Chapter 11

Stepping into the Real World: Oligopoly and Imperfect Competition

In This Chapter

![]() Considering the criteria for an oligopoly

Considering the criteria for an oligopoly

![]() Modeling firms’ strategic behavior in oligopoly

Modeling firms’ strategic behavior in oligopoly

![]() Differentiating products to soften competition

Differentiating products to soften competition

Oligopoly is the name economists give to a type of market with only a few firms (it comes from the Greek word oligos meaning few). The classic example of an oligopoly is the airline industry, where a few airlines compete among themselves for customers, and the bulk of the domestic market is locked up among the four largest competitors: American, Delta, United Airlines, and Northwest. But oligopoly is visible everywhere, in industries as different as cable television services, computer and software industries, cellular phone services, and automobiles.

One of the ways in which economists analyze oligopoly is by comparing it with other market structures. Compared to perfect competition, described in Chapter 10, consumers don’t get as good a deal. But compared to monopoly (which has no competition, see Chapter 13), they do better under oligopoly.

In this chapter, we discuss the basic attributes of an oligopolistic market, three ways of describing how firms operate in such a market, and how firms are able to differentiate themselves from their rivals and gain market power.

Outlining the Features of an Oligopoly

The first thing you have to do when looking at oligopoly is describe the key characteristics that make a given market an oligopoly. Besides having only a few firms in the market, here are some other features to note:

- Firms have market power and can affect market prices: The demand curve facing a firm in this case is downward-sloping rather than a flat line (as for perfect competition — check out Chapter 10).

- Firms, as ever, are rational profit maximizers: They set prices or quantities where marginal revenue equal marginal cost (see Chapter 3).

- Firms interact by anticipating how their rivals will react to their decisions: These guesses about their rivals’ behaviors affect the price that a firm will charge or the quantity it will supply.

- Entry into the market typically incurs sunk costs: Sunk costs are costs, such as advertising or product development, that have no recoverable value after the cost has been expended. These make entry costly and exit not costless.

- Consumers are rational utility maximizers: Therefore, demand works in the same way as in Chapter 9.

- Innocent: Large capital investments that have no resale value. For example, setting up a manufacturer of aircraft costs a lot of money for specific plants and equipment.

- Strategic: Incumbent firms may engage in costly behavior strategically designed to keep entrants out, including preemptive moves.

- Prohibitive regulations: Such as the result of government allowing only a few licenses to trade in that industry. For example, in 1927 the U.S. government nationalized the airwaves and since then licenses their use. Wireless broadband providers like Verizon and AT&T must bid for the spectrum licenses they use. Television broadcasters, on the other hand, are issued licenses by the Federal Communications Commission.

Discussing Three Different Approaches to Oligopoly

A helpful way to start understanding oligopoly is to consider the special case of a duopoly, where only two firms are operating in the market. After you get the hang of thinking about how two firms interact with each other, you can adapt your modeling to think about the harder cases involving three or more firms.

Investigating how firms interact in a duopoly

- Cournot model: Where quantity is the strategic variable.

- Bertrand model: Where price is the strategic variable or the thing that firms control.

In both models, we assume that firms either choose quantity (Cournot) or price (Bertrand), simultaneously.

Instead of having the two firms make their choices simultaneously, an alternative approach is to let one firm choose first and the other second, or move sequentially. When choices are made sequentially, we are interested in whether there is a first mover advantage.

The Stackelberg model allows one firm to have a potential leadership advantage over the other firm by moving first. We discuss a version where the firm has an advantage over choosing how much to produce, called quantity leadership.

Next you want to work out the equilibrium in each case so that you can compare them — the results are interesting even in a simple model.

Competing by setting quantity: The Cournot model

Imagine the simple scenario of two Canadian lumber companies, Fort William and Port Nelson. Lumber is a useful example because it’s reasonably indistinguishable as a product.

Spelling out customer demand

Begin by looking at customer demand, Q, as a function of market price P. This is something neither company can change. In a quantity-setting model, the firms choose quantities to produce, and price adjusts to clear the market. In a price-setting model, firms set their prices, and consumers decide how much to buy at those prices. For a simple example, suppose a linear demand function:

![]()

Fort William and Port Nelson produce QFW and QN, respectively. The total market size depends on both firms’ production, and so:

![]()

To make things simple, though a little unrealistic, set the model up with a marginal cost (MC) for both firms of zero (this keeps things a little simpler than reality, but as you progress with the model, you can change this assumption and see what happens):

![]()

The last thing is to find an expression for the total revenue of one of the firms. We choose Fort William and use the identity that total revenue equals price times quantity. Knowing the demand function, you can write:

![]()

This gives the total revenue for Fort William as an expression of the total amount of lumber produced by the two firms — allowing you to move on to calculating the profit-maximizing level of production.

