CHAPTER

8

ROPER

The Amazing Untold Story of Brian Jellison and His Timeless Lessons on Compounding

![]()

Roper’s success stems from the power of compounding, investing cash into higher- and then . . . even higher-returning assets. For all the value that was created over time at Roper, it all came from a simple acquisition model, a singular management philosophy, and a one-variable compensation scheme. That touches on something we may fail to highlight enough in this book. In all the ways that smart people can complicate all forms of business, the best of the best just seem to focus on a few basic drivers of value. Roper is perhaps the best illustration of this dynamic.

Roper’s unconventional CEO, Brian Jellison, saw the market for M&A stuck in an old paradigm—one that undervalued true cash flow, misunderstood the future capital needs of asset-intensive businesses, and overlooked hidden potential liabilities like healthcare, environmental, and pension costs. Jellison’s vision itself was basic—focus on generating cash flow, invest that cash flow opportunistically, and employ capable leaders to run newly acquired assets. He articulated a framework for success and then got out of their way. Sound familiar? It’s perhaps closest to the strategy employed by Warren Buffett. Not exactly a new model, but shockingly underutilized.

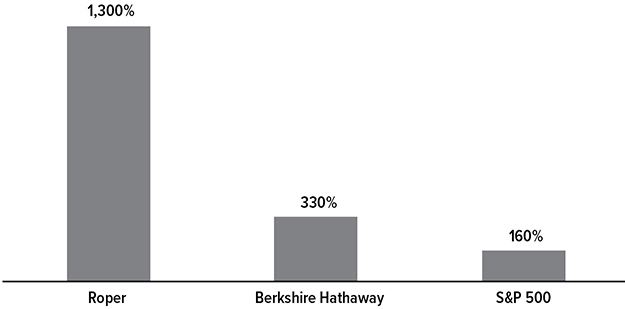

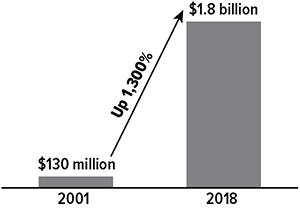

From a shareholder return perspective, the 17 years of Jellison’s leadership, from 2001 to 2018, were outstanding, making even amazing companies like Berkshire Hathaway look pretty darn average. The stock during the Jellison tenure returned 1,300 percent, rising from $20 to $300. That 1,300 percent quadruples Berkshire’s return of 330 percent. The overall S&P had a fantastic two-decade run, up 160 percent in that time period, but achieved only a tenth of Roper’s return. (See Figure 8.1.) A wide set of stakeholders went along for the ride: debt holders were rewarded with high and consistent cash flow, employees gained career opportunities and wealth that go along with a winning organization, and customers benefited from a supplier committed to investing in its value-added products.

Figure 8.1: Roper stock massively outperformed during Brian Jellison’s 17-year tenure.

Source: Bloomberg

Few companies in American history have treated stakeholders so well and with so little drama. There were no near-death experiences or huge market gyrations like we’ve seen so commonly with others. It’s a company that we have never once had an incoming press call on, even after the death of its visionary. Roper found comfort in remaining off the radar, focusing on the day-to-day power of compounding returns and letting the results speak for themselves. No advertising budget or PR campaign. Just a quiet and steady focus on the power of investing cash flow in higher-return assets and using those cash flows to reinvent its portfolio from its cyclical industrial roots to a higher-return, more predictable software future. By 2001, American businesses had lost focus on cash flow, just when that cash was so valuable. Jellison exploited this market inefficiency over and over in a remarkable 17-year run.

Unfortunately, Jellison isn’t alive to tell his own story. He passed away in the fall of 2018, shortly after he had stepped down from the CEO role. The nuances of his success may never be known, and we are left to piece it all together from personal interactions with him and those who worked alongside him. At times grumpy, he viewed Wall Street with disdain. He once dressed me down in front of a dozen of my best clients for asking a question he deemed stupid. He was dismissive of critics. He worked his staff hard and worked himself even harder. He was at times a tough, seemingly distant man. All the brilliant ones are restless, with notable flaws. Deep down, he was a good person, loyal to his family and friends, and he cared about the businesses and the people within. We interviewed a number of current and prior Roper employees for this project, and they all expressed the same sentiments: they viewed their experience with him as valuable, even life changing. Personally, I miss him, and it’s an honor to share his story.

