CHAPTER

12

THE IMPORTANCE OF BUSINESS SYSTEMS AND OTHER KEY LESSONS FROM INDUSTRIALS

![]()

There are real-world dynamics in our case studies. Each company we highlighted was faced with a unique set of problems, and each went down a unique path. Some did it with brilliant success, some with fantastic failure, and some with a mix of each. The data on the successful cases kept pointing us to three common drivers: a relentless discipline on costs, cash flow, and capital deployment.

The companies that rose to the top in our study used their high and growing cash flows to widen the moat within their existing businesses while gravitating investments to higher-return opportunities—and repeated these actions over and over. At that point, the power of compounding takes over and we get on the flywheel. Entire business books have already been written on this topic. But too many companies miss the point. They focus cost-cutting on the easy stuff, quick and abrupt fixes versus more cadenced and sustainable actions. We’ve seen more “one-time” restructurings in our careers than we can count. On the capital deployment side, “game-changing” acquisitions are far more frequent than a more disciplined and repeatable cash reinvestment strategy. These companies don’t get themselves on the flywheel; instead they spin themselves far off it.

The most successful companies emphasize systems and processes over quick fixes, systems that incentivize and drive continuous improvement throughout the organization over an extended period of time. That almost always means being an excellent manufacturer, using tools such as Lean manufacturing. We’ve never come across a company that was bad at manufacturing and still managed to succeed in the long run. Those who manufacture brilliantly can get away with a lot of missteps. Those who do poorly have to rely on top-notch product development with increasingly impossible consistency. Or they have to do a lot of great M&A deals to overshadow the underlying weaknesses. But a slow couple of years or a couple of bad deals, and you’re in trouble.

Operational excellence is absolutely critical to success. In almost every business case we’ve studied, success over the longer term is more often a function of factory floor excellence than of product differentiation. It’s that excellence that drives above-average margins and the related outsized cash generation. Whether that cash is reinvested internally or levered through M&A doesn’t matter, as long as the returns are high enough to stay on the flywheel. But without that cash flow, a company eventually falters, falling further behind peers each and every day. Said a different way, modest product differentiation isn’t considered a game changer by nearly any real customer base. So unless the product differentiation is rather large, manufacturing cost and quality will reign supreme. This was a hard-learned lesson for industrials during their darker era, when globalization began to expose flaws. The ones that failed usually learned this lesson too late.

Lean manufacturing is the most common system on the factory floor. The principles of Lean originated with Henry Ford’s revolutionary Model T assembly line in the early 1900s, but it was honed and popularized by Toyota in the 1980s. At its core, Lean seeks to eliminate waste in the production process. Done right, the result is faster production times to meet hard-to-predict customer demand, lower inventory levels, and higher product quality (fewer defects)—all of which lead to higher cash flow and profit margins. Of course, successful Lean companies get the benefit of free capacity as factory productivity typically improves at some level, often 2 percent per year or more, driving returns on capital higher in proportion to the intensity of the effort. Lean has grown far beyond the factory floor with inspirations throughout the entire organization. Even software developers have their own version.

There are other systems and tools (e.g., Six Sigma for quality control; economic value added, or EVA, for return focus), but none are as time-proven and comprehensive as Lean. The strongest industrial cultures that we have seen are Lean based, and the ones most committed to continuous improvement are Lean based. It’s a tremendous focusing tool with very clear and measurable targets. And publicly available data sets help to continually dial in what exactly best in class looks like, with more than enough consultants out there to get anyone pointed in the right direction.

That doesn’t mean just throwing money into a modernized factory. That can work for a while, but without some serious discipline, it can become a giant money pit and certainly does not differentiate from competitors with similarly deep pockets. Instead it is those with the most productive systems, those who practice continuous improvement and build culture through actions and incentives, that sustain success. Those are the ones we characterize as having factory floor excellence at a differentiated level. These companies are almost always far along the Lean manufacturing journey, and they benchmark internally and externally to best-in-class organizations.

The best of the best go beyond the factory floor. They apply systematic tools to all their functions, including R&D, sales, purchasing, distribution, and back office. Danaher, for example, customized the Toyota Production System and created (or borrowed) more than a dozen tools to focus its employees. Each function has its own toolkit and is empowered to lever that toolkit to its fullest. Increasingly, we see these best-in-class organizations also utilize metrics around employee engagement and turnover. They focus as much on filtering out bad managers as they do on elevating good ones. The same principle holds true for those providing services rather than physical goods, or even software, healthcare, and other high-margin-type offerings. The companies with continuous improvement cultures win out almost every single time. In the short term, “new economy” firms might neglect operations to maximize innovation or the customer base, but we see this as a mistake. The earlier a company can adopt Lean and embed a continuous improvement culture, the greater that company’s odds of long-term success.

And it applies more broadly. We like to use sports analogies because they can have such amazing real-world relevance for businesses—particularly when it comes to studying teams who effectively use systems to help drive a culture of winning and comparing them with those who don’t. Teams often have sharply different budget constraints. In baseball, we see this dynamic with the Yankees and Red Sox versus the Oakland A’s and Tampa Bay Rays, etc.—where massive payroll differences between big-market and small-market teams bracket the top five from the rest (30 total teams). Yet, on average, the team with the sixth highest payroll has won the World Series over the past 25 years, including relative long shots like the Kansas City Royals in 2015 (thirteenth payroll rank) and Florida Marlins in 2003 (twenty-fifth payroll rank). A top-5 spender wins only half the time, driving home the point that big money hardly guarantees championships.

