2.1 INTRODUCTION

In the previous chapter we stressed how the recent financial crisis was exacerbated by an increased funding liquidity risk that contaminated market liquidity for many structured products. In order to understand how liquidity risk can impact financial stability, we have to look closer at the various types of liquidity and deeply analyse the concept of liquidity itself, still vague and elusive in the literature.

The concept of risk is related to the probability distribution of the underlying random variable, with economic agents having well-defined preferences over the realizations of the random variable of interest. As economic agents would have a preference over liquidity, the probability of not being liquid would suggest the existence of liquidity risk.

To begin with, we need a coherent framework that properly defines and differentiates the financial liquidity types, and describes the transmission channels and spillover directions among them. For each liquidity type the respective liquidity risk will be defined.

We will refer to the work of Nikolaou [96], which provided a unified and consistent approach to financial liquidity and liquidity risk. She moved from the academic literature that treated the different concepts of liquidity in a rather fragmented way (central bank liquidity in the context of monetary policy, market liquidity in asset-pricing models, funding liquidity in the cash management framework) by concentrating, condensing and reinterpreting the linkage between these broad liquidity types.

Box 2.1. How do reserve requirements work?

Commercial bank money is generated through the fractional reserve banking practice, where banks keep only a fraction of their demand deposits in reserves, such as cash and other highly liquid assets, and lend out the remainder, while maintaining the obligation to redeem all these deposits upon demand. The process of fractional reserve banking has the cumulative effect of money creation by commercial banks, as it expands money supply (cash and demand deposits) beyond what it would otherwise be. Because of the prevalence of fractional reserve banking, the broad money supply of most countries is a multiple larger than the amount of base money created by the country's central bank. That multiple (called the money multiplier) is determined by the reserve requirement or other financial ratio requirements imposed by financial regulators.

2.2 CENTRAL BANK LIQUIDITY

By using Williamson's definition (see [114]) liquidity is “the ability of an economic agent to exchange his existing wealth for goods and services or for other assets”. It is a concept of flows, exchanged among the agents of the financial system, like central banks, commercial banks and market players. Obviously, the inability of the agent to realize or settle these flows leads to his illiquidity. The liquidity may be seen as the oil greasing the wheels of the financial system, so that they work in a frictionless and costless way.

Central bank liquidity can be defined as (see [96]) “the ability to supply the flow of the monetary base needed to the financial system”: the monetary base, or base money or M0, comprises banknotes in circulation and banks' reserves with the central bank. In accordance with the monetary policy stance in terms of the level of key policy rates, this type of liquidity results from managing the central bank's balance sheet.

The main components on the liabilities side are net autonomous factors and reserves. Net autonomous factors consist of transactions that are out of control according to the monetary policy function: for the Eurosystem they are banknotes in circulation, government deposits, net foreign assets and “other net factors”. Reserves are cash balances owned by banks and held by the central bank to meet banks' settlement obligations from interbank transactions and to fulfil their reserve requirements.

Box 2.2. The monetary corridor

A central bank steers short-term money market rates by signalling its monetary policy stance through its decisions on key interest rates and by managing liquidity conditions in the money market. The central bank acts as a monopoly supplier of the monetary base, needed by the banking system to meet the public demand for currency, to clear interbank balances and to meet the requirements for minimum reserves. For instance, the ECB uses two different types of operation to implement its monetary policy: open market operations (OMOs) and standing facilities (SFs). OMOs include main refinancing operations (MROs), long term refinancing operations (LTROs) and fine-tuning operations (FTOs). Through MROs, the ECB lends funds to its counterparties against adequate collateral on a weekly basis. Currently, this lending takes place in the form of reverse repo transactions or loans collateralized by a pool of assets, conducted at fixed rate (the refi rate) with full allotment allocation.

In recent years, auctions have been conducted for an ex ante unknown allotment at competitive rates, floored by the refi rate. In order to control the level and reduce the volatility of money market interest rates, the ECB also offers two SFs to its counterparties, both available on a daily basis on their own initiative: the marginal lending facility (borrowing of last resort at a penalty rate against eligible collateral for banks) and the deposit facility (lending money to the central bank at a discounted rate). As a result, financial institutions used to activate both facilities only in the absence of other alternatives. In the absence of limits to access these facilities (except for the available collateral in case of marginal lending), the marginal lending rate and the deposit facility rate provide a ceiling and a floor, respectively, for the corridor within which the unsecured overnight rate can fluctuate.

Both demand for banknotes and reserve requirements create a structural liquidity deficit in the financial system, thereby making it reliant on central bank refinancing through its open market operations (OMOs). Credits deriving from these operations represent the assets side of the central bank's balance sheet. Ideally, the central bank tends to provide liquidity equal to the sum of the autonomous factors plus the reserves, in order to compensate its assets and liabilities, and manages its OMOs so that the very short-term interbank rates remain close to its target policy rate.

