CHAPTER

3

BOEING

A Struggle to Find Balance in Risk Management

![]()

At any engineering-focused organization, risk management and mitigation are guiding principles. Holistically understanding and appropriately balancing the risks associated with a new endeavor are paramount to a project’s success. These risks come in numerous forms: technical, contract, cost, schedule, safety, etc., and they all matter. This is especially true at Boeing, the world’s largest aerospace company, where the financial bets made on new products are enormous, the technical hurdles are high, and the costs of failure can be catastrophic.

In the last few decades, Boeing went through a transformation. An engineering- and product-centric culture that pushed the boundaries of technology, regardless of financial or business risks, changed to develop a deeper focus on competitiveness and profit generation. The transformation started in the 1990s but didn’t take hold until the 2000s. At that point, financial crises made it necessary for new managers to implement meaningful changes in the way Boeing approached the airplane business. Schedule slips and massive cost overruns generated financial losses that, in aggregate, exceeded the company’s entire market value. Boeing’s long-term health and survival were at stake. Financials were in disrepair, and everything from labor relations to new product development required rethinking.

By focusing on reducing technical and financial risk, the company charted a new path. Each year, financial targets and expectations for future financial performance were ratcheted higher. The stock price followed, making Boeing the most valuable industrial company in the world after decades of being viewed as “uninvestable” by Wall Street. The company’s transformation in the 2010s was undeniable. Boeing went from bleeding cash at an unsustainable rate to generating profits at a level that even the most bullish observers never thought was possible. Many of the changes underpinning the company’s transformation, such as having a deeper appreciation for emerging global competitors and not taking on new, overly risky projects, were relatively straightforward and easy. Other decisions were tougher, requiring meaningful sacrifices from important stakeholder groups. Reducing jobs, closing facilities, pressuring suppliers for concessions, and pushing off all-new product designs for customers inevitably had cascading impacts. All the financial success came with a cost.

Jobs were lost, relationships with suppliers were strained, and eventually two 737MAX planes crashed, claiming the lives of 346 people. Amid the company’s push for lower financial risk and higher profits, it made technical, safety, and public relations mistakes. While attempting to recover from these mistakes, the company maintained an aggressive posture, piling on debt and increasing financial risk. Then, in a stroke of very bad luck, the COVID-19 pandemic brought the company to its knees and on the verge of needing government support to survive.

There is a delicate interplay among a company’s various stakeholders, and improperly balancing the competing demands of disparate groups inevitably leads to failure. This is especially true for an aircraft manufacturer like Boeing, whose responsibilities start with the safety of the flying public and extend from the employment of hundreds of thousands of people to its investors and owners on Wall Street. Boeing needs to be safe, technically proficient, and financially viable. The balance remains tenuous, but the company’s long-term sustainability hinges on understanding and applying thoughtful focus to the unique needs of each group.

UNDERSTANDING THE AIRPLANE BUSINESS

Aerospace companies and their government sponsors have long pushed the limits of engineering and exploration, often to great technical success. They broke the sound barrier, carried astronauts to the moon, and made the world a smaller place for billions of passengers. Nevertheless, Boeing, the company sitting atop the global aerospace industry, struggled for decades to consistently make money.

A new airplane costs billions of dollars to develop and remains in service for upward of 30 years. Massive fortunes are at risk, and there is little room for error. For most of Boeing’s history, technical achievement was synonymous with financial mediocrity. Cost, schedule, and business risks were usually secondary or tertiary considerations. Innovations in materials, design, and manufacturing processes were often pushed forward without a careful consideration or full understanding of what could go wrong later on in the aircraft production process. Corporate cultures became ingrained with bad habits, and decision-making was driven by internal and external politics more than anything else.

To be fair, the airplane business isn’t easy. A manufacturer invests billions of dollars in research and development simply to design a new aircraft and certify it for service. If successful, the company then loses billions of dollars on the first 100 to 200 airplanes as it streamlines complex manufacturing processes and increases volume. After these substantial up-front investments, it then may enjoy several years making billions of dollars when production is mature, pricing is good, and volume is relatively high.

An analysis of a half century of aircraft development programs suggests that bets on new aircraft pay off and make money only half of the time. The other half of the time, poor sales, low production volume, or technical problems and delays lead to significant losses. As a result, until 2010, the industry hadn’t consistently generated acceptable levels of profitability. We estimate that from 1970 to 2010, Boeing generated a paltry average profit margin of just over 5 percent in the airplane business.

This historical mediocrity in returns is largely the result of poorly conceived airplane programs dragging down otherwise good ones. An airplane program is a monumental engineering and manufacturing challenge. Engineers design 500,000-pound pieces of equipment that can fly through the sky at 500 miles per hour, and line workers assemble them at a pace as fast as one new plane per day. Organizations of hundreds of thousands of people invest millions of hours and billions of dollars in bringing a new plane to market. At any given time, an aircraft manufacturer only has the organizational bandwidth to produce a few distinct product lines at reasonable volumes. This makes the mix of money-makers versus money-losers incredibly influential to the company’s overall level of profitability. For almost the entirety of Boeing’s history in the commercial jet business, it had both good and bad programs, due to a culture that focused more on engineering than profitable business.

TWENTIETH-CENTURY BOEING—ENGINEERING FIRST

Boeing has one of the most celebrated engineering cultures in American business history. Walking through an airport, it’s not uncommon to see pilots with a sticker on their flight bags stating, “If it ain’t Boeing, I’m not going,” a marketing tagline reflecting Boeing’s desire to manufacture the world’s most advanced, highest-quality aircraft.

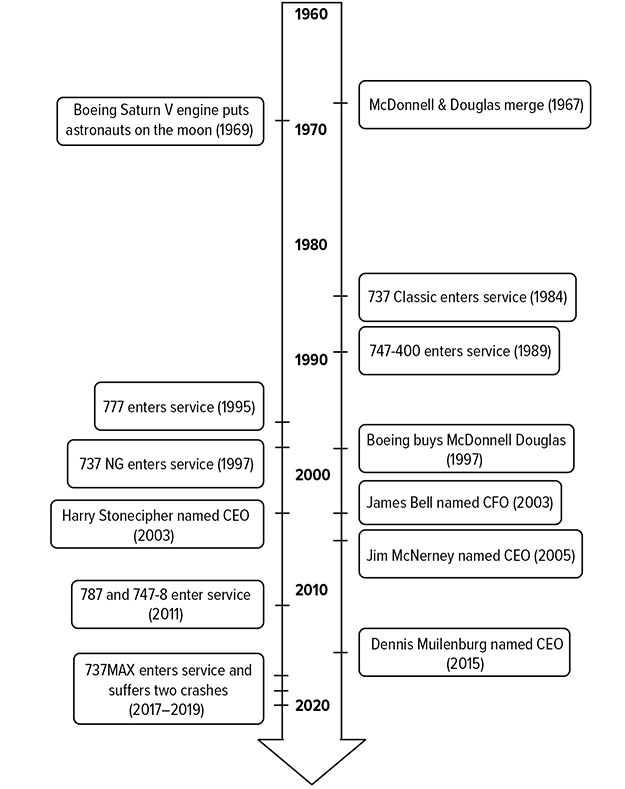

The Boeing 707 and 747 revolutionized jet travel in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s and served as a key source of pride for those who made them. Mainline employees and managers alike saw their engineering capabilities as the unmatched pillar of the company’s success. Boeing amazingly launched three clean-sheet aircraft in the 1960s (the 727, 737, and 747), a feat of developmental engineering that no other aircraft manufacturer has ever approached. Engineering triumphs like these helped solidify Boeing’s leadership position. However, it sometimes seemed that revolutionary engineering accomplishments were the sole goal of the company, regardless of the financial risks inherent in achieving them. That began to change following the company’s merger with McDonnell Douglas in 1997.

