CHAPTER OUTLINE

Manager Role Structure and Performance Model—A Summary

What Makes a Great Manager?

Requisite Variety

Cognitive Fluidity

Ability to Catalyze Action

Ability to Navigate the Organization

Social Intelligence

Can a Good Manager Manage Anything?

Make Versus Buy

Notes for Those Who Want Managers to Succeed

What Executives Can Do

What Human Resources Can Do

In the final act of Shakespeare's The Tempest, Prospero, magician and exiled Duke of Milan, presents a group of shipwrecked prisoners to his daughter, Miranda, for inspection. The only people she knows are her bitter old father and his deformed slave, Caliban. She is struck by the sight of the men: "O, wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world that has such people in't!" By "brave" Miranda doesn't mean courageous, but rather stunning and splendid. Her father knows better, having experienced the world beyond their small island. He responds simply, "'Tis new to thee."

As we reflect on the manager job we've constructed here, we confess that it will take a splendid person to carry it off. But we're optimistic that such men and women are plentiful in many companies. Organizations merely need a clear view of the human capital required for a manager to succeed and a practical approach to identifying, obtaining, and developing the necessary knowledge, skills, talents, and behaviors. There is no dearth of manager and leader competency models. We don't propose to create yet another one. Instead, we want to lift our sights and provide a few higher-level thoughts about the attributes that matter most for the manager role we've defined.

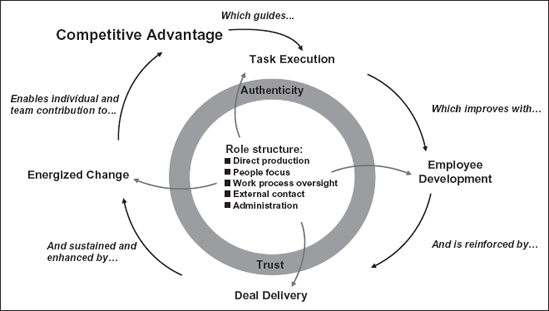

Before we launch into our discussion of high-level attributes, let's first review what we think managers need to be able do. Figure 10.1 depicts the elements of the manager role architecture and performance model we've defined. It takes the components illustrated in Exhibit 3.1 and shows the connections among them.

At the center sit the five basic job segments and time allocation opportunities available to an individual manager. Those structural components are expressed through the action elements of the performance model: executing tasks, developing employees, delivering the deal, and energizing change. As the graphic shows, strategic requirements inform job structure and task definition. Development of human capital gives individuals and teams the capability to carry out those strategically critical tasks; delivery of an engaging, intrinsically valuable deal reinforces task-execution success. The world doesn't stand still, however, so good managers must maintain momentum by responding to and inspiring change. When managers perform well in all these elements, demonstrating authenticity and building trust in the process, engaged employees accomplish their goals. When that happens, organizations win in the marketplace and prosper as a result.

Executing well in this system requires managers to possess a generalized set of cognitive, emotional, and action-oriented characteristics. They must have the intellect to plan work and monitor results, ensuring a consistent focus on what matters to business strategy. They must have sufficient social and emotional insight to structure fulfilling jobs, ensure meaningful learning, understand individual reward needs, and sustain employee engagement. And they must know how to identify and exploit organizational resources to keep their teams executing and moving forward.

It's a daunting list of requirements, but we think not an impossible one, provided managers bring the right human capital to the job. We define the right human capital as a set of broadly scoped elements, each with plenty of room to comprise more precisely specified competencies. We're suggesting the main ingredients for manager success. Competency experts can translate these into a recipe.

We've intentionally left some contributors to manager performance off the list. For one thing, we haven't touched on the technical side of the job. We know from thinking about the S-Zone (Exhibit 4.1) that technical knowledge plays a role in managerial performance. However, we're leaving the definition of "technical competence" to individual organizations and functions. We simply reiterate that outstanding manager performance relies more on other elements than on technical prowess. We also haven't touched on the abilities and attitudes required of everyone in the organization, factors like business acumen, or comfort with diversity. Instead, we've concentrated on the classes of factors specifically required for supervisors and managers to be successful within the performance model and role structure we've defined.

