CHAPTER

9

TRANSDIGM

How to Turn a Million into a Billion

![]()

Wall Street has a tendency to oversimplify. Hours are long, and time is money; there’s little room for complication. From the time a rising senior in college is working as an intern all the way through his or her eventual promotion to portfolio manager or managing director, the skill of delivering an effective elevator pitch is trained, retrained, and refined. If an investment thesis can’t be distilled down to its key points in the time it takes to ride an elevator up or down, then it must not be worthwhile.

For TransDigm, a Cleveland-based aerospace parts company, the elevator pitch, since the time the company went public in 2006, has been something like, “It’s a collection of acquired aerospace monopolies with outsized pricing power.” These days, most of the publicly available content about TransDigm paints the company as an overleveraged and opportunistic price gouger. This is an oversimplification. Yes, TransDigm’s story does include debt and the serial acquisition of companies with strong market positions. But it doesn’t stop there. TransDigm would still be successful with a fraction of the price increases that the company has enjoyed over the years. This is because every day, from the factory floor to the C-suite, the people at TransDigm only focus on what truly matters for their consistent success.

This chapter is about an organization that compounds value at an extraordinary rate. It’s about the power of a business model built on strategic and operating discipline and a relentless focus on the drivers of value creation for the company’s owners—its employees and investors. It’s about the optimization of internal and external investment as well as capital and cost structure. Many of the successful industrial companies we discuss in this book have very formalized businesses systems; TransDigm isn’t one of them. However, any lack of formality is more than made up for by the company’s strict adherence to its core principles of value-based pricing, productivity, and profitable new business.

GREAT BUSINESSES SITTING IN YOUR LAP

Anyone who’s ever been on a commercial flight knows what an aircraft seat belt looks like and how it works. I bet you can picture the exact look and feel of the buckle and hear the flight attendant over the PA system saying, “Fasten the belt by placing the metal fitting into the buckle, and adjust the strap . . .” Why is it that almost every aircraft seat belt has a buckle just like the one you’re imagining?

That’s because almost no one but the maker of the original buckle has ever certified other designs with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). As a result, a company named AmSafe accounts for more than 95 percent of the global aircraft seat belt market.

How good a business is airplane seat belts? After all, it’s only three pieces of metal and a spring. Well, you can ask TransDigm, which paid $750 million for AmSafe in 2012 and has generated a 20+ percent return on its investment. Aircraft seat belts are a fantastic business, especially in the right hands.

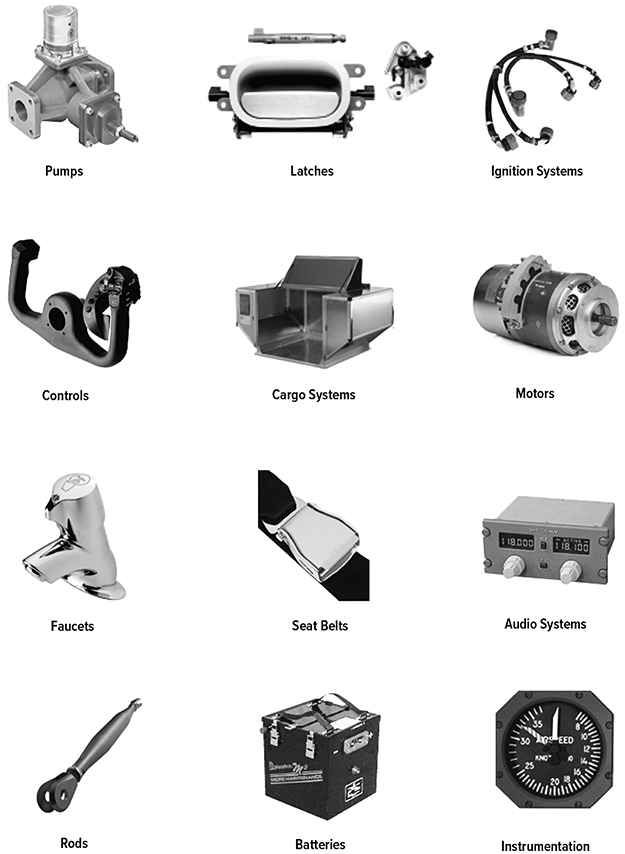

Look inside TransDigm’s product portfolio, and you’ll find thousands of other widgets that don’t appear complex. Products incorrectly deemed “crappy” because you literally find them in the airplane restroom: lavatory faucets, drain assemblies, and door locks. Then there are overhead bin latches and extruded plastic vents that push cold air into the cabin, along with a litany of valves, pumps, cables, and connectors that all play a role in the flights of millions of people around the world every day. (See Figure 9.1.)