Following the McDonnell Douglas deal, Boeing became the undisputed leader of the market for commercial aircraft, with ~70 percent global market share of passenger jets delivered. Yet even with a dominant market position, the company struggled to make money. In fact, during the year of the merger with McDonnell, the new Boeing Commercial Airplanes (BCA) division failed to deliver a profit at all, as it struggled to bring a new variant of the popular 737, known as the 737 Next Generation (NG) to market. The launch and subsequent ramp-up of the new product was beset by delays that ultimately required a halt in production.

When the merger closed, McDonnell CEO Harry Stonecipher joined as Boeing’s president and COO, a job intended to be a preretirement placeholder for the 61-year-old. The son of a Tennessee coal miner, this hard-nosed engineer turned out to be the right executive to steer Boeing through its problems with the 737NG program. He was as tough as they come and immediately clashed with Boeing’s engineering- and product-centric approach to running the business.

During his first visit to Boeing’s Everett factory, Stonecipher looked at a 747 being manufactured for Air India and asked, “How much do we make on that plane?” He was told that the question was not answerable on an individual plane-by-plane basis. He waited months for a better answer and never got one, later proclaiming, “Only one man, the CFO [Boyd Givan], knows how much it costs to build a jetliner, and he isn’t talking.” The 747 was an immensely important product for Boeing, representing nearly half the company’s profits at the time. Yet at the highest levels of the organization, managers didn’t have the detailed understanding of the program’s unit economics that normally would be prevalent at a mature manufacturing company. Not knowing how much money the company was making or losing on each customer’s aircraft demonstrated a lack of financial rigor that he found simply unacceptable. The complexity and scale of aircraft manufacturing leave little room for error, and a program’s success or failure cannot be left to chance. Stonecipher pushed Boeing’s overall CEO, Phil Condit, to fire both Givan and Boeing Commercial Airplanes CEO Ron Woodard in an effort to drive better risk-adjusted focus and discipline across the organization. BCA clawed its way back to profitability a year later, but the underlying issues were far from fixed.

Boeing’s experience with Stonecipher was emblematic of what many outsiders observed over the years: For Boeing, it was all about the airplanes. The engineers responsible for designing the aircraft, along with the line workers responsible for building them, effectively ran the company. Stonecipher contended that the organization needed to be run more like a for-profit enterprise. For the company to be sustainably successful, it needed to have a healthier balance of engineering and financial discipline. Big product bets would always be at the heart of the airplane business, but Stonecipher tried to get the company to evaluate those bets alongside the risks associated with them. This required a more detailed understanding and tracking of the financial implications of engineering and manufacturing decisions. Stonecipher initiated this process, but meaningful changes didn’t come easily or immediately.

Boeing endured a nasty strike later in Stonecipher’s tenure, due largely to strained labor relations that many associated with his internal efforts to wrest some control of the company from the engineering group. Interestingly, the strike wasn’t conducted by the IAM, the company’s blue-collar union of aircraft assemblers, but instead by its engineer’s union, SPEEA. This was unique, as labor relations with SPEEA had traditionally been amicable. However, the late 1990s had proved tough for the engineers. Struggles on the 737NG necessitated more of a focus on day-to-day manufacturing operations rather than new airplane designs, and research and development funding came down accordingly. This didn’t sit well with the engineering crowd, many of whom were simultaneously feeling their status as elite professionals in the Seattle economy wither away with the tech industry’s meteoric rise. In the eyes of the engineers, Stonecipher was the poster child for a management team that no longer understood or appreciated how Boeing did things.

Years after Stonecipher’s departure, a leader within Boeing’s Commercial Airplane segment complained to me that he believed much of the Boeing workforce thought “it was their God-given right to make airplanes, and that’s become a big problem over the years.” While Boeing enjoyed an undisputed leadership position for much of the twentieth century, that position wasn’t set in stone. What many at Boeing failed to fully appreciate at the turn of the century was that the dominant market share the company had enjoyed for the previous four decades was about to be challenged in a major way by the company’s European counterpart, Airbus. While many in the Boeing enterprise still look back on the Stonecipher era as a period of cultural pain, others came to appreciate that Stonecipher was one of the first to see the changing demands on the company’s performance that were arising due to competition. Like it or not, Airbus was emerging as a major global competitor that would force Boeing, an organization that had grown very set in its ways, to meaningfully change its behavior. (See Figure 3.1.)

Figure 3.1: Boeing’s history (1967–2019).

Source: Boeing filings

THE RISE OF AIRBUS, BOEING’S FIRST REAL CHALLENGER

Airbus was formed in the early 1970s through an affiliation of cross-country European aerospace companies in a large-scale partnership called a GIE (groupement d’intérêt économique, a unique form of partnership under French law). This structure allowed for the pooling of economic and manufacturing interests, and it suited the goals of subscale planemakers in France, Germany, and Britain looking to better compete in the global market. As aircraft manufacturers in the United States were gaining significant scale in the 1960s and 1970s, European countries needed to work together. Out of this mutual interest and agreement, Airbus was born.

The company’s formation and initial product introductions were reasonably successful, and yet Airbus didn’t gain real momentum in the aircraft industry until 1985. That’s when Jean Pierson, a colorful, chain-smoking Frenchman who once worked on the famous Anglo-French Concorde program, dared to challenge Boeing’s market dominance.

Pierson oversaw more than a quintupling of Airbus airplane orders during his 13-year tenure as CEO, along with the launch of the successful A320 and A330 programs, planes that sought to beat out Boeing’s offerings at the time. Pierson’s Airbus grew to supplant the only other US aircraft manufacturer of significance, McDonnell Douglas, essentially forcing the merger with Boeing. This merger cemented the global duopoly that exists today.

Boeing spent much of Pierson’s tenure either dismissing Airbus as a competitive threat or complaining how European government assistance allowed it to exist in the first place. This is rather amusing, as Boeing had gained its leadership in commercial aircraft with the US government’s purchase of a militarized variant of Boeing’s first jet, the 707, when the commercial jet market was in its infancy.

