CHAPTER OUTLINE

Planning Work

Develop Causal Maps

Analyze Results from a Reference Class of Projects

Engage in Counterfactual Thinking

Clarifying Job Roles

Customize Individual Jobs

Recognize Who Can, Should, and Wants to Do What

Make Teamwork Work

Carefully Catalyze Self—Managing Teams

Monitoring Progress

What do the Egyptian pharaoh Cheops and the American psychologist Abraham Maslow have in common? Both are known for their pyramids. Cheops completed construction on his monument, the Great Pyramid of Giza, about 4,500 years ago. He intended to be buried in it, along with all the treasures and supplies he would need in the afterlife. How well he accomplished his intentions we'll never know; grave robbers stripped the Great Pyramid clean of all valuables long before modern archaeologists arrived on the scene.

Maslow's pyramid, which he described in a 1943 paper, has a purpose both loftier and more earthbound. Maslow created his pyramid to depict his conception of the hierarchy of human needs. At the base of his pyramid lie physiological needs—food, water, and air, for example. The pyramid extends upward four more levels, encompassing, in order, the need for safety, belonging, esteem and, finally, self-actualization. The pyramid form captures Maslow's notion that people don't (indeed, can't) attend to a higher-level need until they fulfill the requirements below it. Though he didn't invent the notion of self-actualization, Maslow's pyramid of needs brought it into the forefront of psychological theory. He defined self-actualization as the individual's striving to become more and more what he or she is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.[148]

The decades have largely been kind to Maslow's concepts. Self-actualization remains a critical element in the design of engaging work. We will keep this in mind as we define the manager's role in the execution of tasks. We will also return to the principle established in the first three chapters—that the most effective managers work away from center stage—and see how it applies to the manager's role in the fundamental components of task execution. We will focus on three elements of task execution: planning work, defining and clarifying work roles, and monitoring progress.

Planning in a modern enterprise traces its roots back to methodologies and approaches developed by Frederick W. Taylor and Henry Ford in the early twentieth century. Their legacy includes an array of tools for doing the objective-setting, resource-allocating, and step-defining aspects of planning. Most of us would agree that the tools available for planning work provide more than enough functional support. The problem with planning isn't the tools, nor is it the intelligence of planners. When planning fails (that is, when work doesn't proceed as anticipated and workgroups miss deadlines, production quotas, or quality goals), the problem usually lies not in our tools, but in ourselves.

Psychologists know that we humans give ourselves far too much credit for our ability to perform rational analysis. In fact, our reasoning is fraught with deviations in judgment, cognitive faults that influence how we perceive the world and act on our perceptions. From the list of logical fallacies to which humans (and therefore managers) are heir, three have a direct effect on work and project planning:

The framing effect. Drawing different conclusions or taking different actions from a single set of facts, depending on the how facts are presented or labeled. For example, do you feel better about the use of the same amount of taxpayer dollars for economic stimulus or for bailouts? Which career path would you rather your lawyer daughter pursue, ambulance chaser or public protection attorney?

The illusion of control. Believing that we can direct, or at least influence, events over which we actually have no power. Those afflicted with this fallacy include gamblers who throw the dice harder to roll higher numbers and lottery ticket buyers who choose lucky numbers from among their children's birthdates.

The planning fallacy. Consistently underestimating the time and cost required to complete a task. The planning fallacy seems particularly to affect public servants. It explains why infrastructure projects rarely come in on time and within budget.

These biases influence how managers and other humans instinctively approach planning. We all experience them to a greater or lesser degree. We must recognize and deal with them if we are to succeed at the basic tasks of goal setting, resource planning, and action taking, no matter what competitive strategy we hope to execute. Fortunately, the work of psychologists gives us tools we can use to battle our biases and inject an element of rational thought into work planning.

We can deal with the framing bias, for example, by recasting our language and by using a technique called causal mapping. A causal map (which can take a visual or verbal form—the term map is a metaphor) requires one to identify the true antecedents, actions, and consequences associated with a situation.[149] Reframing calls for a revised description of those facts. Here, for example, is one way of describing a research project:

The client is a technology company that recently went through an initial public offering. The project involves an extensive customer survey to determine how well the organization is serving its business clients. The project will produce $1 million in revenue for the research firm doing the survey. It has a 67 percent probability of generating a 40 percent profit and a 33 percent probability of producing a 40 percent loss. The firm normally wouldn't take a project without a virtual certainty of at least a 25 percent margin. The client organization is known for political infighting, which will make the project difficult to manage and not much fun to execute.

Here's another way to look at it:

The effort would be one of several similar projects the research company has going with this client. If the researchers can establish themselves as the client's provider of choice, they will have a unique understanding of the client's business and access to its data. This will enable the firm to put up barriers to exit for the client, and barriers to entry for competitors, and significantly increase the probability of securing repeat versions of the project. The research firm currently enjoys consistent 30 percent profits on other work for this organization. The relationship manager for this client has a personal goal of 25 percent margins on all of his projects. He made partner largely because of his successful management of this relationship.

The first framing leads to a no-go decision. The second calls for a different conclusion, particularly if the project manager has dreams of following the relationship manager's path to partnership.

If the firm should decide to proceed, the project manager and her team can then go through the causal mapping exercise. Doing so would help them determine how best to minimize the anticipated problems and increase the probability of a mutually satisfactory outcome. After reflection, for example, the team might conclude that the client organization's evolving, unstable, post-IPO culture poses the risk that internal politics could disrupt the project. The response might be to staff the project with consultants who have worked with this client on similar projects before. They know the methodologies required, understand the organization's cultural landscape, and have credibility with the client-side project manager. This combination should help the consulting team anticipate and deal with client politics that threaten to interfere with the project. Similarly, mapping the project would help the consulting team identify where in the project timeline lie the greatest risks that an undisciplined client could fundamentally redefine the project's requirements. Armed with this information—a map of virtual landmines, so to speak—the team might decide to price the project flexibly (time and expense) rather than rigidly (fixed fee) to protect their firm from unexpected scope changes. The team could also plot the key decision-making contingencies on the project time line. By doing this, they could highlight the financial and project quality implications of hitting, or missing, major project milestones.

