CHAPTER OUTLINE

Connecting Authenticity and Trust

Building Trust Through Authenticity

Maintain Openness

Clarify and Focus Work

Display Scrupulous Fairness

Implications for Manager Performance

Executing Tasks

Developing People

Delivering the Deal

Energizing Change

Everything in the universe is interconnected. We know this because Douglas Adams, author of books about how to find your way around the universe, said so. Or more precisely, Dirk Gently, the main character in Adams's book Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency, said so. Dirk is a private detective who uses telekinesis, quantum mechanics, and trips to the Bahamas to solve cases and, in the process, save the human race from extinction. His understanding of what he calls "the fundamental interconnectedness of all things" makes his detection approach holistic in the largest possible way.[284]

We too have a sense of interconnectedness, and we didn't need to go to the Bahamas to get it. Take authenticity and trust, for example. Integrity is a main pillar of authenticity. Integrity means adhering consistently to a code of high moral ethics and behavior. Consistency, in turn, forms a core element of trust. We think of authenticity and trust as sequential and complementary elements that add power to our manager performance model. In the architecture of our model, they form the foundation, the basis for strength and stability.

Trust is defined as the willingness of one individual to make himself or herself vulnerable to another. The acceptance of vulnerability must be grounded in the expectation that the trustee will act in a predictable way that benefits, or at least doesn't harm, the person granting trust. People are willing to trust one another when they have confidence in what the individual can do (ability to confer a benefit on the trustor) and what the individual will do (predictable inclination to exercise that ability).[285] Trust thus has both a cognitive aspect (experience tells me that I can predict how this person will act) and an emotional aspect (our relationship provides a foundation for the beneficial behavior I expect to receive).[286] But trust is also paradoxical. Belief in another's trustworthiness precedes trust, but trustworthiness can't be proven unless trust is first given.

Of all the elements in our manager performance model, none has a more dramatic effect on a manager's ability to work effectively offstage than reciprocal trust. If employees don't trust the people with whom they transact their business, then transactions will be few, meager, and unfulfilling. Conversely, managers who foster trust, and who do all the other things we've described to make individuals and groups effective, create the environment for individual and group success. Peter Drucker put it this way: "The leaders who work most effectively, it seems to me, never say 'I.' And that's not because they have trained themselves not to say 'I.' They don't think 'I.' They think 'we'; they think 'team.' They understand their job to be to make the team function. They accept responsibility and don't sidestep it, but 'we' gets the credit.... This is what creates trust, what enables you to get the task done."[287]

By behaving authentically, managers establish the groundwork for trust. Authenticity is a relatively new concept in the lexicon of leadership, although the idea dates back at least to the classical Greeks. An inscription at the Delphic oracle, attributed to the Seven Sages, says "Know thyself." In Shakespeare's Hamlet, Polonius counsels his son, "This above all: to thine own self be true." Interest in authenticity and its application to business has been fueled by concerns about how unethical behavior can produce large-scale economic failures (Enron, WorldCom, Barings Bank, and Parmalat, to name a few examples). In response, many organizations have developed codes of conduct or values statements that include references to ethical behavior. External pressure to behave ethically might produce some positive effect, but our conception of authenticity draws on a different source. As we mean it, authenticity originates from within the individual. It implies a drive to behave with integrity even when no outside force demands compliance.

Authentic behavior is not a unitary, either-you-have-it-or-you-don't concept. Rather, it comprises a set of attributes that any individual may display to a greater or lesser extent. A research team led by Arizona State University's Fred Walumbwa studied populations as diverse as Chinese, Kenyans, and North Americans. They found supporting evidence for four components of authenticity:

Self-awareness. Mindfulness about how one experiences and makes sense of the world. Self-awareness denotes an accurate understanding of personal strengths and weaknesses, and insight into how one's behavior is perceived by, and affects, other people.

Relational transparency. Being consistent and genuine in interactions with others and presenting one's true and honest self to the world, without pretense, manipulation, or intentional distortion. That value of transparency applies to close associates as well as to oneself; a manager strong in relational transparency helps others identify both positive and negative aspects of their behavior.

