WHAT IS EDITORIAL PRODUCTION

WHAT IS EDITORIAL PRODUCTION

Editorial production on a daily paper, morning or evening, begins with the selection of the contents for the day’s issue. This does not mean that the writing part has finished. News will continue to be gathered and written up to the last deadline of the last edition, background features will be prepared and photographs shot, but once decisions begin to be taken about the placing of stories in the pages, that is editorial production.

Central to this process is the paper’s team of subeditors, by whom the various tasks of editing are carried out. A prime mover in this early stage of producing the paper is the senior subeditor who selects and shortlists from the mass of incoming material the stories most likely to be used. Since copy is the name for all the material keyboarded in by the writers, copytasting is the word used for the selecting of this material, and the person who initiates the process is the copytaster.

News creation is a round-the-clock operation into which a newspaper tunes during its hours of production. On an evening paper, where work begins about 8 a.m., the newsroom deals first with overnight stories and follow-ups from the previous day’s news. Because of the time difference, foreign copy will be at first predominantly from America. This is why the early editions of evening papers often carry American-originated material which is later thrown out as the flow of home and European stories picks up with the start of the day’s activity cycle.

As edition succeeds edition, from about midday there is a strengthening of the home news-of-the-day content with running stories being updated between editions into the late afternoon, peak time for the inflow of stories being around 2 to 3 p.m. Afternoon cricket scores replace morning and overnight ones; the lateness of racing results is a guide to the press time of the edition you have bought.

The morning paper cycle begins at about 11 a.m. or midday, with edition press times from about 7 p.m. depending on the distribution areas and where the printing presses are that serve them. National papers, printing in a variety of centres these days, publish earlier for more distant areas. Provincial morning papers with their closer distribution can afford to work until well into the evening before getting their first edition away.

Morning paper newsrooms first of all mop up the news of the day, looking for follow-ups where stories have had a good run in the evenings and on television, and giving more detailed versions of stories the evenings have only nibbled at. They have the benefit of evening events, speeches, meetings, functions and theatres and have more time for set-piece interviewing. Because of the time difference, morning papers are stronger on European news and are first with the day’s events from Australia and the Far East. They also have time for polished detailed background features and situationers which give depth and perspective to their coverage.

By the time the last bit of updating has been done and the last edition (not normally later than 2 a.m.) has gone to press, the flow of home and European stories has subsided and the first stories are coming in from America. The news cycle is ready once more for an 8 a.m. start-up by the evenings.

Creating the news

News – features are dealt with later in this book – arrives in a newspaper office from a variety of sources. Common now to all reporters, feature writers and agencies is the practice of keyboarding copy straight into the office computer, from which stories are recalled on to screens for editing into their page slots.

Agency copy is entered likewise and is automatically routed to the desk whose job it is to read and deal with it. Local references are typecoded to help local paper subscribers and draw the news editor’s attention. There are not many jobs these days being carried out by village correspondents where ballpen, typewriter and telephone are the means of origination.

Staff reporters

Staff reporters are the most useful and controllable source of news and the likeliest source of exclusives; all papers like to have something their rivals haven’t got. Numbers vary from about ten to twenty on a small evening paper to forty or more on a national daily. They work from the newsroom or from branch offices and sometimes independently in districts, and they are controlled and briefed by the news editor (or the chief reporter on smaller papers).

Jobs can vary from a simple telephone inquiry, or personal call resulting from a letter or information received, to complicated jobs involving a team of reporters and sometimes several locations. Some stories might have both local and national, or even foreign ‘ends’ and last all day or several days.

If there is no time to get to the office to keyboard copy into the computer, reporters, using portable workstations, file direct into the system by telephone modems; otherwise their copy is taken over the telephone by copytakers, who keyboard it in for them. Where there are bigger staffs a newspaper might use a number of reporters as an investigative team on long-term news projects under a leader or project editor. This is usually planned into the paper in advance as a special news feature.

Freelances

Freelance reporters are used mainly on specialist assignments or for holiday relief work and are paid for the job or days or weeks worked. They are not tied to a paper except where they have a specific contract covering a job or sequence of shifts. Some specialize in investigative writing which they sell to the highest bidder.

