CHAPTER OUTLINE

Coping with Imposed Change

Embrace Positive Change

Handle Adverse Change

Choosing to Change

Enhance Individual Creativity

Build Adaptable Teams

Sustaining Engagement

Foster Well—Being

Ensure Performance Support

Reinhold Niebuhr, American theologian and social critic, offered his serenity prayer as a way to think about circumstances and our power to change them. His words have become familiar: "God, give us grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things which should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other."[253] Useful as this guidance is, however, it doesn't cover every form of change we face. It ignores the imposed alterations, modifications, and deviations—some pleasant, many not—that take place because of factors outside organizations' control.

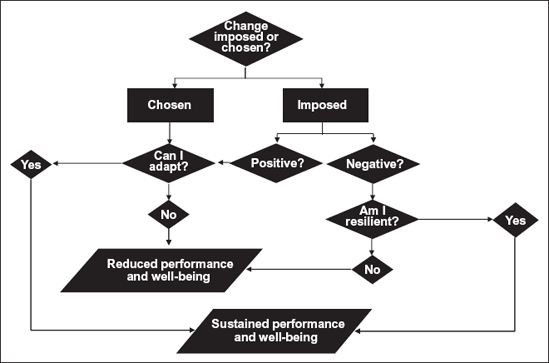

Figure 8.1 shows the paths of change, beginning with the two different change forms:

Chosen change, we assume for this discussion, will have a positive intent. However, it may also require employees to adapt in some way. Imposed change typically brings stress and challenge, requiring people to adapt if events produce positive effects, and to exhibit resilience if the transition is more difficult. By adapt we mean to modify actions and attitudes to make the most of new circumstances. If those circumstances are harmful—positions eliminated, support resources reduced, workloads increased—then adaptability is not enough. Under those conditions, employees must be resilient. They must withstand the shock of change, adjust to new realities, and rebound from the experience to perform as strongly as before, or even more strongly. Whether change is imposed or actively pursed, positive or negative in its ultimate effects, employees will inevitably need to respond in some way. For the outcomes of change to include sustained well-being and continued or improved performance, managers must take steps to build the organization's change capability. They do this by helping to build each employee's change readiness and capacity to withstand uncertainty and turmoil.

Economic pressures, new competitors, other companies' novel product and service offerings, technologies that promise efficiency improvements—these outside forces and many more can force executives to conclude that something about business strategy, production processes, or resource allocation must change. As Figure 8.1 suggests, how people respond to the challenges of externally imposed change will depend largely on whether their adaptability or their resilience is called upon, and on how they respond to that call.

When organizations respond to external forces by resolving to change, they need to carve out specific roles for line managers. By doing so, they improve their chances that employees will not just accept, but also embrace, the new ways of working. One study, conducted by a team of researchers at Troy University and Auburn University, looked at how health care workers adapted to the introduction of new record-keeping technology. The team studied how nurses and other workers responded to the transition from using laptop computers for patient care documentation to using hand-held devices. Nurses also had to move from printed patient care plans to automated clinical planning software. The nurses hadn't sought these changes. From their standpoint, the new ways of working were imposed by the organization. From the organization's standpoint, the potential benefits were clear. Nurses would become more efficient, improving the continuity of patient care and reducing the expense associated with copying and pushing paper.

The researchers found that individual adaptability in response to new work-altering technology depends on the degree to which managers:

Ensure that technology provides work support and improves performance. When a job becomes more interesting and its mastery more fulfilling, individual performance improves. Work process changes that add to job enrichment and mastery therefore contribute to performance. Managers needed to make sure that the new devices made jobs easier, not harder, and workers more productive, not less so. Change that brings out what is essential and important about the job contributes to success. New ways of working that distract workers from what seems most interesting and involving about their work does the opposite. We know from our discussion of job content that challenging and demanding work, if properly supported, produces a host of positive effects. New, efficiency-enhancing technology can provide such job support. Conversely, if technology reduces job complexity and challenge to the point where work becomes simplistic, laden with minutiae, or devoid of challenge, employee engagement may be eroded. No nurse wants his or her work to become more about pushing buttons than serving patients.

Involve workers in the introduction of new technologies. Involvement means giving the affected populations some say about when and how technology would be introduced. It requires managers to seek employees' advice on how employees, patients, and customers might respond to new ways of doing things. Control, in turn, increases the likelihood that workers will accept modifications in how they do their work. Also, involving workers who have direct influence over production and service delivery will build their confidence that new technology will enhance (and not degrade) their ability to serve patients and customers effectively. The goal is to give people substantial control over their workplace destinies. Doing so increases feelings of autonomy, self-efficacy, and mastery.