The General Electric chapters bring this exact dynamic to life. GE was on top of the world, winning in nearly every regard, but it eventually took winning for granted and stopped focusing on the little things. GE left its factories to starve, completely losing its cost focus, and had to make increasingly large financial bets to hide its decline. All while Honeywell and Danaher did the opposite and became two of the most respected companies in America. All three had deep pockets, all three could “buy” victories, but one failed famously.

To drive home this point even further, look at one of the toughest manufacturing businesses in America: automotive parts. It is a poster child for hypercompetition and demanding customers. History shows countless failures, and each economic down cycle seems to add more names to the list. But the ones that survived and thrived (the top 10 percent) have done so by investing in fully scaled manufacturing facilities, levering the best in robotics and automation technology. These are typically placed in strategic locations with a great cost base, close proximity to the customer, or both. They implement Lean manufacturing with enthusiasm and consistently benchmark to best-in-class companies well outside the auto world. They work on iterative product enhancements, solving small but important customer problems. They build cost-focused cultures, fully accepting the reality of their stingy customer base. They practice extreme customer service, knowing that it’s hard to differentiate on product alone.

The ones that have remained disciplined have been rewarded with growth and margins well above the average. Their excellence also makes it hard for new entrants to get traction. In fact, their excellence leads to decreased competition, as those who can’t keep up eventually drop out. And with outsized cash generated, these companies are able to remain committed to their factory assets while also allowing capital to find other efficient investments.

The lesson here is that even the worst businesses have examples of successful winners. Just as the best businesses, like software and the internet, have examples of failure. The commonalities are pretty clear, and it’s rarely about having a uniquely disruptive product offering or someone else beating you to that next big thing. Instead, it’s all about doing the little things right, with systems in place to ensure consistent focus, even as leadership changes or business conditions swing.

To get people to actually use a system, companies have needed effective leaders—first to commit the organization as a whole decisively to the system, which means excluding all the other seemingly attractive initiatives that get in the way, and then to promote and demonstrate that system relentlessly. Done right, the result is an organization that goes to work every day knowing what to work on. Done wrong, people learn to game the system, and the organization stops focusing on adding value for customers. The Danaher Business System may be the clearest example of the former. The Honeywell Operating System is another great example. These are world-class business systems that relentlessly focused their employees on adding value for the long term, and they are systems worth studying.

Business systems also help organizations focus on the main tenet of creating value. They focus on a simple question: What does the customer actually value, and how do we supply that at the lowest possible cost? Note that we say what does the customer actually value, not what you want the customer to value. That’s basic stuff, but only half the companies that we have studied live that baseline principle with any real discipline. Voice of the customer is an important tool that is increasingly being adopted by the best companies to drive that very conversation. It’s another way of driving focus—as long as you are actually listening to the customer in the spirit of “two ears, one mouth.”

We’ve talked a lot about business systems in this book, largely because business tools like Lean manufacturing help an organization to find success at the very least on two of the most critical success drivers: costs and cash. But setting up a business system is hard work and takes amazing patience. You can’t just copy the Danaher Business System; the very point of DBS is continuous improvement. Even if someone tried to copy it, it would already be an outdated version. However, the best practices are clear. Keep it simple: find what is critical to your organization’s success, and then measure and compensate around those metrics. The payoff can be big. The flywheel effect itself assures some level of success, and if proper focus is maintained, it can be quite powerful. And whether you are running a company, searching for a better employer, or looking for investments, it’s relevant for each.

DISRUPTION GETS TOO MUCH ATTENTION

There is a common perception that the companies that innovate the best, while getting the “other stuff” (like manufacturing) mostly or somewhat right, are the ones that succeed over time. That statement puts the emphasis on disruption and undermines the importance of manufacturing, marketing and sales, and capital deployment. But the reality is that meaningful disruption is rare and far more difficult to accomplish than perceived. Most companies do it once, providing the foundation for their existence, and then never do it again at anywhere close to the impact of that foundational event. Setting the expectation that an organization hits a home run on every innovation typically leads to no innovation at all.

Take 3M, the Minnesota-based maker of tapes and adhesives. Its most famous innovation was arguably the Post-it Note, a ubiquitous sticky-paper product, the sales of which continue to grow with high and rising profit margins. It was a disruptive product innovation from 40 years ago. But the curse of the Post-it Note is that 3M scientists have spent the better part of the last few decades trying to duplicate its impact. Achieving disruption of this magnitude while predicting future customer needs is extremely difficult, particularly when you consider that the Post-it Note, like many other top innovations, was created largely by accident.

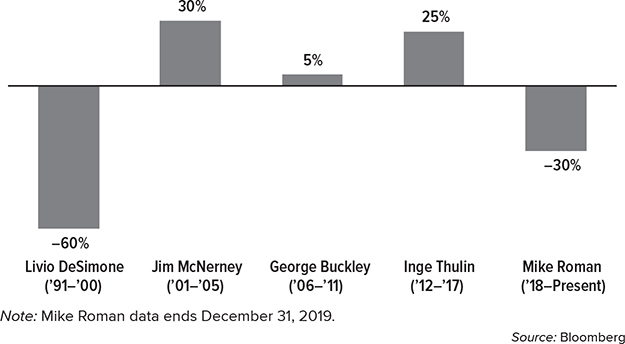

After that celebrated innovation, the company became so focused on the next big thing that it often forgot to do the small things well. 3M is still an excellent company by most measures, but it has gone through meaningful periods underperforming its potential, with growth that hasn’t exceeded that of far less innovative companies and costs that had a tendency to rise well beyond necessity. That said, there have been notable periods of brilliance, with two of the last five CEOs achieving remarkable results. The difference? The two CEOs, Jim McNerney and Inge Thulin, established two very common and simple mandates: the first was a hyperfocus on manufacturing excellence and included holding the line on costs in every part of the organization; the second established accountability for commercial outcomes in the R&D organization. Each of the CEOs made it very clear, via incentives and otherwise, that profit growth mattered more than market share and that developing new products (often incremental improvements on proven platforms) that customers were willing to pay a premium for today was far more important than shooting for the moon tomorrow. Commercial behavior took precedence over disruption.