Local correspondents

These are journalists working for a local paper, or as local freelances, who are accredited by retainer fee or some special arrangement to a bigger paper to cover stories in the area. They get lineage (a fee per line) for stories used or ordered. The arrangement usually precludes them working for a rival paper. They cover wanted stories where a staff reporter is not available.

News agencies

National and international news agencies work round the clock to provide a variety of services for newspapers all over the world, collecting material from bureaux and correspondents in cities and countries, checking and editing it and distributing it to subscribers.

Most countries have their own national agencies whose services are used by small and medium-sized papers to fill gaps in coverage, or even provide all but local coverage. Agency stories can be used as check sources and many agencies provide news pictures. The international ones such as Reuters, Associated Press, United Press International and Agence France Press are the prime sources of foreign news for papers who have few, or no, foreign corespondents, and also of newsfilm and sound reporting for television and radio. They feed into national news networks stories affecting a country’s own interests and their nationals abroad. News agency correspondents are often the first to break important foreign stories.

Agencies operate in a similar way to newspapers through staff reporters in main centres with local correspondents, or stringers, filing in from the districts. The subediting, which includes headlining, checking and editionizing for the various services, is carried out at the main offices and serves morning, evening and Sunday papers. Most papers in Britain take the Press Association (national) and Reuters general services and some sport, financial, situationer and other services, depending on their contracts. A rent is paid for each.

Handouts

Handouts arrive in newspaper offices in great numbers from all sorts of organizations, including the Government, and sometimes from celebrities, via press officers, whose aim is to reach the public through the newspaper. They are usually given to reporters to read or to specialists whose field they cover in case they contain something of interest to the readers. Reading them can be a tedious and even boring job, but it can yield important stories over a wide field including, for example, housing statistics, immigration, race problems, technology breakthroughs, new cars and copy for consumer columns.

The newsroom

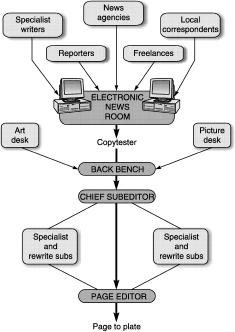

Though the newsroom is the heart of the gathering side of the business (see Figure 8) it is concerned with production, too, for it is here that decisions are taken that will shape the news content of the paper. And, of course, the keystrokes made by the writers are the keystrokes, subject to editing, that set the paper in type.

The news editor, who runs the newsroom, is one of the busiest executives on the paper. The assessment of a news situation depends at the outset on the news editor’s judgement: what news is to be covered, in what depth, and who is to do the work. Reporters and correspondents are briefed so that copy is filed on time and important aspects of stories not missed. Stories are commissioned from freelances and outside specialists, agency input monitored, work checked to see it is done properly, handouts, correspondence, expenses, travel arrangements, interviewing for jobs and a hundred and one other things dealt with. In this work the news editor is helped by a deputy, usually a couple of assistants and a secretary.

The news editor keeps a check on where the staff are, listens to their calls in, decides when to extend coverage of a story, when to ask for more copy and when to call it a day where a story has ‘fallen down’. The advent of the electronic newsroom helps. News editors now check reporters’ files on screen, send back stories where coverage is not enough or has failed in some way, and route stories to the copy taster and chief sub as they become ready for the pages. There is sometimes a reverse traffic on screen of stories sent back by the chief sub who is not happy with them.

The use of portable workstations by reporters has improved newsroom organization. District offices can be controlled electronically through the newsroom’s keyboards, with stories and messages being routed to and fro.

Village and country correspondents of provincial papers now often have their own portable terminals: Women’s Institutes and flower show results have entered the computer age. Most offices have a number of such terminals in use among part-time contributors, while many with their own PCs link up to the office computer by telephone modem to file copy. It all makes for more effective control of coverage,

By the time the editing and making up of the pages begins, a good deal of the decision-making has already taken place. The material has passed through the newsroom system. Stories have been checked by the news editor and sent to the chief sub. Among them, depending on the facts of a story, the amount of space available and the volume of news about, are the candidates for the day’s pages.

Figure 8 The electronic newsroom shown as the fulcrum of copy flow on a typical national daily. Stories are keyed into the system by the writers, checked by the news editor, sorted by the copytaster, planned and placed by the back bench or chief sub, and called up on screen for subbing and building into the page.

The copytaster

In theory, the editor reads everything that is likely to get into the paper. In practice this is seldom possible, although editors are usually given a copy of all reporters’ stories, or can call them up on their personal screens.