Following a circular path, self-efficacy itself promotes the adoption of technological innovation. According to Albert Bandura, "Early adopters of beneficial technologies not only increase their productivity but can gain influence in ways that change the structural patterns of organizations.... Beliefs of personal efficacy to master computers were predictive of early adoption of the computerized system. Early adopters gained more influence and centrality within the organization over time than did later adopters."[254] The engagement path progresses like this: involvement in change efforts boosts control and engagement, which increase self-efficacy, which fosters rapid adoption of job-enhancing technology, which increases engagement-driving connections with the organization. A virtuous circle, if there ever was one.

Clarify individual roles within the affected organizations before new technology comes on the scene. Role clarity goes to the heart of rational engagement. It forms an essential connection between individual work and organizational success. Ambiguity about roles and lack of clarity about contribution to unit and enterprise success provoke negative reactions to technological changes. Conversely, workers who have a better line of sight between their jobs and the success of the organization show more inclination to embrace changes of all kinds. Their comfort with change becomes all that much stronger when their managers help them envision a positive effect on product and service outcomes.[255]

Findings like these have been replicated in other circumstances where organizations responded to external conditions by introducing change intended to improve work processes. For instance, researchers from the University of Queensland in Australia conducted a two-year study of organizational changes in the Queensland Public Service (QPS) department. QPS undertook the organizational restructuring in response to recommendations from an independent external review body. The goal of the changes: to increase program efficiency while maintaining high-quality service for external clients. The QPS experience provides a good example of change that originated externally but had a prospectively positive result. Over the course of the two-year analysis, the researchers found that employees with high self-efficacy experienced greater job satisfaction over the period of change in spite of increases in three sources of change-related stress: role ambiguity; higher workloads; and what the academics called "change-related difficulties" (disruptions to workflow, loss of personnel, and concerns about long-term career prospects). They said, "Change-related self-efficacy was an important buffer of three change-related stressors in the prediction of employee adjustment, 2 years after the organizational change process was initiated."[256]

The consistent pattern across these examples is the effort that companies made, in part through supervisors and managers, to increase employee adaptability. Involvement in change efforts gives employees an element of control, which makes change seem less threatening and makes accommodating it less daunting. Managers can increase employees' sense of security and stability by keeping them informed of progress and helping to preserve clarity about their roles and contributions. Perhaps most important, managers can build employees' self-efficacy by the way they recognize and reinforce strong performance during periods of uncertainty. The secret to adaptability is preserving whatever shouldn't be changed—successful techniques, strong inter-employee relationships, team structures that work—while making the changes that will produce genuine improvement. On this point we agree with Jonathan Gosling and Henry Mintzberg: "Change cannot be managed without continuity. Accordingly, the trick ... is to mobilize energy around those things that need changing, while being careful to maintain the rest."[257] Sounds like something Reinhold Niebuhr might say.

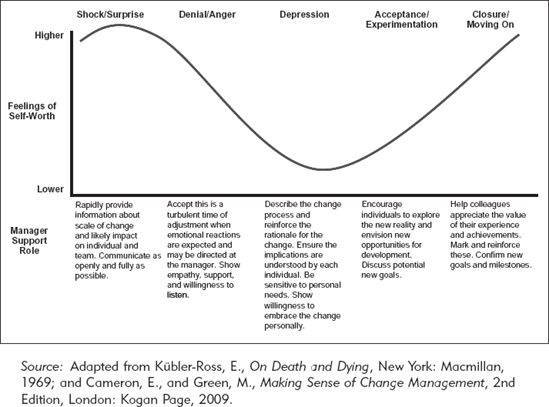

Anyone who has lived through a downsizing knows that external factors can sometimes lead companies to make painful changes. This kind of change is represented by the imposed negative change/resilience path shown in Figure 8.1. Organizational and clinical psychologists have had ample opportunity to study the impact of downsizing and other adverse changes and stressful events over the last forty years. Building on the initial work on grieving by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, researchers have plotted the journey that employees take through the coping process. In the work context, the stages of adjustment begin with shock/surprise and progress to denial/anger, depression, acceptance/experimentation, and closure/moving on. Individual feelings of self-worth cycle up and down during the process, as Exhibit 8.1 shows.

For employees to feel a commitment to the organization during times of adverse change, they must understand the context and business case for change. The case needs to be made at two levels. From those at the top of the enterprise, employees typically expect to hear about the rationale for a major business change, the external pressures that have led to the change, and the consequences associated with not changing. However, they prefer to learn from their managers how the change is likely to affect them personally. They want to hear from, and be heard by, someone who knows them and is familiar with their day-to-day work lives.

The manager support roles outlined in Exhibit 8.1 provide a roadmap for guiding people through the process of difficult change. But employees need something more to deal with trauma in a way that minimizes its emotional and cognitive effects and preserves performance. That additional element is resilience. Resilient employees emerge from traumatic experiences with at least as much vitality as they had before the bad times occurred. Resilience incorporates adaptability, but goes further. Adaptability enables people to change as circumstances require. Resilience provides the capacity to handle more profound, more disruptive change and to emerge from the experience with strengthened resolve and greater performance capacity.