Figure 9.1: TransDigm’s product lines don’t look particularly complex to the untrained eye.

Source: TransDigm

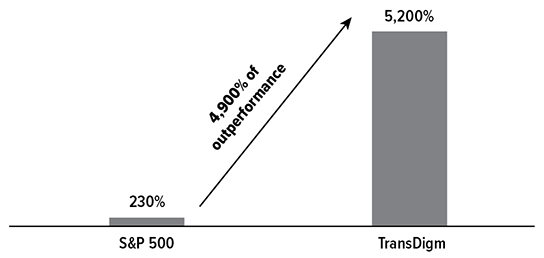

These businesses are phenomenally profitable, and they’re all owned by TransDigm, which has fully understood and maximized the returns from each of them. Through 2019, prior to the disruption caused by the COVID-19 crisis, the value created from these businesses made TransDigm the best-performing stock in industrials since the company’s 2006 IPO, increasing by roughly 50 times over, including dividends. A company that started with an initial equity investment of $10 million 25 years ago grew to an enterprise value that was thousands of times larger (See Figure 9.2.)

Figure 9.2: Prior to the disruption of COVID-19, TransDigm outperformed the S&P 500 by 4,900 percent since its IPO.

Source: Bloomberg

Note: Data is as of year-end 2019.

WHEN WALL STREET WAS SKEPTICAL

When TransDigm became a publicly traded company, Wall Street was initially more skeptical than optimistic. The company carried a large debt load, had changed hands in the private equity world three times, and had profit margins that were 20 points higher than any other aerospace company. When the company came to the public markets via an initial public offering, many didn’t understand what TransDigm really was.

Investors are inherently skeptical toward most IPOs, especially for companies coming out of private equity ownership. Private equity firms have a reputation for gutting companies and overburdening them with debt before dressing them up for sale to institutional investors that they hope won’t be able to tell the difference.

When TransDigm went public in 2006, it was the height of good times on Wall Street. IPOs were abundant, and investors could afford to be picky. As a result, the investment community was on the lookout for anything to dismiss an offering as imperfect. In the case of TransDigm, the combination of financial leverage, profit margins that appeared unsustainable, and the history of private equity ownership was all it took to generate skepticism. Few took the time to understand how TransDigm had been such a strong financial performer historically or why things would continue to get better. Early on, no one fully grasped the company’s long-term potential.

In the years following the IPO, I gained a deeper appreciation for how the company worked and how its business model fit into the aerospace ecosystem. (See Figure 9.3.) My aha moment came during a meeting with former CEO Nicholas Howley and a TransDigm investor. In an effort to knock Howley off balance, the investor forcefully asked him why he should believe in the company following Howley’s recent sale of millions of dollars of stock. Howley stunned me when he sat up in his chair, put his elbows on the boardroom table, looked the guy in the eye, and said: “This may come as a surprise to you, but I’m in this for the money. I haven’t had many chances to sell stock under private equity ownership, and now I do. My wife wants a beach house. So we’re gonna get a beach house. You can believe what you want, but I’m not going anywhere. I’ve got more money to make, and if you choose to, you can make it with me.” This told me almost everything that I needed to know about TransDigm. The CEO was planning on making more money, but how exactly was he going to do it?

Figure 9.3: TransDigm’s history (1993–2019).

Source: TransDigm filings, press reports

UNDERSTANDING TRANSDIGM’S MARKETS

Airlines have long asked themselves whether they want their spare parts to be safe or cheap. Unsurprisingly, safety and reliability always come first. As a result, today you’ll find that for every part on a specific class of aircraft, there are often only one or two suppliers, and they have been manufacturing the same part for 70+ years. These companies build on prior engineering and manufacturing know-how, existing capital and certification investment, and track records of safety and reliability to create mini-monopolies that enjoy sales of specific aircraft parts for decades with low levels of competition and reinvestment. These competitive and regulatory moats make the aviation supply chain home to a lot of good businesses, the best of which make money selling low-cost, relatively high-priced spare parts for the ~30 years that an aircraft is in service.

