Chapter 4

Methods and Tools

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Outline the process of operational risk management starting with identifying and benchmarking risk

2 Identify and analyse risk factors and loss events and differentiate between external and internal risk factors

3 Describe the process to identify loss events, starting with brainstorming, moving to defining events, and finally screening events

4 Understand and describe the process of risk and control self-assessment (RCSA) and key risk indicators (KRI) and internal loss data (ILD)

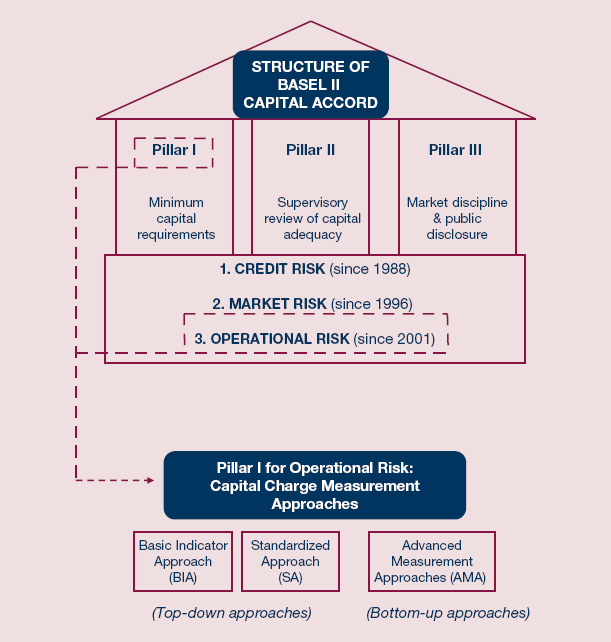

5 Understand the three-pillar structure of the Basel II Capital Accord as well as Principles 6, 7, 8, and 9 and how they impact operational risk management

Introduction

As we have seen, failures to appropriately manage operational risk have catastrophic consequences. The case studies outlined in Chapter 3 are rare and, at times, extreme events but they underline the importance of strong operational risk management. The dramatic nature of these events may hide or minimise the potential impact of smaller loss events that may happen every day at financial institutions. Depending on their frequency and severity, smaller loss events could bleed a bank slowly but seriously, a death of a thousand paper cuts. Avoiding these smaller but more frequent events is also a key task of operational risk managers and the goal of any operational risk management strategy.

This chapter starts out by examining the process of operational risk management, taking into consideration the reality that the scope of operational risk can be extremely wide. It starts out by outlining the process of operational risk management and the path towards defining incidents and loss events. Benchmarking operational risk is a process that can be divided into several clear steps, starting with identifying critical processes and resources to describing them and evaluating them against specific benchmarks determined based on the strategic objectives of the bank.

An effective benchmark requires something to benchmark against it. Managers, whether directly involved in operational risk management or otherwise, should have a firm grasp of operational risk factors and loss events. Risk factors can be found in most business areas, from the market and credit risk exposures associated with foreign currency operations to the often-unpredictable customer behaviour that impacts dealing services.

Each risk factor can lead to loss events and, here again, there are multiple categories. Loss events range from fraud—whether internal or external—to failures of execution and even employment practices. Useful processes such as risk and control self-assessment (RCSA), the use of key risk indicators (KRI), and internal loss data (ILD) are all-important.

Finally, we begin the discussion of the regulatory framework that guides the management of operational risk. This is a discussion that will continue in later chapters but it is an important one. The development of regulation on operational risk management continues to evolve. Although operational risk is as old as the banking industry itself, the process of regulating it is about a decade and a half old and serious efforts affecting Hong Kong banks are more recent than that, from the Basel II accords that came out in 1998 and were updated in 2006.

Here we discuss the three pillars that support the Basel II approach to operational risk management including minimum capital requirements, supervisory review of capital adequacy, and public disclosure as well as some of the most relevant principles built into these pillars.

The ORM process

By its very nature, operational risk can be very broad. Earlier definitions of the term tended to include all types of risk not included under market risk or credit risk. This broad approach created a very specific challenge for operational risk managers as it left them with the difficult task of determining where operational risk was found and how to measure it.1 This leads to the first practical problem that operational risk analysts and managers have to tackle: The development of an operational risk management framework that includes benchmarks for operational risk. In order to develop a framework for operational risk management, it is necessary to have a greater understanding of operational risk and of the operational risk management process.

