Contemporary Multicultural Behavior

The unexamined scientific analysis of multiculturalism can be viewed as an ignorant castle that imprisons a manager within his or her perceptions.

When you have read this chapter you should be able to understand human behavior through:

three branches of the common body of knowledge: philosophy, science, and technology,

indication of the principle concerns of philosophical inquiries,

indication of the scientific concerns of human behavior, and

illustration of the technological effectiveness on human behavior.

People’s behavior can be studied through application of natural, social, and behavioral sciences, philosophy, and informational technology. In a general traditional view, the basic academic integration of anthropology, sociology, and psychology and their rigorous research approaches made excellent contributions to the emergence of a new subacademic and cross-fertilized knowledge—namely behavioral culturalogy. Such a diffusive and integrated body of knowledge can be applied for better understanding of peoples’ relations and behavior in the newly global environments of international business.

This chapter will begin with a review of the required body of knowledge in the field of behavioral culturalogy. By defining the terms, functions, and approaches of culturalogy, you will be familiar with different beliefs and value systems in the field of international business. This chapter offers a very in-depth and broad scientific, behavioral, and cultural studies discussion which should establish a new look at today’s multinational and multicultural organizations.

In this chapter, you will learn how to apply scientific theories for finding multicultural similarities and differences in a multinational physical environment. The definition of each branch of knowledge will allow you to understand an explanation of the relationship among scientific, technological, philosophical, and artistic understanding of cultural behavior. A discussion of the typology of a holistic knowledge illustrates how cultural behavior in home and host countries could improve a multinational corporation’s operational capabilities.

The New Field of Behavioral Culturalogy

Traditional scientific management, bureaucracy, human relations, organizational behavior, system theories, and other approaches are valid theories to some extent to be applied in domestic organizational problem solving. Those theories have taken heuristic, cognitive, behavioristic, pragmatic, and humanistic approaches for modeling organizational behavioral decision making. However, none of the above management theories paid special attention to the application of behavioral culturalogy in their hypothetical theorization as a new form of problem solving.

Today, the emergence of cultural behavioral variables and their consequential effects in multinational and multicultural organizations have drastically changed managerial decision-making processes. Behavioral culturalogy within the context of the international free market economy is a new field of inquiry and needs to be applied and directed synergistically for positive outcomes.

The scientific application of behavioral culturalogy is critical to the goal achievement of multinational and multicultural organizations. Multinational managers should be familiar with cultural philosophy and medical symptomalogy of both home and host countries. The use of the behavioral culturalogical approach is an interdisciplinary holistic knowledge that applies philosophical, social, behavioral, and natural sciences, and technological information in international problem solving. Application of the behavioral culturalogical approach can directly help managers better understand, predict, and direct the international expected behavior of international producers and consumers (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Holistic Interdisciplinary Relationships Between Academic Philosophy, Sciences, and Technology

Source: Part I adapted from Weber, C. O. (1960). Basic Philosophies of Education. New York: Holt, Rhinehart, and Winston: 12.

Intercultural Contact: Processes and Outcomes

For more than a century, most management approaches ignored traditional beliefs and values of peoples and purely neglected the crucial effects of humanities, philosophy, religion, and other cultural perceptions within the workplace. For such a crucial shortfall, after briefing an overview on definition and application of philosophical, natural, social, and behavioral sciences, and technology, a general approach in multinational behavioral management has been provided in this chapter.

Intercultural contact among individuals has an ancient history, and cross-cultural interchange among nations is as old as recorded history. Historically, people traveled to other lands to settle or conquer, trade, convert, teach, and learn. Cohn (1979: 18) has identified various motives for cross-cultural contacts among individuals. He has found five modes of contacts: recreational, diversionary, experiential, experimental, and existential. Indeed, probably the best accounts of both intercultural and cross-cultural contacts come from interdisciplinary social scientists, novelists, playwrights, and philosophers.

Perhaps the most important question in multinational corporations is: What is the main philosophy behind intercultural and cross-cultural contacts? The answer is fairly easy: to discover potential opportunities for the exploitation of those markets. Other reasons in conjunction have been identified partly due to a shrinking world as a result of the jetliner and silicon-chip age, but largely also due to governmental intervention. For example, American expatriate managers who move abroad and back again to the United States are simply motivated by economic rewards. However, Torbiorn (1982) found in his study of Swedish business persons that motives and behaviors were much more complex. He found both “push motives” relating to dissatisfaction and “pull motives” relating to a belief in increased satisfaction being associated with the move. “Pull motives” included a special interest in the particular host country, increased promotion prospects, wider career opportunities, or generally more favorable economic gain. “Push motives” included negative rather than positive, and lesser rather than greater, freedom in choosing the host country. Such motives were associated with lower levels of adaptation and satisfaction.

Today, the universality of behavioral culturalogical approach indicates that preferred levels and modes of need-perception in all cultures are not the same. However, the ingredients of the modes of need perceptions are similar in all cultures. For example, let us start with the appeal of nudity in international advertising. The fascinating motive is not how much sex there is in international advertising. Contrary to cultural impressions, sexual appeals in advertising may be viewed as a sinful and/or unethical and immoral act in one culture and a joyful, praising, and/or legal act in another culture. Table 4.1 identifies intercultural and cross-cultural similarities and differences in American, Australian, Asian, and Middle Eastern cultural advertising perceptions and beliefs in nudity.

Table 4.1. Nudity’s Cultural Appeal in Advertising

* Fowles, J. (1995). “Advertising’s Fifteen Basic Appeals.” In Petracca, M. F. and Sorapure, M. (Eds.), Common Culture: Reading and Writing About American Popular Culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, p. 64.

Englehart and Carnally (1997: 37) indicate that:

Cross-cultural variation does not simply reflect the changes linked with modernization and post modernization processes: … each society works out its history in its own unique fashion, influenced by the culture, leaders, institutions, climate, geography, situation-specific events, and other unique elements that make up its own distinctive heritage.

While there may be several ways of classifying the importance of these unique cross-cultural characteristics, each society maintains its own uniqueness.

The importance of cultural orientation of people toward individuals’ existence and sociocultural and psychological needs plays an important role in shaping their cultural perceptions. In cross-cultural studies, we need to identify the prioritized similar and dissimilar needs of people in both home and host countries.

In cross-cultural study one particular list of fifteen needs has proven to be especially valuable. Fowles (1995: 61) has indicated in his research these needs as:

The need for sex

The need for affiliation

The need to nurture

The need for guidance

The need to egress

The need to achieve

The need to dominate

The need for prominence

The need for attention

The need for autonomy

The need to escape

The need to feel safe

The need for aesthetic sensations

The need to satisfy curiosity

Physiological needs: food, drink, sleep, etc.

To understand the importance of these needs, we need to understand not only the people themselves but also their cultural orientation and environmental conditions. Except for the physiological needs, the other fourteen needs are learned through cultural orientation. To do research in cross-culturalogy we need to identify six methods of knowledge.

Six Theories of Behavioral Culturalogical Knowledge

There are six theories of understanding things: revelation, coherence, presentative, representative, pragmatic, and intuition (Weber, 1960: 13–14).

The Revelation Theory

“This view holds that the final test of the truth of assertions is their consonance with the revelations of authority” (Weber, 1960: 13).

For example, when John H. Sununu was governor of New Hampshire (1983–1987), he greatly increased his expert credibility by taking sole control of the computer system that kept track of the state’s finances (Van Fleet, 1991: 185).

