CHAPTER

2

GENERAL ELECTRIC

PART II

How a Culture of Arrogance Led to the Largest Collapse in American History

![]()

The GE CEO selection process has historically been a grueling multiyear contest pitting business heads against each other in a rather public forum. Welch had delayed his retirement while the Honeywell deal was being reviewed, so the contest to select his successor was particularly intense and long. In hindsight, it may have led to a level of fatigue and burnout that post-Welch management seemed to exhibit at GE.

In any event, a few days before the tragedies of 9/11, Welch hit mandatory retirement and turned over the reins to his chosen successor, Jeffrey Immelt. His parting advice, as Immelt told me some time later, was to “blow it up,” which we assume was Welch’s way of giving him the green light to chart a new and quite different path. That’s essentially what Welch had done when he had taken over in 1981. And by 2001, GE certainly needed a reset.

For one, the market’s expectations were out of whack. Profits had ballooned in the late 1990s due to GE Capital’s investment winnings, outsized pension investment gains in the bull market, and a bubble in gas power generation. In 2000, the company had an eye-popping P/E ratio (price to earnings ratio) of 40x, more than double the market’s average over time (at 17x in early 2020). And if you adjusted out the unsustainable part of the earnings algorithm (i.e., pension and one-time gains), that ratio was likely closer to 60x—insanely expensive for a mature company. The GE that Welch had created was not sustainable, and with the stock market falling back to earth, Immelt needed to take the up-front hit. (See Figure 2.1.)

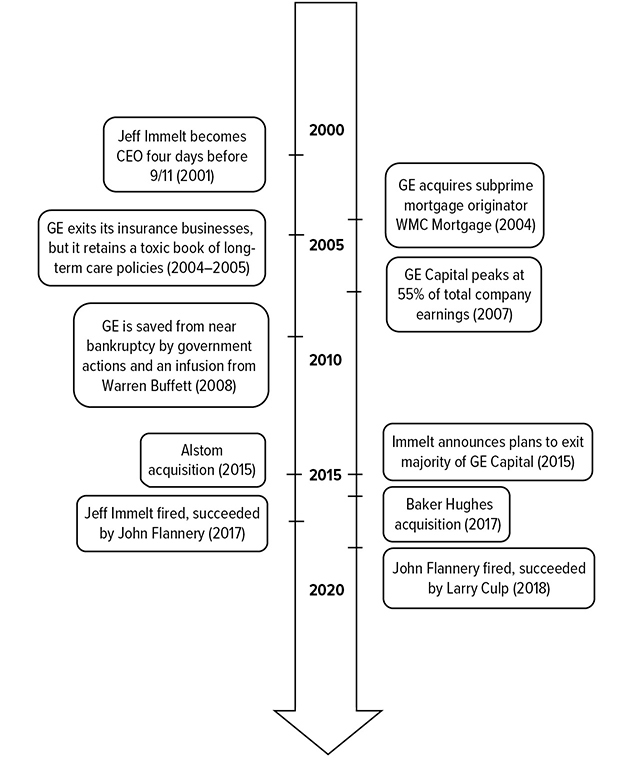

Figure 2.1: The Jeff Immelt era and beyond (2001–2019).

Source: General Electric filings, press reports

More specifically, GE Capital needed to shrink, or at least decrease risk with lower debt leverage. Unlike the industrial businesses with technological and scale superiority, GE Capital had few sustainable advantages other than low-cost borrowing. The supernormal profits were attracting powerful rivals, and regulators were increasingly loosening the reins on banks, allowing them to expand into these niche areas.

At the same time, while Welch had invested heavily in his factory assets through the mid-1990s, they began to fall behind by the time Immelt took over and needed a fresh round of investment. After his initial successes in engines and turbines, Welch had not pushed forward with next-generation technology, and R&D had not kept pace. This is likely the result of the hyperpressure he had put on his managers to beat their quarterly targets. Welch’s infatuation with earnings beats, his rising P/E ratio, and also the stock price in his later years was notable, even by the crazy standard set in the days of the tech bubble. As a result, shortcuts were taken and the GE core was beginning to rot.

In hindsight, Immelt should have immediately dampened expectations. He even had a ready excuse: the horrors of 9/11 hit a week into his tenure, sparking fears of recession and a cutback in air travel. GE had provided the engines on the jets that hit the World Trade Center, leased the aircraft, and insured both buildings. Freed from Wall Street pressures, he could have slimmed down Capital and done the hard work of forging a new path. But he did neither.

GE Capital did sell some assets early on, but it bought far more. It was expansion that began to border on reckless, but few cared to notice. By then, investors were caught up in the housing-driven boom of the mid-2000s.

Still, Immelt was a hard-nosed executive who had risen to the top of a no-nonsense company. For him to get caught up in the company’s past successes shows how hard it is for any prosperous company to make the transition to a new market context. If we justly praise Welch for transforming a company that was still profitable, then we can’t so easily expect Immelt to “blow up” the most admired company around. Eventually Immelt did make fairly drastic changes to GE, although usually too late.

More interesting than what Immelt kept is what he changed. Where Welch, trained in engineering, had focused on operational details and gotten into the weeds at plants, Immelt was from sales and had little interest in factories. He had a more affable, positive manner and spent more time on people than process. He wasn’t interested in systems. Immelt used to claim that he knew his top 600 executives in some level of detail. But factory visits became less common, and business reviews lacked the intensity of the Welch era. GE was becoming a much softer company. Some of that was needed in a world that was also softening, but the pendulum swung too far, and the culture began to have conflict. Welch-era managers were taught accountability, and results were the scorecard. Newer managers focused on big ideas. Most were caught in the middle and struggled to know what to focus on. Immelt also seemed caught between two conflicting worlds.

Immelt saw GE’s size and influence as bigger than just an average company—he saw the political power, the influence on policy and trade, and the impact his words could have on a world far wider than GE’s reach. By 2002 his power was perhaps beyond compare in American business today. And that type of power invites all kinds of challenges—arrogance for one, but outsized demands on your time for another. Pretty easy to lose focus with that context. Something the CEO of a complex company can ill afford.