And the results are clear. Despite representing just 10 of the last 30 years, these two CEOs created nearly all the shareholder outperformance in our study period. (See Figure 12.1.) Both were far more successful than most CEOs of their respective time periods, despite being in some very mature businesses. There is no evidence that any less disruption occurred during these time periods. Scientists who are focused on near-term commercial outcomes seem to be just as likely to stumble upon something big as those whose days are spent dreaming big.

Figure 12.1: 3M stock performed best against the S&P 500 under CEOs Jim McNerney and Inge Thulin, who focused the organization.

The 3M example is more common than not. We use it because the disparate management models of five unique CEOs show such extremes in stock market performance. Sharply rising profits in the McNerney and Thulin eras were rewarded by investors with sharply higher P/E multiples. We could have used dozens of other large companies to make the exact same point, however. Some far worse, in fact. GE under Jeff Immelt was a poster child for this dynamic. Its multibillion-dollar foray into industrial software led it to develop “disruptive” products that customers had no actual need or desire to purchase. Billions of dollars wasted just because the company never bothered to ask, or listen if it did, to what the customer actually wanted. GE was a company absolutely fixated on disruption. Despite a near endless budget and a full decade to make an impact, little of commercial value was accomplished. Good money followed bad, perhaps the most common failing of the Jeff Immelt era.

The reality is that all businesses are founded on some level of disruption, but the vast majority of success comes in the years to follow as products are incrementally improved, manufacturing is dialed in, and markets are broadened or further penetrated. It’s notable that the two most successful companies in industrials over the past two decades, TransDigm and Roper, have no mandate, desire, or effort at all related to disruption. Each has created tremendous value purely by focusing employees on growing the cash flow of the businesses and levering that cash flow by investing in niche, high-return assets.

TALENT MANAGEMENT

Despite all the evidence around process and benchmark-driven organizations, we find that management teams, investors, the press, and the public in general still fixate on “talent.” Especially the personalities, histories, motivations, and strategic visions of the leaders at the top of an organization. But talent, in our experience, is more a buzzword that gets thrown around and misused. That’s not to say that leadership by a few exceptionally talented individuals doesn’t matter. It most certainly does. The truth is, most companies have a barely average subset of both leaders and employees.

Yet almost every executive team to whom we’ve asked a simple question, “What makes your company different?,” responds with “Our people—we have the best people.” But every company can’t have the best people. Someone has to be average; in fact half of the companies by definition have to have below-average talent. It may be even more depressing than that. With so much current-generation talent gravitating toward just a few big technology companies in each global region, what’s left for the rest may be far lower than historical standards. So it’s actually disturbing that many leaders operate with the false belief that their competitive advantage is, in fact, their people. We are not suggesting that a company give up on the goal of acquiring the best people it can find. People are obviously critical to an organization’s success. But there has to be a system behind the people at the top that drives the behavior of all employees, regardless of talent level. Otherwise, the success of the organization ebbs and flows in a rather volatile manner around the turnover or retirement of a small percentage of its talent.

If you look at most winning sports teams, the statistics show an interesting reality. A basketball or hockey team, for example, will typically have a few legitimate stars supported by several solid role players and others that can come off the bench and be somewhat helpful. What you find in the championship teams, however, is talent management at a different level. Stars typically perform as expected. They step up on the big stage. They perform exceptionally well in the big games. That’s not a surprise. The differentiator is the role players. In winning teams, those folks perform better than their salary would otherwise predict, and the players themselves coexist in a system that is amazingly efficient in maximizing each player’s respective skills. They are often led by a coach who keeps everyone focused and distractions at bay, who is willing to make the sometimes unpopular decisions in ridding the team of a “destructive” player, who may have talent but doesn’t fit in the culture or who otherwise brings down the performance of others.

In the business world, driving that similar “win” will require a few stars for sure (let’s say the top 5 percent of head count), but the differentiator of a championship-level performance is similar. Getting average people to perform at a higher level is the key. And we find that “average” may be a pretty fat middle of employees, perhaps 80 percent. The importance of filtering out those who are destructive (the bottom 15 percent is quite possible) cannot be underestimated. And yet we find an unhealthy fixation on the stars and little attention otherwise, which not only makes no practical sense but makes no mathematical sense. Simple math shows that filtering out the destructive talent (15 percent) has three times the impact of protecting the top (5 percent). And getting the fat middle (80 percent) to perform at just a 10 percent more impactful level would have three times the impact of getting the top 5 percent to improve by 50 percent.

Factoring in the challenges in business overall, once the employee head count gets to a certain level and the sexiness of the business itself begins to fade, it becomes statistically even harder to acquire more than a fair share of stars. The interview process itself has shown to be full of all kinds of pitfalls, with many researchers arguing that it’s more of a flip of the coin than most would think. There may be only a handful of exceptions to this rule, and sustainability is questionable. “Hot” companies like Google probably get the pick of the litter in the tech world today, prestigious firms like Goldman Sachs may get a lot of the top folks in finance, and McKinsey likely attracts the best people in consulting. If you are an aerospace engineer, Boeing would seemingly be a pretty darn good place to have a career, but even Boeing has gone from failure to success and back to failure with essentially the same workforce. Once upon a time, Arthur Andersen was the top recruiter of accounting talent in the United States, and it still went down the tubes with Enron in a massive managerial failure.