Although there are some general principles, these benchmarks are rarely generic in nature. Rather, they need to be tailor made for every institution and should match the bank’s strategic objectives. Once the benchmark has been decided, the next step is to identify process and resource risks, risk factors, and loss events. Finally, these are categorised into meaningful groupings to allow comparisons and analyses.

At its most basic level, the conduct of operational risk management involves several activities, including the following:

- Identifying the risk: What can go wrong?

- Measuring the risk: How critical is a particular risk?

- Preventing operational losses, for example, by requiring standardised deal documentation.

- Mitigating the impact of a loss after it has occurred by reducing the firm’s sensitivity to the event, for example, disaster contingency planning.

- Predicting operational losses, for example, projecting the potential legal risks and market cannibalisation associated with a new product or service.

- Transferring the risk to external parties presumably better able to handle the risk, for example, insurance, hedging, surety.

- Changing the form of the risk to another type and dealing with that risk, for example, trans-forming market risk into credit risk by using over-the-counter credit products; transforming credit risk into operational risk by the use of margin or collateral.

- Allocating capital to cover operational risks.

Below we discuss the process of identifying and measuring risk and launch into a discussion of how to mitigate and predict risk. Later chapters will address other parts of the process, such as transferring risk, changing the form of risk, and allocating capital to cover operational risk factors.

Identifying Risk

Even the best, most careful and comprehensive operational risk management framework is useless if risks are not effectively benchmarked and identified. Because there are several categories of operational risk that require specific consideration, the process of identifying risk may require input from multiple functions across a bank and from multiple levels of management.

But, because every bank and AI is different, it is also necessary to consider both general risks and risks specific for particular operations. A bank expanding into new geographic areas with different regulations and even approaches to regulation, for example a Hong Kong bank opening branches across Mainland China, may have several layers of risk that may not have any impact on a strictly local bank in either Mainland China or Hong Kong. Thus, operational risk managers should take the nuances of their operations into consideration and should work to benchmark operational risk in a way that fits the operations of a particular bank or other AI.

Benchmarking

Benchmarking involves several steps: identifying critical processes and resources, describing critical processes and resources, and evaluating the processes against specific benchmarks.

- Identifying critical processes and resources. This requires the participation of senior department heads responsible for critical business processes and resources. During these preliminary meetings, the core process and resources for each strategic business unit (SBU) or profit centre is identified and the linkages between them captured. High-level processes are broken down into a number of generic sub-processes such as sales and marketing, deal commitment, confirmations, settlement and maintenance, and accounting, as well as support processes including legal, systems, audit, risk management, and reconciliation.

- Describing critical processes and resources. Once the core processes and resources have been identified, operational risk management staff compiles answers to a checklist of questions for each process or resource. These include:

- Evaluating against benchmarks. Once processes and resources have been identified and described, they should be evaluated against specific benchmarks. Benchmarks should be chosen according to the firm’s strategic objectives for the business. Current internal practices may be used by a mature operational group. A business unit in a turnaround situation cannot do this, since presumably those practices contributed to its problems. Benchmarking that involves comparisons with the best direct competitor would be more appropriate in this case. Benchmarking can also be internal, involving comparisons with operations within the same organisation, or functional, which compares the bank’s with similar process methodologies.

Risk Factors

After benchmarking, what then? The next step is to discover the risks that can hinder process performance and resource utilisation. To break down risk factors and loss events by processes and resources requires interviewing experienced line managers and senior supervisors.

It is best to start with neutral questions such as which factors outside their control affect the output of the process. Few people like to admit that things can go wrong on their watch, and that the reason for a problem could be in their own unit. It is important, though, to ascertain in which department the manager believes the loss event does originate and then crosscheck the response against the belief of managers in that unit. Disagreements suggest confusion about responsibilities, controls, and how the process works—all of which need to be cleared up to avert a real operational disaster. Also, a complacent “no problem here” attitude could be hiding potential disaster.

During open-ended unstructured interviews, managers should be asked about their risk priorities and exposures, as well as industry or competitive trends. This contextual information frames subsequent risk analysis. Prioritising directs attention to risk management. It is unlikely that all of the company’s risks can be completely captured, but it is possible to have a focused search for critical risk factors and loss events associated with core processes and resources.

