11. Printing and Printers

Printing is easy to overlook. Many people dismiss it as a minor subsystem in Linux. I learned that was not the case one Friday. I received an urgent call for assistance from the payroll department. It was payday, and the payroll system was unable to print. Hundreds of people in that company were praying for the printing subsystem to be fixed. In this chapter, we discuss the major types of printer hardware, the major spooler software available, and ways to troubleshoot both.

What Is a Spooler?

Generally speaking, a spooler is a queue for a limited resource. It is a way of throttling and controlling access to these resources. In the long-forgotten dark days of yore, computers were extremely expensive. They were held in big rooms and operated by nice men in sparkling white coats. The peripherals were also expensive. Access to things such as printing, communications, and so on needed to be rationed and controlled. One way to do this is via spooling. Spooling uses a queue to buffer requests for a physical resource. This allows multiple users to leverage use of this scarce physical resource. Spooling also enables devices that communicate at different rates to exchange data (buffering). A spooler allowed for not only job queuing but also prioritization. A spooler also allows for the service to be run by a privileged user and enables queued jobs to run after a user has submitted a request but is no longer accessing the system.

A good example of spooling is the line at the bank. There is a finite number of tellers, and the customers must wait for their turn in a queue. This is an efficient and equitable way to enable access to the scarce resource of tellers.

In this chapter, we discuss troubleshooting the print spoolers used under Linux. The three major spooler types are

• The System V-style spooler

• The Berkeley-style spooler

• CUPS-based spoolers

The concepts could be applied to other print spoolers as well. We discuss the LPRng (a modified Berkeley-style spooler) and CUPS spoolers in depth.

LPRng is a rewrite and extension of the original Berkeley spooler. It also enables System V commands to control the spooler.

CUPS (Common UNIX Printing System) is a new type of spooler. It was designed to work across most UNIX- and Linux-based systems. It is also standards based. It enables printing through RFC1179 (lpr), IPP, CIFS/SMB, Raw socket (JetDirect), and through local printing. CUPS uses network printer browsing and PostScript Printer Description (PPD) files to ease the common tasks of printing.

You can determine which spooler you have by querying your operating system. On RPM-based systems, run rpm -qa | grep -i "cups|lp". This command should return either CUPS or LPRng RPMs. If it returns both, you must confirm which is running (with ps). You can also use chkconfig to confirm which of the two is started on system reboot. On a Debian-based system, you must use dpkg -l to verify which spooler is installed.

Spoolers can be managed through graphical interfaces or from the command line. Generally, the GUI is easier for day-to-day usage, but for troubleshooting, it is best to know how to use the command-line interfaces. We explore them in depth in this chapter.

Print spoolers generally consist of a daemon, spool directories, and a series of configuration files. The daemon accepts the print requests, spools them, monitors the queues, enables changes to print order, cancels print requests, monitors the hardware, formats the print requests, and transfers them to the print device. The spool directories hold the files to be printed until they are formatted and transferred. The configuration files hold the general spooler configuration, printer-specific data, transfer scripts, and so on. The jobs can be sent unformatted (raw) or formatted (cooked). The formatting is generally performed by a Page Description Language (PDL) such as PCL or PostScript.

In some instances, a print queue might not actually be connected to an output device. For example, a print queue can be used to output a PDF file instead of printed paper.

Using the Spooler Commands

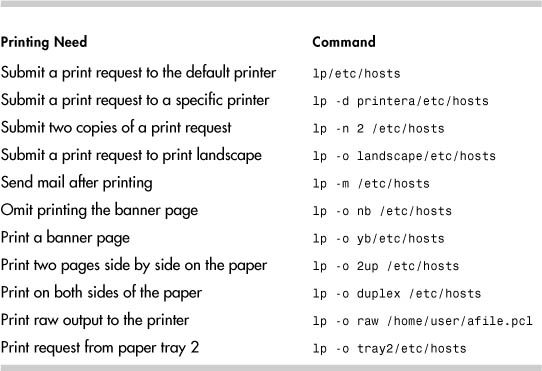

lp is the standard command used by System V-style spoolers to submit print requests. CUPS and LPRng also support lp through emulation. Table 11-1 lists the tasks you can accomplish with various lp commands.

Table 11-1. Various Printing Needs and the Corresponding lp Commands

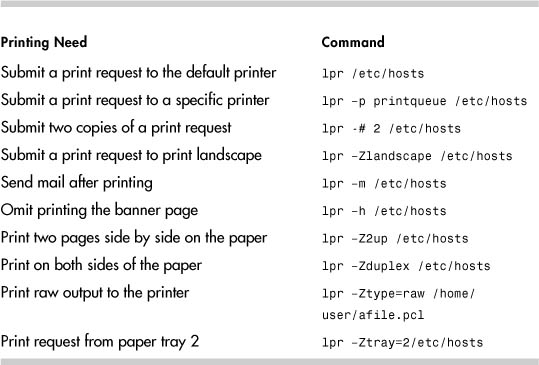

lpr is the standard command used by BSD-style spoolers to submit print requests. CUPS supports lpr through emulation, and LPRng supports it natively. Table 11-2 lists lpr uses and commands.

Table 11-2. Various Printing Needs and the Corresponding lpr Commands

lpadmin is the standard command used by System V-style spoolers to configure printers and classes. It is used in CUPS and System V spoolers. There is no BSD equivalent of lpadmin. With BSD spoolers, you just manually edit the /etc/printcap file. Table 11-3 lists lpadmin uses and commands.

Table 11-3. Various Printing Needs and the Corresponding lpadmin Commands

lpstat is the standard command used by System V-style spoolers to query the status of the spooler, print queues, and jobs.

$ lpstat -t

scheduler is running

system default destination: dj5

device for dj5: usb://hp/deskjet%205550

device for Laser: ipp://localhost/ipp

dj5 accepting requests since Jan 01 00:00

Laser accepting requests since Jan 01 00:00

printer dj5 disabled since Jan 01 00:00 -

Unable to open USB device "usb://hp/deskjet%205550": No such device

printer Laser is idle. enabled since Jan 01 00:00

dj5-1 jtk10 11724800 Fri 21 Jan 2005 10:12:22 PM

EST

lpq is the standard command used by BSD-style spoolers to query the status of the spooler, print queues, and jobs.

