CHAPTER OUTLINE

Manager Contribution — The Player - Coach Job

Manager Competency — The Technical Skill Dilemma

The Size of the Job—Span of Control

Because They Thought They Had To

Because They Thought They Should

The Truth about Spans

Building the Role System

In the wild, the lives of vervet monkeys are like one big soap opera. Some sit at the top of the social hierarchy, with better access to food, mates, and grooming opportunities than lower-ranked troop members. But subordinate monkeys, like soap opera characters, can be a deceptive lot, using trickery to improve their position in life. For example, vervets have been observed using a warning call (intended, say, to alert the troop about a specific approaching predator) to send the other monkeys scrambling up a nearby acacia tree. This strategy leaves the lone monkey with sole access to the juicy berries, a food source he would have to share with higher-ranking animals, if they weren't busy hiding from a nonexistent leopard.

Studies of vervet monkeys have enlightened psychologists about how dominance works. One interpretation of dominance—high social status achieved and preserved through skillful connection—has important implications for the manager position. How is it, exactly, that individuals ascend to manager and executive jobs, where they have authority over others? Is the process as rational as we would like to think, or are other forces at work?

We have considered some of the organizational phenomena that make the manager's job difficult and cause no small amount of resentment against the people who hold manager positions. In Chapter Three, we laid out a manager performance model that aims to address these concerns, to transform managers into a competitive advantage rather than merely an inert layer in the organizational hierarchy. We ended the chapter with a question: why don't managers more consistently execute these performance requirements? We will address this question by considering key elements of the manager's role and exploring how the construction of the job affects the execution of the performance model. We will focus on three major elements of the manager's position:

What the job is supposed to accomplish (the determination of how managers do and should spend their time and how they ought to contribute to the organization's quest for better product and service offerings, lower process cost, or stronger customer relationships)

How managers are expected to do what they do (the balance of relational competencies and technical skills and how that balance determines the way managers go about their work)

How the reporting scope of the manager's job affects performance (the number of employees the manager oversees and how that number renders the job feasible, impossible, or somewhere in between)

Sometimes, in a team sport like basketball, a single person will play the dual roles of player and coach, analogous to an actor-director in movies or a musician-band leader in a 1940s swing orchestra. In 1967–68, Bill Russell, in the player-coach role, led the Boston Celtics to the championship of professional basketball in the United States. He may have been the last truly successful example of that approach, at least in professional sports. Those who hold him up as an example of how a player-coach can succeed forget that, in the prior season, the Celtics led by player-coach Russell had failed to make the playoffs for the first time since 1956. His success the next season came only after he cut back his playing time and concentrated on coaching.[116] Even Bill Russell, who had exceptional ability in both disciplines, couldn't do both jobs equally well at the same time.

Although the player-coach structure has produced only mixed results, American business has virtually institutionalized it. Across a range of industries and functions, organizations consistently expect line managers, especially those at the first supervisory level, both to perform and to oversee work. In a Webcast we did in partnership with the Human Capital Institute (HCI), we asked the participants (102 human resource managers and executives) what percentage of their managers spend at least half of their time doing the work performed by their units. More than half of the survey respondents said that a majority of managers spend at least half their time in direct personal production. Almost one-third of the respondents said that 80 percent of their managers concentrate more than half of their time on personal output.[117]

When we did focus groups with sixty-three managers in a midsized commercial bank in the United States, the participants told us clearly how the push me–pull you aspects of their jobs diffuse their attention. Their greatest frustration, they said, comes from having to adopt a player-coach role, juggling demands for personal production with the responsibility for leading people and managing work processes. They said they spent almost 40 percent of their time doing hands-on work, and less than one-third focusing on people. Almost 60 percent said that solving this problem would be one of the best ways to enhance their effectiveness as managers. As one put it, "Managing people is a small piece of what I do. Our managers are working managers, and they own the projects they're responsible for." Another pointed out one underlying cause of the problem: "Ideally I'd concentrate on managing, but as it is I don't have enough resources, so I have to get in there and help." They lobbied for a job structure that would decrease hands-on time to 30 percent and increase people-related time to more than 40 percent.

We got comparable results from a similar-sized study we did of a U.S. utility company. Almost 60 percent of the utility managers said that one of the best ways to improve their managerial effectiveness would be to reduce the time spent juggling personal production tasks and oversight responsibilities.

Table 4.1 shows some of the reasons organizations cite for instituting player-coach structures, points out the flaws in those reasons, and suggests another way of thinking.

