CHAPTER

7

CATERPILLAR

Avoiding the Forecasting Trap

![]()

Caterpillar is one of the industrial world’s best-known brands, with its yellow bulldozers and excavators visible on construction projects around the world. As of 2019 more than a hundred thousand people worked at CAT, and the stock market valued the company at $80 billion—but those numbers could have been much higher. The company just recently came out of a two-decade-long stretch with painful periods of poor performance and destructive acquisitions.

Great industrials have endured through continuous improvement—a slow, iterative process with increasingly huge benefits as time goes by—the benefits of which are locked in as competence becomes ingrained across the employee base. Caterpillar’s experience illustrates the depth of the problems that can arise when a systematic culture and operating system isn’t present in a large organization. Without that, a company is forced to try to manage by feel, using forecasting and intuition to guess demand. In a cyclical industry, staying true to Lean is even harder, but also more important. There are some booms and busts in the end markets in this case study, but they aren’t the focus. Rather, it’s how CAT dealt with them and how that accentuated the volatility.

CAT lost out on billions in potential revenues and earnings by having inadequate management systems. Competitors took advantage, using their own Lean and flexible production to enter markets that had been CAT strongholds. CAT then made the mistake of overcorrecting, losing billions more in potential earnings. Instead of large profits compounding in fruitful acquisitions, CAT reinvested its lower earnings base poorly, with billions spent on acquisitions that deliver negligible sales today. Skittish investors now value its current earnings below those of its industrial peers, making for another missing pool of billions of dollars. This was a spiral of great proportions.

CAT’s strengths have always been in its products: high-quality, durable equipment that worked harder and outlasted the competition, by years in many cases. Its dealers are also second to none, the result of decades of careful growth and cultivation, market share gains, and leadership. No one can match CAT for service, and customer loyalty grows with each new generation. But it still lost market share, let competitors gain footholds in markets where CAT had been dominant, and suffered poor margins for nearly two decades.

What went wrong at CAT couldn’t be fixed by dramatic, brute-force decisions; yet the company’s leaders, acting with a sense of urgency and frustration with past problems, made such choices anyway. CAT’s end markets are very cyclical: sales move up and down 20 to 30 percent, not the 2 to 3 percent common in noncyclical markets. That’s just the nature of the business. Excellence in production systems can dampen the swings by controlling everything else other than demand: quality, on-time delivery, safety, and many other metrics that are independent of volume. Robust and disciplined business systems help ensure that. In CAT’s case, the absence of a robust operating system heightened the cyclical swings instead of dampening them—by a material amount, an additional 20 percent volatility stacked onto the already swinging markets. Mistakes made in one direction were ultimately countered with hard pushes in the other, driving increasing pain across the enterprise.

An analogy: Years ago I served in the Peace Corps in West Africa. My job involved visiting very remote villages by motorcycle. One village I visited occasionally was at the end of a three-mile-long stretch of road made of loose sand, with foot-deep ruts all along it from trucks taking villagers to market. There was only one way to go: full speed, to push through the sand, keeping RPMs up, while riding in the high spot between the curving, deeply rutted tracks. As long as I stayed smoothly in the middle, all was fine, but a little swerve to one side would bring me close to falling into one tire track, and a correction to that, closer to the other. Small corrections led to bigger ones, and eventually the front wheel would dig in, the bike would go haywire, and I’d end up buried headfirst in sand and an hour late. Riders who lived there made tiny, micro adjustments smoothly throughout the ride, never overcorrecting and never falling.

CAT: MORE THAN DIRT MOVING

Caterpillar is a heavy equipment manufacturer, founded in 1925. The company makes a wide array of products, including the broadest line of construction equipment in the industry: excavators, graders, scrapers for moving dirt around. It produces large equipment for roadwork, and smaller machines for landscaping and residential construction. Notably, it also has the largest mining equipment division in the world, with massive machines: a CAT 797 mining truck can carry 400 tons of dirt and ore, using a 3,800-horsepower engine that could light up more than a thousand homes.

Aside from machines, CAT makes engines and turbines for heavy jobs around the world. Its diesel and natural gas engines power all kinds of marine vessels, drilling rigs, fracking pumps, and locomotives. They compress natural gas for transmission in pipelines. CAT engines are often the backup power in generator sets for data centers and office buildings. But demand in all these markets can be quite cyclical.