$ lpq

dj5 is not ready

Rank Owner Job File(s) Total Size

1st jtk10 1 (stdin) 11724800 bytes

lpoptions is the CUPS command to display or set printer options and defaults. This command is only available in CUPS. For example, you could create two queues for a printer and use lpoptions to set the second queue to print in landscape mode by default.

$ lpoptions

job-sheets=none,none cpi=12 lpi=7 page-bottom=86 page-left=57 page-right=57

page-top=72 scaling=100 wrap=true

$ lpoptions -o scaling=150

[jtk10@sanctus ~]$ lpoptions

job-sheets=none,none cpi=12 lpi=7 page-bottom=86 page-left=57 page-right=57

page-top=72 scaling=150 wrap=true

The options for the print queues are saved in the following locations (from the man page):

~/.lpoptions - user defaults and instances created by non-root users.

/etc/cups/lpoptions - system-wide defaults and instances created by the

root user.

Spooler Plumbing

Think of the spooler as the plumbing in your house and the capability to turn taps on or off as the capability to control job flow to the queues (see Figure 11-1). A main spooler function is the capability to control the flow of jobs through it. It is important to be able to do the following:

• Move a job to another device

• Reject or accept requests from queuing or printing

• Cancel queued requests

• Disable or enable requests to print but still allow them to queue

• Redirect new print requests to another device

Figure 11-1. A simple example that shows the “plumbing” of a System V-style print spooler

The commands used to control the job flow plumbing are:

• lpc—The BSD spooler command that encompasses the functionality of accept, reject, disable, enable, lpmove, and also some functionality of lpstat. CUPS implements a limited subset of this command.

usage: lpc [-Ddebuglevel][-Pprinter][-Shost][-Uusername][-V] [command]

with no command, reads from stdin

-Ddebuglevel - debug level

-Pprinter - printer or printer@host

-Shost - connect to lpd server on host

-Uuser - identify command as coming from user

-V - increase information verbosity

commands:

active (printer[@host]) - check for active server

abort (printer[@host] | all) - stop server

class printer[@host] (class | off) - show/set class printing

disable (printer[@host] | all) - disable queueing

debug (printer[@host] | all) debugparms - set debug level for printer

down (printer[@host] | all) - disable printing and queueing

enable (printer[@host] | all) - enable queueing

hold (printer[@host] | all) (name[@host] | job | all)* - hold job

holdall (printer[@host] | all) - hold all jobs on

kill (printer[@host] | all) - stop and restart server

lpd (printer[@host]) - get LPD PID

lpq (printer[@host] | all) (name[@host] | job | all)* - run lpq

lprm (printer[@host] | all) (name[@host]|host|job| all)* - run lprm

msg printer message text- set status message

move printer (user|jobid)* target - move jobs to new queue

noholdall (printer[@host] | all)- hold all jobs off

printcap(printer[@host] | all) - report printcap values

quit - exit LPC

redirect(printer[@host] | all) (printer@host | off )* - redirect jobs

redo (printer[@host] | all) (name[@host] | job | all)* - redo jobs

release (printer[@host] | all) (name[@host] | job | all)* - release jobs

reread (printer[@host]) - LPD reread database information

start (printer[@host] | all) - start printing

status (printer[@host] | all) - status of printers

stop (printer[@host] | all) - stop printing

topq (printer[@host] | all) (name[@host] | job | all)* - reorder job

up (printer[@host] | all) - enable printing and queueing

diagnostic:

defaultq - show default queue for LPD server

defaults - show default configuration values

client (printer | all) - client config and printcap information

server (printer | all) - server config and printcap

• lprm—The standard command used by BSD-style spoolers to cancel print requests.

$ lpq

dj5 is ready and printing

Rank Owner Job File(s) Total Size

1st jtk10 3 hosts 1024 bytes

2nd jtk10 4 hosts 1024 bytes

[jtk10@sanctus ~]$ lprm 3

[jtk10@sanctus ~]$ lpq

dj5 is ready and printing

Rank Owner Job File(s) Total Size

1st jtk10 4 hosts 1024 bytes

• cancel—The standard command used by System V-style spoolers to remove pending print requests.

• accept—The standard command used by System V-style spoolers to tell a print queue to begin spooling print requests.

• reject—The standard command used by System V-style spoolers to stop spooling print requests.

• disable—The standard command used by System V-style spoolers to stop printing print requests.

• enable—The standard command used by System V-style spoolers to begin printing print requests.

• lpmove—The standard command used by System V-style spoolers to move a print request from one print queue to another.

One key concept is the difference between spooling requests and printing them. The reject command enables you to stop jobs from printing and spooling. If a user tries to print to a queue that is set to reject, the following occurs:

$ reject dj5

$ lpstat -p

printer dj5 disabled since Jan 01 00:00 -

Rejecting Jobs

$ lp -d dj5 /etc/hosts

lp: unable to print file: server-error-not-accepting-jobs

$ accept dj5

The disable command stops jobs from printing, but they still spool up in the queue.

$ accept dj5

$ disable dj5

$ lpstat -p

printer dj5 disabled since Jan 01 00:00 -

Paused

$ lp -d dj5 /etc/hosts

request id is dj5-2 (1 file(s))

$ lpstat -t

scheduler is running

system default destination: dj5

device for dj5: usb://hp/deskjet%205550

device for Laser: ipp://localhost/ipp

dj5 accepting requests since Jan 01 00:00

Laser accepting requests since Jan 01 00:00

printer dj5 disabled since Jan 01 00:00 -

Paused

printer Laser is idle. enabled since Jan 01 00:00

dj5-2 jtk10 1024 Sat 29 Jan 2005 11:31:05 AM EST

$ enable dj5

After the print queue is enabled, the print requests begin printing on the printer.

Term Definitions

It is important to further clarify spooling and printing terms. They are very specific, and using them incorrectly can lead to creating, fixing, or deleting the wrong resource. Let’s take time out for a second and make sure we understand the terminology.

• Queue—A queue is a fancy name for a line. It is the line in which requests wait for a particular resource. A queue can be attached to a printer, a class, or other devices.