So do the people overall, and the stars among those folks, really make the difference? Not if they aren’t focused. If they come into work every day and waste their talents, then the entire debate is irrelevant. And if a business depends explicitly on having the best people, it’s probably going to be in trouble longer term. Eventually the industry itself is going to fall out of favor, and all those talented people who came to the business or industry because it was hot will go elsewhere.

In contrast, the most successful companies rely on a system and a group of leaders capable of getting ordinary people to succeed consistently over time while empowering the stars to perform as expected. The risk is that if you lose half your stars because an industry is out of favor or the company is going through a tough time, or you seat that rising star next to a time-sucking dud, or worse, you have her report to a total jerk, then the ratio of bad to good gets even worse. The bad ones never leave on their own. The good ones always have choices. As we noted in the Honeywell chapter, legendary CEO Dave Cote once said to us that he kept his stars by paying them not just for the job they did today, but for the job they would be offered tomorrow. Obviously, companies have to narrow down that small group of truly talented managers, or that strategy gets pretty expensive. But Cote did an amazing job of keeping his top talent on board, getting average folks to step up, and filtering out those who were destructive. The Honeywell Operating System was a big part of that success—perhaps because it exposed ineffective leaders earlier than they would have been exposed otherwise. Cote didn’t make excuses for lousy managers; he simply got rid of them as fast as possible. The data he collected via the operating system were his guide.

When successfully applied, an effective system means that all employees show up to work every day understanding how their role contributes to the value creation engine of the firm, even if it’s only a high-level understanding. This isn’t just knowing how to do their job on a factory floor or in a back office but appreciating how they contribute to the goals of their team, their division, and thus the aggregate enterprise. People gain this understanding only from consistent messaging and from clear, coherent incentives. But a company must also be capable of shaping and shifting the focus and the messaging over time, as the demands of the external environment are not static.

What we’ve found time and time again in the industrial sector is that the most successful companies thrive under a team of well-placed leaders. By “well-placed” we mean those leaders who aren’t the same type across various companies, nor are they the same type throughout a successful company’s life span. They are the leaders who have the appropriate skills for an organization’s needs at the right time.

After all, no leader excels at everything. In this book we celebrate some exceptional CEOs, all of whom also had notable weaknesses. They each delivered exceptional results by maximizing the returns on their particular talents, even if some potential return was lost as a result of their shortcomings.

It’s notable that even great CEOs often begin to struggle as they get past a decade or so into their tenure at the top. Perhaps that is because their strategies don’t cross over into different eras. Or maybe they just get increasingly distracted and struggle to maintain the message and focus. We’ve seen examples of both. The academic world has done studies on CEOs feeling isolated and disconnected and often reporting to boards of directors they characterize as dysfunctional. All these are real signs of burnout, particularly if these CEOs lack the energy or empowerment to drive the change they see as required. In that context, it is worth noting that the worst three years of most CEO tenures seem to be their first year and their last two. The first year they often struggle to get traction with a new message, and the organization gets stuck in a “pause.” The final two years they often seem to be hanging on to the organization by a thread and cease to be effective. We could probably list upward of a hundred examples of this dynamic, including some pretty famous last-inning flops from some pretty talented folks. Even folks we celebrate in this book would have been better served had they exited a year or two before they did.

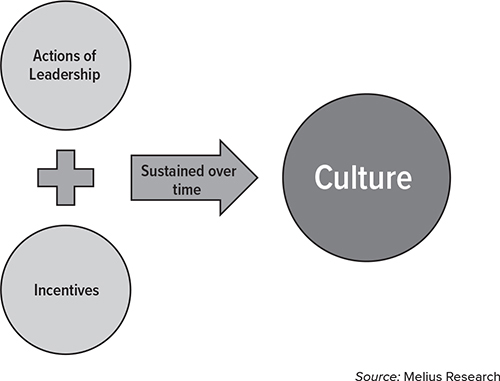

CULTURE IS AN OUTPUT, NOT AN INPUT

Culture is another notion we find many companies fixating on, but they often misunderstand what it represents and how to develop and sustain it. We’ve asked hundreds of executives to comment on their culture, and almost every time the answers were either aspirational (didn’t match current reality) or, worse, made up of feel-good vagaries such as “customer-centric,” “excellence,” “ethical,” or “inclusive”—qualities that are often tough to measure and more often than not do not match up with our observations. Whatever the leaders of these companies were doing, they weren’t seriously promoting a real culture. (See Figure 12.2.)

Figure 12.2: Culture is an output: actions of leadership and incentives drilled into an organization over time.

Culture isn’t something you can force or even actively promote using just words. It’s purely a result of the concrete directions and examples you give to people. It’s usually driven by whatever the leaders focus on, their actions and the incentives set around the organizational deliverables. Leaders can’t impose a culture through just words, but if they embrace a system, use it consistently with their direct reports, and broadcast it to the organization, then eventually you get a culture pretty close to whatever that system encourages. The more consistent the message and the longer the duration of the effort, the stronger the culture. Culture and loyalty tend to go hand in hand. If bad behavior is stamped out and employees feel safe and empowered, that helps to define the very base level of the culture. If performance is fairly rewarded, that helps to define the more positive component of the culture. Both serve to underpin a culture with loyalty as an important by-product. We recently saw a viral post on LinkedIn that relates to this theme. It simply stated, “Millennials don’t leave companies, they leave bad managers.” Not sure who wrote this, but it sure seems accurate. And while culture takes a long time to develop, it can be lost in a nanosecond.

