DEALING WITH PICTURES

DEALING WITH PICTURES

Dealing with the illustrations, as with text and headlines, is a crucial part of page planning and editing. Photographs of the right subject, size, shape and quality have to be selected and presented to the reader; where appropriate, graphics and diagrams have to be provided.

Subeditors working on pages cannot detach themselves these days from the picture content. Selection and quality assessment might begin at the picture desk but, having been chosen, a picture is still subject to editing. Editing begins at the art desk, or at the scanning studio. Here, pictures are cropped, sized and retouched in the scanner, colour corrected where necessary, and imaged onwards into their page boxes (Figure 27). On screen they are further adjusted in shape and size by the sub, using mouse controls, until they best fit the space and ideas of the page design.

Figure 27 A New of the world page on-screen awaiting two pictures

There can be variations of this routine. Where pages are being built on master screens, the art desk might carry out the picture function, not only scanning, colour correcting and delivering pictures and graphics to the page but adjusting them to fit, while the subs deal separately with text editing. The art desk, working with the back bench, remains responsible for page design on bigger papers, preparing detailed layouts, either directly on screen or from paper to screen, and passing them down to the editing screens for the pages to be made up by subs or page editors, where so designated.

Smaller papers make greater use of multi-skilling. A sub might be given responsibility for choosing the pictures, cropping, sizing and scanning them, designing the page and subbing the contents. There are miniaturized scanners for worktop use by subs for this purpose. On such papers multi-skilling in editorial production has always been accepted. The computer and the make-up screen and modern scanners have merely made it easier and faster.

Whichever the route – and systems are constantly being updated – pictures and the captioning of them (see pages 171–4) are very much the concern of the subeditor.

Role of pictures

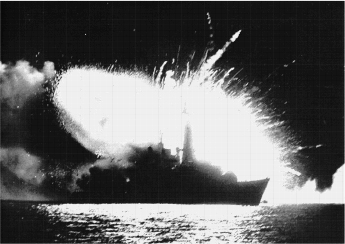

The notion that a good news picture is worth a column of words does not altogether hold true. There are few pictures that can stand without text whereas the text regularly stands without pictures, although there are occasions when it badly needs them. Famous news pictures such as St Paul’s Cathedral against a wartime background of flames, the shooting of President Kennedy, and the frigate Antelope in the midst of a fireball in the Falklands War (Figure 28), remain in the mind long after the words have faded. This is what really tells the story, the picture enthusiast will say. But on their own such pictures cannot, and do not. They have to rely on the context of words, on explanation, in the same way as tele-film relies on the commentary and the presenter’s guidance.

The better and more dramatic the picture the greater is the danger of readers (or viewers) being misled by their own heightened reaction. Shorn of its context of words and explanation a picture can, in a real sense, lie or at least fail to deliver the truth.

A national paper reporting some years ago on the horrors of the Biafran war in Nigeria carried a picture of an emaciated pot-bellied child as a pictorial indictment of the perpetrators of the fighting. The child was not identified but it transpired that the picture was from another African country. It achieved its objective in bringing home its message to the reader, one might say.

This is true but the picture was nevertheless lying. Placed as it was, it misled the reader into thinking it arose directly out of the war, for it did not have the necessary explanation of its origin, If, because the intention seems to be worthy, this sort of practice is condoned, where does one draw the line in planting pictures to condition reader response?

With the digital ‘correction’ of tone and colour in pictures by which the pixels representing the screened dots of the image can be moved about in the scanner, the danger of misrepresentation in picture content is much greater. The growing number of complaints to the Press Complaints Committee about image manipulation and some celebrated recent cases have demonstrated this. The Commission’s Code of Practice for the Press does not specifically mention image manipulation but it does say: ‘Newspapers and periodicals must take care not to publish inaccurate, misleading or distorted material including pictures.’

