INTRODUCTION: THE QUARK REVOLUTION

A sociologist writing about the press divided newspaper staffs into gatherers and processors. The gatherers: reporters of all types, photographers, feature writers and, of course, news and picture agencies. The processors: editors of all types including departmental heads, layout artists, subeditors and not forgetting the office lawyer by whatever title.

The writer in question noted that the processors marginally exceeded the gatherers in numbers. This was to be expected since, unlike books, newspapers are complicated things requiring a good deal of planning, decision taking, sorting and choosing of material and targeting on particular readerships, whence stem techniques in text editing, headline writing, illustrating and typographical display. These, of course, can vary considerably from paper to paper. Newspapers require editing at its most varied and complex.

At the heart of the process are the subeditors. The editor of a newspaper – that is the editor – cannot carry out, and never has carried out, all the editing functions, although he (or she) remains responsible, legally and practically, for what appears when the paper is printed. It is the subeditors, varying in numbers depending on the size of the paper, and multi-skilled to a greater degree since the demise of old printing, who produce the paper to the editor’s broad policy and plan.

Editorial production, for that is what this complicated process is called, calls for a great variety of skills from subeditors. Knowledge of type and page design and the use of pictures are needed to produce balanced and eye-catching layouts in the style of the paper. Knowledge of page make-up is needed to see that everything fits correctly without clash and problems and that the finished page is finely honed – these days on screen – ready for the plate-maker. There is no old-fashioned print overseer to see to this aspect.

Editing the text is a fundamental skill in all newspapers, and in all parts of a newspaper. It requires a sound knowledge of language so as to spot faults, an unswerving dedication to accuracy, taste and legal fitness, an ability to collate from various sources a story of required length and style, to rewrite copy swiftly as and when required, to provide a readable and meaningful headline that fits, and to do all these things coolly in the face of deadline pressure.

The fact that, on some papers, making up pages on screen and even designing them, may fall to the same sub who edits the text is a measure of the technological change that has come over editorial production.

The arrival of Quark

The use of the computer in newspaper production which started in America in the early 1960s and spread across Europe had, by the mid-1980s, freed Britain forever from the centuries-old dominance of hot-metal printing. For the first time, journalists could generate their own type effortlessly as they sat at their keyboards writing and editing the text that went into the newspaper. In fact, it was the writers, as they keyboarded their stories into the office computer for editing, who effectively set the newspaper in type.

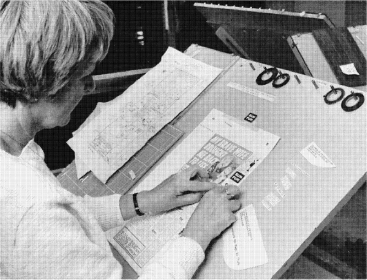

The computer, in this new production mode, allowed pages to be made up photographically, hence the term photoset type. Text and headlines were typeset and output on bromides; these were cut up by photo-compositors with scalpels (Figure 6) and attached to a page card in accordance with a page layout supplied by the editorial. Pictures were laser-printed on to bromides and likewise put into the page and trimmed by scalpel as required. The adverts arrived in the composing room as page-ready bromides and were pasted into position. When complete, and after being copied for inspection by the editor and advertising manager, each page was photographed and the negative sent to the platemakers to be made into a printing plate. It should be said that this system of page production is still in use in some newspaper offices.

Figure 1 The leap into full-screen composition. Apple-Mac page-making terminals in use at the New of the World before the introduction of their Windows-based Unisys Hermes system. Make-up here is using the QuarkXpress program, but with separate subbing and page-building screens

Since type could be set and corrected hundreds of times faster than on hot-metal Linotype machines, and the pages put together much quicker than by the old method with its heavy metal type, the new photoset type and cut-and-paste makeup gave newspapers instant benefits in speed, safety and cost saving. Moreover, through interfacing easily with web-offset presses through the use of transfer-image polymer plates instead of direct-impression metal ones, the photo-produced pages enabled colour to be used for the first time in run of press.

The change, through the loss of traditional printing jobs, also brought to an end the years of confrontation and bad labour relations that had existed between managements and the old print unions, and resulted in the move of long-established newspapers from city centres to purpose-built premises in suburban locations with rooms full of keyboards and monitors and a press hall with banks of new web-offset presses.