Central bank liquidity should not be confused with macroeconomic liquidity. The latter refers to the growth of money, credit and aggregate savings: it represents a broader aggregate and includes the former. A central bank can only influence the latter by defining the former.

Does central bank liquidity risk exist? As a central bank can always dispense all the monetary base needed, it can never be illiquid: therefore, this kind of risk is non-existent. Ideally, a central bank should only become illiquid if there was no demand for domestic currency. In this case the supply of base money from the central bank, even if available, could not materialize, such as occurred in cases of hyperinflation or in an exchange rate crisis. Obviously, the absence of liquidity risk does not mean that a central bank, in its role of liquidity provider, could not incur costs related to the counterparty credit risk linked to collateral value, to the wrong signalling of monetary policy or to the moral hazard generated by emergency liquidity assistance in turbulent periods.

2.3 FUNDING LIQUIDITY

Funding liquidity can be defined as (see [96]) “the ability to settle obligations in central bank money with immediacy”.

This definition stresses the crucial role played by central bank money in settling bank transactions: in most developed economies, large-value payment and settlement systems rely on central bank money as the ultimate settlement asset. Therefore, the ability of banks to settle obligations means the ability to satisfy the demand for central bank money. The latter is determined by central banks and is beyond the control of a single bank, which by itself can create only commercial bank money through the fractional reserve banking practice.

The funding liquidity risk1 is the possibility that over a specific horizon the bank could become unable to settle obligations with immediacy. Ideally and in line with other risks, we should measure this risk by the distribution summarizing the stochastic nature of underlying risk factors. Unfortunately, such distributions cannot be easily estimated because of lack of data.

It is worth highlighting that funding liquidity is essentially a binary concept: a bank can either settle obligations or it cannot, and it is always associated with one particular point in time. On the other hand, funding liquidity risk can take infinitely many values as it is related to the distribution of future outcomes: it is forward looking and measured over a specific horizon.

A letter written by the Bundesbank's Jens Weidmann to the ECB president, Mario Draghi, in February 2012 stressed the role of so-called TARGET2 imbalances as a destabilizing factor for the financial system. The TARGET2 (Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross-settlement Express Transfer) system allows banks to settle payments between each other through national central banks' accounts. One characteristic of the system is that payments from one bank to another in a different eurozone country are processed through the respective national central banks (NCBs): claims among NCBs resulting from cross-border payments are not necessarily balanced. If payments predominantly flow in one direction, obviously receiving central banks' claims will continue to rise, creating ever-growing imbalances in the TARGET2 system: in recent years the Bundesbank, and to some extent the Banque de France and the Nederlandsche Bank, have recorded significant net claims against central banks in the periphery.

Peripheral countries partly ran very sizable current account deficits, which were financed through borrowing from core countries, mainly through the banking system. These loans were privately funded and, although processed through the TARGET2 system, did not lead to imbalances. As banks in the core economies were no longer willing to extend credit to peripheral banks, NCBs in the periphery stepped in and refinanced peripheral banks. Consequently, they financed the current account deficits of peripheral countries. It is this replacement of privately lent money through central bank funding that led to the rise in net claims of core NCBs against peripheral NCBs. As long as peripheral NCBs are able to replace private funding—the limiting factor is the amount of collateral that can be pledged—there is no additional risk due to TARGET2 imbalances. These imbalances can arise simply by tightening funding conditions for banks that led to stronger reliance on the central bank as a funding source, as experienced dramatically by Greece, Ireland and Portugal over the last two years. By increasing its liquidity provisions to eurozone banks, the Eurosystem also inevitably increased the credit risk it faces, despite the various haircuts applied to the collateral pledged.

Potential losses are distributed among the NCBs regardless of where they materialize: the rise in TARGET2 imbalances has increased the risk for core NCBs only to the extent that without these imbalances the liquidity provision of peripheral banks would have been smaller. However, core NCBs face one specific risk that can be traced back to TARGET2 imbalances, and this refers to the possibility that a country might decide to leave the euro area. In such a scenario, the net claims the remaining NCBs have acquired vis-à-vis that country reflect a genuine risk that would not exist without these imbalances. This could—in the extreme case of a total breakup of the euro area, and assuming that peripheral NCBs could not repay their liabilities—mean that the losses would materialize on the Bundesbank's balance sheet: hence the warning of Jens Weidmann. Hopefully, the pledge of Mario Draghi “to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” made in London in July 2012 and in September 2012 the consequent announcement of the Outright Monetary Transaction (OMT) program finalized to buy an unlimited amount of Euro government bonds under strict conditionality should have reduced the tail risk about a euro breakup.