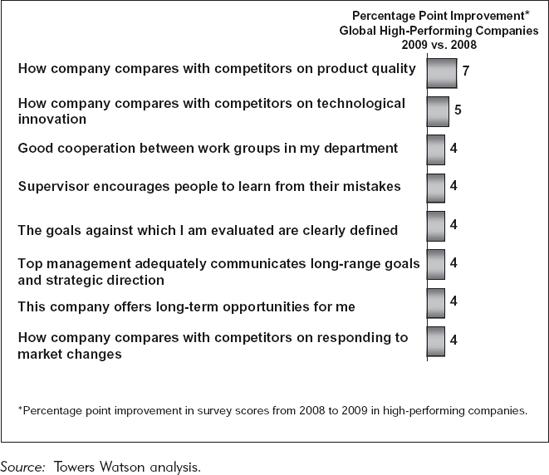

As with virtually all psychological traits, resilience has a dispositional component. People who display resilience have what one team of researchers called "a dynamic psychological capacity of adaptation and coping with adversity."[260] Proactive people, those who seek challenges rather than avoiding them (we met them back in Chapter Five), tend to deal relatively effectively with a variety of occupational stressors, including change. Resilience also has both personal and environmental aspects that managers can influence. We have identified three actions that managers can take to increase employee resilience. Our recommendations come in part from analyzing data from the Towers Watson global database of high-performing companies. Figure 8.2 shows the areas in which high-performing companies improved in 2009 over the 2008 high-performance scores, in spite of the economic recession.

Managers can reduce the impact of adverse change by reinforcing the organization's commitment to honoring its deal with employees. As a stable basis for exchange, the deal must remain the solid, predictable core of the relationship between employee and organization. When change threatens the deal, people become distracted and distrustful. Note in Figure 8.2 that continuing to offer long-term opportunities to employees is a distinguishing factor of high-performing companies. In effect, these organizations have said to people, "We know times are tough, but we value you and what you bring to our organization. We intend to preserve that relationship."

In some cases, of course, organizations believe they have no choice but to alter the deal, usually to reduce cost in the face of economic pressure. Smart companies minimize the shock by avoiding layoffs where possible and aiming the biggest economic hits at the populations that can most afford them. In early 2009, for example, Hewlett-Packard (HP) CEO Mark Hurd announced that, in spite of continued economic pressure, the company would resist further staff reductions. Instead, HP would apply salary reductions across the employee population. But the pain was apportioned according to level in the organization. The pay of executive council members was trimmed by 15 percent. Other executives got 10 percent reductions. The base salaries of exempt employees went down by 5 percent, and nonexempt employees experienced cuts of 2.5 percent. Hurd took a 20 percent reduction. "We have to do something because the numbers just don't add up," he said. But he also told employees, "My goal is to keep the muscle of this organization intact." And he was prepared to take heat from Wall Street: "I'll be asked by investors, 'Where's the job action, where are you taking out this roughly 20,000 positions?' Well, I don't want to do that. When I look at HP, I don't see a structural problem of that magnitude."[261]

Widescale change like this affects not only how people perceive the integrity and effectiveness of executives, but also how they judge the fairness and trustworthiness of their immediate managers. People assess most forms of change, even those that have economy-wide causes and organization-wide effects, through the filter of their relationship with their direct supervisors. Like politics, all change is local. Employees will wonder to themselves whether and how their managers could have buffered the effects of change and whether they should have done something to make things better, or at least not as bad. The storehouse of trust shared by employee and manager will affect how an individual resolves these concerns. Consequently, every manager needs to ensure that any modifications to the employee deal scrupulously follow the criteria we define in the next chapter: fair process, fair outcome, fair individual treatment, and fair explanation. Note that in high-performing organizations, managers also make sure that employees have clearly defined performance goals. An environment of change is no time for ambiguity about what organizations expect employees to deliver or how they will be rewarded for their performance.

In many organizations, the first response to economic pressure and the perceived need to cut cost is a reduction in funding for training. Of the respondents to a Towers Perrin survey of cost cutting in 2008 and 2009, 45 percent said they had cut training programs or planned do to so within the next year and a half. Almost all of these cuts were expected to be applied organizationwide.[262] Witnessing this kind of action, employees must ask themselves, "Of all the assets this company could stop maintaining during times of economic pressure and change, why would they choose human capital, the one asset that will contribute most to our eventual recovery?" Good question—we often ask it ourselves.

