The unexamined philosophical understanding who we were, who we are, and who we will be is not worth thinking.

When you have read this chapter you should be able to:

understand fundamental principles of multicultural philosophies,

describe what is meant by a cultural philosophy of a human’s image,

identify the mainstream of key thoughts in perceptual paths of cultural philosophies,

conceptualize the multicultural civilization,

discuss the cultural resources fitness of a culture,

describe the knowledge-based wealth of a civilization, and

identify structural dimensions of cultural philosophy.

Cultural philosophy has been given only cursory treatment in the majority of comparative academic circles that have appeared. If one reviews the research of Hoeble (1960), one finds that culture was defined as the integrated sum total of learned behavioral traits that are manifested and shared by members of a society. Cultural philosophy is an elusive concept, a fuzzy, difficult to define construct (Triandis et al., 1986). Multicultural philosophies can be defined as communicable thoughts, intellectual knowledge, and causal distinctive patterns of human minds which separate accultured from noncultured human beings.

One area of philosophical dispute involves whether culture is inherited or learned. The majority view is summed up by many researchers who believe any given culture or way of life is learned behavior which depends upon the environment and not on heredity. However, human groups lack the genetic programming to survive. Other animals have to ensure they behave in predictable patterns of behaviors that promote their collective survival. Instead, human groups possess an open and conscious perception that permits them to behave in a survival and growth condition. As Hillman and Sonnenberg indicate in Psychology Today (1989: 48), “Sigmund Freud first perceived that problems of human behavior were often subject to cause-and-effect relationships that people were not consciously aware of.” From this view, Freud concluded that unconscious mental processes motivate much of human behavior. He called these processes the id (the unleashed, raw, instinctual drive struggling for gratification and pleasure), the ego (the conscious, logical portion that associates with reality), and the superego (the conscience that provides the norms that enable the ego to determine what is right and what is wrong) (Luthans, 1988). However, Geertz (1963) indicates that we are, in sum, incomplete—and not through culture in general, all human activities are integral parts of our cultural philosophies. Cultural philosophies, like other conscious and deliberate thoughts, seek to create civility of intellectuality.

Cultural Philosophy of the Human Image

Isolating the influence of cultural philosophies on the development of managerial value systems is a perplexing problem for comparative international management researchers (Kelley, Whatley, and Worthley, 1987; Kelley and Worthley, 1981). Differences in viewing the world we live in, the divine we believe in, and the way to proceed it, could be attributable to cultural philosophical meanings. For example, within the boundary of international consumption, the most powerful challenge comes from the “rational” choice. Multinational corporate managers occasionally believe that the importance of cultural differences should be the focal point in decision-making processes and operations. However, they ignore this fact, because implicitly they assume that, in a given consumerable situation, all people make the same “rational” choices regardless of their cultural orientations. In addition, as Inglehart and Carballo (1997: 34) indicate, modernization philosophy focuses on the differences between “traditional” and “modem” societies, each of which is characterized by distinctive economic, political, social, and cultural situations.

The framework in transitional stages of business philosophy to the new evolutionary, regionalized, and multinationalized trade zones (e.g., EU, NAFTA, MERCOSUR, and ASEAN) is based upon the new visions and images of human nature. The new image is viewed as just that—human nature—as if it is something that has always been the same. Such imagery was understood prior to the twentieth century. Within such a traditional image, people used to perceive that conditions of “existence” were much the same with people functioning accordingly. Traditionally, philosophical perceptions of human beings for their existence were focused on how to survive. Analytically, if we were to pick one word which could be descriptive to the conditions of “existence” to the “traditional pattern of perception,” that word would be “harsh.” Under harsh conditions, human beings’ primary objective was simple. It was “proocupation” with survival. However, the dramatic changes brought about by human civilizations have changed such an image. The “harsh” conditions have become “favorable” instead. And human proocupation with survival has become a “preoccupation” with fulfillment and achievement, which can be understood as “growth.”

From the standpoint of faith, the major philosophical view of the religious human idea about existence shifted from a traditional philosophy of “God and Universe” (double natures) to “God, Universe, and Human” (triple natures). From the standpoint of the existentialist, beliefs shifted from “Nature and Universe” (double natures) to “Nature, Life, and Human” (triple natures). Contemporary scientists have found that space has three dimensions: width, depth, and height; accordingly, a human being also possesses these dimensions (Vazsony, 1980). Still, existence and survival are the whole.

Historically, traditional philosophers ignored the potency of human culture, which possesses permanent superiority over two other dimensions, namely existence and survival (Parhizgar, 1988). The most generic image of human culture comes from philosophical information. Information is culturally learned knowledge for the purpose of taking effective actions. Both cultural existence and survival possess their own synergistic potency which cannot be philosophically changed into quantitative reasoning for an assessment. However, both qualitative and quantitative assessments could be misconceived, when they are taken to be antitheoretical and/or even alternative.

For example, most Asian cultural philosophies from Eastern to Western Asian countries—from mainland China to India—do not have differentiated values between the “human” and the “divine.” On one hand, in Asian cultural philosophies, the way of life has been regarded as the way of Dharma, Karma, Samskaras, Nirvana, Kami, Zen, Theravada, and Mahayana— the spirit of Heaven extended into the material universe, and no other way is considered to exist (Mason, 1967). On the other hand, cultural philosophies in the European and American countries have perceived that the universe originated from God as the first and sole cause, the creation of man was the final and most important step in creation, and God created the cosmos out of “waste” or “void,” which existed with God before creation (Weber, 1960). The Illuminationist (Eshragh) Persian philosopher, Suhrewardi (1186) asserts that reality is divided into four phenomena: (1) pure light (Nur-e-Mojarrad), (2) substantial (Zaroorat), (3) accidental (Hadeseh), and (4) darkness (Zolmat). The first phenomenon is the origin of God. The pure unity of the nature of the highest reality is the Light of Lights, God. It is purely immaterial and immortal. From this One Light, another light emanates which is called existence. That is the substantial light, which is immaterial light and is prior to others. The third of these lights emanates both other lights and darkness which is called the universe. The universe has both accidental darkness in lights and substantial darkness—the “dark barriers.” These lights differ in intensity and in accidents. The fourth light, through very complex interactions among lights on different levels, emanates both a vertical order of lights—the intellects corresponding to the spheres of planets—and a horizontal order—lights of equal intensity differing by their accidents. This horizontal order of lights is what in Greek philosophy Plato refers to as the Forms and what then in Persian philosophy is called angeles. It is through their solicitude that the earthly kinds of life and species are maintained (Suhrewardi, 1186).