The Coherence Theory

“This theory says that a statement is true if it is consistent with other statements accepted as true” (Weber, 1960: 13).

For example, when Robert J. Eaton took the position of CEO replacing Chrysler’s “Mr. Charisma,” Lee Iacocca, he believed in quantifiable short-term profits. Such a view is also being articulated by CEOs at Apple Computer, IBM, Aetna Life and Casuality, and General Motors (Robbins, 1998: 391).

The Presentative Theory

“This view holds that reality as presented to the mind in perception is known directly and without alteration. Errors of perceptions occur, but further observation is able to detect and explain them” (Weber, 1960: 13).

For example, on April 23,1985, Roberto C. Goizueta, chairman of Coca-Cola, made a momentous announcement: “The best has been made ever better,” he proclaimed. After ninety-nine years, the Coca-Cola Company had decided to abandon its original formula in favor of a sweeter variation, presumably an improved taste, which was named “New Coke.” On that date, the chairman made an intercultural strategic decision to change the taste of Coca-Cola and within twenty-four hours, 81 percent of the U.S. population knew of the change (Demott, 1985: 55). Early results looked good; 150 million people tried New Coke. The decision looked unassailable, but not for long. On July 11, 1985, the top executive appeared on the stage in front of the Coca-Cola logo to announce that two types of Coke were available: (1) for those who were drinking New Coke and enjoying it, and (2) for those who wanted the original Coke. The message was that “we heard you,” and the original taste of Coke was back. Despite $4 million and two years’ research, the company had made a major miscalculation and “New Coke” became Coke in 1992. The original Coke is called Coca-Cola Classic (Hartley, 1998: 160).

The Representative Theory

“This view, again favored by certain realists, holds that our perceptions of objects are not identical with them. This differs from the presentative view sketched above which states that when we perceive truly, our perception is identical with the object perceived. This implies that the object perceived literally enters the mind which perceives it—a rather startling conclusion. The representative realist tries to be more cautious on this point. What we see when we look at a tree is only its image. The tree cannot be identical with this image. The image is in one’s mind, and the mind is somehow located in the brain; if the tree is fifty feet high, there is not enough room (physically) in one’s brain to accommodate it” (Weber, 1960: 14).

For example, researchers have introduced the idea of culture distance to account for the amount of distress experienced by a student from one culture studying in another. Babiker, Cox, and Miller (1980: 109) hypothesized that the degree of alienation, estrangement, and concomitant psychological distress was a function of distance between the student’s own culture and the host culture. Also, Furnham and Bochner (1982) conducted a similar study and found that the degree of difficulty experienced by sojourners in negotiating everyday encounters is directly related to the disparity (or culture distance) between the sojourners’ culture and the host society.

The Pragmatic Theory

“This view holds that statements are true if they work successfully in practice. If an idea or principle is effective in organizing knowledge or in the practical affairs of life then it is true” (Weber, 1960: 14).

For a society to continue over time it is imperative that it works out systematic traditional value systems for mating, childbearing, and education. If it fails to be regulated, it will die in a very short time. Some societies permit random mating and others have rules for determining who can marry, under what conditions, and according to what traditions. All societies around the world have patterned systems of marriage (Ferraro: 1994: 25).

For example, there are three pragmatic different legal systems concerning marriage: “common law,” in England; “code law” in France; and “Sharia law” in Middle Eastern countries. “Common law” refers to that practical part of the law that grew up without benefit of legislation and resulted from court decisions. These rulings then in their pragmatic term became the precedent for subsequent litigation (Pegrum, 1959: 21) (e.g., in the United States a couple who have been living together for many years without church and/or governmental documentation could be considered by law as married). The code law refers to the body of laws of a state or a nation regulating ordinary private matters (e.g., in France, a mandatory marriage performed and documented by a government official rather than by a member of the clergy is upheld as legal marriage). The “Sharia law” refers to the traditional religious law which is upheld by both the state and the church through Moslem scripture (e.g., in the Middle Eastern cultures, men officially can marry four women either by law and/or by the Mollah or Ayatollah. However, men can marry many women on a temporary basis by following neither the state nor the church. This type of marriage is upheld by law and by the church, because it is an agreement between two adult people).

The Intuition Theory

“This view varies so much in its definition that it sometimes becomes identical with some of the other theories … At one extreme, intuition refers to a mysterious and immediate inner source of knowledge apart from both perceptual observation and reasoning…. At the other extreme the term intuition has been used to designate generally accredited and immediate ways of knowing, such as immediate sensation, or the immediate awareness we may have of self-evident or axiomatic truth.” (Weber, 1960: 14)

The U.S. economy is a commercial-exchanging economy based on the system of free enterprise (free entry and free competition) (Cohen, 1995: 5). By his intuitive efforts, forty-five-year-old William H. Gates III became the richest man in America, and Microsoft and its leader made over $7 billion within two decades. It should be noted that William H. Gates III was a college dropout. In 1974 at age eighteen, he and his friend Paul Allen established a small company in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and developed software for the Altair, the first personal computer. Yoder (1992), in The Wall Street Journal, described: “The generational shift in the computer industry is unfolding… . As leadership slips away from the old behemoth … it is being picked up by two young juggernauts—Intel Corp. and Microsoft Corp.—which both were nurtured by IBM.”

Knowledge-Based Integration of Philosophy, Sciences, Arts, and Technological Information

Behavioral culturalogical approach is relying on synergistic knowledge-based integration of philosophy, technology, arts, and sciences. The main reason for applying the interdisciplinary approach in multicultural behavior is based on a holistic view of the concept of peoples’ culture, which includes all human-made knowledge. Among some of the special features of multicultural behaviorism that contribute to multinational organizations are: active participatory observation, the emic view on cultural values, the fundamental value orientation of cultural concession, the synergistic behavioral end results, and holistic cultural relativism.

The behavioral culturalogical approach holds that organizational behavior is essentially universal. Labor forces and customers around the globe, particularly in the United States, are becoming more diverse in terms of national origin, race, religion, gender, predominant age categories, and personal preferences.

With a fair viewing on global cultures, certain features have been initiated originally in one or several parts of the world independently and then spread through the process of diffusion to other cultures. The congruence theory of managerial knowledge holds that the crucial test of reality concerning the universal nature of human behavior in the workplace is the degree of harmony between employer-employee propositions regarded as true. Such a global mandate urges multinational corporations to strive for establishing multilingual and multicultural management systems.

The world is shrinking rapidly. Multinational corporate assignments are becoming a standard part of a well-rounded business. Cross-cultural understanding and behavioral skills are a necessity. As a result, the traditional management knowledge, which has been highly fragmented and incomplete, is not effective anymore. With an eye toward educating tomorrow’s global managers, we need to think and behave globally.

Today, multinational organizations are faced with unsolved potential problems and issues based mainly on the misunderstanding of multicultural value systems. It is necessary to move from tolerance to appreciation when managing multicultural organizations. The main challenge of today’s and especially tomorrow’s managers is to be aware of specific multicultural changes, along with the factors contributing to the organizational synergy.