THE EARLY JELLISON YEARS

Brian Jellison grew up in the small town of Portland, Indiana. His father was the owner of the local hardware store, where he taught his son traditional Midwest values and the importance of education. In his youth, Jellison worked six days a week for his dad, who expected him to put in a full shift when the school day was done. Jellison had to learn how to be fully independent early in his life, as both parents had passed away by the time he was 18. He earned an economics degree at Indiana University and an advanced degree from Columbia University.

After graduating from Columbia, Jellison went through GE’s management training program but spent most of the early to middle part of his career at Ingersoll-Rand, where he was viewed as a smart, very capable leader. While he was considered a bit harsh on his underlings, his financial IQ caught the attention of senior leaders, and by the time Jellison left Ingersoll-Rand in 2001, he had risen to become an EVP and was a candidate for CEO.

Although a high-ranking executive, Jellison was frustrated with Ingersoll-Rand. At that time, the company was intensely bureaucratic. His days were filled with endless meetings, budget planning, and business reviews, and he was surrounded with leaders that always seemed satisfied with mediocrity. Corporate initiatives changed with the wind and were largely ineffective. Time and value were destroyed, and complexity built. Jellison despised these structures common to the industrial world. Even in his final days, Jellison criticized companies such as GE and 3M for their layers of bureaucracy and overly centralized business models. Furthermore, Ingersoll-Rand began shifting its portfolio into more asset-intensive businesses, which Jellison strongly believed to be a mistake.

In those days, large capital equipment was all the rage in industrials. Most were trying to model themselves on GE with big-ticket items like compressors, turbines, and engines—the belief was that the spare parts and service made up for a lower-margin install price and high capital costs. Business schools and management programs focused on concepts like “Porter’s Five Forces” analysis. Big pieces of capital equipment seemed to offer amazing barriers to entry and power over suppliers, and the power in the sales channel grew with each install, even if it meant sacrificing cash terms in order to close an order. At Ingersoll-Rand, Jellison saw firsthand the obsession that leaders had with this business model. GE’s success was so well established at that point that few questioned any of the basic assumptions. Razor/razorblade was the business model everyone wanted to copy, no matter the cost.

By contrast, Jellison saw far higher margin and cash flow characteristics in basic businesses, notably the instrumentation and controls that often sat on top of these pieces of capital equipment. Flying under the radar often meant margins twice what the main suppliers earned, and the overall investment needs were limited and easier to cut back on in recession periods. The factories were smaller, closer to the customer overall, and focused on final assembly. Jellison also saw the big players increasingly interested in larger, splashy M&A deals. Smaller, niche assets (sub-$500 million and even sub-$100 million) garnered more attractive prices. In addition, he saw that smaller company managers were usually more intimate with their businesses overall and respected within their organizations but had not been incentivized appropriately.

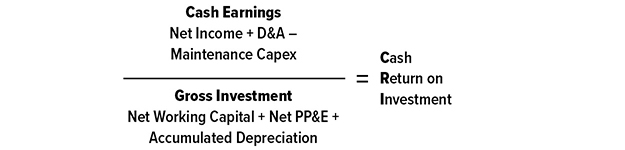

Critical to Jellison’s contrarian view was the mathematical reality that stock market P/E ratios directly correlate to returns on the underlying asset base of the entity, meaning that P/E ratios usually rise as the returns on the underlying assets grow. The very highest P/E multiples are at companies whose business models have few physical assets to maintain and high margins on that low asset base. Companies with low asset intensity and high margins typically generate lots of cash. And companies with these characteristics that also grow are particularly attractive, as each incremental dollar of growth drives returns even higher. This is a concept Jellison called CRI—cash return on investment—and its correlation with valuation was central to his vision. The best example of a high-CRI sector would be software. The best example of a low-CRI sector would be automotive. (See Figure 8.2.)

Figure 8.2: Roper’s CRI metric.