• Class—A class is grouping of print queues based on the function of the printers in the class. This grouping could be based on job function (for example, accounting department printers), location, device type (for example, all laser printers), or other classifications.

• Job—A job is another name for a request for a service. It is the smallest unit into which you can break a request.

• User disassociation—Because requests are queued where they can be controlled and printed by the daemon, you can perform other operations on the computer while the printing takes place in the background. By passing the job through a daemon, you can disassociate it from the specific user. The job becomes owned by the daemon’s user instead of the user who submitted it. Usually the submitting user is noted in some control file or log. For example, this process can be performed by passing the request files through a named pipe. The daemon picks up the files on the other side and processes them.

• Abstraction—There are many (sometimes conflicting) definitions of abstraction. It is a programming technique that hides complexity. The best example is the VFS portion of the Linux kernel. VFS is a virtual filesystem layer that sits on top of the filesystem drivers. When using VFS, a programmer doesn’t need to know the intricacies of each driver to work with them.

• Spool directory—This is the directory that stores the files for queued-up jobs. There is either one big directory or a separate directory for each queue or class.

• Print filters—A print filter is a program that inserts control codes for a printer into a document before it is transferred to the printer. An example is inserting the PCL code for landscape output into the beginning of a document to tell the printer to print the page in landscape format. Filters can also be used to translate a job from one printer language to another. For example, a Ghostscript print filter could be used to change an ASCII text file into PostScript.

• Banner or header page—A banner is a page that prints before a print request to delineate jobs and identify the characteristics specific to that job.

• Transfer script (backend)—A script or program used to transfer a print request to a print device. These can be simple transfer programs, or they can have more complex features such as device status checking.

• Footer page—A footer is a page that prints after a print request to delineate jobs and identify the characteristics specific to that job.

• Contention—Depending on the printer type, device contention can be a major issue. With local printers, only one print request can be printed at a time. If two print requests were trying to print on a serial printer at the same time, you would either have interleaved jobs or missing pages. A spooler allows jobs to wait serially for the printer resource to become free. For local printers (serial, USB, parallel), you should define only one queue for each printer. If you have more than one queue for a local printer, the queues can interfere with each other’s print requests. With remote, IPP, and network printing, you can define multiple print queues for each printer because these devices are built to handle requests from multiple systems at the same time.

• Vector vs. raster graphics—Raster graphics are more commonly know as bitmaps. This graphics format assembles the data in a rectangular grid of pixels, each with an assigned color. Common file formats that use raster graphics include GIF, TIFF, BMP, and JPEG, among others. They are generally considered photorealistic, but resizing them can cause jaggedness as the pixel size increases. Most printers are raster-based, so any vector-based graphic is usually translated into a bitmap before printing. Suppose the smiley face in the top-left corner of Figure 11-2 is an RGB bitmap image. When zoomed in, it might look like the big smiley face to the right. Every square represents a pixel. Zoomed in further, we see three pixels whose colors are constructed by adding the values for red, green, and blue.

Figure 11-2. An example of raster graphics

Vector graphics use geometric shapes to build an image. All the images are composed of lines that are defined by a series of mathematical equations. Vector graphics files are generally smaller than raster files. Vector graphics can be resized to almost any size without jaggedness because they are formula-based. Common file formats for vector graphics include PDF, EPS, and others. Plotters can directly print vector graphics. In Figure 11-3, the image on the right is stripped of color and shows the raw geometric shapes. Each shape is represented by a distinct mathematical equation.

Figure 11-3. An example of vector graphics

Printer Types

You can print to many different printer types from your Linux system, and each has its own quirks. The four most common printer classes are

• Dot matrix/line printer

• Laser

• Inkjet

• Plotter

Serial line printers generally accept only ASCII text (these printers are sometimes called dumb printers), but there are exceptions. Some higher-end line printers accept PCL or PostScript. These printers are usually connected through serial or parallel interfaces, but they also can be connected through a terminal server or other network device. Line printers print a page one line at a time. Serial character printers print one character at a time. These printers have tractors that feed the paper through the printer using holes along the sides of the paper. Thus, one of the complications of these printers is paper alignment and jams.

Serial character and line printers accept carbon or duplicate forms, which are commonly used in printing forms, checks, and POS applications. High-speed line printers such as band printers are also used for batched reports from computer systems. They are exceptionally fast and efficient.

One of the great joys of tractor-feed printers is bursting the pages. Because the pages are all connected in a continuous feed, they must be burst apart at their perforations, and the tractor feed holes must be removed from either side.

Laser printers are known for their speed and print quality. These printers print a page at a time rather than a line at a time. They use a heated drum and toner (similar to a copier). Color laser printers are available, but most print in black and white. They can also experience jams in the feeding mechanism, but they occur less frequently than tractor-feed printers. The print quality is generally higher than other printing methods. The printing speed varies depending on the printer but can range from 3 to more than 750 pages per minute.

Most laser printers accept a variety of PDLs. PCL is the generally accepted standard, but PostScript is common on laser printers as well. Fonts and other PDLs can be loaded into many printers with DIMMs inserted into memory slots in the printer. Due to their cost, laser printers are more common in businesses, although the cost has decreased markedly in the last few years.

Laser printers can be printed to by most of the connectivity types depending on the model. The most common is through the network. This method enables many systems to access the printer. It is common to have one laser printer shared in a work area. This approach spreads the cost more efficiently than having one printer per system.

Another big plus of laser printers is the wide range of accessories that can be attached to them, such as sheet feeders and extra trays, duplexers, stackers, collators, mailboxes, and staplers. Although some of these options are available on other printer types, none can match the range and versatility of a laser printer. Other options include pages sizes (8.5 × 11, A4, legal, card stock, envelopes, labels) and different media types such as transparencies.

Inkjets are generally found on individual systems, although they can be shared. They are common for home printing and small office printing because of their capability to print high-quality color pages. They are often used to print color photographs and overheads for presentations. They work by using a fine spray of super-heated ink from a small print head. They can print on a good range of paper sizes and a great range of media including CDs, cloth, transparencies, and many others. Inkjets are usually connected locally to a computer through USB or parallel interfaces.