Reframing and causal mapping take managers and their teams through a clarifying exercise that gets beneath the surface of the framing bias. Approaches like these help managers and their teams to identify the true risks associated with planned work. But even a carefully crafted causal map won't be worth the pixels it's printed with if it fails to produce a realistic estimate of the time and resources required to get work done. Managers also need a way to force reality into the project outcome estimates. One approach, called reference class forecasting, can help managers overcome the unjustified optimism that underlies the planning bias.

Reference class forecasting uses the actual outcomes of a group of similar actions to provide a context for a project under consideration. In effect, it provides an outside view that helps prevent some of the misestimation that often characterizes purely inside views. Reference class forecasting does this by taking the planner through three steps:

Identification of a group of similar past projects from a class large enough to be meaningful but also narrow enough to be comparable with the target effort

Establishment of a probability distribution for the outcome in question (say, profitability, minimization of defects, customer satisfaction) using results data from the reference class

Comparison of the specific project with the reference class distribution, to identify the most likely outcome[150]

The first use of reference class forecasting to challenge the planning bias occurred in 2004 as part of the budgeting process for a public transportation project in Edinburgh, Scotland. The promoter of the project, Transportation Initiatives Edinburgh, had submitted a business case estimating the project would come in at £255 million. With a contingency allowance of £64 million, the total project estimate came to about £320 million in capital cost. After considering a reference class of similar projects, a firm of consulting engineers recommended that the transportation authority raise its estimate to £400 million—a 25 percent increase—if it wanted to have an 80 percent probability of staying within the budget.[151]

Admittedly, most managers aren't dealing with financial numbers this big. Still, the need to budget accurately and then meet the budget remains central to managerial success. Avoiding an £80 million overrun just might save some politician his job. Techniques like reference class forecasting can enable a manager to suspend her natural (and often cognitively flawed) judgments and look for outside evidence that provides a more accurate context for planning.

In applying reference class forecasting to the research project, the team would begin by identifying the consulting costs to complete a group of similar past projects. They might discover, for example, a tendency to overrun consulting budgets by an average of 12 percent on those projects. Therefore, they might decide to raise their cost estimate by 15 percent, factoring in the vicissitudes of this particular organization's unpredictable politics. They could incorporate even more aggressive adjustments if they wanted to make doubly sure not to underestimate costs or overestimate profits.

Techniques like causal mapping and reference class forecasting can help managers overcome framing and planning biases. But what should they do to deal with the illusion of control? Having a carefully crafted project map, complete with all the up-and-down topography of a challenging project, might actually heighten a manager's feeling of influence over circumstances and outcomes. But that confidence might be an illusion, just like thinking that throwing the dice harder will produce more elevens. Managers also need a way to reflect back on real events and to imagine what might have changed the outcomes. One way to do this is to engage in a mind experiment called counterfactual thinking.

Counterfactual thinking simply means comparing what actually happened in a situation with what might have been had past circumstances unfolded differently.[152] It involves reviewing a chain of events, mentally altering something in the action sequence, and imaging how the outcome would have differed. Often, reflecting back and creating "if-only" scenarios can compel a realistic reassessment that challenges an individual's illusion of control. In reviewing the outcomes of similar efforts in the reference class, the research project team might reaffirm a tendency for similar projects to produce cost overruns. A causal map might reveal that falling behind in producing the final analysis and report, and having to scramble to hit the deadline, consistently caused those overruns. Our project manager might start by looking for things she could have done differently. She might order a round of lattes, convene her team, and run through a set of if-only scenarios like these:

"If only we had brought together larger project teams—perhaps we could have gotten more analysis and report production done more quickly. But that would only have added to our project cost and reduced our profitability even further. Plus we would have gotten in each other's way. After all, nine women can't have a baby in one month."

"If only we had gotten the team to work longer hours early in the project so we could have avoided falling behind. But that would only have burned us all out sooner and made us more prone to errors that had to be corrected later. And imagine the cost of all that after-hours pizza."

"If only clients would give us a cleaner file of survey participants' locations and e-mail addresses at the front end of the process. We could get surveys out in the field sooner, spend less nonproductive time correcting survey administration errors, and hit our deadlines."

The manager—and probably the team as well—would likely conclude that the last scenario provides the best solution to the problem. In the process, the project manager would realize that she never had complete control over the outcomes. And so the illusion of control bites the dust. In the future, she would have to work more closely and effectively with others who have influence over project results (specifically, the client's project manager).

Causal mapping, reference class forecasting, and counterfactual thinking complement each other. Reframing and causal mapping require us to challenge the way we look at facts and get beyond the labels that bias our judgment. Reference class assessments force us to look at relevant past outcomes and push us to revise our typically optimistic initial projections. Counterfactual thinking supports our causal mapping by providing scenarios that lead to outcomes different from those actually experienced. Each technique, in its way, reinforces the balanced processing element of manager authenticity—the requirement that a manager objectively analyze all available information, especially facts and insights that challenge assumptions. These approaches require a manager to have sufficient self-awareness (another authenticity element) to recognize and address his own cognitive weaknesses. They also call for no small amount of humility; a successful offstage manager recognizes that overcoming cognitive biases usually requires help from others.

By themselves, techniques like these won't magically turn managers into thoroughly rational thinkers. It will take a few million more years of evolution to accomplish that. Moreover, overcoming judgment biases is a necessary but not sufficient requirement for successful work planning. A manager's approach to planning must be part of a broader philosophy for how work should get done. That approach should acknowledge that the best (that is, the least cognitively biased) planning, like other aspects of the manager's job, happens when managers have a light hand and when they involve others. In the time allocation structure laid out in Chapter Four, planning activities falls into the work process oversight category. Of course, work planning efforts must dovetail with the manager's other responsibilities, especially those associated with people focus. Ensuring that these role elements mesh effectively provides a platform for unit and individual success.

