An Overview: Multicultural Behavior and Global Business Environments

Multiculturalism is a synergistic social chain which integrates all human synergies.

When you have read this chapter you should be able to:

develop conceptual skills to integrate all types of human behavior,

indicate why managing people from diverse cultures is an essential task,

understand the increased role of the level of organizational productivity through cultural synergy,

develop a framework of analysis to enable a student to discuss how to manage multinational organizations,

develop an understanding of the scope of multinational businesses and how they differ from domestic enterprises, and

develop an ability to analyze and evaluate qualitative cultural value systems for multinational corporations.

This chapter illuminates the evolutionary perspectives of multicultural management systems. It bears in mind that international management practices reflect the societies within which business organizations exist. Moreover, technological innovations, societal movements, political events, and economic forces have changed over time and are continuing to change human behavior. In today’s increasingly competitive and demanding international free market economy, managers cannot succeed on their understanding of domestic culture alone. They also need good multicultural interactive skills. This text was written to help both domestic and multinational managers develop people skills in this area.

In our contemporary marketplace, multiculturalism can have a profound impact on human lives. For example, some researchers project that in ten years, ethnic minorities will make up 25 percent of the population in the United States. Copeland (1988: 52) asserts that, “Two-thirds of all global migration is into the United States, but this country is no longer a ‘melting pot’ where newcomers are eager to shed their own cultural heritages and become a homogenized American.” In the United States in the 1990s, roughly 45 percent of all net additions to the labor force were non-European descendants (half of them were first generation immigrants, mostly from Asian and Latin countries) and almost two-thirds were female (Cox, 1993: 1). These trends go beyond the United States. For example, 5 percent of the population of the Netherlands (de Vries, 1992) and 8 to 10 percent of the population in France are ethnic minorities (Horwitz and Foreman, 1990). Moreover, the increase in representation of women in the workforce in the next decade will be greater in much of Europe—and in many of the developing nations—than it will be in the United States (Johnston, 1991: 115). Also, the workforce in many nations of the world is becoming increasingly more diverse along such dimensions as gender, race, and ethnicity (Johnson and O’Mara, 1992: 45; Fullerton, 1987: 19). For example, Miami-based Burger King Corporation recruits and hires many immigrants because newcomers to the United States often like to work in fast-food restaurants and retail operations for the following reasons:

flexible work hours (often around the clock) allow people to hold two jobs or go to school,

entry-level positions require little skill, and

high turnover allows individuals who have initiative and ambition to be promoted rapidly (Solomon, 1993: 58).

In a multicultural society such as the United States, businesses thrive by finding common ground across cultural and ethnic groups. But in more homogeneous cultures such as European and/or Asian countries, businesses are maintaining their local value systems. Although the concepts and principles of management in all cultures may be the same, the practice of management is different.

Hofstede (1993: 83) invited readers to take a trip around the world. He indicates that about two-thirds of German workers hold a Facharbeiterbrief (apprenticeship certificate), and German workers must be trained under foremen’s supervision. In Germany, a higher education diploma is not sufficient for entry-level occupations. In comparison, two-thirds of the workers in Britain have no occupational qualification at all. However, these workers hold formal education certificates to some degree.

American businesses are constantly changing—their images, headquarters, products, services, and the way they do things. To Americans, change is good; change is improvement. However, European cultures and companies will not easily discard their long and proud histories. Europeans believe that patience and an established way of doing things are virtues, not weaknesses (Hill and Dulek, 1993: 51–52). Accordingly, Americans believe that businesses that try to target different demographic groups separately will be stunted by prohibitive marketing costs. Others will meet this challenge through the use of a multicultural consumer mix (Riche, 1991: 34).

From another perspective, in 1992, the European Union (EU) removed all tariffs, capital fund barriers, and people movement barriers from among its member nations. It has created a potential trading block in the industrialized world including at least 327 million people with many different cultures and languages (Fernandez, 1991: 71).

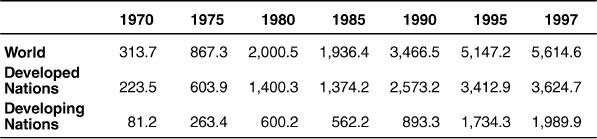

In 1997, the total monetary value of all worldwide exports was recorded in the International Financial Statistics by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as $US5,469.5 billion (see Table 1.1). Out of that sum, the developed nations exported $US3,628.1 billion and the developing nations exported $US 1,841.4 billion. In the same year (1997), the developed nations imported $US3,624.7 billion and the developing nations imported $US 1,989.9 billion (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.1. Total Exports (in Billion $US)

Source: International Finance Statistics. International Monetary Fund (1998). Ll(2), February. Washington, DC.

Table 1.2. Total Imports (in Billion $US)

Source: International Financial Statistics. International Monetary Fund (1998). Ll(2), February. Washington, DC.

By looking at Table 1.3, we may find that the total balance of payments (BOP) of the world, developed nations and developing nations, is not consistent with the balanced trends of imports and exports. This fact indicates that most nations are more dependent on imports than exports. Consequently, they have been faced with trade deficits. The term affordability in the international economy refers not simply to the raw materials and components and the abilities of production capabilities of nations, but also to the solvency of the debtors paying for their debts and compounded interest. In third world countries (TWCs), solvency refers to the acquisition of cash or monetary resources by exploring or trading off more valuable goods. Solvency would also mean that the country is able to appreciate burdens of individual citizens’ educational, health, and welfare deficiencies, nation-states’ weaknesses, and national-international trade transactional deficits (Parhizgar, 1994: 109).

Table 1.3. Total Balance of Payments (BOP) (in Billion $US)

Source: International Financial Statistics. International Monetary Fund (1998). Ll(2), February. Washington, DC.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) among the United States, Canada, and Mexico has created another trading potential, some $212.5 billion annually, a base which should increase considerably (Gordon, 1993: 6). The Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) is another organized intercontinental trading agreement among Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand that was formed to promote cooperation in many areas, including industry and trade. These and other intercontinental trade cooperatives have changed the competitive international marketplace drastically.