Plotters are very high-end print devices that use a pen to essentially draw the image on the paper. Older plotters could only print line-based vector graphics. The newest generations of plotters have switched to other technologies such as thermal inkjet printing. These are usually used in CAD/CAM/CAE environments for schematics and blueprints or for large-format printing. The newest plotters offer exceptionally high quality and can print photo-quality raster graphics on large rolls of paper (60-inch-wide rolls, for example). Plotters are usually either USB, parallel, or networked.

There are many other types of printers such as solid ink, electron beam, thermal wax transfer, electrostatic transfer, and dye sublimation that we do not cover here.

Connectivity Types

To understand printing and troubleshoot it, you need to know details about the various methods of connectivity to printers. Without this information, any problems specific to a connectivity method are a mysterious black box.

Local Serial Printing

Serial communication (through RS-232) is often used for terminals, modems, and other data communication devices. It is flexible and solid but relatively slow. Serial printing is one of the older printing methods, but it gives us a great chance to discuss in depth how local printing works. You can use RS-232 reliably with a cable up to about 15 meters (about 50 feet). This length depends on the quality of the cable, the amount of electromagnetic interference, and the baud rate (speed) at which you are communicating. The slower you communicate, the more reliable the data transmission. 9600 seems to be the best combination of reliability and speed for longer cables, but you can drop to 2400 or 1200 if needed.

Serial ports can communicate to both DTE (data terminal equipment) and DCE (data circuit equipment) devices. DTEs are devices where data terminates such as a printer, terminal, PC, and so on. DCEs are devices that transmit data such as modems, CSUs, DSUs, and so on. This distinction is important because the primary problem with any serial communication is getting the right cable. Without the correct cabling, serial printing does not work. Cable quality is also an issue. Don’t just pick up a cable out of a box in a storage room and assume it will work correctly.

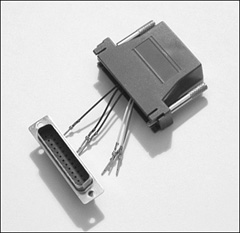

There are many types of cables, and each has a different pinout. The pins are the wires over which electrical signals travel. The pinout is the map that shows which pins on one end of the cable map to which pins on the other end. There are three main types of serial connection. They are DB-25 (25 pins), DB-9 (9 pins), and RJ-45 (8 pins, which is essentially a 4-pair network cable). A cable hood for DB-25 and DB-9 can either be male or female. Examples of male and female connectors are shown in Figures 11-4 and 11-5. Male hoods have the pins sticking out, and female hoods have holes to accept the male pins. Typically, cables have one male and one female end.

Figure 11-4. A male DB-9 serial connector

Figure 11-5. A female DB-9 serial connection

There are usually at least three active pins in a serial cable. They are Rx (receive), Tx (transmit), and Gnd (ground). An example pinout is shown in Figure 11-6. In a DB-9 connector, DCE devices use pin 2 for Rx, pin 3 for Tx, and pin 5 for Gnd, and DTE devices use pin 3 for Rx, pin 2 for Tx, and pin 5 for Gnd.

Figure 11-6. Simple DB-9 DCE to DB-9 DTE pinout

The serial device receiving the data uses flow control to let the sending device know that it has received all the data it can handle (for example, in a print buffer on a printer). This functionality is needed because a computer can send a print request faster than the printer can print it. The job is stored in buffer memory on the printer while it is printing. If the print job is bigger than the buffer, the printer needs to be able to tell the computer to stop sending more characters until it has freed space in the buffer.

Serial printers usually use either hardware flow control (RTS/CTS) or software-based flow control (XON/XOFF). There are pins on a serial connection that can be used for hardware data flow control when printing such as RTS (request to send) or CTS (clear to send). When the receiving device is ready to accept data, it raises (sends an electric signal on) its RTS pin. This signal comes across to the other end of the cable on the CTS pin and indicates that it is ok to transmit data. If the print buffer in the printer fills up, the printer drops the CTS signal, and the computer holds additional data until the CTS is raised again. Figure 11-7 shows how the pins connect to the wires when the housing is opened.

Figure 11-7. A serial connector dismantled

We will not discuss the other pins not commonly used in printing such as CD (carrier detect), DSR (dataset ready), DTR (data terminal ready), and others.

To communicate with a local serial printer, you use a device file. An example of a serial device file is the following:

crw-rw---- 1 root uucp 4, 64 Jan 2 07:31 ttyS0

You can get information about a serial port by using the setserial command:

# setserial /dev/ttyS0

/dev/ttyS0, UART: 16550A, Port: 0x03f8, IRQ: 4

You can gather additional settings data about a serial port by using the sty command. The stty command enables you to print and manipulate serial line settings such as speed, the bit setting, parity, character translation, number of columns, and so on. Here is an example output from stty that reports all the current settings on a serial port:

# stty -F /dev/ttyS0 -a

speed 9600 baud; rows 0; columns 0; line = 0;

intr = ^C; quit = ^; erase = ^?; kill = ^U; eof = ^D; eol = <undef>;

eol2 = <undef>; start = ^Q; stop = ^S; susp = ^Z; rprnt = ^R; werase = ^W;

lnext = ^V; flush = ^O; min = 1; time = 0;

-parenb -parodd cs8 hupcl -cstopb cread clocal -crtscts

-ignbrk -brkint -ignpar -parmrk -inpck -istrip -inlcr -igncr icrnl ixon

-ixoff

-iuclc -ixany -imaxbel

opost -olcuc -ocrnl onlcr -onocr -onlret -ofill -ofdel nl0 cr0 tab0 bs0

vt0 ff0

isig icanon iexten echo echoe echok -echonl -noflsh -xcase -tostop -echoprt

echoctl echoke

If the printer is connected and set up correctly, you should be able to send a file using cat to the device, and it should come out on the printer. It may look funny because of formatting or line feed issues.

# cat afile > /dev/ttyS0

This command opens the serial port and transmits the data across the transmit pin to the printer. The printer then takes the data and prints it. However, the data might be stair-stepped, which looks like this:

See Dick run.

See Jane run.

See Dick and Jane run.