Identifying Risk Factors

There are two types of risk factors: external and internal. External risk factors are usually price-related with (generally) direct impacts that are assumed to drive fluctuations in the firm’s revenues or asset values. Internal risk factors have indirect effects on profits and losses or asset values by changing the losses associated with particular events.

The precise choice of risk factors depends on the particular business unit, and analysts should be careful to avoid any preconceived notions of where operational risks lie. Backward-looking analysis of historical internal and external losses combined with interviews with experienced line managers will suggest factors that may drive losses in a particular process area.

In some cases, more forward-looking techniques can be used. Designed experiments can systematically identify which risk factors are most important on the output of the process. Such experiments can be used, for example, to infer how changes in the levels of staffing in different parts of the organisation affect errors, or how changes in staff incentives affect performance levels.

Exhibit 4.1 lists the typical risk factors that affect different aspects of banking operations, which are often used as inputs for operational risk models.

EXHIBIT 4.1 Business strategy and risk

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), 169.

| Business area | Critical risk factors |

| Forex operations | Market risk exposure, credit risk exposure (mainly OTC derivatives) |

| Commercial banks | Credit risk exposure, interest-rate risk exposure |

| Retail banking | Credit risk exposure, interest-rate risk exposure |

| Private banking/asset management | Exposures to change in financial markets (revenues partly driven by portfolio value) Exposure to financial market sentiment (greater portfolio activity in bull markets generates more fee income) Credit risk exposure (loans to private clients) |

| Investor relations | State of the market, number of investors |

| Planning | Market volatility, number of customers and competitors |

| Sales and marketing | Market volatility, customer demand, staff morale, number of customers and competitors |

| Underwriting | Market volatility, customer demand, number of customers and competitors |

| Lending | Interest rate volatility, customer demand, competitor behavior |

| Deposit-taking | Interest rate volatility, customer demand, competitor behavior |

| Trade finance | Economic performance, interest-rate volatility, customer demand, competitor behavior |

| Corporate finance | Economic performance, interest-rate and exchange-rate volatility, customer demand, competitor behavior |

| Payments transmission | Investment of technology, volume of business, quality of service |

| Card services | Use of technology, volume of business, quality of service |

| Financial accounting | Volume and diversity of business |

| Claims | Volume of business, quality of service |

| Premium accounting | Volume of business, customer demand, quality of service |

| Treasure management | Market volatility, corporate strategy |

| Dealing | Market volatility, customer behavior |

| New product development | Market volatility, competitor actions, corporate strategy |

| Compliance | Volume and diversity of business and regulation |

Loss Events

Once general risk factors have been identified, the next step is to identify specific loss events. This process consists of brainstorming, defining, and screening the occurrences that may damage a resource or degrade process output through higher costs, lower quality, throughput and availability, and higher obsolescence.

- Brainstorming. This involves an open-ended exploration of the potential events that could affect a particular process or the business as a whole. A variety of information sources can be tapped: internal and external surveys, line managers, business-level managers, as well as internal and external loss logs and audits. Questions that investigators should ask include: What specific unexpected events could affect the process? What direct impact would these events have on this process? What impact would they have on critical resources used by the process? How long would recovery take? What will be the long-term consequences on the firm?

- Defining. Every potential event should be well-defined, easily understood and clearly communicated. After a reasonably short time, it should be known whether the event occurred. Events are assumed to occur with random frequency and uncertain impact. They need not be independent of risk factors or other events, nor must their impact always be negative. Events should be consistently named, not only to describe them (say, PWR_FAIL for a power failure) but also some of the event structure (say, PWR_FAIL_KLN) if the power failure is in the Kowloon office.

- Screening. This next stage should reflect the objectives of the analysis—for example, capital management and asset protection would imply focusing on low-frequency, high-impact events, while operational efficiency concerns would target high-frequency, low-impact events. Typically, an event should be included if a qualitative assessment of its worst-case likelihood and impact suggests it is critical, or if the event may be interdependent with other critical events.

Categorising Loss Events

Loss events can also be broken down into categories, from the more general to the specific. Here again, the BCBS recommends banks map ILD to the first category of events.2 The BCBS definitions for each of these top tier events, help map out each one.