Yet notwithstanding the possibility of misuse, a newspaper would be less informative, less complete and less attractive without pictures. They not only supplement the text; they enhance and extend it by highlighting and pressing upon the reader important parts of it; they make it easier for the reader to build up a picture of what is being read.

Figure 28 A photograph that made news: the famous Reuters picture of the frigate HMS Antelope exploding into a fireball after being hit by an Excocet missile in San Carlos Bay in the Falklands War

News pictures in a newspaper have a permanency and graphic effect denied to television film, which has a fragile grip on the senses and a low level of recall. Colour is now widely used, and mostly very effectively, but being in black and white can often increase the drama and tension in news pictures. It has to do with the basic unreality of the colour range that systems give compared with the nuances of tone and texture in real life. Black and white plays upon the imagination and reconstructs reality in the mind whereas colour can be bland, although it can have visual impact when used for the right pictures.

Pictures also serve another function. They form distinctive eye-catching elements that trap the readers’ attention. The position of pictures in relation to the contents of a page is thus part of the balanced visual pattern by which the newspaper content is projected. We can say, in short, that a picture performs two functions:

1 It illustrates the text.

2 It forms an element in the page design.

Picture sources

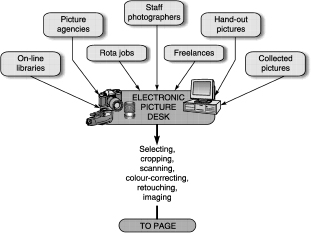

Taking, collecting and providing pictures is organized on similar lines to the newsroom operation. It revolves around the picture desk, which works closely with the newsroom and the picture library. Directing this task is the picture editor or (on small papers) the chief photographer (see Figure 29). The picture editor keeps a schedule of pictures that are wanted or expected and briefs photographers about the paper’s requirements and deadlines. The photographers might work alongside reporters on a job or act independently, depending on time and the sort of job. If a staff photographer is not available the picture editor has to look to other picture sources.

Figure 29 How the pictures flow: the part played by the electronic picture desk in routing pictures from their source to the page

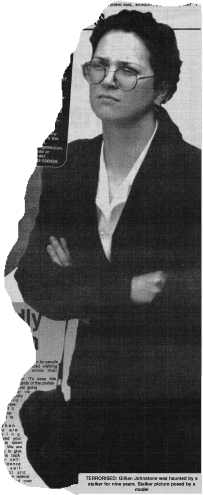

In handling stories that have pictures, whether colour or mono, you should make clear their relevance to the text in a caption if the reader is to be correctly informed. No picture should be left without explanation or clear identification. Even a specially taken ‘mood’ shot accompanying a feature can raise doubts or misconceptions in the reader’s mind if it is uncaptioned (see Figure 30).

Staff photographers

Staff photographers working from head office or branch offices, or sometimes operating independently in a district, are the main sources of exclusive pictures and can be more easily deployed alongside reporters on jobs where on-the-spot pictures are wanted. They are journalists by training and definition and their approach and job briefing are in line with that for reporters. They share the same deadlines. Their numbers might vary from four or five on a small paper to perhaps twenty or more on a big national daily.

This is an area in which technology has brought about huge changes both in cameras and picture transmission. Says Martin Keene in his book Practical Photojournalism (Focal Press): Print transmitters have been replaced with negative scanners and laptop computers. It is possible to transmit pictures from almost anywhere in the world into the network of computers used to make up a newspaper. Some newspapers no longer have darkrooms; once the picture has been selected [from a transmitted set] the negative is scanned into a computer and the first time it is seen as a print is when the newspaper comes off the presses.’(See Photo briefing, page 55.)

Staff pictures become the newspaper’s copyright and syndication or reproduction fees are earned if they are used in other papers. Photographers, even when working with reporters, are responsible for their own caption information and fact and name checking.

