Quality of the solution: An ideal solution may have been identified, but its effectiveness is dependent on its acceptance.

A = Acceptance of the solution: The level of acceptance of the solution is key because it affects the overall success of the implementation throughout the organisation.

Clearly, communication will be vital throughout. You need to develop a communication plan as part of your overall deployment plan to ensure you get the right messages to the right people at the right time and in an appropriate medium. Try to think about the different audiences both as teams and individuals.

Looking Out for the Pitfalls

Transforming an organisation is unlikely to be without its challenges. Unfortunately, it’s all too easy for things to go wrong, not only when you’re en route but even before you’ve set off on the journey. Understanding who’s on your side and who isn’t is vital – you’ll probably encounter some people who say the right words but don’t walk the talk.

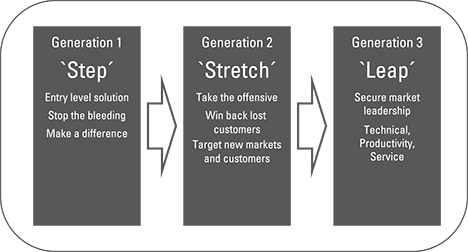

Because some people will be tempted to try to do things faster than is practicable, look to agree actions in bite-sized chunks. You may find a technique such as Multi-Generation-Planning (MGP) useful here.

The MGP technique provides the basis for a series of projects for your products, services and processes, perhaps over several years. It is based around the concept of a ‘step–stretch–leap’ strategy. It’s described in more detail in the ‘Taking on too much too soon’ section later in this chapter.

Checking that everyone’s on board

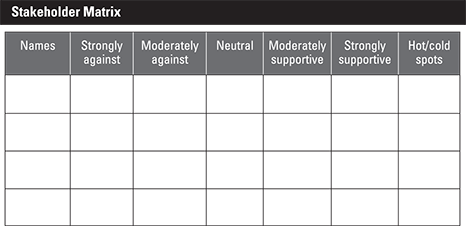

Not everyone will like the destination or the route. Hopefully, those people can be won round, but that might not be the case. Carrying out a stakeholder analysis – see Figure 2-4 – is an important step both before and after you announce the planned destination of your journey.

The stakeholder analysis will be based on your perceptions, of course, but you need to feel you have the right people on board for the journey ahead, especially when it comes to the senior management team.

Figure 2-4: Stakeholder analysis.

No matter what issue you’re addressing, some people will be very much for it, some completely against, some in-between, and some indifferent. And that’s pretty much life so don’t be surprised when you find this picture applying to your transformation objectives or to the changes emerging from the DMAIC and DMADV projects that your teams eventually develop. And if you can’t see that picture, then you better find out what the situation looks like, both on the surface and beneath it.

Stakeholder analysis helps you develop a detailed sense of who the key stakeholders are, how they currently feel about the change initiative, and the level of support they need to exhibit for the change initiative to have a good chance of success. It also helps determine ways to influence relationships and develop strategies that will be effective for each key stakeholder.

First, you need to identify the stakeholders.

Consider these questions:

- Who are the stakeholders?

- Where do they currently stand on the issues associated with the change initiative?

- Are they supportive?

- How supportive?

- Are they against?

- And how much against?

- Are they broadly neutral?

Given their status or influence on your project, where do you need these stakeholders to be? It may be both desirable and possible to move some stakeholders to a higher level of support. How will you do that? Can you identify their hot and cold buttons? How can you present the vision and its supporting projects in a more appealing and effective way for them? Sometimes it may be entirely appropriate for stakeholders to adopt a neutral position. And every now and then, it might be appropriate to scale down someone’s support.

Figure 2-4 provides a framework for your stakeholder analysis, enabling you to capture and present your perceptions. You begin by mapping your perceptions of each stakeholder’s current position. List each stakeholder along the left side of the chart and then consider where you feel each one is at the moment. In assessing each individual, examine both objective evidence and subjective opinion. A key stakeholder is anyone who controls or influences critical resources, who can block the change initiative by direct or indirect means, who must approve certain aspects of the change strategy, who shapes the thinking of other critical parties or who owns a key work process impacted by the change initiative.

Once you’ve identified whether each stakeholder is against, neutral or supportive, you need to decide where each stakeholder needs to be for the change initiative to be successful. Remember, some stakeholders may need only to be shifted to neutral to stop them being an active blocker.