This error happens because of a mismatch in end of line characters. In Linux and UNIX, the end of line is signaled in text streams by a line feed (LF). You will sometimes also see this notated with a

character. With DOS, Windows, and other systems, an end of line comprises a carriage return and a line feed (CR/LF). If you look at the stty options, you can see that the onlcr option specifies whether an LF should be changed into CR/LF. To set the onlcr flag, run this command:

# stty -F /dev/ttyS0 onlcr

To unset the onlcr flag, use:

# stty -F /dev/ttyS0 -onlcr

To set a baud rate for a serial line to 9600 baud, issue the following command:

# stty -F /dev/ttyS0 9600

Flow control is primarily an issue with slower printers and longer cables. Flow control problems can cause characters or strings of characters to be dropped in job. The characters can be dropped from the middle or end of the job. This problem can be addressed in three ways. The first solution is to slow the baud rate over the serial line. This solution is imperfect, but it works well in a lot of cases. Second, you can switch the printer from software flow control to hardware flow control. The signaling on hardware flow control is more precise, so timing issues and missed signals are less likely. Last, you can adjust the closing_wait setting on the serial port with the set_serial command. This option is volatile, meaning that it only lasts until the next reboot. The way around this issue is to place the set_serial command in an rc script such as /etc/rc.serial. This method changes the amount of time after close before the serial port buffer is flushed. The default time is 30 seconds. If you don’t have a copy of rc.serial, look for a template under /usr/share/doc/setserial*/rc.serial.

These and other settings can usually be controlled from the spooler’s configuration files or rc files. We discuss this subject in further detail in the sections on each spooler type.

Local USB Printing

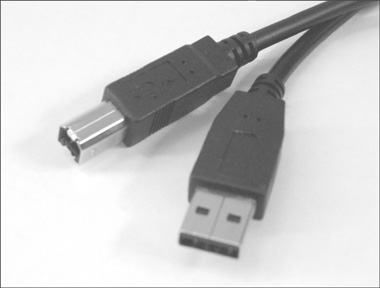

USB has quickly become the default for attaching peripherals to a computer. It is easy to use and fast. It has supplanted parallel (ISEE 1284) as the default method for printing. Most inkjet printers come with at least one USB port. Some have both USB and parallel ports. There are two current standards for USB devices. USB 1.1 runs at 12Mbps, and USB 2.0 runs at 480Mbps. Both standards accept up to 127 peripherals per bus. USB also supports Plug-and-Play installation and hot plugging. The maximum length for a USB cable according to the standard is 16 feet. USB devices can either draw power from the USB bus or be externally powered. This choice depends on the power needs of the device.

There are two types of connectors on a USB cable. They are referred to as type A and type B connectors. The connectors can either be mini- or standard-sized. The type A connector is male and plugs into the female port on the computer. The type B connector is male and connects into the peripheral. You can see examples of connectors in Figure 11-8.

Figure 11-8. Standard-sized type A and type B USB connectors

To effectively use USB printing, you should have at least a 2.4 kernel. To use USB 2.0, you should have a late 2.4 or 2.6 kernel. The USB printers use device files similar to /dev/usb/lp0. The last digit increments with each printer added.

Non-CUPS spoolers can be confused by the printer device files because USB device files are assigned and removed dynamically. If they are powered on or detected in different orders, the device files could reverse, which could cause print requests to go to the wrong printer. CUPS uses a USB abstraction layer and the printer’s manufacturer, model, and printer serial number to send the print job to the correct printer.

To gather more information about what USB devices are attached to a system, you can run the following command:

# lspci –v

00:10.0 USB Controller: VIA Technologies, Inc. VT82xxxxx

UHCI USB 1.1 Controller

(rev 80) (prog-if 00 [UHCI])

Subsystem: Micro-Star International Co., Ltd.: Unknown device 3902

Flags: bus master, medium devsel, latency 32, IRQ 11

I/O ports at d800 [size=32]

Capabilities: [80] Power Management version 2

00:10.1 USB Controller: VIA Technologies, Inc. VT82xxxxx

UHCI USB 1.1 Controller

(rev 80) (prog-if 00 [UHCI])

Subsystem: Micro-Star International Co., Ltd.: Unknown device 3902

Flags: bus master, medium devsel, latency 32, IRQ 3

I/O ports at dc00 [size=32]

Capabilities: [80] Power Management version 2

00:10.2 USB Controller: VIA Technologies, Inc. VT82xxxxx

UHCI USB 1.1 Controller

(rev 80) (prog-if 00 [UHCI])

Subsystem: Micro-Star International Co., Ltd.: Unknown device 3902

Flags: bus master, medium devsel, latency 32, IRQ 10

I/O ports at e000 [size=32]

Capabilities: [80] Power Management version 2

00:10.3 USB Controller: VIA Technologies, Inc. USB 2.0 (rev 82) (prog-if

20 [EHC

I])

Subsystem: Micro-Star International Co., Ltd.: Unknown device 3902

Flags: bus master, medium devsel, latency 32, IRQ 5

Memory at ea001000 (32-bit, non-prefetchable) [size=256]

Capabilities: [80] Power Management version 2

And then:

# cat /proc/bus/usb/devices

T: Bus=04 Lev=00 Prnt=00 Port=00 Cnt=00 Dev#= 1 Spd=12 MxCh= 2

B: Alloc= 0/900 us ( 0%), #Int= 0, #Iso= 0

D: Ver= 1.10 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=00 MxPS= 8 #Cfgs= 1

P: Vendor=0000 ProdID=0000 Rev= 2.06

S: Manufacturer=Linux 2.6.9-1.681_FC3 uhci_hcd

S: Product=UHCI Host Controller

S: SerialNumber=0000:00:10.2

C:* #Ifs= 1 Cfg#= 1 Atr=c0 MxPwr= 0mA

I: If#= 0 Alt= 0 #EPs= 1 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=00 Driver=hub

E: Ad=81(I) Atr=03(Int.) MxPS= 2 Ivl=255ms

T: Bus=03 Lev=00 Prnt=00 Port=00 Cnt=00 Dev#= 1 Spd=12 MxCh= 2

B: Alloc= 0/900 us ( 0%), #Int= 0, #Iso= 0

D: Ver= 1.10 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=00 MxPS= 8 #Cfgs= 1