Those cycles got worse starting in the 1980s. A long downturn followed the bursting of a commodities bubble in the 1970s, and there were few reasons to think recovery was anywhere on the horizon. CAT also went through periods of debilitating strikes, which only added to the pressure resulting from weak demand. Coming out of the 1990s, CAT had spent too little on capacity in the face of these challenges. In fact, annual capital expenditures from 1993 to 2003 averaged just about in line with depreciation, meaning spending on factories and equipment was only enough to replace what was wearing out.

Experience has taught many manufacturers that it is hard to foresee the swings up and down in demand, especially in highly cyclical markets. Making cars in the 1950s involved making annual forecasts, estimating demand, and then setting production to meet that expected demand. That meant the factory was going to produce a certain number of cars, no matter what, this day, this month, maybe even this quarter or year. The factory could then plan accordingly so that everything was smooth, with no unpredictable swings up or down in volume. At first glance this makes sense.

The problem is, planning rarely works well. Not with cars, and certainly not with mining trucks. When demand is lower than expected, you’ve just built too many cars, and they are out there sitting in lots somewhere. Eventually production has to be cut, and cut deeper than the level of current demand, to get rid of all the extra unsold inventory. Workers feel the disruption in both boom and bust directions, with disruptive calls for overtime and extra shifts and then hours cut or layoffs, and it hurts. CAT has end markets that swing wider than the market for autos and has experienced this problem repeatedly. Furthermore, the amount of equipment needed to extract desired materials from a mine, or to power huge jobs in remote parts of the world, can vary dramatically over time, further complicating any forecasting.

Take for example the CAT 777 mining truck. In 1990, a truck carrying 100 tons of dirt and rock would have had about 20 ounces of gold ore mixed in. By 2015, that same load might have had only five ounces of gold because of lower ore grades. The good mines were drying up, and the new ones had lower-quality resources. For CAT’s customers, that meant four times as many trucks to get the same gold output. This was also true of copper. And the situation in oil and gas extraction is even more dramatic. A drilling rig that might have used 500 to 1,000 horsepower from the 1950s into the 1990s now needs 5,000 horsepower, with 50,000 more for fracking the well. That’s hundreds of times the CAT power needed to get a barrel of oil out of the ground. The combined change in these factors was far more abrupt than forecasts based on historical ordering levels and fleet replacement could have ever predicted.

Forecasting feels like a science, but it isn’t. To be fair, CAT hasn’t just blindly guessed what the world would look like at any given time. The company has typically used a detailed combination of historical fleet sales, replacement demand estimates, and forward-looking customer demand. As analysts, we do the same thing, and we have been just as wrong as CAT over the years. There are just too many variables and external factors that swing demand, often to extremes.

Another problem is that customers sometimes lie or spin the truth to suit their own needs. During the upturn in commodities, one of CAT’s mining customers infamously told the company it could buy every truck CAT could make for several years. This customer was probably only 10 to 20 percent of CAT’s business; if all the other miners had the same demand, capacity needed to quintuple. As it turned out, it just wasn’t true. The customer was probably ticked off that the trucks it had ordered in prior years hadn’t come fast enough.

Similar bad data came from customers on how many mining trucks were running every day. In 2011 CAT’s mining customers were saying that they ran trucks 24/7, close to 8,000 hours a year. Turns out a lot of them weren’t, and many of those hours that the trucks were running weren’t needed. The trucks were just idling or engaged in some other inefficiency. These challenges contributed to violent swings in an already cyclical business.

THE JIM OWENS ERA: PROTECTING DOWNSIDE WITH A HIGH OPPORTUNITY COST

In 2004 Jim Owens took over as CAT’s CEO. An economist by training, Owens was a bespectacled gray-haired man. He’d spent decades with the company, pushing through supply chain improvements, running successively larger businesses, and eventually serving as CFO. This type of career success is common at CAT, but it can be problematic. The company’s culture is exceptionally insular, and CAT could have used some fresh ideas on production systems back then.

Owens’s message to investors focused on ensuring that CAT could weather the next cyclical downturn, whenever it came. This meant making money instead of losing it when times were tough, an aspiration seeded in the hard-learned lessons of the 1980s. Recessions, poor management, and inflexible labor had driven International Harvester, the largest machinery company in the world, into bankruptcy in that decade. CAT lost $1 million a day for two years in the 1980s.