Fortunately for line managers, the power of low-cost informal learning makes it a feasible strategy for continuing to build employee human capital, even, or perhaps especially, in times of cost cuts and organizational restructuring. In some cases, managers may be able to take advantage of reduced workloads to give people the development projects that didn't made the list when work flows were heavier. For the same reason, cross training may become more feasible. Firsthand experience with other jobs in the unit has several benefits: it expands employees' understanding of the group's strategic contribution; improves their ability to be effective team members; and increases the versatility that makes them valuable employees during lean times.

We've previously discussed how manager-directed learning can help employees build self-efficacy and mastery. But it can also do more. Research by a team from the Georgia Institute of Technology and the University of South Carolina–Upstate on how people respond to traumatic change suggested that individuals' beliefs about their abilities may buffer the effects of stressful job conditions. When people feel competent and confident in their ability to do their work well, uncertainty about the future decreases, fear of failure declines, and perceived loss of control diminishes. Job-related self-efficacy thus leads to change-specific self-efficacy. Self-efficacy in dealing with change, in turn, boosts resilience. Their analysis showed that high self-efficacy correlated with people's willingness to support change. After studying change experiences in a wide variety of organizations, the researchers concluded, "Individuals who feel more confident about their ability to handle change (i.e., have high change self-efficacy) should be less negatively affected by the demands placed on them by workplace changes and thus more willing or committed to support such changes than those with low change self-efficacy."[263] In high-performing companies, supervisors also take pains to make it clear to people that, even when everyone feels the urgency to adapt and perform well, it's OK to learn from things that go wrong. This sends two messages to employees: it's still important to grow human capital; and mistakes aren't fatal, even when the pressure's on.

Employees in high-performing organizations have confidence that their companies are beating the competition in product quality, innovation, and market flexibility. In other words, tough as times may be, these people believe that their organizations have maintained a focus on competitive leadership. Moreover, they express faith that executive leaders have a plan for preserving and extending that advantage in the future. What better way to build employee resilience than to reinforce their confidence in the company's future, and underscore their role in contributing to it? Belief in competitive superiority is a powerful tonic for the ills of economic trauma.

Managers contribute in part by ensuring effective cooperation among the unit's work groups. This not only brings the strategic focus down to the local level, but also reinforces the social contribution to individual resilience. Psychologists know that supportive relationships heighten resilience to stress.[264] Employees get a double benefit when they also perceive that the manager has focused team and individual efforts on strategically important goals aimed at achieving success in spite of marketplace challenges.

Resilience is like the tree in the Chinese proverb. The best time to build resilience, or plant a tree, was in the past. The second-best time is today. Everything a capable manager does every day contributes to employees' ability to function in any environment, including one full of turmoil and uncertainty. Farsighted organizations, the ones that know that hard changes are sometimes unavoidable, can support managers by providing employee training to increase resilience. Truly resilient employees emerge from change having grown and gained insight, so their future performance may improve because of the experience. Less-resilient people may simply revert back to their prior comfort zones—not a bad outcome of change, but not the best possible one. Employees who fall even further down the resilience scale may recover from change but never overcome the perception of loss and harm. Their motivation and engagement will continue to suffer. For some employees, the response to change may take dysfunctional or even pathological forms, leading to destructive behaviors.[265] Clearly, the stakes are high.

For an example of change with a strategic intent and presumed positive outcome, witness the evolution of Google since its incorporation in 1998. The company began life as a search engine provider, but its revenue model quickly evolved as the organization found a way to put advertising alongside search results. Later, Google introduced its Gmail service, which links advertising with the content of incoming messages. With this early form of artificial intelligence in its hip pocket, the company moved on to create or acquire Web features like Google Docs, Google Spreadsheets, Blogger, and the now ubiquitous YouTube. Nicholas Carr, former editor of the Harvard Business Review and author of The Big Switch, believes these Web applications signal a fundamental change in Google's business model. The next step involves continued moves into cloud computing, the data processing and management model that puts computing power into large centralized stations (in essence, computing utilities) that in turn sell this capacity to users. Says Carr, "Google is already a central computing utility. Up to now, it's supplied a limited number of computing services, mostly search. But what it wants to eventually become is the computer that people use instead of their PC or their company's data center." Think about that—Google as the world's computer, a far cry from its origins as a simple search provider.[269] The organization's business model no doubt will continue to evolve, especially if it succeeds in realizing its aspirations to expand the use of artificial intelligence and to deepen its ability to predict and act on the wishes and intentions of its users. Perhaps some day, a Google device (possibly a ninth-generation Nexus One phone) will whisper in your ear the answer to a question you merely thought.