Each of these events and the definitions included in Annex 9 of the Basel II document of June 2006 are listed below:

- Internal fraud: Losses due to acts of a type intended to defraud, misappropriate property or circumvent regulations, the law, or company policy, excluding diversity/discrimination events, which involves at least one internal party.

- External fraud: Losses due to acts of a type intended to defraud, misappropriate property, or circumvent the law, by a third party.

- Employment practices and workplace safety: Losses arising from acts inconsistent with employment, health, or safety laws or agreements from payment of personal injury claims, or from diversity/discrimination events.

- Clients, products, and business practices: Losses arising from an unintentional or negligent failure to meet a professional obligation to specific clients or from the nature or design of a product.

- Damage to physical assets: Losses arising from loss or damage to physical assets from natural disaster or other events.

- Business disruption and system failures: Losses arising from disruption of business or system failures.

- Execution, delivery, and process management: Losses from failed transaction processing or process management, from relations with trade counterparties and vendors.

At times, a single loss event may fall under more than one category, as we could see in the case studies outlined in Chapter 3. Loss events in each category can be lead to both large and small losses and there are thousands of examples, many of which bankers have to deal with on an almost daily basis to prevent high frequency small loss events from seriously denting the bottom lines of their operations.

Large-scale internal fraud is relatively rare among banks with strong ORM and multiple checks and balances but it is very difficult to eliminate it altogether. The case study in Chapter 3, involving the French Bank Société Générale (SocGen) and its rogue trader Jérôme Kerviel could be considered an example of internal fraud. After all, Kerviel did fake order and took advantage of internal weaknesses. However, Kerviel did not personally benefit from those trades.

A case in Hong Kong in 1985 may better illustrate how internal fraud may impact a bank. The ultimate and complete failure of the Overseas Trust Bank in Hong Kong in June 1985 represented the successful completion of one of the earliest investigations by Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC). In 1985, the government took over the bank, the third largest local bank, and injected HKD2 billion (US$256 million) to shore it up. The ICAC found two reasons for the collapse. The first was that directors had engaged in a series of reckless loans for their own speculation or their own businesses. The second resulted from the activities of a criminal and his group that resulted in a cheque kiting scheme that generated as much as US$10 million a day. The bank did not take action to prevent a scandal but instead covered it up, using false loans to cover up the cheque kite losses. By the time of the collapse the loans and interest amounted to US$89.5 million.3

Another example of internal fraud involved the former directors of Ka Wah Bank and an investigation launched in 1986. A former director of the bank was involved in securing and cashing in on loans made out to business associates or employees of associated companies, who were often unaware of their involvement. Eventually, the former director was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.4

External fraud is also an issue, one that often affects bank customers who rely on the bank to provide a certain level of security. The issue is one that the HKMA is constantly working on. In June 2011, the HKMA issued a circular to individual AIs outlining the implementation details for chip-based technology in Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) and ATM cards. Between 2013 and 2015, cardholder protection should be significantly enhanced through a series of new security controls. By the end of February 2013, for example, AIs were expected to upgrade their ATMs to support chip-based authentication. In turn, they were also expected to replace all bank and credit cards linked to bank accounts by the end of March 2014 and by 2015 for the remaining cards. Some of these measures were outlined in a press release in October 2012. The HKMA noted at the time that ATM fraud is not a significant problem in Hong Kong but “it is important for Hong Kong to stay at the forefront of the technology and be in line with the international trend.” ATM cards with chips that work in conjunction with more traditional magnetic strips help prevent ATM fraud. At a more practical level, Hong Kong banks also set withdrawal limits outside Hong Kong to zero for all ATM cards, leaving it up to customers to reset those limits. The aim of these policies was to better manage the risk of external fraud associated with ATMs, which is the most common point of contact between customers and banking institutions.5

Issues associated with employment practices and workplace safety can also lead to operational risk loss events. These events are not necessarily unique to banks but may apply to all organisations that hire employees, particularly those who hire in large numbers. One issue that merits consideration for banks in Hong Kong is the disparity of employment laws between Hong Kong, which bases its laws and regulations on the English legal system and is famously flexible, and Mainland China, which has stricter rules that often favor employees and unions.