CAT’s leaders, almost all of whom had 20 to 30 years with the company, still felt the pain from that time. Owens believed that the stock market still paid too much attention to it, and that CAT got too little credit for the company’s hard work making its cost structure more flexible, so subsequent downturns inflicted less damage. That improved flexibility, however, wasn’t exactly due to the systematic improvements we emphasize throughout this book. It came from lower investment and hard-won concessions from the unions via strikebreaking.

By 2004, 15 years of underinvestment had weakened the company. Unlike some companies, CAT did generate enough cash to have invested more, but not enough money flowed to the factories to secure future growth. At that point CAT may have eventually gotten some credit for managing well through recessions, but the leadership team’s cautious approach had missed the fat pitches thrown in many of CAT’s end markets. Market share losses hurt equipment sales in one year, and then they hurt parts and aftermarket sales for the next 15 years that CAT’s machine would have been running. On top of that, without a strong production system to bring discipline, the company mis-executed on the lower volumes it did produce. Quality issues that should have been fixed permanently on the spot were not, which led to delays in deliveries. In the end, while Owens invested more in factory capacity than prior leaders had, it would prove too conservative a response to how the world was developing.

The world was on the cusp of a boom in both commodity and construction markets. CAT excels in mining and oil and gas, delivering big, durable engines to power the work. Drilling rigs can cost tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars a day to run, and the folks running them want tough, reliable equipment. Mining is similar home turf—no one can keep trucks running better than CAT. When copper booms, customers want to fix up every truck they have and buy more to maximize the amount of resources they can take out of the mine. A mining truck carrying 300 tons of dirt and copper is moving $40,000 worth of copper every hour, maybe a million dollars in a day. A $4 million mining truck looks like a small investment when profits are high. On the other hand, it also looks like a high-cost anchor on profits when copper prices are low.

In the early 2000s China was at the inflection point of an amazing run of growth, and its need for iron, coal, and copper to fuel its infrastructure and factory surge was straining the global base of mine production. Copper prices that had been flat for 20 years reached new highs, then doubled, and rose 50 percent again after that. Gold prices reached prior highs as well. The price of metallurgical coal, used to make steel, rose more than five times. These are precisely the sorts of unpredictable compounding factors that can make demand for equipment explode.

The surge in mining demand came alongside not only a rise in oil prices but also a structural shift in how oil was extracted. Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” of wells was becoming far more important than drilling holes. Wells had been fracked for many decades, sometimes with dynamite and once with a 43-kiloton nuclear bomb (1969, in Rulison, Colorado), but widespread horizontal drilling and fracking of wells as a primary strategy was new. Fracking has mostly been confined to North America, but it has provided most of the world’s incremental oil and gas for the past decade, and very quickly it started to displace investments elsewhere.

The power required was massive. By 2008, engines for fracking were roughly as numerous as all the engines in US drilling rigs combined. By 2012, fracking engine horsepower was greater than the collective power used globally in drilling rigs, pipelines, and gas storage and processing, both onshore and offshore.

An official at Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s national oil company, once mentioned to me that a good well drilled in the Ghawar oilfield today might flow 50,000 barrels a day, and a bad one, 10,000 barrels. These simple vertical wells take a 3,000-horsepower drilling rig, make a hole, and oil comes out. A frack site uses dozens of trucks carrying water and sand, and dozens of big diesel engines totaling 50,000 horsepower to force that water and sand down the well hole to fracture the rock containing oil. With all that effort, a typical well might flow 500,000 barrels, maybe a million, across its entire life, which is about what a good well in Saudi Arabia might flow in a couple of weeks.

While fracking requires much more power input to get a barrel of oil out, the cost is partially offset by the relative certainty that oil will flow once fracked. There aren’t many dry holes in well-established fracking regions. Fracking remains the source of most growth in global oil and gas today.

Just as global commodities started to boom under pressure from China in the 2000s, the US construction economy was also seeing a burst of demand. Following the recession of 2001, the US stimulated construction demand with lower interest rates. That fueled a record bubble that would ultimately pop, precipitating the plunge into the Great Recession we’re all familiar with, but not until after a period of significant growth.

At the end of the day, CAT simply hadn’t invested in the capacity to come anywhere near meeting this simultaneous growth in demand in its end markets. Fracking customers bought engines from Cummins instead. CAT’s capacity shortage thus let a competitor into a business where CAT had been the primary, most trusted supplier. More important, CAT hadn’t gained control over the aspects of the business that were within its power, making the situation much worse. Otherwise loyal customers went elsewhere, not just to Cummins in fracking but also to Cummins in power generation sets and to Komatsu in mining.