What might this continued change mean for Google employees? Will they remain a bunch of technogeeks free to pursue their passions, or will the weight of corporate bureaucracy ultimately stifle their creativity? Google now employs some twenty thousand people. That's about the size that Microsoft and Cisco had reached when they began to struggle with the yin and yang of preserving an agile culture while toeing the line for a growing community of customers and investors. Will Google remain, like Xerox Parc or the old Bell Labs, a place for great minds to apply unfettered inventiveness? Will developers continue to have the freedom to spend 20 percent of their time working on pet projects, or will the next business model bring a more corporate (that is, restrictive) feel? Will the company's most imaginative employees be able to adapt to the next business model, or will they leave, disgruntled, to start their own businesses farther south on Highway 101? How must managers at Google (and other organizations with a strategic emphasis on innovation) energize change so that employees adapt and prosper? We have some ideas.

Pygmalion was a sculptor from Greek mythology. He fell in love with a female statue he had carved. The Pygmalion effect is the term psychologists now use to refer to the influence expectation has on performance. The greater the expectation placed upon people, the better they do, to a point. Remember the discussion of goal setting from Chapter Six, where we said that goals that are just about manageable have the greatest power to produce mastery and self-efficacy. In a work setting, managers set expectations for employee behavior, including creativity, by virtue of what they say (for example, by stating explicit performance expectations) and by how they behave. By providing resources, facilitating teamwork, and recognizing successful creative efforts, managers convey the expectation that employees should be creative. Properly calibrated, these actions not only build creative capability, but also increase employees' sense of self-efficacy.

In the words of Pamela Tierney and Steven Farmer, who studied the Pygmalion effect in an R&D setting, "Those employees for whom supervisors held higher creative expectations reported that their supervisors rewarded and recognized their creative efforts, provided more resources, encouraged the sharing of information, collaboration, and creative goal setting, and modeled creativity in their own work."[270] Tierney and Farmer point out the practical consequences for manager behavior: "Although other factors may come into play, our findings indicate that it is possible for supervisors to either stimulate or stifle employees' creative efforts by their beliefs and associated actions. This fact may become particularly relevant among members of the workforce who do not naturally view themselves as creative. Our finding that an employee's sense of mastery for creative tasks is linked to that employee's interpretations of the supervisor's actions highlights the importance of supervisors clearly communicating high expectations for employees' creative potential."[271]

The manager does not act alone. Her supportive actions must be bolstered by an organizational willingness to accept and accommodate new ideas. The sociopolitical context of organizations can at times militate against creative change, which entails, after all, a disruption to the status quo. Onne Janssen from the Netherlands looked at the relationship between manager support for innovative behavior and the perceived influence that individuals felt they had in the workplace—their belief that their actions would indeed achieve the desired effect. His research produced clear results: "Employees' sense of influence needs to be augmented by perceptions that their supervisors are likely to support their innovation.... Employees feel that their supervisors are the key actors who have the power to grant or deny them the support necessary for the further development, protection, and application of their ideas."[272]

The manager thus plays a dual role: fostering an environment that encourages and expects creative behavior, and providing the support necessary to ensure that such behavior is accepted and assimilated within the organization. We will return later in the chapter to the manager's role in providing performance support.

Team adaptation denotes the ability of group members to respond to emergent circumstances, using their resources either individually or collectively to meet expected or unexpected demands and to incorporate these into their repertoire of behaviors. A team headed by Shawn Burke of the University of Central Florida has advanced a model of team adaptation. The model posits that, "Adaptation lies at the heart of team effectiveness.... Team adaptation is manifested in the innovation of new or modification of existing structures, capacities, and/or behavioral or cognitive goal-directed actions."[273] Adaptation shares some features with team innovation, but also goes beyond it. Innovation may produce desirable ideas and novel products and services, but innovation as an activity may not change how the team functions. Team adaptation catalyzes that transformation.

Burke outlines four phases in the adaptive cycle within a team: situation assessment, plan formulation, plan execution, and team learning. Table 8.1 describes them and suggests ways in which managers can foster team adaptability.

Table 8.1. Developing Adaptable Teams

Phase | Features | Manager's Role |

|---|---|---|

Source: Adapted from Burke, C. S., and others, "Understanding Team Adaptation: A Conceptual Analysis and Model,"Journal of Applied Psychology, 2006, 91(6), 1189–1207. | ||

Situation assessment | One or more team members scanning the environment for cues likely to affect the team's mission. The new cues stimulate the creation of new mental models, leading to revised team situation awareness. | Help the team recognize the value of new cues that may disrupt habitual work routines. Suggest milestones, such as project halfway points or appraisal times, as a trigger to adapt or clarify and redefine purpose. Help team assimilate and share understanding of new schemata. |

Plan formulation | Agreeing on a course of action, creating and revising goals and priorities for the task, within the context of evolving environmental circumstances and constraints. | Encourage the group to review and possibly revise members' roles and accountabilities, as well as overall performance targets for the task. Ensure that the team feels safe to challenge and speak up and that information is adequately shared. As the plan is developed, offer counsel on which environmental factors are relevant to the task and which are not. |