As Boeing came to appreciate all too slowly, underestimating Airbus proved to be a giant mistake. While it was true that the Airbus of the 1980s and 1990s cared mainly about supporting regional manufacturing efforts and jobs in Europe, in doing so it built a significant and defensible market position. Airbus developed a family of aircraft more diverse than any of Boeing’s previous global competitors. And its sales focus on non-US airlines, just as air travel demand shifted to the non-Western world, proved valuable.

Just as the new millennium began, Airbus came to the public market as part of the IPO of the European Aeronautic, Defense, & Space Company, or EADS. Airbus had credible aspirations to become Boeing’s competitive equal in the long term, and the 9/11 tragedy indirectly gave it momentum. The attacks on the World Trade Center hit Boeing’s US-centric backlog harder than Airbus’s, and in subsequent years Boeing ceded annual delivery market share to the Europeans. In just six years following the merger with McDonnell, Boeing went from controlling nearly three-fourths of the market to occupying a slight minority position versus Airbus. (See Figure 3.2.) Boeing has never recaptured its previous dominance, and the market for aircraft has been a competitive global duopoly. Boeing believed it was untouchable, and by consistently underestimating the potential for anyone, let alone Airbus, to challenge the company’s market position, Boeing enabled a formidable competitor’s rise. In the years that followed, Airbus and Boeing looked to new product offerings to amplify their growth and solidify their relative competitive positioning.

Figure 3.2: Boeing’s market share steadily eroded.

Source: Boeing and Airbus filings

NEW MILLENNIUM, NEW COMPETITION

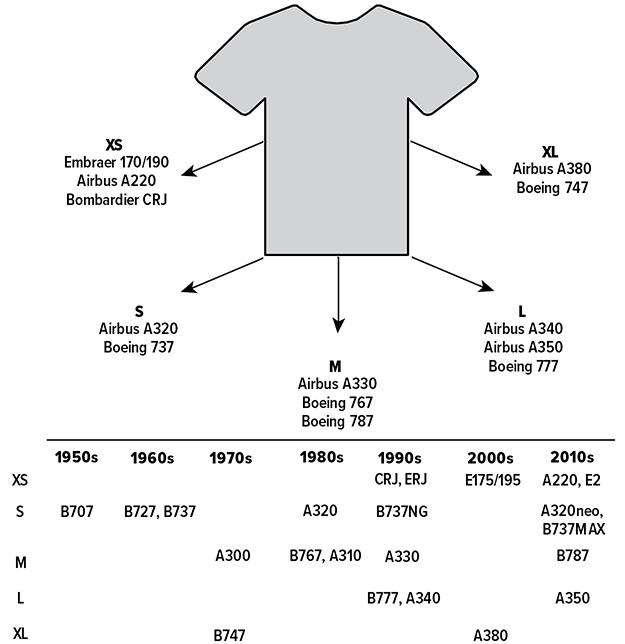

Think of competitive offerings for airplanes as coming in the same sizes as T-shirts: XS, S, M, L, and XL. (See Figure 3.3.) The small end of the market encompasses planes that regular travelers fly on most often, shorter-haul aircraft with one aisle and 3 to 5 hours of flight time. At size medium and larger, aircraft have two aisles and can fly 10 to 15 hours or more over long distances, and in this end of the market, product classes are defined by total seating capacity.

Figure 3.3: Airplane sizes fall in categories similar to shirt sizes.

Source: Company filings, Melius Research

Throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, Boeing enjoyed a monopoly position in the XL end of the market. Boeing’s XL offering was the 747, the double-decker dubbed the “Queen of the Skies.” It was used to shuttle 400+ passengers for up to 16 hours, often between some of the world’s largest cities.

The double-decker 747 entered service in 1970 and went through several upgrades, the most notable being the 747-400 derivative in 1989. The -400 was a popular plane with no direct competition and decades of manufacturing experience and cost reduction. It helped fund the successful launch of the size-L 777 and offset the struggles of the size-S 737NG. When Airbus looked across the Boeing product portfolio, Airbus decided that a competitive response at the XL end of the market made the most sense.

In 2000 Airbus launched the A380, the largest passenger aircraft ever produced. With two full passenger decks spanning the entire length of the aircraft, the A380 aimed to carry 500+ passengers between the world’s booming megacities. The extra size also allowed for a variety of new amenities like swanky onboard bars and even showers for first-class passengers. The plane was hailed as the ultimate step forward for passenger comfort, but it also offered high-density seating configurations that were capable of ferrying more than 800 passengers at one time. As Airbus launched this assault on Boeing’s most profitable aircraft platform, Boeing did not sit idly by.

Airbus had experienced success in the 1990s with the A330/A340 family of aircraft, a codeveloped size-M and size-L product offering, with the A330 dealing a near death blow to Boeing’s 767. Boeing already had newer products in sizes S (the 737NG) and L (the 777), and opted to focus its development efforts on taking back the leadership position from the A330 in the M segment. The members of the engineering team amplified these competitive dynamics, as they wanted to get back to doing what they did best, pushing the technology envelope in new airplane development.

Major technology shifts in the aviation world happen at a decadal pace, and in the early 2000s there were several vectors of technology that warranted exploration. High oil prices, as well as emerging competition from upstart airline competitors known as low-cost carriers (LCCs), had Boeing’s customers clamoring for greater fuel efficiency. Their concerns brought to the fore a new material used mainly in military aircraft and spacecraft production. The new material was carbon fiber reinforced polymer composite (CFRP), or just “composite.” Composite’s strength-to-weight ratio was significantly greater than that of traditional materials like aluminum, which translated to significant weight savings and by extension to fuel savings. Boeing decided to manufacture an airplane that was thinner, stronger, and up to 25 percent lighter than metal by building it entirely out of composite.

Boeing initially called the new aircraft the 7E7, with the “E” standing for efficiency. Innovation efforts didn’t stop with the aircraft structure. Boeing also elected to make the 7E7 the world’s first aircraft using all-electric subsystems rather than hydraulic or pneumatic. This drove further weight savings and greater power efficiency from the engines, adding to the fuel savings. The 7E7, later rebranded as the 787 Dreamliner, was precisely the sort of technology moon shot that defined the engineering-centric culture of Boeing’s past. It was billed as a superefficient enabler of point-to-point connectivity for airlines, packed with every bit of cutting-edge technology that the company could imagine.

In addition to the grand scale and innovative technologies embedded in the all-new 787, the manufacturing plans involved a great deal of geographic fragmentation. The company outsourced production around the globe, often to greenfield sites that had never constructed anything for an airplane. To make the production system work, Boeing built a small fleet of modified 747 freighter aircraft (called Dreamlifters) to fly giant sections of the aircraft to Seattle for final assembly. Boeing’s engineers were reinventing not just what airplanes were built with, but also how they were built. Like everything else on the 787, it sounded like a good idea on paper, but it would prove otherwise. (See Figure 3.4.)

Figure 3.4: The 787 global outsourcing was unprecedented.