These risks are international, however. In September 2012, two law firms in the U.S. filed suit against Sterling Savings Bank for denying overtime pay to mortgage loan officers and other mortgage origination employees. The lawsuit involved both Sterling Savings Bank and Golf Savings Bank, which merged with Sterling in 2010. The lawsuit claimed employees were expected to work more than 40 hours per week without overtime pay. Still in the courts, the case illustrates not only the dangers of not tracking employment practices but also how banks may be found liable for issues that existed in entities that they acquire or merge with.

Operational risk events may also arise from business practices that have an impact on clients or operations. The case study outlined in Chapter 3 involving DBS Bank and the inadvertent destruction of safe deposit boxes is a case in point. Through distraction or neglect, bank staff and contractors allowed 83 safe deposit boxes still in use to be destroyed. The cost to the bank of that single incident was in the tens of millions of dollars.

Another example was the protracted dispute in Hong Kong over “Lehman mini-bonds,” structured investment products that many small investors bought ahead of the collapse of the investment firm from 16 different banks.6 Investors were warned of the dangers of the bonds in large prospectuses that few read. When Lehman Brothers collapsed at the launch of the global financial crisis, investors were left holding worthless bonds. A settlement reached in 2011 suggests investors got back between 85% and 96.5% of the value of the purchases, but only after years of protests outside of banks across the city. The outcome not only cost the banks that sold the products but also their reputations, regardless of any small print included in the contracts.

It is easy to understand how banks may face losses from natural disasters or other events. The World Trade Center bombing of 1993, outlined in Chapter 3, is a case in point. There are myriad other examples, including the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan or the floods in Thailand in October of the same year that stopped entire cities.

Similarly easy to understand, although not always easy to prevent, are events linked to system failures. The disruptions to the trading system of the Tokyo Stock Exchange (see Chapter 3) is an example but there are myriad others around the world. In an event that combined system failures with interanal fraud, in October 1998, German bank Westdeutsche Genossenschafts-Zentralbank (WGZ-Bank), lost US$200 million after two employees used computers to defraud the bank over 16 months. The employees used a loophole in the bank’s system that allowed them to enter false intermediary values and profit from trading in securities. The fraud was discovered when an updated system was installed following changes in national legislation.

In October 2012, the banking systems of Lloyd’s bank in the UK failed, hitting 22 million customers of Lloyds TSB, Halifax, and Bank of Scotland. The outage lasted an hour on a Friday afternoon. In June 2012, 12 million customers at Royal Bank of Scotland were hit by a computer failure that left many without access to cash for days when payments—including salary payments—were not credited.7

Issues of execution, delivery, or process can also lead to myriad losses from simple mistakes due to flawed credit or investment decisions. These are typically small losses but may be more frequent, so risk management frameworks have to account for them and find ways to minimise them.

Risk and Control Self-Assessment (RCSA)

Subjective assessment makes sense if historical data (either external or internal) are unavailable, expensive, of poor quality, or not readily applicable to a particular circumstance. Subjective assessment therefore is most appropriate for rare, high-impact, or catastrophic losses for which there are limited data.

Employees at banks and other financial institutions can evaluate their own risks and controls either individually or as a group, through workshops, focus groups, and self-assessment questionnaires, among other techniques. One advantage of risk control self-assessment (RCSA) is that line managers are experts in their business function. Therefore, they can provide the best details on risk and controls in their units, and can be more efficient than outside experts in reviewing new functions.

The downside to RCSA is that line managers may resist change or, worse, try to hide their own weaknesses and those of their unit. There is also a danger that a focus group or workshop degenerates into a “complaint” session.

The scorecard approach, although highly qualitative, is also useful. Line managers complete the scorecards at regular intervals, say annually, and these are reviewed by a central risk function. Scorecards may relate to risks unique to a specific business line or risks that cut across business lines. They may address inherent risks, as well as the controls to mitigate them. In addition, scorecards may be used by banks to allocate economic capital to business lines in relation to performance in managing and controlling various aspects of operational risk

Key Risk Indicators (KRI)

Operational risk managers use key risk indicators (KRIs) to determine how much risk is associated with a particular activity. KRIs are different from key performance indicators (KPI) in that the former are used to determine the possibility of an adverse impact while the latter helps measure how well something is doing. KRIs help determine how prone a particular organisation is to risk events, in this case operational risk. We have already considered some of these. They include the number of people in an organisation, the number of transactions it undertakes in a given period of time, capital-to-debt ratio, and others.