Plan execution | Working toward the goal through individual or team actions, accompanied by mutual assistance by team members who monitor and give feedback, provide backup support, and communicate updates on progress. | Connect with external sources, provide judicious team and member coaching, ensure adequate resource availability, facilitate team problem solving, agree with team on how and when to review progress and revise procedures. |

Team learning and review | Developing team knowledge through ongoing reflection of activities and results, and incorporating those insights as a guide for future behavior. Using appropriate measurement and reward tools to ensure activities and results are evidence-based. | Encourage learning, which requires open discussion of mistakes and unexpected outcomes as well as successes, to foster an open climate of exchange within the team. Adaptation is continuous, so learning should be seen the same way, with sufficient time allocated to learning reviews. Ensure that measures are rigorously applied and analyzed and that team-based rewards link with performance. |

Burke and team extend the relevance of team adaptation to organizational performance as a whole: "Fostering team adaptation remains important to the effective functioning and thereby viability of organizations. In fact, the implications of the advanced model of team adaptation cross a wide spectrum of organizational functioning to extend to system design, information technology design, job design, assessment for selection, socialization efforts, individual development, team development, and more broadly, the facilitation of change at multiple levels."[274]

To be sure, the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune will at times so disrupt events that there is no choice but to decommission a team and start again with a new group. More often, we believe, teams can adapt their approaches, goals, and even membership to respond to redirection. The manager's success at promoting team-level adaptability will depend in part on how well she stimulates and supports flexibility without interfering in team functioning.

Whether imposed or chosen, major workplace change almost always brings stress. Stress, in turn, can undermine employees' rational and emotional engagement. Sustaining engagement through periods of stressful change is therefore a critical part of the manager's role. Engaged employees strongly connect with their organizations and consistently demonstrate willingness to go beyond minimum performance requirements. That willingness is never more important than when organizations are working their way through difficult transitions.

Why do some employees continue contributing to their companies in spite of turmoil while others become frustrated and burn out? Why do some keep on working productively as others struggle and fall short, distracted and enervated by the chaos around them? Why are some employees always at work and ready to contribute while others respond to strain by either staying home or showing up but underperforming? Individual attributes certainly play a role, but organizations and managers have a significant effect on how and how well employees cope with the consequences of change.

Our recent research on these questions has identified two factors required to sustain employee engagement through challenging periods:

An organizational climate that promotes employees' physical, psychological, and social health (we call this well-being)

A work environment that enables productivity (we've named this performance support)

Managers play a critical role in ensuring that the organization delivers in both areas.

Within the organizational context, well-being comprises three related aspects of individual wellness:

Physical Health. Overall bodily wellness, encompassing general health as well as specific medical conditions. From the company's perspective, physical health manifests itself in factors like low absenteeism, low presenteeism,[275] strong productivity, and high levels of stamina and energy on the job.

Psychological Health. Optimism, confidence, and perceptions of satisfaction and accomplishment, balancing factors such as stress, anxiety, and feelings of frustration. Psychologically healthy people typically express happiness, positive attitude, and enthusiasm for work.

Social Health. Quality of relationships with supervisor and colleagues. People who experience high social health say that they get along well with fellow employees, feel treated with respect, and are able to balance their work and personal lives.

Well-being helps sustain engagement by providing employees a shield against the stresses associated with workplace change.

The work environment created by first-line supervisors and managers has a direct effect on employee well-being. A growing body of studies shows, for example, that supervisor and manager behavior affects individuals' blood pressure and risk of heart disease. To test this relationship, researchers from the Karolinska Institute and Stockholm University in Sweden tracked the cardiovascular health of male employees aged nineteen to seventy, over nearly a decade. Those who deemed their managers to be the least competent had a 25 percent higher risk of a serious heart problem. In a British study published in 2005, the researchers found that men who described their supervisors as fair and just had reduced stress and a 30 percent lower risk of coronary heart disease than those who said they were treated unfairly at work.[276]

A related Swedish study produced a specific list of manager behaviors that contribute to employee well-being in a dramatic way—by reducing ischemic heart disease.[277] The analysis was intended to assess the factors underlying a recent finding that there is an average excess cardiovascular risk of 50 percent in employees who are exposed to an adverse social and psychological work environment. The team of Swedish doctors and academics set about to determine precisely what kind of manager performance elements contribute most to employees' avoidance of cardiovascular problems. They identified four manager behaviors strongly associated with lower incidence of ischemic heart disease:

Providing the information people need to do their work

Effectively pushing through and carrying out changes

Explaining goals and subgoals for work so that people understand what they mean for their particular parts of the task

Ensuring that employees have sufficient power in relation to their responsibilities[278]