For example, if leaders don’t embrace a clear system, then they’re likely to adopt the flavor of the day. And the distraction of a constantly changing message alone can allow bad managers to flourish. As the struggling CEO of GE, Jeff Immelt described the company differently in nearly every annual report letter he wrote over his long tenure. (See Figure 12.3.) Could the company really change so much over those years, or was he just superficially chasing hot ideas? In the process of fixating on whatever was popular, GE managers, and by extension the employees, lost focus.

Figure 12.3: GE’s annual reports under Jeff Immelt were the poster child for “culture” platitudes.

Part of the problem with the longstanding emphasis on culture is that analysts, journalists, investors, employees, and executives use it as an explanation for successes. But does culture drive performance, or does performance drive the perception of culture? We can’t think of a failed company that at one point didn’t describe its culture in glowing terms. GE and WeWork are good recent examples, with risk taking described as “entrepreneurial.” They used powerful adjectives to make investors and other stakeholders think that their companies had some sort of special powers. But look behind the curtain, and you’ll see that those cultures weren’t much of anything real. It is important that Amazon and Facebook, among others in the tech world, don’t fall into this trap. It is a slippery slope. Just ask Boeing alums; they lived that reality.

CAPITAL ALLOCATION, COMPOUNDING, AND THE NEED FOR REINVENTION

Future investment is essential, in ways people don’t always understand. The key to long-term success is creating a powerful advantage over rivals, which is necessary for survival when the inevitable crisis hits. Whether it’s superior quality in technically complex products, marketing prowess, or advantaged distribution networks, these don’t come right away. Companies have to build a moat with sustained investments in competitively important areas. If done well, those investments should eventually yield ever-higher results. More profits, invested at the higher rate of return generated by the moat, lead to even more profits, and so on—the power of compounding—on the flywheel.

Companies can invest cash internally in operations and new products or externally in acquisitions; it depends on the opportunities available. The key is to generate returns on that investment, translated into cash flow, that show compounding growth in profits. Better yet, companies that master capital deployment (by regularly shifting in search of the highest return: organic growth, acquisitions, dividends, or share repurchases) win lower funding costs as investors pay up for that success and debt rating agencies see better execution. Lower funding costs result in greater compounding, which gives those companies the essential resilience to survive over long periods, particularly important in periods of unexpected disruption like the one we are currently experiencing with this year’s pandemic.

As an illustration, suppose a company boosts revenues at the same rate as GDP, say 3 percent, and is competent at manufacturing. It could raise profits by 5 to 6 percent annually simply with disciplined operating improvements. But if the company consistently allocates the cash to opportunities with a solid return profile, then eventually it should start seeing profits rise by a meaningfully higher rate, say 8 to 9 percent annually. And if the company pursues businesses with a growth rate higher than the GDP, then it can achieve double-digit growth in profits. Double-digit growth is what puts a company well into the top quartile of a wide peer group, typically. A target worth pursuing.

That growth algorithm can prove particularly important in keeping investors interested during times of stock market distress. The spread between stocks that hold value and those that get punished severely becomes even more acute in tough times. And that’s largely a function of the ability to hold profits and cash flow stable when conditions deteriorate. Compounders like Danaher, Roper, and TransDigm, even in their more cyclical pasts, were each able to limit downside during recessionary periods. And while we can’t be certain exactly how they’ll come through this most recent global crisis, we have confidence that they’ll come out better than their peers.

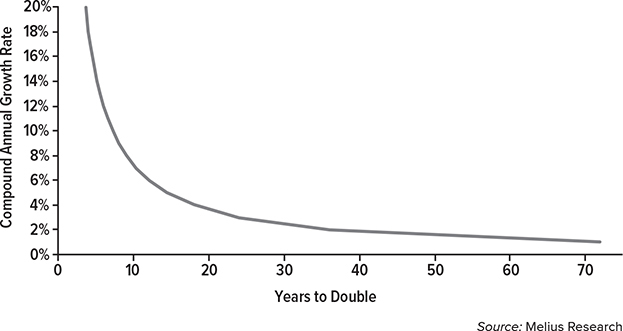

Clearly though, the upside math is most compelling when business conditions are stable. An investment with 10 percent compounding growth, all else being equal, should double in value every 7 years, while one with 5 percent growth would take 14 years. The rewards of compounding growth are enormous, and there are many paths to get there. The main idea is to treat cash as investors do: dispassionately looking for the best return, not what builds an empire. Vanity deals never work. Deals done for defensive reasons are also usually doomed. And “game changing” is normally the path to “game over.”

How can companies achieve compounding? Operational discipline is essential. If every employee and piece of manufacturing equipment improves by even just 1 percent a year, then returns will see an impact. (See Figure 12.4.) And productivity gains of 2 to 3 percent per year are often seen by those with true continuous improvement cultures. Those are the companies that really shine over time.

Figure 12.4: Small deltas in compounding rates make big differences.

Surprisingly, compounding is not explicit in the business model of many firms today. They prefer to work on strategic investments with highly uncertain returns, or they lack the organizational strength to act decisively and shift allocation in meaningful ways. They hide behind the view that “balanced” deployment is best. Balance may make some sense as it relates to risk control. Still, you get there not at any particular moment, but by heavily weighting one area over others when the time is right—such as outsized share repurchases or M&A during periods of stock market or economic weakness, or debt paydown and a tilt toward internal investment when deals are less interesting and valuations are high.