The player-coach construction has links to the all-too-common tendency to promote people to supervisory roles chiefly for their technical abilities. After all, doesn't it stand to reason that a technically proficient supervisor should spend most of her time selling farm supplies, designing communication networks, or writing copy? Isn't that how the organization can achieve the highest possible return on the compensation it pays that person? In fact, it's rare to find a supervisor or manager who does no hands-on work. Virtually all must balance some amount of playing and coaching. At Southwest Airlines, for example, supervisors work next to their employees. But they do so not because they perform better than the people on their teams. Instead, they do so because it provides the experience they need to give effective coaching and performance feedback. At SAS, managers do some of the work to free up highly skilled programmers to focus on what matters to them. The issue is not one of absolutes, but rather of optimal balance for the highest productivity of the unit as a whole, not just the highest manager output. As one consultant notes, "Most managers in the technical fields were superb individual contributors, which makes sense—it's how they got identified as 'management material' in the first place. Still, being good at doing something doesn't mean you'll be good at teaching others to do it or motivate them to get to it done even if they know how."[118]

The predisposition to attach leadership responsibility to domain-specific abilities is a ubiquitous organizational phenomenon with deep psychological underpinnings. At least one CEO, Indra Nooyi of PepsiCo, has said that this is part of a successful corporate culture: "PepsiCo is a meritocracy. Hard work gets recognized.... There are some skills that I believe are the hallmarks of a good leader. [One is] competence. You must be an expert in your function or area of expertise. You will become known for that."[119]

Table 4.1. Player-Coaches—A Losing Game

Reason for Creating Player-Coach Roles | Problems with the Reasoning | A Better Approach |

|---|---|---|

Source: Adapted from The Fallacy of the Player—Coach Model, The Boston Consulting Group, Inc., 2006. | ||

We don't want a full-time manager overseeing a small group of employees. | Narrow spans of control[a] may be inefficient, but creating player-coach structures is not the best solution. | Restructure units and consolidate activities differently to create reasonable spans of control. |

We have no choice—we can't afford to have managers who only manage. | The math is wrong. It overlooks the additional employee productivity managers can generate if they concentrate more time and energy on leading and managing and less on personal production. | Make careful decisions about who should manage and who should function as an individual contributor. Put people where they can be most successful and don't mix roles. |

We reward our best employees by letting them oversee one or two other employees. | This makes promotion more about reward than about competence in a manager role. | Introduce dual career paths and richer reward and recognition opportunities. Make promotion about ability to perform well in the next job, not technical skill in the last one. |

We don't allow first-time managers to supervise more than three subordinates. | Transitions may make sense, but they should be carefully planned and short-lived. Properly selected and trained, first-time managers don't need to be constrained for long periods to artificially narrow spans of control. | Define spans reasonably and help people make speedy transitions to spans that make sense. |

[a] By "span of control" we mean the number of people who report directly to the manager. This may include part-time, temporary, and contract workers as well as full-time equivalent employees. | ||

People must strike the difficult balance between the need for effective leadership and the innate drive for personal autonomy. Moreover, we must choose when to tolerate leadership and enjoy its benefits and when to avoid elevating someone to a position that might lead to exploitation. We can sometimes mitigate the danger of being dominated by making leadership situational. This means choosing leaders for the abilities required to deal with immediate threats or to capitalize on near-term opportunities. Under this strategy, a clan will delegate temporary responsibility for finding the nearest water hole to the most geographically knowledgeable person. They will choose the wisest and most impartial to restore peace or to render a fair judgment in a dispute. The most aggressive and strongest member will lead them into battle and then humbly return, like Cincinnatus, to membership in the group.[120]

In our HCI Web survey, we asked the participants to tell us how much weight their organizations place on technical and operational skills (as opposed to social and relational abilities) when they promote employees to the first level of supervision. About three-quarters said their organizations place significant weight on technical and operational skills.[121] A researcher who studied supervisors overseeing engineers in petrochemical and engineering organizations summed up her observations this way: "Technical skill is a common criterion used to promote technical professionals into management. Often the 'best and brightest' are rewarded for their technical performance with a supervisory or management track promotion. The underlying assumption of this practice is that individuals who excel in a given position (e.g., engineers) will also excel at supervising individuals in that position." She concluded, with admirable understatement, "This assumption, however, is largely untested."[122]

The tendency to elevate skilled practitioners into managerial positions also occurs in professions less technical than engineering. For example, a study of promotion decisions in large accounting firms showed that technical skills were by far the major criterion for moving from senior accountant to manager.[123] Similar weighting for function-specific abilities also occurs in nursing. In one study of advancement criteria, the data showed that promotion from clinical nurse to assistant nurse manager depended most heavily on clinical competency and knowledge. Demonstrated teaching and supervisory experience and overall communication skills fell further down the list. Clinical competency and knowledge remained a dominant promotion criterion in moving up one more level to nurse manager, tied in importance with communication skills. As the researchers noted, "The fact that managers need very different skills than workers on the front line is not always recognized.... Exceptional nurses may not always make exceptional managers."[124]

At play here is the eponymous phenomenon defined in the late 1960s by Laurence J. Peter, a professor of education at the University of Southern California. The "Peter Principle" states that people advance until they reach their levels of incompetence. As it's often expressed, the cream rises until it sours. In many organizations, the Peter Principle manifests itself as the promotion of technically skilled employees into manager positions for which they are unskilled. In some cases, technicians and scientists actively seek these promotions, even knowing that they lack the needed competencies. They do so because organizations afford no other path to greater prestige and higher earnings. In other cases, organizations either overemphasize the importance of technical ability in the equation of managerial performance, or believe that there are simply not enough people with sound leadership and managerial abilities to fill the available managerial slots.