FAILURE SHOWS ON THE FACTORY FLOOR

I’ve toured countless factories on five continents, over many years, as a part of covering machinery companies. Usually I get to talk to line operators and learn about products, production schedules, and culture. In the Owens era, Caterpillar factories shocked me with their disorganization.

Employee engagement is a key metric of a well-run company. The essence of continuous improvement is collaboration: workers identify hiccups to be smoothed out; engineers consult on how to redesign a part or a process. In modern production, quality is critical, and problems need to be identified, showered with resources, and corrected on the spot so they don’t recur. That’s why any worker can call a stop to the entire production line in auto factories—unthinkable in the 1950s but standard nowadays. CAT’s problems in 2006–2008 included the fact that a great many quality issues were not fixed on the spot: demand was surging, capacity was inadequate to meet it, and the company didn’t want to slow down production to fix problems. Some of the issues were supply chain shortages, where it seemed to make no sense to hold up a bulldozer line while waiting for a hydraulic hose to arrive. Whether because bad blood between management and workers hindered continuous improvement (bitter labor disputes in the 1990s had ended with the union gaining almost nothing) or because CAT was pushing too hard to get product out the door, quality control was broken.

In 2007, I arrived in Peoria, Illinois, for a factory visit that showed just how disorganized production can get when a sharp rise in demand meets a poorly running system. I saw a crowded, inefficient space that, even to an inexpert eye, looked like a problem. Machines were pulled off to the side of the line, waiting for hoses or a touch-up on paint. There were piles of extra inventory at workstations along the production line. And most memorably, there were bins filled with components that should have been on newly made bulldozers and other machines, but instead were labeled “re-work.” At one point those bins were stacked more than head high and obscured the first aid station. The money spent on all this waste limited the funds available to invest in process improvement.

“First-pass quality” is a simple measure of the percentage of time that a product comes out correctly. Most factories have percentages in the high 90s, and 98–99 percent is common (dirty work like casting and forging often scores lower). The first-pass quality numbers on this tour were in the low 80s. CAT was spending huge amounts to fix and rework what should have been done right the first time. Any nonstandard process in a factory, or a company for that matter, is expensive, and doing things a second time is not standard. This and the visual evidence were clear signals: the production process was broken.

With simultaneous surges in construction, oil and gas, powergen, and mining, CAT should have been printing money. But due to these inefficiencies, the demand they did satisfy came at low margins.

Some costs in manufacturing are fixed, so when sales go up, margins should rise materially. “Incremental” margins of 20 to 35 percent on the extra revenue are typical for the construction and mining equipment businesses. Between 2004 and 2006 CAT’s construction and mining equipment sales rose by almost 40 percent, but its margin on selling that equipment went from around 9 percent to only 12 percent, meaning its incremental margin on those extra sales was only about 15 percent. It also likely burned out more than its fair share of employees, with line managers under extreme stress to produce more and faster and overtime hours pushing the limits. This type of imbalance often creates cultural breakdowns. It rewards people who muscle through bad processes to get the job done, not people who stop and fix, as proper Lean management demands. CAT got all that fresh tension in the system for barely any incremental profit. CAT’s response to this was to raise prices to capture some extra margin, risking its long-term competitiveness and market share, because its production system wasn’t working well.

By 2007 the US housing bubble was popping, but CAT machine sales were still growing, up about 10 percent in 2007 and again in 2008. But now profit margins actually went down, with the 2007 margin falling back to 10 percent. Despite extra pricing taken, 2008 margins were worse still, even before the financial collapse—all setting up for a fourth quarter that was nothing short of a disaster.

The failure to profit from surging demand was just one of the consequences of CAT’s underinvestment in a robust production system. Sizable losses in market share constituted another. Just as Caterpillar was struggling with deliveries, Komatsu, the company’s major rival in construction and mining, was smoothly churning out more trucks in its factories. CAT customers faced longer and longer delays, and the desire to get equipment was so strong that even loyal CAT operators switched to Komatsu. They just did not have a choice.

Ironically, Komatsu makes its mining trucks in Peoria, right down the street from what was the global headquarters of Caterpillar. In 2006, CAT was the largest surface mining equipment maker in the world. Its market share has never been officially disclosed, but it was probably about twice as big as Komatsu’s. By 2018, Komatsu’s mining business was bigger than CAT’s.