P: Vendor=0000 ProdID=0000 Rev= 2.06

S: Manufacturer=Linux 2.6.9-1.681_FC3 uhci_hcd

S: Product=UHCI Host Controller

S: SerialNumber=0000:00:10.1

C:* #Ifs= 1 Cfg#= 1 Atr=c0 MxPwr= 0mA

I: If#= 0 Alt= 0 #EPs= 1 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=00 Driver=hub

E: Ad=81(I) Atr=03(Int.) MxPS= 2 Ivl=255ms

T: Bus=02 Lev=00 Prnt=00 Port=00 Cnt=00 Dev#= 1 Spd=12 MxCh= 2

B: Alloc= 0/900 us ( 0%), #Int= 0, #Iso= 0

D: Ver= 1.10 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=00 MxPS= 8 #Cfgs= 1

P: Vendor=0000 ProdID=0000 Rev= 2.06

S: Manufacturer=Linux 2.6.9-1.681_FC3 uhci_hcd

S: Product=UHCI Host Controller

S: SerialNumber=0000:00:10.0

C:* #Ifs= 1 Cfg#= 1 Atr=c0 MxPwr= 0mA

I: If#= 0 Alt= 0 #EPs= 1 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=00 Driver=hub

E: Ad=81(I) Atr=03(Int.) MxPS= 2 Ivl=255ms

T: Bus=01 Lev=00 Prnt=00 Port=00 Cnt=00 Dev#= 1 Spd=480 MxCh= 6

B: Alloc= 0/800 us ( 0%), #Int= 0, #Iso= 0

D: Ver= 2.00 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=01 MxPS= 8 #Cfgs= 1

P: Vendor=0000 ProdID=0000 Rev= 2.06

S: Manufacturer=Linux 2.6.9-1.681_FC3 ehci_hcd

S: Product=EHCI Host Controller

S: SerialNumber=0000:00:10.3

C:* #Ifs= 1 Cfg#= 1 Atr=e0 MxPwr= 0mA

I: If#= 0 Alt= 0 #EPs= 1 Cls=09(hub ) Sub=00 Prot=00 Driver=hub

E: Ad=81(I) Atr=03(Int.) MxPS= 2 Ivl=256ms

You can see that devices that have Spd=12 are USB 1.x and Spd=480 are USB 2.0.

Local Parallel Printing

The IEEE 1284 standard is bidirectional, but Linux drivers are write-only. This means you receive no status or error information from the printer.

Centronics is the de facto standard for parallel cabling. It has a 36-pin hood to connect to the printer and a 25-pin connector to plug into the computer’s parallel port.

When the new kernel is booted, the printer should be identified automatically. To check, you can run:

cat /proc/sys/dev/parport/parport0/autoprobe

# dmesg |grep –i lp

The device file is of the format /dev/lp0. The last number of the device file increments for each device on a parallel port.

Parallel ports can be configured as Standard Parallel Port (SPP), Bidirectional Parallel Port (BPP), Enhanced Parallel Port (EPP), or Enhanced Capabilities Port (ECP). EPP and ECP are the most common on modern computers. They are extensions on Centronics and SPP. EPP and ECP are much faster than the original Centronic/SPP standard and have improved handshaking and flow control. The mode is generally set in the computers BIOS. The best setting is a combination of EPP/ECP (if it is offered). If EPP/ECC is not available, you can try to fall back to ECP.

Several versions of EPP are available. If possible, you should select EPP 1.9. This selection sometimes requires experimentation, though. If you are still having problems, you might also try SPP and see how that works for you. Because the Linux driver is not bidirectional, you only lose the speed and handshaking advantages of the other modes.

As with RS-232, parallel printing is extremely sensitive to cabling issues. Make sure the cable is a good-quality IEEE 1294 cable. Also try to minimize the cable length. It is possible to make parallel printing work up to 50 meters, but it becomes problematic past 15 meters.

Remote Printing

Remote printing over port 515 is based on the computing standard RFC1179 created by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). RFC stands for Request For Comment. This method is how a proposed standard is documented and published to the Internet community for feedback. These standards form the communication protocols that make up the Internet (such as HTTP). RFC1179 and other RFCs are available from http://www.ietf.org/rfc. The technology specified by RFC1179 can be used for printing to another system’s spooler. This functionality enables you to print remotely to printers that are locally attached to another system. The other system could be a terminal server, a print server, or a computer.

It is important to understand what format is used for RFC1179 printing. The RFC states the following:

3.1 Message formats

LPR is a TCP-based protocol. The port on which a line printer daemon listens is 515. The source port must be in the range 721 to 731, inclusive. A line printer daemon responds to commands sent to its port. All commands begin with a single octet code, which is a binary number which represents the requested function. The code is immediately followed by the ASCII name of the printer queue name on which the function is to be performed. If there are other operands to the command, they are separated from the printer queue name with white space (ASCII space, horizontal tab, vertical tab, and form feed). The end of the command is indicated with an ASCII line feed character.

One disadvantage to RFC1179-style printing is that many of the command-line options are not passed between the two systems. The options passed are very limited. For example, the landscape option would not be passed.

The spooler sends two files for each remote print request. The first is a control file, and the second is a data file. The files can be sent in any order to the remote spooler.

The control file contains information about the print request (such as user ID, queue name, and so on). The control filename is in the format cfAzzzhostname, where the zzz is a three-digit job number and hostname is the hostname of the sending system. These files are stored in the spooler’s temporary directories. The print request transfer begins by sending a control string to the remote spooler. This is generally one of three strings. The first is an abort string. The second lets the spooler know that a control file is being transferred, and the last lets the spooler know that a data file is being sent.

The control file contains multiple lines of data. Each line is a separate parameter. The first character of each line is a command character followed by the variable data.

RFC1179 also provides for requesting the status of a print queue, limited control over changing queue status, and canceling a print request.