Figure 30 Even a mood picture needs a caption, especially where a model has been used in setting it up. The caption on this Birmingham Evening Mail picture of a girl plagued by a stalker makes it clear that the person shown is a lookalike

Freelance photographers

Freelances provide some picture input but, except for high-fee exclusive work for which they hold copyright – such as the much criticized paparazzi who snatch pictures of the famous or specialist areas such as glamour – their contribution is usually by daily, weekly or holiday relief arrangements, or for one-off jobs. In provincial areas local newspaper photographers might work as regular accredited freelances for bigger papers, being paid an annual retainer fee and a fee for each picture used.

In the more specialist areas of glamour, sport, animal and technical photography there is a good income to be earned by freelances who become known and to whom newspapers, and more especially magazines, turn to at times of need.

Picture agencies

Picture agencies provide a great range of photographs for use and stock, especially from overseas, on a contractual basis to subscribing newspapers. Such ‘service’ pictures, though lacking exclusiveness, usefully fill gaps in coverage. Agencies, specializing in such areas as sport, political or celebrity portraiture, usually charge a fee for each occasion of use. Occasionally they will part with British or other reproduction rights for a higher fee.

Rota pictures

Agencies are sometimes relied upon where only limited picture coverage of an event is allowed. Royal or certain political occasions, or even celebrity photo-calls where a large influx of press photographers is not convenient, are sometimes on rota. The arranging is by a committee drawn from picture editors of the various newspapers and agencies who subscribe to the rota, and it has a permanent secretary who keeps a list of those entitled to camera facilities. From this list newspapers and agencies take it in turn to cover rota jobs, on which anything from one to maybe seven photographers are allowed. The resulting pictures are made available for use to the newspapers contributing to the arrangement.

Collected pictures

In some news and features jobs pictures might be supplied by the subject or organization concerned. Permission is needed to use such material and any possible right investigated.

Hand-out pictures

A good deal of the material used on TV programme pages and showbiz stories is supplied free to newspapers from film-making and programme companies. Free pictures often accompany hand-out material where the aim is to seek publicity in a newspaper or magazine.

Picture libraries

Pictures libraries and archives, now mostly on line, supply pictures for a usage fee, and sometimes also a research fee. The main library source is usually the newspaper’s own indexed picture files of news events or people who have been, or are likely to be in the news, going back as many as twenty or thirty years. These sources are used where ‘head shots’ or recent likenesses are needed with stories, or when an event comes back into the news, or if ‘flashbacks’ are need of similar events. The office’s own picture files are also a useful check source for identification and personal details.

The photo briefing

The picture editor knows from the daily news schedule and the editor’s conference the nature of each picture job and whether there is a need for a specific shape or sort of picture, or the inclusion of certain wanted detail.

Technology has leapt ahead in press photography and has helped to make some formerly difficult assignments easier. Long, heavy telephoto lenses for which the help of an assistant was needed are a thing of the past. The use of mirror lenses for press work, by enhancing the image magnification, has effectively halved the length and weight. They also increase the amount of light reaching the film, making for a better quality picture, The focal length of telephoto lenses can be doubled by the attachment of a powerful supplementary lens, while the use of an electronic booster between the lens and the film, by picking up the light at the red end of the spectrum, makes it possible to take pictures in almost total darkness.

The automatic pocket-size 35-millimetre cameras used for rapid clusters of shots in varying conditions are now being replaced by filmless digital versions, while the electronic picture desk (EPD) (see Figure 29) has become the normal interface between incoming pictures and the newspaper’s production process. With advances in miniaturized transmitters, films can be developed on location and transmitted by telephone line by means of a modem, including in colour, so that they reach a newspaper’s EPD in minutes. Modern transmitters transmit directly from the negative, reversing the image so that the picture is received in positive. It is possible with another device to take good prints from video film which make acceptable pictures for newspaper use.

Today’s trend is for greater use of telephoto lenses of up to 400 mm, and occasionally up to 1000 mm, in order to concentrate on people and actualities, and there is less scope for the composed mood shots beloved of Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson and, in recent decades, Don McCullin. With today’s equipment comes the opportunity of exploring the unusual angle which can enliven the page – what Harold Evans calls ‘the yawn in the crowded political meeting rather than the candidate in the centre of the waving crowd.’