Balanced processing. Willingness to evaluate all relevant information, including data that are challenging or uncomfortable, before reaching a decision. Authentic leaders are less likely than others to ignore or distort information they may not want to hear, to deny the relevance of messages about their personal shortcomings, or to punish the bearers of those messages.

Internalized moral perspective. Guiding one's behavior and decisions by personal ethical standards rather than by external pressures from a group, organization, or society. As Walumbwa and his colleagues explain it, a person's moral perspective is guided by deeply held values that enable the individual to avoid acting merely to please others or to attain rewards or avoid punishments."[288]

A group of researchers from the University of Nebraska has studied and elaborated on authentic leadership. They summarize the relationship between authenticity and trust this way: "Authentic leaders act in accordance with deep personal values and convictions, to build credibility and win the respect and trust of followers by encouraging diverse viewpoints and building networks of collaborative relationships with followers."[289]

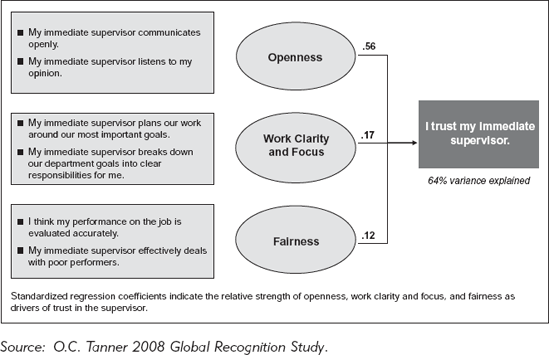

Our research suggests that three primary factors influence trust between managers and employees. Trusted managers, we've found, communicate openly, focus work on what matters to the unit, and handle performance management processes with objectivity and fairness. These elements appear in Exhibit 9.1. Authenticity, as we will explain, adds power to each factor.

Paul Zak, professor of neuroeconomics at Claremont Graduate University, has studied both the economics and the neuropsychology of trust. Zak says sunlight nurtures trust and darkness destroys it.[290] Openness that fosters trust lets sunlight in. This means frequent, honest, personal chats on topics like performance, department and company success requirements, and status updates. Supervisors, in turn, must listen to the opinions and concerns of employees, whenever employees have something to say. Electronic media provide no substitute for personal contact when it comes to building trust. In the 2009 Edelman Trust Barometer,[291] 40 percent of a sample of people across eighteen countries said that personal conversations—with friends, peers, others in the organization—were a credible, trusted source of information about companies. Only about half that number said social media, blogs, and Web sites provided trustworthy information. A meta-analysis by Kurt Dirks of Washington University in St. Louis and Donald Ferrin (then of the State University of New York at Buffalo, now with the Lee Kong Chian School of Business, Singapore Management University) showed that employee participation in decision making is critical to developing trust.[292] Employee involvement in key decisions signals that the manager has confidence in, as well as concern and respect for, the contributions of employees.

Openness draws on the self-awareness and relational transparency elements of authenticity. Self-aware managers understand their personal strengths and weaknesses; they have what we think of as internal honesty. They also have insight into how their expressions of leadership will be received and interpreted by others, given the context in which their words are spoken and their actions taken. Words and deeds associated with a crisis have particular power to reinforce or undercut the appearance of self-awareness. U.S. President George W. Bush discovered this in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

In the last few days of August 2005, the sixth largest hurricane ever recorded, and the third strongest ever to make landfall in the United States, caused more than 1,800 fatalities and an estimated $75 billion in physical damage.[293] The tragedy created a leadership moment for President Bush, an occasion for him to express his empathy with the victims of the storm and to give them confidence that he understood and knew how to alleviate their suffering. By all accounts, he failed to seize this opportunity. Most famously, he expressed support, in a typically informal way, for Federal Emergency Management Agency chief Michael Brown: "Brownie, you're doing a heckuva job." Brownie, it turns out, had not been doing a heckuva job. Just ten days after Bush's tossed-off endorsement, Brown resigned amid public outrage over his scant qualifications and the administration's failure to provide prompt and effective aid to New Orleans and the rest of the region. Bush clearly did not understand how his misplaced loyalty to a subordinate, and his vernacular, almost nonchalant way of conveying that support, would offend hurricane victims. Self-awareness calls for reflection, mindfulness, and caution in expression. President Bush failed on all three counts.