Finding the optimum production for Firm 1

The optimum is at MC = MR, so finding the optimum level means setting MR equal to zero (as MC was assumed to be in the preceding section). MR is the change in total revenue when quantity increases by one. In order to find it, take the slope of the expression for total revenue for Fort William.

Beginning with the expression for TRFW, multiply it out to see what all the parts of the expression are:

Finding the slope of this equation with respect to a change in QFW, you get an expression for marginal revenue (MR). You can do so by plotting total revenue for Fort William against its output and taking the slope of the line (but if you trust us, you can go straight there by using calculus):

![]()

Now you know that MC = MR (because the firm is a profit maximizer) and MC is zero in this model, so you know that if you set MR equal to zero and solve for QFW you get:

![]()

Plotting reaction curves for the two firms

You can go through the same reasoning as in the preceding section to get Port Nelson’s reaction function — or you can trust us that it works out as being:

![]()

The next stage is to plot the two reaction functions against each other. Each axis measures the quantity produced of one of the companies. The two reaction curves give the amount of lumber each will produce given the production of the other.

The two lines cross at one unique point (because they’ve been set up as straight lines — so this may not be true if revenue and cost functions were more complex).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Figure 11-1: Cournot equilibrium for two firms.

Seeing why the equilibrium isn’t as good as a competitive market

If you feed back the total output of both firms into the demand curve, you can get an expression for the price each will receive. Market demand is given by P = 30 – Q and total production is equal to 20, and so the price that the market is prepared to pay is 10.

Seeing why the equilibrium isn’t as bad as a monopoly

Suppose the two firms coordinate their decisions so that you can treat them as a monopoly — a single firm that supplies the whole of the market. Then the firms together maximize their revenue based on combined demand.

Collusion among firms in an oligopoly to coordinate on the monopoly outcome is not surprisingly bad for consumers. When firms collude successfully, the result is a cartel and is highly illegal, precisely because it results in a lower quantity produced (and therefore higher prices). Check out Chapter 16 for more on cartels.

Following the leader: The Stackelberg model

Deriving a Stackelberg model for the lumber companies means that one firm sets its optimal production and the other firm reacts to the first firm’s decision. Suppose that Port Nelson is able to be the first mover. What would it produce and how would Fort William react?

Suppose — as before — that the demand curve is given by this:

![]()

Now Port Nelson makes its decision based on what it can predict the follower, Fort William, will do. It predicts Fort William’s behavior by knowing that Fort William will be on its best response or reaction function. Port Nelson can substitute Fort William’s reaction into its own total revenue function:

![]()

![]()

This gives Port Nelson’s revenue function given Fort William’s reaction:

![]()

That looks unwieldy, and so we gather like terms to simplify:

![]()

Find the slope of this line to get marginal revenue for Port Nelson:

![]()

You can now set MR = MC = 0, which gives production for Port Nelson as 15. Now, using Fort William’s reaction function, you can plug Port Nelson’s production back in and get 7.5.

Comparing to the Cournot results where both firms made 10 units (from the preceding section), you instantly see that Port Nelson makes 15 units of lumber and Fort William only 7.5! Also, summing the total output of the two firms, you get 22.5 units rather than the 20 under Cournot conditions. So, if one firm gets to lead and move first, output for the industry as a whole is higher. Plug that into the demand function and you see that this is tantamount to price being lower.

Competing over prices: The Bertrand model

Let’s start at the Cournot outcome (refer to the earlier section “Competing by setting quantity: The Cournot model” and Figure 11-1), in which each firm is selling 10 units at a price equal to 10. Now suppose that the two firms compete in price instead of quantity, each firm sets its price of lumber, and consumers place their orders. Will one of our lumber companies have an incentive to deviate and set a price different from 10?

From the consumer’s perspective, the goods are identical, so if Fort William cuts price to 9, all customers will order from it, the lower-price supplier, and this move is profitable. However, Port Nelson will react and cut price a small amount below Fort William’s. Then it takes the entire market. Neither company wants to be the one quoting higher prices in this scenario.

This finding bears out the important observation that price competition isn’t in the interests of producers in this type of market. If each firm gets the competitive price, profits made are zero and neither producer gets to benefit from the lack of entry.

Comparing the output levels and price for the three types of oligopoly

- Cournot competition: The lowest industry output and highest price appears when firms are Cournot competitors, reacting to their conjecture at what each other’s output will be. The price here isn’t quite as high as under a cartel or a monopoly, but it’s higher than in other types of oligopoly.

- Stackelberg competition: The outcome leads to not quite as high a price and not quite as low an output as Cournot, but it isn’t quite as good as under a competitive market.