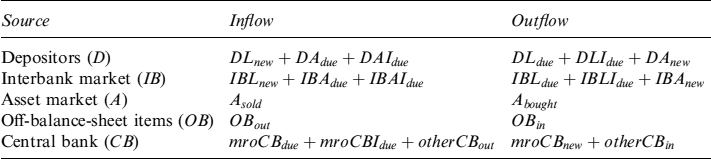

Table 2.1. Funding sources of inflows and outflows for SIFI

In order to match its funding gap a bank can use different liquidity sources. It can get liquidity from depositors, who entrust their savings to the banking system. It can use the market as a liquidity source, through assets sale, securitization or loans syndication. Moreover, it can operate on the interbank market, by dealing unsecured or secured deposits. Finally, as is known, a bank can get liquidity directly from the central bank through OMOs by posting eligible collateral. Typically, funding liquidity risk depends on the availability of these four liquidity sources, and the ability to satisfy the budget constraint over the respective period of time.

Let us define the cash flow constraint as:

cf− ≤ cf+ + MS

where cf− is the amount of outflows (negative cash flows), cf+ is the amount of inflows (positive cash flows) and MS is the stock of money.

This constraint has to hold in each currency, but we can ignore currency differences under the hypothesis that funding liquidity can be easily transferred from one currency to another as long as foreign exchange swap markets are properly functioning.

In Table 2.1 we summarize the key components and the main funding sources for inflows and outflows of money for a systemically important financial institution (SIFI). To reduce notation to the minimum the time subindex has been dropped for each factor.

The first source is defined by the behaviour of depositors. A bank receives an inflow when a borrower pays back the amount (DAdue) and/or the interests (DAIdue) of his loan, or when it receives new deposits (DLdue). Outflows can derive from money withdrawn by depositors (DLdue), interest paid on deposits (DLIdue) or a new loan issuance (DAnew). Not all depositors' withdrawals have to be considered, but only those which lead to a change in central bank liquidity balance. In other words, if consumer X pays company Y and both have an account at the same bank, this money transfer gets settled in the bank's own money and does not change its central bank liquidity. Otherwise, if company Y has an account with another bank, the transfer between banks has to be settled in central bank money.

The second source is the interbank market, where banks used to trade unsecured and secured funding. Basically, we are talking about the same kind of inflows and outflows already defined (IBLnew, IBAdue, IBAIdue, IBLdue, IBLIdue, IBAnew), but to distinguish between an interbank player and private depositor is important because their behaviour is significantly different. The latter is generally very sluggish to react and is not able to monitor a bank's soundness with efficacy, whereas the former is going to adjust his preferences continuously. A further important difference between the private sector and the interbank market is that all money transfers among large banks are always settled in central bank money through a real-time gross settlement system. For this kind of analysis it does not matter whether interbank deposits are secured or not, therefore repo transactions are included in interbank flows.

Box 2.4. Some definitions of funding liquidity

Other definitions of funding liquidity have been made available by practitioners and academics so far.

According to Nikolau [96] and Brunnermeier and Pedersen [40], amongst others, funding liquidity can be viewed as the ability to raise cash at short notice either via asset sales or new borrowing. This kind of definition seems to be more appropriate for counterbalance capacity. Whilst it is the case that a bank can settle all its obligations in a timely fashion if it can raise enough central bank money at short notice, the reverse is not always true as a bank may well be able to settle its obligations as long as its current stock of central bank money is large enough to cover all outflows.

The IMF (2008) defines funding liquidity as “the ability of a solvent institution to make agreed-upon payments in a timely fashion”. This reference to solvency has to be carefully analysed because it is important to distinguish between liquidity and solvency, as welfare losses associated with illiquidity arise precisely when solvent institutions become illiquid.

The definition of the Basel Committee of Banking Supervision [99] for funding liquidity is “the ability to fund increases in assets and meet obligations as they come due, without incurring unacceptable losses”. The second part is rather related to funding liquidity risk, but it is omits to define what “unacceptable losses” really means.

Asset sales/purchases are the third source of inflows and outflows of liquidity. We consider both asset sales/purchases from the trading book and from the banking book. Practically, securities held for trading can often be traded on organized exchanges in relatively liquid markets, while assets held to maturity used to be sold and purchased via securitization programmes “over the counter”. This activity requires time and effort, and delivers results over a longer period in a less liquid market, especially during stressed times.

These two main market liquidity sources (i.e., the interbank market, where liquidity is being traded among banks, and the asset market, where assets are being traded among financial agents) have to be carefully analysed because of their important role in a bank's funding strategy.