Open communication between manager and employee also depends on a transparent relationship between them. Transparency connotes clarity and absence of obstruction in the mutual expression of each party's true motives and needs. In a transparent relationship, each person presents his or her true self—a genuine individual brand, so to speak. By brand, we don't mean an artifact of self-promotion or a self-serving depiction of admirable features only. Instead, we define a personal brand as the behavioral promises that each of us makes and keeps. By staying consistent in what she says and does, a manager gives others confidence that they can understand and predict how she will react in any situation. A brand thus becomes an efficient bundle of impressions people can store cognitively and refer to when they need to know who we are and how we will respond to circumstances at work.

Personal brands are familiar to all of us. Celebrities routinely create them as a way to make their images stick in the minds of the public. Sometimes their brands stand out for their consistency and genuineness. Actor Paul Newman, for example, was known as a skilled actor, devoted family man, generous philanthropist, and successful businessman. His behavior reinforced these impressions. He won an Academy Award in 1987 for The Color of Money and also received eight other nominations during his career. All proceeds, after taxes, from his Newman's Own food products go to charity. He was married to actress Joanne Woodward for fifty years. When asked about infidelity, he said, "Why go out for hamburger when you have steak at home?" Newman's brand reflected competence in his craft and a truthful and steadfast devotion to his values.

In contrast, consider what has happened to the personal brand associated with golfer Tiger Woods. Thanks in part to his connections with companies like Nike and Accenture, Woods reinforced his reputation as the best golfer of his generation—and perhaps of all time—by presenting a set of admirable personal traits: focus, skill, competitiveness, tenacity, discipline, analytical insight. He wasn't just good at hitting golf balls—his brand reflected the ultimate in talent and success. He came up a little short on integrity, however, as the world discovered when his numerous sexual transgressions became public. He had frequently been seen in public with his beautiful wife and children, adding doting father and attentive husband to his collection of admirable features. His peccadilloes therefore became all the more damaging to the brand image that he and his sponsors had created and cultivated.

We hasten to say again that our definition of brand relies on truth. If the brand and the person beneath it are inconsistent, then relational transparency is absent. Tiger's cautionary tale reminds us that integrity—firm adherence to a code of behavior under all circumstances—is crucial to relational transparency. If self-awareness is internal honesty, then relational transparency is external honesty. The two reinforce each other. When they come together, an individual (manager or not) will:

Have a clear sense of his personal traits (the brand elements)

Enact them consistently under all circumstances (deliver the brand promise at all times)

Admit mistakes and deviations from expectations (everyone makes them; honest admission is necessary and cover-ups always work out badly)

Not take himself too seriously—This is Rule Number 6 from Roz and Ben Zander's The Art of Possibility. Rule Number 6 (there are no other rules) urges people not to get too caught up in personal brand creation. It happens naturally, organically, as we simply behave reliably according to personal standards. Humility and sense of humor are important; too much effort seems strained and insincere. Conveying a genuine personal brand encourages others to do the same. The Zanders say that, "When one person peels away layers of opinion, entitlement, pride, and inflated self-description, others instantly feel the connection. As one person has the grace to practice the secret of Rule Number 6, others often follow."[294]

Employees must believe that managers can guide employees' efforts toward the work that matters most to the success of the unit and of the broader organization. It's difficult, in practical terms, to place every element of every job clearly into the bigger picture. That's where trust comes in. When employees trust managers to understand the organization's direction and link work to those higher-level intentions, employee confidence in the significance of their tasks increases. Initiative and performance both go up as well. Improved performance, in turn, underpins increased trust.

Kurt Dirks studied the trust

Making a tight connection between unit goals and the actions necessary to achieve them requires thorough, unbiased information collection combined with objective assessment—the balanced processing component of authentic leadership. We know from our discussions in earlier chapters, however, that cognitive biases (framing effect, illusion of control, planning fallacy) often confound managers' analytical efforts. These biases can sidetrack even the best attempts to achieve accuracy and arrive at well-supported conclusions. Balanced processing can help by forcing managers to look beyond the unchallenged beliefs and unexamined attitudes that threaten to distort their reasoning.