In news pictures it is people and actualities that hold the attention of readers, with animation and a good likeness rating high. This is nowhere more important than in the scenes and faces photographed for a local paper (see examples on pages 19 and 22).

News pictures are usually of two sorts:

1 The action shot which helps tell the story.

2 The picture that shows people, which might simply inform.

The first is more prized and is harder to catch since there might be only one chance. The second can be set up simply by the photographer asking people to take up positions. Here, the danger of a cliché picture arises, especially if the photographer is overworked or rushing from job to job. Yet ingenuity can produce an out-of-the-ordinary composition.

In big events such as State funerals, Trooping of the Colour and festivals, prearranged shooting positions and the lack of mobility make timing of the essence in getting the wanted picture. In indoor work the effect of the flash on the subject is the perennial hazard, plus the problem of shadow and small room perspective. Here a wide-angle lens is useful.

The skill of the picture editor lies in taking account of the various hazards when briefing for special requirements. It is from the set of contacts produced that the picture editor, looking for sharp detail and good composition, selects the frames for enlargement so that the best pictures are available from each job for the pages being planned.

Here again, technology has stepped in by devising programs that digitize and store incoming pictures on magnetic disks from which they can be recalled on a monitor screen and examined for choice. A picture chosen need not even be printed; it can be cropped, sized, colour-corrected, electronically retouched and imaged straight on to the make-up screen.

Choosing pictures

Even without stock sources, newspapers get many more pictures each day than they can use and a selection process takes place similar to copy tasting (see Figure 31). This is usually done by the picture editor but it can fall to the subeditor dealing with the page, particularly on smaller papers. In such a situation, you should take the following points into account:

Content

Does the picture show the right people and scene? Is it a good likeness? Does it capture the action, and is the background right? Does it properly complement the story and extend its content?

Composition

Do the grouping and position of the people in relation to the elements of the picture form a pleasing shape? Is it the most eye-catching of the pictures that have the required subject content?

Balance

Will the content balance visually with the rest of the page, including the advertisements? For instance, ‘head’ shots should not look out of the page or away from their story. Also, clashes with other picture content should be avoided. A picture of an ocean liner will look superfluous against an advert also showing a picture of a liner. A picture showing the heads of a man and a woman would lose effect against an advertisement with the same sort of picture.

Tone

Has the picture good tonal values? Is there sufficient contrast between dark and light tones so that it will reproduce adequately, bearing in mind that more parts of newspapers are in black and white than in colour, and newsprint is nowhere near as kind to detail as glossy bromide or gravure. A lack of dark or light tones can result in a grey effect which blurs detail on printing.

Stock pictures

A temptation in using stock pictures is to condition the reader by selecting one that shows a person in a particular light – the grim face of a strike leader, the smug or triumphant expressions of politicians, or pictures that send up well-known people by catching them in an unguarded moment. The choice might seem fitting for the accompanying story, but there is a line beyond which the display of foibles and character can become bad taste or propaganda, or even libel if a person is really made to look stupid, as lawyers are willing to demonstrate. Subeditors selecting pictures from stock should beware of this.

Editing pictures

Few photographs are used in a newspaper exactly as they are taken. A picture might have detail irrelevant to the story it accompanies. This might be because of difficulties in taking the picture. Perhaps it includes people who have nothing to do with the story, or maybe the page visualizer wants to accentuate part of the picture, or exclude part of it for reasons of news value or legality. This selecting and excluding parts of a picture in the course of achieving its required shape in the page is called cropping. Cropping is an essential part of editing a picture – but first a few words about this contentious subject.

Cropping can arouse violent disagreement and much pontificating by experts who think it should have been done differently, or not at all. A good picture, it is said, is its own advocate. This is true if the picture is being used for what it is and not for what it is required to do, as for example in publishing a new royal portrait. Not many pictures fall into this category.