We have constructed the definitions so that they apply to any strategy category and across any organizational function, albeit with varying interpretations and applications. For instance, navigating the organization will take on a specific meaning for a store manager in a retail operation with a widespread network of outlets but a highly centralized corporate training function. It will mean something different for a high-tech engineering manager who works in a small regional office but has a development team scattered across three continents and five time zones. Catalyzing action will take on different forms for an Internet service provider with an evolving business model, a video rental company facing cost pressure from a Web competitor, and a bank trying to recover from a global financial shock. On the one hand, social intelligence will retain its fundamental meaning in any situation requiring interpersonal interaction. On the other hand, we would expect it to feel different for R&D, marketing, and call center managers.

You will also notice that the performance elements do not fall neatly into leadership and management categories. We have suggested that managers will rarely stop in the middle of an activity and ask, "Am I leading or managing at this moment?" Instead, they should be asking, "What can I do at this moment to help the people in our unit perform best at executing this process and producing the results for which we are responsible?" As they answer this question, managers will think about systems, assets, and processes (the substance of managing) and about how people can exercise self-determination in working with these to execute tasks (the essence of leadership). When we speak of navigating the organization, for instance, we intend it to apply to managing (for instance, identifying and acquiring important assets, such as budget funding for a project or information to guide a decision). But we also mean it to encompass leadership (keeping people focused on strategic goals as they move through an organizational matrix, for example). In a similar way, cognitive fluidity enables a manager to see how two systems might be combined to improve efficiency (a management challenge) or to envision how to foster cooperation among three differently talented technicians to develop a novel solution (a leadership situation).

Here then are the summary attributes that we believe contribute most directly to a manager's success at playing the roles we've outlined, across strategies, companies, and functions.

This concept comes from systems theory, specifically the cybernetics discipline. It means simply that a flexible system encompassing many options performs better in an uncertain environment than does a system with fewer options. That is, only variety can respond to variety. For managers, this means having the insight to recognize, and the adaptability to respond to, a range of employee attitudes and behavioral styles. The goal is efficient connection and personal rapport. We don't propose that managers become behavioral chameleons; that would violate the precepts of authenticity. We do suggest, however, that a manager must be able to call on a range of behavioral modes to respond to an equally wide array of employee styles. This adjustability enables a manager to have the kinds of conversations required to craft person-specific jobs, create individualized development plans, and deliver customized reward deals. The required stylistic flexibility has a foundation of empathy. Requisite variety subsumes such traditional manager competencies as adaptability and effective communication.

Cognitive fluidity goes beyond simple brain power. It denotes the ability to make intellectual connections across topics and domains. We've borrowed the concept from evolutionary psychologists. They use it to describe the growing capacity among early modern humans to connect intellectual domains—for instance, information about their environment, the tool-making materials at hand, and social relationships—to create and pass on new knowledge. In neurobiological terms, cognitive fluidity calls on the brain's executive function to combine observation, forethought, analysis, and problem solving.

Cognitive fluidity as we mean it requires balance. This implies, for instance:

An ability to focus on near-term operational requirements without losing sight of the future (that is, being adept at using both a microscope and a telescope)

A knack for seeing the details of an issue without missing the big picture (having both a sharp pencil and a dull pencil)

A finely tuned judgment about when to assist and when to maintain distance (displaying conscientiousness balanced with a let-it-be confidence)

A vision for how the future should both resemble and differ from the past (for example, by employing the counterfactual exercises we outlined)

More than just balance, however, cognitive fluidity calls for connectivity and mental agility. A manager strong in this attribute will prove effective, for example, at determining how a redirection of business strategy will affect unit-level work planning and operational requirements; discerning the meaning for organizational structure; and identifying the ripple effects on individual employees and their deals with the organization. The required intellectual plasticity and balanced processing contribute to stimulating and coping with change and underlie managerial authenticity. Cognitive fluidity incorporates such classic manager competencies as problem solving; analyzing and interpreting; comfort with ambiguity; and capacity to incorporate multiple points of view.

The essential paradox of our concept of the manager's job is that managers can perform better from offstage. This means acting as a catalyst, precipitating results without participating as a functional element in the processes used by individuals and teams. The manager-as-catalyst attribute encompasses classic competencies like results focus, bias for action, and goal-orientation. But we mean something more. To perform as a catalyst, a manager must combine relentless attention to what matters with a highly developed ability to get out of the way. This means paying close attention to results, taking subtle corrective actions when necessary, but rarely interfering directly in work processes. Catalytic management calls for a combination of conscientiousness and what psychologists refer to as emotional stability—equanimity, calm, and an ability to trust others and give up direct control. A successful manager-catalyst will be comfortable designing jobs that offer abundant opportunities for employee mastery and autonomy; creating employee deals that contain plenty of potential for intrinsic fulfillment; and chartering self-managing teams that deliver high performance unimpeded by managerial interference.