As for the outsized power, that wasn’t so crazy back then. The largest corporate CEOs were celebrities, household names with reputations fed by their broad media appeal. And GE was top of that list. GE had a factory or sales office in nearly every major congressional district in the country. It was one of America’s largest exporters, an important military supplier, and one of the biggest unionized employers. Its products kept the electricity on in people’s homes, powered aircraft, presented the news via NBC, and ran diagnostic testing in most American hospitals. The lending arm touched nearly everyone who had a store-branded credit card, which was most households at the time. The world now has Google, Apple, and Amazon to look up to, but GE was equivalent to a combination of all three. When my boss at Morgan Stanley asked me in 2001 if I’d like to take over responsibility for analyst coverage of GE, I could hardly control my excitement. It was a massive promotion and a career-changing event.

The early Immelt days did show promise, and having trained under Welch, Immelt tried to continue his predecessor’s disciplined accountability while pushing his big-ideas agenda. But over time Immelt’s softer edges defined the culture. No more mandatory firing of the bottom 10 percent or “Fix it, close it, or sell it.” Instead of bold up-front bets that went against the grain, Immelt took the long view on conventional ideas. Welch had pushed R&D to develop products within its core, products that could be commercialized within five years. Immelt had a wider lens and favored scientists with big visions, even if those technologies were 20+ years away from commercialization. Welch wanted no-nonsense, practical people, while Immelt sought optimistic dreamers. In fact, Immelt’s entire legacy could be summed up in one word: “optimism.” Ironically, that would become his downfall.

GE MANAGES THE NARRATIVE AND EARNINGS TO HIDE ITS FLAWS

Enthralled by the future, Immelt didn’t want short-term problems or criticisms to get in the way, and so he doubled down on an unfortunate legacy of Welch: earnings management. In the late 1980s, as GE Capital began its expansion, Welch had discovered that financial services offered a lot of discretion in declaring gains and losses. When GE’s core businesses had slow quarters, he could balance them out with strong results from Capital and vice versa. Welch’s earnings management became famous, even applauded, despite the clear ethical lapses guaranteed to occur with such discretion. Immelt continued and possibly even expanded the practice. After multiple years of crisis that have now defined his legacy, this earnings management arguably crossed well into the unethical.

To win at this earnings game, GE cut back on disclosures—details that analysts relied on in order to navigate this increasingly complex company. At Morgan Stanley, we struggled to find any consistent way to model out the company’s earnings or even compare its risk profile with others. The reported numbers were constantly changing, and it took multiple days or weeks just to reconcile the differences, if you could at all. And just when you felt like you were looking at solid financial comparisons, the company would alter its disclosure, and we would have to start all over again.

Money seemed to pass back and forth within GE businesses, for no clear reason special-purpose entities were created, and loans were originated and then syndicated, only to fall off the balance sheet, all while creating some sort of paper profit gain. Complex derivative products were used. Long-term debt was swapped for short-term, fixed-rate debt for floating and vice versa. Currencies were bought and sold, all in the name of “hedging,” but there seemed to be no consistency if that was the case. Special leasing arrangements were sometimes used so that even shipping a unit across the street would constitute a sale and revenue booked. Tax gains and losses were created when needed to smooth results. GE would fight the IRS on every penny. Most quarters saw some sort of “tax gain,” and that gain was buried in a financial statement category called “other.”

It was beyond complex. It was financial engineering at its most extreme—perhaps on a scale never seen before and not since. And there was no one outside the walls of corporate HQ that had any ability to follow all the pieces. Those of us who followed the company for a living were just kidding ourselves that we understood all the financials.

The difficulty we had in modeling out GE wasn’t for a lack of talent or resources. We had some of the most qualified finance experts on the planet, used to tearing apart financial statements for sport. But we couldn’t make the models work. And we were far from alone. Debt rating experts seemed particularly frustrated. The SEC should have taken notice, but no one seemed willing to take on GE and its powerful lobby.

In today’s world, analyst complaints get the attention of auditors and regulators. We saw that in the failed WeWork IPO in late 2019. The system worked to protect investors from misleading financials. But back then, no one was empowered to call out GE’s actions. The power in the system was all in the possession of large companies, which had a hand in setting regulations and then abusing them, and any vocal complainants were usually dealt with harshly.

Adding to the difficulty, Immelt reinforced Welch’s “Don’t question us” mentality. While we celebrate many of Welch’s accomplishments, the darker reality included the fact that Welch had built a fortress around GE. Outsiders were viewed with disdain. The arrogance and insularity grew with Welch’s public celebrity. The intimidation factor was massive. And though Immelt softened Welch’s harder line on outside criticism, he largely looked the other way when subordinates carried on the practice. At GE, protecting Immelt’s image and the company itself became more important than any ethical consideration.

As a GE analyst, I knew that the power of GE put my job at constant risk. If the company blacklisted me, I might never find work again. GE’s talented, relentless investor relations (IR) team had no interest in letting analysts challenge its public narrative. The scare tactics had few boundaries.

In 2003, I gave the company the courtesy of seeing a draft of a report I wrote that criticized parts of GE Capital and compared its rising risk profile directly with that of banks, notably Citigroup. Sending drafts was a common practice back then to speed up fact-checking. Shortly thereafter, on a summer Sunday afternoon, I got a call on my cell phone. It was a member of GE’s IR team. The substance of the call was a demand that I drop the report altogether. If not, the team would use all its power to squash my credibility, including leveraging CNBC anchors (GE owned CNBC within its NBC unit) to attack my findings. The caller also raised the possibility that GE management would elevate its dissatisfaction with me all the way to the top of Morgan Stanley’s executive team. I was reminded in that call that Immelt knew all the bank CEOs, having most on speed dial.