In the area of international business, no perceptual approach pays as much explicit attention to the conceptual bases of thoughts and normative actions as multicultural evolution. We are witnessing the emergence of multicultural alliances that rightly could be called global. This indicates that nations are closer to each other, and they need to establish a synergistic strategy to integrate the needs of all nations. As the United States manifested domestic growth, the incentive also increased for companies to move branches of operation outside the home country in the form of strategic business subsidiaries (SBS). By the mid-1990s, companies based in the United States had nearly 20,000 affiliates around the world (Jackson, Miller, and Miller, 1997: 173). In addition, today more than 37,000 companies worldwide have foreign direct investments (FDI) that encompass every type of business function—extracting raw materials from the earth, growing crops, manufacturing products or components, selling outputs, rendering various commercial services, and so on. The 1992 value of these investments was about $2 trillion. The sales from investments were about $5.5 trillion, considerably greater than the $4 trillion value of the world’s exports of products and services (World Investment Report, 1993: 1–4). Considering the scope and magnitude of such international operations, the demand for multicultural understanding for more effective international transactions is high.

The emergence of multicultural communication began to take place as multinational corporations made a shift in their perspectives from solely domestic maximization of profitability to joint optimization of internationalization of individuals and organizational performances. Still, some political thinkers and business owners are generally prone to highlight the alienating influence of multiculturalism on their workplace. Marquardt and Engel (1993: 59) report that: “Based on the number of unsuccessful adjustments and early returns of American business expatriates, both government and private studies agree that more than 30 percent of U.S. corporate overseas assignments fail.” Some corporate managers typically believe that for synergization of their corporation’s wealth and maximization of their profits, it would necessitate that institutions exploit consumers and/or sacrifice workers. However, the modern philosophy of multiculturalism rejects this view of either/or reasoning and envisions that under reciprocal justness, corporate workers’ and consumers’ satisfaction can synergize the corporate wealth and elevate their level of profitability. This belief is anchored in multicultural assumptions about all workers and organizations that power sharing and democratic processes facilitate corporate survival toward more profitability.

There are rational reasons why multinational corporations should make an effort to synergize multiculturalism in their organizations. One of the most important views is the fact that policies concerning the workplace and marketplace affect the quality of lifestyles, the economic well-being of working populations, the social status of employees, and the synergy of technological innovations.

However, corporate managers must recognize that corporate opportunities are limited. They must also recognize that we do not live in an international meritocractic environment and that multinational corporate bureaucracies are partially political. Operating in a competitive free market economy will not allow one to escape these realities. Corporate managers and workers of the multinational corporations must truly understand and interact effectively with people from other cultures. They must understand both home and host countries’ formal and informal values, rules, structures, norms, and attitudes of people and the real cultural criteria for solving social issues. For example, a multinational corporation operating in India must recognize the traditional priorities of social castes of that country in terms of appointing a manager, e.g., a person from a lower caste should not supervise employees from the higher castes.

Status-determining criteria generally have quite different meanings in regard to time, place, and conditions from culture to culture. In some gerontocratic cultures, the older persons are, the higher their status (e.g., France, Germany, Saudi Arabia, China, Russia, and many other countries). However, in a meritocractic culture, once a person reaches a certain age, the status goes downhill.

Historical Transitions in International Business

As Western society shifted from an agricultural to an industrial-based economy in the eighteenth century, scientists and scholars began to realize that traditional cultural philosophies were not effective enough to be useful for Western society. In 1776, Adam Smith proposed the notion of national productivity as the determinant of national wealth. Smith reasoned that nations should export those goods that they could produce at a lower cost than others (absolute advantage theory) and suggested that this labor-productivity advantage could be determined by the percentage of population at work and the “skill, dexterity, and judgment by which labor is generally applied,” (Smith, 1776). In 1933, Bertil Ohlin, following the pioneer work of his teacher, Eli Heckscher (1919), provided an approach which both (a) incorporated more than one kind of input and (b) purported to account for the conditions necessary for trade (Allen, 1967: 27).

Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin presented a new theory based on the work of Smith and David Ricardo. They presented the comparative advantage theory, which argues that all nations have access to the same technology but other factors determine their economic success. Natural resources, capital, land, and the quality of the labor force are among these factors. The main focus of the theory of comparative advantage is to exploit one’s advantages and exchange goods with those that have different advantages. The idea that each nation should exploit what it had and trade for what it lacked made sense with the traditional theories of international trade. These theories were not congruent with a great deal of what already existed in the contemporary international marketplace. Today, there is an entirely new paradigm for multinational corporations based on global markets and invisible national borders. Multinational corporations that understand the paradigm and exploit it will succeed; the others will fail.

Today, the traditional competitive efforts for “resources exploitation” has been shifted to “resources discoveries” for finding productive labor and effective materials. This new method has resulted in the exploration of innovative knowledge and technologies. Such a synergistic integrative effort holds that technological operations need to build a mighty exporting smart machine. If we look back at the beginning of the twentieth century, some 150 years after the beginning of the industrial revolution and thirty-five years after the beginning of the industrialization of the United States, we find that businesses began to ponder more on international transactions.

Industrialization of a nation has always been viewed as a sign of economic growth and development. Multinational corporations engage in international business for three primary reasons: (1) to expand their sales, (2) to acquire resources, and (3) to diversify their sources of sales and supplies (Daniels and Radebaugh, 1994: 9). However, despite these facts, according to Porter (1990: 507–508), “Beginning in the late 1960s, broad segments of American industry began to lose competitive advantage. America’s balance in merchandise trade went into deficits for the first time in the 20th century, in 1971. Trade problems widened even though the dollar fell in the late 1970s.”

In the 1970s, most multinational corporations realized that a major factor in whether a corporation is profitable or not was its multicultural management strategies. Of course, not all domestic and/or multinational corporations manage multiculturalism the same way, but when these relations become well managed, these multinational corporations may have had considerable profit advantages.

The decade of 1970s is an important era in international economy. Competition in the international market caused a new battleground to emerge for multinational rivalry. In 1971, developed nations paid about $2 a barrel for petroleum produced by the thirteen-member Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). By 1981, the price had jumped to an average of $35 to $36 a barrel. The increase had a dramatic impact on developed nations, which were dependent on foreign oil—both in the industrialized West and in the third world. With the transfer of wealth to the exporting oil countries, a dramatic economic shift in power occurred. Not only did the major oil-producing states control a vital resource without which all Western economies would face collapse, they also had accumulation, by the end of 1980, of some $300 billion in foreign assets (Bruzonsky, 1977).