Although all nations possess distinctive cultural philosophies and valuable patterns of ideologies, it would be a mistake to think that any particular nation has a single binding culture. Social scientists have observed that all human groups have multiple cultural perceptions in different societies at different times. For example, do coherent cultural values and patterns of behavior exist among these people? Converse (1963) illustrated that the belief systems of mass publics do not show much constraint: mass attitudes toward various issues are only weakly related to each other. Knowing a given individual’s belief in one way of life does not enable us to predict their position on other issues. However, in the field of international business, cultural philosophy makes huge differences between the basic universal values of peoples in different cultural groups. I find that this is true because producers’ and consumers’ perceptions in a given economic and technological environment tend to go together. They do so because they are mutually supporting the notion of development and growth.

Human beings are social creatures that progress through heredity, environment, maturation, and learning. Mischel (1971: 227) states that: “Socialization is not a haphazard accumulation of bits of behavior but entails, instead, some orderly development. That is true at least to the degree that some complex social behavior patterns are sequential.”

The human mind is by nature and structure cross-cultural. It is the mind that has the capacity to understand other people, comprehends the world in a more meaningful way, and even more, copes with its own internal dialectics. Thus, we can claim that all peoples are accultured. There is no human being without culture, and all peoples can be managed.

Over the past century, anthropologists have formulated a number of definitions of the concept of culture. Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952) cited over 160 different definitions of human cultures. If we accept that all peoples are living in an integrated environment, then we can draw a distinctive line between the natural and artificial world. The natural life is an evolutionary phenomenon in which all creatures are subrogated. The artificial world is the cultural life of all human beings who have made their cultures. Therefore, culture is the product of the human mind. According to Taylor (1871: 1), culture refers to: “That complex whole which includes knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man (or a woman) as a member of society.” We will define the concept of culture as everything that human beings think, do and have as members of a society. Thus, all cultures comprise (1) philosophies, (2) sciences, (3) arts, (4) information, (5) political ideologies, (6) technologies, (7) behavioral patterns, and (8) religious dogmas.

Perceptual Paths of Cultural Philosophies

Today, many people in different cultures perceive the reality of their lives based upon traditional philosophies and beliefs about the old view of the cosmos and human nature. Most East Asian cultural philosophies perceive that “the present and tangible of the broad daylight and plainly visible is the real life” (Mason, 1967: 30). Such a conception of the cause of existence is more oriented toward the earthward imagery movement. Although cultural images of European and American nations examine the present and future, they exhibit individualism, humanism, and pervasive optimism. The traditional Oriental cultural view has been marked by institutionalism, materialism, and technological utopianism (technological utopianism is true in today’s Occidental cultures too). They also have made distinctive characteristics between genders in both cultures.

In reviewing the international cultural dimensions of Asian, American, European, Middle Eastern, and some African cultures, we find three imagery philosophies in the evolution of these cultures. The three perceptual timelines—past, present, and future—illustrate a transition from early optimistic views of a better society to the more recent challenges about the future. This means that as much as a society is more advanced in regard to technological innovativeness, the more it becomes a futuristic oriented society. Although cultural images of most American, European, and Near Eastern nations deal with the present and future, they exhibit individualism, humanism, and pervasive optimism in regard of the future.

The traditional solipsist Far Eastern cultural philosophies—from India through China, Hong Kong, Thailand, Korea, Japan, and others—have not made a differentiation between the human and the divine. Etymologically, the word cultural-philosophy in most Western cultures means “the love of God,” and the “love of Wisdom.” However, in most Eastern Asian cultures, cultural philosophies perceive that the path of life has been regarded as originally the way of the spirits of Heaven extended into the material universe, and no other way is considered to exist (Mason, 1967). The solipsist East Asian cultural theory indicates that the self is the only object of verifiable knowledge. It is that nothing but the self exists. These two controversial beliefs are differential milestones in both East Asian and Western cultural philosophies. In the literature dealing with cultural images of both East Asian and Western cultures, there are three key concepts which are frequently used interchangeably: cultural ideology, cultural myth, and cultural utopia (Vlachos, 1978). It is necessary to distinguish among both East Asian and Western cultural aspiration of the meanings and ends of these three key word concepts.

Cultural Ideology

Cultural ideology is relatively a recent concept of the early twentieth century which has been defined as all systems of thoughts that aim at justification and preservation of the status quo (Mannheim, 1946). Cavanagh (1990: 2) defines status quo as: “An ideology is a worldview which is built upon and reinforces a set of beliefs and values.” For example, the idea of progress, which has been a defining ideology in Western civilization, was built on a set of beliefs that arose with industrialism. There is an argument called social Darwinism on competition in human culture. Herbert Spencer (1888) was a European philosopher who popularized the doctrine called social Darwinism. Spencer’s philosophy offered a moral basis for the accumulation of large wealth through economic competitive operations. Spencer believed that life is a continuing process of adaptation to harsh external environments. Consequently, according to this philosophy, businesses are engaged in competitive struggle for survival in which the fittest will survive. Darwin (1842) confined his principles of evolution to plants and animals, but Spencer found his own laws of development and decay everywhere—in biology, psychology, sociology—even in the evolution of planetary systems. The social Darwinism ideology stands on competition in the business world; it weeded out the unfit and drove humanity in upward motion toward betterment. There are three main philosophical cultural phases of evolutionary sequences in the business world.