Source: Boeing filings

THE 787 DEVELOPMENT BEGAN TO UNRAVEL

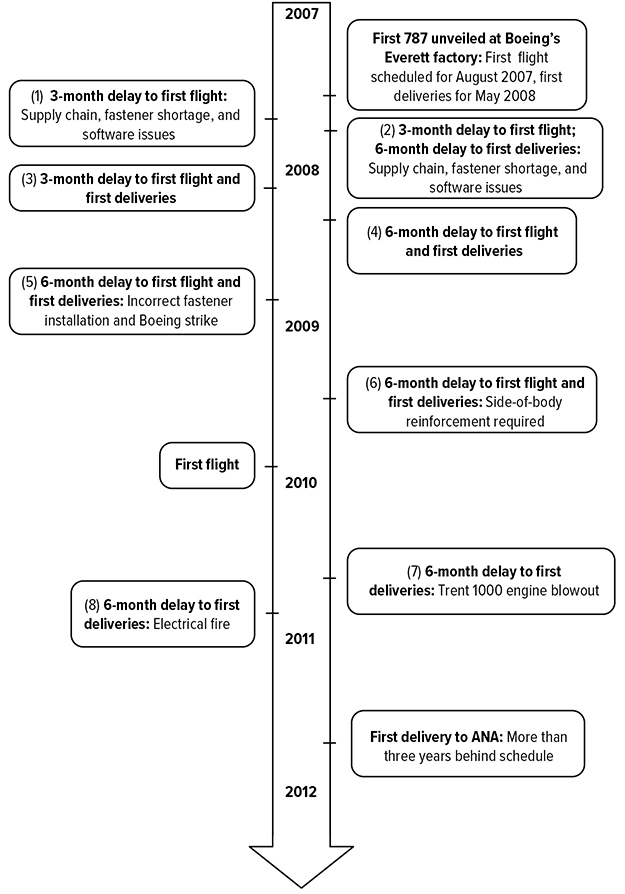

The Beijing Olympics were scheduled for summer 2008, and Boeing wanted the 787 to shuttle passengers to the event from the farthest reaches of the globe. If that wasn’t a frivolous enough target for such a major project, someone in the marketing department determined that the perfect date for rollout of the first “completed” aircraft was July 8, 2007, or 7/8/7. Boeing organized the program’s schedules and timelines around these events, whether realistic and achievable or not.

The 787 did indeed roll out on 7/8/2007 to throngs of observers in Everett, Washington, but the plane was far from complete. Some fuselage sections didn’t fit together properly, parts of the wings were made of painted wood, and the plane lacked a working electrical system. A CEO of a major 787 supplier told me years later, “When I saw light shining through unfilled holes in the fuselage, I knew this thing was an unmitigated disaster waiting to happen.” Nevertheless, the schedule was the schedule, and Boeing admitted nothing in the way of problems or delays. That first airplane was built, taken apart, and rebuilt three times. It cost more than $1.2 billion by the time it was “done,” well more than 10 times its intended selling price.

The 787’s first flight was supposed to happen in August 2007 (shortly after the 7/8/7 rollout), but it didn’t occur until December 2009, more than a year after the Beijing Olympics. Boeing announced eight delays to the program’s schedule, and the first deliveries to customers didn’t happen until 2011, three years later than planned. Aircraft up to the sixty-sixth off the line were referred to internally as the “terrible teens” because they required so much fixing that they weren’t all delivered until seven years later, in 2018. Like stubborn kids, they took a long time to leave home. (See Figure 3.5.)

Figure 3.5: The 787 was delayed eight times.

Source: Boeing filings, press reports

Boeing ultimately spent $20 billion on R&D for the 787, but that was just scratching the surface of how much money went out the door before things got under control. Besides the R&D expenditures associated with the program, the company lost an additional $28 billion manufacturing the 787 before the first profitable plane rolled off the line in 2016. This brought total cash out the door to roughly $50 billion, making the 787 investment a bet that was twice the size of the company’s entire market value at the time of its launch in 2003. Despite significant technological advances, robust sales, and a product that ultimately was well received by the customer, the 787 was by far the biggest financial failure in the company’s history. Along the way, it ended the careers of numerous executives and put the company’s financials under enormous strain.

To make matters worse, while the 787 development was ongoing, the company decided to launch an update to its aging 747, called the 747-8, to counter the A380. It featured a longer fuselage and took on the 787’s new GEnx engines from GE to improve fuel efficiency. In hindsight, this was purely a vanity project aimed at stealing some market share back from the A380, and it failed miserably. The 747-8 program faced manufacturing delays of its own, which was a particularly embarrassing outcome since the -8 variant was a relatively simple update of a plane the company had been building for over 30 years. The program was an inefficient use of Boeing’s engineering, manufacturing, and financial resources at a time when the 787 was bleeding massive amounts of cash. Boeing aircraft margins fell from ~10 percent in 2005–2006 to ~3 percent in just three years, and the company’s total cash flow fell by more than half, with no signs of pending improvement. As a result, efforts to reverse course and improve financial performance became necessary to ensure that the company would remain a going concern.

DIAGNOSING WHAT WENT WRONG

In the midst of these crises in 2010, I attended a breakfast with Boeing’s then-CEO Jim McNerney, who joined the company in 2005 after serving for two years on the company’s board. McNerney was a high-level thinker who was well equipped to conceptualize the causes of the company’s recent failures. I asked him bluntly what he thought had gone so wrong, and he candidly said the company had too often pushed technology development much further than customers were willing to compensate Boeing for. In the case of the 787, manufacturing a composite airplane cost significantly more than the company ever imagined, and the technical risks that BCA was willing to take to deliver maximum fuel efficiency were a stretch too far. If that weren’t enough, outsourcing massive parts of the production served as the death blow for the program’s financials.

In McNerney’s view, customers were willing to pay for the improved performance of new aircraft if it translated to fuel savings or greater range, but they certainly weren’t going to help foot the cost of development overruns. In fact, they expected exactly the opposite—they wanted to be compensated for delivery delays due to poorly executed development efforts or technological overreach. McNerney coalesced Boeing around a new strategic direction, one he later coined, “de-risking the decade.” Up to that point, risk mitigation and financial stability weren’t high on the list of priorities. The company’s culture assumed that if you designed a great airplane and sold it well, everything else would take care of itself. This long-held mentality led to a major misalignment between internal and external stakeholders and to a decision-making process around everything, from product development to how employees and managers were paid, that created incongruent outcomes. Strikes and labor unrest were common, financial performance was poor, and financial charges were commonplace. No one had a good sense of what the company’s level of profitability could be; there was no benchmarking of significance. McNerney sought to reverse these trendlines on numerous fronts.

