Multicultural Paradigm Management Systems and Cultural Diversity Models

Without multiple sources of knowledge, there will be no power to shed light on our minds.

When you have read this chapter you should be able to:

develop conceptual skills to understand different philosophies and practices of cultural diversity models and multicultural paradigm management systems,

identify the three groups of cultural diversity models,

indicate the principal concerns of multicultural paradigm management systems, and

describe how multiculturalism can enhance multinational organizational operations.

Radical political changes and the free flow of information characterized the early 1990s on the socioeconomic maps of the world. Many nations found themselves in a new international condition, which has been called the “new world order.” Consequently, businesses concerned with international implications for their operations faced new challenges and opportunities, as well as new threats. The new world order caused many nations to come freely from every corner of the globe to break down most political barriers. For example, Hanebury, Smith, and Gratchev, (1996: 54) state that: “Russia is rapidly moving to a free economy. Nearly 40 percent of its economy was privatized by the end of 1993. U.S. exports of manufactured goods to the newly independent States reached an annual rate of $108 billion in 1993, a five-fold increase compared with 1992.” In addition, many multinational corporations have experienced successful expansion ventures into Eastern European countries. Therefore, the globe becomes a small place, but friendly only to those who are prepared to understand it and to change their traditional views from cultural diversity to multiculturalism to work within it.

The difference between cultural diversity and multiculturalism cannot be explained with a single analytic tool or with two general models. It is necessary to understand that the nature of scientific research makes such a difficult job an almost foregone conclusion. Researchers found no absolute distinctive explanations or theories to identify exactly the final outcomes of their efforts; any theories pose more questions than they answer.

In this chapter, therefore, we will find no scientific explanations that have been tested and/or retested about cultural diversity and/or multicultural theories. However, we should not ignore the basic philosophical approaches when building cultural models for multinational organizations.

In viewing differences between cultural diversity models and multicultural paradigm systems, we can focus our attention on the relations among different groups who are living together within a specific geographical boundary. Since multinational corporations must establish an integrated global philosophy in which they can encompass both domestic and international operations, they need to realize that their mission is bounded with global sourcing, operations, marketing, and sales strategies. They must identify how to synergize their corporations through multicultural philosophy in order to be competitive in the international markets. For these and other reasons, they must be prepared to accept the frustration that often accompanies new ideas about potential cultural problems that may be confronted in different markets.

Although multinational corporations with their global operations often are classified as either global or multiregional corporations, most multinational corporations are mixed. They handle some of their operations with considerable global integration while conducting their internal organizational operations on the basis of their home country’s multidomestic strategies. Any corporate operation, internationally, must make trade-offs between the advantage of practices of global multiculturalism and those of the multitude of cultural diversity practices in home countries.

A Comprehensive Approach Toward Multiculturalism

The study of cultural relations in home and host countries is concerned generally with the ways in which the various groups of multiethnic, multicolor, multireligious, and genders come together and interact over an extended period of time. As we proceed in our investigation, we will be looking specifically at two major models of culture: (1) multiculturalism and (2) cultural diversity. For clarity in our study, we pose three key questions:

What are the basic fundamental beliefs and practices concerning intercultural relations in the global market? As we will find out, intercultural relations commonly take the form of both competitive alliances and conflicts. Alliances synergize their competitive potential through partnership, and conflicts result in hostile takeover of an industry or a corporation. Just as we will be concerned with understanding why conflict and competition are so common among multinational corporations, it will also be our concern to analyze harmonious conditions of cooperation and coordination among home and host countries.

How do dominant giant multinational corporations in the global market maintain their positions at the top of the international market hierarchy, and what attempts should be made to synergize their positions? Dominant multinational corporations employ a number of direct and indirect strategies to protect their financial power and operational opportunities in their home and host countries. Subordinated cultures do attempt to change this arrangement from time to time. In fact, if multinational corporations do not attempt to integrate the general host’s cultural value systems into their corporate cultures, it may result in organized movements against multinational corporations. Therefore, one of the chief concerns will be the ways in which multinational corporations learn how to diffuse the host’s econopolitical hostility into their corporate strategies.

What are the long-range effective outcomes of the multicultural paradigm model in the global market? When a multinational corporation builds up its corporate culture through multicultural philosophy and practices, then multicultural value systems can exist side by side in the same market for a long period of time. They either move toward some form of economic partnership, integration, and unification, or they maintain and even intensify their differences. Again, our concern is not only these outcomes, but it is also with analyzing the sociocultural and econopolitical forces that favor both producers and consumers.

Analytic Study of Multicultural and Cultural Diversity Models

As we have analyzed the corporate cultural value systems of some multinational organizations, we have discovered that great differences exist between their theoretical perspectives and practical operations. This is understandable because free flow of international information and workforce diversity is emerging as a new field without a commonly accepted theoretical basis. However, building a multinational corporate cultural model is as important as managerial structures and business strategies.

Gorry (1971: 1–15), in his research, indicates that general characteristics for building a model include the following:

Good models are hard to build. Convincing models that include managerial role variables containing direct implications for actions are relatively difficult to build.

Good parametric assessment is even harder than the selection of the right models. Measurement and data assessment should be processed in such a way that they are effectively relevant to the objective outcomes. This requires high quality work at the design stage and is often very expensive to be carried out.

Models should be understood by the users. Usually, people tend to reject models when they perceive too much complexity by application of that model in action.

A model must capture the basic dynamic behavior of multinational organizational incumbents in order to explain all tangible and intangible forces within the system.

For these purposes, the selection of a multicultural paradigm model in this text will serve as a beginning point in processing multicultural interactions within multinational organizations. Although the model applied in this text is useful to study multicultural behavior, the model has not been objective as to which assumptions are warranted and whether one yields more satisfactory outcomes than other assumptions.

Societies are complex systems. Criteria of either cultural homogeneity or heterogeneity can be applied to any and/or all of their valuable facets. These criteria could be assumed as their class structure, power distance, language barriers, ecological features, topographical conditions, and so on. The present interest in this text focuses on the extent to which a society can be regarded as culturally homogeneous, heterogeneous, and/or a mixed culture.

The concept of cultural homogeneity or heterogeneity refers to the ethnic and/or cultural identity of an individual (De Vos, 1980: 101). Theoretically, culturally homogeneous societies are made up of citizens and/or residents who all possess more or less the same ethnic identification. It has been argued that a country such as Japan comes close to that condition. At the other end of the continuum is a nation such as the United States, which has always been regarded as culturally diverse. The salience of cultural diversity is the extent to which it matters whether one individual does or does not belong to a particular group.