Morgan Stanley, to its credit, allowed publication, but only after I had a lengthy back-and-forth over multiple days with internal lawyers and managers, who softened the findings in the report. One of the quieter ways that GE would go after an analyst’s credibility would be to question the relevance of the findings and question the quality. If you’re managing an equity research department on Wall Street, it’s hard to know what action to take when a company calls and says the report quality is low and misrepresents the truth. The “truth” often takes substantial time to surface, and relevance is highly subjective. It’s usually just safer to soften the report and move on, which is exactly what GE wanted and almost always achieved.

GE’s threats always included some comment about the company’s relationship with the firm’s investment bankers. After all, for investment bankers, GE’s size, debt issuance, and dealmaking made it a virtual ATM machine. An analyst could only get in the way of a never-ending stream of revenues. In fact, for the better part of my first year covering the company, one investment banker called me nearly every day to remind me that GE had the power to destroy me, and if it was up to him, he would advocate for exactly that. In those days, that level of harassment was still allowed, and research had limited power in the organization.

I tried to shake it off, but GE’s tactics certainly affected my work. It’s hard to stay firm when punched in the face so frequently and violently. At some point you start to give in. By 2004, I upgraded GE stock to a buy rating on a view that margins were set to inflect upward. That served to lessen the harassment for sure. I even got a holiday card from Immelt that said, “I have 19 percent op rate [operating margins] tattooed on my ass.” That margin never happened, and the stock call was dead wrong.

Several journalists at major financial publications have shared with me similar stories of GE’s pressure over the years. This was particularly true of the Wall Street Journal, which always put top talent on the GE beat, usually the kind of reporters that GE did not want—the kind that asked a lot of questions. Over time, I bonded with some of these folks, mostly over GE’s severe reactions to anything we would write that wasn’t outright complimentary. Legendary Fortune magazine reporter Geoff Colvin told me of his astonishment at GE’s violent response to a critical report that he wrote on Immelt. He said that GE’s response was the most aggressive that he had ever experienced in his very long career in journalism.

All of this ties back to the celebrity status that Welch passed down to his successor. As we know from Welch’s divorce proceedings in 2002, even in his retirement, he enjoyed outrageous perks like continued access to GE’s oversized fleet of aircraft. Immelt, for his part, embraced the perks with similar enthusiasm. The airplane fiasco reported by the Wall Street Journal in 2017, where a backup jet followed him on business trips in case the main jet had problems, exposed just a small piece of the excess. In selling NBC in 2009, for example, he had an entire golf course shut down so he and Brian Roberts of Comcast could negotiate in private while playing. Roberts viewed that as highly unnecessary. Even among large and powerful companies, these types of behaviors are outside the norm.

Immelt despised spending time with analysts and shareholders, a group that he believed lacked the imagination needed to understand his big ideas. He even joked about that part of his job being the least pleasant. Any effort to do so was in the context of “keeping enemies close.” In fact, on one particular occasion, he invited me to be a guest of his at the annual College Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony, an organization that he was president of at the time. Sometime before dinner he introduced me to the head of the NCAA, Mark Emmert, as “the most dangerous man on Wall Street.” A joke perhaps, but the tone bordered on malicious, and when I laughed, he only glared back, then walked away. It was clear that he feared anyone who could derail his vision, despite the fact that analysts’ influence at that time was at a low point, and GE was still a giant, powerful organization. Was he that paranoid, that insecure, or just plain afraid that stakeholders would begin to see that GE was faltering and that he had lost control?

In his earlier days on the job, he was considerably more “Street friendly,” and I got a chance to spend time with him in Dallas in 2003. I hosted a meeting where he was invited to speak with a couple hundred of Morgan Stanley’s individual investor clients and afterward to sit down more privately with about a dozen local institutional investors. Even though I had set up both meetings, GE told me I could not sit in on the more private one—the company would not risk having Immelt’s informal conversations seen in print.

Before the meeting we had a brief chat in the hallway, and I asked about his life as CEO. “Do you wait in line at the hotel check-in?”

“No, my forward team handles it and hands me a key when I walk in.”

“Do you use the hotel gym?”

“No, my forward team flies my fitness equipment down and sets it up in my room.”

I covered other large companies. None of their CEOs at that time had a security detail, advance teams, or gym equipment set up for them in their hotel suite. As a more experienced analyst today, if I were to hear that, it would set off all kinds of alarms. Back then, as a newer analyst, I just figured it was justified by GE’s size, and no expense was too high to make its CEO comfortable.

It’s easy to understand how Welch’s success went to his head, but Immelt hadn’t yet created an ounce of value at GE. The stock had long since stopped its ascension, and the company’s credibility was beginning to slide.

Admittedly, the early years after the euphoria of the tech bubble along with GE’s outsized reputation would have been a tough situation for any leader, but Immelt didn’t rise to the occasion. Instead of Welch’s bold, savvy bets, which were financed with the strong cash flow that came from patient attention to costs and productivity, he became fascinated with the hottest new trends, financed largely with debt. After the dark days of 9/11, he went into airport security, but he had no strategy for developing a competitive advantage. He paid a hefty price to acquire a number of subscale security firms that had no real connection to each other, only later to be sold at a big discount and loss to United Technologies. Then he made a play in clean water, but the myriad of acquired assets never quite fit together and were likewise sold at a big loss. This pattern went on and on for the better part of 15 years. Overpay for hot properties that fit the big-ideas concept, capitulate a few years later at a loss, and shrug it all off because GE’s size made losses appear small and they could be covered up by gains elsewhere.

His poor timing was almost surreal. In 2007, after arguably the greatest real estate bull market of all time, he went heavily into commercial properties. He also bought a subprime mortgage originator near the housing peak, despite GE having exited a similar business years earlier and despite clear signs of ethical challenges within the industry overall.