In 1980, the trade surplus of oil-exporting nations reached $152.5 billion (compared with $82.6 billion in 1974). During that year, industrial nations and non-oil exporting developing nations suffered record deficits in their trade balances of $125.3 billion and $102 billion, respectively. Those figures represented a 50 percent increase over 1979, in both the oil-exporting countries’ surpluses and the industrial nations’ deficits (Wormser, 1981: 82).

In the 1980s, competitive strategic planning and organizational structural design in international business became the major concerns of top management of multinational corporations. Businesses in that decade were faced with heavy competition in efficient operational and logistical systems in order to maintain a reasonable level of sales and profits. For example, the abundant inflows of financial resources to the developing countries, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lybia, and Iraq came to an end in 1982. The falling oil price shocked several economies that had become dependent on its continued rise, thus setting off the debt crisis. One of the consequences was the decrease in net capital flows to most developing countries. From a net creditor position of $141 billion at the beginning of 1982, the United States shifted to debtor status and by the end of 1986 owed $264 billion (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1989).

In the same decade, the corporate pretax returns on manufacturing assets averaged 12 percent in 1968 and had fallen to 7 percent (Jackson and O’Dell, 1988: 8–9). In 1960, foreign investors received only 20 percent of U.S. patents and by 1989, received nearly 50 percent (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1989). By the same token, many developing countries, burdened by internal debt, found themselves in economic difficulties and several multinational institutions became more fearful of defaults. The main source of the decrease in capital flows to the developing world came from the private sector. As a result of the debt crisis, increased private flows went primarily to meet the debt servicing needs of debtor countries and little additional capital was available for investment and sustained growth (World Bank, 1991:25).

The persistence of the debt crisis in the early 1980s caused the debtor countries to experience a reversal in resource transfer, lower investment and growth, and higher inflation. The severely indebted middle-income economies experienced an average growth of 2.3 percent from 1973 to 1980 and 2.1 percent for the period 1980 to 1990 (World Bank, 1991: 25). The average annual percentage growth of debt of severely indebted middle-income economies declined from 25.2 percent for the period 1973 to 1980 to 16.2 percent for the period 1980 to 1990 (Parhizgar and Jesswein, 1995:463–473).

The deep international economic recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s was coupled with high inflation and an increase in the values of hard currencies in the international market. Demand and prices for high-technology and other manufactured imports by developing nations increased sharply. Developing nations thus had to borrow heavily to finance their resultant trade deficits. These and other sociopolitical and economic factors have led to the inability of developing nations to offset their newly expanded indebtedness; however, this has also resulted in economic hardships for both lending and borrowing countries.

Today, it would be difficult to find a company that is not affected by global competitive events because most companies secure supplies and resources from foreign countries and/or sell their outputs as finished and/or refined products and/or services abroad. Almost everything that appears within the marketplace and/or market space is competitive in nature. For example, almost 80 percent of all commercial jetliners sold through 1985, in the non-Communist world, were U.S. made. By far, passenger jets had been the biggest export for the United States. In 1987 alone, the jetliner industry added $12 billion to the U.S. trade balance. To be a competitive jetliner company, a company needs a half-dozen models, and it can cost up to $5 billion just to design each one, through heavy investment in research and development (R&D).

In the late 1980s, the competitive challenge came from Europe—as a continental synergistic force. Five European nations developed a pool of resources to compete with U.S. jetliner companies. The European manufacturing consortium was dubbed Airbus Industries. Its planes have wings from Britain, cockpit sections from France, tails from Spain, edge flaps from Belgium, and bodies from Germany. By 1985, Airbus had garnered 11 percent of the world market. By 1988, its sales reached 23 percent of the international jetliner industry (Magaziner and Patinkin, 1990: 231). In the early 1990s, the Airbus Industry caused Boeing and McDonnell Douglas to merge in order to compete with European competitors.

Kolberg and Smith (1992: 17) indicate: “The New Global Commerce System (NGCS) is one in which possession of natural resources, capital, technology, and information are less important to achieving success in international trade. Consider these examples: Mitsubishi automobiles that were designed in Japan are assembled in Thailand and now being sold in the United States under the Plymouth trademark, and GE microwave ovens are sold in the United States after being designed and assembled in South Korea by Samsung.”

The Changing Profile of Global Business Behavior

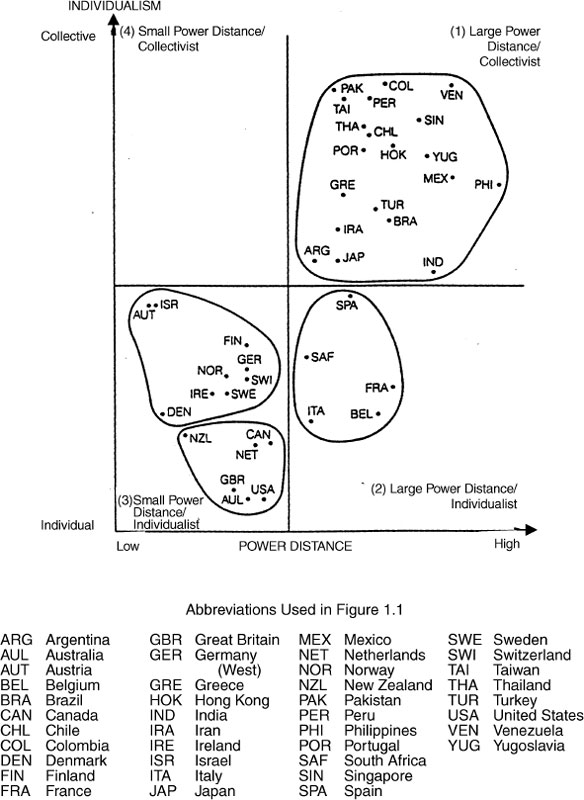

Anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists, and economists have documented the fact that people in different cultures, as well as people within a specific culture, hold divergent value systems on particular issues. Bass and colleagues (1979) studied the attitudes and behaviors of corporate executives in twelve nations and found that our world is becoming more pluralistic and interdependent. Laurent (1983: 75–96) found in his research some differences across national boundaries on the nature of the managerial role. Hofstede (1980a) corroborated and elaborated on Laurent’s and others’ research results in a forty-country study (see Figure 1.1), which was later expanded to include over sixty countries (Hofstede, 1980b); 160,000 employees from U.S. multinational corporations were surveyed twice. Hofstede, like Laurent, found highly significant differences in the behavior and attitudes of employees and managers from different countries who worked within multinational corporations. Also, Hofstede (1980a: 42–63) found that national culture explained more of the differences in work-related values and attitudes than did employee position within the organization, profession, age, or gender.