- Bertrand competition: The outcome leads to the same price as under a perfect competitively supplied market (and therefore the highest quantity).

In the Stackelberg and Cournot models, equilibrium price exceeds marginal cost, which means that firms make economic profits. In the case of Bertrand competition with undifferentiated products, price hits marginal cost, and therefore firms make zero profits in equilibrium.

Making Your Firm Distinctive from the Competition

In the hard-nosed world of competitive business, firms have a strong incentive to differentiate their products to separate themselves from rivals. Car manufacturers, for instance, produce many different brands of car rather than a single generic item called a car. Even when the goods are relatively homogenous, such as matches or sticky tape, firms still want to identify their product as different from others in consumers’ minds. These strategies can soften competition.

This practice raises a question: At which point are products different enough that thinking about them as being in the same market stops making sense? Economists examine this issue by looking at the cross-price elasticity of demand between two products (for details, check out Chapter 9): The more positive the cross-price elasticity, the more likely the two products are indeed in the same market. Looking at it from the perspective of a firm that wants to make as much profit as possible, branding and making its product different to competitors’ products reduces the cross-price elasticity of demand.

Economists look at these behaviors in two ways:

- They adapt oligopoly models to allow the products to be differentiated.

- They use a model called monopolistic competition, which allows for profitable product differentiation to work in the short run, but not in the long run (because if you hit on a winning formula, someone is bound to copy it).

Reducing the effects of direct competition

- Integrating their supply chains: For instance, selling through preferred partners or through retail networks that they themselves own allows a company to differentiate its product through the retail services it provides. Antitrust laws may prevent firms with dominant market positions from doing this, because of fears of excluding rivals. But otherwise it is fine. A Honda dealership that only sells Honda cars and vans is an example of a producer owning a retailer — what economists call forward vertical integration in the supply chain.

- Branding products: Branding strategies center on advertising and packaging so that consumers identify the products as being different. Sometimes branding is a way to highlight that a product is in fact different — think of detergents, where brands and formulas are interlinked. But sometimes branding exists where products are minimally different — gas, for instance.

- Competing on some other dimension that consumers care about: Location is one such example; returns and payment options are another.

Economists build upon the basic oligopoly models talked about in the earlier section “Discussing Three Different Approaches to Oligopoly” in order to capture the importance of product differentiation and sunk costs. Here are two basic ways:

- Adapt the oligopoly models to include product differentiation with significant barriers to entry. If firms differentiate their products and at the same time incur sunk marketing and advertising costs to communicate these differences to consumers, then price cutting a la Bertrand competition (described in the earlier section “Competing over prices: The Bertrand model”) is muted. Customers will develop loyalty and not switch to lower-priced rivals. Moreover, entry is difficult because of the marketing and distribution costs incurred to reach consumers. Both factors mean firms can make economic profits in a long-run equilibrium.

- For markets where product differentiation is important but barriers to entry are relatively low, economists use a model called monopolistic competition in which entry can occur in the long run. This adaption looks at competition with differentiated products from the perspective of a firm that can make economic profits in the short run, but not in the long run (check out the next two sections for more).

A consequence of barriers to entry is that it enables firms to make long-run economic profits, which is one reason economists tend to dislike them. The thing is, in reality, many industries show a turnover in membership. Although some industries are nice examples of oligopoly with little entry — think of the soft drink industry — others show significant amounts of entry and exit. The car manufacturing industry, for example, has lost names such as the DeLorean, the Nash, and the Oldsmobile, over the years, but gained a Lexus, a Tesla, and a Kia along the way.

Competing on brand: Monopolistic competition

This situation applies to many industries, from cereals — a relatively generic product with some degree of differentiation on brand — to broadcast television. These industries have in common the fact that the firms have to invest continually in their product or their brand — or both — or risk losing their profits to an entrant.

Seeing how brands compete

Firms, as usual, operate where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. They use that to set quantity and receive the price consumers are willing to pay (from the demand curve).

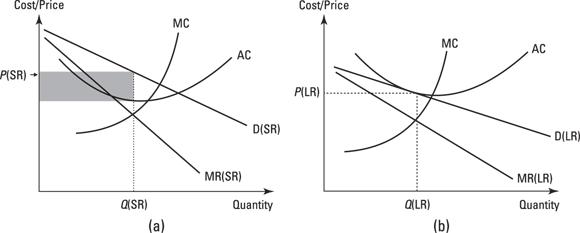

Because firm demand is downward sloping, price or average revenue is greater than marginal revenue, so the firm makes profits in the short run (see the shaded area in Figure 11-2a, with markup being the difference between price and average cost). However, in the long run, in Figure 11-2b, entry has shifted the firm demand curve downwards, and as a result the new equilibrium, though still having the firm producing where MC = MR, results in the firm making no economic profits.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

MC = Marginal cost; AC = Average cost. (a) In the short run: P(SR) = Price in the short run; Q(SR) = Quantity in the short run; MR(SR) = Marginal revenue in the short run; D(SR) = Demand in the short run. (b) In the long run: P(LR) = Price in the long run; Q(LR) = Quantity in the long run; MR(LR) = Marginal revenue in the long run; D(LR) = Demand in the long run.