Multicultural Management Paradigm System

A paradigm is a basic framework through which we conceive and perceive the world, giving shape and meaning to all our knowledge, experiences, providing a basis for interpreting and organizing our both conceptions and perceptions (Palmer, 1989: 15). A paradigm is more than a theory because it is the synthesized essence of our mind and actions within the historical events of our culture. A paradigm is a fundamental asserted belief that sometimes is not even articulated until brought into question by someone else’s new competing paradigm. Since multinational corporations have operated in the various international markets with application of different international theories, in reality, they are faced with serious competitive challenges and/or personal attacks by some host countries. For this and other reasons, multinational corporations must find new solutions for survival and continuity of their operations in the various international markets. One of the solutions is to establish a new path of conceptual and perceptual views concerning their operations on the basis of multicultural paradigm model.

A Model of the Impact of Multiculturalism

With the increasing volume of foreign investments and international trade operations a deep understanding of forces within the marketplace and market space and skills to manage different forces will be the keys for successfully managing multinational corporations. Hofstede (1993: 81) found that international application of management theories are different in home and host countries. He indicates: “Management as the word is presently used is an American invention. In other parts of the world not only the practices but the entire concept of management may differ, and the theories needed to understand it may deviate considerably from what is considered normal and desirable in the USA.” He found that in a global perspective, U.S. management theories and practices contain a number of idiosyncracies not easily shared by management elsewhere. Three such idiosyncracies are:

a stress on market processes,

a stress on the individual, and

a focus on managers rather than on workers.

By taking a systematic approach to design and implement the kinds of changes required by the diverse cultural workforce in multinational corporations, a new organizational structure must also be designed to manage a multinational corporation’s operations.

In recent years, it has become commonplace for one discipline to borrow terminology and models from another. Conceptual, biological, mechanical, and ecological frameworks have cross-fertilized scientific endeavors in most social sciences. The concept of multicultural models, now well established in the field of international business, has similarly spanned across such disciplines as political sciences, organizational theory, military sciences, and cultural diversity. Researchers were using cultural diversity models long before the term “model” became a key word in international management vocabulary. However, in the age of free flow of information around the globe, the matter of developing models for multiculturalism is not a simple one. There are too many complex processes in building such models.

Table 9.1 presents the multinational management model of multiculturalism (M4), which in this text has been developed on the basis of learning from research of the relevant literature, consulting, and teaching experience over the past four decades. There are three major dimensions within the boundaries of thirteen features of a model that this text applied as somewhat distinctive.

Table 9.1. A Multinational Management Model of Multiculturalism (M4)

Home Countries’ Cultures |

Host Countries’ Cultures |

Multinational Organizational Culture |

|---|---|---|

Individual-Level Factors |

Group/Intergroup Factors |

Achievement Outcomes |

|

|

|

First, this is a holistic model designed to explicate effects of multicultural versatility for many multinational organizations with consideration of characteristics of both home and host countries. Since multinational corporations operate within various international markets, they need to consider three major cultural interest group objectives: (1) home cultures of joint venturing partnership, (2) host cultures of subsidies, and (3) corporate organizational culture.

A second point of distinction concerning the M4 is that it treats holistically organizational constituencies in a more cohesive manner than the traditional management systems. Since the practical decision-making processes of traditional international management systems are based upon focusing on race, ethnicity, national origin, gender identification, and physical identification, the M4 views certain similar effects of multiculturalism on home and host countries, along with the multinational organizational outcomes. For example, in the United States, organizational employees have typically been classified as blacks, whites, Hispanics, and others. In the Arabian nations, employees are classified as Arab and Ajam (non-Arab). In Australia, people are identified as Aborigines and Europeans. In all of these categorical stratifications, the evidence of discrimination contains ethnicity and racial identity and puts emphasis on physiological features, color of skins, and cultural differences among people. The end result is segregation of minority groups from majority. If multinational corporations use racial and/or ethnicity as the basic criteria for recruitment and promotion, they are depriving themselves of multinational synergistic efforts.

Three Modes of the Multicultural Paradigm Scale

Usually multicultural paradigm models possess their own characteristics and objectives that should be completely comprehensive to users. Multinational corporations and domestic businesses are facing the challenge of more multicultural workforces. Grant (1996: 123) has observed that successful and large-scale intervention efforts of cultural diversity management models proceed through six definable and predictable stages: confrontation; dialogue; experiential learning; challenge, support, and coaching; action-taking; and organization and culture change.

The model of multicultural behavior in this text is concerned with the key elements of organizational stimuli within the behavioral context and the consequential managerial facilitator’s outcomes. This model can either mitigate the tension between employees and employers and/or energize observable and nonobservable problem-solving consequences.

The twelve stages of the intervention cycle of the multicultural paradigm model of this text are:

confrontation,

dialogue,

experiential learning,

challenge and competition,

coaching,

action-taking,

organization and culture change,

creating new organizational structure,

free labor movement,

meritorious equal employment opportunities,

sociopolitical cultural diversity, and

cultural adjustment.

Table 9.2 illustrates each stage with possible counteractions of these forces by the facilitator management system.

Table 9.2 Multicultural Behavioral Paradigm Model of Facilitator Management

Source: Parhizgar, K. D. (1999) “Comparative Analysis of Multicultural Paradigm Management System and Cultural Diversity Models in Multicultural Corporations.” Journal of Global Business 10(18), Spring, p. 52.

Table 9.2 provides an in-depth view on multinational organizational management systems. It can be applied to regional economic integrations and free trade agreements among neighboring nations. The model identifies the major variables in multinational organizational management systems and also provides solutions for multicultural managerial synergy. Unlike the most behavioristic cultural diversity models, which have emphasized the need to identify observable signs of sociopolitical and economic contingencies for the prediction and control of behavior of organizational incumbents, the expanded multicultural model of this text recognizes the reciprocal interactive natures of home and host cultural value systems, the persons’ cognition, and the behavioral outcomes in decision-making processes and actions.

Three Major Models of Cultural Diversity

Harvey and Allard (1995: 3) have clustered cultural-diversity models into three major groups:

Those groups that focus on the individual (Table 9.3),

Table 9.3 Diversity Models Centering on the Individual

Type

Focus

Theorists

Static

Individuals: dimensions on which they differ from each other

Loden and Rosener

Static

Individuals: major group memberships

Szapocznik and Kurtines

Static

Individuals: incompatible cultural values

Rivera

Source: Harvey, C. and Allard, J. A. (1995). Understanding Diversity: Readings, Cases, and Exercises. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers, p. 4.