In deciding how to pursue the war in Afghanistan, President Barack Obama employed an exhaustive process of information collection and evaluation, in the hope of developing a logical, philosophically defensible strategy. His approach demonstrated balanced processing by:

Taking into account extensive information from various, often competing sources. The strategy formulation process required some three months to unfold. During that time, the president reviewed three dozen intelligence reports and received information and advice from military leaders, cabinet heads, members of congress, and diplomats.

Ensuring that the analysis was framed not only in a military context (through a critical look at comparisons with the Vietnam conflict) but also an economic one (as revealed by a private budget memo estimating a $1 trillion cost for expanded military presence, roughly the same amount as Obama's health care plan).

Considering elements under U.S. control (troop deployment numbers, for example) as well as factors less subject to American influence (corruption in the Afghan government and Taliban entrenchment in Afghan society, for instance).

Mapping alternatives to clarify actions and consequences. Central to the president's thinking about strategy was a graph plotting troop numbers over the period of build-up and draw-down. Obama challenged his advisers to move the curve to the left—that is, augment troop numbers quickly, achieve military goals, and then withdraw the forces swiftly.

Encouraging debate and disagreement. He not only invited competing voices to propose options, but also withstood pointed criticism of the final plan and even threats from leading members of Congress to withhold financing for the war.[297]

By placing information and analysis in several contexts, identifying both controllable and noncontrollable elements, and looking at scenarios from many perspectives, the president's planning process enabled his team to confront cognitive biases associated with problem framing, illusory control, and overconfidence in planning.

In the context of trust, balanced processing represents intellectual honesty in the interest of aligning effort and resource investment with group goals. It requires dedication to objective and impartial reasoning, even when taxing or personally uncomfortable. Sometimes, listening to opposing points of view will test a manager's dedication to remaining away from center stage. Astute managers know that participating in the debate and controlling the discussion are different things.

Taken to its extreme, balanced processing appears to suggest indecision and temporizing. Competitive environments rarely afford the luxury of extended time to formulate and carry out strategic plans. Managers must therefore weigh the need for a balanced and comprehensive analytical approach against the inevitable pressure to move quickly and decisively.

In the workplace context, fairness takes four distinct forms:

Procedural fairness (fair process). The perceived consistency and equity of the processes by which performance is assessed, rewards are allocated, or other organizational decisions are made. People believe processes are procedurally fair when they have the ability to voice their views and exercise influence over the outcome. Managers support procedural fairness when they answer such questions as, "How will this work?" and "What's the intention?"

Distributive fairness (fair outcome). The degree to which an outcome conforms to the individual's personal sense of worth or deserving. Distributive fairness is heightened when people see the connection between results and performance ratings, between performance and rewards, between contribution and outcomes. Managers increase employees' confidence in distributive fairness when they deliver a just and equitable (if not necessarily equal) outcome—in effect, the individual manifestation of a fair procedure through fair distribution.

Interpersonal fairness (fair treatment). The consideration, respect, and sensitivity that people receive when decisions are made and enacted. Interpersonal fairness reflects how people experience the emotional context of reward delivery and other organizational events. Managers heighten the sense of interpersonal fairness when they listen to their employees' concerns one-on-one, act on them whenever possible, and pass them on for an organizational response only when necessary.

Informational fairness (fair explanation). The clarity of explanation that accompanies events like performance discussions and reward distribution. The criteria for informational fairness include reasonableness, candidness, thoroughness, and timeliness. No varnishing the truth or holding back information, however unpleasant it may be.[298]

Employees pay special attention to how their managers handle the distributive, interpersonal, and informational elements of perceived fairness. Trust increases when people believe their performance has received a fair assessment and when supervisors ensure that others are held to similar standards. Tolerance of low performance reduces perceptions of fairness and, consequently, of trust in the manager.