The editor, through informal discussions with executives during the day and through the briefings and debate of the daily planning conference, is familiar with the more important stories that are being covered, and at an early stage has ideas about the thrust and balance of the paper. The likelihood of some big stories is known in advance and their place in the paper can be prepared. There are days, however, when because of other concerns, the editor has little time to focus on the whole news input and has to leave some decisions to his executives. The role of the copytaster who, come what may, reads everything that is written and submitted, is thus an important safeguard.

The copytaster is usually the first production journalist to arrive for duty in the editorial room. Here, at a desk close to the chief sub (Figure 8) and usually just in front of the back bench, the process of ‘tasting’ goes on until the last edition of the day has gone to press. The work is generally split into two shifts with a deputy taking over later in the day.

This is the journalist figure most maligned by the media sociologists. The copy taster is the ‘gate-keeper’, the one who lets in or shuts out stories according to the indoctrination practised by the proprietor/organization; who assesses news to a set of stereotypes deeply embedded in his professional soul; who bends circumstances to fit preconceived stereotypes and pigeon holes; the stopper when anything original or damning appears at the gate; the one who protects the readers, the people, the organization from truths that jar…and so on.

The job, in reality, is nowhere near as influential or as sinister. The copytaster is unfailingly a senior subeditor who understands the paper’s market and readership, and his (or her) function is to sift through and sort all incoming stories and reject those that are unsuitable or unusable. The aim is to shortlist and reduce to manageable proportions what is sometimes a mountain of material so that the night editor, chief subeditor, or whoever is in charge of page planning, can set to work on the edition without their time being wasted.

The job is a ‘hot seat’. The danger facing all copytasters is of ‘spiking’ a story that turns out be one the editor decides should have been carried. This is a special hazard on national papers when the rejected story can turn up in a rival paper. The safeguard against this happening is the copytaster’s own finely tuned news sense and familiarity with the paper’s style and content.

Measuring the news

A quick examination of newspapers on the same day will reveal that while some stories are common to many, there is a variety of opinion among them as to what news to carry. There is a difference in coverage in the daily press between newspapers that circulate nationally and regional and local ones. Within these bands are further differences in market and content.

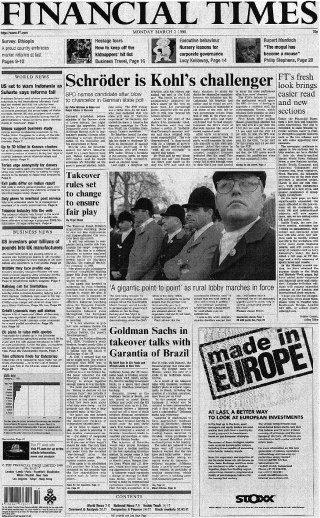

Some papers exist to propagate the views of political parties or churches or minority groups or interests. Some national papers – in Britain, for instance, The Times, The Guardian and the Daily Telegraph – have an up-market readership interested in cultural things and world news, and in technology and education. Some are highly specialized, such as the Financial Times with its business news (and absence of sport). At the same time, many tabloid, or half-size, papers – which have a bolder display – such as The Sun and The Mirror, sell to a popular readership and are strong on pictures, human interest news and stories about TV personalities, showbusiness, sport and the Royal family.

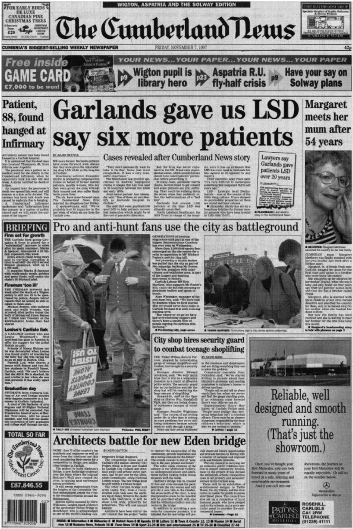

Town evening papers reflect the life and activity in the circulation area and carry only the more important national stories and very little foreign news. Some county papers are full of news about the farming community, village activities, local wedding and social gossip of the area. News about dominant industries such as steel or textiles, in which many readers work, can feature strongly in regional papers. This is all quite natural. They are performing a service for their readers (see Figure 9).