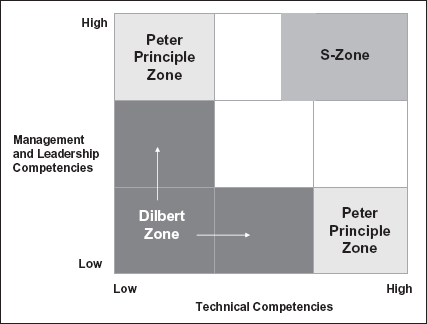

But just what is the relationship between technical skill and the interpersonal, social, and emotional competencies required for successful manager performance? Is it an either/or situation—you can have one, but not the other? Or are they merely contrived opposites, juxtaposed to depict a simplicity that doesn't reflect reality? As with all things concerning human talents and abilities, the answers are complicated. Economists who study how the Peter Principle plays out assume a negative correlation between the two sets of abilities. They postulate an implicit tradeoff—the best technician is a social misfit, the most socially adept are technical goofballs, and you must choose between the two. Of course, the manager ranks may contain members who are incompetent on both dimensions. One academic uses the term "the Dilbert Principle," referring to the pointy-haired boss created by cartoonist Scott Adams, for the tendency of an organization to promote the doubly incompetent.[125]

And what does the research say about the relationship between technical skill and the leadership and management competencies required for successful manager performance? Are they utterly unrelated, negatively correlated, or in some way connected? One study concluded that a small but positive and significant correlation existed between the subject group's average technical and managerial evaluations (0.361, where 1.0 would mean a perfect correlation).[126] These findings suggest that, while not highly connected, the two bundles of competencies need not be considered completely disconnected. Exhibit 4.1 illustrates the array of possible combinations available to an organization.

In looking for candidates to promote into managerial positions, organizations should search for people who have high levels of interpersonal and emotional skills and at least moderate levels of technical competence. People who have this profile of dual competence can avoid both the Dilbert and Peter Principle zones. We find them in the S-Zone ("S" for strong on both dimensions). Who occupies the S-Zone? Managers who have a sound technical foundation to go with well-developed leadership and management qualities. They have recorded strong performance as engineers, scientists, and salespeople. They may not be the top technicians, but they have enough ability in their disciplines to act as credible sources of advice and guidance for their technical subordinates. They have also demonstrated the ability to connect with people, analyze and improve ways of working, and plan for (and achieve) better performance in the future. As a result, they can effectively help people craft engaging jobs, set and achieve goals, become more proficient, and develop the resilience required to weather change. In other words, they can lead (and manage) a unit.

Span of control (the number of people reporting to a manager) represents a fundamental architectural element of organization structure. From the top of the organization to the bottom, span of control speaks to the organization's philosophy about power, accountability, prestige, and rewards. In the last decade and a half, organizations have tended to broaden spans of control for two reasons: because they thought they had to and because they thought they should. Let's examine these two motives.

As we saw in Chapter One, the recession of 2001 and the years following brought widened manager spans as organizations responded to the economic downturn by cutting costs. The logic of cost saving through broadened spans is seductive; flattening organizations by reducing the number of managers lowers operating expense by the dollar value of all of their salaries, benefits, and the variable elements of overhead. But the relationship between wide spans and financial performance is ambiguous at best, as the data in Table 4.2 suggest.

The table shows that firms losing money tend to have relatively narrow spans. As revenue performance improves, spans begin to widen. However, as performance improves further, the widening stops. In fact, spans narrow, from an average of about eight direct reports per manager to about seven and a half. Moreover, the data on organizational layering suggest that flatter structures don't track consistently with better performance. European data paint a similarly ambiguous picture. Overall, money-losing firms have about 8.5 subordinates per manager. The number increases to 10.8 for firms with revenue growth of less than five percent, but drops to 9.0 for companies in the 5–20 percent revenue growth category.[131]

We must be careful about interpreting these data. First of all, the analyses don't trace one group of firms as performance increases or declines, so we can't necessarily infer a trend. Also, we must exercise caution in assigning cause and effect. Do narrowing spans and heightening the organization drive performance, or do better-performing firms simply tend to become (or remain) narrower? These are interesting questions, but the more important question for us is: what really happens to employee attitude and organizational performance as spans change? More on that later.

Table 4.2. Span of Control and Company Performance—Any Connection?