People tend to look to organizational policies in forming judgments about procedural fairness. But attitudes toward managers dominate the overall trust calculus. Research shows that perceived managerial trustworthiness influences people's view of the trustworthiness of the organizational entity as a whole, whereas the opposite does not seem to be true. A study by Jaepil Choi of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology surveyed 265 supervisor-employee pairs in four companies in the northeastern United States. The analysis confirmed that employees look to their managers for distributive, interpersonal, and informational justice. But Choi also observed that "the manager's behavior did seem to play a significant role in determining employees' reactions both to the manager and to the organization. A supervisor's behavior has an immediate impact on various aspects of subordinates' organizational life, so it is not surprising that perceptions of the supervisor's fairness would have great implications for employees' reactions."[299]

Uncompromising fairness, reflected in performance assessment and myriad other ways, requires an unerring ethical compass. In the authenticity framework, this quality emerges as internalized moral perspective. It is the most fundamental form of honesty, the element of character that underlies internal, external, and intellectual honesty.

The most dramatic examples of fairness and internally anchored morality are often negative, cases where the absence of internalized moral perspective brought low an individual or an entire corporation. The first decade of the twenty-first century produced many examples of moral compasses that failed to point true north. The downfall of New York governor Eliot Spitzer is one. Spitzer rose to power as a fierce crusader for ethics in business. As attorney general of New York, the position he held for eight years before winning the governorship, he aggressively pursued Wall Street fraud, among other targets. He went after such high profile firms as Merrill Lynch, which he attacked for distorting its stock analysis to punish companies that weren't Merrill customers. The resulting settlement cost Merrill Lynch $100 million and helped make Spitzer Time Magazine's "Crusader of the Year" in 2002.[300] Over time he added investment banks, insurance companies, and environmental polluters to his target list. Spitzer seldom missed an opportunity to chide his perceived adversaries, as he did in a piece he wrote for The Wall Street Journal Online in April 2005. In that article he scolded the Journal and business lobby groups for not condemning corporate wrongdoers more vehemently. He wrote, "Why wouldn't the Journal and business lobby groups denounce such improper conduct? Why wouldn't they advocate the highest standards and urge prosecutors to root out the corruption and restore the integrity of the markets?" He went on to lay much of the blame at the feet of immoral executives: "A key lesson from the recent scandals is that the checks on the system simply have not worked. The honor code among CEOs didn't work."[301]

Spitzer showed the flaws in his own honor code just three years later when he resigned the governor's office after revealing his involvement with high-priced prostitutes. It turns out that, just to complete the irony, Spitzer had prosecuted at least two prostitution rings as head of the state's organized crime task force. In a press conference he held a few days before giving up the governorship, Spitzer said, "I have acted in a way that violates my obligation to my family and violates my or any sense of right or wrong. I apologize first and most importantly to my family. I apologize to the public to whom I promised better."[302] He evidently grasped the concept of an internally anchored code of moral behavior. His simply did not guide him in the right direction.

Enron, the corporate icon of failed moral standards, shows what happens when an organization's culture deviates from a central code of ethical behavior. Enron's major transgressions are well documented. Improper accounting, questionable insider transactions, and cutthroat treatment of customers and partners made the company a paradigm of corporate dishonesty. Even in little ways, the behavior of Enron's leaders demonstrated the damage that can come from ignoring moral values. To be sure, Enron had a stated set of values: respect, integrity, communication, and excellence. But, says Sherron Watkins, former vice president for corporate development and the most famous Enron whistleblower, "Enron executives did not demonstrate that they valued integrity; it was way down the list." For example, executive travelers were directed to use the travel agency owned by Sharon Lay, sister of Enron Chairman and CEO Ken Lay. "Forcing the employees to use his sister's agency told everyone that once you get to the executive suite, it's okay to take assets for you and your family," says Watkins.[303]