Komatsu didn’t gain significant share by simply pouring investment dollars into its factory, at least not at first. When we visited its plant in the booming years leading up to 2008, the manager there joked that his nephew started at a junior position with CAT a few streets away, and the kid’s capital budget to fit out his cubicle was higher than the budget he himself had to upgrade the mining truck factory that was beating out CAT. The comment was made in jest, but reality wasn’t much different. Komatsu spent just tens of millions of dollars upgrading equipment in the early part of this boom, not hundreds of millions or billions. Instead, Komatsu used the basics of Lean production: implementing continuous improvement, finding the slowdowns in production, and fixing them. This was two decades after US automakers had a similar moment of panic, with competitors from Japan beating them on quality and production steadiness by using Lean. Komatsu was doing the same to CAT 20 years later.

Finally, as if sagging margins and waning market share weren’t enough, CAT’s conservative posture bled into the strategic realm. The company passed on complementary acquisitions that could have helped meet demand.

Back in Peoria in 2007, I was presenting to a group of Caterpillar employees, who were local Morgan Stanley brokerage clients, when CAT CFO Dave Burritt wandered into the room. I don’t know if he had heard about the event and wanted to see what I was saying to his managers and employees or if he was simply curious. We had a brief chat about press rumors on M&A at the time and potential strategic holes CAT might fill by acquisition. CAT’s mining business had a broad product lineup, but it was too weighted toward mining trucks and bulldozers. Komatsu and other mining equipment manufacturers had shovels as well as trucks, a pretty obvious synergy. The shovel scoops up dirt and dumps it into a truck. Mines are often found in remote places, so there’s a natural advantage to selling parts if you are the largest provider with the most local scale. Designing products together has benefits, too. The shovels that scoop up ore from the ground can be designed to match up efficiently with trucks: four scoops to load a truck is good; four-and-a-half scoops, not so much.

CAT didn’t have a shovel and could have used one at the time. It had developed one internally but had given up on it in the early 2000s, just before the mining boom started up again, not believing the cost was worth it in a mining market that never seemed to recover. Various assets from another machinery company, Terex, were then up for sale, including mining shovels. The strategic fit was quite attractive; yet Burritt’s only comment on my presentation was that assets don’t come cheap, and CAT had no desire to overpay. Instead, CAT rival Bucyrus bought the Terex assets for $1.3 billion in 2009.

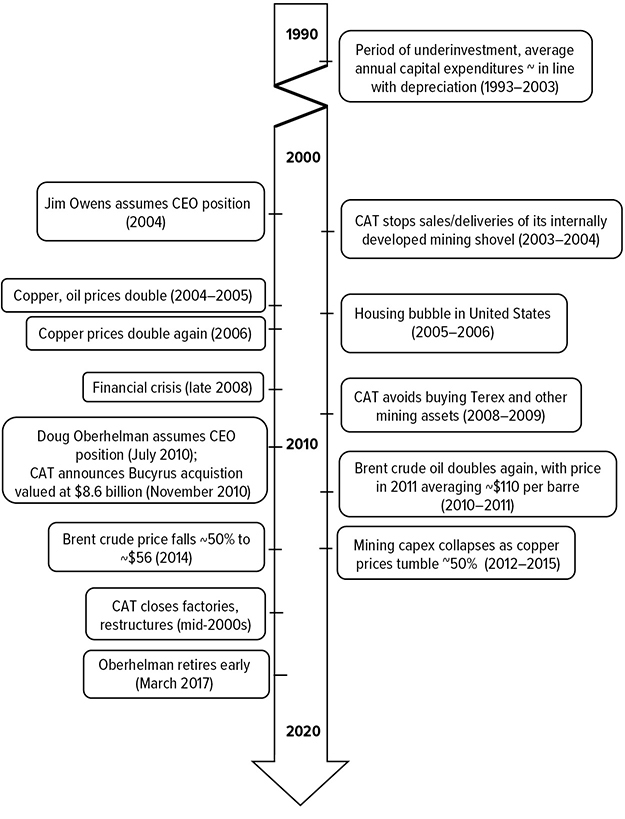

The lesson from the Owens era is that the economist’s approach failed. Forecasting supply and demand levels didn’t work; expecting a continuation of weak demand, CAT lost market share, margin, and strategic position. Its factories were overburdened as it fought to keep up with demand, and quality suffered as a result. The only upside was that the company weathered the 2009 recession fairly well. It gave away a lot of the cycle’s upside, but its downside planning paid off. Coming out of it, Owens, nearing 65, turned over the reins to the next CEO. (See Figure 7.1.)