In such a domain of inquiry, the main question is: what about human behavior within multicultural environments? The answer is very complex. This complexity can provide multicultural synergy, because when values are synthesizing and emerging in a new favorable condition, the end result will be synergy. Multicultural synergy sometimes can be demonstrated by the mathematical analogy that 2 + 2 = 5 instead of 4. If the multicultural synergy is beyond the sum of the total parts, then positive synergy has occurred (Weber, 1960: 113; Moran and Harris: 1982: 5). However, given the various cross-cultural barriers and cultural deficiencies, the end result may be represented by the equation 2 + 2 = 3, if the sum is below the total parts. This will illustrate that the organizational incumbents are in conflict.

Philosophy

Philosophy is the basic foundation for conceptual understanding of human life by the examination of cause and effect of existence. In traditional conception, philosophy endeavors to integrate all human knowledge. Inquiries such as the following domains of knowledge have shaped philosophy:

Was there a beginning of time?

Will there be an end to time?

Is the universe infinite or does it have boundaries?

Is the universe expanding or is it shrinking?

Or could it be both infinite and without boundaries?

On viewing these conceptions and others, the current problems of philosophers still relate to three areas of inquiry: metaphysics, epistemology, and axiology. Thus, philosophy is the integration of all human knowledge and erects a systematic view on the nature and the place of human beings in it. In an attempt to study multicultural behavior of different groups of people, we should try to understand the three above modes of arriving at knowledge.

Metaphysics

This concerns issues on the nature of reality and humanity’s place within it. What is the matter in its essence, and how does it form the vast material cosmos ordered in time and place (cosmology)? What is the essential nature of the mind and/or soul? What about the existence and the nature of a superpower—God (theologically)? What does it mean to exist? What is the criterion for existing (ontology)? (Ontology refers to knowledge of the nature of the world around us.) What are the ultimate causes of things being what they are (causalogy)?

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a scientific manner of thinking that considers things as phenomena. It is a kind of knowledge that reveals a fact, occurrence, or circumstance observed or observable that impresses the observer as extraordinary phenomena. Phenomenology describes values of remarkable things or persons through scientific appearance or immediate intuitive objective of awareness in the human mind. Phenomenology is a qualitative conceptual awareness which can be manifested constructively by quantitative value judgments in the human mind. Rational decision-making processes in the field of business consist essentially of using certain axioms or assumptions, stated as principles of applicability of successful experiences and knowledge of the world of business experience.

Epistemology

Espistemology has to do with the problem of knowledge: We have knowledge. How is this possible? What does knowledge mean? Can all knowledge be traced to the greatest gateways of our senses—to the senses plus activity of reasoning, or to the means and ends of reasoning? Do feelings render wordless but true knowledge? Does true knowledge ever come in the form of immediate intuition? How can we identify different branches of knowledge?

Axiology

Axiology is concerned with the problems of value. There are three main traditional fields of value inquiries: (1) morality, (2) ethics, and (3) aesthetics.

Morality. The term “moral” is derived from the Latin word Mores. In The Oxford English Dictionary (1963) “moral” means “habits in life in regard to right and wrong conduct,” or “Of or pertaining to character or disposition, considered as good or bad, virtuous or vicious; of or pertaining to the distinction between right and wrong, or good and evil, in relation to the actions, volitions, or character of responsible beings.” In an etymological sense, it means “pertaining to the individual’s manner and custom of judgments.” Morality is the term used to manifest the individual’s virtue. Morality also has to do with an individual’s character and the type of behaviors that emanate from that valuable character. Virtue refers to the excellence of intellect and wisdom. Morality’s end result, through intellectual truthfulness, righteousness, and goodness of thoughts and conducts, is happiness. Conscience is a base for moral acts. It is the ability to reason about self-conduct, together with a set of values, feelings, and dispositions to do or to avoid conceiving and perceiving actions. If morality is viewed as telling the whole truth, then amorality is telling a partial truth. Each individual is morally obligated to develop an objectively correct conscience; but their own usually is obligated to behave in accordance with his/her conscience. Failure to fulfill one’s self moral commitment can lead not only to blame and shame, but also to remorse (De George, 1995: 119).

Ethics. The term ethics is derived from the Greek word ethos. Ethos means the genius of an institution or system. Also, it refers to the science of morals and the department of study concerned with the principles of human duty. Ethics concerns itself with human societal conduct, activity, and behavior, which are manifested through knowledge and deliberated behavior. Ethics is the collective societal conscious awareness of a group of people. Ethic’s end results, through societal conscious understanding of fairness, justness, and worthiness, can lead human beings toward social justice and peaceful behavior.

Aesthetics. Of particular interest to human concepts are the formal aspects of art, color, and form, because of the symbolic meanings they convey. Aesthetics pertains to a culture’s sense of beauty and good taste and is expressed in arts, drama, music, folklore, and dance (Ball and McCulloch Jr., 1988, p. 269). It is the reflection of the human expression in humanities: arts, music, dance, movies, and theatrical drama. Of particular interest to multicultural behaviorism is the artistic combination of humanities: arts, colors, and forms specifically in exhibitor conceptions and perceptions; because each group conveys symbolic meanings and values in humanity’s cultural tastes.

Humanities. Humanities are those branches of knowledge concerned with human thoughts and culture. Humanities have primarily a cultural character and usually include languages, literature, and arts.

Arts. Arts are the productions or expressions of what is beautiful, appealing, and/or of what is more than of ordinary significance. Arts are the establishment of human unity in variety, similarity, proximity, and connectivity in bounded perceptions. Arts are expository, detailed modes of creativity of novel things. Arts manifest compositions of an individual and/or a group of human beings’ emotional, sensational feelings and thoughts to explain or manifest something in specific causal forms.

Artists manifest the interrelations, tendencies, and/or values of human beings with their environments. Such behavioral modes represent the interpretation of cultural facts, conditions, concepts, theories, beliefs, and relationships between the individual’s diametrical conception and the cultural circumferences of the human life cycle. Arts try to explain humanity’s inner motivations at a particular time and place.

Music and dance. Music is the art of sound in time that expresses ideas and emotions in significant forms through the elements of rhythm, melody, harmony, and color. Dances are the rhythmic movement of one’s feet, body, or both in a pattern of steps.

Movies and theatrical drama. Movies, or motion pictures, are a genre of art or entertainment. Movies are selling specific motion pictures of kissing, ideas, body movements, fashion, sex, history, political ideologies, sociocultural values, and industrial lifestyles. (Parhizgar, 1996:309)

Sciences

Science deals with human understanding concerning the discovery and formulation of the real world in which inherent properties of space, matter, energy, and their interactions can be perfectly scrutinized. Science is a rational convention related to the generalization of environmental norms, expectations, and values. It is nothing more than the search for understanding the real world. In a general term, we can define science as simply the empirical process forming the generalized inquiry by which viable understanding is obtained. In the field of scientific inquiry, a scientist uses analytical scientific methodologies to discover valuable alternatives for generalized problem solving techniques. Therefore, scientific findings are reliable and validated to further problem-solving alternatives. For a scientist, mathematics is a tool for building models and theories that can describe and eventually explain the operation of the world—be it of the world of material objects (physics and chemistry), of living things (biology), of human beings (social or behavioral sciences), of the human mind (cognitive science), or of human truthfulness, justness, and fairness (cognititive science). Therefore, science is the manifestation of positivistic conception of inquiry and has provided an acceptable understanding of nature. The distinction between science (normal science) and nonscience or quasi-science (pseudoscience) is therefore blurred.

Berelson and Steiner (1964: 16–17) indicate that organizational behavioral researchers strive to attain the following hallmarks of science:

The procedures are public.