Far from improving the acquired businesses with GE’s vaunted managerial skills, the company usually made the asset worse. The high prices paid for each acquisition left little to reinvest in the business. And when Welch left, so did much of the factory-level talent that got GE to the top in the first place. Six Sigma was long forgotten, Lean manufacturing a mere brief experiment. Benchmarking against traditional metrics fell off the list and was replaced by a new concept called Net Promoter Score, another flavor-of-the-day hot new metric. All the while, the company’s manufacturing quality slipped.

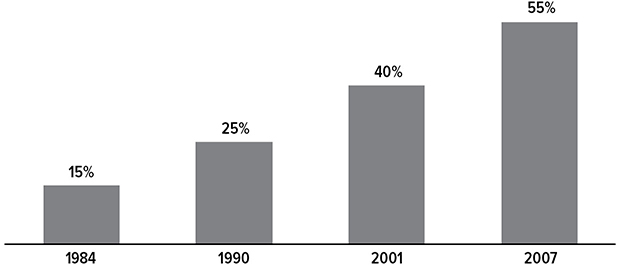

GE Capital kept expanding and quickly passed the 50 percent of profits threshold that most investors viewed as the absolute maximum size from a risk perspective. Deals became even larger and more complex, but Immelt kept investors happy by constantly churning the portfolio. They applauded the exit from insurance in 2004. But little did investors know that GE retained substantial tail-liability risk in several of its deals. Long-term-care insurance had the biggest impact. As losses on those policies piled up, despite the company’s best efforts to hide them, GE eventually took a massive $15 billion hit to reserves in 2018—a size that few could have ever imagined possible, particularly given the fact that many investors were led to believe GE had completely exited the insurance business via the IPO of Genworth in 2004 and asset sales to Swiss Re in 2005. (See Figure 2.2.)

Figure 2.2: Capital’s expansion began under Welch, but Immelt took risk to dangerous levels, over half of GE’s earnings at peak.

Source: General Electric filings

THE CULTURAL BREAKDOWN

Where was the rest of the organization, especially the board, as Immelt pursued these costly moves? It seems the GE board was charmed by Immelt. The board members benefited from his Augusta golf membership and access to GE aircraft, as well as choice seats at major entertainment events, along with attractive compensation packages. The Olympics served as an opportunity for directors and their spouses to “oversee” NBC. Top shareholders were similarly enticed to attend and were given seats on GE’s aircraft to make the trip.

Immelt seemed to favor directors with limited experience in GE’s core businesses. Most of the board had headline-grabbing names, but few ever actually dug into the businesses themselves or had ever managed something with this level of complexity. He also diluted vocal members of the board by keeping an unusually large board, typically around 18 members, while a normal size would be 12 or fewer. For reference, Apple has 8 board members, while Amazon and Google/Alphabet each have 10. A board size of 18 is considered dysfunctional by nearly every corporate governance expert on the planet.

The board had little incentive or ability to raise objections. Instead, with the stock price in the doldrums, the board sought different ways to justify executive pay. Immelt’s annual pay often exceeded $20 million, all while shareholders continued to lose from his poorly timed investments and lack of focus on operations. In total, Immelt was reported to have earned an eye-watering $275 million in compensation over his 17-year tenure, a tenure that twice nearly bankrupted the company.

Immelt’s senior team enjoyed similar celebrity treatment. One executive is reported to have had a hair stylist travel with her on the private jet. Another commuted back and forth to his family estate in Italy on GE planes. Most had multiple offices and access to apartments in major cities. Others were compensated far more than their peers in similar roles at other firms and had wide-ranging perks. One executive loaned money to a Brazilian customer that ended up in jail, losing GE hundreds of millions of dollars in the process. Another manager was involved in questionable revenue accounting that led to SEC fines. Finance heads were increasingly rewarded for obfuscation. Internal auditors were paid by the businesses they were entrusted to monitor. Honest reporting was viewed as unimaginative.

These excesses were established early on in Immelt’s tenure. When he went into biotech in 2003, he had to convince Sir William Castell, the CEO of Amersham, to sell the company. In return, Castell received not just the job of leading GE’s overall healthcare unit and a large salary but also a board seat and outlandish perks such as GE paying for the lease on his Rolls-Royce. Amersham was a rare Immelt acquisition that eventually paid off, but Castell was a terrible leader, and the healthcare business struggled for years until he was finally ousted.

When John Flannery took over as CEO after Immelt’s ouster in 2017, he told me a story about when he ran M&A for GE. Immelt walked into his office one day and asked if he was working on any exciting deals. Flannery responded that valuations were high, so they should consider selling some assets now and revisit buying another day. To which Immelt responded, “Don’t be a pussy,” and walked out. By the time Flannery had taken over from Immelt, it was clear that even he had little respect for his predecessor. He even asked me in an early get-together, with IR staff present, “When did you realize that Immelt was a fraud?” The question nearly knocked me off my feet. GE people, up to that point, had largely protected Immelt. Flannery didn’t last long in the seat; the company was too far gone at that point. Hardly his fault—he walked into a buzz saw.

While current GE executives are careful in their criticisms, rightfully focusing on the future, more than one has mentioned to me their surprise that the internal audit staff didn’t elevate concerns until well after Immelt was gone. We may never know where, when, and how the system broke down. In the absence of that knowledge, we have no choice but to assign responsibility for GE’s decline to the board and its CEO and chairman.

The reality is that every company struggles with the temptation to fudge numbers or, worse, to improve short-term results at the expense of the long term. The good ones have accountability systems that keep most people in line. There’s nothing that destroys a culture faster than wasteful spending and celebrity behavior among the executives. Every example of corporate failure we know about included exactly that. What employees see, they start emulating. Customers and suppliers eventually see as well, and the brand suffers.