Figure 7.1: Caterpillar’s volatile history.

Source: Caterpillar filings, Bloomberg, press reports

NEW LEADERSHIP OVERCORRECTS

Doug Oberhelman took over in July 2010. China was still booming, and mining was booming along with it. Oil prices had corrected sharply down for a short while, falling from a peak of almost $140 per barrel down to $40, but by 2010 they were back up over $100. CAT’s sales were rising again, up a remarkable 35 percent in 2010 and then another 44 percent in 2011 to an all-time high, about 20 percent above the pre-crisis record in 2008. However, CAT still hadn’t had time to invest enough in its factories, and it still didn’t have a production system that would allow it to crank out product without more capital.

It had also missed the remarkable rise in the need for construction equipment in China. The country had bought about 30,000 excavators in 2005, over 60,000 in 2006, and more than 160,000 in 2010. In five years, it had gone from a middling market to comprising half the world’s sales, and CAT was nowhere to be seen. Its 8 percent market share in 2006 fell to just 6 percent in 2010. CAT was losing its position as world leader.

Oberhelman had spent the middle 2000s privately fuming as the company ceded market share to competitors. CAT makes decent money selling machines, but selling repair parts for those machines for the next 15 to 20 years is more profitable. Giving up market share hurt long-term as well as near-term profits, and that drove Oberhelman nuts. He had previously run CAT’s engine business, which performed far better than the rest of the company during the ramp-up in the mid-2000s when CAT was struggling to make construction and mining equipment. Parts of the engines business had made the transition to Lean operations, good employee relations, employee engagement, and continuous improvement. Oberhelman had good reason to think the whole company could operate at a higher level.

Right from the start Oberhelman invested in growth. If CAT had captured more of the 2000s boom, perhaps he wouldn’t have pushed so hard to add capacity. If CAT’s production systems had been more well developed, perhaps he wouldn’t have needed to. In hindsight it looks like an overcorrection for sins of the past.

My first meeting with Oberhelman was dramatically different from those with other CAT leaders. He had strong opinions and shared them forcefully, and he didn’t do anything halfway. I arrived with plenty of time to spare that morning (traffic in downtown Peoria is seldom a risk), but my meeting was delayed. There had been storms in the area the night before, and large parts of the town had lost power. While waiting in a conference room, I wondered out loud if Oberhelman had lost power too and was late as a result. The CAT folks around the table chuckled at that idea, and when he came in looking fresh, he commented that his backup power had worked just fine; he was late because he had stopped to help a neighbor with some storm-related issue on the way in. CAT makes diesel engines for backup power, generally a lot bigger than what a house would use. The backup at the Oberhelman house was high quality and could’ve lit up half the neighborhood. Maybe it did. Oberhelman was well prepared, and he loved CAT engines, though he did look sheepish when he mentioned how big his diesel was.

Oberhelman answered questions clearly and passionately, with good reasoning and clear direction. He was a bold and decisive leader, confident and inspiring, and upon taking over as CEO, he tried to fix a lot of things, all at once. He called it being “on a roll and in a hurry.” He made some immediate, important, and lasting improvements in how the company was managed. CAT had long used a structure of group presidents. When we first started following the company, we couldn’t figure out who did what. CAT had group presidents who might oversee global production of bulldozers, for example, but also sales of all equipment in Asia. The org chart crisscrossed all over itself.

Oberhelman reorganized reporting lines to give the group presidents clear responsibilities for the first time. And with these positions came compensation of more than $5 million a year, meant to drive results; many industrial segment heads at other companies made half that. Oberhelman felt that the previous process of managing the company by committee was a criminal waste of talent. He implemented a level of accountability not seen before in a culture that had too little of it—overlapping responsibilities had previously made it hard to find the right throat to choke. One group president told me in 2011 that in 30 years at CAT, he’d never seen a vice president let go. In the first years Oberhelman was in charge, 6 out of about 25 left. With the group presidents having “real jobs” for the first time—clear profit and loss responsibilities—compensation could now be tied to results. That included profit and the cost of the assets used to generate it.