Control Files

A typical control file contains the following data:

Hhost.domain.tld

J/home/usera/afile /home/usera/bfile

CA

Lusera

Pusera

fdfA003host.domain.tld

N/home/usera/afile

UdfA003host.domain.tld

fdfB003host.domain.tld

N/home/usera/bfile

UdfB003host.domain.tld

This is not gibberish. All it takes is the secret decoder ring. It is a series of commands to the remote spooler. Each line is executed one after another. In this example, usera on system host.domain.tld has printed two files (/home/usera/afile and /home/usera/bfile).

• Hhost.domain.tld—H is the key for the hostname. The hostname in this case is host.domain.tld.

• J/home/usera/afile /home/usera/bfile—J is the key for job name. The default value is a list of filenames printed. It is possible to specify a job name with lpr -J jobname or lp -t jobname. The files submitted for printing are /usera/afile and /home/usera/bfile.

• CA—C is the key for printer class. You can specify a class through lpr -C class.

• Lusera—L is the key for banner page. The user name can be omitted. Without this, a banner page will be suppressed. Some printers or spoolers create their own banner pages and ignore this flag.

• Pusera—P is the key for the user name to be printed on the banner page. The default is the user who submitted the request. It can also be specified through lpr -U username or lp -u username. The user name in this case is usera.

• fdfA003host.domain.tld—f is the key for print formatted file. The filename in this case is the first data file: dfB003host.domain.tld.

• N/home/usera/afile—N is the key for the name of the source file. The filename in this case is /home/usera/afile.

• UdfB003host.domain.tld—U is the key for unlink data file. This command causes the temporary data file to be removed from the spooler directories.

The f, N, and U commands are repeated again for the second file.

There are many other possible control characters in a control file. They are all defined in RFC1179. Also be aware that some spoolers also add their own proprietary extensions to the control file. These are used when printing between two spoolers of the same type.

Data Files

The data file contains the file or text stream that was submitted to be printed. Data is usually submitted by specifying a file to be printed or by redirecting STDIN to the print command. The data filename is in the format dfAzzzhostname, where the zzz is a three-digit job number and hostname is the hostname of the sending system. There can be more than one data file if more than one were submitted to be printed in one job.

After the control and data files are transferred, the remote spooler should return a status code. For example, �00 indicates success. Anything else indicates an error.

Contention

How does remote printing handle contention? The jobs are accepted and spooled to the remote print queue. There, the jobs wait in the queue until it is their turn to print on the printer.

Troubleshooting Tools

Remote printing troubleshooting tools include the following:

• Logs in /var/log such as the syslog can contain network errors.

• tcpdump of traffic to port 515 enables you to monitor the packets in and out of a system if you think they are being mangled.

• nmap can be used to verify that port 515 is open and accepting connections.

Scenario 11-1: Unable to Print to Remote Printer

A user received the following error:

$ lpr /home/user/Billy.txt

$ lpq

could not talk to print service at germany

To troubleshoot this situation, you would do something like the following:

- Confirm that local and remote queue names are correct. The network is shown in Figure 11-9.

In this example, a local serial print queue (Berlin) is defined on the host Germany. If the administrator of the host France wants to print through remote printing, he needs to add it. To do this, he must define four pieces of information in his spooler:

• Remote host name (Germany in this case)

• Remote queue name (Berlin in this case)

• Remote port (515 by default)

• Local queue name (Paris in this case)

The local queue name on France could be Berlin as well, or something else. In this example, the administrator defined it as Paris. The administrator on England might also add the printer with the following values:

• Remote host name (France)

• Remote queue name (Paris)

• Remote port (515)

• Local queue name (London)

As you can see, a print request submitted to London would then go to Paris and then would be forwarded to Berlin for printing. This might happen if France were a print server. You could also define the printer on England to print directly to Germany.

- Confirm that the server print daemon is accepting connections on port 515 from the client. You would expect to see the following:

# telnet germany 515

Trying 127.0.0.1...

Connected to germany.

Escape character is '^]'.An error might look like this:

$ telnet 192.168.2.55 515

Connecting To 192.168.2.55...

Could not open connection to the host, on port 515:

Connect failed - Confirm that outbound connections are allowed from the client on ports 721–731. Some systems have firewalls that restrict connections. You can verify this by looking at the firewall configuration. Run

iptables -Loripchains -L(for an older firewall) to list the firewall configuration. - Confirm that the entry in

/etc/servicesfor the service is correct.cat /etc/services |grep 515

printer 515/tcp spooler # line printer spooler

printer 515/udp spooler # line printer spooler - Confirm that the remote spooler (on Germany) can print locally.

Log into Germany and print a file to Berlin. If this works, we know that the local spooler on Germany is working correctly.

Other possible causes of this type of error include the following:

• The remote spooler is not RFC1179 compliant.

• The hostname is longer than eight characters, which can sometimes cause problems.

• Job numbering is above 9999, which can also cause problems with some spoolers.

Raw Network Socket Printing

This type of printing was pioneered by Hewlett-Packard, but most printers with network connections support raw network printing. The main port for these transfers is port 9100, but on multiport print servers, it is also possible to send print jobs to ports 9101 and 9102. This is called raw printing because the port is opened and the raw text stream is then transferred to the device. There is no queue or spooler on the other end to receive the print request. Any formatting or other control characters must be embedded into the raw text stream. The network device can also send back status or error messages while the connection is open. The connection is kept open until the request finishes transferring.

Note

Microsoft calls this Standard TCP/IP port printing.

These print servers can be cards inside the printer that allow connection to the network or external boxes with ports to connect the printer to a network connection. Just to confuse things further, many networked printers support printing to both ports 515 and 9100. For example, Hewlett-Packard JetDirect print servers also accept RFC1179 print requests to the queues raw and text.

One important question is: “How does the print device obtain its IP address and netmask?” Most network printers can obtain their configuration in several ways. The configuration can be hard coded through the front panel or a network interface (TELNET or HTTP), or dynamically through DHCP and bootp. Bootp and DHCP (which is newer and more capable) both are used to dynamically assign networking information to network devices.