2.4 MARKET LIQUIDITY

Continuing our discussion of liquidity sources let us introduce the third type of liquidity. Market liquidity can be defined as (see [96]) “the ability to trade an asset at short notice, at low cost and with small impact on its price”. In a deep, broad and resilient market any amount of asset can be sold anytime within market hours, quickly, with minimum loss of value and at competitive prices.

Box 2.5. The funding liquidity risk for a leveraged trader

Let us consider the case of a leveraged trader (such as a dealer, a hedge fund or an investment bank) who is used to borrowing liquidity in the short term against the purchased asset as collateral. He is not able to finance the entire market value of the asset, because a margin or haircut against adverse market movements is required by market players for secured transactions. This difference must be ideally financed by the trader's own equity capital. Haircuts are financed in the short term because they have to be adapted on a daily basis, while equity capital and longer term debt financing are more expensive and difficult to obtain when the firm suffers a debt overhang situation. As a consequence, traders avoid carrying much excess capital and are forced to de-leverage their positions by increased margins or haircuts.

Financial institutions that rely on commercial paper or repo instruments to finance their assets have to roll over their debt continuously. A drying up of the commercial paper market is equivalent to margins increasing to 100%, just as if the firm becomes unable to use its assets as a basis for raising liquidity. A similar effect is produced by withdrawals of demand deposits for a commercial bank or by capital redemption from an investment fund.

To sum up we have already identified three forms of funding liquidity risk:

- margin/haircut funding risk

- short-term borrowing rollover risk

- redemption risk

All these risks will be analysed in more depth in the second part of this book.

A market is deep when a large number of transactions can occur without affecting the price, or when a large number of orders are in the order books of market makers at any time. A market is broad if transaction prices do not diverge significantly from mid-market prices. A market is resilient when market price fluctuations from trades are quickly dissipated and imbalances in order flows are quickly adjusted.

We can refer to market and funding liquidity in the following way: market liquidity is the ability to transfer the entire present value of the asset's cash flows, while funding liquidity is a form of issuing debt, equity, or any other financial product against a cash flow generated by an asset or trading strategy.

Market liquidity risk relates to the inability to trade at a fair price with immediacy. It represents the systemic, non-diversifiable component of liquidity risk. It implies commonalities in liquidity risk across different market sectors, such as bond and equity markets, and requires a specific pricing. From this specific point of view liquidity risk has often been regarded in the asset-pricing literature as the cost/premium that affects the price of an asset in a positive way, by influencing market decisions through optimal portfolio allocation and market practices by reducing transaction costs.

2.5 THE VIRTUOUS CIRCLE

These three liquidity types are strongly linked, so they can easily lead to a virtuous circle by fostering financial stability during normal periods or to a vicious circle by destabilizing markets during turbulent periods.

Under normal conditions the central bank should provide a “neutral” amount of liquidity to the financial system to cover its structural liquidity deficit and balance liquidity demand and supply. Banks should receive central bank liquidity and, through interbank and asset markets, should redistribute it within the financial system to liquidity-needing players, who ask for a liquidity amount to satisfy their liquidity constraint. After this redistribution on an aggregate basis, the central bank should calibrate the new liquidity amount to satisfy liquidity demand, and the virtuous circle starts again.

In this scenario each liquidity type plays a specific role. Central bank liquidity represents provision of the amount of liquidity to balance aggregate demand and supply. Market liquidity warrants the redistribution and recycling of central bank liquidity among financial agents. Funding liquidity defines the efficient allocation of liquidity resources from the liquidity providers to the liquidity users. As each liquidity type is unique in the financial system, the three liquidity types can only play their specific role by relying on the other two working well and the system overall being liquid. This means that the neutral amount of liquidity provided by the central bank can flow unencumbered among financial agents as long as market liquidity effectively recycles it and funding liquidity allocates it within the system in an efficient and effective way. Markets are liquid because there is enough liquidity in the financial system on aggregate (i.e., there is no aggregate liquidity deficit due to the supply from the central bank) and each counterparty asks for liquidity according to their specific funding needs without hoarding additional liquidity provisions. Obviously, funding liquidity depends on the continuous availability of all funding liquidity sources, so a bank is going to be liquid as long as it can get enough liquidity from the interbank market, the asset market or the central bank. These are all preconditions typical of frictionless and efficient markets. In fact, if markets are efficient, banks have recourse to any of the available liquidity options, so the choice will depend only on price considerations.

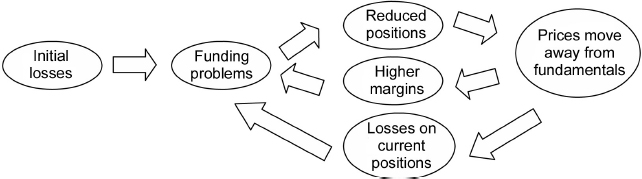

2.6 THE VICIOUS CIRCLE

The links described until now can be distorted in cases of liquidity tensions and are likely to serve as risk propagation channels, by reverting from a virtuous circle to a vicious spiral in the financial system. Each liquidity type is subject to a specific liquidity risk, which lies in coordination failures among economic agents such as depositors, banks or traders, due to asymmetric information and incomplete markets.