Compared with the other categories, this one may seem mundane and prosaic. But don't be fooled. The ability to find and use an organization's tools and resources contributes as much to manager performance as does any other high-level attribute. This is the ultimate example of firm-specific, how-we-do-things-around-here knowledge. It requires cognitive fluidity, which enables the manager to see readily how to connect disparate resources (such as diverse learning programs) into a unified result (a practical development process for a single employee). Social intelligence also comes into play as the manager forms bonds with allies and builds networks of sources. Those bonds and networks may well extend beyond the boundaries of the company as the manager forages widely for useful ideas and assets. Moreover, by introducing employees to the web of contacts created, the manager multiplies the value of the relationships. Successful organization navigators display such classic competencies as business acumen and boundary spanning.

You may wonder why emotional intelligence doesn't appear on our list but social intelligence does. In Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman divided emotional intelligence into five major components: knowing one's own emotions, managing emotions, self-motivation, recognizing emotions in others, and handling relationships.[317] The characteristic we call social intelligence did not emerge discretely, but rather was embedded in these dimensions. In his later book called Social Intelligence, Goleman admits to a revelation: "As I've come to see, simply lumping social intelligence within the emotional sort stunts fresh thinking about the human aptitude for relationship, ignoring what transpires as we interact. This myopia leaves the 'social' part out of intelligence."[318]

We view emotional intelligence as critical for any person working in the society of others, whether playing a leadership or team member role. It is important for success and fulfillment in any interpersonal interaction. Hence, we consider it applicable to every member of an enterprise. But because the manager's role as we've defined it is essentially social—working with people being the definitive aspect of the job—we've identified social intelligence as the most relevant application of the connective elements in Goleman's conception of emotional intelligence.

Goleman includes two components in his definition of social intelligence: awareness (gathering information on others and understanding how the social world functions) and facility (effective interactions using the information gathered).[319] These attributes provide the interpersonal insight and the influence skill needed to navigate within and outside organizational boundaries. Social intelligence encompasses the authenticity that guides managers to honest understanding of their own and others' strengths and weaknesses. It's a key to working with teams from the right distance and creating the networks that provide learning contacts. Humility is essential; a sense of humor doesn't hurt. A socially intelligent manager typically displays extroversion (positive energy and emotions; interest in exploring; tendency to seek stimulation and to enjoy the company of others), and agreeableness (compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, a spirit of cooperation, and motivation to achieve interpersonal intimacy). Both are personality traits commonly associated with transformational, high-authenticity leaders. Empathy provides a foundation for social intelligence by enabling a manager to gather, reflect on, and interpret the interpersonal information required to build bonds with individuals and groups. Traditional competencies like interpersonal skills, persuasiveness, and team-building come under the umbrella of social intelligence.

By defining this set of fundamental elements, we've tried to create a general definition of what characterizes a strong manager. It follows that, even across organizations with different strategies and across various functions, high-performing managers should be more similar than dissimilar. But let's consider several variations of the question that heads this section. Sometimes, the question takes this form: "Should we move our R&D manager over to product development?" This idea assumes that the R&D manager has amply demonstrated the knowledge, skills, and talents that we've defined here (and the subordinate competencies they embrace). Otherwise, why would he be a manager in the first place, let alone a candidate for transfer and possible promotion? If an individual demonstrates these high-level attributes, then the question of transfer feasibility boils down to an assessment of technical skills and knowledge. How important are these to the manager's credibility and ability to guide, coach, and develop employees? Does the candidate possess them now? If not, how feasible would it be to develop them (see the make-buy discussion in the next section)? Answers to these questions govern the practicality and advisability of cross-unit transfers.

Another variation on the good-manager theme has to do with hiring from outside the organization: "Can we bring in a new sales manager from our main competitor?" In Chapter Three, we made the case that firm-specific human capital is important to achieving strategic advantage and is often a barrier to successful external hiring. It is risky to bring people from the outside into positions where success depends strongly on company-specific knowledge or idiosyncratic applications of technical skills. We would caution that, in many cases, adding a firm-specific inflection to already developed knowledge and skills will prove either too time-consuming for the individual or too expensive for the organization, or both.