KRIs monitor the drivers of exposure associated with key risks. Both Basel and the HKMA guidelines provide some guidelines on KRIs banks should monitor.

It can also be useful to combine analysis of KRIs and analysis of KPIs to get some insight into operational weaknesses, which in turn can lead to operational failures and potential loss events. Banks and other authorized institutions can use escalation triggers as a self-warning mechanism, a gauge of risk levels that can keep operations within acceptable parameters and, if necessary, sound the alarms that ensure mitigation plans are put in place.

The HKMA says institutions should develop the right indicators to give management early warning of operational risk events as well as predictive information that can help risk managers identify potential sources of risk and act on those issues before they become problems.

Typical KRIs that banks track are selected from a range of indicators of operations and controls that are regularly tracked by various functions in a bank. The use of goals, limits, and escalation triggers on the appropriate KRIs can identify elevated levels of operational risk or a breakdown in operational risk management procedures before actual loss events occur.

ILD Building

Another important and useful tool to identify and assess operational risk is the collection and analysis of internal loss data (ILD). The BCBS suggests that this data “provides meaningful information for assessing a bank’s exposure to operational risk and the effectiveness of internal controls.”8

Basel II suggests banks map internal loss data into a series of business line and loss event categories, outlined in the June 2006 Basel II document. In this particular instance, the BCBS breaks down loss events and business lines into multiple categories, from the more general to the more specific. The BCBS recommends that banks, large banks in particular, map internal loss data to the first level of categories. A breakdown of these business lines is provided in the next chapter.

By analysing events that lead to losses, whether large or small, banking institutions can glean useful insights into the causes of losses that can prove to be ultimately large. A thorough ILD database can help banking institutions determine whether control failures are isolated or systemic. In so doing, banks may also determine and monitor the contributions to credit caused by operational risk along with market risk related losses. In so doing, an institution can get a full and complete picture of its operational risk exposure.

Managing Operational Risk

The 1988 Basel Accord established a single set of capital adequacy standards for international banks of participating countries from January 1993. Now known as Basel I that Capital Accord set minimum capital standards for banks to guard against credit risk. In April 1993, market risk was included in the scope of risks subject to capital charge requirements. The accord was amended in 1996 to fine-tune the approach to market risk.

In 1998 the Basel committee reached a new agreement, now known as Basel II, which extended, and in some parts supplanted, Basel I to reflect the financial developments of the intervening years, especially the diversity of risks faced by banks. One Basel II document titled Operational Risk Management explored the importance of operational risk as a financial risk factor. No discussion on requirement of a capital charge against operational risk was made until 2001.

The final version of Basel II was issued in June 2006, with some updates released in July 2009 and June 2011. Under these guidelines, operational risk was subjected to a regulatory capital charge. This regulatory capital—estimated separately by every bank—is designed to reflect the exposure of each individual bank to operational risk. The accord defines and sets detailed instructions on the capital assessment of operational risk and proposes several approaches for banks to estimate the operational capital charge. It also outlines managerial and disclosure requirements.

Exhibit 4.2 shows the basic structure of Basel II, which features three pillars. Pillar I, which addresses minimum risk-based capital requirements, focuses on credit risk, market risk and operational risk. Pillar II deals with the supervisory review process. Pillar III deals with disclosure of strategies and processes to deal with operational risk.

EXHIBIT 4.2 Structure of the Basel II capital accord

Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar. T Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi; Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2007), 38.

As the exhibit shows, Basel II allows several methods to measure the capital charge that banks should put aside in risk capital to cover operational risk: the basic indicator approach (BIA), standardised approach (SA) and advanced measurement approaches (AMA).

Risk Management Environment

The BCBS first put forth a framework of principles for operational risk management in February 2003, when it published Sound Practices for the Management and Supervision of Operational Risk. Three years later, the BCBS updated those principles in International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework—Comprehensive Version. This later document is the one that is generally known as Basel II. But, as the BCBS noted in 2011, Basel II was written with the understanding that both the industry and its practices would continue to evolve and that knowledge of operational risk would expand. This expectation, along with the knowledge gathered through loss data collection, quantitative impact studies, and a whole gamut of reviews of issues of governance, data, and modelling led to a number of changes to the 2003 document and the publication, eight years later, of Principles of Sound Management of Operational Risk and the Role of Supervision.