The highest profit margins in the industrial world are in the aerospace aftermarket. General Electric makes 60 percent margins on replacement turbine blades; spare brake pads generate 70 percent margins for companies like Honeywell and United Technologies; and navigation software updates can approach 100 percent margins.

A large portion of the aerospace parts industry is built on a razor/razorblade business model, where the original equipment parts are sold to Boeing and Airbus for very little profit or a loss. Many years later, when that same part requires replacement, it is sold to an airline for a price that is a multiple of the original price charged to the aircraft manufacturer. Spare parts demand is generally stable, as parts are replaced regularly and planes are constantly flying.

The older an airplane gets, the more expensive it becomes to operate. This leads to shrinking fleets, as older, more expensive planes are retired or used less frequently in favor of newer, more efficient aircraft. By this time in an aircraft’s life cycle, the likelihood of an alternative part being certified is increasingly low—new entrants struggle to justify the engineering and regulatory investment required to sell a new part into a shrinking market against an already established and trusted competitor. This allows the legacy manufacturers to push through annual price increases more aggressively. This pricing power more than offsets the declines in volume and justifies keeping production lines running efficiently, as incoming order velocity slows. These parts generate a ton of profit.

For most large aerospace companies, these highly lucrative parts are produced alongside far less attractive parts that don’t earn anywhere near the same level of profit. Take United Technologies, where a super profitable brake business is tied up with metal landing gear, which is a capital-intensive and non-spare-parts–generating business with low margins. And that’s just one example. The aerospace industry is littered with collections of good businesses alongside bad ones—except at TransDigm.

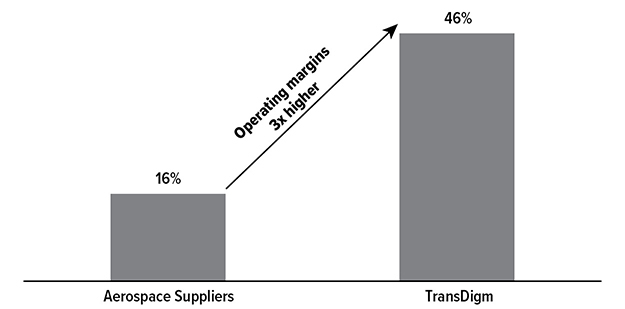

The average operating profit margin in the global aerospace industry is ~15 percent. TransDigm’s is ~50 percent. (See Figure 9.4.) This is partially based on the purity of TransDigm’s portfolio, which is made up solely of “proprietary aerospace businesses with significant aftermarket content.” There are no bad businesses, which allows the company to enjoy the pricing benefits of being a sole source supplier without dilution from weaker business models. However, it’s also a function of TransDigm’s laser focus on its value drivers.

Figure 9.4: TransDigm has operating margins 3x higher than that of peers.

Source: Company filings

Make no mistake: it’s unlikely that many businesses possess the same opportunity set as TransDigm, given the unique engineering and regulatory influences and brand/reputational entrenchment in the aircraft parts market. However, when you learn that many of TransDigm’s businesses were actually acquired from the companies that make up the ~15 percent average, you begin to wonder what TransDigm has realized that everyone else hasn’t.

TransDigm’s core philosophy rests on a few key value drivers. They sound very straightforward and perhaps too simple to be true, but what makes them so powerful is how they have been consistently applied to a thoughtfully crafted portfolio of product lines and managed by an organization incentivized to maximize their value.

THE THREE VALUE DRIVERS

TransDigm is remarkably consistent in the application of what it calls its three value drivers: (1) value-based pricing, (2) productivity, and (3) profitable new business. It’s a basic formula that requires masterful execution to get right. What’s proved amazing over the years is how many levels of financial, strategic, and organizational discipline have been simultaneously layered on to achieve these seemingly simple goals to remarkable success.