Unfortunately, even with this strong push, CAT’s culture made it hard to refresh the production system sufficiently. There were lots of experts in Lean and supply chain in other industries, but CAT tended to promote from within. Under Oberhelman the company saw an influx of talent from the outside. Small, but unprecedented for CAT.

While those implementing these well-intentioned efforts tried to gain traction, it was clear that Oberhelman didn’t want to miss another boom and lose further market share. The company needed to figure out a way to participate in the up cycle while waiting on systematic improvement. Normal capital budgeting at CAT and other heavy manufacturers operates more on the scale of two years than two months, but Oberhelman accelerated everything. In 2011, just a few months after he took over, Caterpillar’s capital expenditure rose by $1 billion (up 60 percent from the year before and about double the average of the prior 10 years), and another $1 billion in 2012. He sharply increased capacity in China and broader Asia. Some of that capex paid off: CAT’s market share in China, which had fallen steadily in a booming market, improved. And by 2018 its market share in China for excavators had doubled.

Along with organic investments in capacity, Oberhelman took an aggressive stance on acquisitions. He saw it as a mistake that CAT had passed on buying the Terex mining trucks and shovels. CAT’s dealers were clamoring for a broader mining product line, so within four months of taking over, Oberhelman approved a nearly $9 billion purchase of Bucyrus. That was more than six times higher than what Bucyrus paid for the Terex trucks and shovels just a year prior. Bucyrus had other products, to be sure, but they were less strategically attractive, being more specific to coal, and in a few cases in declining markets and product types.

A year after that, CAT bought a Chinese coal mining machinery supplier for about $700 million. Buying a company that made low-value products was an aggressive attempt to get into the huge underground coal mining market in China. As it turned out, the company’s accounting was highly questionable, and the business effectively evaporated after CAT purchased it. That was a spectacular failure, one born of speed rather than prudence and careful diligence. Wasting a few hundred million dollars isn’t the end of the world for a company CAT’s size, but leaders who make serial mistakes can lose the confidence of their employees and shareholders.

Even if CAT had done better due diligence, it was still focused on anticipating demand, rather than on its ability to improve internally. An ideal acquisition process starts with a wide funnel of many opportunities, and the urgency to invest isn’t confined to any one of them. Great companies can see which acquisitions fit best and add value through their unique operations. The reality for CAT isn’t much different, though the opportunity set is less diverse.

Managing the decision to acquire is just as much a systematic process as managing a factory floor, and CAT’s was distorted by its previous failures. The pressure from having underperformed the last mining cycle was strong. CAT’s independent dealers might not have been calling so hard for more product if they had had more wins in the years prior. But they were calling, and in a dramatic pivot from the prior era of caution, Oberhelman answered, short-circuiting the normal process.

If a poorly executed acquisition strategy wasn’t enough, maybe the worst decision Oberhelman made was on inventory. He was intent on getting CAT back into a position of gaining market share, not losing it. Lost sales from inadequate capacity were painful and expensive, and neither the capex surge nor the production improvements being put through could have an immediate result. CAT did the opposite of every lesson of modern manufacturing: it decided to build inventory rather than reduce it. CAT created regional “Product Distribution Centers,” which were basically warehouses for extra inventory, ready to be shipped to dealers and on to customers quickly. To be fair, an increase wasn’t the intent, but it turned out to be the reality.

The inability to fill orders from 2005 to 2008 had made dealers mistrust CAT and its production promises. That had a terrible consequence. It led to double ordering: a dealership might want two machines to sell to its customers, but historically it had only gotten one in a timely manner. So now the dealer orders four, figuring it will get two and will cancel the other orders later if equipment isn’t moving.

In the preceding decades, CAT had widened out its construction product lines materially, adding new machines and model variants, which enhanced the company’s position as the biggest and broadest manufacturer. Without a true Lean manufacturing system, that bigger product line was guaranteed to produce extra inventory or longer waits for machines ordered. So CAT tried to streamline its product line, prioritizing standardized models that would ship quickly, often from the newly established warehouses.

CAT’s warehouses were a Band-Aid fix attempting to address all these issues at once. Dealers could look at the inventory sitting in the regional distribution center and know that if they needed to get a machine, they could. In theory, not only would they stop double ordering; they would reduce their own inventory, relying on the distribution center for quick shipment. Product complexity would be reduced by standard models, and planning for custom orders could be slower and more deliberate.