But a revolution in newspaper production as big, or bigger, was round the corner. Hot metal and traditional typesetting had gone; the old rotary presses, with their heavy direct-impression metal plates had gone; the computer reigned supreme – but there was still a composing room, still camera operators and a dark room used in page production.

In the early 1990s a number of national papers, both daily and Sunday, began experimenting with page composition on screen. They used Apple-Macintosh desktop computers via a page make-up program called QuarkXpress which could be linked with the office mainframe computer, in which text was stored, by means of an interface. It was not trouble-free but it did enable pages to be put together on special make-up screens. Subs were selected to take charge of this new function, while text editing continued as before on the older editing screens.

It was then found that Apple-Macs used in clusters and driven by powerful file servers had the speed and memory required to handle complex layouts on screen without reliance on a mainframe database. Moreover, the new method accepted text and graphics inputs on page more easily and allowed the subeditor in charge of making up the page, using the Quark program and mouse controls, the flexibility needed to build to any nominated style. Full electronic pagination had arrived.

Primitive page-making systems offering formula pages had been around for years in some provincial papers, but they lacked the speed and memory, and also the flexibility, to produce pages of a variety and standard acceptable to the bigger national papers. There was a continuing problem with graphics generation in the computer. The harnessing of QuarkXpress and Apple-Mac desktop computers, plus developments in servers, picture scanning and imaging, especially in colour, solved these problems.

By 1995 all the national dailies and Sundays had adopted the Apple Mac-QuarkXpress solution, through a variety of configurations, and had moved into full screen composition. The composing room was no more. The dark room still played a role in the creating of high resolution page negatives required as an interface between screen and plate, but the arrival of direct-to-plate programs began to phase out even this. By 1998, a number of national newspapers made up on screen were delivering pages straight to the platemaker at the stroke of a key.

The incentive towards page-to-plate production in the nationals stemmed from the move, for distribution purposes, into decentralized printing at provincial sites since it simplified and speeded up the transmission of pages straight to the press. At Canary Wharf, in East London, where seven national papers owned by Mirror Group Newspapers and the Daily Telegraph, were published there were no presses at all. The papers were printed in a variety of centres including some abroad.

Meanwhile, in the provinces the move was towards concentration of printing on fewer sites as companies and papers replanted and merged their interests, which included contract printing for the nationals. On the editorial production side, provincial papers were less advanced. While the bigger ones had introduced the latest screen make-up systems, more than a quarter of titles were still using cut-and-paste in the middle of 1998.

‘Subs with Quark experience’

Screen page make-up is still new and novel enough for its effect on editorial production to be over-stated by those in awe of it. Advertisements for subs request ‘experience of using QuarkXpress.’ In fact, senior subs, wearing their production hats, have always been responsible for page make-up, whether the work entailed guiding the inky hand of an old-time stone hand or the scalpel of some newly trained paste-up compositor. The advantage of screen make-up is that the subeditor – and not an intermediary – now does the moving about of ingredients and the polishing of space. The journalist is in charge of the product.

It is not an arduous job. The page plan, originating as ever as a ‘rough’ drawn on a sheet of paper by the executive concerned, is blocked out on the screen in the type style of the paper, with the contents indicated. Stories are called up ready subbed to fit their space. Pictures and graphics are imaged into their boxes from the scanners and adjusted on screen for a fine fit. Adverts are likewise called into their boxes and given a tweak. Mouse and key controls are instantaneous. The work of putting the page together is easy compared to what it used to be.

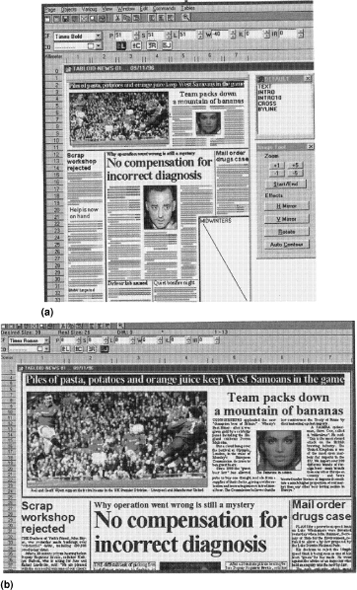

Figure 2 A page on screen (with zoom section), using the Unisys Hermes pagination module. It provides for WYSIWYG composition, continuous object and status monitoring and image cropping on page. Multi-user access allows several people to work on the same page

Sub or page editor?