Those groups that emphasize the development of sensitivity (Table 9.4), and

Table 9.4 Diversity Models Centering on Sensitivity

Type

Focus

Theorists

Static

Sensitivity: elements in development (individual) of cultural sensitivity

Locke

Static/ Dynamic

Sensitivity: stages in sensitivity learning

Hoopes, Bennett

Source: Harvey, C. and Allard, J. A. (1995). Understanding Diversity: Readings, Cases, and Exercises. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers, p. 5.

Those groups that center on the organizations (Table 9.5).

Table 9.5 Diversity Models Centering on Organizations

Type

Focus

Theorists

Static

Organization: Individual, intergroup, and organizational factors

Cox

Dynamic

Organization: Action plan for changing organization climate

Thomas

Dynamic

Organization: Organizational factors matched to individual needs

Jamieson and O’Mara

Dynamic

Organization: Corporate approaches to managing diversity

Palmer

Dynamic

Organization: Melting Pot Model

Zangwill

Cultural Pluralism Model

Kallen, and Steinberg

Civic Culture Model

Fuchs

Source: Harvey, C. and Allard, J. A. (1995). Understanding Diversity: Readings, Cases, and Exercises. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers, p. 6.

Models of Individual Cultural Diversity

There are three submodels of individual cultural diversity:

Primary and secondary dimensions of diversity

Panoramic photography of pulls of diverse family generations and nonfamilial environments

Incompatible cultural values

Primary and Secondary Dimensions of Diversity

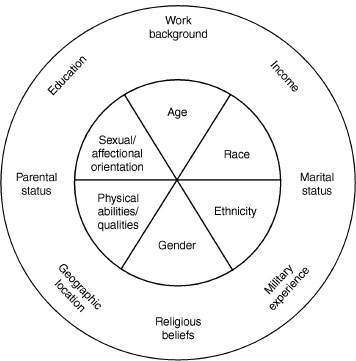

Loden and Rosener (1991: 20) distinguish between primary and secondary dimensions of diversity, which identify characteristics of people that do not change, and secondary dimensions of characteristics which can be changed. Figure 9.1 displays the relationship between central or primary characteristics and those that are secondary in nature. Loden and Rosener claimed that women are more likely than men to manage in an interactive style—encouraging participation, sharing power and information, and enhancing the self-worth of others. Rosener claimed that women tend to use “transformational” leadership, motivating others by transforming their self-interest into goals of the organization, while men use “transactional” leadership, rewarding subordinates for good work and punishing for bad.

Figure 9.1. Primary and Secondary Dimensions of Diversity

Source: Loden, M. and Rosener, J. (1991). Workforce America! Managing Employee Diversity As a Vital Resource. Homewood, IL: Irwin, p. 20.

Panoramic Photography of Pulls of Diverse Family Generations and Nonfamilial Environments

Szapocznik and Kurtines (1993: 400–407) also built their model on the basis of focusing on the individual, but from a broader perspective. Their model is a panoramic photography that illustrates the individual within the family, embedded within an environment compromised of diverse cultures. This model identifies that the individual faces the pulls of diverse generations as well as the pulls of a diverse nonfamilial environment.

Incompatible Cultural Values Model

Rivera’s (1991) model of cultural diversity (see Figure 9.2) is based upon how managers view the world and how they learn to succeed in it. Although individual cultural values, background, talents, and training contribute to each individual’s unique experiences, this model provides a base from which you can begin to understand the differences—subtle and striking—that minority people face.

Figure 9.2. Incompatible Individual Cultural Values Model

Source: Rivera, M. (1991). The Minority Career Book. Holbrook, MA: Bob Adams, Inc. Publishers, p. 15.

Figure 9.2 illustrates a comparison between a set of “traditional” cultural values and a set of “contemporary” cultural values, and/or a historical domestic values and a set of modern international values.

Models of Sensitivity Development

There are three models of sensitivity learning diversity:

Cultural assimilation

External/internal diversity awareness training model

Dynamic approach in intercultural sensitivity learning

Cultural Assimilation

Locke (1993: 1–13) has built his model of cultural diversity on the basis of sensitivity learning in order to increase emotional and sensational binding toward other cultures. This model places individuals in a series of widening contexts (family, community, cultural, and global) that influence sensitivity, and then the model describes elements to explore for a better understanding of other cultures. For example, individual sensitivity learning in Japan is emphasized through cultural pragmatic experiences. Rohlen reports five major sensitivity learning programs for a Japanese employees’ bank. The philosophy for such training programs is based on an assumption that employees should focus on loyalty in order to fulfill their roles. Loyal employees are identified by their moral obligation to work hard for their company (Rohlen, 1973: 1543). This model contains five stages in its training program.

Stage 1: Zen Meditation

The trainees should visit a famous Zen temple and spend a few days there. The Zen monks teach them how to embrace a very austere regime with equanimity. They believe such training will reduce anxiety. Trainees should learn concentration with thoughtful meditation, along with controlled breathing. Then the Zen monks will ask trainees to concentrate on their serious problem. They show how, by meditation, they can overcome their problems. In Japanese culture, the workplace is assumed to be a family environment. Therefore, the result of this type of training will stimulate their mind to reduce selfishness and enable them to work with other organizational members in harmony, cooperation, and sharing.

Stage 2: Military Training

Japanese people should visit military bases in order to develop behavioral discipline and material order within a group. Military training teaches soldiers the spirit of determination, devotion, and fulfillment of their mission. A part of this training is the lecture on “mission in life.” This lecture is inspired by the kamikaze pilots (suicide squads) of World War II. Trainees are inspired by kamikaze volunteers who knew that Japan would lose the war and that their suicidal missions meant certain death. They were committed to proceed with it because they were soldiers and because of their willingness to serve their country rather than to pursue individual pleasure.

The author of this text experienced such a behavioral mentality during the Iran and Iraq War, in the 1980s. The Khomeini regime used to apply such a technique for young soldiers to defuse mines in the battle zone through spiritual suicide actions. It should be indicated that in the cases of both Japanese and Iranian cultures the age similarity between the suicide war heroes and the trainees proved to be a striking point.

Stage 3: Rotoo

Rotoo is voluntarily working for strangers without pay. This is a tradition in Japanese culture that promotes a sense of brotherhood among Japanese people. This tradition clarifies the meaning of work in which the enjoyment of succeeding depends on the person’s attitude toward it. Also, it shakes the trainees out of social lethargy by using self-volunteer perception. They must ask acceptance of strangers without social crutches, such as rank or family. The bottom line of this type of training program is to stimulate the spirit of Japanese youth toward self-esteem. It forces trainees to ask themselves: “Who are we?” Self-realization is the major objective of this type of training program for satisfactory achievement in a strange environment.