A newspaper is not just a vehicle for the camera. The requirements of picture display, however attractive to the eye and justified by picture quality, have to be balanced against the demands on space by the news and features coverage to which the paper is committed by its style and market. It is in detail of information that a newspaper scores over picture-dominated television both in editorial content and in advertising.

Figure 31 Choosing for the page: what makes a good picture

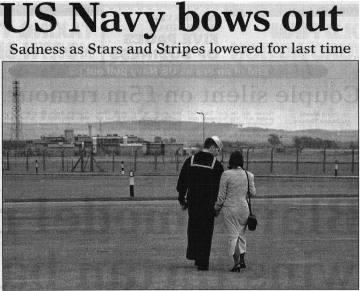

![]() The Aberdeen Press and Journal photographer went for mood in the shot, opposite, of an American sailor and his Scottish wife at the lowering of the Stars and Stripes at a Scottish base

The Aberdeen Press and Journal photographer went for mood in the shot, opposite, of an American sailor and his Scottish wife at the lowering of the Stars and Stripes at a Scottish base

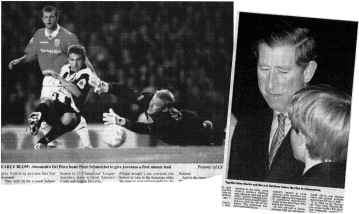

![]() The shot a sports photographer hopes for. The theme is action in the Western Mail’s Allsport picture of Juventus scoring a goal against Manchester United in the European Champions’ League

The shot a sports photographer hopes for. The theme is action in the Western Mail’s Allsport picture of Juventus scoring a goal against Manchester United in the European Champions’ League

![]() Expression is the theme of this well-caught picture in London’s Evening Standard of Prince Charles and his son Prince Harry about to fly off on a Royal tour

Expression is the theme of this well-caught picture in London’s Evening Standard of Prince Charles and his son Prince Harry about to fly off on a Royal tour

An experienced photographer knows when he (or she) has got a good picture in terms of light, composition and content. The way the picture is cropped and used on the page and the significance with which it is imbued has to obey additional parameters such as the words of the text, the space available and the requirements of page planning.

The aim is to avoid wasted grey areas while at the same time emphasizing required detail (see the crop in Figures 32 and 33). Thus in a picture showing a group of houses in which context is of no concern, a house might be selected because it is the one with which the story is concerned. A person taken from a group picture might be cropped from the waist upwards because that is what the visualizer wants. The same agency news picture might appear in rival papers cropped in different ways because of different ideas in projecting a story.

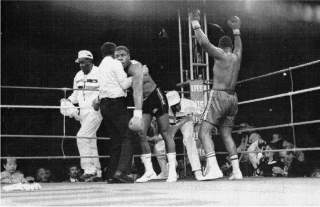

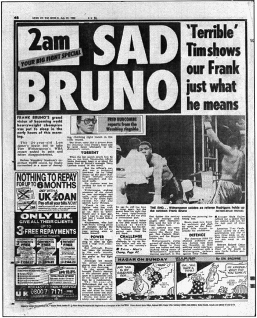

Figure 32 As taken at the ringside: News of the World cameraman Brian Thomas captures the moment of triumph in a big boxing match

Figure 33 The picture as it was cropped and used to show the two fighters in close-up

The editing of pictures to prepare them for the page has been both simplified and speeded up under modern systems. There are four stages in the process, although on smaller papers some might be merged:

1 Assessment for quality and suitability.

2 Cropping and sizing for shape.

3 Retouching.

4 Fitting into the page.

Here is what happens on a typical well-staffed national paper.

Assessment

The picture editor – with the benefit of an electronic picture desk (EPD) these days – examines on a monitor screen the contacts transmitted digitally from the photographer or from other on-line sources, and shortlists a selection of the input for the back bench or other executives. The picture editor does this by reference to the quality and composition of the pictures and their suitability for the requirements of the pages. A final choice is made, either from the material showing on screen or from printouts of it, after discussion involving the picture editor and those responsible for the various parts of the paper.