What is the effect of this new situation? The speed of technological change has produced some weird ideas. Should subs be left to design their own pages (as they have always done on many weekly papers) as well as edit and typeset the material? Have subs, as a result of technological change, mysteriously less subbing to do than they used to have?

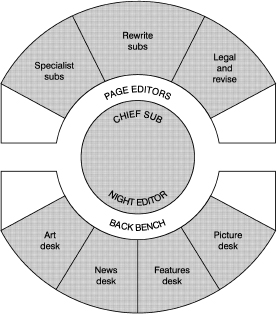

Should the subs’ table be redesigned as what someone has called the ‘command desk system’, with the editor in the middle and executives, page builders and the rest of the subs in declining order of importance ranged around in concentric circles (Figure 3), with a ‘rolling conference’ going on all the time – a daunting intrusion into the peace needed for editing?

Should there be ‘page editors’ who each take a page on to their screen and sub every item, be it a feature or a news item, be it political or be it some sexy scandal, be it a crusty columnist or a clutch of readers’ letters? Alternatively, should newspaper editors – as The Independent tried briefly to do in 1987 – let writers edit and project their own material and get rid of subs altogether?

Figure 3 The command desk system of editorial production: it aims at centralizing edition inputs and decision-making, with direct back bench control of make-up through designated page editors working with specialist and rewrite subs

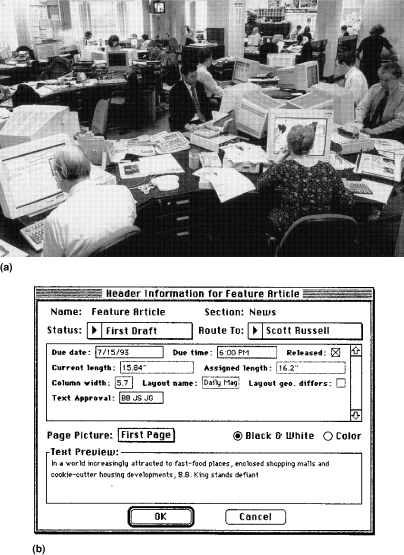

Figure 4(a) Pages take shape on Apple-Mac screens at the Nottingham Evening Post, which utilizes the Quark Publishing System (QPS). Subeditors are using the zoom facility to work on sections of pages. The latest version of this system extends QPS applications also to the Windows market for use with PCs equipped with Windows 95 and Windows NT. (b) Tracking the material – an information header for a news story or feature is created on the Quark database server and filled in by users as the feature moves through the editorial and production processes

Technology and the sub

Developments in technology are pointing the way to the future. The early Apple Mac-QuarkXpress solutions – which can still widely be found – were hybrids in which problems of interfacing with ageing editing systems and databases meant that page building and text editing had to be done on different screens.

Improved applications which entailed the use of clusters of Apple-Macs driven by powerful servers, which did not have to rely on the mainframe, speeded up both editing and make-up and allowed subs to edit on-page. Later, integrated Apple Mac-QuarkXpress systems, such as QPS and, more recently, the Microsoft Windows-based Unisys Hermes system, brought with them improved on-screen graphics handling and vastly upgraded and faster database management. These systems integrated make-up and text editing on every workstation in the editorial department if it were so required.

Hermes, the first fully-fledged solution not using Apple Mac computers and QuarkXpress, offered papers, and groups of papers, a powerful constantly updated text storage and retrieval system delivering through new-type servers. It had a multimedia archive which claimed Virtually no limits on the type of data that can be stored and manipulated’ which was aimed at companies moving towards electronic publishing via the Internet.

It also worked on any standard PC running Microsoft Windows 95 by means of text handling, design and make-up, and image handling modules, and could be customized to any size of operation, including multi-format papers on the same site.