Source: Roper

Jellison vowed that if he ever got a chance to be a CEO, he would do it all very differently. He would squash the bureaucracy, simplify the business model, and focus on compounding the company’s cash flow. But Ingersoll-Rand had become intolerable for Jellison by the time he was 55, and his career overall was at risk of coming to an end—until he got a phone call from a company desperate to fill a job that seemingly few wanted anything to do with. That company was Roper Industries, a small and largely irrelevant, underperforming manufacturer.

THE JELLISON PLAYBOOK

In 2001, the world was all about the internet, the rise of consumer technology, and the visionary leaders from Silicon Valley. Roper was about as far away from that as you could get. It was largely a niche oil and gas supplier with a product line of pumps and test and measurement equipment. Its business was deeply cyclical with near-death experiences every time oil prices went into a down cycle. Jellison ran the pumps business at Ingersoll-Rand, so he was well suited for the job. But Roper was a small company, sub-$600 million in revenues, a big step back in most regards for an executive with a GE and Ingersoll-Rand résumé. Jellison had few other options and viewed Roper as the perfect vessel to build the type of company that he had always wanted, a company virtually the opposite of the two at which he had spent his entire career up to then.

Roper was small, but its niche products delivered high margins overall. Jellison saw promise in the high cash flow characteristics of the business and reinvestment levels that were not overly demanding, but the cyclicality was a problem. Jellison knew that a small company with deeply cyclical assets would struggle to survive the increasingly deeper cycles he worried about (his concerns became a reality when the 2008–2009 financial crisis hit). Even during the smaller but still painful 2001–2002 recession, he saw the risks playing out in real time. He needed to build a more solid foundation for Roper. The company also needed to grow faster than what his inherited portfolio could deliver. The portfolio needed a drastic makeover, and the only way to get there was to do M&A far away from its core. Jellison wanted to focus explicitly on high-margin, high cash flow assets as far away from the oil and gas industry as possible. He wanted asset-light businesses with cash flow that increased over time. This involved substantially higher levels of debt leverage in the process, all of which required approval from Roper’s risk-averse board.

Convincing the board to be aggressive was no easy task. Roper’s legacy board was conservative, and Jellison had not yet been named chairman. His plan was compelling and simple but required a level of change the board struggled with. Many board members flat-out rejected the notion that anything other than smaller bolt-on acquisitions were needed. Several other board members wanted Roper to stick to its core and roll up other pump assets. Beyond the unconventional M&A strategy that Jellison was pitching, he wanted to drive change within the organization itself. He wanted to upgrade management more broadly, run a more decentralized playbook, and change compensation schemes, all of which made the conservative board uncomfortable.

With the high volume of potential M&A targets in the $100 million–$500 million range, Jellison could afford to be picky with his deals. He had three requirements: (1) lower asset intensity than ROP’s existing portfolio, (2) good businesses within niche industries, and (3) excellent management. He would walk away from any deal that lacked all three.

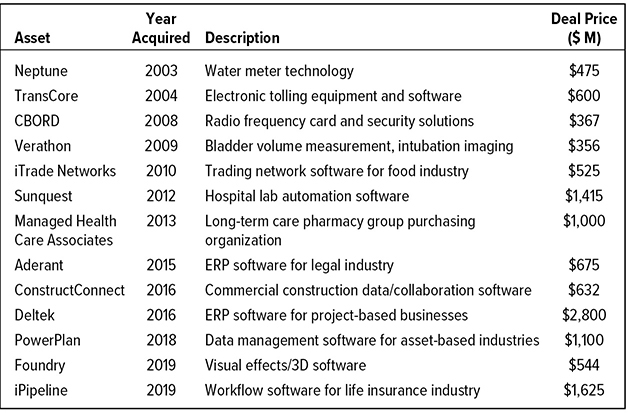

The first asset that made it through this unique diligence filter was Neptune, a well-regarded water meter company. The timing of the deal in 2003 was perfect. Coming out of a deep recession, other potential buyers were hindered by high debt levels and were still licking their wounds from tech-bubble excesses. Jellison loved the asset and saw it as an immediate upgrade from the Roper legacy core. Neptune had a relatively noncyclical water utility customer base and had secular growth from the adoption of automated meter-reading technologies. Margins were high, and customers paid on time if not early; and while factories were needed, it was mostly an assembly-type business with limited heavy equipment or tooling.