Revenue Growth | Median Manager Span of Control | Median Organization Layers |

|---|---|---|

Source: Organization and Operations Results—U.S. Human Capital Effectiveness Report 2009/2010, Saratoga, a service offering of PricewaterhouseCoopers, LLP, 43, 59, 72. | ||

Loss | 6.4 | 9 |

Less than 5% | 8.1 | 8 |

5%–20% | 7.5 | 8 |

Some observers would say that the widening of spans of control and the pancaking of the organizational pyramid are the inevitable results of commercial evolution. Modern organizations, they would say, have evolved beyond the bureaucratic form. Hierarchy (and, consequently, supervision) has become obsolete.[132] Moreover, a workplace with less supervision would be more in sync with the evolving context of work—greater demand for quality, shorter product life cycles, consistent pressure to adapt to a shifting external environment, increased foreign and domestic competition, and related pressures on trade, communication, and transportation costs. Organizational architects have assumed that layers in the hierarchy slow decision making and raise cost—bad things in an increasingly competitive marketplace.

Organizational flatteners also hailed advances in electronic communication as enablers of hierarchy reduction. According to one commentator, "We used to need hierarchies because we had only primitive communication and information processing capability. Computers, electronic communication, and particularly the Internet have made it possible to flatten almost everything. Flat organizations ... are necessary to deal with accelerating change."[133] The flatter the organization, the easier it becomes for work groups to communicate horizontally with each other. Information moves faster because it doesn't have to go up the chain of command to a supervisor, across to another supervisor, and then down. Eliminating kinks in the communication lines means direct, horizontal, individual-to-individual, group-to-group connection: "Direct communication between individuals is both quicker and more accurate than nodal information flow."[134] And everyone lives happily ever after. At least that's the theory.

The only way to determine the right span of control for any managerial position is to take a hard-nosed look at what you really want managers to accomplish, in the context of competitive strategy. If you believe that managers have existed merely (or even mainly) to disseminate orders and collect information to pass up the hierarchy, then you will surely find better ways to perform these tasks. You will remove managers from the organization, broaden spans, flatten structures, and give everybody direct access to information. If, however, you believe that effective managers do a host of other things that make employees more productive and organizations more successful, then you will take a different course. You will decide how you want managers to contribute and structure their jobs accordingly.

In Chapter Three, we defined manager performance in four action categories: executing tasks, developing people, delivering the deal, and energizing change. Performing well in these areas requires time and ability. It becomes impossible if spans are too wide. Consider examples from four industries: transportation, health care, chemical manufacturing, and call center service.

We saw how managers at Southwest Airlines view their employees as customers. Within this guiding perspective, supervisors do all they can to make their people successful at satisfying customers and keeping airplanes in the air. Southwest's competitive and financial success stems in part from this managerial role definition. This role, in turn, relies largely on creating close relationships between employees and supervisors, which requires comparatively limited spans. In the highly connected team environment of Southwest, supervisors have responsibility for staying close to employees, working side-by-side with them when necessary, coaching them, and giving constant feedback. The organization expects each supervisor to do all this for a group of about nine people. Spans of control at the other airlines included in this study ranged as high as forty. The researchers found a strong relationship between narrow spans and high performance in minimizing customer complaints, handling baggage efficiently, and avoiding late arrivals.[135] The lead researcher on the Southwest project concluded, "My quantitative findings suggest that, overall, large spans are not conducive to high performance in this setting. My qualitative findings further suggest that it is the combination of small spans and facilitative supervision that offers the greatest long-term promise.... It is also difficult to see how high performance can be sustained if, notwithstanding a more facilitative style of supervision, large spans deprive teams of the support they need to sustain strong group process."[136]

In a broad study of seven Canadian hospitals, a group of researchers from the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation studied nurses' spans of control. The team, headed by principal researchers Dr. Diane Doran and Dr. Amy Sanchez McCutchen, looked at how spans interact with leadership style to affect both work experience (as reflected in job satisfaction and turnover) and operational outcomes (measured by patient satisfaction). The researchers confirmed that the two classic leadership styles (transformational and transactional) produce high job satisfaction among employees. They also found that wider spans of control decrease the positive effect of these styles on nurse job satisfaction. Moreover, they discovered that wider spans were associated with lower patient satisfaction and higher nurse turnover.[137]

These findings raise an interesting question: what happens if spans of control are wide but managers nevertheless adopt a transformational leadership style? Doesn't manager behavior trump number of employees? The Canadian researchers found that it doesn't—or, more precisely, it can't. As they wrote in their study summary, "There is no leadership style that can overcome a wide span of control. More specifically, the wider the span of control, the less positive the effect of transformational and transactional leadership styles on nurses' job satisfaction.... As well, wide spans of control decrease the positive effect of transformational and transactional leadership styles on patient satisfaction."[138] Evidently, the effects of even the most enlightened leadership become diluted if managers have too many direct reports. They proposed a simple explanation: "It is not humanly possible to consistently provide leadership to a very large number of staff, while at the same time ensuring the effective and efficient operation of a large unit on a daily basis." They went on to say, "Even if managers possess the desired leadership style, their span of control may interfere with their ability to influence desirable outcomes for their subordinates, patients, and their unit. To succeed, nurse managers must have an optimum span of control that will allow them time to develop relationships with staff."[139]