The thrust of the 2011 document is to incorporate evolved practices of operational risk management into a single document that covers governance, the risk management environment, and the role of disclosure, the three pillars included in Basel II.9

Principles of Operational Risk Management

Principles 6 and 7 fall under the second pillar. They deal with the identification and assessment of operational risk. These two principles put the onus on senior management of banks to first identify and assess operational risks present in a bank’s existing operations and to ensure that sufficient approval processes are in place for all new products that a bank may develop. The language of the principles is clear enough.

Principle 6 sets out the responsibilities of senior management in regards to existing risk. It says: “Senior management should ensure the identification and assessment of the operational risk inherent in all material products, activities, processes and systems to make sure the inherent risks and incentives are well understood.”10

Principle 7 extends this principle onto any new products that a bank may introduce, underlining the importance of continuous assessment and management of operational risk. Principle 7 states: “Senior management should ensure that there is an approval process for all new products, activities, processes and systems that fully assesses operational risk.”11

Monitoring and reporting are important because operational risk management is a continuous process of response to changes in operational exposures. Risk managers should learn to recognise any structural changes that could make existing models and loss data outdated. The nature and extent of the operational risks that face the bank may have changed since they were last assessed and may need to be updated.

The 2011 document seeks to incorporate the most updated and sophisticated approaches to operational risk management. The document considers the importance of monitoring and reporting in Principle 8, which notes: “Senior management should implement a process to regularly monitor operational risk profiles and material exposures to losses. Appropriate reporting mechanisms should be in place at the board, senior management, and business line levels that support proactive management of operational risk.”12

In general, the first phases of operational risk management are passive. They focus on identifying and defining risks, developing tools to measure risk and possible losses, and collecting data. It is in the later phases of the operational risk management process that more proactive steps begin to take shape. This second phase may include more refined analysis aimed at understanding the causes of operational risk and attempting to limit the risk and mitigate its impact.13

In very simple terms, Principle 9 as stated by the BCBS in June 2011 sets out the basic groundwork for this second phase of any operational risk management framework. At this state, the focus is still on Pillar II and the operational risk management environment that banks should create to follow Basel II. Principle 9 states: “Banks should have a strong control environment that utilizes policies, processes and systems; appropriate internal controls; and appropriate risk mitigation and/or transfer strategies.”

The HKMA, in its own Supervisory Policy Manual for Operational Risk Management, deals with risk control and mitigation at greater length. It makes it clear that banks and other AIs should have policies, processes, and procedures to control and mitigate operational risk as well as systems in place to comply with “documented” internal policies.14

Operational risk management methods should be more than just passive policies that remain static over time. Rather, these risk management policies should be developed in such a way that they can adapt to the growth of the bank, changes in business activities, or new developments in the market. This includes such emerging items as new products, new operations in branches and subsidiaries, or entry into new markets.

This last item can be particularly important for Hong Kong banks, most of which are either developing new operations in Mainland China or expanding their operations there. At the same time, this exposure creates new risks associated with a changing regulatory environment. Many of these risks would, by necessity, fall under the category of operational risk.

A strong internal control system is key because, when well designed and enforced it can help protect the resources of an institution and comply with existing rules and regulations. At the same time, says the HKMA, “sound internal controls will also reduce the possibility of significant human errors and irregularities in internal processes and systems, and will assist in their timely detection when they occur.”

Contingency plans are also important to limit losses or severe disruptions to a bank’s operations in the event of a significant loss event. The HKMA says management should review contingency plans periodically and ensure they remain consistent with a bank’s current operations and business strategies. At the same time, these plans should be tested from time to time to ensure that institutions can execute their plans “in the unlikely event of a severe business disruption.”15

The BCBS also addresses issues in Principle 10, outlined in the June 2011 document. This principle states: “Banks should have resiliency and continuity plans in place to ensure an ability to operate on an ongoing basis and limit losses in the event of severe business disruption.”16

The overall message of both Basel II and the HKMA’s policies is that operational risk management should be fully integrated into a bank’s operations. Banks should first consider the risks they face in every part of its operations, develop ways to track and measure risks, and have policies in place to control them while ensuring they also have contingency plans in place to both mitigate risks, limit escalation, and have the ability to continue operating should a large loss event come to pass.