Growth had stalled at Neptune, which was the key risk to Roper at the time. Did Roper buy a dud, or would utilities begin to invest again after the recession? The answer came quickly. The growth did materialize, and to this day, water companies continue to change out old meters that require in-person reading with wireless ones that are run off radio frequency identification (RFID). Neptune was a big bet. Its cash flow was three times larger in size than the cash flow Roper was producing—and far larger than what most board members were comfortable with. Had that first deal not been a success from day one, there likely would not have been a second. For Jellison, Neptune was the most important bet of his career. And though he was always comfortable with the math, it paid off well more than anyone had expected.

Just a year later in 2004, and encouraged by the success of Neptune, Jellison closed another game-changing acquisition called TransCore. Better known as the backbone behind much of the US highway electronic tolling system, it uses RFID to read vehicle tags and charge a toll accordingly. It was another high-margin, noncyclical, high-cash-generating asset. At the time, tolling was a limited-growth industry, as the US federal and state gas taxes were more than sufficient to pay for road maintenance. But those funds have become deficient, driving much of the growth in tolling. The deal was another amazing success.

By the end of 2004, less than 2½ years into the job, Jellison had already done $1.5 billion in deals, taking a sub-$600 million revenue company that he inherited in 2001 to one that did $1.5 billion in 2005. He accomplished this while maintaining a minimum 50 percent gross margin threshold with operating margins in the high teens, nearly tripling cash flow from $100 million to $250 million—all while decreasing the asset intensity and volatility of the company overall. (See Figure 8.3.)

Figure 8.3: History of Roper’s major deals.

Source: Roper filings, press reports

The 2004 TransCore deal was Jellison’s first major foray into software, and the success of that deal would influence M&A priorities from then on. At Ingersoll-Rand he ran businesses that required as much as 20 percent working capital as a percentage of sales in order to operate. Those industrial assets required capital investment on top of the daily cash needs: new factories, replacement of old equipment, etc., often adding another 2 to 4 percent of sales, not including what needed to be spent on R&D (3 percent of sales or more) to keep the product cycles moving. That doesn’t even account for hidden expenses that often weigh on traditional manufacturers, including legacy environmental and pension liabilities. Jellison was astounded that those risks were never even considered by most companies when they bought assets. M&A deals were largely valued the same. The valuation for an asset-heavy company with potential tail liabilities was not much less than the valuation for a software company. In fact, if the asset-heavy company had razor/razorblade characteristics, its valuation was often higher.

Jellison saw broad incompetence by M&A market participants. Investment bankers focused pitches on consolidating end markets and making easy-to-do deals where the value was in the synergies, like closing factories and corporate HQs. Boards wanted easy-to-explain combinations, regardless of whether the underlying business itself was good or bad.

He found it insane that a company like GE would sell a high-margin, high-cash asset like NBC Universal for 10x EBITDA (analogous to cash flow), only to turn around and buy capital-intensive and cyclical assets in oil and gas for prices exceeding 12x EBITDA. Capital-intensive semiconductor companies traded for the same valuation as low-capital-intensity software assets. Healthcare equipment was valued as highly as healthcare IT software. It made no sense to him.

Roper was in a position to exploit all those inefficiencies. With his typical deal profile, Jellison could pay off nearly all the debt from a transaction in as little as three years. All cash could go to service that debt, as opposed to building new factories, paying off an environmental liability, or financing a customer. That quick debt paydown allowed for stepped-up dealmaking. With the high-gross-margin profile of his assets, each incremental unit of growth generated outsized profits and cash, but he didn’t need high growth to make his deals work. Jellison was willing to buy mid-growth.

Traditional software companies, like Oracle or Microsoft, generally favored internal new product investment. When they did do acquisitions, they wanted a high-growth profile—certainly above 10 percent, and rarely near the 5 percent ballpark that Roper was more than happy to take. Jellison found the biggest mispricings in less sexy, slower, but still solid growers. These were usually software companies in highly niche markets.