Once the planning is finished, there's work to be done. Decades of research have shown that challenging and gratifying work contributes significantly toward motivating employees to do the jobs required by organizations. The challenge we pose to managers is this: think of employees' jobs as malleable sets of factors, parts to be assembled to fit individual traits and simultaneously meet organizational goals.

As with work planning, managers must overcome a set of cognitive and attitudinal biases as they work with employees to design jobs. These two are particularly relevant:

The actor-observer bias. Tending to attribute our own actions to situational factors and attribute the behavior of others to stable personality traits. If I feel stress before a big presentation, for example, I might ascribe it to my concern that this session will be attended by important clients, a circumstance I use to explain my sweaty palms. Conversely, if I see a colleague showing obvious nervousness before a big speech, I might put it down to his having low self-confidence. I know I'm a great presenter; I'm not so sure about him.

The illusion of transparency. Overestimating our ability to understand others' personal mental states. We believe that we know others better than they know us. In a related way, people tend to think of themselves as having complex and variable personalities, while viewing others as simpler and more predictable. Don't we all think we understand the world better than the world understands us?

These biases threaten to impede managers' efforts to perceive accurately the complex needs and competencies of those around them and to use those insights to craft suitable work roles. Fortunately, managers have at their disposal some cognitive techniques that can help them succeed at their job-crafting tasks and avoid the worst effects of the actor-observer bias and the illusion of transparency.

A customized role never leaps fully formed from the pages of a job description. In fact, just the opposite. Job descriptions are often works of fiction—outdated, oversimplified, sometimes wildly inaccurate snapshots of work realities. Human Resources should provide managers with the formal job specifications for the positions in the unit, but only as a point of departure. Manager and employee must look well beyond the words on the page and consider a variety of dimensions that meet at the intersection of required tasks and individual interests and abilities. At the most fundamental level, the basic elements of a job must align with the interests of the job holder. The several typologies of job components tend to agree that people's work-related interests will fall into the general categories shown in Table 5.1.

By listening to employees talk about what they like and don't like, observing how they go about their work, and perhaps running some experiments (for instance, letting people try small changes in their jobs), an astute manager can help people achieve a fit between their jobs and their work interests. With attention, most managers can figure out which employees display quantitative talent, which are conceptual thinkers, and which are most creative. The same goes for the social elements of work. Whether a person seeks or avoids social contact, displays an agreeable nature or likes to work alone, or has a calm demeanor or is prone to anxiety are all empirical questions. Careful observation and manager-employee cooperation can provide answers and help managers overcome the actor-observer and transparency biases.

In addition to these personal building blocks, managers must consider important dimensions of jobs themselves. One dimension is job demand, the magnitude of sustained mental or physical effort required to execute the basic job components. Job demands are high when the job holder faces frequent challenges and problems: pressure to perform, long task lists, complex role requirements, and emotional stress. Job demand is complemented by job resources: support from teammates, problem-solving assistance from a supervisor, performance feedback (especially recognition for success), and autonomy in how they go about their work. These complement the tangible resources noted in the prior chapter's discussion of the interplay between manager and employee roles. Access to job resources helps people manage large workloads and juggle disparate assignments. They do a better job of handling emotional interactions with customers and reconciling work and home responsibilities. Said another way, job resources help to buffer the effects of work demands, reduce obstacles to performance, and bolster employee engagement in the face of stressful work requirements.[156]

Table 5.1. Individual Interests and What They Mean for Jobs8

If the Employee's Interests Lean Toward Jobs with These Elements: | She'll Get Her Kicks From: |

|---|---|

Technical/engineering | Developing and executing systems and processes |

Quantitative | Manipulating data and explaining things numerically |

Conceptual | Doing research and explaining things theoretically |

Creative/innovative | Inventing something new |

Social/interpersonal | Connecting with others and improving their abilities and performance |

Organizational control | Achieving success by overseeing others |

Influencing | Affecting outcomes through communicative persuasion |

Detailed analysis/execution | Flawlessly implementing existing systems and structures |

Fostering autonomy requires managers to recognize and support individuals' discretion and control in deciding how to do their work. Autonomy differs in subtle but important ways from empowerment. Empowerment has become so common in the business lexicon that it hardly needs a definition, and so cries out for one. When people speak of empowerment, they generally refer to the transfer of power from a manager to an employee. The root words are em (from the Latin preposition meaning into) and power (from the Latin potere, to be able, from which we get words like potent). Empowerment refers to the transfer of a quantity of power from manager to employee. It's a zero-sum power game, where the manager's power diminishes by the amount given to the employee. Jonathan Gosling and Henry Mintzberg recommend that managers go beyond empowerment, "a word implying that the people who know the work best must somehow receive the blessing of their managers to do it."[157]

Autonomy refers to something subtly but importantly different. Essentially, it means self-rule. Its roots are the Greek words auto (self) and nomy (law). Rather than subdividing a given quantity of power, autonomy adds to the total amount of power available to do work. Self-determination is a good synonym. Think of it this way—a royal authority can empower, whereas autonomy requires self-government.

Although the results of empowering and fostering autonomy may seem similar, the dialogue that precedes them is different. The empowerment exchange between manager and employee sounds like this:

Manager: "I have power and I am transferring some of it to you."

Employee: "Thanks, boss."

The autonomy dialogue unfolds differently:

Manager: "You are competent and engaged in your work. You know the results that are expected. How do you want to do your job?"

Employee: "I'll get back to you."