Figure 1.1. The Position of Forty Countries on Power Distance and Individualism

Source: Geert Hofstede. (1980b). “Motivation, Leadership, and Organization: Do American Theories Apply Abroad?” Organizational Dynamics (Summer), p. 50.

Eitman and Stonehill (1979: 1–2) state that in the world today:

Capital raised in London in the Eurodollar market by a Belgium-based corporation may finance the acquisition of machinery by a subsidiary located in Australia. A management team from French Renault may take over an American-built automotive complex in the Argentine. Clothing for dolls, sewn in Korea on Japanese supplied sewing machines according to U.S. specifications, may be shipped to Northern Mexico (Maquiladora plants) for assembly with other components into dolls being manufactured by a U.S. firm for sale in New York and London during Christmas season. A California manufactured air bus … is powered by British … engines, while a competing air bus … flies on Canadian wing assemblies. A Frenchman is appointed president of the U.S. domiciled IBM World Trade Corporation, while an American establishes … a Swiss-based international fund.

The Nature of International Business

In the late twentieth century, within the heavily competitive international free market economy, some industries reached the maturity of their markets and, in some instances, were faced with the saturation of their domestic markets. Because of this situation, product life cycles (PLC) have become shorter and technological changes are accelerating.

When a corporation reaches market saturation, business performance begins to decline. Such a move can cause international organizations to move toward conglomerate diversification. In conglomerate diversification, timing is important; early entry seems to be a key to success when established companies move into a younger industry (Smith and Cooper, 1988:111–121).

Conglomerate diversification through acquisitions and mergers can lead established international corporations to move into attractive industries without losing their market share and/or product positions. U.S. Steel (now called USX), for example, began its slow movement into the still reasonably attractive petroleum industry with its purchase of Marathon Oil (Wheelen and Hunger, 1995: 158). However, technological change, rapid product life cycles, quality control, organizational learning, managing multicultural synergy, and innovation are primary issues for multinational organizations in the new century. Managing multicultural behavior is the key to effective management of all areas of today’s international free market economy.

International Business Environments

International businesses do not exist in a vacuum. They arise out of necessity for home and host countries. The host countries are in need for particular products or services and the home country is in need of market expansion, product diversification, increased sales and profits, low cost operation, and exploiting growth opportunities. As a result, international businesses must constantly be aware of the key variables in their environments. Some factors are very important in understanding the nature of the different kinds of international business entities. These factors are ownership, investment, management and controlling systems, marketing segmentation, subsidiaries’ autonomy, and consumers’ lifestyles. For the clarity of the terms used in this text, the following are brief definitions of international business entities (Parhizgar, 1999: 1–25).

Global Corporations

A global corporation is a business entity which obtains the factors of production from all countries without restriction and/or discrimination against by both home and host countries. It markets its products and/or services around the globe for the purpose of profits (e.g., The World Bank Group and The International Finance Corporation [IFC]). These organizations around the globe serve their investors, managers, employees, and consumers regardless of their sociopolitical and economic differences.

Multinational Corporations

A multinational corporation (MNC) is a highly developed organization with extensive worldwide involvement; it obtains the factors of production from multiple countries around the world. An MNC manufactures its products and markets them in specific international markets (e.g., Exxon in energy; General Motors in automobiles; Mitsui and Co., Ltd. in wholesale; IBM in computers; E.I. du Pont de Nemours in chemicals; and General Electric in electrical equipment).

International Corporations

An international corporation (IC) is a domestic entity which operates its production activities in full scale at home and markets its products and/or services beyond its national geographic and/or political borders. In return, it imports the value-added monetary incomes to its country. It engages in exporting goods, services, and management.

Foreign Corporations

A foreign corporation (FC) is a business entity whose assets have been invested by a group of foreigners to operate its production system and markets its products and/or services in host countries for the purpose of making profits. These corporations are controlled and managed by foreigners to the extent that they adhere to all rules and regulations of the host countries (e.g., Japanese Sanwa Bank Limited in the United States).

Transnational Corporations

A transnational corporation (TNC) refers to an organization whose management and ownership are divided equally among two or more nations. These corporations acquire their factors of production around the world and market them in specific countries (e.g., Royal Dutch/Shell Group whose headquarters are located in the Netherlands and United Kingdom). This term is most commonly used by European countries.

Supernational Corporations

The supernational corporations (SNCs) are small domestic corporations which create large market shares and product positions in the regional markets. Specifically, SNCs are emerging from e-commerce. SNCs are heavily dependent on logistics and transportation services: sea, air, and land.

Maquiladora Corporations

The maquiladora companies are known as the “twin plants,” “production sharing,” or “inbound organizations” which allow for duty-free importation of machinery, raw materials, and the components of “inbound” production. Maquila is derived from the Spanish verb maquilar, which translates as “to do work for another.” The current usage describes Mexican corporations that are being paid a fee for processing materials for foreign corporations. Maquilas are assembly plant operations in Mexico under special customs arrangement and foreign investment regulations whereby they import dutyfree materials into Mexico, on a temporary basis, and export finished goods from Mexico. These plants pay only a value-added tax on exports. The number of maquiladoras has increased significantly from 12 plants in 1965 to 2,400 in 1997, employing over 740,000 Mexican workers (Parhizgar and Landeck, 1997: 427).

The Field of Multicultural Behavior

Although multiculturalism is increasingly accepted as a focal subject of academic inquiry, many researchers conclude that multinational corporations need to pay more attention to this issue. Some corporate officers and politicians still debate whether multiculturalism should be practiced. These groups are more attuned to cultural diversity than to multiculturalism. These two terms (muliculturalism and cultural diversity) are the major issues on which this text focuses in order to clarify their meanings and applications in the field of international business.

Multiculturalism, similar to snapshots of a culture, can be taken from different angles and distances. Snapshots occur at different times within the context of multinational organizations. There is no comprehensive systemized formula to categorize human civilizations. No single multicultural picture or perspective as a multinational corporation can depict the multifaceted characteristics of human behavior, because diversified value systems differ in focus and scope of ethics, morality, and legality (Harvey and Mallard, 1995: 3).