Stage 4: A Weekend Among Farmers

Working in an agricultural community can establish a sense of harmony with the natural environment. This exercise provides appreciation of social interdependence and social services as well as for the more self-aware and self-reliant nature of farm people and a fostering of the ingenuity of the simplicity in the farm living. This type of training program is stimulated to appreciate the hardworking people in the Japanese community, and to establish a sense of “searching for the last grain in the lunch box.”

Stage 5: An Endurance Walk

The final capstone is physical exercise that requires trainees to walk twenty-five miles: nine miles as a group, nine miles in smaller squads, and the last seven miles alone, in silence. The objective is to create a feeling of endurance and tolerance for walking a long distance. Competition is not the point; all they must do is finish the course. Of the last seven miles, Rohlen (1973: 1555) reminisces: “I could see that I was spiritually weak, easily tempted and inclined to quit.”

Terpstra and David (1991: 51) indicate that: “Overall, the training program stressed: (1) the importance of teamwork, (2) the close relationship between physical condition and mental well-being, and (3) the importance of dogged persistence in accomplishing almost any task.”

External/Internal Diversity Awareness Training Model

Johnson and O’Mara (1992: 45–52), in their experimental research for 27,000 employees at Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), have applied four key behaviors for measuring the effectiveness of diversity awareness. They are:

self-knowledge,

leadership,

subject matter understanding and expertise, and

facilitation skills.

They found that managing diversity training programs improves the corporation’s competitive advantage in recruiting and retraining both line and staff employees. The end result is to improve productivity, quality, creativity, and morale.

Dynamic Approach in Intercultural Sensitivity Learning

Bennett (1986: 182) has developed a pragmatic intercultural photograph of intercultural sensitivity learning. This model is based on a learning continuum: at one end is ethnocentrism and on the other is ethnorelativism. This continuum identifies three stages for each end: denial, defense, and minimization for ethnocentrism; and acceptance, adaptation, and integration for ethnorelativism (see Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3. Stages of Development in Experience Differences

Source: Bennett, M. (1986). “A Developmental Approach to Training for Intercultural Sensitivity.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10(2), p. 182.

Models of Organizational Cultural Diversity

Organizational cultural diversity has been perceived as a situation in which several cultures coexist within the same organization or the same society (Higgins, 1994: 427). In a broad context, it means people from several cultures working together. Although the focus is on the ethnic origin of both majorities and minorities, in a broader context the term includes women and older workers, as well as people from different nationalities, working together in an organization. Five major models of cultural diversity have been established. They are:

The conceptual model of diversity

The flex-management mind-set model

The intermediary organizational roles model

The three paradigms of cultural diversity models

The melting pot, cultural pluralism, and the civic culture models

However, it should be noted that in all of these models the utilitarian philosophy of distribution of wealth and power has prevailed. Utilitarianism philosophy views that justness is the greatest good for the greatest number of majority cultural groups.

The Conceptual Model of Diversity

Cox’s (1993: 1) conceptual model of cultural diversity is based upon a social system that is characterized by majority and minority groups. The majority group is the largest group, while a minority group indicates a group with fewer members represented in the social system compared with the majority group. On the basis of sociopolitical ideology of the cultural diversity model of Cox, the majority group signifies that members have historically held advantages in sociopolitical power and economic resources compared with minority group members. Cox (1993: 6) indicates: “In the United States, organizational examples are found in industries such as insurance and banking, in which the work force is typically 60–70 percent female but the management ranks typically have more men than women.”

Usually, the cultural diversity model identifies both larger quantitative number of people from one culture to maintain greater power and economic advantages to other minority groups. As Cox (1993: 6) indicates: “In most large corporations in the United States, White American men of full physical capacity represent the largest, most powerful, and most economically successful group.”

The Flex-Management Mind-Set Model

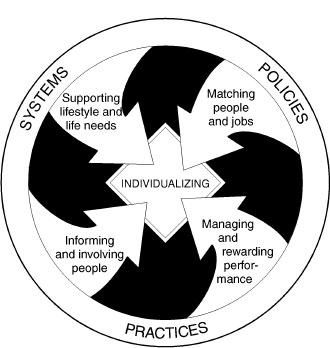

Jamieson and O’Mara’s (1991) flex-management model is a new mind-set model which is different from other models (see Figure 9.4). Flex-management philosophy is based on a set of core cultural values that provides specific conceptual thoughts as frameworks for decisions and actions. The flex-management philosophy is the antithesis of a “one size fits all.” It requires management to tune in to people and their needs in order to create options that give people choices and balance diverse individual needs with the needs of the organization.

Figure 9.4. The Flex-Management Mind-Set Model

Source: Jamieson, David and O’Mara, Julie (1991). Managing Workforce 2000: Gaining the Diversity Advantage. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, p. 37.

The structure of this model is based upon three principles:

systems,

policies, and

practices

All three of these components can serve diversified cultures.

The flex-management model is based on four principles:

A deep appreciation of individual differences and understanding that equality does not mean sameness

People are viewed as assets to be valued, developed, and maintained

Management is based on the value of greater self-management, which leads to provide more options that people select themselves

Management-flex is the mind-set of flexibility not rigidity

The Intermediary Organizational Role Models of Cultural Diversity

For multinational business operations within cultural diversity, companies must play three roles in order to succeed:

organizer,

interpreter, and

multicultural mediator

These three roles should be kept separate and should be assigned to different departments in order to avoid conflict of interest (Heskin and Heffner, 1987: 525).

Three Paradigms of Cultural Diversity Models

Palmer’s (1989: 15–18) three different paradigm models of cultural diversity models have created different opportunities for different cultures. These paradigms are:

The golden rule

Right the wrongs

Value the differences

The Golden Rule Paradigm of the Cultural Diversity Model

The fundamental imagery of the golden rule paradigm is that we should treat everyone the same. People should judge themselves and others on the basis of equality and avoid biased judgments. The golden rule paradigm model conceptualizes oppression as coming from only a few “bad’ or ‘‘prejudiced” people in isolated incidents. Differences among people are due to individual characteristics.

The Right-the-Wrongs Paradigm of Cultural Diversity Model

The fundamental imagery of the right-the-wrongs paradigm model is that specific groups in an organization, as well as in a large society, have been systematically disadvantaged. It is not the wish of managers to treat employees differently and continue these injustices, but the system has been designed that way. Managers want to change the system. The main objective of cultural diversity under this model means the establishment of justice for specific targeted groups. Once justice has been established, the same principles would be applied to other disadvantaged groups. The class-cultural struggle can emerge under this paradigm management system. Therefore, the targeted group’s strategy is based upon the belief that “no one gives up power—you have to take it.”