By 2004, with profits no longer keeping pace with those of GE’s peers, Immelt worked hard to keep up a positive appearance. Besides buying aggressively and expanding Capital, the company issued earnings reports full of one-time gains and buried restructuring expenses. Losses typically went “below the line” in areas such as discontinued operations. The reality of an asset became secondary to how it could be presented. I asked Immelt in 2005 why he didn’t sell NBC Universal (NBCU), still valued at a solid $50 billion, even as it was coming under pressure from declining ratings. He said if the unit wasn’t worth more than $70 billion in three years, then he should be fired. In fact, he sold NBCU to Comcast in 2009, four years later, for all of $30 billion. Then Comcast managed to double NBCU’s earnings three years later. Even with all the competition out there, NBCU under a different owner is likely worth upward of $100 billion. The context is astounding. NBCU, which equated to less than 20 percent of GE’s earnings in most years prior to its sale, is now worth about all of what remains at GE combined. GE sold at the absolute bottom, leaving billions on the table. When I later brought up that conversation to Immelt in front of a small group of investors at an annual industry conference, he asked me, “When did you become such an asshole?”

GE’S FIRST NEAR BRUSH WITH DEATH, THE GREAT RECESSION OF 2008–2009

The Great Recession of 2008–2009 brought GE to its knees. GE was harder hit than most companies, due to its outsized exposure to financial services, its record-high debt levels, and a deep recession that was hurting even its strongest businesses. But even before the crisis accelerated, GE showed signs of cracking. On a March 2008 webcast to retail investors, Immelt had actually promised a good start to the year, only to host an earnings call just a month later when the company badly missed its earnings guidance. Then in 2009 he became the first CEO in GE’s history to cut its dividend, a devastating blow that he described as the worst day of his life. He had always felt connected to individual retail shareholders, especially GE retirees, which included his father. The share price sank from $40 to nearly $6. GE arguably would have gone under had the US government not come in and insured its short-term debt (i.e., commercial paper), which saved GE along with other financial institutions at the time. Except GE wasn’t supposed to be as risky as a bank. And just like most banks in late 2008 and early 2009, GE had to raise equity to firm up its balance sheet—in this case a timely investment by Warren Buffett.

In consistent form, GE fought hard against any accusation that it had lost its edge. In fact, on that April 2008 conference call, in which GE showed its first outsized earnings miss since the events of 9/11, I questioned GE about its struggles, even drawing the analogy of the Chicago Cubs baseball team that had long struggled to win and whose supporters optimistically used to joke, “We’ll get ’em next year.” My comments were admittedly a little emotional, partially because GE’s IR machine had assured investors all through the quarter that the economy was having no adverse impact on its businesses. It was an outright lie, and I found that one to be far more offensive than the usual tales GE would tell, particularly in light of the fact that just a few weeks prior, we had downgraded our industrial sector rating to a “sell” on our own macro concerns, and GE had gone out of its way to tell our clients that we were going to look stupid for the negative call.

Playing into all my greatest fears about the power of the GE machine, the company tried to get me fired that day—because Immelt found my comments “rude, offensive, and unprofessional.” I later found out that it wasn’t Immelt who made the phone call to complain about my words, but his longtime CFO, Keith Sherin. Sherin was a tough-as-nails sidekick who engineered much of GE’s financial complexity. While we fault Immelt throughout this chapter, Sherin played a key role in GE’s rising risk profile. I was later told that Sherin agreed to “allow” me to keep my job if I would apologize to him in person. We scheduled a private lunch at GE’s NYC headquarters in Rockefeller Center a few weeks after the call. It was a white-gloved, butler-served meal in a conference room on the executive floor, and I’m convinced that we were the only two people on that floor that day.

To be clear, I did not apologize. At that point, cooler heads had prevailed, but my career at Morgan Stanley suffered nonetheless. After that Friday-morning conference call, I spent the weekend fighting to keep my job. Shaken to the core by the reality that after more than a decade of unimaginable hard work and sacrifice as an analyst, I nearly lost it all. I did take a sizable pay cut in the end, which eventually catalyzed the conclusion that I had to leave the firm to restore my career. All because I had the gall to question Immelt’s strategies on the day of GE’s worst earnings miss in history. This was only months away from the company’s near collapse in the 2008–2009 financial crisis.

GE REEMERGES POST CRISIS

After the dividend cut and tarnished reputation in early 2009, Immelt finally started to shrink GE Capital and simplify the overall portfolio. Those efforts gained urgency when the Federal Reserve designated the company a systemically important financial institution—a step that brought the kind of governmental oversight that Immelt hated.

But as he reduced the company’s exposure to financial services, he needed something to replace the lost earnings. He settled on two big initiatives: digital transformation and the acquisition of a large French power infrastructure company named Alstom. With digital, Immelt saw enormous potential in the industrial internet and additive manufacturing (also known as 3D printing), and he wanted to supply the software as well as the hardware. He turned the company’s small IT support unit into a separate GE Digital division. It had the ambition and budget to become a world-class software house.

The digital foray won the company good press, but it would be many years of heavy investment before anything tangible emerged, and even then, finding new revenues was difficult. Unlike Welch’s focused bets, Immelt’s digital strategy had no specific digital product in mind, at least not one that customers were currently looking for. Instead it was more of a concept. “GE would become the backbone to the entire industrial internet” sounded sexy, but it wasn’t clear that it was necessary or even all that useful. Even with billions of dollars behind the plan, it was pretty much doomed from the start. By the end of Immelt’s tenure, nearly all hope of GE ever becoming a legitimate software supplier was gone.

In hindsight, many tech investors note Immelt’s lack of knowledge in the tech world, illustrated by his hiring of an executive from Cisco, a hardware provider, to build and run GE’s software businesses. His choice of location for GE Digital, San Ramon, California, was just not a place where high-end software code writers either lived or wanted to work. GE was only able to attract B-team programmers and had to pay up even to get those. The world of tech was so foreign to GE’s stodgy East Coast heritage that the clash was notable. In our visits to San Ramon, we were always struck by how out of place GE executives seemed. They would get off the plane in San Francisco wearing the more formal classic GE uniform, put on jeans and sneakers, and shazam!—they were transformed into tech guys. Talk about creating cultural confusion. In any event, initiative one failed terribly.