At first, there is a phenomenon of concentration as in the formation of clouds, the contraction of nebulae (as resembling plutocrats: concentration of wealth), the accumulation of elements leading to the formation of elementary living cells. Some historians cite that the Revolutionary War of 1775–1783 in America was fought to free plutocratic colonial business interests from smothering British mercantile policies (Ver Steeg, 1957). The prominent historian Charles Beard (1913) argued that the U.S. Constitution was an “economic document” drawn up and ratified by propertied interests for their own benefits. His thesis was and remains controversial, in part because it trivializes the importance of the American philosophical, social, and cultural forces in the policies of constitutional adoption. In those days, the economy was 90 percent agricultural, so farmers and planters were major elements of the American political elite. In this setting, two fundamentally different sociocultural and political ideologies clashed, and one was victorious. These two cultures were industrialism and agrarianism. The ideology of industrialism derived from the basic tenets of capitalism and equated progress with economic growth and capital accumulation. The ideology of agrarianism extolled the virtues of a rural nation of landowners (Steiner and Steiner, 1997: 328–329).

Second, there will be a gradual differentiation or specialization of structures that are so impressive in the evolution of organisms (innovative shifting from property wealth to knowledge wealth or vice versa). Hamiltonian sociocultural philosophy was opposed by agrarian interests. Thomas Jefferson and his followers developed the ideology of agrarianism. He trusted in a rule by commoners. He also believed that heavy industrial development had undesirable consequences. He believed that government became a plutocracy (Steiner and Steiner, 1997).

Third, determination will occur: what Herbert Spencer means by this is that the appearance of factors that maintain integration and unity sustain the wholeness that is threatened by differentiation (the World Wide Web information superhighway with integration of all human knowledge: e.g., Microsoft). When these processes reach a certain point, a climax is reached. Differentiation becomes too complex and declines.

Nevertheless, the widespread acceptance of Spencer’s doctrine made predatory behavior seem acceptable. In the following quotation, John D. Rockefeller, speaking in a Sunday school address, made the following comment. His remark was quoted in the article by Hofstadter (1970: 37):

The growth of a large business is simply a survival of the fittest… . The American Beauty rose can be produced in the splendor and fragrance which bring cheer to its beholder only by sacrificing the early buds which grow up around it. This is not an evil tendency in business. It is merely the working out of law of nature and a law of God.

Evolutionary ideology in the field of international business reinforces values such as optimism, thrift, competitiveness, and freedom from elite interest group interference (Steiner and Steiner, 1997: 22). However, tensions frequently arise between cultural ideologies. For example, the heavy concentration of great wealth, which is justified by Marxism in centralized socialistic governments, can be translated into social power, which, in reality, will conflict with the tenets of democracy that offer mass population the right to check ruling elite classes in the exercise of power.

In the twentieth century, among many revolutions, two major revolutions stood out. First, in the former Soviet Union and, second, in Iran. The populace accepted autocratic ideologies, such as czarism in Russia prior to the Bolshevik Revolution (1917) and monarchism in Iran prior to the Islamic Revolution (1979). This could be perceived as the price of having ruling powers capable of manipulating national wealth. The consequences of such ideological conflicts caused tensions between rival ideologies, ignited political movements to topple both monarchies, and led the Russian and Iranian people to be exposed to other types of authoritarian power.

Cultural Myth

Cultural myth and millennial visions, on the other hand, are characterized by what may be called traditional consciousness. Here, the emphasis is on the past and on the scarce and timeless understanding of life. Some philosophers have emphasized the similarities between myth and ideology; others have stressed the differences. This disagreement stems in part from the tendency to describe the numerous connections between myth and ideology in actual social and political systems, on the one hand, and the tendency, on the other hand, to define them in analytically separate terms. To present philosophers, it seems necessary to do both of these things: in the first place, to define myth and ideology separately, then to describe their relationship in concrete social systems—the sociopolitical complexes of various societies. Perhaps this point can be illustrated by an analogy. If a chemist were so impressed by the frequency of the hydrogen-oxygen complex that they failed to define the two elements independently, then the chemist would be unable to deal with them when they occurred separately in their pure forms, or, more commonly, when they appeared in compound with other elements. To define culturally both oxygen and hydrogen separately, however, would in no sense be a denial of the phenomenon which is water. It is, to be sure, quite unusual for myth or ideology to appear in “pure” form; but it is very common for them to be found in “compound” with other systems. Myth and religion, for example, and ideology and politics are frequently interrelated in complex societies.

De George (1990: 5) states: “The Myth of Amoral Business expresses a popular, widespread view of American business. Like most myths, it has several variations. Many people believe the myth, or somewhat believe it. It expresses a partial truth at the same time that it conceals a good deal of reality.” For example, the Rockefeller myth is one of the events which has attracted much attention. When John D. Rockefeller was at the zenith of his power as the founder of Standard Oil Company, he handed out dimes to rows of eager children who lined the street. Rockefeller was advised by a group of public relations experts who believed the dime campaign would counteract his widespread reputation as a monopolist who had ruthlessly eliminated his competitors in the oil industry. Rockefeller believed that he was fulfilling some sort of humanitarian responsibility by passing out dimes to hungry children. However, the dime campaign myth was not a complete success. Standard Oil was broken up under the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (Kreitner, 1998: 131).

Cultural utopia, in its classical sense, is similar to myth in that it often conceptualizes time as recurrent and not historical. However, utopia also includes a vision of things and phenomena hoped for, the substance of things not seen. Utopias are characterized by visionary consciousness with emphasis on the future. Human beings have always had a yearning for utopian paradise and for a society better than their own. In the utopian vision of their hopes and efforts, they quest for a better individual lifestyle and a collective achievement to fulfill their moral and societal obligations. In trying to describe utopian mentality, men and women realized that their visions have been the constant companion of their societal life (Parhizgar, 1996). However, the human mind, by its imitative nature, does not bring changes in cultures, because people in ascribed cultures are trapped in the swamp cultures of values that do not exist. For example, some authorities believe that free trade among nations is an idealistic way to do business around the world. This ideal, however, takes different forms. One form it takes for Milton Friedman (1962) is that people should be able to engage in economic transactions free from governmental interference or other types of human coercion. The rationale for this utopian vision of freedom is based upon the idea that “no exchange will take place unless both parties benefit from it.” If the parties benefit from the trade transaction, and it does not harm anyone, then, the transaction has been culturally valuable. So people around the world with freedom of choice and exchange will, in doing what is in their own best interests, generally be doing what is culturally valuable as well (Shaw and Barry, 1998). However, it is impossible for corporations to be able today or in the near future to reach such utopian ideas. In addition, free choice and free exchange promote the “invisible hand toward coercive power” to manipulate freedom.