While facilities in the new systems introduced might make subbing on a ‘whole page’ basis through page editors seem logical, the reasons for doing this were less so. Specialisms for many papers, especially those selling strongly on text as opposed to display, relied on special skills and experience, on subs who were good at such things as captions or rewrites. With the new systems, multiaccess, in fact, allowed any number of subs to work on the same page – which they could all have on-screen at the same time – so there was no problem. Specialist subs could fit in the bridge column or a technology report. Chunks of artwork such as blurbs could be taken out of the frame to be worked on by an artist and returned page-ready, while simultaneously a sub might be grappling with a long-running story as the lead.

The page deadline, however, required that one sub – or a production editor? – should be responsible for deciding when it was ready and, in this respect, nominated page subs or page editors made sense.

Figure 5 Picture editing on screen with Unisys Hermes. Their NewsCrop tool allows cropping, mirroring, zooming and adjusting tonal curves in mono and colour, enabling quick last minute changes to be made. The system permits the integration of applications such as Adobe PhotoShop if additional image handling is needed

Other changes blurred the old boundaries in editorial production. By 1998 some newspapers, despite their scorn of the early modular make-up systems, had begun setting up page ‘modules’ that could be called up and adapted on screen for fast routine pages, thus reducing the work of layout artists, whose graphics role had already been reduced by computer-generated graphics. More imaginative designs and ‘spreads’ still required an art desk, especially on the big national papers.

In another development some national and provincial papers announced contracts for agreed plate-ready pages of news from PA News’s new page production team to supplement their copy input. The attraction for provincial papers – the Liverpool Post was one – was that they obtained coverage, set up in their own type format and fitting round the adverts, of national and international news that was outside their normal staff deployment. A number of national papers used the arrangement to input made-up pages of agreed regional content, including some sport, for edition areas where they were not well represented. While the agency contracts could be used by some papers for cost-cutting they led, in fact, to more jobs for subs at PA News who built up their editorial production staff as business grew.

All these developments were spin-offs of the all-dominant computer which had moved into the centre of editorial production. Which ideas you used and how you used them depended on the sort of newspaper you were, and what you were trying to do.

If the editing and presentation of text and pictures and their projection and targeting on the readers were important, as they surely are on most newspapers (and if you are not trying to run entirely on a shoestring), you needed specialists with skills in these areas. They are not, for instance, matters that can be left to reporters or features writers, whose skills and techniques are for different ends. The working time of those staff is best spent gathering and writing news and researching and composing features – things that chair-bound subeditors might not be very good at.

There is no doubt that involvement in page make-up, which is a very computer-organized and not intrinsically difficult task, has made life more interesting for subeditors. When, in response to your cursor and mouse control (if the task falls to you), you see a page taking shape on your screen in a way that it will appear to the readers, you feel far closer to your newspaper. Apart from this, however, the techniques of editing and projecting the contents of your newspaper to the readers have not mysteriously changed. As subs, you have simply been given better tools with which to do the job. This should make for better newspapers and probably more of them if proprietors and editors get the formula right and are prepared to maintain standards.

Figure 6 Halfway house: the cut-and-paste method of page composition. A compositor attached cut-up text and picture bromides to a page grid. The page was photographed to create the negative from which the printing plate was derived. Note the stick-on tape rules that had to be used. This method has now mostly given way to screen make-up

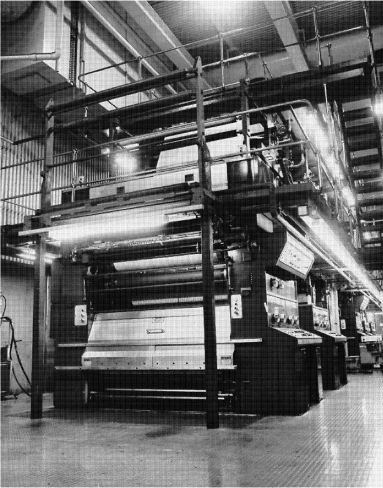

Figure 7 A cleaner environment: smooth polymer plates are used on this modern web-offset press at the News Centre, Portsmouth, where once all was hot metal. The pages are printed by being offset via a ‘blanket’ which picks up the ink by chemical means and transfers it to the paper

It is to these techniques that this book now turns.