Creating the conditions for autonomy to thrive requires special attention from managers. People can be empowered in small increments, but autonomy is difficult to partition. In general, people either have autonomy in how they do their work, or they don't. Effective autonomy requires the characteristics of the job to complement those of the individual. The work and work environment specifications most critical to autonomy are:

Ease of information access, meaning how readily an employee can obtain the data and knowledge needed to perform his job. For autonomous work, information becomes a critically important job resource. High access means the information is easily available, with low cost of effort and time required to obtain and interpret it. Low access implies the opposite—information is difficult to get and therefore calls for a high investment of effort to acquire and make sense of it.

Employee expertise indicates the degree to which the individual, by virtue of training or experience, has substantial skill and knowledge to apply to the job. In the ideal situation, the employee knows more about the job than does the supervisor. In highly technical research and development positions, for example, researchers often have greater skill and expertise in their specific disciplines than do their equally well-educated but less-specialized supervisors. If the employee doesn't possess expertise at least as great as that of the manager, autonomy will be ineffective and ultimately frustrating for both.

Task independence indicates the interconnectedness among jobs. Highly independent jobs (as with a sales group in which each rep has a different product line) afford more opportunity for autonomy than jobs that function more interdependently (for instance, two programmers writing complementary code for the same program).

Task variability speaks to the breadth of activity and the frequency of exceptional situations built into a job. Highly variable jobs (like those typical of lawyers and consultants) benefit from autonomy. In contrast, people whose jobs consist of relatively routine tasks that don't vary much from day to day (office receptionists, for example) gain little from autonomy.

Work process freedom, referring to the degree of informality, creativity, and improvisation available in a job. Fewer rules, regulations and stipulations suggest an opportunity for autonomy. Conversely, high formalization (for example, in a position requiring rigid safety or quality procedures) limits an individual's freedom to exercise discretion on the job.[158]

In effect, autonomy serves two functions: it is a feature of a rewarding job and a reward unto itself. Although autonomy clearly has value to employees, it isn't free. It requires a cognitive investment and brings responsibility for outcomes. Conversely, it can moderate the relationship between the accountability burden that comes with self-determination and the emotional stress brought on by the weight of obligations.[159] Effectively autonomous employees also confer a benefit on the organization. They enable managers to spend less time performing and closely overseeing work and more time thinking about how to improve work processes, build networks, and craft and deliver appealing individual deals for employees. In effect, employee autonomy moves managers away from the Widget Wizard role structure and toward the People Powermeister form.

The effects of job demands and job resources will naturally vary from person to person. This is where an additional element, individual disposition, enters the equation. In this context, disposition refers to the tendency for people to be either proactive or passive. Proactive people believe they can control circumstances and create change in the work environment. They adopt what psychologists call a "promotion focus," meaning they exhibit persistence, motivation, flexibility in the face of challenges, and, generally, satisfaction with their work. They tend to be extroverts, seeking social contacts and looking for excitement. Managers will recognize them as the optimists who concentrate on winning and want to receive rewards for their success. Passive employees, in contrast, tend to view opportunities for change as beyond their personal scope and ability. They respond to circumstances as they occur and hope for the best. They display vigilance, risk-aversion, and loss-avoidance.[160]

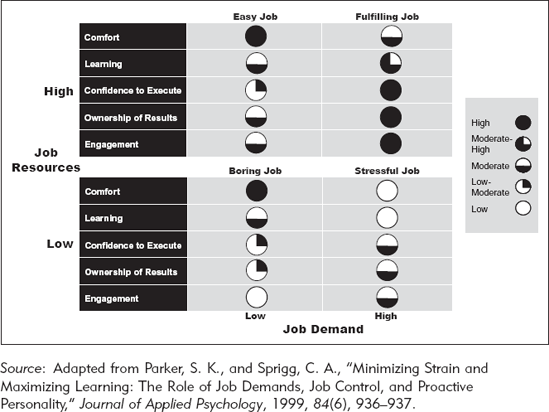

So the full equation contains three factors: job demands, job resources, and personal disposition. The interaction among these three elements yields outcomes in five categories:

Comfort measures the contentment that people experience at work, the absence of anxiety, tension, and worry that are beyond their ability to handle; high comfort means stress is manageable and often energizing, but not absent.

Learning means the opportunity for people to acquire and use the abilities necessary to perform demanding tasks (to build human capital, in other words)

Confidence to execute (which psychologists call self-efficacy) goes to the employee's belief that he or she has the knowledge and skills necessary to get a specific job done well.

Ownership of results refers to the strength of an individual's sense of responsibility for the performance of the production process.

Engagement means the emotional, rational, and motivational connections people have with their organizations and their work.

The chart in Exhibit 5.1 shows how these factors interact for people who have a strong inclination to influence their work environments (that is, people who exhibit high proactivity, flexibility, and motivation to succeed). Note the cluster of dark bullets in the Fulfilling Job column. For these employees, confidence in their ability to execute, ownership of outcomes, and engagement all peak when their managers take the time to ensure that competencies, roles, and resources come together to give them high control over a challenging job. Alternatively, given low control or less-demanding work, a naturally proactive person will generally reach lower levels of mastery, achieve lower levels of confidence in personal effectiveness, assume less ownership of results, and feel less engaged. Efforts to achieve self-actualization will be thwarted.