The same conclusion—that overly broad spans make it difficult for even relationship-focused supervisors to manage effectively—emerged from a research study that looked at production work teams in a U.S. chemical company. Several years prior to the analysis, the organization had undergone a delayering and reengineering program that eliminated management levels. The company had also undertaken efforts to increase employee empowerment, all part of a move toward a lean production mode of operation. As the management structure became sparser, employees took on more responsibility for the actions of the safety committee. This benefit was undercut, however, by the effects of increased spans of control. Wider spans were correlated with more unsafe behavior and more accidents. The researchers concluded, "The potential beneficial impact of empowerment may be tempered by the negative impact of work group size.... Empowering employees may not be enough if leaders have too many members to handle."[140] Towers Watson's research supports this conclusion. We studied human capital metrics from about 150 companies around the world. We found that, as spans of control grow broader, employee engagement, people's willingness to invest discretionary effort in their work, perceptions of learning and career development opportunities, and commitment to the organization all decline.

But what about organizations that have narrower spans of control than others they compete against? Do they derive any benefits from bucking the industry trend? Southwest gave us one example—are there others? A Philippines-based call center organization, eTelecare, provides another instructive case. Spans of control as high as twenty employees per supervisor are not uncommon in call centers. It's a competitive, cost-pressured business; minimizing operating overhead is high on the strategic agendas of call center companies. But eTelecare has a ratio of customer service representatives to team leaders of just 8 to 1, less than half the industry norm. Employees report that team leaders, freed up from the burdens of wide spans, have more time to help employees develop their service skills and technical knowledge. This investment in staff development enables eTelecare to build the skills of its representatives quickly. Some staff make the leap from entry level to licensed securities sales representative in just eighteen months.[141] By narrowing spans of control and focusing on human capital, eTelecare has been able to reshuffle the competitive deck in its business, delivering a differentiated offering in an industry that usually cares mostly about cost.

It is probably obvious by now—though surprisingly few companies we know think of it this way—that the manager's job is a system. It comprises a set of interconnected activities that complement each other and ultimately drive individual and unit performance. Some of you may be thinking, "You seem to be dumping all manager positions into one bucket. Anyone who works in the real world knows that managerial jobs differ across professional disciplines, industries, companies, and functions." True enough—occupation and function matter. Legal department managers, sales managers, and aquaculture managers may have many common job requirements, but their jobs also differ in many ways as well. Researchers from DePaul and Michigan State looked across a range of occupations to see what factors affected the job requirement variations in three categories: conceptual (analytical and general cognitive strength), technical (function-specific operational expertise), and interpersonal (interacting with and influencing others).[143] They found, intuitively enough, that specific technical tasks required by an occupational group—from filing briefs to feeding fish—varied the most among job types. Conceptual and interpersonal requirements, however, varied far less across occupations. The researchers called these two categories "universally important."[144] Thus, although manager skills, work processes, and outputs clearly differ across industries and professions, the basic requirements (and challenges) of the job remain fundamentally consistent. Therefore, we will proceed to propose a managerial system that encompasses a set of central elements with more similarities than differences across the spectrum of manager jobs. We will incorporate the flexibility required to define the role and its components in ways that respect the unique requirements of specific disciplines and organizations.

To construct our model of the manager's role, we need first to define the elements and then set forth some assumptions for how the elements work. Table 4.3 summarizes the manager job elements.

Table 4.3. Elements of the Manager Role

Job System Elements | Definitions |

|---|---|

Net outcomes | Revenue generated by products and services a unit provides, net of the people-related cost (chiefly pay and benefits) required to make and deliver those offerings |

Role elements | Time allocated by the manager to: Direct production: Hands-on effort to produce and deliver goods and services People focus: Creation of a productive work environment for employees in the unit; this encompasses activities like guiding, coaching, developing, rewarding Work process oversight: Monitoring procedures and looking for ways to improve how work gets done in the unit External contact: Making connections outside the group, either with other units inside the company or with external organizations, to improve unit performance (for example, by acquiring information, assets, and assistance) Administration: Handling a potpourri of support tasks, including planning, budgeting, monitoring, and reporting |

Manager competencies | Management: The human capital needed to acquire, develop, and oversee the assets, processes, and systems of the unit Leadership: The full panoply of knowledge, skills, talent, and behavior necessary to develop a vision, plot a path to achieving it, energize others to follow the path, and clear obstacles along the wayTechnical: The skills and knowledge needed to perform well the function-specific, output-producing work of the unit |

Employee competencies, roles, and resources | The human capital employees have to execute their roles, the structure of their jobs, and the freedom afforded them to decide how their work will be done Also the information, tools, funds, and other assets available to them |

Span of control | The number of employees reporting to the manager This encompasses full- and part-time employees, temporary workers, contractors, and consultants |

The variables in the analysis can be manipulated according to these assumptions:

Time is a zero-sum element. A single hour can be invested only once. Tomorrow's time allocations can differ significantly from today's, but once spent, hours are gone.