The absence of internalized moral perspective among Enron executives contributed to a dearth of trust at all levels of the company. Enron prided itself on being full of brainy people. The company reinforced its smartest-guy-in-the-room culture through a performance evaluation process that came to be called "rank and yank." Employees and managers spent about two weeks each year ranking fellow employees' contributions to the company, giving scores from 1 down to 5. The process included a forced distribution, so that each division was required to put 20 percent of its employees into the bottom category. That bottom fifth was supposed to be shoved out the door.[304] Enron was not a place where performance assessment created a platform for improvement. Either you were bright enough to make it or you weren't. It's hardly surprising, therefore, that people had every incentive to act in untrustworthy ways by giving their peers low ratings, even if not deserved, and thereby making themselves look better by comparison. They had little incentive to look at the honest facts, particularly if the facts told an inconvenient story. Moreover, when you play a zero-sum game, where somebody must lose for others to win, pressure to make the numbers becomes pressure to make up the numbers.[305]

This kind of performance evaluation process falls far short of meeting the criteria for engendering trust. Instead, it makes competition turn vicious, trust and authenticity disappear, organizations fail, and cheating to become institutionalized. As the University of Nebraska research team expressed it, "Cultures that reflect a preoccupation with short term performance results at the expense of ethical considerations will not facilitate the development of authenticity, in part because honesty, integrity, and high moral standards are not distinctive and/or prototypical values."[306] Enron's people may have been the smartest in the room, but their success was ultimately limited to what they could accomplish by taking from each other and from their external partners. No amount of brain power could expand their success beyond the limited boundaries of their sparse trust and impoverished authenticity.

The world of corporate ethics is full of gray areas, situations where the right choices can be unclear as well as difficult. Sherron Watkins suggests a simple test that anyone—executive, manager, or employee—can use to choose the path to take. When faced with a morally ambiguous decision, she advises, tap into your internal moral perspective and then ask yourself three questions:

Would you be comfortable explaining your decision to a respected manager?

Would you be satisfied with how your decision could be treated by the media?

After explaining your rationale, would you be at peace with the reaction you got from your mother?

If the answer to any of the 3M (manager, media, mother) questions is no, then the decision doesn't measure up on your internal moral yardstick. And if that's the case, Watkins has this warning: "If your own personal value system is not validated or if you are uncomfortable when your value system gets violated, leave that organization. Trouble will hit at some point." She should know.[307]

Maintaining openness, structuring work for maximum clarity and importance, and acting with fairness all seem like good practices to embrace under any circumstances. Why do they have any special power to increase trust? Because each factor, in its way, makes less daunting the leap of faith that trust requires. When it comes right down to it, none of us can predict with complete accuracy how anyone will act in a given set of circumstances. Hence, trust requires faith—the belief that things will turn out all right even in the absence of perfectly predictive information. Anything that closes the faith gap builds comfort and certainty. Candid discourse, for example, helps people comprehend the risks required and the rewards available in their work. Focusing effort on what really matters and translating goals into relevant personal actions provides a roadmap to performance—fewer mysteries, less ambiguity, a clear destination, and a reason to drive toward it. Fair and accurate performance evaluation and real consequences for high and low performance let people know where they stand against the agreed-on criteria for reward and recognition. The ultimate payoff closes the circle: performance produces results, outcomes justify trust, and recognition of performance elevates engagement.

Authenticity and trust influence how managers enact all other elements of the manager performance model, beginning with task execution.

In the context of job design, trust produces two important benefits. The first is psychic and has to do with stress management. As we discussed in Chapter Five, the most productive jobs combine high but achievable performance demands with abundant support resources, including the manager's trust. Conversely, as Exhibits 5.1 and 5.2 illustrate, high demand coupled with low support produces jobs that are stressful or impossible to perform. A downward spiral takes hold: lack of trust reduces autonomy, which increases stress and diminishes individual well-being. Stress hormone production goes up and trust drops further.