The definitions are precise.

The data collecting is objective.

The findings are replicable.

The approach is systematic and cumulative.

The purposes are explanation, understanding, and prediction.

Taxonomy of Sciences

Acquisition of knowledge refers to individual perceptual and practical capabilities which typically take in information via the senses through scientific methodology. They are most comfortable when containing the details of any feasible situation in a quantified understanding process. Sciences generally can be classified into four major categories:

Observational sciences

Natural sciences

Social sciences

Behavioral sciences

Observational Sciences

Observational sciences include astronomy, geology, physics, and chemistry. The primary aim of these sciences is to discover a cause-and-effect relationship between material things. The observational sciences offer the best possibility of accomplishing this goal simply through manipulation of independent variables, to measure their effect on or the change in the dependent variables.

Natural Sciences

Natural sciences include zoology (animals), botany (plants), protistology (one-celled organisms), biorheology (deformation and deterioration), and biology (physiology, microbiology, immunology, ecology and evolution, and molecular and cellular biology). Natural sciences identify real characteristics of causes, functions, and structures of all material things.

Biology concentrates on the study of all living things, examining such topics as the origins, structures, functions, productions, reproductions, growth, development, behavior, and evolution of different organisms. For an international manager, familiarity with both biological and ecological conditions of the workplace is a must. In most cases, both endemic and epidemic diseases are the most organizationally interruptive problems in multinational organizations. Many organizations annually lose a portion of their budget because of tardiness and absenteeism.

Social Sciences

Social sciences include economics, political sciences, demography, history, and geography. Economics is the study of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Social scientists concern themselves with the areas of the labor market, capital intensity, synergistic dynamic of human resources planning and forecasting, accessibility, scarcity, and suitability of productive resources, as well as assessment of profitability concerning economic development and growth through cost-benefit analysis.

The mainstream of thought of modern civilized societies through history concerns power, politics, people, and public policy. Politics in all societies is a fact which has made our modern life very complex and has been defined in a number of ways. Politics is considered to be the fundamental concern in today’s international diplomacy (Parhizgar, 1994: 110). A common theme of politics is exercising influence through exertion of power (Meyes and Allen, 1977: 672–678). Politics is the study of diplomatic behavior: decision making, conflict resolution, focusing on interest objectives of groups, coalition formation, preservation of classes of power, power distance, and rulership.

Demography is the science of biostatistics and quantitative statistics of populations, including records of births, deaths, diseases, marriages, numbers, means, percentages, all both material and nonmaterial value systems, etc.

History is a branch of scientific analytic knowledge dealing with past events. It is a continuous, systematic narrative of the chronological order of past characteristics of human civilizations as relating to a particular people, country, period, and/or person.

Geography is the science dealing with the real differentiation of the earth’s surface, as shown in the character, arrangement, and interrelations over the world of such elements as climate, elevation, soil, vegetation, population density, land use, industries, or states.

Behavioral Sciences

Behavioral sciences include anthropology (physical anthropology, cultural anthropology, archaeology, anthropological linguistics, and ethnology/ethnography), sociology, and psychology.

Anthropology is the science of humankind, literally defined as the science of human generations with the interactions between generations and environments, particularly cultural environments. Cultural anthropology deals with convinced learned behavior through cultural orientation as influenced by people’s cultures and vice versa. In a general form and term, cultural anthropology studies the origins and history of humanity: their evolution, development, and the structure and functioning of human cultures in every place and time. Since the definition of a total culture is usually beyond the scope of a single specialist, anthropologists have developed specialization of this science into: psychological anthropology, economic anthropology, urban anthropology, educational anthropology, medical anthropology, rural anthropology, and applied anthropology. In sum, as Harvey and Allard (1995: 11) indicate, “An anthropologist takes the role of an observer from a culture more developed than our own and describes features of our civilization in the same manner as we describe cultures we view as primitive.”

Cultural anthropology studies the origins and the history of human cultures, their creation, evolution, development, structure, and their interactive functions in every place and time (Beals and Hijer, 1959: 9).

Physical anthropology is the study of the human condition from a biological perspective. Essentially, it is concerned with restructuring the evolutionary record of the human species and dealing with how and why the physical traits of contemporary human populations vary across the world.

Cultural anthropology deals with the study of specific contemporary cultures (ethnography) and with more general underlying patterns of human culture derived through cultural comparison (ethnology). Cultural anthropologists provide insights into such questions as: How have traditions, habits, orientations, and customs relating to a group of people emerged? How are marriage customs and kinship systems operated? In what ways do people believe in supernatural power? How do migration and urbanization affect each other?

Archaeology is the study of the lifestyles of people from the past through excavating and analyzing the material remains of past human life and activities. Archaeologists reconstruct the cultures of people who are no longer living. Archaeologists deal mainly with three basic components of culture: material culture, ideas, and behavior patterns.

Anthropological linguistics is the study of human speech and language. This branch of knowledge is divided into four distinctive branches: historical linguistics, sociolinguistics, descriptive linguistics, and ethnolinguistics.

Sociology is traditionally defined as the science of society, for searching for and solving social problems within the context of its dynamic processes, purposes, and goals. Sociology is the science of human groups and is characterized by rigorous methodology with an empirical emphasis and conceptual consciousness (Luthans, 1985: 36). Sociology is also the study of social systems such as families, occupational classes, and organizations. The overall focus of sociology is on social behavior in societies, institutional behavioral patterns, organizational structures, and group dynamics.

Psychology has been defined as the science of human and animal behavior. Psychologists study the behavior of human beings and their perceptions in both industrial and/or agricultural organizational ecology. Psychologists also study the behavior of people in organizational settings. There are many formative schools of thought in the field of psychology. The most widely known are structuralism, functionalism, behaviorism, gestalt psychology, and psychoanalysis.

Structuralism was founded by Wilhelm Wundt in 1879 in Germany. He had established a laboratory for studying human psychology. The theory revolved around conscious experience and attempted to build the science of mind. This theory applies to a structural breakdown of the human mind into units of mental states such as sensation, memory, imagery, and feelings.

Functionalism was developed in America by William James (1842–1910) and John Dewey (1859–1952). This theory of psychology is based upon the function of mind. Emphasis is placed mainly on a human’s adaptation and adjustment to his or her ecological environment. This theory of the mind emphasizes human sensory experience such as: learning, forgetting, motivation, and adaptability to a new situation. Morgan and King (1966: 22) state that: “Functionalism had two chief characteristics; the study of the total behavior and experience of an individual, and an interest in the adaptive functions served by the things an individual does.”

The foundation of the behaviorism theory is based upon the connectivity of the human mind toward behavior. Behaviorism was influenced by the Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936). Since the structuralists were concerned only with the mind, and functionalists emphasized both mind and behavior, behaviorists focused on consequential results of such a connectivity in relations with observance, objective behavior, and the significant outcomes of human mind and body movements.

Gestalt psychology or synergism was founded by Max Wertheimer (1880–1943) around 1912. The term gestalt roughly means form, whole, configuration, organization, or essence. Gestalt psychology maintained that psychological understanding could be understood only when viewed as organized and structured phenomena as wholes and not broken down into primitive perceptual elements (by introspective analysis) (Zimbardo, 1992: 267). For example, the Muller-Lyer illusion, which follows, shows that by human perception, the two lines X and Y are of equal length. However, because of the kinesthetic perception of the human mind in relation to the total ecological environment of the surroundings, the lines are perceived to be unequal because of their relationships to the whole.