Value-Based Pricing

For some that have looked at TransDigm over the years, the concept of value-based pricing is perceived as equivalent to leveraging monopoly positions to aggressively raise prices to unfair or excessive levels. However, it’s worth noting that the company’s overarching pricing strategy isn’t particularly unique vis-à-vis other peers in the aerospace supply chain. In fact, when the Department of Defense audited TransDigm’s pricing in 2018, it revealed that several industry peers were also raising prices on comparable products. Everyone raises prices; TransDigm just has a purer portfolio and is more focused on extracting appropriate value commensurate with the types of parts that it produces. For every part, TransDigm is maniacally focused on earning an appropriate economic return. That means that as older planes are retired and production runs of spare parts become less frequent and more challenging to predict, TransDigm demands that it be compensated, not just for the direct cost of the part, but for the costs of keeping production lines “hot” with skilled labor and working machinery. The company takes reliability seriously, and it expects to be paid for delivering a high-quality, usable part quickly. This mentality of driving an appropriate level of value out of every order is ingrained in the product line managers across the company. But how long can annual price increases approaching 5 percent really last?

TransDigm’s pricing strategy remains sustainable because of three key factors: (1) regulatory, (2) economic, and (3) customer behavior. On the regulatory front, the time-consuming and costly FAA approval process for new parts creates a high barrier to entry. There are also the simple economic challenges of trying to compete against one of TransDigm’s product lines. Many of TransDigm’s parts are ordered in low and varying volumes and at infrequent intervals. Consequently, third parties often find the cost of investing in capital equipment and engineering expertise not worth the potential return. This dynamic is compounded by airline customer behavior. For an airline, the price points across TransDigm’s portfolio of parts are relatively low. Seat belts cost a minuscule fraction of what a spare part for an engine costs, but an airline needs both in order to be cleared for takeoff. TransDigm’s history of consistent on-time delivery and quality performance makes it rare for customers to switch providers. The risk isn’t worth it. Airlines cannot afford to miss out on several hundred thousand dollars of revenue if flights are canceled because a $200 spare part is not delivered on time or to specification. In addition to having a smartly constructed portfolio of product lines that are able to bear consistent price increases, TransDigm is also one of the best companies at consistently wringing cost out of its businesses.

Productivity

TransDigm’s productivity directive is focused on keeping annual growth in aggregate cost below inflation, year in and year out. This doesn’t sound as revolutionary or as flashy as Lean or Six Sigma, but the general goal is easy to understand and communicate down to individual product lines.

Take a walk through any TransDigm facility, and you won’t find anything extravagant. However, if you tour that same factory year after year, you’ll find that the manufacturing footprint usually shrinks and the number of employees doesn’t grow much, even as sales volume rises. Management consistently finds ways to eliminate employees who don’t serve a value-creating function, and the company closes or consolidates factories to optimize TransDigm’s broader manufacturing footprint. This reflects how dispassionately the company approaches evaluations of cost. When TransDigm acquires another company, it often relocates that company’s manufacturing footprint into the space saved by previous productivity efforts.

Since the company’s 2006 IPO, the company’s sales have grown ~15x, and head count has grown by only ~13x, while floor space was tightly managed. This is a testament to the company’s consistent push on improving productivity year in and year out. Despite pushing hard on both the price and cost front, TransDigm has not lost sight of the need to feed the business’s long-term growth by winning profitable positions on next-generation aircraft platforms.

Profitable New Business

When it comes to pursuing new business, it is underappreciated how much time, effort, and money many companies expend chasing new opportunities that are unlikely to turn a profit. Many of the companies referenced in this book have employed teams of business development professionals who toil away at evaluations of growth opportunities with new customers or within new markets. However, their success isn’t often judged by whether or not the opportunities result in profitable growth, merely sales growth alone. This is not the case at TransDigm. The company does not entertain business development efforts unless they offer a clear path to profits. There are no exceptions. Even with these strict principles, the company has been broadly successful in its new-business generation efforts. It has gained share on most next-generation aircraft and has done so with a tightly managed R&D and capital expenditures budget. Wasted effort is kept to a minimum.

TransDigm understands the difference between good parts and great parts, and it deliberately built a portfolio of companies that could compound the maximum amount of value over time. There are other aviation businesses that fit the TransDigm profile, but in many cases, they’re not employing the same principles to the same effect. Often there are fantastic product lines within larger companies, but the manager that runs them is on autopilot because his or her business is an upper-quartile performer in a sea of mediocrity. TransDigm doesn’t allow that to happen. All of its business units drive price, increase productivity, and win new business. The culture, the principles, and the compensation structure simply don’t tolerate good if it comes at the expense of great.