Look at funding liquidity risk, which is likely to be the first source for idiosyncratic and systemic instability. Funding liquidity risk lies at the very heart of banking activity because banks develop their business basically by means of maturity transformation to fund illiquid long-term loans with liquid short-term deposits.

More specifically, banks provide liquidity to the financial system through the intermediation of economic agents. They provide illiquid loans to investors, who are funded with liquid deposits from depositors. In so doing, banks create funding liquidity for financial and private sectors and promote the efficient allocation of resources in the system.

Box 2.6. Where do bank activity benefits come from?

By properly planning deposit-taking and lending activities, banks are able to create an economy of scale that reduces the amount of costly liquid assets that are required to support loan commitments. Given the existence of some liability guarantees, such as deposit insurance, central bank liquidity availability and targeted liquidity assistance, many papers ([71], amongst others) provide empirical evidence of negative covariance between deposit withdrawals and commitment takedowns, and argue that deposits can be viewed as a natural hedge, up to a certain point, against systematic liquidity risk exposure stemming from issuing loan commitments and lines of credit.

From a systemic point of view, the tradeoff for this activity is the inherent liquidity risk linked to the asset–liability maturity mismatch. This mismatch can generate instability in the bank's role of liquidity provider on demand to depositors (through deposit accounts) or borrowers (through committed credit lines), if not mitigated by liquid asset buffers. As liquid assets usually yield low returns, banks have to continuously redefine their investment strategy between low-yield liquid assets and high-yield illiquid ones.

The worst output of funding liquidity risk is obviously represented by a bank run, which ultimately leads to the bank's failure. Funding liquidity risk could represent a cause of concern for regulators when it is transmitted to more than one bank, because it, becoming systemic, can increase market liquidity risk to the interbank and the asset market.

Focusing on the interbank market, individual bank failures can shrink the common pool of liquidity which links the financial system and can propagate the liquidity shortage to other banks, leading to a complete meltdown of the system, as occurred with Lehman's default. Such a propagation mechanism is reinforced by the extensive inter-linkages among banks, like the interconnected bank payment systems, balance sheet linkages, or cross-holdings of liabilities across banks represented by interbank loans, credit exposures managed by margin calls, or committed credit lines. In some cases, an informational spillover to the interbank market could lead to generalized bank runs. Such interlinkages represent crisis propagation channels in the presence of incomplete markets and asymmetric information, as explained in the previous chapter. They easily stimulate fears of counterparty credit risk when the absence of a complete set of contingent liabilities (even more crucial for the completion of markets and to provide effective tools for hedging against future liquidity outcomes) combines with information asymmetries about the illiquidity and the insolvency of banks.

According to this framework, insolvent banks may act as merely illiquid ones and decide to free-ride on the common pool of liquidity in the interbank market: they can then engage in risk-prone behaviour by underinvesting in liquid assets and gambling for assistance. Ultimately, this form of moral hazard can lead to adverse selection in lending, with insolvent banks, mistaken as simply illiquid, granting liquidity, instead of solvent but illiquid ones; in limited commitment of future cash flows; in liquidity hoarding, because of doubts about their own ability to borrow in the future. Eventually, some banks would be rationed out of the system, and few remaining cash-giver banks could take advantage of their oligopoly position by underproviding interbank lending in order to exploit the others' failure or to increase the cost of funding for liquidity-thirsty banks.

Box 2.7. A bank's worst nightmare

A bank run is defined as a situation where depositors decide to liquidate their deposits before the expected maturity of the investment, leading to increased demand for liquidity that the bank is not able to satisfy, due to the fractional reserve banking practice. It can materialize when bad expectations among economic agents lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, such as when depositors believe other depositors will run. When news about the borrower increases uncertainty among depositors, a bank run can occur because it is optimal to pre-empt the withdrawals of others by borrowing first. For instance, late movers may receive less if the run occurs for fundamental reasons (investing in bad projects could reduce the net worth of the bank) or if it occurs for funding liquidity reasons. In this case, early withdrawals force a bank to liquidate long-maturity assets at fire sale prices: it leads to an erosion of the bank's wealth and leaves less for those who withdraw their money late.