Immelt’s second initiative was to acquire Alstom, the big French maker of electric power generators, grid equipment, and power plants. Alstom was a poorly run rival with margins less than half of GE’s, and GE figured that its superior management capabilities could double those margins, all while finding outsized cost synergies in the merged companies. Alstom’s number four market share in gas turbines would boost GE’s number one share in a business already consolidated down to a few players, Siemens and Mitsubishi being the other big names. On the surface, the deal looked reasonable.

Investors did not know, however, that due diligence had revealed that Alstom was in poor shape, much worse than what anyone inside GE had previously thought, and GE should have walked away. But Flannery, still head of M&A, said later that he knew it would be career suicide to argue against the move. Making matters worse, the EU dragged out approval of the deal for more than a year, all while Alstom’s engineering and sales talent fled, new contracts were signed with terrible terms, and finances fell further into the abyss. To top it off, the EU then required GE to sell critical technology to an emerging competitor (Ansaldo) with Chinese ownership (Shanghai Electric). In gobbling up a key competitor, GE was forced to create a new one, which crushed all the benefits of consolidation in the first place. But GE pressed on, even raising its bid to $17 billion ($11 billion of it in cash) in order to beat out a joint bid from Siemens and Mitsubishi. GE also had to promise to protect current jobs in France and create new ones. In protecting those jobs, the crucial cost-cutting part of the deal model went out the window.

GE insiders say that power generation leaders warned Immelt that the deal was doomed, but he went ahead anyway. He may have felt he had little choice. In selling off most of GE Capital, he was eager to reposition around a “new GE,” and on paper the strategy made sense. The IR team presented a future 2018 earnings profile of $2.00+ per share, compared with $1.30 earned in 2015 when the target was announced. GE’s acquisition of Baker Hughes a year later seemed to provide another tailwind, all assuming that the demand for oil and gas, along with jet engines, healthcare, and, of course, gas turbines, would stay strong. Most analysts and investors, including me, thought this all made sense, pushing the stock up 25 percent in 2016.

With GE’s stock rising from its financial crisis low of around $6 to a peak near $32, Immelt regained credibility. He had seemingly engineered the exit from most of GE Capital and replaced those earnings with a higher-quality stream from core operations in power and in oil and gas. The fact that he was willing to bless a $2.00+ earnings profile for the company gave further confidence to that view, suggesting the stock had upside well into the $30s or higher. This was setting Immelt up to retire as the man who got GE through the horrors of 9/11 and the financial crisis of 2008–2009, with investors eventually rewarded with a rising stock price. We just didn’t know what many GE insiders knew: Alstom was nearly bankrupt.

HOW WRONG THOSE ASSUMPTIONS PROVED

Critical to the entire $2.00+ EPS (earnings per share) narrative was that the Alstom deal become a resounding success. GE soon discovered the full extent of the troubles at Alstom, but it kept them hidden, figuring it could fix things before losses expanded. But instead of stabilizing operations, the company accelerated its free fall. From then on, GE’s earnings and cash flow guidance became optimistic to the point of irresponsible, perhaps even pushing acceptable legal limits. Meanwhile, demand for gas turbines, along with oil exploration equipment, went south as the world economy slowed, and renewables began to rapidly replace traditional gas and coal power generation. Immelt had made an extension of Welch’s brilliant trades of the 1980s, but now the timing was badly off. This time, GE was on the wrong side of every bet it made.

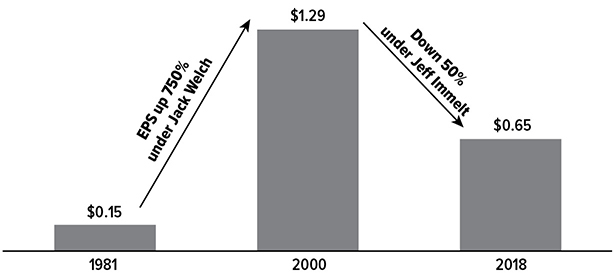

By 2019, GE had written off not just the entire $17 billion Alstom deal (valued at zero on the books), but far more and still counting as the business continues to bleed cash today. Instead of $2.00+ of earnings, reality ended up closer to $0.65 (and that’s a highly adjusted number with limited cash flow) and with a stock price that dropped from north of $30 all the way back to the financial crisis low of below $7, all coming after two dividend cuts, this time to basically zero. The Alstom deal now ranks as one of the all-time worst acquisitions in history, catalyzing the eventual firing of Immelt in August 2017. Contributing to the debacle was the hidden time bomb in what was left of GE Capital: losses in its legacy long-term-care insurance business.

As of early 2020, the Alstom debacle, combined with the high cost of GE’s liabilities, means GE continues to generate almost no cash flow, nearly crippling the company and forcing current management into crisis mode. Immelt had pressed every lever he could to make his actions appear sound. He borrowed money to buy back stock at inflated prices, and he pushed off restating liabilities at higher levels in hopes they would just go away. He put the company in such dire straits that crown jewels such as its fast-growing biotech business were sold just to keep it afloat. (See Figure 2.3.)

Figure 2.3: Immelt largely unwound the impressive results that GE gained under Jack Welch.

Note: Data is adjusted for stock splits.

Source: General Electric filings

FUDGING THE NUMBERS

It’s easy to blame the captain when the ship sinks, but Immelt wasn’t the only executive that drove the company toward bankruptcy, not once but twice in a decade. The old-timers talk of a GE that traditionally operated with a conservative, “round-down” culture. Forecasts included cushions to account for weather-related or macroeconomic disturbances. Market share was only one of several goals, and salespeople avoided high-risk customers. They had responsibility not only for landing a deal but executing on it.

That started to change even before Immelt. In the tech bubble years of 1999 to 2001, those who signed a contract were often not the same as those who had to execute on it. A team of dealmakers would come in with rosy forecasts, price a deal around perfect execution, then move on to the next opportunity. A separate execution team then came in and dealt with the realities of the project. Installing a giant power generator, for example, is full of risks, from suppliers to outside engineering partners to geopolitics. A turbine repair under warranty, for example, could cost a few hundred thousand dollars while the turbine remained at GE, but cost many millions of dollars once installed at the customer site. Project delays often came with severe penalties for GE, even if the causes were completely outside of the company’s control. Those risks were often ignored by those who negotiated the deals.