Software was in a different world from that of Roper’s traditional businesses, and critics viewed the company as going down a path it didn’t understand. But Jellison saw it more simply, starting with the basic fundamentals of the software sales cycle. Contracts were typically paid up front with the cash often received before the revenue was even booked, such as in a subscription model. Deferred revenue meant that Jellison could run his company on zero or negative working capital. That entire concept made him almost giddy. There were no factories to invest in, and there was very limited cyclicality to worry about. A large installed base made it harder to get disrupted, at least quickly. And most of these companies weren’t all that well run, meaning Roper could help them to improve operations—in the sales and marketing organization, for example.

Jellison could take that 5 percent unit growth, and through operational improvement, he could translate it into nearly 10 percent profit growth. He then could utilize cash to purchase similar assets that would add another 5 to 10 percent to the top line, translating over time to 15 to 20 percent annualized profit growth. He did this without using equity and maintaining investment-grade debt. Few companies can sustain high-teens profit growth over time. Jellison was in that ballpark most of his 17 years as CEO.

The TransCore deal was the perfect beta test for Roper’s unique M&A and governance models and would be the start of the modern Roper. The lion’s share of transactions after 2004 was centered on high-CRI healthcare and software assets. The valuation spread between these assets and traditional industrial businesses was minimal. If we learn nothing else from the Jellison experience, it’s that valuation mispricings can persist over a very long period of time. Even later in Jellison’s career, he found reasonably priced software assets at valuations not much more than those paid for more asset-intensive businesses. We have seen those spreads widen over the last few years, in some cases exponentially. But for north of 15 years, Jellison was able to capitalize on a marketwide opportunity to invest in niche businesses that few would take the time to consider.

WALL STREET COMES AROUND TO JELLISON’S VISION

Jellison’s early years at Roper coincided with my early years as an industrial analyst, and I have to admit struggling to fully understand his vision. He was good at describing the high-margin, high-cash characteristics of his assets, but he failed to communicate any tangible or repeatable growth algorithm to investors. He explained the CRI concept and his view that as Roper’s returns rose, so would its P/E multiple. The problem, however, was that since each of his acquisitions came with a low asset base, almost by definition, the amount of goodwill created in each deal would be high. Therefore, his returns on a more traditional accounting construct like ROIC would actually go down each time a deal was closed. Then it would begin to rise after the deal, only to be deflated by another deal. For traditional investors, that was a challenge to understand.

To buy into Jellison’s vision, you had to turn traditional accounting frameworks upside down and focus on the returns of the transaction after it closed—the returns earned on each additional dollar of investment. You needed a long-term view, because in the short term the deal would rarely look all that attractive. This was exactly the reason for the mispricing in the first place: deals just looked expensive, both to M&A bankers and to the CEOs and boards they advised.

Jellison’s successes were often explained by critics as luck and pure financial engineering. In hindsight, too many good things happened at Roper over too many years for it to be mere accident. He bought good assets, seemed to run them better than they had ever been run, and developed a consistent growth pattern driven not just by M&A and R&D investments but also by high operating leverage within the assets themselves.

By mid-2004, I was convinced that Roper was doing something very different that deserved more attention. So I begged Jellison for an afternoon of his time and jumped on a plane. I discovered a different Jellison that was a far cry from his distant reputation. He wanted to teach, to mentor. He loved the job, and he loved the game overall, which he viewed as a competition. He wanted to beat the big guys—the GEs, the 3Ms, and the Emersons of the world. An outcast from that world, he was considered not polished enough, with opinions that were too strong. He had a chip on his shoulder. He wanted to win by having a better operating framework, proven by his sector-high margins. He wanted to invest cash at high returns and drive the stock price further up. He benchmarked his company against others, almost to a level of infatuation.

On that hot and sunny afternoon, I saw something unique, something powerful and inspiring. He stood for most of the meeting, writing on a board with multicolored pens. He went soup to nuts on his management philosophy, with increasing energy and fervor. He coached and taught. “This is how you run a company . . . This is how you lead people . . . This is how you grow . . . This is why we are different . . .” The passion was real, and time flew by. For an entire afternoon, I barely said a word. It was one of the greatest days of my business life.

I learned that Jellison wasn’t just a serial buyer of assets; he was a visionary, an exceptional operator, leader, mentor, and person. I flew back to New York and upgraded the stock to Morgan Stanley’s equivalent of a buy, a rating that I kept for 15 years and still maintain today. That stock went straight up nearly every year since then.