In the current financial world deposit insurance has made bank runs less likely (the only recent case was Northern Rock), but modern runs can occur at higher speed than in the past and in different ways. On May 15, 2012 the president of Greece, Karolos Papoulias, announced that he had been warned by the central bank that depositors had just withdrawn EUR1.2 billion in the two previous days, after the announcement of another poll in mid-June. These runs started not with a queue of people lining up to withdraw cash but with clicks of a computer to transfer money abroad or to buy bonds, shares or other assets.

Modern forms of bank runs are represented by not rolling over commercial paper for the issuer of ABCP, pulling out sizable amounts of liquid wealth parked by hedge funds for their prime brokers, by increased margins or additional liquidity buffers on collateralized products for downgraded institutions or by capital redemption requests for an investment fund.

In the case of severe impairment of the interbank channel, market liquidity risk can easily propagate to the asset market as banks may look for liquidity through fire sales, with relevant impacts on asset prices and liquidity. The propagation process runs through the assets side of banks' balance sheets by means of portfolio restructuring which needs to find buyers for distressed assets in order to avoid more expensive project liquidation. In the case of incomplete markets, the supply of liquidity is likely to be inelastic in the short run and financial markets may only have limited capacity to absorb assets sales, with prices likely to fall below their fundamental value. This results in increased volatility of asset prices, a huge reduction in market depth, and distressed pricing, where the asset market clears only at fire sale prices.

2.7 SECOND-ROUND EFFECTS

Unfortunately, up to now we have only summarized the first-round effects of a vicious circle related to a liquidity crisis. The strong linkages existing between market and funding liquidity are likely to produce second-round effects as well, which may deepen market illiquidity and lead to downward liquidity spirals, with outcomes that can easily outweigh in magnitude the original shock.

In the current financial system many assets are marked-to-market and subject to regulations. In this environment, asset price movements produce changes in the net worth of the asset side of the balance sheet and require responses from financial intermediaries who have to adjust the size of their balance sheets according to their leverage targets, thereby effectuating speedy transmission of the feedback effect.

The combination of new lower prices, solvency constraints and capital adequacy ratios defined by regulators, and internally imposed risk limits, can require further asset disposals. Then distressed pricing can become worse due to further frictions in trading: trading regulations, limits to arbitrage and predatory trading could renew the vicious circle and exacerbate the downward spiral.

Moreover, sharp declines in asset prices lead to a loss of value for the collateral received/paid versus derivative portfolio exposure or securities lending activity. Changes in collateral values result in adjusted values for margin calls and haircuts. Under such circumstances, banks are therefore vulnerable to changes in the value and market liquidity of the underlying collateral, because they have to provide additional collateral, in the form of cash or highly liquid securities, at short notice, which affects their funding liquidity risk. The more widely collateralization is used, the more significant this risk becomes, especially as market price movements result in changes in the size of counterparty credit exposure. As required margins and haircuts rise, financial institutions have to sell even more assets because they could need to reduce their leverage ratio, which is supposed to be held constant during the loss spiral.

As explained by Brunnermeier and Pedersen [41], the loss spiral is “a decline in the assets' value which erodes the investors' net worth faster than their gross worth and reduces the amount that they can borrow”. It depends on the expected leverage ratio of the firm.

Let us suppose that an investor works with a constant leverage ratio of 10. He buys USD100 million worth of assets at a 10% margin: he finances only USD10 million with his own capital and borrows the other USD90 million. Now suppose that the value of the asset declines to USD95 million. The investor has lost USD5 million and has only USD5 million of his own capital remaining because of the mark-to-market. In order to keep his leverage ratio constant at 10, he has to reduce the overall position to USD50 million, which implies selling assets worth USD45 million exactly when the price is low. This sale depresses the price further, inducing more selling and so on. (This example was suggested by Brunnermeier [38])

Figure 2.1. The loss spiral and margin spiral

Source: Brunnermeier and Pedersen [41]

The spike in margins and haircuts, related to significant price drops, leads to a general tightening of lending. It is produced by two main mechanisms: moral hazard in monitoring and precautionary hoarding.

Lending is basically intermediated by banks, which have good expertise in monitoring borrowers' investment decisions due to their own sufficiently high stake. Moral hazard arises when the net worth of the stake of intermediaries falls because they may be forced to reduce their monitoring effort, pushing the market to fall back to a scheme of direct lending without proper monitoring.

Precautionary hoarding is required when lenders are afraid that they might suffer from interim shocks and that they will need additional funds for their own projects and trading strategies. The size of this hoarding depends on the likelihood of interim shocks and the availability of external funds. In the second half of 2007, when conduits, SIVs/ SPVs and other off-balance-sheet vehicles looked likely to draw on committed credit lines provided by the sponsored banks, each bank's uncertainty about its own funding needs skyrocketed. In the meantime, it became more uncertain whether banks could tap into the interbank market since it was not known to what extent other banks faced similar problems.

A visual representation of the loss spiral is in Figure 2.1.