NOT AS EASY AS IT LOOKS

A few years after TransDigm went public, the market gained familiarity with the TransDigm story, and the investment banking world was buzzing about a copycat firm running the TransDigm playbook in the private markets. The company was called McKechnie Aerospace and was nicknamed TransDigm 2.0 by investors. A McKechnie executive admitted to me that his company was simply trying to replicate TransDigm’s success.

Before McKechnie ever had a chance to go public, TransDigm acquired it for $1.3 billion. At the time, the deal was the largest in the company’s history, and many questioned how much value TransDigm could create since McKechnie was already a TransDigm “clone.”

The McKechnie executive I knew was shown the door months after the deal closed, but he was there long enough to gain perspective on the differences between the two organizations. Shortly after he was let go, he told me that he was blown away by the TransDigm leaders. He said, “These guys are so much better than I ever imagined. . . . I totally underestimated how they do what they do . . . it’s crazy, because every day we were trying to copy them.”

Over the years, TransDigm’s operational discipline has gotten far too little attention. And this discipline extends beyond the factory floor and the sales department. It touches so many other functions that amplify the value generated in the production facilities.

ALIGNING EVERYTHING AROUND VALUE MAXIMIZATION

TransDigm spent its first 13 years owned by private equity. With that experience came lessons that took the business model and put it on steroids. Private equity ownership certainly isn’t without its problems. It’s not uncommon for perfectly healthy businesses to be crushed under the burden of high levels of debt, cost cuts that run too deep, or decisions by owners who lack the operational or industry expertise to successfully navigate a business cycle. Other times, however, companies like TransDigm emerge from private equity ownership as more efficient organizations.

After it exited PE ownership, the company retained two core beliefs from its experience: (1) thoughtful cash deployment and a well-designed capital structure were tools for creating additional value, and (2) employees should think, act, and be compensated like owners.

With capital allocation and capital structure, TransDigm realized that a business built with a high degree of recurring revenue from spare parts, pricing power, low volatility in input costs, and limited capital requirements could shoulder a higher debt load than an average business. The extra capital raised could be deployed toward the acquisition of other parts manufacturers that fit TransDigm’s model.

In the company’s first 25 years in existence, it acquired more than 60 other businesses (such as AmSafe and McKechnie) and paid $7 billion in dividends. This was from a company that started with four small businesses and an initial equity investment of just over $10 million. (See Figure 9.5.)

Figure 9.5: TransDigm acquired 60+ businesses since 1993.

Source: TransDigm filings

The average company acquired by TransDigm had 20–30 percent margins upon deal closure, but within a few years TransDigm would often pull this up to nearly 50 percent, just by applying the company’s operating model. The financial returns from these deals amplified the profits generated by TransDigm’s core operations. Perhaps most importantly, TransDigm has never done an M&A transaction that strayed from its core competencies or diluted its overall portfolio of assets. In the event that an appropriate M&A deal is not available, TransDigm doesn’t reach; it simply pays out its excess cash as a special dividend and waits for the right deal.

These elements are not top secret or unavailable to TransDigm’s peers, but they are rarely utilized. This is mostly due to organizational constraints deemed too significant to overcome: capital structure limitations and broader incentive compensation plans that are a function of scale, a suboptimal business mix, or a focus on factors other than profits and cash flow.

WORK HARD, GET RICH

I’ve had the opportunity to be around the TransDigm culture for almost 15 years. The people there work harder, sleep less, and make more money than at any other company I’ve ever encountered. If you’re a typical product line manager in an average industrial business, you likely take home $250,000 in annual compensation. That same product line manager at TransDigm can make $1 million. Every employee in every role is focused on the company’s value drivers, and in return every employee gets to share in the rewards. The pace is demanding, and it’s not for everyone—if you can’t keep up, the company is quick to show you to the door. Of the top couple of hundred people that make up the company’s leadership team today, nearly 90 percent were homegrown and internally promoted. Many of them are multimillionaires, and a handful are hundred millionaires. All this wealth creation is the result of a compensation plan that reinforces the desired outcomes.