ROPER’S GOVERNANCE MODEL

The vast majority of Roper’s acquisitions have been small to mid-sized assets, typically owned by private equity, but too small to IPO and off the radar of larger strategic buyers. Most good acquirers know the danger of overpaying, and overpaying almost always relates to having an overly optimistic deal model around the growth of the asset and the ability of its managers to deliver that result. Jellison’s diligence sessions were skeptical, almost hostile. He wanted to know exactly what he was walking into, well before the deal was even modeled.

One of the lessons from the Danaher chapter is that in the M&A game, a certain amount of information always seems to get held back in diligence by the selling side. So much so that when Danaher closes a deal as the buyer, the first thing it asks is, “What didn’t you tell us?” Common problems could be an unhappy customer, product-quality issues, or a product launch that’s not going as well as reported. Sometimes the issues are very small, but if not fixed fast, they could become a bigger problem down the road. Danaher wants to know the issues as quickly as possible so it can prevent the “down-the-road” part. Danaher deals tend to be large, so there is always some element of surprise. This is just fine, given that much of Danaher’s success comes from the management system it is applying to the asset, which often requires a turnaround.

Roper does smaller deals relatively speaking, does not do turnarounds, and wants no such postdiligence headaches, because when it closes a deal, it backs off and lets the company run as is, with new incentives usually, but with management intact. Roper wants all the pros and cons out on the table, well before it goes down the bidding path. Easier said than done, but Jellison had a way of finding problems up front and walking away from the transaction. This is perhaps why his hit rate was so high. There was extreme process in his diligence.

Although Jellison had an inner circle to assist him, he was hands-on from deal introduction onward. The corporate HQ of Roper has a grand total of about 50 employees, the usual legal, tax, HR, and IR functions and not much else. Jellison didn’t want a big staff of internal dealmakers. The hard diligence, he believed, was with the people themselves, and he felt that only someone at the senior level could have much of a trained eye for management. He needed to be able to ask the tough questions, and that’s the only way he was comfortable doing a deal.

Diligence with the management team was critical, because Roper deals have to include a management team that it could retain. Jellison wanted continuity. He didn’t want the customer experience to change, and he didn’t want the deal itself to be an excuse for leaders to cash out and leave. He wanted the team, and he incentivized the team members to stay and perform to a high standard. But he only wanted assets with A-grade management teams. The deals he turned down through the years were more likely due to management deficiency than the asset quality itself.

While Jellison and his senior team did diligence on management, he would outsource the actual business quality analysis to industry experts, firms such as Bain, McKinsey, or Boston Consulting Group. They may have been more expensive than internal staff, but Jellison wanted an independent view with customer diligence. In his experience, internal M&A folks were biased, wanted to do deals, heard only positive customer opinions, and dismissed the negative data points. And he didn’t believe that Roper had time to do it all. The sale process wasn’t long enough for his team to become experts in every facet of the company, so he paid up to have that analysis done externally.

That doesn’t mean that he ignored the operations. With the company managers and experts in the room together, he asked tough questions. Roper companies often say that they learned more about their businesses after Jellison’s interrogations, particularly because of his focus on a comprehensive value mapping of the product itself. Jellison wanted a detailed breakeven analysis on every product, an analysis that had a shelf life long past diligence.

Once Jellison was comfortable with the management team, product profile, and likely growth algorithm, he could sign off on a deal model that was clear on what price the deal would work at and at what price it wouldn’t. After a transaction closed, we never saw Jellison worry about overpaying, because he knew exactly what he was getting. The Roper process seems to cut down the risk profile to an almost uncanny extent. Of the 50+ deals we observed Jellison do in his 17 years, we can name only a couple that didn’t work out, and those were just modest disappointments.

The risk profile was also lowered, because there was no such thing as “integration risk.” Roper assets are autonomous, never integrated. There are never social or cultural issues, because the existing entity is maintained. There isn’t a mass exodus risk, because managers are locked down before the deal closes. This could be a bigger part of the deal success story than we give it credit.