It takes years (at least five, maybe more) to fix production, and Oberhelman didn’t want to wait. Continuous improvement and employee engagement mean exactly that: little ideas need to be found, implemented, improved, and improved again. That improvement uncovers other processes that can then be optimized. There is no shortcutting the process.

Oberhelman made a bet that demand would be strong with capacity, acquisitions, and inventory build. He then ran into the longest stretch of depressed revenues CAT has ever experienced, including the Great Depression. With too much capacity and too much inventory on top of that, CAT’s bubble imploded.

Mining equipment sales that had grown at a blistering pace from 2008 to 2012 suddenly stopped growing and then collapsed alongside commodities. CAT and its dealers had far too much inventory in a market that fell 80 percent from 2012 to 2015. Mines that had been spending aggressively when copper, gold, and coal prices were high suddenly found they weren’t using their equipment prudently. They had lower cash flows, and instead of buying more or replacing old equipment, they began using the trucks they had more efficiently. And fracking, which in just five years had doubled all the engine power in global oil and gas, also collapsed. Oil prices came down, and frackers figured out how to drill multiple oil and gas wells from the same drilling pad, using a quarter of the equipment.

To top it all off, the recovery in the United States after the 2008–2009 collapse continued to be weak, and construction equipment sales faltered. CAT found itself with too many factories, excess inventory, and busted acquisitions, all made to chase growth that no longer existed. The company under Oberhelman’s leadership reacted a little late, but aggressively, to these developments, closing factories and consolidating production.

After the bubbles had all burst, the last of which was oil and gas in 2014–2016, Oberhelman was forced out early. He had implemented many positive changes, some of which will benefit CAT for decades: instituting greater accountability, welcoming outside expertise, adding new capacity and shuttering old, and reforming compensation systems. One board member, when asked for a postmortem on the former CEO’s tenure, said Oberhelman didn’t know Lean manufacturing from a hole in the wall. He said it with some force and bitterness, and maybe the statement was a little unfair. Oberhelman did know Lean and was putting it in as a part of a production system, along with other positive structural changes. He knew it would take time to gain traction, though, so he decided to make some very large bets on growth in the meantime. CAT’s culture had long rewarded leaders for heroics, not process discipline—these are two very different traits. Oberhelman’s heroic bets failed, and it ended his career.

POSTMORTEM

Caterpillar is thriving today. Its CEO and senior leaders are committed to data-driven, properly incentivized, Lean operations. Results in the mild upturn years of 2017–2019 were among the best of its peers. Safety is dramatically better over the past decade; injury rates that fell 75 percent in the Oberhelman years are down another 50 percent, or a full 90 percent better than the Owens years, when I saw firsthand the chaos in the factories. It took time, but after years of work, the operating system is finally functioning well, thanks in part to some progress in the Owens era and more under Oberhelman. We expect that future volatility will be successfully dampened by the improved operations.

There’s no simple way for Caterpillar to have avoided all this pain, and suggesting so is not the point of this chapter. The company operates in a cyclical industry. Moreover, it was hit with explosive growth when China spurred the global commodities markets early in the 2000s, then a collapse in 2009 nearly as severe as the Great Depression, followed by explosive growth in mining and oil and gas, and then the popping of those two bubbles—all within a 15-year period. That’s a wild ride. As analysts our job is to forecast end markets and earnings, and we got only one of the three huge moves solidly right (the 2008 downturn) and got one terribly wrong—missing the fact that the 2012–2013 peak in mining and oil and gas was actually a bubble. That is the point, though. Forecasting is bound to be wrong and should be done as little as possible. The better path is flexible, rapidly responding, Lean operations.

The problem is that companies are just too tempted to shortcut the process. The hard part about business systems isn’t getting started, nor is it doing kaizens or talking about Lean; the hard part is staying committed. It’s all too easy for a management team to see its time filled with planning, forecasting, and budgeting and then to set systems aside to chase growth when given the chance.

Operational excellence takes tremendous discipline and patience. Either missing out on sales or overproducing or underproducing is unavoidable. It takes a lot of discipline to let that improvement process play out knowing what’s being given up. Most new CEOs we see, particularly in struggling companies, feel pressure to make quick, bold, and impactful changes. It might work, but then again, it might turn ugly.

Much like the sandy road I failed to master in West Africa, learning not to overreact takes a long time, lots of experience, and a system. But it’s the only way to skillfully and consistently handle the booms and busts inherent in cyclical markets.

Lessons from Caterpillar