We often encounter this question: "Should we move our best technical performer into a manager role?" As we've tried to make clear, we think promotion chiefly for technical reasons is a big mistake. An exception would be made for a candidate who occupies the far upper right-hand corner of the S-Zone (Exhibit 4.1). This person has strong performance ability along both the managerial and technical dimensions. When you have a candidate with these qualifications, close the deal. Conversely, promoting someone from the lower right-hand corner of the grid is a formula for disappointment across the board. Doing this takes a top producer off line (hurting output); creates at best a mediocre manager (decreasing employee engagement and well-being and diminishing unit performance); and puts an individual into an untenable position (talk about a stressful job!).

Perhaps the most fundamental question facing companies seeking to ensure a population of great managers is this: is it better to develop the performance requirements or to obtain them through hiring and selection? Psychologists debate the degree to which personality elements are subject to change, either from affirmative efforts like training or simply from the effects of maturity as people age. On the one hand, exhaustive analysis of personality traits and their manifestations, often through twin studies, suggests that the five foundational personality factors—extroversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience—are between 40 and 50 percent heritable.[320] Personality features, like other characteristics of homo sapiens, evolved for a reason: they helped our early ancestors survive long enough to reproduce and be attractive enough to the opposite sex to find a mate. Those traits therefore have a deeply ingrained quality that makes individual change difficult. Psychologist Martin Seligman summarizes the situation like this: "Evolution, acting through our genes and our nervous system, has made it simple for us to change in certain ways and almost impossible for us to change in others."[321]

Dr. R. Grant Steen believes that we must separate the part of the personality that remains stable over time from the part that changes under the influence of life events, including learning experiences. The first element he calls temperament; he labels the second character. He describes the interplay between our genetic programming and our experience this way: "In a crude sense, we cannot do what we are not programmed to do. But equally true, we cannot do what we are programmed to do if the environment does not facilitate so doing. Environment can amplify or blunt the effect of genes, but environment cannot replace or displace genes. After the connections between neurons are made during development, it is up to the organism to use those connections." Steen also points to the work of Donald O. Hebb of McGill University, who taught that "heredity determines the range through which environment can modify the individual."[322]

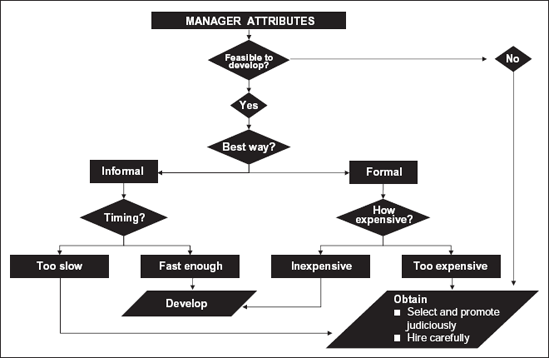

Which takes us back to our basic question: given what can be changed and what can't, what's the best way for an organization to create a cadre of managers who possess the attributes we've defined? We suggest that the process depicted in Figure 10.2 provides a way to approach the issue.

The thinking begins with the question of feasibility. The behavioral traits that are most deeply embedded in the personality will prove most difficult to train. We would place elements like requisite variety in this category. Developing this in people who demonstrate little flexibility in responding to others' emotional states will prove a sizable challenge, perhaps not impossible with enough time and attention, but difficult nevertheless. In contrast, aspects of catalyzing action (a skill) and navigating the organization (a bundle of knowledge) will more likely respond to training.

Once feasibility has been sorted out, the next question relates to cost and timing. For simplification, we have assumed that formal development programs can be brought on line fairly quickly. An organization can often purchase or design and deliver a training program in relatively short order. We have also assumed that informal learning takes longer to have an effect. On-the-job training and mobility strategies unfold at a pace more measured, less predictable, and more particular to each individual. Conversely, formal training brings a higher price tag than more informal, organic forms of learning.

In any given case, of course, cost and timing advantages and disadvantages may not align so neatly with the formal and informal learning categories. But the point remains that analyzing these factors can help an organization determine whether and how to invest in development approaches. These come down to strategic choices—how much time has the marketplace given us to put great managers in place in a particularly critical function? How much can we afford to spend on building manager capability, given the cost pressures we're feeling? Often, we believe, organizations will conclude that the most sensible approach to populating the company with great managers will chiefly depend on careful assessment and selection among internal candidates. Occasionally, with all the caveats we've suggested, outside hiring might prove feasible. However, this will require the organization to show patience as an individual's preexisting schemas and scripts are rewritten for the new company.