After a deal closes, Roper focuses on a basic governance model: setting up incentives, doing the relevant benchmarking where it makes sense, and giving the business the tools it needs for success, including a healthy dose of Jellison teachings. Roper executives got paid very well but were expected to deliver results. Jellison demanded excellence and was hard to work for, especially if you were having a tough time growing the profit base. His biggest pet peeve was with underperforming managers who didn’t understand why they were failing. And those who didn’t ask for help when needed. The stars were left alone to perform as they were hired to.

There were a few common problems that Roper saw in its acquired businesses. The first was that high-CRI companies tend to underinvest in sales and marketing and overinvest in the product and in the back office. The high-margin structures helped hide poorly placed jobs. Jellison joked that he saw many companies with more accountants than salespeople, and he would self-fund sales expansion by cutting back-office roles down to the minimum necessary. Many of his assets were so focused on “the product sells itself” concept that they would have only a few sales representatives, who covered only part of the United States. Many of these companies didn’t even attempt to expand outside of large city centers or to think globally. Jellison raised the growth rate just by having more sales coverage.

He also did a lot of educating on the front lines on sales channel management, teaching the importance of increasing hit rates and maximizing existing client coverage. In the world of software, he saw salespeople inadvertently talk clients into postponing purchases because a new product version was coming out in six months. Since new products are often late, that six months could often become 12 months. That delay often ended up driving the customer to a competitor. He wanted sales incentives that maximized the sale of the existing product before anyone was even allowed to see or talk about anything new. He believed selling the current version of the product gave Roper a better chance at upgrades down the road versus “training” the customer to wait for the new product. (See Figures 8.4 and 8.5.)

Figure 8.4: Roper’s revenue increased 9x under Brian Jellison . . .

Source: Roper filings

Figure 8.5: . . . while profits (EBITDA) increased by 14x as the portfolio shifted.

Source: Roper filings

For management teams within Roper, Jellison kept compensation schemes simple. Profit growth was his preferred metric, which made sense given the types of assets in the portfolio. One of the benefits of owning capital-light businesses was that Jellison didn’t have to worry about measuring or paying for returns. As profits grew, returns compounded and profits were equal to or lower than actual cash. He didn’t have to focus on one or the other; they went hand in hand. Jellison wanted simplicity and a common goal line.

One thing he never incentivized for was market share. He didn’t want managers to push bad contracts to gain share. He gladly spent on R&D to develop best-in-class products, but the goal was always about compounding value. Because all his acquisitions were high gross margin and low capital intensity, paying on profit growth meant that managers really had to get only the top-line growth measure right. That was the most powerful lever they could pull. The incentive to grow with and above the market was already there.

POSTMORTEM

Jellison passed away in late 2018, but his legacy is alive and well in the Roper of today. CEO Neil Hunn and CFO Rob Crisci trained diligently under Jellison and use the same simple philosophies that worked for the company for nearly two decades. The concept of CRI may not work for every company or every asset base, but it works for Roper. If nothing else, it enforces discipline around the M&A funnel. High-quality assets that are asset light and generate cash rise to the top. That focus is time-tested, and there is no reason to believe it will change.

Roper is no longer a traditional industrial; yet its past portfolio decisions may not define its future either. Like Danaher, it has gravitated capital to the most attractive areas. Danaher saw the opportunity in healthcare, and Roper in software. But as other areas become more attractive, there is a clear pattern of willingness to adapt. For Roper, it’s CRI that drives its growth focus.

Can Roper grow with this business model forever? Skeptics often say it’s just a publicly traded private equity firm and will run into limits of growth over time. But the comparison to private equity diminishes the operating abilities and the culture of performance that have permeated the organization. There is a willingness at the very top to change, even drastically, if needed. In that spirit, there could be spin-offs and asset sales over time.

Either way, for the lessons in this chapter, what Roper looks like in 5 or 10 years doesn’t really matter. What matters is the mathematical realities that Jellison exploited during his long and successful tenure as Roper’s CEO—realities that form the basis for lessons that somehow get lost over time. At Roper, it’s the simple mathematical realities that matter: rising cash flow, improving already high gross margins, earning a rising return on assets, and gravitating new investment toward better businesses. Rising returns on rising cash flow levels is the holy grail of compounding. It’s not complex, but it requires patience for sure—patience rewarded with tremendous value creation.

Lessons from Roper