There is also a difference in weight of coverage between daily and Sunday papers, and between provincial evening and weekly papers. The once-a-week publications devote more space to features giving depth and background to the news of the week, and to comment and opinion.

It will be seen from this brief survey that there can be no universals in news assessment. While a copytaster on a national ‘serious’ daily and one on a provincial evening follow the same routine, the yardstick by which they measure the copy input is not the same.

This does not mean there can be no definition of news. News remains, in any circumstances, the first tidings, or knowledge or disclosure of an event. By the same token, a secret or unknown event remains secret and unknown until, upon its disclosure, it becomes news. For example, the marriage in secret of a celebrity might take ten years to be revealed to the public. Then it becomes news. Thus we can say that, in terms of a newspaper’s content, it is not the event itself that is news but its disclosure.

Figure 9 Serving the community – this well filled broadsheet front page from the weekly Cumberland News uses a stylish lower case type dress and well-planned highlights to present ten newsy stories, all from the circulation area. For good measure it runs an edition blurb with page cross-references

Once a news situation has been disclosed and made public it ceases to be news. A notable news story that appears in a paper one day will be referred to the following day only in the light of some new aspect that has cropped up. This is called a follow-up.

Yet it is not sufficient for an event to be news within this narrow definition for it to be worth printing. It must also be of likely interest to the readership which, as we have seen, varies from paper to paper. There is little point, for instance, in a country weekly on the Welsh border, filling its pages with news about Brazil or China, or the Financial Times concerning itself with the result of the three-legged race in a school sports in Cumbria. The journalists know their paper’s market – they have to know it to do their job properly – and they select the sort of news that is right for it. Even so, copytasters will find that among the copy that flows into their electronic baskets each day is a percentage that does not fit the pattern. The first job is to weed this out.

Another consideration in news assessment is the sheer volume of the commodity available on the day. A newsroom or agency does not stop filing when it has reached a given number of stories; it goes on covering the news wherever it breaks. The gatherers accept that it is the job of the editor and the editorial staff to decide how much of it will be used and at what length. While the factors governing this measuring of news become instinctive in an experienced copy taster, it is worth noting down what they are. Also, it should be repeated that it is not the copytaster’s job to select what goes into the paper but rather to exclude what, for various reasons, is unsuitable, shortlisting the remainder into a manageable amount.

A story is rejected if:

1 It is geographically outside the paper’s market, unless it is of special importance (depending on whether it is a national, regional or local paper).

2 It is outside the readers’ range of interests (whether quality, upmarket, popular or specialist).

3 It does not extend any further material that already appeared in the papers.

4 It appears to be merely seeking publicity for someone and has otherwise little reader interest.

5 It is legally unsafe (unless it is worth making safe), in bad taste, racist, clearly inaccurate, silly, or based on rumour.

6 It is simply not good enough, or interesting enough, on a day when there is a great deal of news about.

The last point demonstrates why absolutes are not possible in measuring news value. Even if a story fulfils most of the normal criteria, the decision on whether it is used and, if used, how much space it will get, can depend on the number of good stories demanding to be used, the existence of other similar stories, and the space available on the day. It is not generally realized that the amount of space for editorial use in a newspaper rises and falls in response to the percentage flow of advertising and not to the volume of news available.

The consequence of this that a story that might justify being given a good space one day might warrant less on another. The best day for a good show to a story is when the copy flow is known to be slack – on the Sunday shift working for a Monday morning paper, for example.

The alternative on such days might seem to be to leave blank spaces in the pages, but this would look silly and also would not be liked by the reader. What happens is that certain exclusive stories are held back (or planned forward) for publication on slack days, a greater number of foreign stories used and more space given to features, or picture display. It has to be said that however uneven the flow of news, there are very few days in the year when the editor is at his (or her) wit’s end what to put into the paper, but the phenomenon just described does account for the good and bad days that newspapers have, which are sometimes noticed by readers.

News patterns

The four pages reproduced in this chapter, three provincial and one national, demonstrate the working of the news selection patterns we have just described.

The Cumberland News page one (Figure 9) provides model coverage for a weekly serving communities in a far-flung area. The ten stories range from drug abuse in a hospital and a woman meeting her mother for the first time in 54 years, to a hunt supporters’ demonstration, a competition for a new Millennium bridge at Carlisle, and a man of 88 found hanged. Even the fillers tell about a local lad who was the boyfriend of Louise Woodward, the au pair accused of killing a baby in the US, and about more local jobs expected following a Marks & Spencer’s expansion. Inside there is hardly an area of activity from market and stock prices to Women’s Institutes that does not get its space.