The vast majority of printing through port 9100 is done to print servers, but it is possible to set up a UNIX or Linux system to accept print requests this way. This is done by adding a new service line to /etc/inetd.conf. Two examples of this are

• Directing the input to the spooler:

9100 stream tcp nowait lp /usr/bin/lp lp -d queuename

• Redirecting the raw data stream to a device:

9100 stream tcp nowait lp /bin/dd dd of=/dev/lp0

Contention

How does a print server such as HP’s JetDirect handle device contention? They are relatively simple devices and have no spooler. They just have a print buffer. When the print device is busy printing, all the other hosts must retry until the print server is free.

Troubleshooting Tools

Troubleshooting tools for working on raw network socket printing problems include the following:

• Netcat (nc):

cat <filename> | nc -w 1 <host> <port>

This command transfers a file to the network printer and bypasses the spooler. If this works, you have device connectivity, and the problem is with the spooler.

• TELNET to port 9100:

telnet hostname 9100

If you receive a connection on this port, then the printer is online and is accepting connections.

• Syslog: Check syslog for errors

IPP

“The Internet Printing Protocol (IPP) is an application level protocol that can be used for distributed printing using Internet tools and technologies.”

[RFC2911]

IPP is a new client/server print protocol that was designed in cooperation with the IETF. IPP is designed with networks and shared resources in mind. All printer and job objects are defined using a Uniform Resource Locator (URL), just like what is used for other Internet-based services such as HTTP, FTP, and so on. Unlike other protocols, IPP also supports access controls, Basic, Digest, and Certificate authentication, LDAP integration, and SSL and TLS encryption. Many new network printers and print servers include built-in IPP capabilities.

The IPP standard is defined in the following documents from the IETF:

• Design Goals for an Internet Printing Protocol [RFC2567]

• Mapping Between LPD and IPP Protocols [RFC2569]

• Rationale for the Structure of the Model and Protocol for the Internet Printing Protocol [RFC2568]

• Internet Printing Protocol/1.1: Encoding and Transport [RFC2910]

• Internet Printing Protocol/1.1:Model and Semantics [RFC2911]

• Internet Printing Protocol/1.1: Implementer’s Guide [IPP-IIG]

Five key terms are needed to understand IPP. They are IPP printer, IPP client, privileged operator, job, and notification service. IPP can use port 631 or port 80. Port 631 is the most commonly used. Here is an example of a URL for an IPP print device:

# lpstat –v Laser

device for Laser: ipp://localhost/ipp

IPP uses standard HTTP POST and GET commands to enable bidirectional communication with print devices. It uses a special “application/ipp” MIME Content-Type. IPP allows normal push printing, but it also has the capability to perform pull printing, in which a server or printer is told the URL of a document, which is then pulled from that URL and printed.

The IPP RFC breaks down the capabilities of IPP printing into six categories:

• Finding a printer

• Creating a local instance of the printer

• Viewing the printer status and capabilities

• Submitting a print job

• Viewing print status

• Altering the print job

Next is an example of a POST-based communication with an IPP device.

POST /ipp/ HTTP/1.1

Content-Length: 285

Content-Type: application/ipp

Host: 192.168.2.33

Terminal Servers (Networked Serial)

A terminal server (see Figure 11-10) is a piece of networked hardware that provides multiple users with access to terminal and console ports, modems, printers, and other serial devices. A terminal server can be either a piece of custom hardware or a standard computer system with a large number of serial ports. In either case, a terminal server provides a way to enable hardware to be accessed from multiple systems, and it provides network access to devices that don’t ordinarily have it. There are two main ways to access devices connected to terminal servers. The first is a direct network connection through specific ports. The other is to use drivers on the client to packetize communication to local device files and forward it to the terminal server. Configuration varies between terminal server manufacturers.

Figure 11-10. A terminal server

Page Description Languages

A Page Description Language (PDL) is a series of commands used for controlling printed page layout. Think of a PDL as a markup language like HTML. A PDL is a series of commands and escape sequences that are embedded into the print data.

A Printer Job Language (PJL) controls job separation, changing and reporting the printer status, changing of printer settings, and PDL language changing between jobs. PJL acts as a wrapper around the PDL(s).

Several examples of PDLs are shown in the following list:

• PostScript—PostScript was developed by Adobe. It is a tagged markup language that is rendered into raster by the print driver, filter script, or printer hardware.

• PCL—PCL was developed by Hewlett-Packard. It is also a tagged language. It uses escape sequences.

• HP/GL—HP/GL was developed by Hewlett-Packard. It is the industry standard PDL for plotters.

• Other formats—Raw graphics such as TIFF and JPEG can be interpreted by some printers.

General Printing Troubleshooting

There are many troubleshooting techniques that are useful no matter which spooler you are using. These techniques enable you to understand the printing environment and the general points of failure. When you know these pieces of data, you can use the troubleshooting tools specific to each spooler to figure out what is causing the failure.

Mapping the Spooling Environment

This technique might be the least often used, but in many cases, it can be the most useful. Figure 11-11 shows an example of a map. It is best to have a map completed before printing problems occur so that you can refer to it when troubleshooting.

Figure 11-11. An example of mapping the spooling environment

Figure 11-11 shows multiple types of printers and their connection methods. Keep in mind that a printer that might be local to one system could also be configured as a remote printer on another system. You must know not only the absolute location of a device but also its relationship to other devices. It is best to have this map completed and maintained before you have printing problems because it enables you to immediately understand the host/printer relationships instead of having to figure them out under duress. If you are not sure about the specifics of a printer’s configuration (such as an IP address), you can always go to the printer and attempt to print a test or configuration page from the printer’s front panel.

Breakpoints

The common breakpoints for printing are listed here:

- Can other systems print to the printer?

- Can you print to the printer by bypassing the spooler?

- What do you find when you put the spooler in verbose or debug mode and look at log file entries?

- What is the scope of the problem?

A. Can’t print to one printer?

B. Can’t print to several printers?

a. Cannot print to a specific class or type?

b. Cannot print to printers in a specific location?

c. Cannot print to printers with a network device or server in common?

d. Cannot print to all printers?

The answers to these questions will direct you to the area you will need to troubleshoot further.

Summary

By breaking printing into its component parts, it is relatively easy to troubleshoot. Without knowledge of spooler types, printer connection types, printer types, and so on, printing problems are difficult to fix. It is important to remember to map your environment, be specific about connection types, and test breakpoints to find where the problem lies.