Meanwhile the accounting around GE Capital took the company one more step away from reality. Welch even spoke about the art of moving dollars around each quarter to manage the ups and downs of divisional results. Immelt simply deepened the behavior and raised the risk tolerance.

To boost sales and their own bonuses, salespeople gave more discounts and took on shaky customers. They offered more financing with longer terms and smaller down payments. In China, supposedly a GE strength, executives agreed to terms that produced short-term revenues at the cost of intellectual property. Technology “sharing” with local partners became technology theft.

While these troubles took place throughout the company, the power division was the worst offender, especially after 2015 as demand fell. Managers recorded sales on turbines before the units were field-ready. Units were installed with major flaws and did not work to promised specifications. To boost revenue from service contracts, managers used discounts to stuff the channel with as many upgrades as possible.

The result was declining real cash flow, much of it not disclosed in filings until well after the fact. GE’s PR and IR teams insisted that things were fine and the company was on track to meet its estimates. Cash, they said, was going to promote growth by extending credit to more customers and to develop new products. Any analyst who tried to probe got a brush-off or worse from Immelt or CFO Jeffrey Bornstein, who had replaced Sherin in 2013. When we wrote in late 2017 that GE should be investigated for deceiving investors and potential fraud, the company responded with a harsh rebuttal that was quickly repeated by more than a few news outlets.

Whether Immelt and his crew committed outright fraud will be determined by the SEC. We don’t have nearly enough information to make that judgment. Either way, we are skeptical that they will be held accountable in any real way. More likely, GE itself will be presented with a monetary fine for poor oversight.

As for Immelt, he found a new job and has shown little remorse. Shareholders understand the risks inherent in any investment, but GE was advertised as “safe.” Employees were told their jobs were secure. Retirees were told they could count on the dividend, and they favored GE stock in their 401(k) plan. These are the real victims, the ones who deserve to know the truth, the ones asking for accountability.

THE ENDING

By early 2017 there were signs that the great promise of a $2.00+ EPS laid out two years earlier had fallen flat. Even the powerful IR and PR teams were starting to hedge the outcome, blaming lower oil prices, the economy, the French government for Alstom, pretty much anyone or anything they could.

By May, Immelt looked old, tired, and beaten. He was gaining weight and stumbled through his midyear analyst update at the Electrical Products Group Conference, an annual get-together of about 150 influential investors and 25 or so top industrial company CEOs. I was in the front row, perhaps four feet away, and saw Immelt visibly shaking and sweating. I’d never seen him like that. Gone was the confidence he once exuded. On the side of the stage, his usually steady CFO Bornstein sat with his head down, unwilling to make eye contact. The entire experience was surreal. GE executives rip through PowerPoint presentations with ease. But on that day, Immelt could barely change the slides without stuttering. Within minutes my phone lit up with texts from those listening to the webcast, asking, “What is happening?” The press didn’t know what to say, how to report what had happened. GE, led by Immelt, was unraveling in front of our eyes.

By July it was clear that Immelt could no longer do his job, and I wrote a draft of a report calling for his resignation. GE became aware of our work from a fact-checking phone call we made and asked us to delay the report for a day, offering a private meeting with Immelt instead. I saw little harm in waiting a day and was still well aware of the power that GE held. Investment bankers were still collecting big checks from GE, and my new employer, Barclays Bank, supported my independence . . . to a point. Anything I wrote that criticized GE needed to be 100 percent accurate. A report calling for Immelt’s ouster would be headline news that day, so the work had to be immaculate. I went to hear Immelt’s rebuttal.

Visiting the Boston headquarters and sitting in Immelt’s private conference room, I was shocked at the conversation—more a confessional than the aggressive and confident Immelt I was used to. A visibly shaken Immelt apologized for how the company had “screwed me,” not just for providing the wrong numbers for our analysis, but also for the regular beatdowns from his team. In battle, there are casualties, and it was clear that I was one of many in this war. In a shaking voice, he admitted the $2.00+ earnings guidance provided in 2015 was just a “holding place,” that he needed to anchor investors on something hopeful to offset the pain taken in exiting GE Capital. He spoke for a long time without stopping, all while looking down at the table between us. He insisted he and others in the company had no idea Alstom’s power division was in such terrible shape. He insisted that all the problems during his tenure were just bad luck, that Welch handed him a “bucket of shit,” that he protected Welch’s legacy at his own expense. And he further insisted that he got GE through its toughest time period, the financial crisis of 2008–2009. He rambled somewhere between apologizing and not. What was supposed to be a half-hour meeting went on for more than an hour. It wasn’t clear what he was trying to accomplish, but he looked like a man living a very big lie and needing to get it off his chest.

From there I sat separately with CFO Bornstein, and the tone was similar. Bornstein had always treated analysts with contempt, usually lecturing us with a scowl. His voice typically boomed. But this time Bornstein blamed the company’s failures on the culture’s unwillingness to address costs and its bloated ranks. There were fiefdoms all over the world too powerful to break, and there was too much competition among the divisions. He blamed the contest to succeed Immelt for preventing bad news from traveling up and cost mandates from filtering down. He looked lost and weakened. It was clear that his career, as well as that of his mentor Immelt, was over.

I walked out shell-shocked. I had agreed not to write about “anything new discussed in the meetings,” which had pretty much made my report obsolete. Everything was new. And any thought of downgrading the stock and advising my clients to sell was out the window. Now I was in possession of material nonpublic information, which carries a legal obligation to maintain confidentially until the information is made public. Both men had all but admitted that GE was in dire straits, that the company had little chance of making earnings numbers, and that the Immelt era was clearly over. At that point, any report calling for Immelt’s resignation was irrelevant. He was already gone; just the details of his exit had to be worked out with the board. As we expected, he “quit” a few weeks later, pushed out by directors finally responding to the intense pressure.