Job content also plays a role in determining how well employees understand and respond to the link between their work and organizationally valued outcomes. For example, ensuring that people have periodic contact with the beneficiaries of their efforts can have a powerful effect on effort and performance. In one study, researchers introduced a group of university fundraisers (the folks who call during dinner to ask you to contribute to your alma mater) to one of the scholarship recipients who had benefited from their money-raising success. He told them how much he valued their effort and how helpful the scholarship money had been to him. A month later, the research team measured the performance of the fundraisers over a week's time. They looked for differences among three groups: a group that had met with the student, one that read a letter from the student, and one that had no contact at all. They found that the fundraisers who had spent time with the student more than doubled their per-caller minutes over what they had spent before meeting him. They also secured almost three times as much money as they previously had. The researchers concluded, "Merely interacting respectfully with a beneficiary of their work enabled them to maintain their motivation, as observed in their persistence behavior and objective job performance."[161]

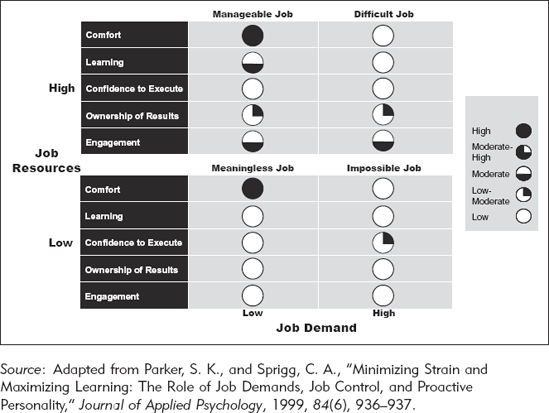

Exhibit 5.2 shows the same array of job factors for more passive employees, those who focus their attention on preventing downside events. They function best with low job demands and high control (the Manageable Job depicted in the left-hand column). Too much challenge causes discomfort and tension. Even given their relatively passive personalities, however, these employees learn more, take greater ownership of results, and exhibit higher engagement when they have direct influence over the circumstances of work.

The common factor for the most rewarding work, regardless of individual personality, is control over results. Jobs structured to incorporate this element, and the other elements depicted in the exhibits, can provide the skill development, decision input, career advancement, and work opportunities that people crave. Research in the workplace (as with one analysis conducted in the call centers of a British financial institution) confirms that this combination of factors also produces high performance.[162] Call center jobs, the research confirmed, can be stressful and unfulfilling. Astutely managed companies, however, can bolster the resource side of the equation and improve both individual performance and customer satisfaction.

For example, consider the case of Zappos, the quirky online retailer. Zappos has probably moved as far from the call-center-as-electronic-sweatshop as it's possible to go. In fact, Zappos is such an appealing place to work that it debuted at number 23 on the 2008 Fortune list of the best companies to work for, the highest newcomer ranking in the history of the list.

The Zappos approach shows how job design can support a customer focus strategy. The call center rep's job structure lies at the center of the company's service model. The organization begins by taking potential hires through a careful screening process that eliminates the shy, the egotistical, and the unfunny. They want people from the proactive end of the personality spectrum only. "We do our best to hire positive people and put them in an environment where the positive thinking is reinforced," says Tony Hsieh, Zappos chief executive.[163] That environment is script-free and freedom-rich. The principal job of front-line reps is not just to close a sale, but also to please the people who call in to order.

They are trained to encourage callers to order more than one size or color, because Zappos pays for shipping both ways. They refer callers to competitors when Zappos is out of stock. But most important, their jobs are constructed to let them use their creativity and their imaginations to delight customers. In one case overheard by a magazine reporter, a customer complained that her boots from Zappos had begun leaking after almost a year of use. The rep not only sent out a new pair, in spite of a policy that used shoes can't be returned, but also mailed the customer a handwritten thank-you note.[164] Rumor has it that a Zappos call center rep once spent six hours on the telephone with a single customer. This kind of initiative, combined with a job structure that affords the freedom to exercise it, captures what Zappos means by WOW: "To WOW, you must differentiate yourself, which means doing something a little unconventional and innovative.... We are not an average company, our service is not average, and we don't want our people to be average. We expect every employee to deliver WOW."[165]

Zappos managers are also encouraged to spend 10 to 20 percent of their time with team members outside the office. This intensive interaction enables managers to get to know their team members far better than they can in the context of work alone. CEO Hsieh says that when he confers with managers after they've taken their team members on an outing, they talk about improved communication, higher trust, and budding friendships. "Then we ask, 'How much more efficient do you think your team is now?'" Hsieh says. The answer? "Anywhere from 20 percent to 100 percent."[166]

As the Zappos example suggests, designing engaging jobs doesn't have to be limited to high-end knowledge work. Granted, research into engineering positions suggests that knowledge workers sometimes have more latitude than others to alter the boundaries of their roles by taking on unassigned tasks, teaching new skills to others, adding coworkers to their networks, and participating voluntarily on teams. But a study of hospital cleaning staff showed that, despite having a relatively prescribed set of tasks, even custodial workers can craft their jobs individually. One of the groups analyzed stayed with the standard job description, which involved little interaction with patients and other staff. They reported that they disliked cleaning in general, judged the required skill level to be low, and had little willingness to engage with others or alter job tasks. They saw their job as cleaning—nothing more. Members of a second group went out of their way to interact with patients, visitors, and others in their unit. They made an effort to add tasks and to time their work to coordinate with others. Cleaners who crafted their jobs saw themselves as playing an important role in the experience of patients.[167]

Or take the case of nurses, who can craft their jobs by creating expanded opportunities for interaction with other care providers and with patients' families. To quote the researchers from one ethnographic study, "The nurses acted as job crafters by actively managing the task boundary of the job to deliver the best possible patient care. By paying attention to the patient's world and conveying seemingly unimportant information to others on the care team, nurses re-created their job to be about patient advocacy, rather than the sole delivery of high-quality technical care."[168]

Employee and manager both have roles to play in customizing jobs. In the words of one pair of psychologists, "People are not passive receivers of information from their work environment, but rather active in interpreting their jobs, and consequently in shaping their jobs."[169] Another researcher says that "Not all employees are motivated to fulfill needs for control, positive image, and connection at work. Individuals who look to fulfill these needs at work likely will look for opportunities to craft their jobs in ways that allow them to meet their needs. Others may find that these needs are met elsewhere in their lives."[170] Only a direct manager—by empathizing with an employee's individual work needs, mediating within a work group to craft a set of personalized job demands, and ensuring that job roles support the successful execution of unit and enterprise strategy—can help an individual make the multidimensional matches reflected in Exhibits 5.1 and 5.2.