In all this we must remember the thoughts of Stanford's Carol Dweck. She would remind us that executives and learning and development strategists owe it to managers and manager candidates to keep an open mind about the potential to learn. Even Prof. Dweck wouldn't argue that all human traits are infinitely plastic and therefore subject to remolding. She would say, however, that no one, including individuals themselves, can fully understand a person's potential to grow. To those assessing and developing managerial candidates, she would say that they should maintain an optimistic realism about the ability of people to change and grow. They owe it to the organization and to employees to have faith that human capital can evolve and increase. She would admonish them to back up that faith with a thoughtful assessment of how best to create and build an organization's managers.

Organizations shouldn't expect managers to execute all the elements of the performance model by themselves. Like all employees, they need tangible and intangible resources to meet the demands of their jobs. The executive group and the Human Resources function both play important roles in helping managers effectively perform their task-execution, people-development, deal-delivery, and change-energizing roles. We have some specific thoughts about the support that executives and HR need to provide.

Your job is to lead your organization to the promised land of marketplace advantage. This means looking behind every tree and under every rock for a competitive edge that your company can seize and hold on to. As we've suggested throughout this narrative, we believe your supervisors and managers represent a source of such advantage, latent in most organizations but nevertheless full of potential. Executive leaders can do some specific things to realize this potential:

Challenge your point of view about your organization's supervisors and managers. Talk about them differently in executive planning sessions. Speak about them frequently when you appear before employees to cite the strengths of the organization. Elevate their profile in the company, making the position a sought-after prize for the successful and truly qualified. Think constantly about how you can take advantage of their contributions and their influence over employee behaviors.

Make sure your organization's managers have full access to all the detailed strategy information they need to ensure that their units can make the maximum contribution. They can't create a line of sight between jobs and business strategy unless they have this knowledge.

Do all the things for your managers that you want them to do for their employees. Let them craft their jobs; have autonomy in executing their responsibilities; receive recognition, individually and collectively, privately and publicly, for their success; and increase their self-efficacy and mastery.

Provide them the same kinds of human capital development opportunities they give their employees, with emphasis on challenging assignments that accelerate their growth. Coach them, guide them, give them access to your network, let them learn from their mistakes—and yours.

Demonstrate frequently that you care specifically about manager engagement and well-being. They can't enhance employee engagement or attend to people's physical, psychological, and social health if their ability to sustain energy is compromised. Measure and monitor managers' engagement and well-being levels and take action if either deteriorates.

When difficult change becomes necessary, make the case for change clear to your managers and then let them decide how to take action in their individual units. Adhere to a model of dispersed responsibility for organizational change. Let your managers meet the company's needs by crafting a local response for which you, as executives, can hold them responsible. Avoid hamstringing them by forcing sweeping change that may be insensitive to the circumstances in any single unit and therefore may cripple a manager's ability to deliver the results you need.

Make your organization the best, and best-known, place to become a high-performing manager, the company that provides the highest rewards, both intrinsic and financial, that such status carries. Think about the advantages you'll gain:

Competitive superiority (because your managers keep everyone relentlessly focused on doing work that achieves the organization's vision for success)

Recruiting superiority (because who wouldn't want to come to your company, given its reputation as the place to work with, and become, a great manager)

Human capital superiority (because your people have better opportunities than your competitors to learn and grow and improve their performance)

Workplace superiority (because your people are not only more engaged and more capable than your competitors' employees, but also better able to sustain high productivity and respond to change)

Is there such a word as quadfecta? If not, there should be—because these four points make one.

HR's first job is advocacy, urging executives to accept that the performance model laid out here produces better economic results for the organization than other manager job concepts. HR professionals must do the economic analysis to prove where on the spectrum between Widget Wizard and People Powermeister an individual manager's job should lie. They must become evangelists for the role structure that makes it possible for managers to fulfill the potential we've identified.

Here are some of the specific requirements:

Make sure your managers understand the broad human capital strategy of the firm and how it links with the enterprise business strategy.