![]()

The Muller-Lyer Illusion

In other words, the whole is perceived differently from the way the sum of parts would be perceived. However, according to Euclidean geometry (surface geometry) both lines X and Y are equal; according to spherical geometry, X seems greater than Y, because of the illusion of human beings to which it seems the line X has occupied more space than the line Y.

Psychoanalysis psychology has come from Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). His theory is about unconscious motivation, the development and structure of personality, and his treatment techniques.

Social psychology is academically interdisciplinary. It consists of an eclectic mixture of sciences and arts (Luthans, 1985, pp. 30–38). Social psychology is generally a synthesized scientific theory of psychology and sociology. If social psychology emphasizes individual behavior, its close tie is with psychology. Also, it is equated with behavioral science. From the standpoint of emphasis on sociology, social psychology is the study of individual behavior within relation to groups (group emphasis).

Behavioral Sciences and Research Perspectives

Historically, scientific multicultural behavior emerged from the concept of human beings considering a variety of cultural value systems to enhance their living styles. Multiculturalism perceives the world as a whole and that the utility of consumerable things is the essence of cultural experiences. Nevertheless, human perception has been very egocentric and ethnocentric. Each individual and group regards the world from their own standpoint of personal values and the kinship of the individual’s and/or group’s interests.

In recent years, it has become commonplace for one discipline to borrow terminologies and models of research from another. Multifunctional, biological, mechanical, ecological, and cross-boundary divisional frameworks have caused the urgency to accelerate the emerging path of new scientific endeavors in all aspects of human behavioral knowledge.

The new visionary conception of an international market economy and diplomacy has been viewed to support the position that international management should rely on development of psychological and physiological characteristics of human adaptability and loyalty. The technopsychological mentality of the twenty-first century will focus on international multicultural behavior. This new dimension has similarly spanned across and germinated in disciplines such as the political sciences, military sciences, and ecological sciences.

In the field of management and other social sciences, new multidisciplinary sciences have been used long before: the models we refer to in this text are the highlights of all social sciences, humanities, philosophies, and technologies. The model of multicultural behavior is not a simple one. As Moran and Harris (1982: 5) indicate: “In multinational organizational development, they have used a list of ethnocentric, polycentric, regiocentric and geocentric as four orientations toward the organization behavior. Within the internal organizational behavior, there are too many complexities with application of these models.”

As a result of international diplomacy, super-technomilitary interventions, multinational commercial transactions, and multicultural understandings all have made human behavior more difficult and more complex than ever. Consequently, international cross-culturalizational behavior could be best described as multidisciplinary, rather than interdisciplinary.

As mentioned earlier, all multicultural behavioral models discussed so far depend upon a rigorous research methodology in order to better understand human cultural and multicultural behavior. This search for why humans behave the way they do is based upon their conceptions, perceptions, values, attitudes, beliefs, ideologies, faiths, social influences, and leadership. As these topics indicate, multicultural behavior can be studied interdisciplinarily through all bodies of knowledge. In fact, the magnitude of multiculturalism is so broad that researchers, scholars, philosophers, and technologists argue that there can be no precise scientific direction for studying multicultural behavior.

Technology

Terpstra and David (1991: 136), through a broad anthropological sense, state that:

Technology is a cultural system concerned with the relationships between humans and their natural environment. A society is well adapted to its environment when its technological system is: (1) environmentally feasible in that it produces a livelihood for inhabitants without depleting the natural resources; (2) stable in that it can respond to temporary natural disturbances such as droughts, storms, and epidemics; (3) resilient in that it can return to a normal state of operations after a natural disturbance; and (4) open to revision when a natural disturbance reveals its inherent shortcomings.

Behavioral Culturalogical Framework

Behavioral culturalogy is very young but has the advantage of growing very quickly. It establishes a synergized framework for human thoughts and actions. Consequently, with the “new world order,” all traditional organizational behavioral approaches seem to be in a dilemma. Why? Because searching for a popular theoretical orientation has not solved human conflicts within a culture and/or among cultures.

The two fundamental differences between national and international cultures are geographic dispersion and multicultural conception in terms of assimilation and integration. National cultural boundaries delineate the sociocultural values, political-legal ideologies, and economic systems within geographic boundaries of nations. It is within and beyond these geographical and/or political cultural boundaries that multinational and multicultural organizations must operate. Multiculturalism is the normal experience of most individuals in the borderless information systems in academia, for they are perforce drawn into the microculture of administrators, teachers, physicians, and others who have power over them.

Fatehi (1996: 153) indicates that: “While a domestic firm embodies the basic attributes of its national culture, a multinational company is influenced by the multicultural nature of their global environment.” Each multinational organization perceives its own culture as a system of shared meaning among members. Organizational theorists now acknowledge that cultural institutionalization is a relatively recent phenomenon. However, in a domestic organization, the origin of cultural philosophy is viewed as an independent variable affecting an employee’s attitudes and behavior. It can be traced back fifty years to the notion of institutionalization (Selznick, 1948: 25). Interestingly, institutionalization of a cultural framework in an organization takes on a life of its own, apart from any of its members, and acquires immortality.

A framework of scientific-based knowledge of traditional behavioral sciences and their research methods, with a breadth of viewing on today’s international behavior spectrum, is a prerequisite for comprehending a diverse modality of knowledge. A diverse behavioral modality of knowledge is what separates the traditional scientific organizational behavior approaches from the complex multi-institutional behavioral approaches such as multi-culturalization, cross-culturalization, acculturalization, enculturalization, and parochialization. Although the domain of multi-institutional cultural behavior is very wide and possesses different approaches, through scientific analysis it identifies many inherent dynamic causes and effects. Therefore, those approaches will be defined to avoid many encountered difficulties in multinational organizations.

Demographic mobility, such as tourism and individual migration particularly, have been the major causes of thinking and dealing with cross-cultural and multicultural issues. The conditions of circumstances—socioeconomic, political, religious, ethical, and educational ones — can cause people to leave their motherlands and immigrate to other countries. Then, these immigrants must be institutionalized with the new cultural environments. In such a reciprocal orientation, we can find six different processes of cultural institutionalization: (1) multiculturalization, (2) cross-culturalization, (3) parochialization, (4) enculturalization, (5) acculturalization, and (6) biculturalization. Through these forms, people must cross their national cultural boundaries and be familiar with their host countries’ cultures. Therefore, behavioral culturalogy identifies how people in different cultures can identify and understand their own and others’ cultural similarities and differences. For example, American culture has multiple subcultures because of its great diversity and its strong emphasis on individualism, democracy, and freedom as a cherished valuable institutionalized culture. Individualism encourages development of idiosyncratic belief systems. However, democracy encourages like-minded individuals to band together to express similar concerns and further their beliefs in all sectors of societal life (Trice and Beyer, 1993).

Multiculturalization

The term multiculturalization is submaximization of diversified cultures. Historically, since the 1960s, the term multiculturalization has been an umbrella for the inclusion of several social and intellectual cultural movements around the world. It shares inclusive ideas that most often refer to pluralism. The different ethnic groups that have changed over time include: blacks or African Americans; Native Americans or American Indians; Hispanics, Latino s/Latinas, Chicanos/Chicanas, and Puerto Ricans; Asian Americans or American Orientals; and others. Parallel to the growth of such a notion in American culture there has been the growth of feminist or gender groups too.