The next step is to develop an effective strategy for influencing the stakeholders in order to increase, or at least maintain, their level of support. The hot and cold buttons come into play at this point. Sometimes it will be a simple matter of presenting information in the right way for a particular person. Some will prefer lots of detail; others will want only a high-level summary. Some will want facts and figures; others will prefer pictures.

Whatever the approach, you need to give careful thought to which person will have most impact on a particular stakeholder, the nature of the message that needs to be delivered, and how and when the influence process should begin.

In determining ways in which to move particular stakeholders, remember that help may be available from those who are supporters of the initiative. A strongly supportive key stakeholder might also be a thought leader for others on your list. Consider how you can enlist their support in shaping the thinking of other, less supportive, stakeholders.

Considering what can go wrong

Just about anything and everything can go wrong! But it can all go right, too. For some people, changing their thinking and behaviour may be too difficult. What’s more, attempting to action all the tasks needed may seem beyond you. You’re probably going to be faced with trying to keep the existing work running at the same time as taking on the planning, scheduling and actioning of a whole series of projects.

The soft stuff can be forgotten about, deliberately or otherwise, and you may well have some staff trying to block progress and derail the change process. You may face a whole host of other potential problems, including lack of the right skills and expertise, insufficient resources and poor communication. As with any project or programme, carrying out a risk analysis will help you to identify the potential problems and prevent at least some of them from occurring. You can also use a risk analysis to develop contingency plans for when something does go wrong.

In terms of things that can go wrong with processes, we recommend using Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA). FMEA looks to identify what might go wrong (the ‘failure modes’) and assess the impact if it does (‘the effect’). It also considers how often the failure mode is likely to occur, and how likely you are to detect the failure before its effect is realised.

For each of these, you assign a value, usually on a scale of 1 to 10, to reflect the risk. To determine priorities for action, you need to calculate an RPN – a risk priority number. This value is simply the result of multiplying your ratings for the severity of the risk, the frequency of occurrence and the likelihood of detection. And, of course, you need to find ways to reduce the RPN. FMEA is described in more detail in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley).

Taking on too much too soon

Taking on too much too soon is tempting but potentially hazardous. Change is best carried out in bite-size chunks. Anything else can overwhelm you. Resist the temptation to try to do everything in one go.

With a transformation programme, you know where you want to be but recognise that getting there will take some time and effort. And, of course, transformation is likely to be achieved in a series of projects rather than in one hit. The MGP provides the basis for a series of projects for your products, services and processes, perhaps over several years, based on the concept of a ‘step–stretch–leap’ strategy (as illustrated in Figure 2-5). Each ‘generation’ looks to focus on a different aspect of meeting market and customer requirements, with the longer-term aim of securing market leadership. Imagine that service delivery is the issue that needs to be dealt with; the typical three-part strategy would then be along these lines.

In the first generation of a product or service, and in the management and improvement of the supporting processes, you’re looking to take remedial action and close the gaps in order to prevent the defection of customers to competitors. Doing so may include identifying and closing gaps in the market itself. The second generation looks to build on the success of this first strategy by enhancing your processes further, and perhaps developing products and services that target new markets, the customers of competitors, or attempting to win back lost customers. Finally, in the third generation, you try to achieve market leadership through breakthroughs. These might be in technical expertise, productivity, exceptional service or possibly a combination of all three.

Figure 2-5: Step, stretch and leap towards transformation.

Developing an MGP helps you to present a vision of what you’re trying to achieve, but does so in a way that highlights the phases and rationale behind what you’re doing. And, of course, you can incorporate the feedback and learning from one generation into the future generations of the product or process. Doing so should help you manage risks and contain costs more effectively, and lead to a smoother and perhaps faster transition to the longer-term desired state.

Accentuating the positive with negative brainstorming

Negative brainstorming identifies what you don’t want to achieve. So, for example, you might ask a team, ‘How can we ensure our strategy deployment plan fails?’ or ‘How can we make certain the transformation journey never leaves the station?’ Potentially, the ideas will come thick and fast. Some may be a little silly, but that’s okay – a little fun will be no bad thing. Using sticky notes and creating an Affinity Diagram by sorting the notes into common themes and agreeing descriptive headers for each group is the best way to carry out a negative brainstorming exercise. Chapter 4 provides more detail about creating an Affinity Diagram.

Next comes the interesting part. You can do one of two things – or indeed both. First, you can identify those things that are already happening, which can be a salutary experience. Second, you can turn the statements, ideas and actions on the sticky notes into positives, providing a whole series of the things you need to do to achieve what you really want – a successful transformation and strategy deployment.