Don't compromise on the required attributes when filling open supervisor and manager positions. Search diligently until you find candidates in the S-Zone. Examine your compensation systems, titling conventions, and cultural norms for prestige. Don't allow these factors to drive your company to promote people into positions where they can do more harm than good to the organization, their employees, and themselves. Waiting for the right candidate, even if the wait is uncomfortably long, is better than putting the wrong person in any supervisor or manager job. Whatever benefit comes from filling a position quickly soon disappears if employee engagement, development, performance, and well-being are sacrificed. Design and implement a sound process for identifying and nurturing people in, or on the edges of, the S-Zone.

Make it a top priority to do something about the low-performing managers in the organization. Some should go back to being individual contributors—and they would probably be happier if they could. Others simply may not belong in the company. Don't prolong their agony and yours by keeping them in positions that drain their energy and hinder organizational success.

Consider letting individual contributors have a trial run in their first supervisor position, perhaps overseeing a specific initiative or a modest project. Make it a brief, no-harm-no-foul experience, and then decide whether they can best contribute as managers or as direct output producers (but not both). Let them choose that path with impunity.

Define manager performance metrics that reflect the full contribution of the role. Don't overemphasize the manager's direct production. Instead, focus chiefly on the unit's production and financial performance, but also monitor the growth of employees' human capital, the state of their engagement, and their levels of perceived well-being. Monitor the links between manager behavior and health care cost. Ensure that metrics are few in number, clearly linked with enterprise strategy, insightful, and suitable for guiding action.

Structure managers' reward portfolios—the deal they have with the organization—so that they align with these ways of measuring. Don't tilt the pay system toward individual output.

Prepare managers to play their part in delivering the deal. Don't make them solve mysteries about the components or intention of the organization's reward systems. Give them latitude to apply those systems with judgment and individual sensitivity. Executing this responsibility requires that, at a minimum, HR will:

Ensure that managers understand both the high-level philosophy and the details of individual reward system components, financial and nonfinancial

Provide information to managers on the competitive reward environment and the relative market positioning of the organization's reward programs

Educate managers in how to communicate the intent and the outcomes of reward system events, such as incentive payments

Train managers rigorously in using the company's performance management system, including both the mechanics of the process and the relational elements of employee coaching and feedback

Make sure your managers have full information about the organization's learning and development opportunities. In particular, help them map the available cross-organization moves, so that they can guide employees in their use and integrate them suitably with other learning strategies. Also ensure that managers' efforts to help employees develop their human capital align with goal setting, performance evaluation, and rewards. HR must own the fully articulated system that managers apply.

Don't give in to the temptation to shift HR duties to managers without a careful assessment of the workload and time allocation implications. Our performance model places high enough demands on them. Don't make managers' jobs harder by giving them a heavy load of HR administration tasks.

Help managers themselves develop a growth-supporting perspective. To do this, a workshop conducted by the SMU–University of Toronto team took a group of managers through an exercise with these five elements:

Scientific testimony, delivered via an article and a videotape, about how the brain, and hence intelligence, can grow strong much as a muscle does.

Exercises in which participants generated responses to the question, "As a manager, what are at least three reasons why it is important to realize that people can develop their abilities? Include implications for both yourself and for the employees you (will) manage."

Reflections on their own experience, with the managers considering areas where they had improved and thinking about how they were able to make those changes.

Writing an e-mail to a struggling hypothetical protégé about how abilities can be developed; participants were encouraged to include anecdotes about how they had personally dealt with development challenges.

Having participants identify three instances when they had observed someone learn to do something they had believed the person could never do, explain why they think the achievement had occurred, and reflect on the implications.

This format focused chiefl y on self-persuasion. At the end of the training, managers who had held a fixed-ability philosophy tended to migrate to a more fl exible point of view.[326]

Remember that employee well-being is a whole-system concept that requires close connection between managers and HR. Make it a campaign to work with managers to understand and improve well-being. The potential health care cost savings are dramatic.

Never put managers in a position where they must compromise the trust they have built with employees. This means always ensuring that they have full information about the organization and its strategy, challenges, and position in the marketplace. It also means giving them freedom to respond to organizational change in ways that preserve their integrity and reinforce their authenticity.

Your relationship with managers should have many facets—ally, trusted adviser, coach—with each party playing these roles for the other as the situation requires. When the relationship works best, manager and HR will act as partners—investment partners, business partners, sparring partners. After all, you have a common goal: to make the enterprise competitively successful through the contributed strengths of the employees who work there. You should need no more powerful bond than that goal, and no greater reason to do all you can to ensure that your manager population becomes a source of sustainable success.