The Value-the-Differences Paradigm of Cultural Diversity

The fundamental imagery of the value-the-differences model is that differences among individuals in an organization are appreciated because differences can cause synergy. So the effectiveness of cultural diversity is greater than the sum of all of its parts. Under this paradigm, treating and grouping everyone the same is rejected. The synergistic result of differences among employees and treating them differently can energize the organization by using and rewarding the talents of all types in the organization. A phrase for this paradigm management system is “value all differences.”

The Melting Pot, the Salad bar, and the Civic Cultural Models of Pluralism

In the past decade, several researchers published articles and books dealing with cultural diversity in the United States. Schlesinger Jr. (1992: 137–138) calls for an appreciation of cultural diversity while cautioning that the foundation of American culture is adapted Europeanism and that repudiation of that heritage would “invite the fragmentation of the national community into a quarrelsome spatter of enclaves, ghettos, tribes.” Culture wars are derived from different and opposing bases of moral authorities, ethical beliefs, and religious faiths within worldviews (Hunter, 1991: 43).

Gates Jr. (1992: 176) asserts that by common sense “we are all ethnic, and the challenge of transcending ethnic chauvinism is one we all face.” Therefore, these and other advocates of cultural diversity believe that the prospects for understanding multiculturalism seem bleak. However, cultural diversity occurs in our daily life at all levels of society and we cannot ignore it.

Today, many organizations are beginning to implement new approaches to cultural diversity and are responding to a range of new issues. Among new cultural diversity models, the three models of Carnival and Stone (1995: 13) are of great interest. They indicate that it is a debate concerning culture wars that has raged since the founding of the United States, taking different expressions with each generation. Whatever the case, diversity issues have deep roots in America’s history. Three models of cultural diversity are:

The melting pot

Cultural pluralism

The civic culture

Melting Pot Organizational Culture (MPOC)

The title of Israel Zangwill’s play (1909) The Melting Pot has often been used as a metaphor to describe the phenomenon of people changing their names, learning a new language, and adapting their cultural values to blend into other cultural lifestyles, which all occur when people immigrate to a new country. The MPOC indicates that the ideal objective of a nation is to assimilate people into a unified system through public cultural trends in order to reduce the cultural and structural divisions between minority and majority groups (Zangwill, 1909: 198–199). In The Melting Pot, Zangwill invoked the “Great Alchemist” who “melts and fuses” America’s varied immigrant population “with his purging flames.” Although today the validity of such a metaphor is often questionable in terms of adapting to lifestyles outside of organizational work, in the workplace certain norms, values, and beliefs usually are based upon certain ethnic experiences that dominate the whole society (Harvey and Allard, 1995: 40). However, those immigrants who believe in keeping their motherland’s cultural identity never blend in; even if they have an option, they feel they should maintain their cultures. These groups of people believe that if they assimilate themselves into a new culture, they are in the denial of their own cultural identity. This can result in a further denial of the way in which they believe.

According to Abramson’s (1980: 150–160) views, under the MPOC model there are three possible forms of complete assimilation. Each involves a different path and a somewhat different objective. First, minority cultures may assimilate into the dominant majority groups. Second, minority cultures may assimilate into an entirely majority culture. This is the popular notion of the “melting pot,” in which all minority cultures surrender their ethnic heritage but in reality they create a hybrid society. In an international view, Israel is a modern melting pot on such a course. Third, minority cultures may assimilate into another nondominant cultural background.

In a corporate cultural perception, the traditional metaphor of the melting pot organizational culture is based upon the “management” value system which mandates their beliefs along with conformity, conservatism, and obedience to the rules, willingness for team playing, and loyalty in all aspects of an organization. This type of organizational culture is similar to the “mechanistic” one, which indicates that assimilation of a “stranger” into the cultural streamline of a host country would probably have survival for a cause. It also indicates how new employees tolerate ethnic prejudice, biased comments, and jokes. Usually, those blue-collar workers assimilate themselves very easily into the new organizational culture. This has been viewed as the sole cause to continue working: in order to guarantee the breadwinner responsibility for his or her family.

In a MPOC, usually employee turnover rates escalate when people think that they are valued for their differences, not similarities. Harvey and Allard (1995: 41) indicate that: “When diverse employees are subject to sexual harassment, ethnic jokes, homophobic attitudes, organizational policies and practices that do not support them, they either leave, sue, or stay but contribute less to the organization.”

The mechanistic organizational culture emphasizes quality improvement and cost reduction (Schoderbeck, Cosier, and Alpin, 1991). This approach motivates corporate managers to believe that most jobs should be highly structured with minimum pay. Consequently, the corporate culture forces employees to ignore their own personal values and assimilate themselves into the corporate melting pot culture. The corporate managerial value systems in MPOC emphasizes efficiency—”doing things right,” instead of perceiving and maintaining “doing the right things.”

In today’s international business transactions, multinational corporations cannot implement the MPOC because the trends of conducting businesses changed dramatically in the 1990s. Multinational businesses are moving toward global multiculturalism because managers perceive that their success is bounded to globalization, rather than domestication, of their businesses. Today, global corporations are learners and collaborators with host nations rather than being hierarchical and controlling toward them.

The MPOC value systems perceive that to do what the corporate culture has been doing is a matter of strategic fact. However, it should be noted that in today’s international free market economy, nearly 40 percent of U.S. corporate profits result from overseas investments (Toak and Beeman, 1991: 4). By the year 2000 it is estimated that one-half of the world’s investments will be controlled by multinational corporations (Feltes, Robinson, and Fink, 1992: 18–21).

The philosophy of the MPOC is based upon the creed of “doing business better.” However, this belief in efficiency changed dramatically due to the new world order—from “doing business better” to “doing the right business.” The new world order has changed the course of business transactions. Competition in the contemporary marketplace in most developed countries becomes intense to such an extent that all corporations face very unstable environments. In an intense competitive marketplace, change and change agents are destabilizing the environment. Consequently, multinational corporations are exposed to very shaky environments both at home and in host countries (Harvey and Allard, 1995: 3).

In modern societies such as the United States, corporations do not perceive enculturalization anymore. They are thinking of and practicing accommodating and even appreciation of diversity. No longer do U.S. corporation managers think in terms of assimilation; instead, they think and perceive of “managing” diversity.