Primitive Cultures

Our approach to studying multiculturalism is systematic, not historical or biographical. Some attention to the history of theories, however, may help us reach a systematic statement. A fundamental feature of multicultural theory is that it is a comparative one. Perhaps this can be done effectively by stating that some of the features of the origin of cultures can look at both conceptual and perceptual behavior in the widest possible context, ranging from the most technologically simple for aging societies at one end of the continuum to the most highly sophisticated and complex societies at the other. It seems that the phenomenon of culture reaches back tens of thousands of years in the history of human beings. It seems that the story of the origins of human culture has been built out of the flimsiest of archaeological, philological, and anthropological evidence, then filled out with psychological and sociological guesses. The observations of the early scientific studies of culturalogy were based largely on data drawn from living preliterate societies. Therefore, those illiterate societies with simple technologies, art, and creativity, once referred to as “primitive,” are described by contemporary cultural anthropologists by other terms such as “preliterate,” “small-scale,” “egalitarian,” or “technologically simple.” Maybe it is not fair to call our ancestral culture “primitive,” because if they could express their ethical and moral judgment about today’s culture, they may call us “primitive.” Because they are closer to the origin of simplified humanity. Owing to the misleading implication that something “primitive” is both inferior and earlier in a chronological sense, the term primitive will be avoided if possible in this text. Ferraro (1995) has used the term “small-scale” cultures and refers to those societies as those that:

have relatively small populations,

are technologically simple,

are usually preliterate,

have little labor specialization, and

are unstratified.

Swamp Cultures

People in swamp cultures may think that they are independent and start going off in other directions. But political ideologies and/or religious dogmas switch these deviated subcultures right back into their mythical modes (Covey, 1993). Swamp cultures are cold societies in which citizens work without any privileges such as educational and training opportunities, without equitable distribution of income and wealth, and without human rights. They just follow the political idealogies and/or religious dogmas. How can a swamp culture be turned into an attractive oasis? In order to transform a swamp culture into an oasis, people should be mentally multiculturalized. The transformation process requires patience, time, work, and tolerance.

Human beings, through their historical cultural synergy, have extended their multicultural ability to process information generation by generation. They have communicated the results of their findings through the development of artificial, computer-based information systems.

Oasis Cultures

Oasis cultures prosper from long-term commitment to the utopian cognitivism of ethical and moral transformation of individuals, as parts of society as a whole, to comply with the universal truthfulness, righteousness, goodness, fairness, justness, trustworthiness, empowerment, and alignment. The result can be called human civilization. Oasis cultures value teamwork, spirit, courage, earnestness, perserverance, and heroism. In sum, in an oasis culture, people envision the world in which the chief values are truth, beauty, and love. Are human cultures moving in such metaethical directions?

The growing intercontinental integration of the world economy (e.g., the North American Free Trade Agreement—NAFTA; the European Union— EU; Southern Cone Common Market—Mercosur) pushes human societies into a multicultural borderless future. In the era of multiculturalism of the business of trade and free flow of information, knowledge first, then capital, goods, and finally services are flowing to places where they earn the best returns, not necessarily where governments would like them to go. The development of international knowledge-based information superhighways can create an appreciation for multinational organizations in order to globalize their operations. Hill Jr. and Scott (1992: 6) state that: “One of the major consequences of these changes is increased emphasis on meaning cultural diversity, a situation in which several cultures coexist within the same organization or the same society.” In a broader context, it can mean people from several countries working together to achieve their shared goals.

Gender Cultures

Men and women can speak the same language universally. However, men assume that, similarly, men and women should be able to perceive and understand each other equally. If the latter proposition is true, then in an Oriental or Occidental organization, do women exert the same managerial power within their workplace as men do? Ferraro (1995: 222) indicates that: “One need not be a particularly keen observer of humanity to recognize that men and women differ physically in a number of important ways. Men on average are taller and have considerably greater body mass than women .… Men have greater physical strength. Men and women differ genetically… . Humans are sexually dimorphic.” From another angle: in the nature-nurture debate, do men and women behave differently because of their genetic predisposition or because of their culture? The definition of femaleness and maleness varies widely from culture to culture. Owing to this cultural variability in behavior and attitude between genders, most anthropologists now prefer to speak of gender differences rather than sex differences (Ferraro, 1995).

It is sufficient to say that most languages around the world are culturally sexist. In both Oriental and Occidental languages, we can find clearly that the pronouns and verbs for male and females vary. The Persian language, Farsi, is not a sexist language, because there are no different pronouns and verbs for male and female and/or for the third person. For example in the English language we use: “he” for a man and “she” for a woman. But in the Persian language there is only one pronoun for the third person which is “Oo;” it does not make any difference whether it is a man or a woman. Maybe this is one of the reasons that Persian immigrants, when they speak English, do not add “s” after the verbs for the third person. In addition, in most cultures, when women marry men they lose their last names and change them to the husband’s name. In the Persian culture, a married woman keeps her own identity and maiden name through her married life.

In general terms, the classical study of gender research indicates that women are communicative, intuitive, nurturing, sensitive, supportive, and persuasive (Schwartz, 1989). Researchers found that most women have a higher sense of the importance of long-term relationships (Covey, 1993).

Women’s and men’s social roles are not the same throughout the world. Every culture has established certain expected behavioral trends and values about women’s and men’s family and societal roles. For example, in describing gender differences in American families and institutions, Zinn and Eitzen (1993: 128) state: “We distinguish between a perspective that treats role differences as learned and useful ways of maintaining order in family and society and a structural approach…. Of course, gender is learned by individuals and produces differences in the personalities, behaviors, and motivations of women and men .…” In addition, traditional gender roles in the United States concerning differences between men and women have been established through their socioeconomic characteristic roles as breadwinner and housewife. Ferraro (1995: 233) states: “Males who are frequently characterized as logical, competitive, goal-oriented, and unemotional were responsible for the economic support and protection of the family. Females, with their warm, caring, and sensitive natures were expected to restrict themselves to child rearing and domestic activities.” In supporting the men’s and women’s behaviors that are different, Goldberg (1983: 11) states: “The feminine woman is sensual, not sexual. … A woman learns as a little girl that sex is nasty—sometimes men manipulate women to get something women grant as a gift and use as a source of power to control men .… The masculine man, on the other hand, is sexual but not sensual. He wants sexual relief but is uncomfortable with non-goal directed holding and caressing. Consequently, he approaches sex mechanically… .” This is why a man can very easily marry a woman, but a woman cannot easily marry a man. It is a gender characteristic that men work primarily so well in positions of power and influence and like to take advantage of these positions in a risky manner (Parhizgar, 1994: 524).