No phenomenon has fascinated researchers in the modern globalized and free market economy more than multicultural moral and ethical value systems. In recent years, multinational management perceptions have been shaken. Much public concern has surfaced over these issues. One belief is that the value systems of humanity that made the late twentieth century’s accomplishments so achievable are the result of global competitive cooperation. For example, American culture, which represents multiculturalism, emphasizes the importance of cooperation between workers and capital holders for more synergy. Some researchers concluded that there is widespread ethical commitment among U.S. workers to improve productivity (Yankelovich, 1982: 5–8). With such a breadth of American cultural perception, what causes both employers and employees to strive for productivity? Do employees view work as a necessity to continue their lives? Are people’s views on work a binding contract between employee and employer? Or do U.S. workers view work as an achievement toward higher levels of profitability? The answer to all these questions indicates that the more money a corporation earns, the harder they work; the more profit they make, the higher the wages and benefits that are paid to workers.

Profitability is a social contract between workers and capital holders; it is also a legitimate agreement between society and organizations, whose mandate and limits are set by ethical, moral, and legal systems. Its limits are often moral, but they are also frequently written into law. Similar to the early days of American enterprises, the Protestant work ethic was a strong influence, providing both motivation and justification for a businessperson’s activities. According to such an ethical value system, the good and hardworking people were blessed with riches; the lazy and incompetent ones suffered (De George, 1995: 14).

The work ethics in multinational corporations have different dimensions. In some cultures, for example, ethics and morality have conceptual, technological, and legal aspects, while in others, they have social, ethical, and moral implications. The conceptual dimension consists of choosing from architectural scientific alternatives in designing and planning the operational processes of a business. The technological dimension consists of developing methods of embodying the new engineering and operational systems for producing new profitable products and processes. The legal aspect consists of discipline and order to govern the rightful use of wealth and power. In such cultures, workers’ perceptions are essentially rational. Even in these cultures, workers believe that Mother Nature follows the law of rational thought. Existentialists believe that thoughts and practicality coexist without overlapping. However, in other cultures, thoughts and rationality coexist in a dialectic reasoning and the results would be a synthesized conclusion in societal practicality.

However, Kirrane (1990: 53) indicates that, “The very term, ‘business ethics,’ tends to arouse some people’s cynicism. They shake their heads and woefully recite recent scandals.” Contrary to the belief that cultural and ethical value systems are merely business buzzwords, they are often the major predictors of the success or failure in either an industry or a company’s strategy.

Within the globalized business environment, many people agree that some multinational corporations believe their businesses should not be concerned with international philanthropy or with corporate ethics beyond their adherence to international legal requirements. The prominent business advisor Peter Drucker (1980: 190) has written that ethics is a matter for one’s “private soul.” Following his reasoning, he states that management’s job is to make human strength productive. Further, economist Milton Friedman (1970) argues that the doctrine of social responsibility for businesses means acceptance of the socialist view that political mechanisms, rather than market mechanisms, are appropriate ways to allocate resources to alternative uses. However, in globalization of international enterprises, altering people’s cultural and ethical value systems is not the ultimate aim. Managing multicultural value systems among nations is the challenging means to achieve successful globalization.

Many multinational corporations through various statements of beliefs communicate their organizational ethical, cultural, and legal value systems. These value systems have been called credos, missions, or corporate philosophy statements. Johnson & Johnson <http://www.jni.com/who_is_jnj/cr_usa.html> addresses its corporate beliefs about principles of responsibility to: “The doctors, nurses, and patients, to parents and all others who use our products and service … to our employees, the men and women who work with us … to communities in which we live and work and to the world community as well.”

A problem facing many executives, managers, and employees in globalizing corporations, is that few people within organizations comprehend all areas of organizational ethical, cultural, and legal systems in transition. An example is the company Intel, in which senior managers usually concentrated on global strategy and structure. Middle managers complained that various aspects of the corporate culture prohibited them from acting globally. Human resource people focused on building better interpersonal and cross-cultural skills (Rhinesmith, 1991: 24–27).

Understanding corporate cultural, ethical, and legal value systems in a time of conversion from domestic to global market operations, requires transition through several stages. Since members of international, multinational, and globalized organizations can enter with different cultural backgrounds and leave corporations very rapidly, managers try to leave corporate cultural and ethical value systems intact. However, along with the globalization processes of a corporation, many issues remain unresolved. For example, based on the promise that global strategy and structure can increase profits and promote growth, these concepts become the primary responsibilities of corporate managers. However, no consideration is given to cross-cultural relations between producers and consumers.

Today, some business school curricula have been designed to educate future business leaders on the basis of global strategy and structure in order to promote profit and growth. The curricula attempt to separate business operations from host countries’ civic and humanitarian responsibilities. Cross-cultural experts believe that ethics is a system of beliefs that supports morality. Moral value systems involve cognitive standards of understanding by which people are judged right or wrong—especially in relationships with other people. Ethical value systems are also known as functions for making decisions that balance competitive demands.

Organizational behavior researchers have embraced the concept of cultural value systems to study such focal topics as a major commitment (Pascal, 1985), socialization (Schein, 1968), and turnover (O’Reilly, Caldwell, and Barnett, 1989). When a company changes its exporting functions to a global market, most often it establishes manufacturing, distribution channels, marketing, and sales facilities abroad. In such a transitional stage, analyzing the cultural and ethical value systems leads us to question certain commonly held beliefs about a company’s culture. As Harrison and Carroll (1991: 552) indicate: “For instance, very rapid organizational growth sometimes facilitates rather than impedes cultural stability, when stability is viewed as the quickness with which the system reaches equilibrium or rebounds to it after perturbation.”

When a company becomes multinational, it creates miniatures of itself in its host countries. These companies are staffed by other nationals and gain a wide degree of autonomy. In practice, it will often be quite difficult to classify the predominant value systems in a globalized corporation. However, it should be relatively easy to identify the sources of the value systems at home and in the host countries.