In terms of multiculturalization, a controversial issue surrounds the traditional arguments for the existence of a major culture in a society. It is argued that even in applicability of a specific value of a major culture within a contextual vision of a national cultural boundary, it could not predict harmony within diversified majority and minority ethnic groups. Actually, in all cultures, women’s cultures or feminist cultures have been perceived as minority cultures. Although women are in the majority demographically, they do not have the sociopolitical position of power to enable them to stabilize their actual cultural majority of feminism. Moreover, if in all cultures women are a majority, they are a majority whose members belong to every culture and subculture. As a result, women have both areas of community and divergence, both of which are reflected. Also, other controversial issues are the traditional epistemological arguments that our international cultural value systems would recognize multiversities under a single general term of multiculturalism. The same holds true of traditional arguments concerning the philosophy of language, that universal and international are the immediate semantical values of predicates of meanings and thoughts. Such controversial issues and perceptions have led many philosophers and scientists to believe that the surest argument for the existence of a universal culture has come from the cognitive perception of virtual beauty in relationship to artificial and real beauties. So, even the arguments are successful when they indicate that the doctrines of all cultural professional philosophies exist independently of each culture. The major reasoning is that all universal cultural value systems are uniquely suited to carry certain kinds of modal national information and traditional perceptions in their imaginative superiority.

As a terminological modeling of thoughts and reasons, multiculturalization could be used for propositions as well as for propensities and relatedness. Such an argument applies against conditional nominalism (the doctrine that universals are reducible to names without any objective existence corresponding to them), and also against conceptualism (the doctrine that concepts enable the mind to grasp objective reality, which is midway between nominalism and realism) in terms of realism.

Multiculturalism in multinational corporations means the inclusion of all distinguishable parts of cultural values and beliefs of both home and host countries which could be labeled universal. If we believe in multicultural synergies, then the arguments of majority and minority will not be used because the emphasis is on the need for a unified intuitionism (the ethical doctrine that virtue is based on usefulness of thoughts rather than beauty of physical bodies). Recognition of universal values asserts that the statement of international beliefs is a synergistic phenomenon which can provide harmony and peace among people.

By reviewing the literature, even some of the nominalist, conceptualist, and realist scholars have tended to neglect this notion that multiculturalism should have the inclusion of all large cultural value systems within the contextual boundary of a multinational organization. By this token, multiculturalism is the inclusion of all similar values that are universal and uniquely suited to carry a certain kind of international value proposition. Then, the urgency within a universal conceptual vision is based upon international terms and meanings of multicultural value systems, which will be acceptable for all nations.

It is a factual assumption that through virtual beauty of multicultural value systems, multinational corporations can achieve the meaning of synergistic existence. In synergistic terms, all phenomena that exist in human cognitive perceptions are viewed as holistic realities that exist. Since human perceptions vary from person to person or culture to culture, the outcomes of their perceptions can cause them to make different value systems for perceiving the realities of those phenomena. In other words, the difference in perceiving the actual value system depends on cultural value orientations. In fact, there are two systems of cultural perceptions: actualism and possibilitism. Cultural actualism perceives the existence of phenomena as they exist. Cultural possibilitism perceives that the existence of phenomena is based on how they can possibly be perceived. Therefore, we should note that multiculturalization should not be focused on demographic numbering of the majority of people’s beliefs. It should be denoted to the international values of all cultures for maximization of consequential positions—because the international value objectives are maximization in the path reaching to the ultimate intellectuality. Also, it should not be restricted by political or racial cultural boundaries. However, multiculturalization in terms of virtual intellectuality should be a nonconsequentialistic framework for valuing the universal moral and ethical doctrine.

Cross-Culturalization

Cross-culturalization is the task of optimization of diversified cultures. One of the major tasks of international managers is to identify similar cultural values and beliefs among home and host countries. These similarities have been observed from the common characteristics of all people around the world. There are several motivational theories which indicate that human needs are similar and universal. Similarity and universality of human basic needs indicate that people are responding to these needs according to their cultural orientation. It should be noted that this assumption that “one size fits all” is misleading, because people are different and consequently their levels of need-satisfaction are different too.

Traditionally, all cultures have four main functions or, more accurately, four levels of social functioning. These are: (1) mass-cultures and subcultures, (2) enhanced cultures and enriched cultures, (3) utilized cultures and facilitative cultures, and (4) refined cultures and crystallized cultures.

Mass cultures and subcultures. Mass cultures refer to information we receive through written documents. While mass culture is often denoted as the common culture, it also has to be treated as an important component of a national culture, as it is referred to, the commonality of value systems and beliefs of a nation. The term subcultures, on the other hand, denotes implicit or explicit special group cultures to conform to a common culture. Subcultures are specific segments of class-cultural and/or group-cultural value systems which exist outside the core of a mass culture. Subcultures occupy the most important portions of a culture—such as political, professional, occupational, and so forth. For example, American common cultural value systems resemble those of the Europeans. However, the judiciary and educational subcultures of these two continental cultures are different. Americans place a particular importance on individualism, while Europeans emphasize socialization of the basic needs (e.g., social medicine and free education). However, the Middle and Near Eastern cultures often sacrifice personal comfort and endure financial hardship for the sake of maintaining their familial brotherhood ties.

Enhanced cultures and enriched cultures. Enhanced cultures emphasize spirituality of faith and belief in daily expected behavior. These spiritual cultural values are the foundation of socially acquired needs in a rich culture. These spiritual needs have come from religious and humanitarian values, processing cultural thoughts and behaviors—such as educational, religious, ethical, moral, and so forth.

Cultural utilizers or facilitators. Cultural utilizers or facilitators utilize certain cultural traits and patterns for harmonizing thoughts and behaviors; such as liberty, freedom, democracy, and so forth.

Cultural refrainers and crystallizers. Cultural refrainers develop certain working skills for cultural reproduction—specialization in research and development in alliances through basic research, applied research, development research, accelerated research, and cross-matching research.

Utilized cultures and facilitative cultures. Utilized cultures provide certain cultural traits and patterns of values for harmonizing thoughts and behaviors. These trends and patterned value systems have come from political ideologies such as liberty, freedom, democracy, and so forth. Facilitative cultures stem from educational and technological capabilities such as research and development (R&D), the mainframe of computer systems, computer-controlled numerical systems, computer-controlled robotics systems, computer flexible manufacturing systems, computer-aided design systems, and computer-integrated manufacturing systems.

Refined cultures and crystallized cultures. Refined cultures develop certain working skills for cultural reproduction such as specialization and development in alliances through basic research, applied research, development research, accelerated research, and cross-matching research. Crystallized cultures develop highly codified sophisticated value systems for creating and maintaining a very capable and in tune know-how and technology in order to maintain cultural supremacy.

All of these functioning cultures integratively move a culture toward the future. In cross-culturalization, there are two dimensions which should be recognized:

Internal-dominated dimensions of a culture.

External acculturalization dimensions.

On one side, all native cultures utilize techniques and methods for developing a more or less culturally differentiated type of outcome. On the other hand, people cross their native cultural boundaries toward integration heterogeneously or unificationally in a homogeneously oriented environment—toward a new system of class domination or denomination.