These themes aren't surprising—they reflect key elements of the task execution and employee development components of our manager performance model. What may be more surprising is the effect these factors produce not only on the psychological and social aspects of employee well-being, but also on the physical aspects. These three forms of well-being influence each other, of course, and so a manager's effect on any one will likely manifest itself in the others as well. As the researchers observed, "Psychosocial stress has been shown to increase the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. One could speculate that a present and active manager, providing structure, information and support, counteracts destructive processes in work groups, thereby promoting regenerative rather than stress-related physiological processes in employees."[279]

Employee well-being is important for reasons that extend beyond sustaining engagement and providing regenerative power in the face of organizational change. The well-being of the workforce also has major implications for organizations' health care costs. By one calculation, American employers spend $13,000 annually per employee in total direct and indirect health-related costs.[280] Moreover, for every dollar expended on medical services and pharmaceuticals, companies spend another $2.30 on health-related productivity costs—the expenses associated with absenteeism and presenteeism.

Depression is the single most expensive health condition, carrying an annual total cost of more than $350 per full-time employee. Of that total, more than three-quarters comes from lost productivity because employees don't come to work or are relatively unproductive when they do show up.[281] In this context, consider how managers who perform in ways described by the Swedish research team—being present and active, providing information and support, reducing workplace stress—can yield significant health care cost reductions for their organizations. By reducing the care requirements associated with depression and anxiety alone, managers can make a major financial contribution to their companies. Add to that the competitive advantages that accrue to companies whose employees not only require significantly lower health care support, but also continue to innovate and produce efficiently in spite of traumatic change that threatens to cripple the competition. There lies a multifaceted marketplace edge ready for the taking, an advantage to which managers can make a material contribution.

The most forward-thinking organizations have introduced well-being programs that incorporate manager involvement into broader initiatives aimed at creating a healthy work environment. This is the approach taken by WorkSafe Victoria (WSV), an Australian state authority with responsibility for ensuring adherence to health and safety laws and providing care and insurance protection for workers and employers in Victoria. According to Dale Nissen, the WSV well-being program manager: "We were already supporting some health initiatives but decided to pull these together into a well-being program in 2007, with strong support from the top and mutual commitment with employees." The program, called "Feeling Good@Work," includes an online site where employees can learn about available activities as well as complete self-assessments and review and update their own records. Says Nissen, "We created some big events to get the momentum going, such as our Global Corporate Challenge, a team-based walking challenge which involved walking round the globe over the Internet. After 12 months of exercise programs, people now are used to doing exercise at work, using the facilities we provide."[282]

The WSV program incorporates involvement from managers at all levels of the organization. Says Geraldine Coy, WSV's head of HR, "We've worked on a leadership development program to ensure that we are bringing the various threads of well-being, career, learning, and development into a set of congruent messages for our people. Every year we run a forum for our people managers. The last two have put emphasis on the well-being program to ensure managers are up to date with our progress and given the opportunity to act as role models themselves."[283]

Managers provide unit-specific support for performance by making sure employees have the wherewithal to execute their jobs effectively. Providing support means ensuring that workplace strain isn't exacerbated by inadequate tools, insufficient resources, taxing work, or organizational barriers. Managers get high scores when employees perceive that:

Physical work conditions are comfortable and conducive to high productivity

All the resources required to do their jobs (physical, financial, informational) are readily available

The necessary equipment and tools have been provided

Safety on the job is never compromised, even at the expense of output

Unit staffing is sufficient to ensure that the workload is manageable and fairly spread

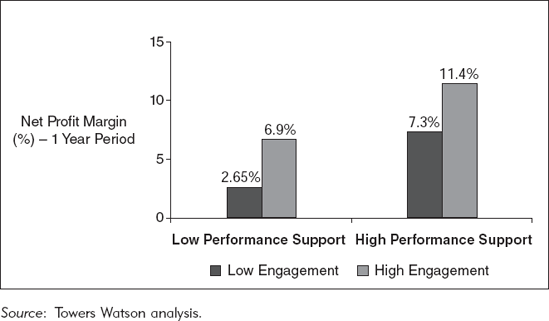

This list may seem familiar—we included these kinds of factors in our definition of job resources in Chapter Five. Much as they help make challenging work fulfilling, they also help sustain employee engagement. When managers deliver these requirements, as Figure 8.3 shows, they also boost the effect of employee engagement on company profit.

High performance support adds to the profit margins of both low-engagement and high-engagement organizations. In both engagement categories, performance support contributes about five percentage points to profit results. Among the worldwide respondents to our 2010 global workforce study, 74 percent of those who gave their managers high ratings for effectiveness also agreed that their managers succeed at removing obstacles to doing their jobs well. In contrast, only 12 percent of those who scored their managers as ineffective overall gave a positive rating for clearing obstacles.