Cropping and sizing

This is usually done either by the art desk or the executive in charge of the page. The picture, having been chosen, is called up from the picture desk computer and is cropped and sized at the same time on the scanner screen to give the required image. The wanted part is enlarged or reduced so that the size and shape of image produced fits exactly its pre-selected box on the page. Where the task is left to a scanner operator, the cropped area and size required are usually marked for the operator on a printout of the picture or of the contacts.

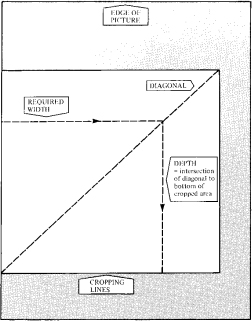

Cropping and scaling was formerly (and still is under paste-up) done manually on the back of the print by the diagonal method as shown in Figure 37 on page 66.

The shape resulting from cropping (anything other than a rectangle is not normally feasible; even a cut-out or oval would be developed from a basic rectangle) is governed partly by the composition, partly by the intentions of the visualizer and partly by the space available. Composition predominates; it is not usual to force a picture of naturally horizontal shape into a vertical. In such a case it is either the wrong picture or it is on the wrong page.

Cropping should be creative. It is a method of editing a picture for emphasis. Bad cropping occurs:

1 When the position or attitude of the subject person becomes distorted or meaningless because of the exclusion of detail.

2 When the cropped area is too small, causing a dispersal of detail on enlargement and printing.

3 When lines and perspective are thrown out by ‘tilting’ in an effort to get a wanted shape.

Retouching

Inevitably there are problem pictures. A picture of inferior, or even poor, quality might be used because it is the only one available and is vital to the story. Another example is where, despite cropping, a picture has unwanted detail such as someone’s head which has nothing to do with the story, or heavy tones of wallpaper which clash with a person’s features.

This used to be the area where a retouching artist with an airbrush was called on to ‘improve’ the picture, occasionally with indifferent results. Today, programs such as Adobe PhotoShop are achieving, with electronic retouching in the scanner, effects far better than the best possible results produced by the old retouching artists. The method, however, entails changing the ‘pixel’ structure of the picture’s image, which can lead to ‘image manipulation’ and even invention of detail. This has led to tighter editorial control over retouching to avert lawsuits that can follow tampering with pictures.

In some cases a picture might be reversed (i.e. printed from the negative back to front), so that people are not looking out of the page or the story. This is a dangerous practice unless the detail is carefully studied. Readers are good at spotting coats buttoned the wrong way, wedding rings on the wrong hand, or hair parted on different sides in different papers. More bizarre results are right-hand drive cars turned into left-hand drive and number plates reading back to front.

Fitting in to the page

In full screen make-up it falls to the sub in charge of making up the page to check and adjust, and even if need be to enlarge or reduce the image, after the picture has been imaged into its box from the art desk or scanning studio. By mouse controls the box size, and therefore the picture size, can be varied on screen, and even tilted, if layout changes demand it at make-up stage. The reaction to the mouse click is instantaneous, and the speed and degree of control give the page sub great flexibility at edition changes, or if the layout or space has to change during page make-up.

The pace and ease of page building with mouse controls has widened the role of subs on smaller papers. On tight staffs, and with formula-based pages it is common, as we have seen, for a sub looking after a page to design it, choose, crop and scan the pictures required, sub all the stories, and build the page on screen up to plate-making readiness. On the bigger national papers the greater specialization practised in editing precludes the use of this degree of multi-skilling.

The design function

The needs of page planning can influence the choice of a picture and its shape and size. Since pictures, as we have said, form part of the visual pattern of the page, it is usually desirable to have one main illustration with perhaps a number of small ones, or maybe no others at all. The choice of the main one has to be made at the start for it governs the design.