Salad Bar Organizational Cultural Diversity (SBOCD)

In most developed nations, there is no longer a melting pot corporate cultural philosophy in businesses. Organizations are exposed to cultural diversity forces. Cultural diversity increases—with cross-functional, cross-discipline, and cross-national work teams—the frequency of international sociable contacts. What was taken for granted as international interactions in professional work organizations are now viewed as the maintenance of multiculturalism.

In a mechanistic and/or melting pot corporate cultural environment in the 1960s and 1970s, according to Alpin and Cosier (1980: 59), an efficiency-oriented maintenance structure was beneficial for an organization in a relatively stable environment. Gradually, in the late 1980s, this pattern of corporate culture was changed to the organic culture and/or salad bar organizational cultural diversity. The SBOCD promotes diversity instead of homogeneous work identity. Heterogeneity in the professional workforce involves a high tolerance for cultural diversity. Heterogeneity in corporate cultures manifests a new value system with few rules and regulations, open confrontation of conflicts, risk-taking behaviors, tolerance of whistle-blowers, and more respect for employees’ personal moral and ethical beliefs and expectations.

The SBOCD emphasizes “effectiveness” to give careful consideration to shaping, reinforcing, and channeling the corporate culture toward high quality and productivity in the corporation. Such a drastic shift causes corporate managers to depart from “mechanistic” and/or melting pot cultural mentality to “meritocratic” and/or fragmented culture. For example, historically, due to the changes in technologies and diversity of population, the U.S. government deregulated many industries in the 1980s. There is some evidence that many multinational corporations, such as AT&T, have moved from a melting pot and/or mechanistic culture to a salad bar of “organic” culture. Tichy (1983: 254) supports this fact with the following excerpt on strategic change:

A major concern will be changing the cultural system. This will entail much strategic cultural change as represented by AT&T’s shift to support innovation, market competitiveness, and profit or by cultural changes which reflect new values regarding people, productivity, and quality of work life, as is also reflected in Westinghouse’s productivity efforts. The loss of world competitiveness by major U.S. firms is increasingly attributed to managerial failure, especially with regard to people management and the culture of the organization. Japanese management has paid careful attention to the shaping, reinforcing and channeling of their organizational cultures to support high quality and productivity.

Multicultural Organizational Civic Culture (MOCC)

Unlike the MPOC, the MOCC model entails several dimensions and forms. Multicultural pluralistic civic culture means that a society is composed of many different cultural groups through which the values, beliefs, and expectations are synthesized. At the same time that these groups are practicing their cultural value systems within the boundary of their cultures, they are valuing a general consensus cultural rule which governs equally over their society. Multicultural civic culture lays down certain expected behavioral rules as the “rule of the game.” These rules apply to all members regardless of their cultural group affiliation. Dealing with multicultural environments often raises problems, and often these conflicts are disruptive pressures over the whole society. The only trend that can bring together different groups is one in which radical group power is diffused. Then, in such a situation, no group has overwhelming power over all others, and each may have direct or indirect impact on others.

Multicultural pluralistic ideology cannot be found in all societies because it may be most effective in an environment which encourages pluralism. Multicultural civic culture is a new trend which is antiautocratic, antitheocratic, antiaristocratic, and antibureaucratic. It is based on natural rights and equalitarian ideals.

In the late 1990s, the shift toward multicultural organizational culture reflected the turbulence in many multinational corporate environments. Changes in consumer preferences, regional economic integration, relaxation in governmental trade policies, and economic conditions have caused nations to attempt to lessen segregation in various spheres (e.g., housing, schools, work, and politics) and to equalize access to power and privileges (e.g., affirmative action programs, voting rights) in many countries. However, the form and ultimate objectives of the global civic culture may vary in the minds of majority groups of policymakers as well as members of both dominant-majority and dominated-minority groups in different nations.

The MOCC model can be called an equalitarian harmonizer system by law. It is characterized by intercultural relations among diversified cultural groups designed by the law of a nation. Fuchs (1990) holds that civic culture is the unifying characteristic of American society and protects individual rights, including the right to diversity. He believes that the American experience is one in which diversity is recognized and protected by civic culture, and that the civic culture provides equal opportunity as a commonality. For example, in the United States there are four major laws: constitutional, statutory, common, and administrative (Mills, 1989: 97).

Constitutional law is a written document that is the highest form of law. All other laws must conform to its provisions.

Statutory law is the enactment of “laws” or “statutes” which Congress, state legislatures, and other representative bodies may enact.

Common law is the action of courts and the customs of the people constituting a body of law. Common law rests primarily on decisions of courts and upon the willingness of one court to follow what another has done (i.e., to follow “precedent”).

Administrative law is the regulations and decisions issued by governmental agencies for particular statutes.

Generally the civic cultural diversity model views diversified cultures as retaining their traditions for the most part, while participating freely and equally within common legal regulations. All diversified groups have given allegiance to a common cause, participate in a common economic system, and understand a common set of broad legal value systems.

The civic cultural diversity model can unify characteristics of American society and it is there to protect individual rights, including the right to diversity. According to Fuchs (1990: xv), “Since the Second World War the national unity of Americans has been tied increasingly to a strong civic culture that permits and protects expressions of ethnic and religious diversity based on individual rights and that also inhibits and ameliorates conflicts among religious, ethnic, and racial groups. It is the civic culture that unites Americans and protects their freedom—including their right to be ethnic.” In addition, Carnival and Stone (1995: 16) assert that the American experience is one in which cultural diversity is recognized and protected by the civic culture. In sum, within the boundaries of this model, there are two forms of cultural diversity: first, different cultural groups maintain their cultural and structural autonomy but remain relatively equal in justice bureaucracies. Second, the dominant majority cultural groups spell out the formal cultural values of society regardless of the characteristics of the dominated cultural minority groups. However, it is a fact that the dominant majority groups rule over minority groups on the basis of their historical legal terms. The best expression for this model is “the law of the land.”

Pluralism Cultural Diversity Model

Like the melting pot model, the pluralism cultural diversity model entails several dimensions and forms. Kallen (1915/1979) expounded an alternative model, cultural pluralism. According to his model, ethnic groups in the United States should retain their own identities while remaining loyal to the country and participating fully in national life. He believed that people should be respected for their contribution to the whole, not judged on the degree to which they are assimilable (Mann, 1979: 136–148).