TransDigm aspires to generate annual growth at a level that it characterizes as “private-equity-like.” This equates to 15 to 20 percent over a number of years. The belief is that if the business can consistently generate that type of growth, sizable stock returns will follow. And at TransDigm, stock awards comprise a large share of overall employee compensation. The company is convinced that in order for the business model to work, those in charge of executing the strategy need to be compensated as owners. If managers effectively execute to the plan, they are compensated with stock that has the potential to appreciate well beyond the initial value of the bonus. I know TransDigm “retirees” who still have younger children and not a single strand of gray hair. They came in early, worked hard, were appropriately rewarded by the company, and then left with their riches.

WHY DON’T WE SEE THIS LEVEL OF SUCCESS ELSEWHERE?

I’ve had several conversations about TransDigm with an aerospace industry executive at another parts company. He often asks me, “Why do you like those TransDigm guys so much?” before criticizing the company’s model as too aggressive on price and built solely on acquisitions—a Ponzi scheme waiting to unravel. I concede to him that while the company is not alone in its pricing posture, it does sit at the higher end of the peer group for the reasons noted previously. I also emphatically point out that this is just a fraction of its success story.

This executive manages his company differently from the way TransDigm is managed in several respects, not just pricing. His company’s portfolio features products that are both darlings and duds, and his business employs countless people whose contribution to the bottom line is unclear. Employee compensation is tied to the success of other business units that have nothing to do with day-to-day operations. The business is managed top-down to protect large pools of profit derived from large customers, rather than to maximize the value from each aerospace part in a bottom-up fashion. It is a remarkably dissimilar approach. These divergent strategies are best evidenced by TransDigm’s 2018 acquisition of Extant, a company that acquires intellectual property rights to “dying” lines of old aircraft parts that companies decide they no longer want.

Picture this: A business line manager at a large company looks at the list of products in her business unit and says, “I could grow this operation’s revenues faster if I could get rid of the stuff that’s shrinking.” She finds products that go on older aircraft no longer in production, where inventory turns slowly and innovation is scant. If she gets rid of these parts, her business’s overall growth rate goes up over time, and her inventory goes down. Depending on how she’s being paid, which most often is by sales growth, she’s a hero.

There’s only one problem with this picture: these products often have the highest potential profit in the portfolio. They have the best pricing power, and they require little or no ongoing investment. The fact that managers were allowed to sell such product lines to Extant is crazier than anything TransDigm has ever done.

Many companies, especially those in the new economy, can learn an important lesson about value creation from the TransDigm/Extant example. At technology companies, growth is often emphasized above anything else. However, abandoning high-margin and high-return products when they slow or stop growing leaves significant value on the table. A lack of appropriate focus can push companies to make decisions that cause them to miss out on the full maximization and monetization of their previous efforts. This is a misstep that we’ve seen many companies make, and it’s an error that TransDigm has taken full advantage of.

POSTMORTEM

To the untrained eye, TransDigm’s collection of pumps, valves, and switches isn’t particularly exciting compared with the product lines of other aerospace companies or those in the tech world. However, TransDigm has proven that even “boring” businesses can be extremely lucrative when focused strategic and operating principles are applied relentlessly.

TransDigm has consistently created value with every dollar of capital invested. Its persistent focus on price and cost, combined with secular tailwinds from growing air travel, has generated significant profits. Those profits have been diligently reinvested in similar businesses where the same value drivers can be applied, and waste is minimized. The business model is kicked into overdrive by the thoughtful addition of leverage and employees who are compensated as owners. There are always hiccups, but over any measurable period, value is consistently created.

The COVID-19 pandemic will inevitably put TransDigm to the test, as a lack of flying by the general public will hit aerospace suppliers hard in 2020. TransDigm will not be immune but the company’s strong operational discipline and dispassionate adherence to its principles of value creation will almost certainly see it emerge from the crisis in a better position than peers. Over time, passengers will return to the skies and airplanes will consume spare parts. When that happens, the TransDigm model will again be on display.

At the end of the day, there is an ongoing debate about whether TransDigm is cheating through aggressive pricing or simply doing things much better than everyone else. While that debate rages on, TDG continues to succeed by knowing exactly where and how to apply effort, focus, talent, and capital. If nothing else, TransDigm has shown that even good businesses can often be much better. Good is simply not enough, and greatness often lives in organizing everything around the core value creation engine of a company. TransDigm is what great looks like. Other businesses and their leaders can be well served by understanding the discrete advantages of their end markets and product lines and designing an operating and financial system that aims to maximize those characteristics.

Lessons from TransDigm