The new business model of credit, based on risk transfer techniques, has strengthened linkages between market and funding liquidity, leading to more direct contagion channels and faster propagation of second-round effects. Securitization is broadly used by banks to manage their credit and funding liquidity risk, by transferring credit risk off its balance sheet and creating a larger and more disperse pool of assets, which while satisfying various risk appetites has made banks more dependent on market funding, through market structures like special purpose vehicles. Nowadays, banks' incentives and ability to lend are expected to depend on financial market conditions to a larger extent than in the past, when banks were overwhelmingly funded via bank deposits. This intensifies the link between market liquidity and funding liquidity risk and eases the propagation of downward liquidity spirals.

2.8 THE ROLE OF THE CENTRAL BANK, SUPERVISION AND REGULATION

The first and second-round effects of the aforementioned vicious circle can potentially lead to systemic failures within the financial system, with negative effects for taxpayers and the real economy. The cost to fix ex post systemic liquidity risk with its potential to destabilize the whole financial sector could be dramatic, as was shown to be the case with Lehman's failure, so in such cases emergency interventions and liquidity provisions to halt negative spirals and restore balance appear to be very useful.

Box 2.9. Should a central bank provide emergency liquidity through TLA or OMOs?

By TLA we mean targeted liquidity assistance provided to individual institutions through the discount or marginal lending facilities, whereas OMO stands for open market operations, which lend the monetary base to the market as a whole. Both solutions can produce moral hazard, the choice therefore depends on the functioning of the interbank market and the goals of the monetary policy.

OMOs are mainly used in order to implement monetary policy. They are useful when it is necessary to target some market rates, such as during liquidity crunches when high market rates can increase liquidation costs or during generalized liquidity shortages when support is required by the market as a whole. They allow avoiding the stigma associated with borrowing from the discount window, but mainly rely on the well-functioning interbank market to redistribute liquidity effectively into the system. On the contrary, banks are forced to ask for more liquidity than needed on a precautionary basis.

In the case of an inefficient interbank mechanism, TLAs could be a more flexible tool to tackle liquidity deadlocks because, in the form of a discount window, they allow some specific banks to be financed in the fastest and most direct way. In doing so, they avoid the moral hazard linked with OMOs, where distressed banks and “greedy” investors compete for excess funding provided during the crisis, given frictions in the interbank market.

In its role of guarantor—not only of financial stability, but of the entire economy—a central bank should be in a position to tackle systemic liquidity risk. Its role is unique among other financial supervisors and regulators, due to the potential size of its balance sheet and its actual immunity to bankruptcy. Acting as an LLR (lender of last resort) a central bank can activate tools to enable market stabilization, by preventing panic-induced collapses of the banking system and reducing the cost of bank runs and forced liquidations in thin markets. The most effective tools are liquidity provision mechanisms via OMOs or TLA.

Unfortunately, when acting as an LLR, a central bank can only focus its intervention on shock amortization and not on shock prevention. It tries to minimize secondary repercussions of financial shocks, such as contagion, spillover or domino effects, by providing temporary injections of central bank liquidity with the purpose of breaking the loop between market and funding liquidity risk, so that downward liquidity spirals would fail to further distress markets. In doing so, however, a central bank has not guaranteed success over the financial crisis: it cannot tackle the root cause of liquidity risk because its very function is hampered by incomplete information.

In fact, the potential benefits are limited by the fact that a central bank cannot distinguish between illiquid and insolvent banks with certainty. This inability can create bidirectional links from central bank liquidity to funding and to market liquidity, and also hurt the central bank itself. By rescuing insolvent institutions, which do not deserve its assistance, a central bank is implicitly penalizing solvent but illiquid banks, mainly because it is increasing their cost of funding. This could render them potentially unable to borrow or to repay loans, thereby enhancing their funding liquidity risk. During turbulent times, markets could assume the implicit central bank liquidity provision as an insurance or safety net for financial institutions. Misallocation of central bank liquidity can promote excessive risk-taking by banks and create moral hazard, by stimulating risk-prone behaviour by insolvent institutions that can gamble for resurrection with central bank money. Moreover, lending to undeserving institutions could ultimately turn against a central bank's stabilizing role, because the recovery of the financial system could be more uncertain, lengthy and expensive. It can require higher costs of maintaining the financial safety net, in terms of credit risk in the central bank's balance sheet and the ability to achieve its monetary policy objectives.

Box 2.10. A revision of Bagehot's view

Whether and how a central bank should intervene to tackle systemic liquidity risk is a topics well analysed in the literature (see, for example, [66]). According to [13], “the central bank should be known to be ready to lend without limits to any solvent bank against good collateral and in penalty rates”, so that banks do not use them to fund their current operations. Only in the presence of a well-functioning, deregulated, uncollateralized interbank market [74] could central bank intervention be effective in providing emergency liquidity assistance.