The de-risking began with a focus on working through money-losing contracts without signing up for any new risky work. Then the company went through broad-based “should-cost” exercises that evaluated functional elements of the Boeing cost structure in painstaking detail, and for the first time it benchmarked the elements against outside data. Corporate incentives also underwent a sweeping overhaul to focus on manufacturing, financial execution, and alignment with total shareholder return. These efforts to contain cost, limit risk, and benchmark and incentivize appropriately, all while constantly examining results and refining the strategy, reoriented Boeing around a new set of guiding principles.

Boeing’s focus on de-risking and operational improvement seemed well timed, as Airbus, under new CEO Tom Enders, was engaged in a similar exercise. Airbus had its own near-death experience with the A380, and the wild currency swings of the 2000s left Airbus searching for competitiveness and sustainable profitability as well. This simultaneous risk-adjusted approach to management was best evidenced by the decision of both companies to simply re-engine their two most profitable airplanes rather than design entirely new ones.

In 2010, Airbus and Boeing both had two main profit centers in the airplane units, their single-aisle offerings (A320 and B737) and their twin-aisle offerings (A330 and B777). In the years leading up to this point, Airbus had responded to the 787 by launching an all-new aircraft, the A350XWB, which kept the engineering team busy. Having already developed the 787, Boeing was exploring the idea of allocating its future research and development spending on a new single-aisle replacement for the 737, called the NSA, or New Small Airplane.

Enders and the team at Airbus realized that they needed to stretch the engineering resources of the firm beyond what was prudent in order to fully respond to Boeing if it launched the NSA. Simultaneously, they figured out that by putting newer, more fuel-efficient engines on the A320, they could achieve a significant amount of any efficiency gains the NSA promised for a fraction of the development cost, all while leaving enough engineering resources in place to de-risk the development of the A350. The A320neo (short for “new engine option”) was born.

Airbus sold the A320neo at a pace that took the aviation world by surprise, amassing more than 1,000 aircraft sales in just over six months. Boeing initially dismissed the need to respond to the A320neo’s success until longtime Boeing customer American Airlines was on the verge of signing an order for 500 A320neos. Overnight, Boeing scrapped the NSA concept and agreed to launch a re-engined version of its own 737, salvaging half the American Airlines order in the process.

In the years that followed, both companies expanded the re-engining effort to their profitable widebody aircraft (A330 and B777). Unlike the well-trodden “lose billions and maybe make billions” path of clean-sheet aircraft development, re-engining saved billions in up-front development expenses when cash was a scarce commodity due to the failures of the 787, 747-8, and A380. It allowed Airbus and Boeing to continue to sell their mature products at higher volumes and higher prices over a longer period of time.

The re-engining decisions were emblematic of the industry’s newfound appreciation of pursuing bigger profits while taking less risk. It was a stark change from behaviors of the past, but following a lost decade of financial performance in the 2000s, the change in strategic direction was both inevitable and well placed.

LOWER RISKS, HIGHER PROFITS

When I began covering the aerospace sector in the early 2000s, then-Boeing CFO James Bell cited a 10 percent operating margin rate as an aspirational goal for the company. Bell’s logic was that since 10 percent was the best the company had ever generated in the past, it must represent the upper bound for the future. However, on the back of McNerney’s de-risking focus in the early 2010s, Boeing concluded that the mid-to-high-teens margins achieved by other best-in-class industrial peers were achievable. The company instituted new approaches aimed at driving further improvement in sustainable profit margins.

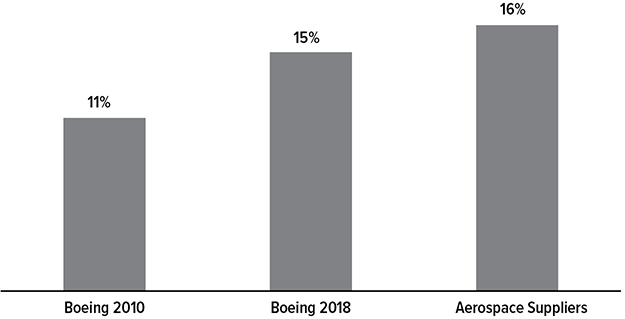

Under McNerney’s watch, Boeing launched several initiatives focused on improving cost competitiveness. Realizing that outside suppliers dominated the company’s cost structure and that supplier’s margins were 50 percent higher in many cases, the company created “Partnering for Success,” or PFS. Under PFS, Boeing aggressively pushed suppliers to lower prices or risk being cut out of future platforms. Privately, supply chain partners referred to the initiative as “Pilfering from Suppliers,” but they grudgingly went along with the effort. After all, Boeing controlled the intellectual property and took the lion’s share of development and production risk. (See Figure 3.6.)

Figure 3.6: Boeing profitability establishes a new normal, approaching supplier levels.

Source: Company filings

Inside Boeing’s factories, the company used cross-site comparisons of manufacturing operations called “Champion Times” to rapidly improve productivity. It granularly compared common manufacturing jobs performed at different sites and calculated which workers performed the job in the shortest amount of time. Then it studied the specific behaviors that generated the best outcomes and implemented best practices across the organization in order to replicate them. Furthermore, it invested aggressively in robotics and automation technology, taking people out of the manufacturing organization in certain areas.

As this new path forward for Boeing emerged, financial progress followed. After losing billions of dollars that would never be fully earned back on the first 500 to 600 planes, the 787 went from severely loss-making to breakeven. At the same time, sales volume on the highly profitable 737 rose by a third, absorbing more fixed costs, with productivity gains expanding margins further. Demand for single-aisle airplanes boomed alongside the rapid growth of the global middle class, and strong demand drove higher aircraft pricing. Efforts to reduce supply chain costs hit the bottom line, and the company worked hard to limit growth in fixed costs. Boeing earnings were on a path to doubling or even tripling by the end of the decade.

However, somewhere along the path to great financial success, the company began to lose sight of creeping risks. Those risks would have materially negative consequences for key nonfinancial stakeholders.

“THE EMPLOYEES WILL STILL BE COWERING”

Boeing always had a mandatory retirement age of 65 in place for CEOs, a rule intended to ensure that leadership changed hands at regular intervals. But when Boeing CEO Jim McNerney was approaching 65 in the middle of the 2010s, he wasn’t ready to retire just yet. The company was still in the early stages of its transformation, and 2016 would mark the company’s 100-year anniversary, a milestone he wanted to reach.

Around that time, as part of the company’s newfound religion on cost control, McNerney and his team were looking to secure deals and concessions not just from suppliers but also from employee unions. These deals were initially aimed at improving Boeing’s long-term cost competitiveness. The negotiations were contentious and unpopular, but they were necessary to get the company on more solid footing. One of the company’s chief risks was out-of-control costs from pension plans put in place decades earlier. Boeing’s pension plan was the second largest in America at the time and was underfunded by ~$20 billion. Every year, pension benefits owed to workers ballooned. Stemming the tide of pension cost growth was essential to getting the long-term cost structure under control.