Globalization of International Business

In globalization of a multinational corporation, there is a fundamental requirement for definition and classification of most conceptual and practical value systems, which reflects the central elements defining the general producer and consumer rights. Since these values are central to the concepts of cultural, ethical, and legal practices of businesses, the definitions and classification of value systems should be internationally known through the international business practices. Furthermore, focusing on a unified well-defined international value system within the community of nations permits the examination of the likely effects of different types of subvalue systems on both national and corporate value cultures. Focusing on the following three value-based dimensions of cultural, ethical, and legal practices are particularly useful for legitimization of international business operations.

Corporate Paradigm Management Scale

Parhizgar (1995:145) constructed a matrix model as a foundational philosophy for analyzing the application of the corporate paradigm management scale (CPMS) (see Table 1.4). The two-dimensional value-based matrix system helps simplify the analysis of the complex CPMS. Not surprisingly, several of these scales have been applied for analysis of corporate cultural, ethical, and legal value systems. In an international endeavor, the problem is the components of the CPMS matrix have not typically been based on global views. These components do not match with the shared values that form the core concepts of international business. Rather, they have been formulated with a broad range of variables based upon corporate national-origin cultural philosophy.

Table 1.4. Corporate Paradigm Management Scale (CPMS)

Source: Parhizgar, K. D. (1995). “Creating Cultural Paradigm Structures for Globalized Corporate Management Ethics.” In Evans, J. R., Berman, B., and Barak, B. (Eds.), Proceedings: 1995 Research Conference on Ethics and Social Responsibility in Marketinq. Homestead, NY: Frank G. Zarb School of Business, Hofstra University Press, p. 145.

The Focus on Universal Ethical Value Systems

In a global business process, ethics can be a misleading perception because different nations perceive ethical value systems differently. Ethical perception is an individual’s belief about what is right and wrong, good and bad, just and unjust, and fair and unfair. Note that ethical and moral beliefs in a culture are rules or standards governing the quality of behavior of individual members of a profession, group, or society—not a specific organization. U.S. businesses, in the 1970s and 1980s, were full of accounts of poor ethics. Big scandals, such as the Lockheed Company’s bribery, Michael Milken, and Ivan Boesky, became examples of unethical and, in most cases, illegal practices of doing business in the United States and abroad (Stewart, 1991; Arenson, 1986).

For example, on September 30, 1982, seven people in the Chicago area died from cyanide introduced into their Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules. The Tylenol in question was found to have been laced with cyanide, and it was not known for several weeks whether the contamination was the result of internal or external sabotage. The Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Company, the manufacturer of pain reliever, Tylenol, did not know whether the cyanide had been introduced into the Tylenol bottles during the manufacturing process or at a later time. A thorough investigation proved that the poisonings were the result of external sabotage (Newsweek: 1983: 32). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) immediately issued a warning to the public not to take Tylenol. The company pulled all Tylenol from shelves in the Chicago area. That was quickly followed by a nationwide recall of all Tylenol—31 million bottles with a retail value of over more than $100 million. The loss was not covered by insurance. The company put the safety of the public first, as the company’s credo says it should do (Foster, 1983: 2). The mission of the Johnson & Johnson credo, as we reported earlier in this chapter, states: “We believe our first responsibility is to the doctors, nurses, and patients, to mothers, and all others who use our products and services.” Johnson & Johnson’s chief executive officer (CEO), James Burke, was a marketing man who knew and understood the value of customers. Not many CEOs are comfortable with open communications in the time of a crisis, and their natural reticence can be enormously harmful to their organization when a crisis strikes (Donaldson and Werhane, 1988: 414).

By using unscrupulous means, executive managers may concede the highest value for their business operations. They need to accept corporate responsibilities by giving weight to the ethical issues concerning the well-being of operations of their companies. Nevertheless, the priority in pursuing the public safety is the highest ethical virtue of the means and ends of a corporation. The major implication in global business is that people with different beliefs will have different ethical standards. Therefore, ethical considerations are relative; they are not absolute standards of human thoughts and behaviors for all people. Ethical behavior and conduct in global business transactions depend upon the belief systems of producers and consumers. Whether the behavior of a person is ethical depends on whom the focus is upon and who is judging. There is no single best way to ensure that a corporate manager can make ethical decisions. Written codes of conduct often look great, but they may have no effect if employees do not believe or feel that top management takes the codes of ethics seriously.

Ethical considerations are just some of the multitude of factors that influence decision making in organizations. A company lives or dies by its ethical decisions and actions over a long period of time. The difficulty of understanding global business ethics is what worries people the most because they do not know what they are getting into. Are they making the right decisions? Will they get into further trouble? By understanding corporate ethical value systems, worries will be relieved because employees will know that they are making the right decisions boldly and confidently.

In the past, many portfolio investors chose to be passive instead of active stockholders. Investors are beginning to pressure corporations with tactics such as media exposure and government attention. Some have formed a class of corporate owners called shareholder activists. These people pressure corporate managers to boost profits and dividends. For example, in the 1990s, a number of CEOs from major multinational corporations—IBM, General Motors, Apple, and Eastman Kodak, to name a few—have been expelled by dissatisfied stockholders (Fabrikant, 1995, p. 9). Now that the markets are fluctuating, and many investors have their life savings, retirement funds, and other monies invested, people have awakened and realized that they must take an active role in their investments.

Nowadays, international stock market investors are very sensitive to the behaviors of global corporate chief executive officers (CEOs). Officers lose patience when they feel that their jobs are on the line. Therefore, they react with swift action, selling their stockholdings for minimal profit margins rather than letting them mature and then selling them for substantial profits.

The Focus on National Legal Value Systems

The rules for doing business in a global market have changed drastically. Those corporations who understand the new international rules for doing business in a free world economy will prosper; those who cannot may perish (Mohrman and Mitroff, 1987: 37). Like people, rules and regulations have an origin. But the international regulatory process is not widely understood or practiced by nations. Usually, in industrialized societies, the government’s regulatory life cycle first begins with the emergence of an acute issue. Second is the formulation of government policy. Third is the implementation of the legislation. Then, these rules and regulations will be circulated internationally.