When managers concentrate on direct production, intuitively enough, they produce more than managers who spend their time elsewhere. Plus, their technical expertise grows with practice, so they'll improve their production over time, to a maximum point. Managers with the greatest technical abilities have the highest personal production.

However, when managers focus more attention on people and less on production, several things happen. The manager's individual production drops as his investment of effort in that area diminishes. But then the magic starts to happen. Employees become more capable as the manager spends more time coaching and developing them. Their engagement goes up as well, for the reasons discussed in Chapter One. As the manager's experience with these relational elements increases, so do his leadership and management competencies. All of this produces an important increment in employee productivity and, therefore, in unit output.

The time that managers spend in work process oversight and forming external contacts can contribute to employee productivity in several ways: improved means of doing things, better access to useful information, and periodic injection of fresh ideas, for example. Hours invested in this element can add an important increment to unit productivity.

Administration is a necessary activity, but one best circumscribed. Planning, monitoring, reporting, and budgeting are important, to a point. Most managers would say they want to reduce the time spent in this category. Organizations should accommodate them to the extent possible.

For the sake of simplicity, all manager competencies fit into three categories: management (the wherewithal to handle assets, processes, and systems); leadership (the relational attributes required to connect with people and help them move toward a specific goal); and technical (function-specific, output-producing skills and knowledge). Of course, these three categories could be infinitely subdivided. Plus, one could argue that they overlap in more than a few areas. Coaching employees in specific technical areas, for instance, might require abilities in all three domains. Increasing the manager's technical prowess affects only his own personal output. Increasing his leadership and management competencies, however, affects the engagement and human capital, and therefore the productivity, of every employee.

A similarly simple three-part cluster describes the employee's place in the system. Competencies encompass the knowledge, skills, talents, and behaviors people use on the job and build over a career. Roles refer to the tasks and responsibilities contained within a job, along with the degree of workplace self-determination available to employees. Resources incorporate the physical, financial, and informational assets required to get the job done. These three elements come together most effectively when managers pay attention to individuals' needs—crafting engaging jobs, recognizing competency with incremental freedom and responsibility, and providing access to experience and wisdom. As the employee role becomes richer, employee productivity rises. Also, people with improving competencies become more capable not only of performing their own work, but also of extending their contribution to intraunit and interunit work planning. In essence, they become able to do some of the work conventionally allocated to the manager.

Span of control affects a manager's ability to spend time with and invest attention in each individual in the unit. Beyond a certain point, spans become so large that the manager can barely say "good morning" to someone as he sprints down the hall to put out the latest fire. Conversely, spans can be too narrow. In one insurance company client of ours, one-over-one structures proliferated because many middle managers had assistant managers. They needed someone to stay behind and mind the store while the managers attended meeting after meeting. The organization chart was a forest of narrow spans, pointed at the top and slender all the way down. Obviously, the output of any unit is the sum of each individual's production. More people in the unit means more product and service output. Moreover, as noted earlier in the chapter, faster and better information flow permits flatter organization structures and broader spans. But let's make sure we have the horse and the cart in the right order. Freer information flow makes wider spans possible; wider spans don't, by themselves, cause information to flow more freely. Likewise, a manager with a narrow span isn't necessarily required to handle every data bite before it gets to employees. The challenge, in other words, is to optimize span of control—as wide as possible, so that the unit has more people producing; as narrow as necessary, so that the manager can help each person become optimally productive.

As with any system, factors affect other factors, and there are many tradeoffs to be considered. Choosing between tradeoff options is, of course, an it-depends game. How much will diverting manager attention from personal work to coaching employees and improving work methods actually increase unit performance? It depends on the specific function. Manager investment in these areas may have greater leverage in departments that have higher complexity and skill requirements than in areas with simpler work processes. How much leverage can a manager get from time spent fostering connections outside the unit or external to the company? It depends on the value that outside information and support can add to any unit's performance. Great insights from the market research function may provide an important boost to the performance of a sales group, for example. R&D needs an external network with which to share research findings. We find, however, that HR functions are sometimes distracted and deflected by an endless search for external benchmarks and best-practice information. How much added value comes from the increases in employee performance that arise from growth in knowledge and abilities? It depends on the job and the learning curve associated with it. In some functions (receptionists, for example), performance peaks after a few months or weeks of experience. Coaching from a manager in the critical early period therefore has a greater influence on learning speed and proficiency than coaching later on. Learning curves for materials scientists are much longer. A manager who can help a young scientist focus his attention on the most fruitful research paths and get ideas more quickly to a revenue-generating stage can add significantly to the financial contribution of a research group. And what about the engagement effect of manager attention to elements like individual development, on-the-job autonomy, and participation in decision making? Again, it depends—on how high engagement is to begin with and on the status of other engagement-driving factors (for instance, the concern senior executives display for employee well-being).