Some companies elect to change the complexion, business model, and collective mindset of the entire organization. We’ve seen companies that were once firmly planted in the industrial world migrated elsewhere. For example, Danaher pivoted from a legacy tools company to a healthcare company through bold spin-offs and opportunistic deals. Honeywell tossed aside its best-known business line, thermostats, to focus on warehouse automation and software. Roper transitioned from pumps to software. But these weren’t pie-in-the-sky transitions. In each case, cash flow was deployed to a higher-growth, higher-margin, more defensible, and higher-return plan, executed over a long enough time period to better manage risks inherent in big change. These examples are less common, but they’re emblematic of the lengths to which the strongest companies will push forward in pursuit of building sustainable competitive advantages.

BENCHMARKING FOR SUCCESS

We find that the most successful companies measure pretty much anything that can be measured but narrow their focus to match up with the goals of the enterprise. They benchmark to compare internal operations. They benchmark to best-in-class peers and to those outside their own industry. They allow humility to reign. There is always someone out there with higher margins, better growth, and a higher market valuation. In continuous improvement cultures, benchmarking can be highly motivational—where it makes sense, of course.

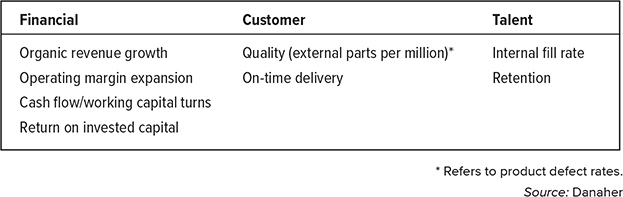

As for specific data that companies utilize, on average we find 8 to 12 fairly common metrics that the most successful fixate on. (See Danaher’s list in Figure 12.5 as a good example.)

Figure 12.5: Danaher has whittled its benchmarking down to eight key metrics.

At the highest level we find cash flow growth and profit growth to form a common base. Most of the best companies add an asset-return metric such as return on invested capital, but that can disincentivize investment and be manipulated, so it has to emphasize earning a return on new investment and allow time for that return to come to fruition. Good investments often take multiple years to really prove out. And ROIC doesn’t necessarily fit at every level within every organization. Plant managers are prone to underinvest, for example, because they rarely stay in that specific role or location long enough to reap the benefits of a modernization project. So there is risk to a one-size-fits-all model. In any event, it’s vital for senior leaders to be held accountable for investment decisions, particularly over the longer term. The best companies seem to have found the right push-pull on metrics, with the awareness that point-in-time targets conflict with continuous improvement and the flywheel. The last thing an organization wants to emphasize is the “sprint to the goal line” behavior that is now so common in business. It’s just not healthy, sustainable, or culturally positive.

Danaher has one of the most focused sets of metrics that we have seen, perfected over many iterations. At its very foundation, Danaher is highly focused on cash flow. Two of the most celebrated CFOs in our studies, at Honeywell and Danaher, offer up cash flow as the single most important metric they fixated on day after day, quarter after quarter. That very focus, they believe, supported the success that their respective entities enjoyed. They both argue that a cash flow–focused firm typically has better risk controls, a sales organization with more price discipline, and a manufacturing organization with little choice but to embrace Lean principles. By contrast, we cite few examples of excellence in firms that focus on market share, particularly for companies well past the disruption stage.

In that context, goals for market share can be dangerous, as they often drive short-term behaviors (sometimes unethical) with long-term risks. Consider BlackBerry, which maximized sales of its handheld units above all else, dedicating its cash and management attention accordingly. Or consider GE: During GE’s entire fall from grace, including near bankruptcy twice in one decade, it was a share gainer. Jeff Immelt cited share gains as proof that the strategy was working, all while the underlying foundation of the company was floundering. And clearly Boeing’s race to beat Airbus and get the 737MAX out the door led to regretful oversights and mistakes.

In some fast-growing, immature industries, market share might make some sense, as when Google, Apple, or Amazon invests in growth to achieve network effects on its platform. But network effects are isolated to a few disparate examples where they can lead to outsized profits down the road. For 99 percent of businesses out there, pricing a contract at or below cost, or allowing a customer to defer cash payments, brings eventual pitfalls. We find few examples where the strategy actually works past a company’s early disruption phase. Some industrials have succeeded with razor/razorblade models that warrant selling up front at just above cost. But these businesses require long-term service revenue streams protected by intellectual property. More and more, the bloom is off that rose. Network effects can prove fleeting, and the US government has threatened to investigate tech firms that have acquired outsized power with this strategy. Countries in Europe and Asia have promised to follow suit.

In the end, every company has its unique circumstances. Different levels of competition, different levels of maturity. But we find no precedent of long-term success for a company that is not highly focused (with incentives) around the cash flows of the business itself. And we find little pushback to the argument that even in the tech world, the top performers are absolute cash flow machines.

The best companies not only measure and compensate based on the most relevant metrics; they do so every single day with “daily management.” A retired Danaher executive once told us, “Even in Danaher’s best-run businesses we had challenges, literally problems that pop up every day.” He went on to say that there wasn’t one single day in his 25-year tenure that he didn’t have to “fix something.” Whether that was an unhappy customer, a supplier issue, a product-quality issue, or an employee doing something stupid, much of a leader’s job is about finding and fixing those problems before they get bad enough to really hurt the company. The earlier he found the problem, the easier the fix. And he thinks that level of daily management is largely what differentiates good management teams from bad. You want a culture where bad news travels fast and leaders can solve issues quickly.