In real life, few people sit squarely at one end or the other of the proactive–passive spectrum. As we saw in Chapter Two, most people experience some level of conflict as they choose between dominating and deferring. We want to lean far over to grab the brass ring, all the while holding tightly to the carousel horse's neck. Likewise, jobs rarely fall cleanly into either the "easy" or "impossible" categories. Managers must deal with ranges of factors for both people and their jobs. How can a manager get an accurate understanding of an individual's disposition and overcome the actor-observer and transparency biases? Research suggests that good judges of people do three things well. First, they create situations in which people manifest relevant clues to their personalities. Then, the skilled judges interpret those clues accurately and put them to use.[172] Table 5.2 summarizes how a manager might perform this sequence.

Good judges of personality have predictable traits. They tend to display:

Trustworthiness and fairness. They make the people around them feel comfortable in being their authentic selves, which gives a manager access to accurate information.

Interpersonal awareness. They have a heightened ability to acquire and interpret clues fully and accurately, which helps them recognize and assess the insights they obtain.

Sense of humor. They have a relaxed style that puts employees at ease, an advantage in eliciting information on how people naturally behave.

Intelligence and intellectual complexity. They have cognitive attributes that give them an advantage in interpreting clues and crafting jobs that accommodate individual personality.

Social skills. They tend to be agreeable and extroverted, meaning they genuinely enjoy the interactions that produce personality information and have an interest in learning about the people around them.

Table 5.2. Three Steps to Understanding the Individual Personality

Step 1—Observation

Step 2—Interpretation

Step 3—Action

Manager question—How can I get information on what this person is about?

Goal—Enlarge the number of relevant clues and bits of insight

Possible tactics:Experimentation—Create situations for traits to appear. If these are true experiments, then performance failure will be treated as information, not a criterion for judgment

Observation—Watch how people handle their work, what energizes them, their demeanor, their interaction with others, their language, even their dress and appearance

Discussion—Talk to people and listen to them tell about their work. Extend observations over the long term, to improve quantity and reliability of information

Manager question—What is the significance of what I've learned about this person?

Goal—Make sense of the information to draw correct conclusions about employee personality

Possible follow-on questions: Do they act proactively or passively?

Do they display psychological flexibility?

Look for consistency—do patterns emerge? What behaviors are associated with what situations?

Compare across team members—what similarities and differences do you see?

Manager question—What actions should I take given the interpretations I've made?

Goal—Put the information to use for the benefit of the individual and the organization

Possible actions: Job customization—craft a role that works for the person, the team, and the company

Place the job in the right context—individual versus team work structure, for example Support the job with the right employment deal

Flexibility. They are willing to suspend premature judgment and interpretation (the application of balanced processing), which increases the probability that their ultimate judgments will be correct.

Self-awareness. They understand their own personalities and so have a foundation for empathy and a frame of reference for interpreting the behaviors of others. Like balanced processing, self-awareness is an essential element of manager authenticity.

In short, they act authentically, observe astutely, and interpret accurately. Mostly, they are good listeners, and much more.

Sometimes, a team structure best meets the job-related needs of individuals and the strategic requirements of organizations. Structuring work in teams has become a ubiquitous artifact of organizational life. Effective team collaboration, says organizational and evolutionary psychologist Nigel Nicholson, is "widely attributed to be the single most important predictor of successful enterprise, and group breakdowns one of the most common causes of failure."[173]

Rarely do organizations dedicate themselves as thoroughly to a collaborative way of working as does high-tech icon Cisco Systems. Cisco, which makes the routers and switches that link networks and power the Internet, pursues a strategy relying on product differentiation bolstered by operational discipline. Connecting people and communities isn't just the competitive goal—it's also how the company does its work. Cisco pursues this strategy by arraying its units functionally. In the words of Randy Pond, Cisco's executive vice president of Operations, Processes, and Systems, "Cisco is the largest functionally organized company that I know of."[174] Functional organizations, which separate themselves into discrete areas like R&D, engineering, manufacturing, sales, and product development, sometimes have difficulty getting new products developed and delivered to the market. The organizational stovepipes are often so self-contained and impermeable that cooperation in the interest of a broader initiative—such as combining research expertise with product development insights—becomes next to impossible. That would be fatal for a company like Cisco, whose business relies on collaboration that drives innovation and new product introduction. So, rather than change to a fundamentally different structure (one based on lines of business, for example), the company has instituted an intricate system of committees made up of executives and managers from various functions. At the top of this structure are twelve councils, with an average of fourteen people each. Councils take charge of markets that could reach $10 billon in revenue. The small business segment, comprising companies with fewer than a hundred employees, is an example. Below the councils are some forty-seven boards, also with about a dozen members each. A board concentrates on market opportunities in the $1 billion neighborhood. Finally, working groups, small temporary teams that concentrate on individual projects, support the board and council structure.[175]

If this arrangement sounds like a matrix—point taken. Matrix structures are hardly new, and they don't come without complications. A matrix arrangement brings reporting ambiguities, as people try to figure out whether they answer mainly to their nominal manager or to a project manager for the team they've joined. It can also cause fights between managers as they duel for resources and jockey to position their projects at the head of the organizational queue. According to Nigel Nicholson, "The injection of matrix forms into traditional hierarchies typically fails because the pull of functional identity overrides the requirements of interdisciplinary collaboration."[176]

Interdisciplinary collaboration is precisely what Cisco needs to be the innovator it wants to be. So what does this all mean for managers and employees and their work? Managers must begin by deploying assets exceptionally well. The key assets under management are information and technology. Moreover, given a matrix structure, managers must do their asset deployment, as well as their coordinating and cultivating, in a focused but infrequent way. You might call it punctuated management—intense and vital contact between managers and employees, in an episodic form.