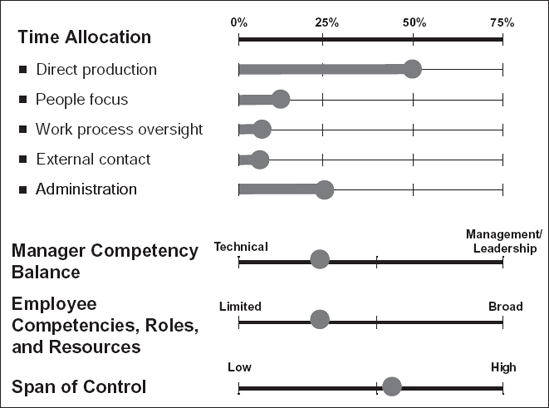

With these dimensions and provisos in mind, consider the two jobs depicted in Exhibits 4.2 and 4.3. The points and lines show the architecture of the manager's role: time allocation; competency and resource balance for manager and employees; and span of control. Exhibit 4.2 shows the job of a manager who has a strong technical focus. Call her the Widget Wizard. She's the most skilled producer on the team, and she spends her time accordingly. Half of her working hours go to directly producing output. The biggest part of the rest (25 percent) goes to administrative activities. She allocates what's left to focusing on people, overseeing work processes, and maintaining some external contact. Her span of control is moderate and her competencies lean clearly to the technical side. Little time investment goes to people (with, say, eight direct reports, an average of only thirty minutes each during a forty-hour week) and to work process oversight. Consequently, employees in the unit perceive limits to their roles and to their ability to improve their competencies and performance. This manager will seem successful, especially if her goals and rewards focus chiefly on what she herself produces. But the people in the unit will suffer. In effect, she has traded her productivity for that of her work group. It is unlikely that this job profile will maximize net revenue. It certainly won't do much to build human capital or enhance employee engagement. Increasing the span of control would only make things worse. At some point, the dilution of manager attention to employee needs ultimately diminishes individual productivity and overall group output falls.

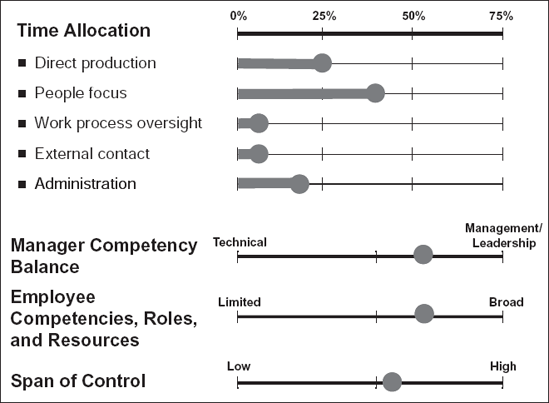

In contrast to the Widget Wizard, the People Powermeister (see Exhibit 4.3) spends one-fourth of his time on direct personal production, enough to keep technically current and professionally credible. A full 40 percent goes to people focus. This allocation yields a generous two-hour allotment of development time per week for each of eight direct reports. Not all of this time goes to one-on-one coaching; some could be invested in group discussions of goals, team learning sessions, and quiet time to plan development strategies for each individual. Equal 10 percent allotments go to improving the work systems used by the group and to building network contacts outside the unit. What chiefly distinguishes this manager role is the more than 50 percent time allocation to activities (people focus, work process oversight, and external contact) that add to individual and group productivity.

We've developed an approach for analyzing the impact of changing the relative weights of these manager role elements. Our calculations suggest that this manager profile could yield a 15 percent increase in revenue production over the Widget Wizard role structure. Expand the manager's leadership and management competencies and figure that commensurate growth in employee competency and autonomy will produce an even more dramatic jump in unit performance.

The real question is: what role structure makes the most direct contribution to competitive advantage? What formula for designing a manager's job makes task execution more productive, people more competent and more suitably rewarded, and change more readily adopted and beneficial? The People Powermeister structure is set up to accomplish those goals by concentrating the manager's time and ability on improving employee performance and growth. The potential for competitive advantage is obvious: for every dollar invested in employee salaries and benefits, this approach can produce higher output than one that relies more heavily on a manager's personal production.

But how do we really know that one role structure produces more than the other? Of course, the results of this analysis depend on the assumptions that go into it. In particular, the People Powermeister role definition requires a manager who has strong leadership and management competence. This means someone in the S-Zone, a manager who knows how to apply his analytical ability and relational savvy with a light touch. Nevertheless, fairly conservative parameters for the impact of additional manager attention to employee performance and work process effectiveness produce dramatic output improvements. Manager attention to employee needs produces a multiplier effect as employee knowledge and abilities increase and the work environment becomes more productive. The incremental production of individual employees soon swamps any output lost as managers shift their time away from hands-on work.