Managers make this a positive circle when they express trust in employees and back it up by fostering workplace autonomy. This increases individual ability to handle high demands and manage stress. A self-aware manager who balances input before making a decision will evaluate the strengths, experience, and development needs of team members before allocating tasks. A manager who works to build transparent relationships with employees will enjoy a level of rapport that makes those conversations flow easily. Endowed with balanced processing, the manager will solicit input from employees as he considers how to design fulfilling, strategically important jobs. What better way can a manager communicate trust than by saying, "Tell me how your job should be defined and let me know what support you need to accomplish it. Your work should give you plenty of autonomy because I trust that you will do the right thing and perform well." Paul Zak says, "Autonomy works because rather than being the innately selfish homo economicus ... our research shows that human beings are more accurately described as homo reciprocans, or reciprocal creatures.... People trust those who trust them, and distrust those who distrust them. Leaders must choose which side of the trust/distrust dichotomy they want to be on."[311]

The second benefit of workplace trust shows up on the economic side of the ledger. Trust reduces the cost associated with vigilance and monitoring, and thereby conserves energy and improves productivity. This effect is relevant both in the microeconomic environment of jobs within companies and in the broader macroeconomy. In the latter arena, economists have placed societal levels of trust among the most powerful growth promotion factors. People who trust each other require less-onerous contracts to do business and so are more willing to make investments without burdensome guarantees or expensive protections.

We could well expect this same effect to emerge in the competitive marketplace. Companies with higher endowments of trust should experience better cooperation among individuals, teams, and units; less employee time investment in monitoring events and negotiating for rights; less manager time required to defend decisions; and more rapid acceptance of work requirements. Each of these could contribute to a cost advantage or an edge in innovation or customer responsiveness.

Employee development, and the goal setting and performance assessment processes that support it, require dialogue. Managers who amass critiques and data to unload on people at annual review time create an environment in which employees feel scrutinized and untrusted. Alternatively, continuous discussion of goals and performance reinforce employee belief in interpersonal and informational fairness and build confidence in manager trustworthiness. Relational transparency helps form the basis for this kind of high-trust exchange. Particularly in flexible career models like the lattice-and-ladder approach, trust is critical to ensuring that all parties—individual, manager, and organization—benefit from creative work and development arrangements. A manager who conveys self-awareness and relational consistency gains insight into others and can interpret employee words and actions in the right context. He can differentiate manifestations of individual personality from artifacts of the work environment (the dilemma posed by the actor-observer bias). Conversely, a manager with intellectual honesty, bolstered by balanced processing, will have a counterweight to the illusion of transparency. This provides a way to avoid overestimating how well he understands employees' mental states. When these factors come together—when employees believe that supervisors have acted fairly and in good faith to help them craft personalized development and career advancement paths—their confidence in supervisor fairness and their trust in their managers increase.

We know from our discussion of the deal between individual and enterprise that this exchange incorporates both tangible and intangible elements. The intangible, social elements of the exchange tend to have indefinite terms, long time frames, and unspecified value metrics. In other words, they have their basis in relational contracts. Consequently, trust becomes an important part of the ongoing exchange. Indeed, trust grows stronger over time on a foundation of positive interchanges between employee and organization, facilitated by the manager. Self-awareness enables a manager to understand his own reward motivations and to use those as points of reference for considering the deal with employees. Relational transparency helps ensure that the negotiation between employee and manager, acting as agent for the organization, produces a fair outcome for all parties. Employees can have confidence that a manager with a strong internalized moral perspective won't exploit them.

The tangible, financial elements of the deal tend to have programs and formally defined schemes as their foundation. They rely on transactional contracts, which reduce the need for trust between the exchanging parties. In virtually every workplace, employees engage simultaneously in both social and economic exchanges, which tend to operate relatively independently.

But the two kinds of deals differ not only in the amount of trust they require to maintain, but also the behaviors they produce. The social elements of the deal show stronger correlations than do the economic aspects with emotional commitment to the organization (that is, staying with a company because you share its values and feel a bond with the organization and its people). The economic elements of the deal have a closer association with what social scientists call continuance commitment (staying with a company because it's financially risky or costly to leave).[312] Overall performance, attendance, punctuality, and willingness to invest discretionary effort in the job all connect more closely with social, trust-based exchanges than with the transactional, program-based elements of the deal.