Conceptualization of Multicultural Civilization

Cultural diversity includes differences among minority and majority groups in language, religion, race, culture, and politics; ethnic heterogeneity characterizes societies on every continent. Social scientists maintained for many years that industrialization and the forces of modernization would diminish the significance of race, ethnicity, and religiosity in heterogeneous societies (Deutsche, 1967). However, in our contemporary societies, the free flow of information through networking navigation has broken down particularistic social units. Nations are not isolated through rigid political doctrines. If citizens of a radical nation physically are prohibited to travel around the world easily, they have found a way to travel freely around the globe mentally and communicate with others through the World Wide Web.

The emergence of large multinational corporations and alliances has caused particularistic nations’ loyalty and identity to be directed primarily to the free flow of commodities in the international market. These corporations brought many ethnicities and races together to synergize their production systems.

Analysis of multiple cultures is complicated by variations in culture within an organization, which often reflects variations within the society in which it operates. As previously indicated, in human organizations, there is usually a widely shared or mainstream culture and a set of subcultures (e.g., popular culture, hip-hop culture, elite culture, folk culture, counter culture, common culture, national culture, international culture, business culture, high culture, Hollywood culture, Hispanic culture, Anglo culture, Afro culture, and religious culture). In addition, there are often varying degrees of acceptance or rejection of the key values of each culture (Duncan, 1989; Gregory, 1983).

Multiple cultures exist in today’s highly industrialized nations for several reasons, the most obvious of which is that industrialized nations such as the United States of America have found that the key success for innovative competitiveness is multiversity. A group of people with different races, ethnicities, nationalities, gender, colors, ages, religions, and political ideologies is known as cultural multiversity. Within such a multiverse society, a multiplicity of cultural value systems may also exist as the result of the merging of all these subcultures into a holistic culture (Higgins, 1994:472).

In a traditional form of strategic cultural analysis, cultural resources, which could be defined as tangible and intangible resources, include everything that might be perceived as the strengths or weaknesses for both human civilization at large and a given culture. Several researchers have attempted to derive categorization of human civilization.

Cultural Resources Fitness

There are a number of ways in which cultural resourse-based fitness can be further developed. Barney (1991) suggested that resources could be grouped into physical, human, and capital categories. Grant (1991) added to these financial, technological, and reputable resources. Wheelen and Hunger (1995) viewed resources on a continuum basis to the extent which they can be duplicated by others (i.e., transparent, transferable, and replicable). At one extreme are slow-cycle cultural resources, which are durable and enduring beliefs, ideas, values, and practices. These are shielded by conceptual philosophy, theoretical scientific findings, technological processes, and, in extreme cases, by dogmatic religious faith. At the other extreme, there are fast product life cycles (PLCs) of international cultural resources available to people to imitate them. These cultural PLCs of value systems, such as fashions, enforce tremendous pressures on people to imitate new modes of behaviors. Although all categorical classification of cultural resources are very useful in strategic decision making, these categories bear no direct relationship to Barney’s (1991) initial criteria for utility, namely, value, rarity, difficulty in imitation and copying, and unavailability of substitutes.

This view is based on categorization of all cultural sources and resources into tangible and intangible resources, namely property-based resources, and knowledge-based resources with the utility values of potentiality, availability, causality, accessibility, durability, and profitability.

Knowledge-Wealth Civilization

Some cultural artifacts—either physical-based or knowledge-based resources—cannot be imitated because they are protected by property rights, contracts, deeds of ownership, or by special national interest prohibitions. Other resources are protected by knowledge barriers; by the fact that competitors do not know how to imitate a cultural artifact’s process or operation (Miller and Shamsie, 1996). In reality, they cannot be imitated by other cultures because the resources are subtle and hard to understand. They involve talents and specific technological devices which are elusive and whose connection with results is difficult to discern (Lippman and Rumelt, 1982). In addition, some knowledge-based cultural civilizations often take special scientific procedures and procedural skills: technical, integrative, synthetic, creative, and collaborative (Fiol, 1991; Hall, 1993; Itami, 1987; Lado and Wilson, 1994).

The increasing globalization of knowledge-wealth, scientific intellectual property copyrights, technological patents, informational integrated discoveries, accumulation of innovative manufacturing techniques and innovative services of both infopreneurial and entrepreneurial cultures prompt questions about contextual knowledge spillover at both domestic and international cultural niche. Rahmatian (1996: 147) states: “Infopreneur is a term coined by Skip Weitzen in 1985 to denote a person who gathers, organizes, processes, and sells information as value-added business ventures. A decade ago, the concept of infopreneurship, its value-added nature, and its supporting technologies were all valid as evidence by a multitude of real-world success stories.” The national knowledge-based fitness offers a nation an appropriate international niche in order to adapt their ideas and ideologies very effectively and to deal with cultural competitors efficiently. Such knowledge-based cultural resources may have what Lippman and Rumelt (1982) called “uncertain immutability.”

Research and development (R&D), historically, used to perceive its role as upholder of leading quality and standards of innovative knowledge and innovative manufacturing systems. Within the domain of manifestation of new trends in production and consumption systems, the “fragmented domestic market segmentation” of the business world has been converted into holistic international market economic philosophy. By specifying the distinctive advantages of holistic philosophy of a market niche, it may be possible to add comprehensive precision to the research. According to the traditional modes of market niche of Miles and Snow (1978), competing domestic firms within a single industry can be categorized on the basis of their general strategic orientation as one of four types: defenders, prospectors, analyzers, and reactors. Such formulated strategies are contingent upon external environmental forces. Organizations strive for a fit among internal organizational culture, strategy, and external environmental forces. Nevertheless, rivalry cannot avoid the high cost of resources and low pricing systems for consumers.