An opportunity to address the pension problem eventually presented itself. On the back of the successful launch and early sales of the 737MAX, Boeing repeated the re-engining strategy with the 777 program, formally launching the 777X. This updated version of the plane would feature new composite wings and larger, more fuel-efficient engines. The plane’s design was settled on rather quickly, but where the new version of the aircraft would be assembled remained an open question.

The existing 777 assembly line was just outside of Seattle and seemed the logical choice for the 777X. But Boeing’s recently acquired nonunion site in South Carolina was an attractive alternative. The company would use this alternative production site as a bargaining chip in labor negotiations.

A contract negotiation with Boeing’s largest union, the International Association of Machinists & Aerospace Workers (IAM), was ongoing, and Boeing wanted the workforce to give up pension benefits for future employees in exchange for keeping 777X work in Washington State. The strategy worked and helped to address the single largest cost problem on Boeing’s hands. Yet it strained relations between management and the unions.

While he never said it outright, I always took away from my conversations with McNerney that labor relations were strained for good reason. After all, in 2008 the IAM had gone on strike in the middle of the biggest economic malaise since the Great Depression. It was a bold and poorly timed move by the union, as the economic downturn was compounded by mounting production struggles with the 787. This was almost certainly something that McNerney never forgot.

Not long after the labor deal was done, Boeing’s board of directors granted McNerney’s request to stay beyond the mandatory retirement age of 65. When he confirmed this extension on the next earnings call, he noted that he was staying longer and that “the heart will still be beating, and the employees will still be cowering.” He later apologized, but the message was loud and clear.

McNerney’s statement was symbolic of the contentious relationship with labor that resulted from actions taken to help the company recover from the 787’s failures. Tough decisions often require sacrifice, and a hard-nosed approach with lingering impacts on various stakeholder groups needs to be thoughtfully considered. This fracture with labor is the first major instance that I can recall when the needs and desires of other key stakeholder groups appear to have been completely forgotten or ignored.

This example may have just been a one-off occurrence, but it certainly stood out as clear evidence that management wasn’t messing around. As leadership of the company transitioned from McNerney to Dennis Muilenburg, there were budding signs of stress with other stakeholder groups. McNerney moved to the chairmanship of the board as Boeing approached its hundredth anniversary, with the company’s financials delivering consistent improvement. Muilenburg was forced to figure out how to make them even better.

A NEW BOSS PUSHES FOR HIGHER HIGHS

Dennis Muilenburg was promoted to chief operating officer just before Christmas of 2013, coming from leading Boeing’s defense business. The first 15 years of his career were spent at the Boeing Commercial Airplanes unit, as an engineer and program manager, making him well seasoned in all things Boeing. With this promotion he became the heir apparent to McNerney.

Muilenburg’s most recent success came from overseeing a dramatic cost-cutting effort across the 60,000-person Boeing Defense enterprise, an approach called “market-based affordability.” While externally the Boeing defense business wasn’t getting the same attention as the commercial airplane unit, internally Muilenburg’s success in rapidly reducing costs wasn’t going unnoticed. While he was viewed by some of the other executive leaders as aloof and not fully in sync with the needs of the wider organization, his star was undeniably on the rise. McNerney admired his “can-do” attitude and saw Muilenburg as an executive who would push the organization to achieve higher financial highs.

In the commercial airplanes segment, some in the leadership ranks believed that if Muilenburg pursued a similar effort to aggressively reduce head count in their unit, it would prove more problematic. For these managers and employees, the integrity and achievability of the aircraft production plan were paramount, especially given the lessons learned on the 787 in the preceding years. Schedule and customer satisfaction needed to be the primary objective. This tension would prove important later on.

By the time Muilenburg moved to the CEO role two years later, it was becoming clear that expanding margins and growing cash flows were the company’s principal financial opportunities. Boeing’s decision to forgo building completely new aircraft designs, and instead focus on fixing its money-losing programs, meant that a dramatic improvement in profitability was effectively locked in for the coming years.

Muilenburg announced a commitment to increase operating profit margins from ~9 percent to “mid-teens,” along with a plan to grow cash flow every year for the foreseeable future. Wall Street fell in love with the message, and the stock rose by ~40 percent during Muilenburg’s first two years as CEO. While much of the success was based on structural improvements across the business, head-count reductions were also a contributing factor. The workforce declined by 13 percent in total and by 15 percent in the commercial airplanes unit. But unlike the cuts at Muilenburg’s defense unit in prior years, when sales were declining, the head-count reduction in commercial airplanes occurred while volumes were rising. (See Figure 3.7.)

Figure 3.7: Boeing’s head count fell by 20,000+ even as sales grew.

Source: Boeing filings

By the time Muilenburg reached his third year at the helm, the financial performance was so good it was almost unbelievable. During one quarterly earnings release in the summer of 2017, Boeing indicated that it expected to beat its full-year cash flow plan by $2 billion, while reiterating its previous commitment to grow cash flow every year. The baseline for 2017 and every year after moved up by $2 billion, and shares rose by roughly 80 percent in the subsequent year. Boeing became a must-own stock. Muilenburg was named Aviation Week’s Person of the Year and was featured on the cover of Bloomberg Markets magazine with the title “Up, Way Up.”

IF A LITTLE IS GOOD, MORE MUST BE BETTER, RIGHT?

In the wake of Boeing’s success in expanding profit margins and cash flows, there was a palpable desire to determine what else could be achieved in the future through an expansion of similar efforts. The company launched PFS-2, asking suppliers not just for lower prices but also for more lenient payment terms in new contracts. The move effectively leveraged Boeing’s negotiating power to shift more value away from the supplier base and into Boeing’s pockets and further fueled the cash flow growth it had promised investors.

Tensions between Boeing and the company’s supplier base grew; yet the company pushed forward, undeterred. As a mechanism for enforcement, it explored a wide range of manufacturing insourcing efforts. The prospect of being able to credibly take work back from suppliers and perform it in-house was a serious threat for firms making good money producing parts for Boeing.

At first the insourcing threat sounded strategically savvy. Boeing had a good understanding of the technology that went into its airplanes. However, understanding the technological specifications and delivering manufacturing excellence are very different things. Many of Boeing’s suppliers had spent decades optimizing their production systems for parts that Boeing hadn’t manufactured on its own in a long time, if ever.

In 2017 I toured one of the sites performing insourced work for the 737MAX that on earlier 737 versions was done by an external supplier. At the end of the tour, I was shown a chart detailing that Boeing’s cost per part was at least 30 percent below the prices offered by suppliers A, B, C, and D. One of these suppliers was the previous manufacturer. This seemed odd, as the legacy supplier would have the benefit of decades of manufacturing experience for a component that Boeing only recently started building. This conclusion defied common sense and the well-understood and time-tested principle of manufacturing learning curves.

In a later discussion with a retired Boeing executive, I asked how the math in this insourcing example might be possible. He said that it couldn’t be and that the company was simply fooling itself, likely altering the cost calculations in such a way to prove to itself that insourcing must be better. The supply base had to be cheaper on an honest, apples-to-apples basis. But if Boeing convinced itself otherwise, that’s all that mattered. The company could decide to insource work even when it didn’t make sense to do so. This only served to strain supplier relations even further.