Business operations and trade transactions are monitored and, when necessary, informal or formal corrective actions are taken. It is not easy to portray the magnitude of global business and the sheer volume of regulations to which global businesses are subject. International business rules and regulations are very complex. For example, on December 3, 1984, the Union Carbide Pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, faced a problem when a sequence of procedures and devices failed. Escaping lethal vapors crossed the plant boundaries, killing 4,037 people and caused serious injury to 60,000 more people around the plant. The lethal gas leak has been called one of the worst industrial-mass disasters ever, second only to the release of radionuclides by a Russian reactor at Chernobyl in the Ukraine in 1986. The Ukrainian authorities estimated that radiation-related deaths totaled 125,000 and elevated death rates will continue in the next decades because of latency periods for radiation-induced illnesses (Williams, 1995: A4). The catastrophes at Chernobyl, Ukraine, and Bhopal, India, were international manifestations of some fundamentally wrong actions by governments and businesses in modern times (Weir, 1987: xii). Who should and could be blamed for such catastrophes? Were the former Soviet Union and Indian governments at fault? Was the Bhopal incident the Union Carbide Company’s fault? Or was it the United Nations’ World Health Organization (WHO) and/or the United Nations Atomic Energy Commissioner’s deficiency?

The Focus on Corporate Multicultural Value Systems

The primary focus of a global corporation is based upon cultural values concerning functions performed for and in relation to international organizations and government representatives, as well as consumers. In a cultural value system, either universal or regional, the major concern is focusing on the contexts of issues (Swierczek, 1988: 76). Managerial and organizational cultures are concerned with the particular environmental conditions or sets of problems in which skills, techniques, and approaches are applied. The key questions about managerial and organizational cultures could be raised as: “Are these applications appropriately designed considering circumstances or fixed-value systems?” and “Is the managerial and organizational framework of cultural value systems consistent with the framework of value systems in the situation in which the applications are made?” These and other questions raise several issues about the legitimacy of a national cultural value system within the context of the international environment. If management culture is universal, then the transfer of techniques will be culturally compatible. If management culture is a national phenomenon, companies must make greater efforts to transform these approaches during the globalization process regardless of their cultural heritage or origin of these cultural value systems. For example, consider a manufacturer who wishes to survive in a very intensive competitive market. He or she feels that in order to sell products a potential foreign government authority must be bribed. Is there any similar cultural and/or ethical rule in both home and host countries? In these situations, we must consider the international rule, to bribe and/or to be bribed are not universal practices. If we attempt to universalize the rule involved, we quickly perceive that it is self-contradictory: if bribery has not been made a universal rule, then bribery would not be a universal way of doing business. The main argument is that although managerial culture could be universal, organizational cultures could be different. In order for a universal management culture to be effective, there should be similarities in the organizational cultural value systems with the universal managerial value systems. Then the end result in a managerial culture becomes universal.

Global strategy and structure are important, but the heart of a global organization is its corporate culture. It is the means through which global strategies and structures are executed in order to ensure global competitiveness and profitability. A global corporate culture comprises the mission, vision, values, beliefs, expectations, and both conceptual and perceptual attitudes of its members. Most domestic firms find that their greatest weakness is their difficulty to change their corporate cultural value systems to compete in globalized markets. It is becoming clear to researchers that Japanese and European corporate cultures and management practices put much greater effort over a much longer period of time into developing global corporate cultures and human resources than do U.S. companies (Rhinesmith, 1991: 131–137). For example, the corporate cultural value systems of the Japanese are very different from those of the United States. Eccles (1991: 131–137) indicates that during the 1980s many executives saw their companies’ success decline because global competitors seized their market shares.

In order to succeed as a profit-making organization, multinational corporations must move toward a task-alignment form, which means reengineering the organizational task force and employees’ roles, reinventing corporate responsibilities, and reenergizing corporate relations with customers to solve specific global business problems (Beer, Eisenstat, and Spector, 1990: 158–166). Therefore, to be an effective global corporation, top management must strive toward changing the cultural, ethical, and legal attitudes of all stakeholders within their organizational context. Employees must be informed of the problems affecting the organization and dragging it into a profitless market environment. Since an organization consists of hundreds of individuals and different departments, both employees and employers are required to enforce organizational cultural, ethical, and legal value systems. In sum, the corporate management discipline system should eliminate improper occurrences of unethical and illegal conducts and promptly provide suitable alternatives in order to match their legitimized corporate mission. However, employees must recognize that in almost all cases of difficulties, they are part of the problem and a great deal of the solution. Employers and employees in a competitive global marketplace and market space must understand who they really are. Therefore, multinational corporations should strive to discover their strengths and weaknesses and then try to convert weaknesses to strengths.

Multiculturalism and Cultural Diversity

For the clarity of the distinctive concepts and practices of cultural management, generally, there are two major sociopolitical and economic perspectives among nations which are operating in the field of international business: (1) multiculturalism and (2) cultural diversity.

Definition of Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism is a basic framework through which one views the world as a community of people. The fundamental idea behind multiculturalism is that everyone is individual and that we are more similar than we are different. This notion is based upon a civic ideology that all subcultures within a society encompass all similar values and people from all ethnicities, religious faiths, political ideologies, and traditions should be treated the same. Multiculturalism is color blind, gender blind, race blind, and bias and/or prejudice blind. Multiculturalism does not view diversity issues as hierarchical and/or class issues. Differences among individuals and classes of people are due to individual characteristics, not due to their collectivistic historical and cultural background. Multiculturalism means a healthy environment in which everyone has an appropriate place in that particular society according to his or her personal qualifications. People respect each other regardless of their differences and/or group affiliation. Therefore, multiculturalism is the means of collaborative participation among multiple cultures in one social system to share their mutual understanding for pacing the whole social system toward a meaningful achievement for all. The concepts and perceptions of multicultural management are lively and practical. These features are:

Multiculturalism can create a sense of interdependence, interrelatedness, and above all correlated human synergies. Multicultural synergies seek an effort with combined performances that create greater efforts than the total of the sum of their parts.

Multiculturalism is building a peaceful place for all cultural beliefs and values. It is driving international relations toward civilized synergy—no valuable human thoughts and efforts will be given up or lost.

Multiculturalism is a potential synergy in which the major components of a firm’s product-market strategy are directed toward desired characteristics of the fit between the firm and its substitute product-market entries.

Since multicultural behavioral knowledge is a powerful managerial tool for conducting international business, it is within the described context that it has placed international business as its focal point of interest.