Pluralism is the opposite of the melting pot model because pluralism is simply the condition that produces sustained cultural differences and continues heterogeneity (Abramson, 1980: 150). Marger (1985: 79) indicates that: “Pluralism is a set of social processes and conditions that encourages group diversity and the maintenance of group boundaries. Pluralism is never perceived as an absolute separation of minorities and majorities. However, through social processes, majority groups continue to maintain power and distribution of wealth with their historical traditions.” In sum, the pluralized cultural diversity model at some points is based upon this expression, that all diversified cultures are navigating their ships simultaneously in the ocean, and they may sink or swim together in that society.

In viewing differences among these modes of cultural perceptions, the focus should be attuned to the whys and wherefores of relations among different value systems of groups who are working together within a specific geographical boundary in contemporary international marketplaces. Since multinational corporations must establish an integrated global philosophy in which they encompass both domestic and international operations, they need to realize that their mission is bound with global sourcing, operations, marketing, and sales strategies. They need to identify how to synergize their corporations through multicultural philosophy to be competitive in the international market (see Table 9.6).

Table 9.6. Comparative Characteristics of Three Models

The previously discussed multicultural behavioral approaches have provided an in-depth view of multinational organizational management systems. They can be applied to regional economic integrations and free trade agreements among neighboring nations. These models identify the major variables in multinational organizational management systems and also provide solutions for multicultural managerial synergy. Unlike most behavioristic cultural diversity models, which have emphasized the need to identify observable signs of sociopolitical and economic contingencies for the prediction and control of behavior of organizational incumbents, the expanded multicultural civic model noted here recognizes the reciprocal interactive natures of home and host cultural value systems, individual cognition, and the behavioral outcomes in decision-making processes and actions.

For multinational business operations within multicultural organizational civic cultures, multinational corporations must play three roles to succeed: (1) organizer, (2) interpreter, and (3) multicultural mediator.

These roles should be kept separate and should be assigned to different departments to avoid conflicts of interest (Heskin and Heffner, 1987: 525). The managing multicultural organizational civic cultural model is a conceptual theory and researchers have found no logic in the valuing diversity argument to explicitly support their assumptions.

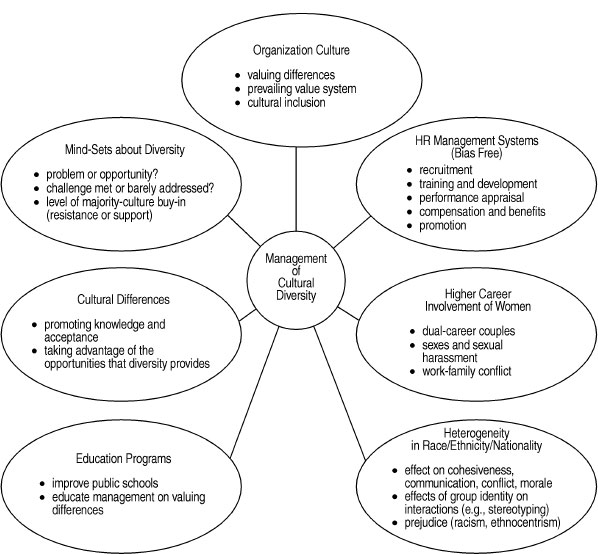

Managing Cultural Diversity Model

Cox and Blake (1991) have addressed a new theory for managing cultural diversity. The basic argument of this model focuses on how managing diversity can create a competitive advantage for a corporation (see Table 9.7). Cox and Blake viewed cultural diversity management on the basis of the social responsibility goals of organizations, which is only one area that benefits from the management of diversity. In addition, this model has focused on seven other areas in which sound management can create a competitive advantage:

Table 9.7. How Managing Cultural Diversity Can Provide Competitive Advantage

1. |

Cost argument |

As organizations become more diverse, the cost of a poor job in integrating workers will increase. Those who handle this well will thus create cost advantages over those who do not. |

2. |

Resource-acquisition argument |

Companies develop reputations on favorability as pro spective employers of women and ethnic minorities. Those with the best reputations for managing diversity will win the competition for the best personnel. As the labor pool shrinks and changes composition, this edge will become increasingly important. |

3. |

Marketing argument |

For multinational organizations, the insight and cultural sensitivity that members with roots in other countries bring to the marketing effort should improve these efforts in important ways. The same rationale applies to marketing to subpopulations within domestic operations. |

4. |

Creativity argument |

Diversity of perspectives and less emphasis on conformity to norms of the past (which characterize the modern approach to management of diversity) should improve the level of creativity. |

5. |

Problem-solving argument |

Heterogeneity in decision-making and problem-solving groups potentially produces better decisions through a wider range of perspectives and more thorough critical analysis of issues. |

6. |

System flexibility argument |

An implication of the multicultural model for managing diversity is that the system will become less determinant, less standardized, and therefore more fluid. The increased fluidity should create greater flexibility to react to environmental changes (i.e., reactions should be faster and at less cost). |

Source: Cox, T. H. and Blake, S. (1991). “Managing Cultural Diversity: Implications for Organizational Competitiveness.” Academy of Management Executives, 5(3).

education programs,

cultural differences,

mind-set about diversity,

organizational culture,

human resources management systems (bias free),

higher career resource acquisition, (involvement of women),

heterogeneity in race/ethnicity/nationality.

Figure 9.5 briefly explains their relationship to diversity management.

Figure 9.5. Spheres of Activity in the Management of Cultural Diversity

Source: Cox, T. H. and Blake, S. (1991). “Managing Cultural Diversity: Implications for Organizational Competitiveness.” Academy of Management Executives, 5(3).

The managing cultural diversity model is a conceptual theory, and researchers have found no logic from the valuing diversity argument explicitly to support their assumptions. Researchers are aware of no research article that reviews actual data supporting the linkage of managing diversity and organizational competitiveness.

In sum, if we revisit all of these models of cultural diversity with flexibility kept in mind, we may find some models more oriented toward monopoly on applicability of their ideological beliefs. Each model has a degree of validity—sometimes more than others. However, it should be indicated that they are all cultural diversity models which are always applicable to a portion of the population.

The main aspects of multinational organizational cultural relations between home and host countries are (1) the nature of behavior among different groups of people who are dealing with each other; (2) the organizational structure and the societal ethnic, race, gender, and religious relations in the international marketplace; (3) the manner in which the multinational corporation dominates or is dominated by special interest groups and/or how subordination among ethnicity of partner groups is maintained; and (4) the long-range synergistic outcomes of multicultural relations, that is, either emerging greater integration or increasing separation and segregation in partnership.

Chapter Questions for Discussion

What is cultural diversity?

What is multiculturalism?

State the difference between cultural diversity and multiculturalism.

What is a melting pot culture?

What is a civic culture?

With which set of cultural values, ethical and moral virtues, are we raised?