Boeing’s aggressive posture didn’t stop with unions and suppliers. It expanded into the political realm in 2017 when the company pushed the US government to levy massive tariffs on a new regional jet known as the C-Series being introduced by Canadian competitor Bombardier. The effort was widely seen as an attempt to kill off the program before it gained commercial momentum. In the end the effort backfired: the pressure sent the C-Series program into the waiting arms of Airbus, which acquired the rights to the new aircraft in 2018. Under Airbus’s ownership, the competitive threat posed by the program only increased.

Throughout the Boeing enterprise, the increasingly contentious relationship with numerous stakeholder groups was bringing unintended consequences. Financial performance was still improving faster than expected: margins in the airplane unit eclipsed 15 percent by the fourth quarter of 2018, and annual cash flow had grown by about two-thirds since Muilenburg took over. Yet there was creeping evidence that Boeing was starting to lose sight of the holistic approach to risk management that had driven the company’s recovery from the struggles of the 2000s.

CRACKS BEGIN TO FORM

The A320neo aircraft, the principal competitor of Boeing’s 737MAX, was certified for commercial use in late 2015. This was more than a year ahead of when Boeing’s plane would be certified for passenger service. This put pressure on Boeing to ramp up production of the MAX as quickly as possible to keep up with its primary competitor. As such, the 737MAX production plan envisioned the steepest ramp-up in the company’s history.

The 737MAX received certification in March 2017, but unlike the smooth production increases executed in prior years, Boeing struggled with the MAX ramp-up. Some believed that the aggressive head-count reduction efforts intended to boost profitability had gone too deep, putting unnecessary stress on the system at precisely the wrong time.

Just before the production ramp-up began, Boeing hired an outsider from GE named Kevin McAllister to serve as the CEO of the Commercial Airplanes unit. He was known as a “customer guy,” brought in to help Boeing achieve its longer-term commercial ambitions. He wasn’t the factory floor guru that the organization really needed as it increasingly struggled to meet the demands of the MAX production schedule.

Under McAllister’s watch, dozens of planes stacked up outside the factory awaiting engines and other parts. Production discipline slipped, both inside Boeing’s factories and at suppliers. But given the increased tensions between Boeing and the company’s supply base, the path toward fixing the situation became more defined by finger-pointing than partnership. During this time, attention that McAllister should’ve been devoting to the factory floor was spent advocating for a new aircraft program with questionable returns.

McAllister was pushing for Boeing to formally move forward with an all-new plane called the Next Midsize Aircraft, or NMA. The plane was intended to serve a segment of the market that the current offering of small and medium-sized planes did not fully cover. But the business case for the product was weak. It was challenging to confidently see how the plane could ever be profitable, let alone generate anywhere near the same level of profitability of Boeing’s existing portfolio of aircraft. At the very least, its launch would certainly add more risk to the overall system, a system that was already showing signs of strain.

Budding problems weren’t confined to the airplane business, as the company’s defense business was beginning to struggle as well. The last remaining troubled contract from the 2000s, one that required Boeing to deliver aerial refueling planes to the US Air Force, was becoming a bigger and bigger problem. The company struggled to get work completed on the first wave of production aircraft. Over a three-year stretch, it took a financial write-off on the program in 9 of 12 quarters. There was no program anywhere else in the entire US defense industry with such a consistent string of negative financial charges.

Luckily for Boeing at the time, the upside elsewhere in the business was so strong that investors looked past the tanker charges and other issues as one-offs to be ignored. Cash flow continued to grow handsomely as the 787 program turned the corner and began to produce profits. The stock went even higher. In the eyes of investors, Boeing could do no wrong. (See Figure 3.8.)

Figure 3.8: Boeing cash flow grew from $3 billion to $15 billion.

Source: Boeing filings

Late 2018 represented a peak in Boeing’s aggressive posture in going after new business. In an unprecedented move for a major defense contractor, Boeing won two competitions to build military aircraft by bidding to lose money, insisting that it would “make it up on volume” in the future. In my career, I’d never seen a company take a financial charge on a program that it had yet to start work on.

At the time, the company made it clear that it believed that the success of the commercial airplane franchise allowed it to cross-subsidize defense bids in a way that was strategically unique and valuable. To me, it seemed unnecessarily risky. However, all these creeping signs of lost risk management discipline would fall from focus when a bigger emergency occurred.

THE MAX CRISIS SUDDENLY CHANGES EVERYTHING

In 2019, following two crashes of the 737MAX, Boeing found itself in a full-blown crisis when it was revealed that a new automated flight control system was the common link in the accidents. The system, known as MCAS, was new to the 737MAX and was foolishly designed to engage based on the input of a single external sensor, something rather uncommon in the aerospace engineering world, which values the safety benefits of redundancy. When engaged, the system pushed the plane’s nose downward to prevent the plane’s angle of attack from getting too steep. However, if engaged at low altitudes, it proved to be dangerous. Furthermore, the system was included without explicit instructions to MAX pilots about how it worked. In both accidents, a failure to disable the MCAS system’s forceful nose-down commands resulted in both aircraft crashing, claiming the lives of 346 passengers and crew.

Following the first of the two crashes, Lion Air Flight 610, Boeing was publicly dismissive of any major issues. Yet behind the scenes, the company was preparing a software modification for MCAS. Evidence of improper maintenance on a key sensor and potentially falsified service records by Lion Air made it difficult to single out Boeing’s flight control software as the singular root cause of the crash. However, when the second plane, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, went down four months later, alarm bells began sounding in the ears of 737MAX operators, global regulators, and the flying public. At least initially, the company maintained a defiant posture in the face of criticism and calls for the 737MAX to be grounded from service.

The MAX was grounded first by China, then in every other region of the world except the United States; Boeing pushed the FAA hard to keep the plane in service until satellite data provided enough evidence to indicate that there was a common link between the two crashes. Boeing’s insistence that the plane was completely safe was tone-deaf to the concerns of the flying public and grossly inaccurate.

Once Boeing finally relented, nearly 400 MAX aircraft were grounded around the world. In the months that followed, a Department of Justice investigation surfaced internal communications that revealed unacceptable levels of pressure on employees to bring the MAX to market as quickly and as cheaply as possible to compete with the A320neo. Furthermore, the MCAS system was exposed as irresponsibly conceived and poorly integrated into the training regimen of MAX pilots. Critics blasted the company’s insistence that iPad training, rather than time spent in a simulator, was sufficient. Yet Muilenburg remained bold and dismissive and struggled to connect with the broader public in a way that demonstrated believable remorse.