Definition of Cultural Diversity

Cultural diversity means the representation of majority and minority groups in a society according to their historical family wealth and political influence. It makes a distinction among ethnicity, race, color, gender, and wealth. It makes people different, with distinctly different group affiliations of cultural significance. Cultural diversity emphasizes dissimilarities among people; it emphasizes this notion that we are more different than we are similar. The difference between cultural diversity and multiculturalism is the distinction between classes of people according to their original sociopolitical and cultural ideologies. In cultural diversity, there are majority and minority groups, but in multiculturalism there is no stratification of people on the basis of race, color, ethnicity, and nationality. While multiculturalism is pluralistic societal teamwork on the basis of meritocracy, cultural diversity is based upon the original grass roots of cultural bureaucratic characteristics. This means that those majority groups who have had more power and more people deserve to enjoy more privileges. Therefore, multinational organizations should reward their employees on the basis of seniority rather than merit. We will discuss more about these issues in detail in the following chapters.

The introductory chapter discussed exactly what is meant by multicultural behavior and multinational management, and outlined the general perspectives and objectives of this new field. The chapter then turned to brief historical definitions of business transactions and organizational decision-making processes. The ethical, moral, and legal implications of multicultural value systems have been analyzed. All of these observations have vast and profound implications for multinational management and the future of business enterprises. Currently, the management of multinational corporations is significantly different from what the domestic corporate management was before 1990. Everyone should be concerned about multicultural human behavior. The field of multicultural behaviorism has the goals of understanding, prediction, and assimilating individual conceptions into pluralistic ones. Multicultural management provides appropriate room for all organizational members to appreciate their value systems in congruence with other organizational members in an effort toward synergy.

Chapter Questions for Discussion

How does the multicultural organizational management relate to, or differ from, domestic corporate management?

Identify and briefly summarize the major historical transitions of human civilizations.

In your own words, identify and summarize the many variations in multicultural management processes.

How does a multicultural value system synergize organizational productivity?

Identify and explain the viable conceptual reasoning methods in multicultural management.

Learning About Yourself Exercise #1

What Do You Value?

Following are sixteen items. Rate how important each one is to you on a scale of 0 (not important) to 100 (very important). Write the number 0–100 on the line to the left of each item.

_____ |

1. |

A high-paying j ob |

_____ |

2. |

Job security |

_____ |

3. |

A good working environment |

_____ |

4. |

Working with other nationalities |

_____ |

5. |

Working with other ethnicities |

_____ |

6. |

Interest in other religions |

_____ |

7. |

My religion |

_____ |

8. |

A career to work in other countries |

_____ |

9. |

Spending time with my family |

_____ |

10. |

An ethical and moral environment |

_____ |

11. |

Continuing my education |

_____ |

12. |

Working for myself |

_____ |

13. |

To be employed in a government agency |

_____ |

14. |

To work for a foreign corporation |

_____ |

15. |

A commitment to marriage cohesiveness |

_____ |

16. |

Nice cars, comfortable homes, and fashionable clothes |

Turn to the next page for scoring directions and key.

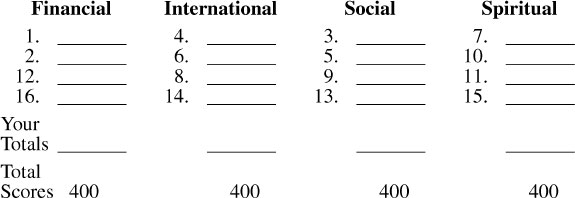

Scoring Directions and Key for Exercise #1

Transfer the numbers for each of the sixteen items to the appropriate column, then add up the four numbers in each column.

The higher the total in any dimension, the more importance you place on that set. The closer the numbers are in four dimensions, the more multi-culturally oriented you are.

Make up a categorical scale of your findings on the basis of more weight for the values of each category.

For example:

1. 400 Spiritual | |

2. 375 Social | |

3. 200 Financial | |

4. 150 International | |

Your Totals |

1,025 |

Total Scores |

1,600 |

After you have tabulated your scores, compare them with others. You will find different value systems among people with diverse scores and preferred mode of perceptions.

International Business Machines (IBM) is a very well-known multinational corporation. IBM headquarters is located in Armonk, just outside of New York City. IBM Argentina is one of its subsidiaries, located in Buenos Aires. IBM has two fundamental missions. First, it strives to lead in the creation, development, and manufacture of technology, including computer systems, software, networking systems, and microelectronics. Second, it translates these advanced technologies into value for its customers worldwide through its sales and professional service units.

IBM has open system centers in thirty-four countries. One of its business goals is to expand its market share and product positions through the client/server computing services. On May 20,1997, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the court indicted ten of IBM Argentina’s managers on charges of bribery in connection with a scandal over a contract between the local subsidiary of IBM Argentina and Banco Nacion, a state-owned bank in Argentina. IBM Argentina was accused of paying $249 million in bribes to Banco Nacion’s authorities in order to computerize 525 branches.

In the United States, the FBI and the Securities and Exchange Commission had also been investigating the bribery case. However, IBM’s corporate headquarter manager denied any wrongdoing.

The Banco Nacion is one of the largest financial institution in Argentina with assets of $11 billion. Under the contract in question, IBM Argentina had reached an agreement with an Argentinian company, Capacitación y Computatión Rural S.A., or C. C. R., to provide back-up software for a main program to connect Banco Nacion’s 525 branches to a computer network. IBM Argentina paid C. C. R. $21 million before auditors from Argentina’s tax agency began asking questions. What concerned the auditors was that IBM (the main office in New York) received nothing in return and that C. C. R. paid out most of $21 million to phantom subcontractors, some of which deposited the money in Swiss bank accounts.

The incidents of this case happened very quickly. Both IBM Argentina and Banco Nacion were found guilty by the Argentina court. One was guilty of offering the bribe and the other for accepting it. However, IBM sued the bank, which canceled its contract with IBM after the scandal surfaced. There are many ways that could help IBM headquarters in New York prevent this embarrassing situation in its subsidiaries around the world.

Since a corporation is a legal entity with legal rights and responsibilities, it must have high moral standards and monitor all its subsidiaries’ operations, because there are limits to what the law can do to ensure that business decisions and operations are socially and morally acceptable. All decisions and operations of a trustworthy multinational corporation require trust and confidence. IBM needs to establish realistic and workable codes of ethics for all its subsidiaries in order to prevent such an embarassing incident.

Source: The New York Times (1997). “10 Indicted Over I.B.M. Contract.” May 21, Section D, p. 12.