Today, on the basis of free flow information through the World Wide Web (WWW) and with spillover information, multinational industry leaders and international academic world experts view their mission in justification of their cooperative international alliances in terms of this “philosophy.” That is in the “absolutist terms” of this philosophy, what costs less is necessarily better, and quality finds reflection in the “lower cost” of the knowledge, science, and information “products” not in the properties inherent in them. In addition, to complement an industry and/or a firm’s internal fitness of resources, it needs to delineate the external environmental forces in which different kinds of resources would be most suitable and profitable. Thus, the result of this philosophy is an “optimum cost” analysis in the international market economy.

From another dimension, within the domain of infopreneurial “research sourcing,” there are different distributive channels for innovative competitiveness. These channels could be found through knowledge exploration, scientific discoveries, informational acceleration, and technological development. However, within the boundaries of international infopreneurial market economy knowledge-based product life cycles (PLCs), all are not moving along the same venturing path of truth-finding of the value-added outcomes. Of course, a major philosophical problem in the infopreneurial marketplace is based upon the questions: How do we have the assurance that we know something is suitable? How do we really know that we know the truthful applicability of our knowledge in problem finding and solutions? Why do we know what we must know? Why do we do things in this way? Why do we not do it another way (Jordan, 1996)?

Responding to these and other questions requires an illustrative aggregated dichotomy of rationalization which identifies object from subject and being from not being, through application of both tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is a talent for learning a kind of practical knowledge that can only be acquired through experience. Explicit knowledge is a systematic and easily communicated form of hard data or codified procedure. However, the astonishing diffusion of tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge is kinesthetic knowledge, which shows that everything that is organizing is organized, and everything that is organized is organizing. That thing is recognized as intelligence.

In reenergizing a cultural knowledge-based fitness for more economic meaningfulness of all human activities, there is a need to conceptualize a critical question. That question is: Why should we not apply the right knowledge correctly in order to energize our civilization sufficiently? In reinventing the knowledge enterprise, there is a fundamental cause that is carefully realized by its foundational philosophies. That cause is: Why do we apply a specific right knowledge? Is there any other right knowledge? If yes: Why should we not rightly acquire it?

Knowledge-wealth acquisition is assumed to be acquired either through “direct sourcing” in innovation and exploration of the scientific research methodology or through spillover of innovation of imitated information and technological systems. In addition to the main objectives of this chapter, we are trying to analyze three fundamental philosophical knowledge-based cultural dimensions. These are epistemological, ontological, and axiological value-added cultural products of knowledge within the boundaries of info-preneurial and entrepreneurial civilization in the international free market economy.

Epistemological Knowledge-Based Civilization

As we mentioned in the previous chapter, epistemology refers to the problem of knowledge: in particular, how is knowledge acquired? How is it possible? What does knowledge mean? Can all knowledge be traced to the great gateway of the senses, to the senses plus the activity of reason, or to reason alone? Do feelings render wordless but true knowledge? Does true knowledge ever come in the form of immediate intuition? In responding to these questions, there are two basic points which need to be addressed: (1) What is knowledge? and (2) How do we obtain knowledge? Knowledge has long been an integral part of human life (Weber, 1960). The Greeks chose to classify knowledge into two types: doxa (that which is believed to be true) and episteme (that which is known to be true). The problem is a straightforward one: since human beings cannot transcend their cultural system, they therefore cannot obtain any absolute viewpoints. The solution is to define knowledge in an alternative fashion, one where knowledge is only “asserted.” Knowledge is therefore not infallible but conditional; it is a societal convention and is relative to both time and place (Hirschheim, 1985).

The set of knowledge conventions is not arbitrary. They are well thought of, having the produced knowledge which has withstood the test of time. Knowledge could be acquired through meditation, consultation, and/or an oracle. This form of knowledge acquisition might be considered “unscientific” because it does not match the conception of science, but since knowledge is simply the process by which an understanding is obtained, philosophically it cannot necessarily dismiss these attempts. Spinosa (1898) states:

It has now been made clear that the passage from the state of bondage to the state of freedom requires the assiduous application of reason. Not only the emotions, but also the whole order of the Nature must be studied, and the continuous study of the causal order of Nature leads ultimately to the highest kind of knowledge. At this level, the mind no longer views things merely as finite and temporal, but rather, it grasps their essential characteristics under the aspect of eternity.

Therefore, knowledge is a particular set of assertions of philosophical understanding.

Historical conception embedded in our civilization shows that knowledge is a holistic dominance of positivitism. Knowledge is an understandable attempt to know what the alternatives are. The search for knowledge is a search for the real, and the knowledge gained is absolute, universal, and objective. Spinosa (1898) believed in three kinds of knowledge: “Knowledge of the first is mere belief or imagination; knowledge of the second kind is scientific knowledge or knowledge of cause and effects; and knowledge of the third kind is ‘intuition,’ in which individual things are understood through a comprehension of God.” Epicures (1926) states that our understanding can be realized through philosophy, because philosophy is the quest for knowledge. Thus, in the world today all scientific, intuitive, imaginative, and innovative understanding of self and the whole universe are bounded with a holistic knowledge.

Ontological Knowledge-Based Civilization

Ontology reveals: What does it mean to exist? What is the criterion of existing? What are the ultimate causes of things being generalized as to what they are (causality) (Weber, I960)? The Persian philosopher Avicenna (1380/1960) examined the human civilized culture on the basis of existence and accidents, matter and form, unity and multiplicity, and wisdom and sensation. Ontological concepts can be used to analyze many micro topics. Philosophy is an active quest for true knowledge and a way of looking at the knowledge that we have. It is helpful to consider at least two ways of thinking about philosophy: (1) philosophy as a process, and (2) philosophy as a content. In philosophy as a process, philosophers actively engage in the “doing” of philosophy. They not only answer very specific questions, but they also question answers. Philosophy as a content finds philosophers passively observing philosophy as it is (or was) practiced by others. Whether technical or casual, one’s philosophy of life is important. Philosophy is important because it reflects human feelings and attitudes as well as conscious wisdom and conventional intelligence (Weber, 1960: 5). Many cultural beliefs, if not most ideas, are powerful agents of wisdom and intelligence in humanity. If cultural beliefs and ideas have any bearing on action, they tend, as it were, to leave the head and enter the hands, then human knowledge can be viewed as a universal truth.