But don't take our word for it—do this business case analysis across various functions in your organization and see what job structure produces the best economic outcome. Autodesk, leading producer of 2D and 3D design software for manufacturing, building, construction, engineering, media, and entertainment, did just that. In 2005, the company set about to improve the productivity of its sales force. As part of the analysis, Autodesk conducted a survey to determine how high-performing sales managers spend their time. The analysis team discovered that the best performers differentiate themselves chiefly by spending more time than other managers on coaching sales representatives. For example, in the EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) sales region, high-performing managers spent about two hours per week more than other managers on coaching activities. Star managers also focused more attention on helping reps with pre-sales planning and deal closure and more time on internal coordination with other functions. The time allocation analysis revealed that some sales managers in another key channel, the value-added reseller group, also had challenges. They carried a heavy burden of administrative, compensation, and post-sale follow-up tasks. All of these are secondary to the goals of spending maximum time with the customers and their reseller partners.

Autodesk took a multipart approach to changing the time allocation strategies of sales managers and increasing their attention to coaching. The organization first set a goal for managers' coaching time: four hours per sales rep per month (an hour a week on average per rep). To help managers achieve that goal, the company collaborated with Inside Out Development, LLC to implement a sales manager coaching program called G.R.O.W. (goal, reality, options, and way forward). The program trains managers to establish a goal for each conversation with a sales rep, assess the current selling situation and pinpoint key challenges, identify alternative actions, and choose a course of action for the rep to resolve the challenge. Sales manager job descriptions have been modified to emphasize the importance of effective coaching. Manager compensation has been changed to focus more attention on coaching success. Not all managers have been comfortable with the increased quality and quantity of coaching expected of them. In response, Autodesk has also taken some managers (5–10 percent) out of their managerial roles. Most, however, are achieving the target of four hours of coaching monthly for each rep. And sales reps are noticing the improved focus as well. Survey scores for manager effectiveness in this area are on the rise. As the Autodesk experience confirms, improving manager performance starts with understanding how managers' time allocation choices drive their ultimate effectiveness.[145]

We work with many organizations whose promotion process frequently puts highly qualified technicians into managerial roles where they fail, or at least underperform. Managers, the Human Resources department, and executives all acknowledge the problem. There are many possible causal pathologies: expediency, believing that direct production is all that really counts, concluding that managers really don't matter if organizations have charismatic senior leaders. Sometimes, organizations program the manager's job to fail by promoting the right person but subsequently failing to define the job sensibly or support it effectively.

The goal of this chapter has been to propose a systems approach to defining the major elements of the manager's role. The analysis reflects sensitivity to the assumptions many organizations bring to their conceptions of what managers are supposed to do and how they are supposed to do it. Types of skills, reporting spans, and balancing work and leadership must all be considered. The point is to look at these factors together and consider how they influence each other rather than making decisions that rely too heavily on a single factor (the belief that flatter organizations are ipso facto better organizations, for example). The prize is a role definition that makes it possible for managers to execute the elements depicted in the manager performance model in Chapter Three. Some juggling and balancing are inevitable in the manager's job, but a thoughtful approach to defining the position can make managers' lives easier and maximize their contribution to the organization's strategic advantage.

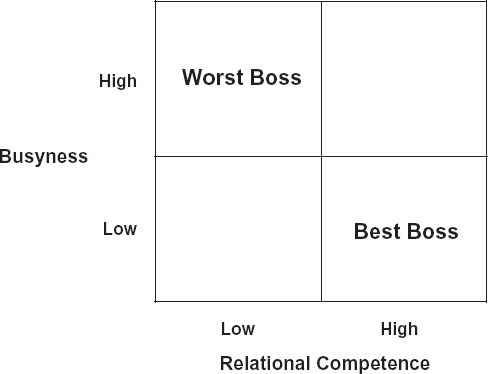

Not long ago, one author (Tom) had the opportunity to hear a panel of millennials describe their actual and ideal work experience. They were in their early-to-mid twenties, most working at their first or second job out of college or graduate school. Someone in the audience asked them to describe their perfect supervisor. A young woman from Korea answered the question by defining both her worst boss and her best boss. Her definition incorporated two simple dimensions, shown in Exhibit 4.4.

Her worst boss stayed too busy doing work to spend time with her. Also, he lacked the relational attributes necessary to make the time he did spend with her truly beneficial. Her best boss had freed himself from production pressure and increased his time available for personal connection. He also displayed the empathy required to coach her effectively. Empathy denotes the ability to comprehend what another person is experiencing and, on some level, to share the other's emotional state without having gone through the same causal events. The best boss represented the paradigm of the offstage manager: available when needed but not hovering; not too busy, either with increasing his own output or closely overseeing work, to have frequent employee contact; and qualified to make the most of the time spent with each individual.

The next step is to explore how managers in a well-structured role system go about executing tasks, developing people, delivering an engaging deal, and energizing change, all while fostering trust and acting authentically. We begin that exploration in Chapter Five.