The best available picture for visual effect may not go with the main story. It might be with one of the minor items or be covered by a self-contained caption, and be chosen in the absence of any usable picture with the main items. The visual balance of the page thus becomes a factor in picture choice. The main picture is a focal point in this balance, its position being influenced by the relative visual mass of advertisements, main headlines and text. Newspaper pages reproduced in chapters one, two, eleven and twelve of this book show this factor at work.

Taking our explanation further we can say that the inclusion of a story on a page can be because it provides a picture which helps give visual balance as well as illustrating the story. It is not usual to have two stories with good picture coverage, leaving none for another page. An exception would be a page of news-in-pictures. Only where the editorial space left by the advertisements is very small would the page executive not bother with illustration.

Visual effect can become an obsession with tabloid newspapers, including some provincial ones, where display can starve the pages of reading matter if pushed too far. A balance should be struck between pictures and text so that the functions of illustration and visual balance performed by pictures are utilized and a newspaper, while making itself attractive, does not become a slave to its design and short-change its buyers of reading matter.

Uses of pictures

Where a certain type or shape of picture is expected to be used it is usual for the picture editor to brief a photographer with such advice as ‘a strong double of this,’ or ‘go for a wide shot – it’s the heads that matter.’ The worldly camera-person, who is planning a cluster of shots using a digital automatic, will probably go for a variety of shapes and angles for good measure so that there is a choice should the advertising department leave the editorial an awkward space to fill, or a story and its picture be moved to a different page.

Nevertheless, the picture finally chosen will determine by its composition, and what is required to show, the shape it takes in the page. In fact a picture that is considered to be worth a good space, whatever pre-conceived ideas might have been held, will be given a page where this is possible. Its shape and size will govern the disposition of stories and headlines around it. It will become a fixed point in the design to which the other elements adapt, although it still has to fulfil its function of informing the reader since it is part of the day’s input of news.

If a number of pictures are used together on a news page, a sequence (Figure 15 on page 34) is better than a montage, the coupling of pictures into a display pattern, with complicated cutting in (Figure 34) since it is less troublesome and time-taking. It also looks less contrived. Screen make-up – and even paste-up – has made a great variety of display ideas possible but for news there is nothing faster or more urgent than a well-cropped, good-sized, perfectly toned rectangle.

Found more often on features pages is the cut-out in which part of the picture is highlighted by being cut away from its background to reveal the outline of a head or building or other salient feature (see Figure 35 and examples on pages 198–9). Display advertisements often make good use of cut-outs, with bastard measure text spilling round strange outlines, an effect produced effortlessly with mouse-controlled computer setting.

Pictures are also used as parts of a compo (or composite illustration) along with headline type, sometimes reversed on to colour, and occasionally line graphics. This is a fussy, though eye-catching, device much favoured for blurbs (examples on pages 62 and 212) used in features pages and often in colour on page one to signal inside page contents.

On news and features pages a simple but significant picture subject might be used as a small bleach-out, in which the image is over-exposed in the processor until it loses intermediate tones and takes on the hard black and white of a line illustration. The technique is used where a motif, or series of repeating motifs (examples on page 196) is wanted to flag a long-running or special story. Examples might be the outline of a jet fighter in an air war story, Big Ben on a parliamentary column, or a winning post in a classic race report. Bleach-outs, if chosen wisely from a sharp but simple original, can have a drama a drawn motif lacks.