In another sense, the Cisco structure calls for a redefinition of line management. In this way of working, project managers oversee the execution of tasks by paying attention to:

Outlines. Negotiated agreements between employees and managers, governing how work will get done

Time lines. Agreed-upon calendars for the production of results

Deadlines. Clear understanding of the final goal and its due date

Telephone lines. Technology support to connect individuals and groups

This approach to configuring work calls for an extraordinary level of trust among managers and between managers and employees. Managers must have confidence that employees who are out of sight (except in a teleconference) are nevertheless working to their productive maximums. In effect, managers must fight against the illusion of control, since there's no way they can closely direct people who have many bosses. Employees, in turn, must trust their managers to perform a conscientious and comprehensive assessment of their work results, because those results will often be delivered to someone other than an employee's formal supervisor. Managers who share resources, including the human capital of employees in common, must negotiate for the use of those resources in good faith, with the greater good of the organization always forefront in their minds. As Cisco CEO John Chambers says, leading only the people reporting directly to them is not how Cisco managers should behave: "That's not what cross-functional leadership is about.... Whoever serves on each of these councils and boards and working groups, from each functional group, has to be able to speak for the whole group. Not go back and ask permission, but has to be able to speak for the group."[177]

Cisco would probably admit that the roles of supervisors and managers in its technology turbocharged matrix are still under construction. After all, laying a matrix on top of a functionally oriented pyramid calls for substantial focus and energy. For this reason, the council and board structure has taken from 2001 to 2009 to become fully effective. No doubt managers still struggle with player-coach responsibilities, and spans of control probably need to be worked out for various managerial positions. But one thing is clear: Cisco has decided that the collaborative, punctuated leadership and management encouraged (in fact, required) by its matrix structure are critical to acquiring and defending a differentiated product position. The competition is no pushover—companies like Hewlett-Packard and IBM aren't likely to let Cisco win without a fight. An innovative organizational architecture, with all it implies for leaders and managers at all levels, represents a key weapon in Cisco's competitive arsenal.

Many organizations want to foster team-based collaboration without the complexities of a matrix approach. Some choose instead to institute self-managing teams. Like matrix configurations, self-managing teams are not new. And, like organizational matrices, they are easy to get wrong. Especially in organizations with cultures that encourage heavy manager direction or the opposite, unfettered individual initiative, autonomous teams can prove more frustrating than effective. The paradox of managing effectively from the sidelines has its quintessence in how supervisors build and work with self-managing teams.

A study done in the customer services division of Xerox Corporation explored the kind of manager behaviors that enhance or hinder the performance of self-managing work groups. Like Cisco, the modern incarnation of Xerox has chosen to pursue an innovation-intensive focus on product differentiation. Anne Mulcahy, former Xerox CEO, ensured that research and development would remain a continuing priority of the company. She is on record as emphasizing that Xerox is also dedicated to delivering a great customer experience. She came by her customer focus naturally, having started with Xerox as a sales representative in 1976.[178] If anything, her successor, Ursula Burns, is working to accelerate the company's progress toward higher revenue through tighter customer ties and more profitable products and services.[179]

At the time of the study, the Xerox service organization was divided into nine geographical areas that were in turn subdivided into districts and subdistricts. A manager headed up each subdistrict, which had twenty to thirty technicians apiece. Technicians worked in teams of between three and nine members. Their jobs were to respond to customer calls about machine breakdowns and visit customer sites to perform preventive maintenance. The study looked specifically at two forms of manager involvement with the teams: team design and manager coaching.

Thoughtfully designing a self-managing team involves a broad array of dimensions. The Xerox research team, headed by Dartmouth professor Ruth Wageman, looked at such design elements as:

Clarity of purpose. The team knows what it is supposed to accomplish.

Stability of team membership. The team has a consistent membership of between four and seven members who bring diverse task-relevant skills to the job.

Task interdependence. The team's work requires a cooperative effort in order to be successful; work better done by individuals is excluded from the team's charter.

Meaningful goals. The team has objective performance targets that are challenging but achievable.

Process agreement. Team members agree about how they should work together, how much collaboration they need, how they should seek advice from other teams, and how much experimentation they should do with work procedures.

Supportive reward system. Managers reward success, and 80 percent or more of the available rewards are contingent on team rather than individual performance.

Resource availability. The team has access to plenty of information (such as trends in customer feedback and machine performance), training, and physical assets (tools and materials, for example).[180]

Different styles of manager coaching encompassed such elements as:

Informal rewards and cues. Rewarding the group for problem solving and signaling, by spending time with the group rather than with individuals, clarifying that the team has responsibility for managing itself

Problem-solving consultation. Broadening the group's repertoire of solution skills through teaching and facilitating troubleshooting sessions

Assistance with team process. Surfacing and helping the team deal with intrateam disagreements and conflicts and reinforcing that specific individuals, or the manager herself, are mainly responsible for overseeing the team's work

Intervening in tasks. Dealing directly with customers without involving the team

Identifying team problems. Pointing out concerns or shortcomings in team performance[181]

The research team classified the first two forms of manager coaching—providing autonomy-reinforcing rewards and building the group's toolkit of skills—as "positive coaching." Conversely, two other elements—intervening in tasks and pointing out the team's problems—tended to reduce the team's sense of collective responsibility. The researchers labeled these "negative coaching."[182]

The Dartmouth group assessed team performance by looking at such factors as customer satisfaction with service; parts expense; time to respond to customer calls and complete repairs; and machine reliability. The team came to a conclusion that at first seems surprising but makes sense on further reflection: no form of manager coaching improved team performance. The coaching elements that the researchers called positive coaching were associated with overall levels of successful team self-management and quality of group process. But they had no significant correlation with achievement of objective performance standards. In contrast, teams that were designed well (had a clear statement of purpose, consistently worked interdependently on tasks, executed a strategy of sharing successful practices, and benefited from a team-oriented reward system) did perform better.[183] The takeaway for managers: create the architecture for self-managing teams carefully and then honor the concept of self-management. Be a good manager by providing information and material resources. Be a good leader by providing direction, establishing clear and challenging goals, helping when the team needs to get over process hurdles, and rewarding the team when it succeeds—but only as a group. Otherwise stay out of the way.