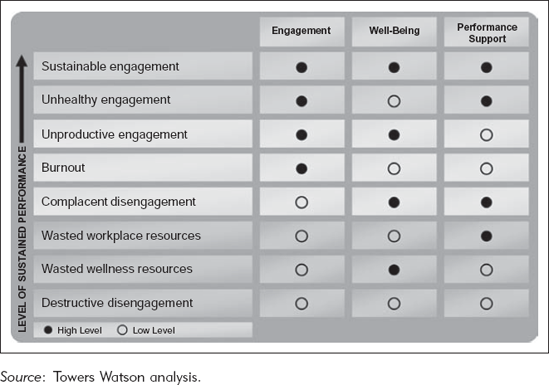

Together, well-being and performance support have a complementary effect on the sustainability of engagement. Neither factor by itself is sufficient, but together they produce a powerful result for individuals and organizations. Exhibit 8.2 shows the results of various combinations of high and low engagement, well-being and local performance support.

Remember, these factors act not as drivers of engagement, but rather as sustaining elements. We see many companies, including some going through rapid transitions, that record high engagement scores, particularly if their change efforts involve sexy new business strategies or appealing innovation efforts. However, these companies are often too distracted by their redirection or restructuring activities to worry about employee well-being or the details of unit-level support. Consequently, they find that their engagement scores drop and their ability to preserve the momentum of change diminishes. Neither well-being nor performance support alone can preserve high engagement. But together, they can help an organization emerge from the trauma of change with an employee population still committed to the organization and willing to work hard on its behalf.

Creating change in organizations is often seen as a job for the CEO and his team of senior executives. Certainly, in large-scale change programs, their involvement is essential. Alternatively, organizations that see senior leaders as the primary instigators and drivers of change may pay insufficient attention to how effective change actually happens.

In the context of change, much of what we expect of managers falls into the leadership category. The requirements we've laid out, with a focus on creating the circumstances in which people willingly—or at least cooperatively—move toward the future, belong squarely under the definition of strong leadership. At the same time, change at the individual and unit levels also calls for effective management. Procuring the resources for local performance support is an example. Failures of leadership can leave employees with insufficient direction, whereas failures of management may mean employees have to do too much work with too little support. The former brings chaos; the latter brings burnout.

Whether leading or managing, supervisors must redouble their attention to the people-focused part of their jobs. We might even suggest that successful change requires managers to move a bit toward the center of the stage, to reduce the distance we have recommended they otherwise maintain from the work of their autonomously performing employees. Adaptability, resilience, and well-being result from the manager's specific attention to individual employees. This is no time for a manager to be closeted in his office revising budgets or writing reports. Instead, managers need to be with their employees, not interfering with their work, but ensuring that everything they do contributes to individuals' ability to survive and thrive in spite of workplace disruption.

Regardless of the sources of change or the kind of employee response required, the manager nevertheless carries a heavy burden. The attention required of managers touches all parts of the manager performance model described in Chapter Three. In seeing to the execution of tasks, managers must know that the uncertainty brought by change means the focus on strategically critical work is more important than ever. People need to be confident that, in an unpredictable world, their work helps to create the organization's future. Involvement, autonomy, self-efficacy, and mastery become more important in times of change than in stable periods. They build employees' confidence in their ability to maintain their valued and valuable positions with the enterprise. For the same reason, continuing to provide learning opportunities not only enhances the shared human capital asset but also gives employees hope for a future where their skills will be necessary for organization success. Preserving the deal between individual and enterprise reinforces the organization's determination to continue rewarding the fruitful investment of human capital. Recognizing those who perform well sends the message that, especially when the ground is shifting, high performers stand out; their contributions deserve special acknowledgment.

Organizations that navigate change successfully have managers who make the case for change, who explain why things need to be different, and who never fail to provide full, honest, and timely information. These actions lie at the core of authenticity. They reaffirm that employees can trust their managers, even if the news isn't always good or the immediate future not entirely rosy. At the same time, managers need to encourage realistic hope in employees, give them reason to be optimistic about the future, and increase their confidence that the organization knows how to survive and will ultimately thrive.

To help employees handle the stresses and make the most of the opportunities associated with major change, effective managers will:

Carefully consider the magnitude and sources of change and help each person respond with the appropriate levels of adaptability and resilience

Do everything in their power to preserve the deal between employees and the organization, knowing that trust for both company leaders and unit managers is at stake

Not just keep people focused on their work, but also help them raise their sights and draw energy from the opportunity to leapfrog weakened competitors

Convey high expectations for innovation, and back these up with encouragement, support, and resources

Help teams navigate change, but do so with respect for team competence and therefore a suitably light touch

Not just help employees survive the emotional toll exacted by uncertainty and tension, but also invest in preserving their well-being and in keeping them healthy physically, psychologically, and socially

Much of what we've recommended in this chapter will sound familiar. An environment of change doesn't modify the requirements for strong manager performance. Rather, it intensifies the importance and heightens the need.