Negative brainstorming can work well in helping to identify some of the potential failure modes we referred to in the earlier section describing FMEA, ‘Considering what can go wrong’.

Creating the Vision

Engaging people and maintaining that engagement means you will need to have effective and ongoing communication in place. That communication must be appropriate for the different levels of staff within the organisation. Naturally, people will need to know what the organisation is seeking to do, just where True North is, and how the journey there is progressing.

Going backwards – more or less

Visions paint a picture that appeals to hearts and minds and helps answer the question, ‘Why change?’ In developing the desired state from the perspective of your customers, the business and your employees, you are effectively developing a future vision that you’re working towards.

A vision should provide a clear statement about the outcomes of the change effort, and in doing so, help identify at least some of the elements that need to be changed. A vision secures commitment and support by helping people understand what it is that has to be done – and why.

Depending on the aims of the transformation, the vision will look at things in terms of the performance of your products and services, and the processes that support them, for example, or perhaps at the new image the organisation is creating. But you also need to consider some of the softer issues of behaviour, too.

Backwards visioning provides a helpful framework for developing influencing strategies and can be linked with your stakeholder analysis (see the ‘Checking that everyone’s on board’ section earlier in this chapter) and the development of your elevator speech (see the ‘Where are you going?’ section earlier in this chapter). It seeks to create a picture of the future that is expressed in behavioural terms. Improvement teams, for example, need to imagine that their change has been successfully completed. If that were the case, what would they expect to see, both internally and externally, in terms of things such as:

- Behaviours?

- Measures?

- Rewards?

- Recognition?

On a larger scale, what will the transformed organisation look and feel like?

In determining perceptions of these issues, you begin to understand the actions that need to be taken as part of your progress towards the desired state. These will include the activities and behaviours that you need to reduce and remove and those you need to introduce and increase. Progress can really be seen in terms of ‘more or less?’

Locating True North

The vision and the supporting communications need to clearly show exactly what is meant by the organisation’s True North – what it is, where it is, and why you want to be there. You should allow no scope for misconceptions or confusion.

We touched on communication in the ‘Dealing with the soft stuff’ section earlier in this chapter. It’s essential that your approach to communications is appropriate and relevant to the different groups of people within the organisation. In particular, recognise that the communication plan should be tailored to the specific stakeholder groups in terms of format and frequency.

To develop a communication plan, you have to consider some basic questions, such as:

- Why do you want to communicate?

- Who is your audience?

- What message do you want to communicate?

- How do you want to communicate it?

Keeping people focused on arriving at True North means that communication will need to be an ongoing activity. Clearly, as you make progress on the journey, the purpose, audience, message, and formats may change, but the need to keep everyone appropriately informed is vital.

Answering what’s in it for me?

People at all levels in the organisation will want to know the answer to this question, and addressing it in the creation of the stakeholder analysis, the vision and the communications plan is vital.

Ideally, your communication incorporates what the desired answer should be to this question. Get that right and they won’t need to ask the question. The answer they’re looking for will be plain for them to see.

Spreading the word

You need to keep the transformation aims on the agenda and on everyone’s radar. Visual management comes in here. Visual management takes many forms in the workplace and outside of it, too – traffic signs being an obvious example! In the workplace you could use a variety of displays, charts, signs, labels, colour-coded markings, and so on. This helps everyone see what’s going on, understand the process and check that everything’s being done correctly.

Displays and controls could include data or information for people in a specific area, keeping them informed on overall performance or focused on specific quality issues. Visual controls could also cover safety, production throughput, material flow or quality metrics, for example.

Visual management is an essential element in engaging people, securing their buy-in and helping them to communicate performance and progress generally and, in this case, in terms of the transformation journey. Visual management is described in more detail in Lean Six Sigma For Dummies (Wiley).

Everyone in the organisation needs to know where the transformation journey is taking them.

Everyone in the organisation needs to know where the transformation journey is taking them. The A part of the equation is much more important than the Q. Try to get the two parts balanced. So, for example, with Q and A both at 60%, the E is 36%, whereas with Q at 80% and A at 40%, E is only 32%. Getting the A score to at least as high as the Q should be the aim, as these example numbers show.

The A part of the equation is much more important than the Q. Try to get the two parts balanced. So, for example, with Q and A both at 60%, the E is 36%, whereas with Q at 80% and A at 40%, E is only 32%. Getting the A score to at least as high as the Q should be the aim, as these example numbers show.