Monitoring work progress and results, the third dimension of the manager's task-execution responsibilities, should directly reflect the logic established in work planning and job role clarification. In a product-differentiation strategy, for example, innovation matters. Therefore, the manager of the R&D unit will pay special attention to metrics indicating successful new product commercialization. Individual and team work flows will be structured to focus attention on product development, and customized jobs will provide for the free-flowing creativity necessary to inspire innovation. With a customer-focused retailing strategy, buyer satisfaction and repeat purchasing drive success; measures of these factors will rise to the top of the manager's scorecard. Store schedules will put the best salespeople on the floor during peak periods of customer flow. Sales jobs will be streamlined so people can pay close attention to buyer needs without other distractions, thereby increasing the customer satisfaction and sales-per-customer measures. If low-cost product and service delivery define an organization's strategic intent, managers will pay attention to measures that indicate productivity and minimization of waste. Managers will ensure that job demands and resources are balanced to make high-output work sustainable.

Monitoring work results brings the risk of falling victim to a particular measurement fallacy. We call it the lost-keys-under-the-streetlight fallacy—the tendency to measure what's easy to quantify, rather than what matters, like the man searching under a bright light for the keys he dropped three blocks away. When it comes to remaining vigilant about the streetlight measurement tendency, few organizations face greater challenges than do call centers. They typically monitor a dizzying array of numbers, from call waiting time to call resolution time to customer attitudes, with variations and permutations of many metrics. Some yield insights, while others are merely easy to capture.

For the most part, measures fall into one of two categories: call handling efficiency and customer satisfaction. In a study by the International Customer Management Institute (ICMI), respondents said that the most common service measure is percentage of calls handled within twenty seconds. The goal is typically 80 percent.[184] Only about 40 percent of call centers measure first-contact resolution (FCR), a more important indicator of customer service performance. FCR has links with enhanced customer satisfaction, greater agent satisfaction, increased revenue generation, and (surprise) lower operating costs.[185]

The Philippines-based call center organization eTelecare has taken measurement beyond call handling time and even beyond FCR. Managers pay especially close attention to cost per resolution. This measure incorporates the cost of call center operations required to handle a call (including subsequent calls to take care of the same problem) as well as the expense associated with dispatching the call for further resolution steps. In handling technical support for a major U.S. electronics manufacturer, the company reduced cost per resolution to 40 percent less than the client company had achieved in its own U.S. call center. eTelecare delivered a cost per resolution 30 percent below U.S. call center outsourcers and 16 percent less than the electronics company's call center operation in India.[186]

The company's success demonstrates what can happen when an organization achieves clarity about its strategy, measures what matters to clients, and then supports the strategy with a supervisor role that makes human capital a competitive advantage. Supervisors at eTelecare invest an hour a week coaching each employee, on top of the time they spend monitoring employee performance. They also put at least 10 percent of their time each week into developing process improvements.[187]

eTelecare has garnered a long string of awards that attest to the high-quality service its CSRs provide. The organization won a 2009 customer relationship management award from Customer Interaction Solutions magazine. The company has also received multiple Best Outsourcer awards at the International Call Center Management Conference. As founder Derek Holley says, "Our clients don't just come to us because of our cost advantage relative to their in-house U.S. operations, they want to be sure that we will deliver superior service to their customers. They stay with us because they simply can't replicate our service levels in their own operations."[188]

What seem like the most pedestrian of manager responsibilities—planning work and getting it executed—turn out to comprise a complex set of intellectual and psychological requirements. Performing this role calls for managers to be insightful observers of human personality and behavior—to be field researchers in their own tribes, so to speak. Using the information they gather from living with their work groups, high-performing managers will:

Not just use planning tools effectively, but also challenge the intellectual biases and perceptual shortcomings that undercut sound use of those tools

Not just ensure fair workload distribution, but also involve individuals in crafting their jobs and deciding how their work can best be accomplished to achieve strategic goals

Not just treat all employees equally well, but also go beyond equity to individual focus, understanding and responding to the subtle differences in what drives different people's work involvement and engagement

Use metrics that take the focus away from effort and instead emphasize results that matter to business success

Not empower employees, but instead create the circumstances for them to exercise effective autonomy

Start the week by asking, "How can I do less hands-on work and spend more time helping the team perform better?"—rather than beginning with a to-do list laden with direct output tasks

The work planning, execution, and monitoring concepts described here reinforce the notion that an effective manager does his work offstage. Certainly that's true at Cisco, where managers occupy the nodes in a complex web of collaborative activities. The workings of the Cisco matrix emphasize the importance of extra-unit outreach, described in the manager role discussion of Chapter Four. The success of eTelecare reminds us that managers whose roles let them spend the majority of their time and attention building employee skills and enhancing work processes can significantly accelerate organizational performance. They can succeed in doing so, however, only when their spans of control are circumscribed and their responsibility for direct production is significantly limited.

Effective offstage managers must become comfortable in ceding to others significant authority over the planning and execution of work.

They lead in ways that reflect the demands of our evolutionary roots: they equip us to do our work well, and then leave us alone to do it. This requires them to build a strong foundation of mutual trust with employees and to display authentic humility in challenging their own planning and control biases. The payoff of these approaches to planning work, defining jobs, and monitoring results is competitive advantage. Done right, they also make employee self-actualization a likely outcome, rather than a fortunate accident.