Discuss what is meant by cultural synergy?

Do you think all organizations have identical cultural characteristics?

How does cultural diversity affect majority and minority groups?

Which set of values, cultural diversity models, and multicultural paradigm management systems have been viewed? Describe philosophical and practical foundations of each model.

There is a trend today toward multicultural cooperation in multinational organizations. Discuss what this means in terms of the multidomestic, multiregional, and multinational value outcomes.

There is also an international trend in today’s multinational corporations concerning innovation toward synergistic organizational management. Discuss how this might affect someone from a domestic cultural value system.

Do you think all multinational organizations have identical missions and cultures? What does it mean for the stakeholders and stockholders?

Learning About Yourself Exercise #9

How do you Judge Yourself and your Cultural Orientation?

Following are fifteen items for rating how important each one is to you on a scale of 0 (not important) to 100 (very important). Write the number 0–100 on the line to the left of each item.

![]()

It would be more important for me to:

_____ |

1. |

Be proud of my ethnicity and/or race. |

_____ |

2. |

Recognize that freedom is the most important part of my culture. |

_____ |

3. |

Believe in individualistic ideology. |

_____ |

4. |

View other people as evil. |

_____ |

5. |

Believe that I am living in a discriminatory society. |

_____ |

6. |

Believe that our justice system is impartial. |

_____ |

7. |

View that I am living in an environment in which even wolves eat wolves. |

_____ |

8. |

Welcome other people to criticize my cultural values. |

_____ |

9. |

Communicate with other people from other cultures to learn new values. |

_____ |

10. |

Travel abroad in order to be familiar with other nationalities. |

_____ |

11. |

Prefer usually to talk in my own language while I am living in other countries. |

_____ |

12. |

To beat my competitors with all means and ends. |

_____ |

13. |

Get along with the majority of people and ignore my personal values. |

_____ |

14. |

Prefer to marry a person from my own ethnicity and/or race. |

_____ |

15. |

Prefer to get help from other people in order to be able to give help to others. |

Turn to the next page for scoring directions and key.

Scoring Directions and Key for Exercise #9

Transfer the numbers for each of the fifteen items to the appropriate column, then add up the four numbers in each column.

The higher the total in any dimension, the higher the importance you place on that set of needs. The closer the numbers are in the three dimensions, the more well sociopsychologically oriented you are.

Make up a categorical scale of your findings on the basis of more weight for the values of each category.

For example:

400 individualistically oriented

375 internationally oriented

200 ethnocentrically oriented

Your Totals |

975 |

Total Scores |

1,500 |

After you have tabulated your scores, compare them with others on your team or in your class. You will find different value systems of needs among people with diverse scores and preferred modes of self-realization.

Case study: The Blind Ambition of the Bausch and Lomb Company’s Cultural Mirrors in Hong Kong

Bausch and Lomb Optical Inc. (B&L) was incorporated on March 20, 1908, in New York. Today, it is a leading international company that develops, manufactures, and markets products and services for the optical and health care fields. The vision care segment includes contact lenses and lens care products. Pharmaceuticals manufactures and sells generic and proprietary pharmaceutical prescriptions. The health care division of the company provides biomedical products and services, hearing aids, and skin care products. The fourth segment of the company is eyewear, comprised of premium-priced sunglasses and optical thin film coating services.

Between 1994 and 1995, the business financial results of B&L Inc. were favorable. Net sales for 1994 were $1,892.7 million, growing in 1995 up to $1,932.9. But in 1996, the net sales took a slump, down to $1,926.8 million. Operating earnings were also favorable between 1994 and 1995, going from $119.8 million to $210.6 million. Dropping by 1996 to $190.8 showed a 9 percent change from 1995. The net earnings were $31.1, $112.0, and $83.1 million, respectively, exhibiting a 26 percent change from 1995 to 1996. The company’s inventories for 1995 were 304,300 and by 1996 they totaled 339,800. Total liabilities equalled $1,620,800 in 1995; by 1996 the liabilities had increased to $1,721,500.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Hong Kong was the star of B&L’s international division, often racking up an annual growth of 255 percent as it rocketed to about $100 million in revenues by 1993. The B&L in Hong Kong appeared to be a great investment for the stockholders.

Trouble appeared in recent years: some of the reported sales were faked, and the goods were not shipped. In the Cantonese language, the words ba dan mean “white sheet.” But for employees at B&L Inc.’s Hong Kong operation, they had another meaning: Ba dan signified a white invoice with a phony sales record on it. These secret ba dan invoices, which B&L headquarters never saw, would instruct staffers to send goods to an outside warehouse in Hong Kong. The headquarters soon found out the real reason for their great sales. Due to heavy pressure to maintain high sales, B&L Hong Kong pretended to book big sales of Ray-Ban sunglasses to distributors in Southeast Asia. In reality, the goods were not sent to the distributors but to the warehouses, and the unit would create secret ba dan invoices. Later, some of B&L’s sales managers tried to persuade distributors to buy the excess. Some of the glasses may also have been funneled into the black market. A buyer could profit by shipping them to Europe or the Middle East, where wholesale prices were higher.

By 1994, the international division of B&L was having trouble keeping up with the schemes and was showing falling revenues and climbing receivables due to the fake invoices that no one was paying off. The B&L headquarters in the United States sent a team of auditors to the division in Hong Kong. The auditors questioned Mr. Chan, the head manager of the B&L Hong Kong division, who claimed that tough pressures from top management to keep up with double digits allegedly forced them to fabricate the ba dan invoices. The company also suspected Mr. Chan of selling sunglasses to the black market to boost sales.

A Business Week investigation showed that this was not an isolated case. The executives claimed that Daniel E. Gill, chairman and chief executive officer of B&L, drove demand for achieving a double-digit annual profit growth. The managers funneled glasses into the black market, were promised to give long-term payments to customers, and even threatened the distributors to take on big quantities of unwanted products or they would cut them off as their distributors. Other divisions sent goods to the customers before they ordered them and booked the shipments as sales.

One of the former managers, according to Business Week, claimed that the signals sent from the top led to cutting corners. The company’s compensation plan was also a menace to the employees. Finally, the problems appeared internally and forced the company and its executives to produce profits for them from the managers of the divisions. It was not the customers who wanted more products, it was the executives in charge who were looking out only for themselves and their profits. The managers did not care what problems their “cut corners” would create; they only wanted to keep their jobs and would do anything to ensure profits.

Source: Maremont, M. (1995). “Blind Ambition: How the Pursuit of Results Got Out of Hand at Bausch and Lomb.” Business Week, October 23, pp. 78–92.