Crashes of new aircraft types have happened in the past, but none of them have happened in the social media era. The proliferation of the internet created a world where the flying public has endless access to the details of the accidents, and informed and uninformed opinions are readily available in every corner of Twitter and Facebook. Historically, Boeing communicated only on a business-to-business basis with its airline customers. The 737MAX crisis forced the company to rapidly change and to address passengers directly on new communication channels. This represented a completely new challenge for Boeing, one that its executives botched. At best, they were caught flat-footed, and at worst they were incapable of appreciating the severity of this new risk to the business. The flying public was a key stakeholder group whose safety and confidence they weren’t treating with the appropriate level of care and concern.

When the grounding began, Muilenburg assumed that a return to flight would happen in relatively short order, when the software update being contemplated after the Lion crash was completed. Muilenburg insisted at the company’s annual shareholder meeting that the single-sensor determination was “consistent with [the company’s design] processes.” However, as the FAA and other global regulators scrutinized not only the MCAS recertification and the single-sensor determination, but the aircraft more broadly, the timeline for the MAX’s reentry grew increasingly uncertain. Boeing instructed suppliers to keep producing parts, and MAX production continued even as the timeline began to slip. Hundreds of finished airplanes worth more than $10 billion were placed in company parking lots, awaiting recertification and delivery to customers.

Surprisingly, as pressure on the MAX recertification mounted, Muilenburg was still spending time working on future business projects like the NMA and an exploration of the urban air mobility market through a partnership with Porsche. It wasn’t the behavior of a CEO well versed in how to handle a crisis. In fact, it was just the opposite. His lack of engagement with the FAA during this time led to a reprimand by the regulator, a message to Boeing and to the broader public that the MAX’s timeline for certification wouldn’t be dictated by anything other than the principles of flight safety. Shortly following this event, the Wall Street Journal reported that the meeting between Muilenburg and the FAA where this message was delivered was the first face-to-face encounter he had with the regulator during the entire grounding. The lack of personal connectivity was shocking.

The company booked billions of dollars in financial charges related to the MAX grounding, covering both the costs of lower factory productivity and compensation to airlines that couldn’t use their airplanes. Like the 787 did just a decade before, the MAX ultimately brought with it lessons that will shape the company’s future.

With Muilenburg catching the ire of the FAA, the Boeing board of directors, frustrated by his ineffective management of the crisis on multiple fronts, fired him, but arguably long after the board members should have. Board chairman David Calhoun was appointed as the firm’s new CEO. Initial efforts under Calhoun’s leadership seemed to represent a reversal of the company’s stance on numerous fronts. Boeing quickly backed away from any appearance of forcing the FAA’s hand on recertification by setting a more conservative timeline for the MAX’s return to flight. Additionally, in a complete 180, it recommended simulator training for all MAX pilots to ensure MCAS familiarity. The NMA project was dropped as part of a broader rethinking of what future product development processes should look like, and PFS was eliminated from the vocabulary of those in supply chain–facing roles. Boeing realized the need to focus on rebuilding trust with the stakeholder groups (regulators, employees, suppliers, the flying public) that had taken a backseat to shareholders for an extended period of time. Sadly, these actions were lost in the noise of the COVID-19 global pandemic, which only two months into Calhoun’s tenure called the company’s future into question.

To continue to produce MAX aircraft during the grounding, Boeing took on billions of dollars in debt and swung from a position of net cash to a position of net debt for the first time since the 787 crisis earlier in the decade. Funds supported ongoing MAX production in the supply chain and payments to customers for delivery delays. The company essentially made a bet that when recertification occurred, cash would quickly begin to flow and debt could be repaid.

The COVID-19 outbreak put unprecedented pressure on global air travel. Airlines swiftly cut capacity by 80 or 90 percent in some cases. With no one flying, airlines had little or no cash coming in, and cash payable to Boeing was suddenly in question. In hindsight, Boeing’s bet on a quick recovery was incredibly unlucky and ill-advised, and it left the company seeking government support, something unimaginable when the company’s stock was soaring to all-time highs just before the MAX crisis only a year earlier. The swing from the world’s most valuable industrial company to one whose liquidity and solvency were being questioned in such a short period of time is still mind-boggling.

While almost no one foresaw the extent of the impact that a global pandemic could have on the market for airplanes, it undoubtedly will redefine how everyone evaluates the future. And just like the crises that preceded it, it will forever reshape how the company and all its stakeholders evaluate risk.

POSTMORTEM

Over much of the last three decades, Boeing has struggled to effectively balance the needs of key stakeholder groups, overemphasizing the importance of one or two for extended periods of time. An internally focused engineering- and product-centric culture attained impressive technical achievements, gained outsized market share, and ushered in a period of unprecedented air travel safety. But a lack of financial rigor created an inefficient organization prone to massive economic losses. Market share eventually eroded, and financial health deteriorated under the weight of poor execution and ill-advised development programs. The company was forced to shift its focus to risk mitigation and improved financial performance.

Through a series of deliberate and well-thought-out actions, Boeing improved efficiency in its factories, retired program risk, mitigated development risk, and reclaimed economics that had been lost to the supply chain. It was a real success story. However, an outsized focus on delivering higher financial highs eventually frayed relationships with suppliers and employees and played a role in the tragic loss of 346 lives. Then, a still-aggressive approach to recapture what was lost ran into the most severe crisis in the industry’s history. These mistakes were born not of nefarious intent, but rather of a complacency that emerges when an organization experiences success and doesn’t rebalance itself to ensure it is effectively satisfying the needs of all stakeholders. Safety, quality, and profits aren’t mutually exclusive, but consistently delivering on all of them over the long run requires vigilance and constant recalibration. To be truly successful in the future, Boeing has to find a way to successfully manage all these needs simultaneously.

That’s also true for many companies in the tech world. Most of them are engineering- and product-centric, and as their markets mature with slower growth and normal profitability, they’ll have to confront the same challenge of ensuring profitability without jeopardizing safety and customer value. Additionally, while Big Tech doesn’t grapple directly with safety risks and the loss of human life, issues of customer privacy and social influence are similarly meaningful and only growing in significance. Drawing the lines on customer data use and weighing them against the pursuit of profit and higher share prices is a similar evaluation. It’s inevitable that the influence of nonfinancial and nonemployee stakeholders will only continue to rise in the future. And the industry is not immune from its own megacrisis. In fact, cybersecurity threats for Big Tech could prove to be the equivalent of a global pandemic for industrial firms and travel-focused companies.

Boeing’s task in the 2020s is now unprecedented. Successfully recovering from the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic dominates the focus in the short term. Finding a stable financial position and building a sufficient cash buffer for future crises will inevitably be a primary focus for several years. However, this effort has to come alongside managing safety and quality risks first, while not losing discipline on the cost, schedule, and development fronts. New products will be required in due course, but they can’t come at the expense of long-term cost competitiveness and financial viability. Similarly, relationships with suppliers and labor have to be carefully structured to ensure operational and financial success without causing disruption. One thing is for certain: more crises lie ahead. The question is whether Boeing’s century-old franchise can evolve to manage the crises of the future without forgetting about balancing and sustaining the gains from the past.

Lessons from Boeing