A fascinating debate has begun about the “to be known” part, and concerns the dichotomy between constructive ambiguity and pre-committed intervention (see [106]). The latter may act as public insurance against aggregate risk in an incomplete market economy, but at the cost of fuelling expectations of insurance for financial institutions against virtually all types of risk. The former should strengthen market discipline and mitigate the scope for moral hazard, as long as it is coupled with procedures for punishing managers and shareholders for imprudent strategies.

This debate can be overcome by providing liquidity at penalty rates: this would discourage insolvent banks from borrowing continuously, as if they were merely illiquid, and should help to discern illiquid from insolvent banks. In turbulent times, however, recourse from the banking sector to emergency assistance could become significant, and applying penalty rates could increase the liquidity cost for illiquid but solvent banks. Perhaps the most stimulating debate has been focused on the part related to “lend to (only) any solvent bank” is perhaps the most stimulating one. Obviously, lending only to solvent banks would be optimal because it would minimize intermediation costs and reduce moral hazard. Unfortunately, as previously said, screening ex ante between insolvent and illiquid banks is almost impossible such that, with incomplete and costly information, the only way is to lend to any bank at a pooled rate, but this leads to adverse selection and moral hazard in emergency times.

Lending only against good collateral could facilitate the screening of insolvent from illiquid banks, because the probability that an illiquid, but solvent bank lacks enough good collateral is quite small. Unfortunately, the devil is in the details again, because good collateral may not be abundant or available during periods of crisis, when a large part of securities are likely to be hampered by rating agency downgrades. In these cases, accepting only good collateral (namely, with a minimum rating above the threshold used in normal times), transparent to value and easy to liquidate, could ultimately come into conflict with the authorities' responsibility for financial stability.

Accepting a wider range of collateral, as all central banks have done in recent years, is conducive to improving market liquidity conditions, because their willingness to accept certain asset classes as collateral will in turn affect the liquidity or, at least, the marketability of such assets. The counterargument is related to the worst eligible collateral delivery option sold for free to the banking sector, while allowing it to access the market with its better collateral. However, the prevailing view suggests that a central bank should be willing to accept some losses linked to the widening of eligible criteria, in order to address severe interbank market dislocations and minimize the social costs of systemic failures.

Central banks have little choice but to undertake a cost tradeoff analysis. On the one hand, a central bank faces the danger of welfare costs due to costly bank runs and forced liquidations; on the other hand, it has to face spiralling costs linked to excessive risk-taking, the ignition of future liquidity crises and increased credit risk in its portfolio. During crises a central bank can only give temporary support to the financial system, until the structural causes of liquidity risk can be dealt with. It provides significant aid, but is definitely not a panacea. As long as other weapons, like more supervision and tougher regulation, are not used to tackle the causes of the crisis, the temporary liquidity injected by a central bank can only break the vicious circle and risk, in the long run, its stabilizing role.

Effective supervision—not only official and centralized, but also in the form of interbank peer-monitoring—can balance information asymmetries because it facilitates the distinction between illiquid and insolvent banks. Obviously, effective implementation of peer-monitoring may be difficult, due to commitment problems by governments. In those cases regulation, in the form of liquidity requirements and a binding contingency plan, may be a useful way to address some issues. Efficient supervision and regulation can also support the development of new financial products that may contribute to reducing incomplete markets. To the extent that liquidity risk is endogenous in the financial system, the quality and the effectiveness of supervision and regulation in the financial system impact both the scope and the efficiency of central bank liquidity.

2.9 CONCLUSIONS

In this chapter we analyzed the complex and dynamic linkages between market liquidity and funding liquidity, which are able to enhance the efficiency of the financial system in normal periods, but can destabilize financial markets in turbulent times. Central banks can only halt temporarily the negative effects of the vicious circle and restore balance, but they are not able to tackle the root causes of systemic liquidity risk, which rest in departure from complete markets and the symmetric information paradigm.

In order to fix these issues, is it of the essence to minimize asymmetric information and moral hazard between financial players through effective monitoring mechanisms of the financial system: supervision and regulation are the fundamental weapons needed to wage war against liquidity crises, by increasing the transparency of liquidity management practices. Nevertheless, fitting the optimal size of supervision and regulation to a financial system is a challenging task, because gathering data for supervision and establishing, implementing and monitoring regulation can be very expensive. In order to promote better transparency and create economies of scale in acquiring information to reduce the cost of monitoring banks, a central bank could consolidate official supervision and regulation by taking them into its own hands. This would make it easier to distinguish illiquid from insolvent agents, to calibrate interventions carefully and therefore to reduce its costs.