For understanding the real means and ends of cross-culturalizational effectiveness, we must start with analysis of the following causes and effects:

Comparative analysis of cultural functionalization in terms of political interests, scientific acquisition, economic development, and technological innovation

Comparative analysis of social orientation and class-relations in terms of consequences of their behavior

Comparative examination of new perceptions and class-relations influence the courses of action and directions of societal changes

Comparative analysis to reaching down to the depth of the levels of both national and international crises and solutions

With application of these scientific tools in cross-culturalization, we may be able to realize the common elements and grounds which can be effective in cross-cultural relations. Through cross-culturalization we are able to communicate with and relate ourselves beyond the native boundaries of our mind and visualize the world in which we live. The scientific, vocational, educational, and cross-national acculturalization offers so many inter-cultural challenges for increasing more cultural effectiveness.

In cross-culturalization, differences do not necessarily mean barriers. They can become bridges to understanding and enriching our relations with the world of outsiders. In a cross-culturalization process, we are selecting, learning, conceptualizing, and interpreting new values and will try to adopt them in our culture or try to adapt other culture to our culture.

Parochialization

Through the history of humankind, the relationship between geographical locations and demographic movements, as well as the adaptation of people from one area to another, exist for a wide number of reasons. As a consequence of people movements, both host and home populations benefit and suffer from the strengths and weaknesses of one another. From one dimension, the cultural assimilative theory of parochialism exposes host people to culture shock, because they are not able to express and exercise their own cultural patterns and expectations.

Parochial culture means viewing the world solely through one’s own eyes and mind’s perception (Adler, 1986). A culture with parochial perception does not recognize another culture’s different ways of thinking, perceiving, and proceeding, nor that such differences have serious consequences. A parochial culture is attached to the idea of being part of its own culture. Although all cultures to a certain extent are parochial by this definition, some cultures are more so than others. Moreover, a parochial culture is inordinately proud of its cultural ideology, myths, and utopian visions and seeks to have other countries adopt them. This egocentrism seems to convince the members that they have a unique mission in the world and that they are superior to other cultures.

Parochial cultures have problems, such as racism, group superiority, ethnocentrism, discriminating perceptions, bias, stereotyping, ambition, expansionism, and externalism. A parochial culture does not recognize cultural diversity or its impact on their population’s lives. In a parochial culture, members universally believe that “their way is the only way,” and “their way is the best way,” to conceive, perceive, and proceed. No nation can afford to act as if it is alone in the world (parochialism) or better than other nations (ethnocentrism).

Enculturalization

Perhaps the biggest difference between past and present cultural contacts is the trend of cultural assimilation and integration. Cultural assimilation is related to enculturalization; cultural integration is related to acculturalization.

Assimilation is the term used to describe the swallowing up and digesting of one culture by another. This occurs when an enhanced cultural group and/or a capable technopolitical group gradually and/or suddenly forces the dominated groups to adopt the lifestyles and often the languages of the dominant cultural power group. Interculturally, after a few generations of assimilation, minority groups tend to lose their original cultural identity and heritage and become members of the mainstream of the dominant culture (Furnham and Bochner, 1986: 26). The best example of assimilation is the “melting pot culture.”

Therstrom (1982: 12) indicates that the title of a 1909 Israel Zangwill play, The Melting Pot, has often been used as a metaphor to describe the phenomenon of people changing their names, learning a new language, and adapting their culture to better blend into a new cultural lifestyle.

The melting pot culture indicates that the ideal objective of a nation is to assimilate people into a unified system through public cultural trends in order to reduce the cultural and structural divisions between minority and majority groups (Zangwill, 1909: 193).

Under the melting pot model according to Abramson’s (1980: 150–60) views, there are three possible forms of complete assimilation. Each involves a different path and a somewhat different objective. First, a racial or ethnic minority group is assimilated or absorbed into the wider society. For example, many Asian and Pacific ethnic groups have assimilated themselves into the Hawaiian culture over the past several centuries. Second, minority racial or ethnic groups may assimilate into the majority culture through their religious faiths. The Ethiopian Jews that immigrated to Israel are an example of this type of assimilation.

In today’s international business transactions, multinational corporations cannot implement the melting pot culture because the trends of conducting businesses changed dramatically in the 1990s. Multinational businesses are moving to global multiculturalism, because managers perceive that their success is bound to globalization rather than denomination of their businesses. In addition, global corporations are learners and collaborators with host nations rather than hierarchical and controlling.

In modern societies such as the United States of America, corporations do not perceive enculturalization anymore. They are thinking and practicing accommodation and even appreciation of diversity. No longer are American corporations thinking in terms of assimilation; instead, they think and perceive of “managing” diversity.

Acculturalization

When two or more culturally disparate groups of people come into contact with one another, they will have enormous impacts on one another’s social structures, institutional arrangements, socioeconomic and political processes, and value systems. The nature and the extent of these effects depend upon the conditions under which the contact occurs. Usually, cultural contact groups are emerging from travelers (e. g., tourists, students, scholars, traders, immigrants, missionaries, and, in a general term, integrators).

The term integration is used interchangeably with assimilation. However, these terms have quite different meanings and outcomes in the process of intraculturalization. Integration refers to the accommodation that comes about when different cultures maintain their respective core cultural identities, while at the same time merging into a superordinate group in other, equally important respects (Furnham and Bochner, 1986: 28). For instance, historically Iranian culture is an example of a successfully integrated multiracial and multireligious society which shares a common culture, while on the one hand, it is composed of Persians, Turks, Turkmen, Kurds, Luris, Baluchis, Afghanis, Azaris, Gilakis, and Arabs, and on the other hand religiously it is composed of Shiite and Sunni Moslems, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, Baha’is, Armenians, and Assyrians. Although the official language of Iran is Farsi and all these enthnicities speak Farsi for their formal communication, at the same time, all ethnicity and/or religious groups communicate with one another with their own dialogues and practice their own cultural traditions. It is surprising that even after the Iranian Islamic Revolution, which took place in 1979, that Iranian culture still is highly integrated and acculturalized.

Biculturalization

The most fundamental concepts of biculturalization with which I will deal are ethnicity and race. I will have two views concerning biculturalization. First, biculturalization is viewed as an objective unit that can be identified by distinct ethnic traits of a group of people. These people remain loyal to their original ethnic group while imitating and practicing the new culture (e.g., Anglo-Franco: Canada; Germano-Franco: Switzerland; Hispanic American and African American: United States). Second, biculturalization is viewed merely as the product of people’s thinking of and proclaiming dual cultural value systems among both home and host countries (e.g., Mexican American, Texmex, Arab Ajam). To avoid the extreme of these views, biculturalization can be defined as both an objective and a subjective phenomenon. However, we need to identify two versions of biculturalization: in-culture and out-culture.

In-culture refers to the way of perceiving biculturalization within the “natural” boundaries of the geographical proximity of two cultures to each other (e.g., Texmex, which identifies Mexicans and Texans on the border area, such as Laredo, or Calexico on the border area of California and Mexico).

Out-culture refers to the way of perceiving biculturalization beyond the proximity of the geographical boundary of two cultures (e.g., French Canadian, English Canadian). However, it should be noted that biculturalization is a form of reciprocal social affiliation, dependency, and binding between two different cultures.

An overview on the common body of knowledge concerning multiculturalism can provide a necessary foundation for the study of human behavior within multicultural organizations. Defined as a common body of knowledge, multicultural behavior is the essence of philosophical, natural, social, and behavioral sciences, and technology. Multicultural synergy can be defined as the mathematical analogy that 2 + 2 = 5 instead 4. If multicultural synergy is beyond of the sum of the total parts of a culture, then positive synergy has occurred.