The National Football League offers a relevant study of cultural impacts on success versus failure. The league is littered with teams that win rarely, make the same mistakes year after year, and are forced to change coaches so often that consistency, process, and artful daily management have little time to take effect, even if they are implemented. You would think poor results would catalyze some serious soul-searching, but that hardly happens. Instead, excuses reign supreme, and coaches and players are increasingly paid on a lower set of goals and standards. It’s interesting to note that the bottom half of NFL teams pay their quarterbacks about the same as the top half. Coaching staffs aren’t paid materially differently either. Losing teams just set lower standards and define their journeys in terms of “progress” as opposed to wins and losses. They project an image that a system exists and that fans should be more patient, but over time it becomes clear that it’s just not true. The virtual equivalent can be seen from factory managers (and their CEOs) in winning versus losing operations. There may in fact be progress, but the pace is too slow to close the gap with winning cultures and teams. Continuous improvement cultures raise an already high benchmark. Winning cultures tend to have amazingly honest conversations about success and how that will be measured, and about humility and how that tends to sustain the already high level of achievement.

The good news is that sports or business death is never all that sudden. The Honeywell case study is a perfect example of a company that got back on track after being on the path to likely failure. And although not illustrated in this book, Ingersoll-Rand, ITT, and Illinois Tool Works were each successfully managed out of the doldrums. 3M was struggling under a new CEO but became refocused during the pandemic and has risen to the occasion. It is very possible to turn around losing franchises, but it takes a healthy dose of humility and a period of relentless refocus.

RISK MANAGEMENT

Most corporate leaders are comfortable focusing on growth and profitability. That’s what Wall Street uses to value companies and what the compensation for those leaders is normally geared toward. There are nuances in how to define those metrics, like cash flow versus profits or margins versus returns on capital. But in the end, compensation schemes need to be tailored to the challenges of that particular entity. Differentiation is often less dynamic than you would expect. Where we find few best practices, however, is around risk management and risk control. Leaders are often free to pursue strategies that offer sharply different risk profiles overall.

Ironically, professional investors tend to understand risk better than many of the management teams of the companies they invest in. Professional investors tend to have a “maximize gain while minimizing loss” mindset that identifies potential risks and expects to be compensated for them. This is a fundamental value driver that underpins the structure of almost everything in the finance world, and it’s perhaps easiest to observe in bond ratings, where risk levels are assessed and assigned before securities are even sold. It’s directly seen in stock valuations when you compare more predictable revenue models, like software, with less predictable ones, like financial services. There’s a similar dynamic when you compare cyclical assets with less cyclical. The valuation differences relate completely to risk perceptions.

Inside many companies, especially once you get a few layers down into the organization, there’s little such appreciation for risk. And incentive compensation systems often ignore risk entirely. Even in some otherwise well-managed firms, people are paid to boost revenues and earnings or to maximize cash flows, but these people aren’t guided on how much risk to take when doing so. The result is a tendency toward risky decisions, especially when the potential consequences of those risks are well in the future and therefore another leader’s responsibility.

To achieve growth and profits, both of which are outputs, businesses must contribute various inputs, and not all inputs are created equal. Some come with contingent costs, and others have timing consequences that skew evaluations of costs and benefits. In our experience, the most successful companies are consistently mindful of the inputs that best drive their desired outputs, and they find ways to limit the use of risky inputs. The outcome of this mindfulness is higher-quality growth, or returns that are less volatile and more sustainable over the long term.

Risk management is therefore a critical variable in our long-term analysis of success versus failure. And although investors are pretty good at discounting different risk profiles, companies are often very much asleep at the wheel. GE’s near failure twice in one decade relates specifically to its failure to manage risks on more levels than we can even count: project risk, M&A risk, high debt levels, pension funding risks, cultural degradation risk, underinvestment risk, and the actuarial risk it retained with long-term-care insurance liabilities. Nearly every failure that we can identify has some element of an altered risk profile that went very badly, whether an ill-conceived M&A deal, or poorly made investments, or bad leadership allowed to linger far longer than warranted. Management flaws relating to risk control begin to show even in good economies but become particularly pronounced in recessions. (See Figure 12.6.)

Figure 12.6: Returns are compounded by executing the flywheel.

CONCLUSION

All the companies we study have processes of some kind; that’s not what’s lacking. But much of that time gets spent on unproductive activities, such as budgeting, forecasting, doing capital planning, and fixing problems that were allowed to linger and grow. What works, instead, is an intense focus on three goals: containing cost—by reducing waste at every step; manufacturing for repeatable quality; and driving a high level of customer intimacy throughout an organization. It works when these are the goals of everyone at the company, and continuous improvement as a mindset becomes central to the culture. At a bare minimum, the companies that effectively employ continuous improvement will gain opportunities through higher cash flow that could be spent on growth.

The best companies are those that have gone a step further and built something different and new, growth companies that are created around operational competence rather than around a product cycle. Danaher and Fortive operate a wide range of businesses arguably better than anyone else in the world, from professional tools to biotech. Roper transitioned from managing industrial assets to software. TransDigm is specialized, but with its tremendous focus on protected niches, it vastly outperforms even other well-managed aerospace suppliers. While it’s not immune to today’s aerospace woes, its track record of managing through challenges is well established. Manufacturing a quality product that customers demand matters, of course, but what really differentiates is the repeatability of processes, business systems that maximize effort and focus in every function. The flywheel of success comes when operations generate cash, which is used to invest in more assets, which are then improved.

Lessons on what to avoid are clear. Forecasting end markets many years out is a mistake in driving strategic decisions; it’s a well-informed coin flip. GE bet heavily on years of uninterrupted growth in oil and gas industry spending and on spending for fossil fuel–powered electricity generation. Caterpillar believed spending in mining would grow exceptionally and for some time—and now US coal is in a steep spiral down to nothing. GE sold off NBC to make those ill-fated investments just before the media business improved. GE and Caterpillar are extreme examples, but outthinking end markets on growth 5 to 10 years out is a loser’s game. To that point, no one could have anticipated either the timing or depth of destruction from the current pandemic. And if forecasting the top line is a remarkable challenge, then forecasting future profitability is even more so. It is a rare management team that would suggest margins will get worse due to market dynamics or their actions. Optimism is universal.