The two evenings from Birmingham and Bristol (Figure 10) cannot compete with this on scale but, in tabloid fashion, they provide a powerful display for stories of strong local interest in eye-catching layouts. Both are good-looking easy-to-read papers for busy city dwellers looking for a quick round-up of the day’s news as it affects them.

The Financial Times (Figure 11) shows how a specialist broadsheet can pack in the news while still achieving quiet, readable elegance. The four main stories are given a good space. The air crash picture, by the standards of any daily, is an eye-catcher, and there are still to come a column of 17 briefs on companies and economies around the world, a currency chart, a contents list, and three colour blurbs about items in the inside pages.

Figure 10 How the tabloid evenings do it – an inside news page from the Birmingham Evening Mail and a smart front page from Bristol’s Evening Post. Effective placing of pictures and polished use of the tabloid style characterize these sans type layouts

Figure 11 With its full-width masthead, use of blurbs and front page colour (though sometimes oddly printing on pink), the Financial Times has come a long way in the last few years. This page one, with its Times Roman lower case format and studied elegance of design, shows that a paper with a mostly business readership does not have to look dull

Production start-up

In today’s computerized environment it is the tools rather than the principles that have changed but, if you can imagine an electronic pile of text, pictures and advertisements on the one hand and the printed paper coming off the press on the other, then editorial production is what happens in between. We will now look at how this process begins.

We will take, as our example, a small tabloid evening paper running a new page-to-plate make-up system based on Apple-Mac PCs and the latest version of QuarkXpress. It is operated by a small team of subs who, if you like, are page editors, each of whom sub the items for their page and make up the pages on screen, complete with pictures and advertisements, to plate-ready state. It is a system that suits a paper with modest staffing, few executives and no art desk.

The back bench, or control desk (in Figure 8), consists of the deputy editor (who would be the night editor on a national morning paper), and the chief subeditor and his deputy, who doubles as copytaster. The editor occasionally drops by and sits in when not tied to his (or her) office on other duties; it is a paper where the deputy editor has the role of production supremo.

Suppose you are the copytaster. Your ‘in’ queue of stories from the newsroom has already begun to mount by the time you report for duty and your first task is to check your directories or folders and ‘read in’. You make a few notes on a pad (no office is entirely paperless!). The deputy editor and chief sub, who have called up particular stories on their screens, are roughing out early pages on half-size layout sheets which they will hand to the page subs who are beginning to arrive.

While you are reading in, the deputy editor and the chief sub confer with the editor about the general balance and expected main contents of the day’s paper in the light of what is known. They tell you what important items are expected and any particular things to look out for.

Your job is now to read and draw the important stories – especially any unexpected ones – to the attention of the night editor or chief sub and put them into their queues; to put the clearly ‘dead’ ones into an electronic ‘spike’, and to put doubtful or possible stories into pending queues to be called up as needed. You look out for stories with edition area interest and bring them forward at the right time, and route to the picture desk any stories needing pictures in case this has not already been done.

You might feed a flow of useful shorter material into a special queue to the chief sub to be used as fillers at the bottoms of pages. The number of ‘out’ queues you operate depends on the amount of copy and the degree of pre-sorting needed to suit the number of pages.

Reading all copy before it is subbed is useful. It enables you to spot any errors or failings in stories and to send them back in good time to the newsroom for more work or inquiries. If you have a separate agency input it enables you to suggest to the newsroom ideas for local ‘ends’ to agency stories where these have not already been put in hand.

Copytasting on screen makes life easier. You can call up the complete directory of stories held in a given queue (i.e. newsroom, agency, sport, etc.) and get the source, name, catchline and first few lines of any story, and also its length. Stories can be sorted into subject and priority queues within the computer so that the right material is drawn to the chief sub’s attention at the right time. You can queue related stories together, including edition area copy.

Some national dailies refine the tasting process by filtering copy through a rough and fine taster, or through separate home and foreign tasters, where there is a heavy copy input and a lot of pages to fill. The aim is not only a fail-safe reading operation but also a continuously creative assessment of the copy flow throughout the editions.