Axiological Knowledge-Based Civilization

Axiology is concerned with the problems of value systems. The most viable traditional field of inquiry in information systems is ethics. It is concerned with the problems of good and bad, right and wrong, and truthfulness and false information. Ethical genealogy insists that knowledge and information power are implicated in each other. Ethics shows how knowledge not only is a product of information power but also can be a nonneutral form of abusive power. The genealogical moral, ethical, and legal approaches to the dissemination and disclosure of information are interdisciplinary issues. Genealogy, as Nietzsche argued, is a prima facie means of de-essentializing phenomena (Kaufman and Hollingdale, 1967).

The veridical knowledge-based information systems often are successful precisely when they deny (or they are denied) their power to intervene. Ethical, moral, and legal genealogy not only investigate obscured continuities of traditional cultural beliefs and political ideologies through a networking access, such as the knowledge-based and information-system connections, they also can be regarded as the social history of discontinuations and current knowledge as lacking their traditionally asserted intellectual unity. In such a domain, there are two major issues to be addressed. First, knowledge-based information systems are highly disciplinized within the field of computer science; however, they may not be highly disciplined within the fields of social sciences—the way in which scientific and technological order is imposed on disunified information systems. Discipline in its ethical and moral terms is the infrastructure of truthful embodiment of information which should be extended to the behavior and conduct of both informants and information users. Second, attention to the use of knowledge-based information systems is not merely about organizational social commitments, it is above all the concern about integrity of human identity (Parhizgar and Lunce, 1994). Therefore, in the new infopreneurial market, knowledge-based information systems should be institutionalized.

Structural Dimensions of Cultural Philosophy

In conceptualization of the cultural philosophy of a nation, apart from its substantive content, several structural dimensions seem significant. They include the degree of formalization, the degree of abstractness, and the degree of affectivity.

Degree of Formalization

A prevailing cultural philosophy of a nation, which could be called a manifest functional structure, contains the sole statement of ideological, mythical, and utopian beliefs which a nation perceives. Also, it contains societal doctrines and religious dogmas to be perceived “on the way” toward the more general and ultimate objectives. Similarly, it contains specification of means—that is, alternative faiths and expectations in the social structure, and procedures that contain high probability of attaining the cultural goals.

Degree of Abstractness

Cultural philosophies may vary also in the degree to which they are abstract or concrete. As citizens use a cultural doctrine philosophy, it is an abstract. But it provides legitimate rights and duties through their ethical and moral commitments. The problem is in variability of concrete interpretations. For instance, in some cultural doctrines of a few nations we find “equal opportunity in education.” But in implementation of this phrase we will find divergent interpretations and operational practices, which differ from their cultural doctrines.

Degree of Consistency

The degree to which the content of a cultural doctrine is consistent or integrated to the national sociopolitical objectives seems another dimension worthy of further cultural understanding. In this analytical domain, we should find out how a cultural doctrine is organized. With what degree of variation has it been formalized—simple as opposed to being complex or complicated? Related to the complexity, is the doctrine’s pervasiveness or scope very broad, and how much of societal life of the individual citizen is covered by that cultural doctrine?

Degree of Sociocultural Efficacy

A cultural philosophy could be analyzed, irrespective of its content, in terms of the degree to which it has effective or emotional qualities. In this matter, we should distinguish between the conceptual and perceptual value systems which necessarily commit the individuals and social organizations to its implicit value systems. A cultural philosophy, in our judgment, is ultimately acting as cultural faith in effectively endorsing certain ends in societal life and the degree to which it is phrased on irrelevant or highly tenuous grounds.

Multicultural philosophies can be defined as communicable thoughts, intellectual knowledge, and causal distinctive patterns in the human mind which separate acculturated from noncultured human beings. Differences in viewing the world we live in and the divine we believe in could be attributable to multicultural philosophical meanings. Most Asian cultural philosophies do not have differentiated values between the human and the divine. On the other hand, cultural philosophies in the European and American countries have perceived that the universe originated from God as the first and sole cause, the creation of man was the final and most important step in creation, and God created the cosmos out of “waste” or “void” which existed with God before creation.

A cultural ideology is a worldview which is built upon and reinforces a set of beliefs and values. Cultural myth and the millennial visions are characterized by what may be called traditional consciousness. Some philosophers have emphasized the similarities between the myth and ideology; others have stressed the differences. To present philosophers, it seems necessary to do both of these things: in the first place, to define myth and ideology separately, and then to describe their relationship in concrete social systems—the sociopolitical complexes of various societies. Myth and religion, for example, and ideology and politics are frequently interrelated in complex societies. Cultural utopia, in its classical sense, is similar to myth in that it often conceptualizes time as recurrent and not historical.

Swamp cultures are cold societies in which citizens work without any privileges, such as educational and training opportunities, with inequitable distribution of income and wealth, and without human rights. Oasis cultures prosper through long-term commitment to the utopian cognitivism of ethical and moral transformation of individuals as parts and society at large to comply with the universal truthfulness, righteousness, goodness, fairness, justness, trustworthiness, empowerment, and alignment.

Chapter Questions for Discussion

How does gender dominate over males and females in all societies?

How similar are gender roles throughout the world?

Do males and females in the same culture perceive things differently?

How do you explain cultural philosophies of different nations?

How can cultural knowledge contribute to the style and function of cultural perception?

What is cultural philosophy?

What does cultural philosophy do?

Define the branches of philosophy below:

• Epistemology

• Axiology

• Ontology

Learning About Yourself Exercise #10

How Do You Believe or Not Believe in Your Own Cultural Philosophies?

Following are sixteen items for rating how important each one is to you and to your cultural value system on a scale of 0 (not important) to 100 (very important). Write the number 0–100 on the line to the left of each item.