Figure 34 Eight diverse fashion shots are imaged together into a montage in this women’s page presentation in London’s Evening Standard

Figure 35 Cut-out pictures and bastard setting are easily achieved in modern page make-up programs. In this Evening Standard example the setting spills round the bent cane in a typical Charlie Chaplin look-back I picture

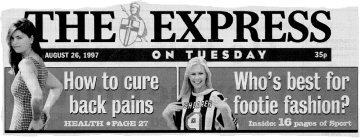

Figure 36 Successful blurbs, especially those at the top of the front page, are best achieved by a composite of boldly presented pictures, headline type and cross-references printed in colour. In this example from The Express, attractive girlie cut-outs, one extending into the masthead area, take the eye. Headings and cross-references are here reversed on to red and blue

Figure 37 Cropping and sizing a picture on the back of the print by diagonal method before shooting it for the page. Nowadays, under full-page composition, photographs are cropped in the scanner at the outset. The crop and size can be further adjusted on screen, if need be, by the page editor

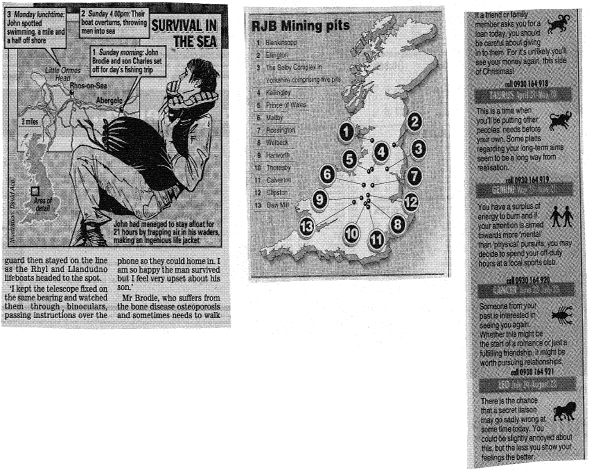

Figure 38 Jobs that graphics can do:

Top left: In this working graphic, a Daily Mail artist shows the method by which a man survived in the sea by turning his waders into a lifejacket. Also included is the time scale and geography of the man’s rescue The Guardian’s map pinpoints deep coal mines threatened with closure in an accompanying story about problems in the power industry

Right Symbol graphics – an example from the Western Mail’s horoscopes column

Reproduction of photographs by the half-tone process, in which the tones are rendered by means of tiny printed dots of varying density, still applies in web-offset printing used with computerized systems both in colour and black and white. Pictures are printed, in effect, through a fine screen (as they were in the hot metal process), though with the use of smooth polymer printing plates on web-offset presses an even finer screen is possible, giving greater clarity of reproduction in the modern newspaper.

Graphics

Graphics, in newspaper and magazine parlance, means any drawn visual aids as opposed to photographs. It was originally limited to the use of design symbols to explain statistical material – little people and half people signifying voting intentions, petrol consumption, Budget benefits, etc. – and examples of stylized ‘idiot’graphics have been available for years in Letraset and other stick-on types.

The greater use of trained layout artists in recent years on the bigger newspapers as well as on magazines has led to a boom in in-house graphics as illustration, especially on the quality Sunday papers. There are occasions when a drawing can get closer to a story’s actuality than a photograph. Tabbed diagrams can show methods used by an escaping convict, the infiltration of terrorists, or the opium trail from Thailand, in a way denied to the camera. Family trees can come alive out of the routine searches of geneaologists, the range of capacity of inter-Continental missiles and battle layouts demonstrated, and football moves and golf strokes shown in detail.

Graphics can combine with half-tones by juxtaposing tabbed identification panels alongside a picture, demonstrating with arrowed lines the path of a bullet or the route of a careering vehicle, thus extending the text.

These examples are what might be termed working graphics (see example in Figure 38). Symbol graphics still have their place. Drawn or bleached-out motifs are used to label a column or flag a long-running story such as an election or a big strike. They abound on holiday supplements, the logos of well-known columnists, TV programmes and racing cards – a silhouette here, a pair of sunglasses there, the scales of justice, and so on. They give easy recognition to regular features and looked-for parts of the paper. They are part of the paper’s visual character, part of its familiarity

The computer has greatly increased the use of symbol graphics (see also Figure 38), although graphics drawn in-house can be entered into the computer as stock for use as needed and will be more exclusive to a publication.