Trust acts as a lens through which people interpret the messages they receive from managers. Employee attention to the meaning of those messages becomes sharper when they bring news about change, whether small ("Sorry, your budget request was denied") or large ("It looks like we'll be shutting down this division and starting layoffs soon"). When change becomes imminent or real, people naturally speculate about the implications for them. They develop alternative scenarios, counterfactual assessments of reality that allow them to test the fairness of actual or expected outcomes. One counterfactual category focuses on would: would circumstances have been better if they had turned out differently—if the promotion had come through, if the merger hadn't happened, if the cotton fiber division hadn't been closed down? A second counterfactual involves could: could the manager have taken a different course—worked harder to get me the promotion, argued against the merger, fought to keep the cotton division going? The third type of counterfactual is should: should the manager have acted differently, or were the decisions either rational or out of the manager's control?

This process of counterfactual scenario-building provides a general framework for understanding how people process the circumstances of change. In real life, however, things aren't so neat. The preexisting environment of trust between employee and manager exerts a strong influence on how people interpret change-related explanations. According to researchers Brian Holtz and Crystal Harold of Rutgers University, "The level of trust in one's manager can form a heuristic context to evaluate managerial explanations, and the stronger the conviction, positive or negative, the more likely it is that heuristic processing will dominate the processing of specific messages."[314] In other words, people view the manager's explanations about change through the optics of trust. If a history of transparent, trust-enhancing exchanges exists between employee and manager, people will view explanations about change as sincere and legitimate. If employees believe their managers have remained open to receiving information and considering alternatives, they can have confidence that the outcomes of change are likely to be reasonable and fair, if not always favorable. A trusting social context between employee and manager establishes what Holtz and Harold call "a broad zone of acceptance for managerial decisions."[315] But if a manager has compromised trust through lack of openness, vague connection between individual work events and unit success, or violation of the requirements for fairness, then even logical and otherwise credible explanations will be interpreted by employees as inadequate, insincere, and not legitimate.

Employees in today's workforce demand competence and judgment from their managers. But they also want more. They come to work each day with a deeply ingrained ambivalence about the necessity for—not to mention the quality of—the leadership they are about to experience. They want fulfilling work, a chance to learn, a fair deal, and a guide through the uncertainty of a changing landscape. But they also want managers who will care about their well-being and refrain from pretense and game playing. In other words, they want authenticity and trust. The endowment of trust shared by employee and manager is a fragile asset, more easily destroyed than created. Building and preserving it requires effort from both sides.

In Chapter Three, we discussed transformational and transactional leadership. Although authentic leadership overlaps with both to some degree, the differences, especially with transformational leadership, are instructive. Authentic leaders, as we've emphasized, are guided by an inner compass, by their own deep sense of self. Transformational leaders may be just as honest and ethical, but their behavior has an external orientation. Transformational leaders nurture and develop the next generation of people with aspirations to senior leadership. Authentic leaders, in contrast, develop a population of people who share the value of authenticity. Leaders with a transformational style often project charisma, even star appeal. A manager executing his leadership duties authentically, in contrast, will be honest and forthright, though not necessarily charismatic. An authentic manager will project charisma only if that aspect of personal presence forms part of his true character. People acting with authenticity tend to rely more on personal example than on emotional appeal when it comes to inspiring action among followers.[316]

Hence, authentic leadership works best on a personal, one-to-one level, consistent with our definition of the leadership required of first-line supervisors and managers. A manager who demonstrates the highest levels of authenticity will consistently:

Not just act with honesty and integrity—these are table stakes—but also remain mindful of all facets of her personal brand, understanding how employees experience her leadership style across a range of situations

Achieve the difficult balance between perceiving and responding to individual employee differences while also considering that employees may react to workplace conditions much as she does

Not merely perform thorough analysis of data and information, but also go further by seeking out contrasting opinions and challenging points of view

Reinforce the connections among individual, work unit, and organizational strategy, because underscoring the importance of work builds trust, reduces stress, enhances resilience, and supports well-being

Follow the fairness requirements scrupulously, even when organizational programs and executive decisions may make the criteria difficult to uphold

Demonstrating authentic and trust-engendering behaviors takes time and energy. The manager who sits isolated in her office may produce much direct output, but only at the cost of a lost opportunity to spend time with employees. People trust people they know, and they know people with whom they interact and share experiences—which happens on the other side of the office door and outside the cubicle walls.