Figure 11-2: Monopolistic competition – firm equilibrium.

Trading efficiency for diversity: Monopolistic competition for consumers

Compared to a perfectly competitive market, some welfare loss (described in Chapter 13) occurs under monopolistic competition. The monopolistically competitive industry produces less total output than under a competitive market, which means a deadweight loss — a loss of consumer surplus in particular. Figure 11-3 depicts this as a shaded triangle (the area under the demand curve but above marginal cost for units of output not produced).

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

P(LR) = Price in the long run; Q(LR) = Quantity in the long run; MR(LR) = Marginal revenue in the long run; D(LR) = Demand in the long run.

Figure 11-3: Monopolistic competition – deadweight loss.

Certain biases can exist in monopolistic competition. Not every desirable good, from the point of view of consumers, is necessarily produced. In particular, monopolistically competitive industries have a bias against products with a very high elasticity of demand because this makes maintaining the price premium of the brand difficult.

Understanding differentiation: The median voter

To see Hotelling’s reasoning, consider a simple example. Fifth Avenue in Manhattan between 49th Street and 60th Street is a major thoroughfare that attracts many potential shoppers from across the globe: locating a retail shop there is desirable because of the big potential market. Assuming that you’re the first person to think of this idea, where would you put the first retail store?

Well, if you assume that the throughput of people going up and down this stretch is roughly the same in both directions, the best place to put the first retail store is right in the center, between 55th and 54th. Exactly halfway (given a little geographical latitude for planning constraints) maximizes the share of the people walking from one end to the other.

But where would a rival firm position a competing retailer, the second in this road? The answer is directly opposite you. To see why, consider if the rival built it somewhere else, such as halfway between 60th and 55th. It would capture customers towards the one end, but you’d be getting 75 percent of customers because yours is closer to more of the strolling shoppers. Therefore, a rival will situate its offering as near to yours as possible — and successive openings will continue to open as near to this cluster until the center is “mined out.” Then, and only then, will entrants open between the middle and end.

Economists use the term imperfect competition to describe market structures with a few competitors, as in oligopoly, or two competitors (duopoly).

Economists use the term imperfect competition to describe market structures with a few competitors, as in oligopoly, or two competitors (duopoly). The important difference between the model of an oligopoly and the model of a perfectly competitive market is that firms in oligopoly can influence market outcomes. As a result, firms behave strategically and try to anticipate the strategic interactions among each other. This means that they form beliefs about what their rivals might do in response to their acts. This behavior makes oligopoly a useful jumping-off point for looking at even more complex markets, and for understanding how the concepts of game theory are relevant to microeconomics. (

The important difference between the model of an oligopoly and the model of a perfectly competitive market is that firms in oligopoly can influence market outcomes. As a result, firms behave strategically and try to anticipate the strategic interactions among each other. This means that they form beliefs about what their rivals might do in response to their acts. This behavior makes oligopoly a useful jumping-off point for looking at even more complex markets, and for understanding how the concepts of game theory are relevant to microeconomics. ( One of the most important of these conditions is that entry and exit is no longer costless. Oligopoly often comes about as a result of the existence of barriers to entry. In a perfectly competitive market, entry and exit are assumed to be costless (see

One of the most important of these conditions is that entry and exit is no longer costless. Oligopoly often comes about as a result of the existence of barriers to entry. In a perfectly competitive market, entry and exit are assumed to be costless (see  In reality, competition among firms is often not as cut-and-dried as these models make out. An offer of a lower price isn’t always a signal that the industry is about to enter into a frenzy of Bertrand competition. Take, for instance, “lowest price guarantees,” which are frequently advertised at big retailers such as Best Buy and Walmart. Far from being a signal that a company is willing to beat the best price in the market, the strategy can be used as a price-cutting deterrence strategy. If you offer to beat anyone else’s price, it actually removes the incentive for anyone else to try and undercut you.

In reality, competition among firms is often not as cut-and-dried as these models make out. An offer of a lower price isn’t always a signal that the industry is about to enter into a frenzy of Bertrand competition. Take, for instance, “lowest price guarantees,” which are frequently advertised at big retailers such as Best Buy and Walmart. Far from being a signal that a company is willing to beat the best price in the market, the strategy can be used as a price-cutting deterrence strategy. If you offer to beat anyone else’s price, it actually removes the incentive for anyone else to try and undercut you.