Multicultural synergy relies on synergistic knowledge-based integration of philosophy, technology, and sciences. Philosophy is the basic intellectual foundation of the human mind concerning the examination of one’s own judgment. Philosophy is the integration of all knowledge to understand the cause and effect of existence. Cosmology is concerned with realizing the nature of reality and the place of human beings in the universe. Theology is essential to understanding the human mind and its relation to the nature of the superpower—God. Ontology is the idea of existence due to the relationship with nature. Causality is concerned with the ultimate causes of things being what they are in reality. Causalogy is a method of searching through pragmatic applications of scientific reasoning to identify the major elements or processes of effective forces which can manifest the original factors of a process or an accident. Epistemology has to do with the problem of knowledge. Axiology is concerned with the problems of values. Morality means the habits of right and wrong conduct, or good and bad, virtuous or vicious, and to right and wrong in relation to actions and conducts. Ethics is concerned with the human social conduct, activity, and behavior of the societal conscious awareness of a group of human beings. Aesthetics pertain to cultural senses of beauty, excellent thought, and illustrative elegant visual tastes.

Science deals with humankind’s understanding concerning the detection and formulation of the real world experiences inherent to properties of space, matter, energy, and their interactions. Science is a rational convention related to the generalization of the environmental norms, expectations, and values. Observational sciences include astronomy, geology, physics, and chemistry. The primary aim of these sciences is to deliver cause and effect relationships between material things. Natural sciences identify the real characteristics of the causes, functions, and structures of all material things. All material things can be explained in terms of their natural causes and laws, without attributing moral, ethical, spiritual, or supernatural significance to them. The foundation of all natural sciences is based upon phenomenalogy of mathematics, quantitative methods, and logic. Social sciences include economics, political sciences, demography, history, and geography. Economics is the study of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Politics is one of the behaviors aimed at exercising influence through exertion of power. Demography is the science of biostatistics and quantitative statistics of populations including births, deaths, diseases, marriages, numbers, means, percentages—all both material and nonmaterial value systems, etc. History is the branch of scientific analytic knowledge dealing with past events. Geography is the science dealing with the areal differentiation of the earth’s surface, as shown in the character, arrangement, and interrelations over the world of such elements as climate, elevation, soil, vegetation, population density, land use, industries, or states.

Behavioral sciences include anthropology (physical anthropology, cultural anthropology, archaeology, anthropological linguistics, and ethnology/ethnography), sociology, and psychology.

Anthropology is literally defined as the science of human generations with interactions between generations and environments, particularly cultural environments. Sociology is traditionally defined as the science of society, for searching and solving social problems within the context of its dynamic processes, purposes, and goals. Psychology has been defined as the science of behavior.

Chapter Questions for Discussion

How can the common body of knowledge facilitate better understanding of human culture?

How does philosophy differ from sciences?

How do natural sciences differ from social and behavioral sciences?

Why is scientific study of multicultural behavior important to multinational organizations?

Briefly summarize the various schools of thought in psychology.

Briefly summarize the various branches of anthropology.

Learning About Yourself Exercise #4

What Do You Need?

Following are fifteen items for rating how important each one is to you on a scale of 0 (not important) to 100 (very important). Write the number 0–100 on the line to the left of each item.

_______ |

1. |

The need for sex |

_______ |

2. |

The need for affiliation |

_______ |

3. |

The need to nurture |

_______ |

4. |

The need for guidance |

_______ |

5. |

The need to egress |

_______ |

6. |

The need to achieve |

_______ |

7. |

The need to dominate |

_______ |

8. |

The need for prominence |

_______ |

9. |

The need for attention |

_______ |

10. |

The need for autonomy |

_______ |

11. |

The need to escape |

_______ |

12. |

The need to feel safe |

_______ |

13. |

The need for aesthetic sensations |

_______ |

14. |

The need to satisfy curiosity |

_______ |

15. |

Physiological needs: food, drink, sleep, etc. |

Turn to the next page for scoring directions and key.

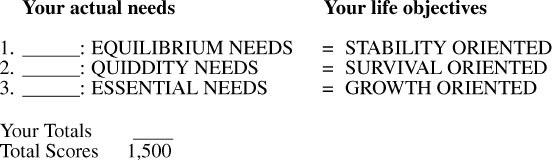

Scoring Directions and Key for Exercise #4

Transfer the numbers for each of the fifteen items to the appropriate column, then add up the five numbers in each column.

The higher the total in any dimension, the higher the importance you place on that set of needs. The closer the numbers are in the three dimensions, the more multidimensionally balanced you are.

Make up a categorical scale of your findings on the basis of more weight for the values of each category.

For Example:

After you have tabulated your scores, compare them with others. You will find different value systems of needs among people with diverse scores and cultural need orientations.

Case Study: Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment: Doing Good in the Nature of Bad? Or Doing Bad in the Nature of good?

Prior to the twentieth century, diagnostic, treatment, and prognostic procedures for the medical profession were thought to be effective on the basis of experiments. Physicians were very careful to not violate medical ethics. Nevertheless, most experimental clinical research studies were harmless, but ineffective. In the twentieth century, medical practices began to apply the scientific results of the structured random clinical trials (SRCT). The purpose of the SRCT was to validate application of research-oriented treatments by physicians. The human subjects were selected for admission to a SRCT project on the basis of diagnostic criteria formulated by prescribing as precisely as possible in order to ensure that patients all have the same illness. Implementation of the SRCT projects were based on procedural screening systems:

To find a group of patients who have similar diseases.

To divide patients into two major groups: (a) control group, (b) experimental group.

To identify the placebo control group from a regular control group. A placebo group is referred to as a group of patients who believe that the placebo effect can be helpful for their medical treatments. Placebo patients believe that a physician can do something that will relieve the illness and typically they have some improvement from the psychological beliefs and/or religious faith for healing their illnesses.

To categorize a control group into two identical groups for the purpose of eliminating doubt from the experience. This type of control group is called double-blinding.

Random assignment refers to alternative treatments randomly for the purpose of identification of differences attributed to the treatments.

Statistical significance refers to the importance in discussions of the ethical issues related to SRCTs.

Among numerous bioethical research projects is the famous Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Tuskegee was conducted in a covert project by the government of the United States from 1932 until 1972. The details of the Tuskegee research project were revealed to Peter Buxtun by a U.S. Public Health Service whistle-blower, Jean Heller, in 1972. Buxtun revealed the testing procedures to the national press in full detail. What has become clear through Jean Heller was that the Public Health Service (PHS) was interested in using Macon County, Alabama, and its inhabitants as a laboratory for studying the long-term effects of untreated syphilis; instead of in treating this deadly disease. At that time, the Tuskegee area had the highest incidence of syphilis in the nation, and more than 400 of these men had sexually transmitted diseases, for which limited treatment was then available (U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, 1993: 3).

The study has become a powerful symbol of ethical misconduct in human research. In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service and several foundations began a study on approximately 600 male black American citizens in Tuskegee, Macon County, Alabama. All 600 subjects (399 experimentals and 201 controls) were desperate poor people. They were promised free medical treatment, food, and burials. Initially, they were given mercury and arsenic compounds—then standard therapy—when the drugs were available. Also, they endured spinal taps without anesthesia and were denied penicillin long after it became available in 1945.