![]()

As a philosopher, I strongly believe that:

_____ |

1. |

The universe is originated from God as the first and sole cause of existence. |

_____ |

2. |

God was real before the universe existed as an orderly cosmos. The nature of God is included the cosmos. |

_____ |

3. |

The creation of human beings was made in God’s image, i.e., as spiritual beings. |

_____ |

4. |

The cosmos has emerged as a necessity of material order. |

_____ |

5. |

The creation of the cosmos is viewed as out of “waste.” |

_____ |

6. |

Cultural philosophies are viewed as “social contracts.” Human beings raised themselves from a state of nature in which there were no rights, but only the rule of strength. |

_____ |

7. |

Only reason or intellect is the end or complete development of the natural things. |

_____ |

8. |

Life is like the egg which might develop into a chicken, but which might also, among other things, become an egg sandwich. |

_____ |

9. |

Human beings are not unique among the animal kingdom because they are rational. They are the technological and tool-making animals. |

_____ |

10. |

Intellectual people merely develop their abilities to think critically, to read others’ writings, to write their own ideas, and to speak without fear. |

_____ |

11. |

Human beings believe that the “mind’s eye” or introspection are the only realities that they can know directly and incontrovertibly. |

_____ |

12. |

The scientific conception of material things is something mental. It is a conceptual construct. |

_____ |

13. |

The extent to which we can understand the reality of life must be in an expression of mind. |

14. |

Reality of our life and knowledge are one and the same thing. When we die, our knowledge of self and the universe will die. | |

_____ |

15. |

We are living in a dog-eat-dog environment for survival. “Power” (e.g., political, financial, knowledgeable, and sexual) is the source of survival. |

_____ |

16. |

The laws of nature are thoughts, but they occur on an unconscious level. |

Turn to the next page for scoring directions and key.

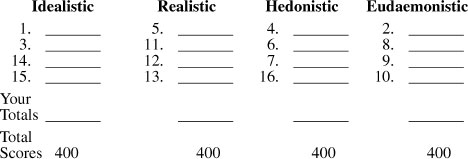

Scoring Directions and Key for Exercise #10

Transfer the numbers for each of the sixteen items to the appropriate column, then add up the four numbers in each column.

The higher the total in any dimension, the higher the importance you place on that set.

Make up a categorical scale of your findings on the basis of more weight for the values of each category.

For example:

1. 400 Essentialism | |

2. 350 Existentialism | |

3. 200 Realism | |

4. 150 Idealism | |

Your Totals |

1,100 |

Total Scores |

1,600 |

After you have tabulated your scores, compare them with others on your team or in your class. You will find different judgmental patterns among people with diverse scores and preferred modes of self-realization.

Case Study: The La-Z-Boy Company

Management may at any time determine that the managerial philosophy of a corporation should be changed in order for the company to be able to survive. Whatever the intent, it is clear that management philosophy does affect organizational structural hierarchy and manufacturing operations. The resulting structural or restructural designs reflect the new vision, image, goals, and objectives of a company. Indeed, the historical cultural philosophies of many organizations reflect the personalities of their top managers. The La-Z-Boy Incorporated’s new multicultural managerial philosophy supports the evidence that managerial philosophy can enhance or retard an organization’s operation.

The Floral City Furniture Co. was founded in 1929, which later on, on May 1, 1941, became La-Z-Boy, Inc. in Michigan. The company was founded by Edward and Edwin Shoemaker and was family run until 1998. The present name was adopted on July 30, 1996. In 1976, La-Z-Boy Inc. sold 50 percent interest to La-Z-Boy International Pty. Ltd in Australia. In February 1979, Deluxe Upholstery Ltd. of Canada was acquired with net assets of $3,048,266. In January 1986, the capital stock of Rose Johnson, Inc. was acquired. In January 1988, all of the capital stock of Kincaid Furniture Company, Incorporated, was acquired for $53,000,000 in cash which included $26,500,000 in goodwill. On April 1995, England/Crasair was acquired for $2,600,000 in cash, $10,000,000 in notes, and $18,000,000 in common stock. During the fiscal year of 1997, the company acquired 75 percent of Centurion Furniture shares from England. In February 1998, the company entered an agreement to acquire Sam Moore Furniture Industries Inc. The company is planning to buy 100 percent of Moore’s outstanding shares if the offer prevails.

Everyone in the United States has probably owned or sat on a La-Z-Boy recliner. La-Z-Boy is well known for manufacturing recliners, but that is not all they manufacture. The company manufactures upholstered furniture throughout the United States for business, produces office seating, desks, and cabinets. Also, the company manufactures patient care seating for clinics, hospitals, and homes. The company’s headquarters are located in Monroe, Michigan. In the United States, twenty-nine manufacturing plants are operated, most with warehousing capacity. It has an automated fabric processing center and has divisional and corporate offices.

When Charles Knabusch died at fifty-seven, a family dynasty ended. Edwin Shoemaker, age ninety, died soon after Charles, and when Charles’ wife, June, asked for a seat on the board, she was turned down because since 1997 she owned only 2 percent of the $52.7 million shares. Problems could have arisen from this radical change, but they were not serious enough to bring La-Z-Boy down. Chairman Patrick Norton’s decision could be considered as unfriendly, and disloyal to the founding family, in economical, sociological, psychological, and professional terms. First, Norton’s decision could be considered as unethical because after he had steadily worked as vice-president for the company for several years under the family-oriented structure, once both Knabusch and Shoemaker died, Norton decided to change the company’s cultural value system and image. Such a drastic change destroyed the family structural image of the company. Second, Norton’s decision was economical because the change brought in more revenue and broadened the company’s La-Z-Boy stores. Third, Norton’s decision also had psychological impact on both La-Z-Boy’s shareholders and employees who had associated with one another for many years. Finally, Gerald Kiser, an operational executive of La-Z-Boy was promoted to president; he raised the sales to $1.2 billion (revenues). Managers as well as factory employees are now happy with their jobs, consumers are satisfied with the good quality of the products that La-Z-Boy has brought to the market, and shareholders are very happy with their increased earnings.

Sources: Barron, K. (1999). “Does Reclining Mean Decline? La-Z-Boy Hopes Not: Company at a Crossroads.” Forbes, January 25: 60; Rabum, V. P. and Kiedaish, H. D. G. (2000). Moody’s Industrial Manual. New Y ork: FIS, A Mergent Company: 5903–5904.