Management plays a critical role in setting goals for an organization and in reinforcing behaviors that support those goals. Incentives matter more than most managers think, and those incentives need to be tuned to the current strategy. The departure of a long-term CEO is an uncertain moment in a company’s life, doubly so if the CEO is a legend, like Jack Welch at GE or George David at United Technologies. Investors often tread cautiously during such times, fearful of earnings “big baths” when hidden problems from the prior leadership are surfaced. The bigger danger is that things don’t change. A strategy that’s run its course, as at United Technologies, needs a careful reevaluation at the CEO and board level. United Technologies was one example, but there are a great many others. Managers who rise through the ranks during the 15-year run by a top CEO are going to be naturally supportive of the older strategy, and they probably have too much hesitation to break out of it. They’ve spent their careers implementing it, after all. That’s one of the most impressive results of Dave Cote’s long run of success at Honeywell; he chose a successor in Darius Adamczyk who took the company in a far different and yet still a positive direction.

The right questions definitely exist, for employees exploring their careers and for investors exploring ownership stakes. Management matters, often more than the business itself, over anything other than a short time frame.

We increasingly look for two markers of success. One is humility, a shorthand way of saying the ability to embrace feedback and change, benchmarking, and a method for generating quality feedback. The other is a well-established process for feedback, which enables continuous improvement, the core of any successful industrial, though one too often trapped on the factory floor rather than spread throughout the organization. Red flags are the opposite: arrogance, overconfidence, and a strategy of managing tightly to targets, as well as strong bets on end markets, or at least high confidence in making them. Shooting from the hip is dangerous in itself and probably a marker of something missing in its place.

Business books talk about strong leadership, but that often gets placed into military parallels, where larger-than-life, loud men shout out commands. That never seems to work in business. We define “strong” as the ability to plot a reasonable course, communicate the plan, and put people in place who can execute, all while incentivizing and rewarding behaviors that move an organization steadily toward long-term targets, with a continuous improvement mindset.

The best companies have strong cultures, but only as the output of years of sensible actions, disciplined processes, and incentives set by leadership. Every employee knows the mission and works toward some facet of it every day. It’s a fairly obvious trait when you get to know it.

What does all this mean for the new economy? As industries age and competition deepens, newer companies that lack operational discipline will fall, just as hundreds of old economy leaders have done. Feedback loops and continual improvement work in any industry but seem to be lacking in much of the newer tech world. Big-idea cultures without daily management tools eventually go off the rails. Concept businesses and software companies are particularly prone to those risks.

Management of hard assets within the framework of an IP-based company is extra tricky; Uber and WeWork are good examples. Often the strategy seems to be to pretend the assets don’t have a cost, so everything will work out over time. Sometimes the tech economy’s crossover into physical assets seems an exercise in pushing as much pain outside the system as can be borne, rather than minimizing costs. That works only so long as there are enough desperate people to take the work, and it leaves itself vulnerable to an actual, profitable business. This is in addition to the clear ethical implications and likelihood that government watchdogs will take notice.

The lessons are not complex in theory: measure, develop process, apply incentives, correct as needed, and repeat. The further along that journey gets, the more robust and differentiated it becomes. The moat widens; the culture becomes ingrained.

It’s critically important that an organization focus on the little stuff that keeps it on the flywheel. Adopt a business system that focuses the effort. Benchmark externally and to best-in-class organizations. Encourage a humble culture based on continuous improvement. And promote leadership that understands the critical importance of managing costs, generating increasingly higher cash, and redeploying that cash toward the highest returns. Not difficult at all, but somehow it gets lost with each generation of new companies that are so focused on near-term success, they forget that “long term” is often right around the corner.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The themes we’ve discussed in this chapter are the most notable of the best practices we have observed over time. But an exhaustive list would be misleading anyway. There is more art, and perhaps a bit more luck, to business success than we would like to admit. A commonality of most of our case studies is a lack of real-time popular appeal. Many readers, for example, have never heard of United Rentals; yet it has built up a business that could be called the Uber of construction equipment—but arguably with a much more sustainable business model than Uber’s.

This is partially why we think the case studies are so valuable. They are off the radar screen but shouldn’t be. Each case offers clear and common business problems and a set of solutions that either worked brilliantly or failed miserably. And while there are commonalities, there are also a lot of nuances and finesse. Without the context of the studies, the lessons we discuss here all fall pretty flat.

One thing we can guarantee is that beyond today’s infatuation with disruption, these same challenges will emerge again. Many are happening already. WeWork needed emergency funding just a month after nearly landing on a windfall of an IPO. Facebook has been on Capitol Hill answering to legislators with increasing skepticism. Apple and Google are both facing challenges of operating in a global economy, where the rules are often different and the playing field hardly fair. And there is broad distrust of this new generation of success. Tech billionaires rank down with used car salesmen as related to public trust, and those perceptions will impact government policy for a generation.

Industrials have seen this movie already. We could have changed the names above and gone back 20, 40, even 60 years and made the same statements. In nearly every case, there is an industrial company that either solved for one of these problems or failed trying. Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it. We don’t have all the answers. Far from it. But we do have some, and those answers have implications for a broad audience: for those who invest, those who lead, those who still seek a career, and those who regulate—there is plenty to go around.