Immelt likely knew this was going to happen before we met. I believe he was meeting with me to try to damage-control the narrative of his legacy. Although Immelt always claimed to be thick-skinned, negative press impacted him greatly. He wanted to leave on his own terms, but with the stock in free fall and an activist pushing for change, his fate was already sealed.

John Flannery succeeded Immelt as CEO in August 2017 and immediately instituted a broad review of the company’s operations and accounting. On his first day on the job, he called my cell phone, and we spoke for a few minutes. At the end, he said, “I want to be very clear. There will be substantial change. I care about shareholders, and I want an open dialogue with my owners.” I met with him one-on-one a few months later, and he had a similar shareholder-friendly tone. But the question he asked me on that day, that I mentioned earlier in this chapter, still haunts me: “When did you realize that Immelt was a fraud?” Without hesitation, I said it was that day in Dallas back in 2003, when he had spoken as if he were already the most accomplished CEO in the world, a renowned leader whose time was too valuable to use a hotel gym or stand in the typically short line at the Four Seasons Hotel check-in counter. He was so caught up in being a celebrity CEO that he forgot he worked for shareholders—and more broadly for stakeholders.

In truth, however, I myself had forgotten that early warning sign over the years. I had allowed GE’s leaders and investor relations machine to explain away problems. I tried to stay strong and call out abuses, but after years of intimidation, it was just too much. In the process, I failed many of my clients. I just didn’t want to believe that such a great company could allow so many deceptions. These were people I had once greatly admired. The lessons are hard, raw, and humbling. It still feels surreal—a bad dream that I haven’t yet awoken from.

POSTMORTEM OF THE JEFF IMMELT YEARS

At its core, GE failed stakeholders because it invested its abundant profits unwisely and took its past success for granted. It relaxed its heretofore impressive management discipline around operations and sales. Then it pushed the envelope of risk higher each year to compensate for the prior year’s shortcomings. It also insulated itself from accountability, which is essential to any effective business system.

A contributing factor was that Immelt and his team allowed the company to get too big and complex for effective oversight. (See Figure 2.4.) At their best, conglomerates spread risk, promote global scale, and centralize strong governance, but too often their size breeds overconfidence, and they use their complexity to hide problems. Some conglomerates do succeed (see later chapters in this book), but it takes more management discipline than most companies can muster.

Figure 2.4: GE’s value destruction (in market-cap terms) was nearly two times that of WorldCom, Enron, and Lehman Brothers combined.

Source: Bloomberg

GE’s diversification worked well in the 1990s, but it was a tangled mess soon after. Near the end, and with margins under pressure, GE put almost all its free capital into two areas. Much of it went, reasonably enough, into the thriving aviation division, which rode the continuing global boom in air travel, but the rest went largely to fixing GE Power, ultimately with the Alstom acquisition. That left the healthcare division starved of investment. GE made no real acquisitions in healthcare throughout the 2010s, a decade of major innovations in that industry.

GE was drowning in complexity, which would have made it hard even for disciplined leaders to hold people accountable. KPMG was charging the company $143 million annually in audit fees, involving 21 partners and hundreds of accountants. GE’s tax filings ran into thousands of pages. With an engagement that big, as we saw with Arthur Andersen and Enron, it’s hard to trust the findings. There are many gray areas and boundaries that can be pushed. It took Flannery several quarters to understand what was actually going on in the company, but by then it was too late, and he was slow to react to a sharply degrading GE. The board fired him for inaction in October 2018. Perhaps it would have been impossible for any insider to unwind Immelt’s GE.

In early 2019, new CEO Larry Culp committed to whittling down the company to the core aviation, healthcare diagnostics, and power businesses. He pushed out nearly all the legacy board members and replaced the senior corporate staff. And he has promised to repay debt and get GE back to financial credibility. Those actions may do a lot to dig the company out of its mess—and Culp is a high-integrity leader—but they may not be enough. GE as a brand may be irreparably damaged, even with businesses sold or spun off over the next few years. The financial damage done to the entity makes it less clear that GE can fully weather a deep recession as it has many times in its century-plus existence. That part of the story remains to be seen.

IF IT COULD HAPPEN TO GE . . .

It’s easy to present GE’s story as a morality tale. Extraordinary success went to everyone’s head, GE lost its edge, and the company made things worse by chasing unprofitable short-term fixes. But GE was more than a century old when Immelt took over, and most of its leaders had grown up in the company. GE invested more in management development than most companies, and headquarters actively oversaw the divisions. The company was famous for its systematic approach to business, and it had adapted successfully to previous challenges.

As for Immelt, he was fully a product of “the most admired company in America.” He had excelled as head of the healthcare division, and Welch had selected him after a rigorous succession process. Immelt worked hard to envision a new course for the company, including substantial efforts to digitize the businesses. He also had plenty of smart people who could see problems as well as anyone out there. If that kind of organization can fail so dramatically, then every company is vulnerable.

That’s especially true of the high-flying tech companies that dominate attention and investment today. We’ve seen disturbing parallels between their actions, especially on disclosure and accountability, and what we faced with GE. It’s human nature: any company that thinks it’s special, that the ordinary rules don’t apply, will eventually stop doing the exceptional work that brought about its initial success. The distractions of success and celebrity can be overwhelming.

GE’s struggles show the difficulty of maintaining focus over decades, especially across CEO transitions. How do you achieve and sustain the discipline necessary to prevent the kind of irresponsibility and arrogance that plagued GE? What kind of leadership, systems, and incentives will focus people on sustained profitability—not on a dressed-up fiction that serves only short-term interests? That’s what we explore in the rest of the book and for which we hope to offer insights. Because for every sad corporate failure like GE, there are winners equally worth studying. Taken together, the lessons are extraordinary.

Lessons from the Jeff Immelt Era