Summary

- At its most basic level, operational risk management involves several activities that include identifying risk, measuring risk, preventing operational losses, mitigating the impact of a loss, predicting operational losses, transferring the risk to external parties, changing the form of the risk, and allocating capital to cover operational risk.

- Every bank and financial institution is ultimately different. For operational risk managers, this means that an effective process to control such risk requires input from multiple levels of management and from across different functions of the bank.

- Benchmarking risk requires three main steps. The first is to identify critical processes and resources with the help of multiple department heads and other management. The second is to describe critical process and resources with a checklist of questions that cover the importance of the process, the resources it utilizes, staff engaged, data available, and how it relates to other processes. The third step is to evaluate those processes and resources against a set of benchmarks that have been predetermined based on the strategic plan of the bank or institution.

- After benchmarking, the process of operational risk management moves on to identifying risk factors. This is often done through interviews with senior managers, managers, and line staff. In open-ended interviews, staff and management are asked about priorities and exposures, competitive trends, and other contextual information that helps frame the analysis of risk factors.

- There are two basic types of risk factors, external and internal. External risk factors are typically price-related and tend to have a direct impact on the revenue and assets of a firm. Internal risk factors tend to have indirect effects on profits and losses or asset values.

- Identifying loss events is the natural next step once risk factors have been identified. Potential loss events can be identified through brainstorming, and should be well defined and screened against.

- Loss events can be broken down into categories. Basel II includes the following categories of risk: Internal fraud, external fraud, employment practices and workplace safety, clients and products and business practices, damage to physical assets, business disruption and system failures, and execution and delivery and process management.

- The process of risk and control self-assessment (RCSA) is a subjective assessment based on the analysis done by staff ranging from line managers to experts in each business function.

- Key risk indicators (KRI) help determine how prone an organisation is to a particular risk event. KRIs help monitor the drivers of exposure to a particular risk, and can be used in combination with key performance indicators (KPIs) to develop insights into operational weaknesses that could turn into loss events.

- Internal loss data (ILD) is another useful tool to identify and assess operational risk. Basel II recommends banks map out ILD into a series of business line and loss event categories.

- The Basel II accord, first reached in 1998 and updated in 2006 and again in 2009, is based on three pillars: minimum capital requirements, supervisory review of capital and market discipline and public disclosure.

- Principles 6, 7, 8, and 9, outlined by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in 2006, lay out a basic framework for operational risk management. Principle 6 sets out responsibilities for senior management and Principle 7 extends this responsibility to new products. Principle 8 seeks to include the most updated approaches into the management of operational risk and Principle 9 focuses on the control environment.

Key Terms

Study Guide

Further Reading

Bank for International Settlements; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk; June 2011

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Basel II, Annex 9, pg. 105, www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.pdf

Cruz, Marcelo; Modeling, measuring and hedging operational risk; Singapore: John Wiley & Sons 2002

Hong Kong Monetary Authority; Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; November 2005; Section 8

Marshall, Christopher; Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001)

1 Marcelo Cruz; “Modeling, measuring and hedging operational risk”; Singapore: John Wiley & Sons 2002; Pg. 9.

2 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Basel II, Annex 9, pg. 105, www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.pdf.

3 http://www.kwok-manwai.com/Speeches/Corruption_Related_Fraud.html.

4 http://www.kwok-manwai.com/Speeches/Corruption_Related_Fraud.html.

5 http://www.hkab.org.hk/DisplayWhatsNewsAction.do?ss=1&id=1809.

6 “The good inside the bad”; The Economist” 31 March 2011.

7 Simon Read; “Lloyds banking systems failure hits 22m retail customers”; The Independent; 5 October 2012.

8 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk, June 2011, p. 11.

9 As identified in the June 2011 document Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk issued by the Bank for International Settlements.

10 Bank for International Settlements; “Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk”; June 2011; Pg. 6.

11 Ibid.

12 Bank for International Settlements; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk; June 2011; Pg. 6.

13 Marcelo G. Cruz; Modeling, Measuring and Hedging Operational Risk; New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. Pg. 11.

14 Hong Kong Monetary Authority; Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; November 2005; Pg. 24 – Section 7.4.

15 Hong Kong Monetary Authority; “Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management”; November 2005; Pg. 29 – Section 8.

16 Bank for International Settlements; “Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk”; June 2011; Pg. 6.