Chapter 1

Overview and Definition

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Understand how operational risk is defined by banking regulators, including the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), and under Basel II

2 Distinguish operational risk from other types of risk, including market risk and credit risk, and from operations risk

3 Describe how Basel I and II approached operational risk and its inclusion as a factor in determining capital adequacy

4 Define operational risk management and discuss its drivers, activities, and related disciplines

5 Understand the HKMA approach to operational risk

Introduction

Risk is an inherent part of the business of banking. It comes in various forms, each of which presents its own challenges to the proper functioning of a bank. One of the most all-encompassing of these risks is operational risk.

Operational risk in banks and other financial institutions did not become a focal point until the late 1990s and the work by the Bank for International Settlements’ Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) to define it, as well as develop frameworks to manage it and provide regulatory options. Through Basel I and the subsequent Basel II, operational risk moved from a position well behind the curtain to a role on the center stage of banking operations. Over the past decade, operational risk has taken on even greater importance. The BCBS principles on operational risk management were honed and streamlined.

This book seeks to define and explain operational risk, explore approaches to measure it, control it, and mitigate losses—in short, to explore operational risk management. It explores the sources of operational risk and the evolution of operational risk events. It seeks to offer readers and students the tools to determine bank exposures and develop strategies to mitigate it.

This first chapter lays the foundations for the rest of the book. It seeks to define operational risk, categorise it, and examine where it comes from. It outlines the approaches used in Basel II and by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA). The broad outlines of important operational risk events will also be considered before trying to differentiate operational risk from other types of risk, including operations risk, which is an entirely different category.

Lastly, this chapter considers the interplay between the risk management practices of various functions of a bank and operational risk, including financial risk management, audit and internal controls, and reliability engineering.

What is Operational Risk?

For banks and other financial institutions, risk is the inherent potential, while conducting business, for losses or fluctuations in future income that are triggered by events or ongoing trends. The usual forms of risk to which banks are exposed include market risk, credit risk, strategic risk, and operational risk.

Operational risk arises not only from a company’s operations, but also from any disturbance in its operational processes. The disruption may come from a one-off event, ranging from rogue trading to terrorist activities or a landmark legal settlement, or from a systems breakdown to sabotage, regulatory breaches, and even acts of God.

Because the triggers are so varied, it is difficult to come up with an exact definition of operational risk. The fuzziness of definition has led to two extreme categorisations. The “narrow” view sees operational risk as stemming from failure within a company’s back office or operations area. The “wide” view, on the other end of the spectrum, sees operational risk as a quantitative residual, that is, the variance in net earnings not explained by financial risks such as market risk and credit risk.

While simpler to understand, the “narrow” view is constraining because it does not take into account the many risks that can affect operations, for example, reputation or legal risks. The “wide” view, by contrast, is more encompassing, and separates risks that are relatively easy to measure from those that are not. The problem is that the wide view is too sweeping, and because it lacks specificity, is virtually impossible for use in managing operations.

Operational Risk in Financial Institutions

Most banking regulators adopt definitions that fall somewhere between these two views, focusing on the risk of failures in technology, controls, and staff. For example, the U.S. Federal Reserve Board’s Trading and Capital-Market Activities Manual defines operations and systems risk as “the risk of human error or fraud or the risk that systems will fail to adequately record, monitor, and account for transactions or positions.” The U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (1989) described operational risk as including system failure, system disruption, and system compromises.

For its part, the BCBS defines operational risk in its Basel II guidelines “as the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events. This definition includes legal risk, but excludes strategic and reputational risk.”

The HKMA closely follows the Basel II definition. In its Supervisory Policy Manual for Operational Risk Management, the HKMA defines operational risk as “risk of direct or indirect loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, staff and systems or from external events.”1

In evaluating operational risk, the HKMA requires authorised institutions (AIs) to take into account both product and AI-specific factors.

“The relevant product factors include the maturity of the product in the market, the need for significant fund movements, the impact of a breakdown in segregation of duties and the level of complexity and innovation in the market place,” it explains. “AI-specific factors, which can significantly increase or decrease the basic level of operational risk, include the quality of the audit function and programme, the volume of transactions in relation to systems development and capacity, the complexity of the processing environment and the level of manual intervention required to process transactions.”

Causal Factors

Determining the causes of operational risk is key to understanding and handling operational risk. In the last decade, understanding of operational risk has deepened considerably as has the ability of practitioners to separate operational risk from other types of risk such as credit risk, market risk, risks from interest rates or liquidity risk, reputational risk, legal risk, or strategic risk.

Operational risk has emerged as a much more significant issue over the last couple of decades as banks rely on more complex technology and automate their processes, develop more complex products, become larger through mergers and acquisitions, consolidate and reorganize their operations, outsource some functions, and adopt measures to control other types of risk that create new operational concerns.2

In setting out its approach to handle operations risk, the HKMA lays out four general causal factors for operational risk:

- Process factors;

- People factors;

- System factors;

- External factors.

Each of these, in turn, creates different categories of risk that are explored further in the next section.

Categories

The four main causal factors of operational risk—processes, people, systems, and external factors—all create manageable but potentially significant risks to an organization. Like the HKMA, the BCBS also suggests that identifying these four causal factors is the first step towards defining operational risk and then creating a framework to address it that is uniform across financial institutions. Each of these causal factors is relatively general in its scope and each can lead to significant risk events.3

Process Factors

The first causal factor, process risk, focuses on the internal structures that an institution uses to carry out its business. These processes can, and often do, carry significant risks with them.

There are multiple categories of risks that can be associated with process:

- Inadequate or inappropriate guidelines and procedures;

- Inadequate communication or a failure in communication;

- Erroneous data entry;

- Inadequate reconciliation;

- Poor customer or legal documentation;

- Inadequate security controls;

- Breach of regulatory and statutory provisions or requirements;

- Inadequate change management process; and

- Inadequate back up or contingency planning.

People Factors

People, whether intentionally or otherwise, can also pose a significant operational risk. Intensive training and careful, multi-layered supervision can help but there are still several categories of operational risk that stem from this ever-present causal factor. These include:

- Breaches of internal guidelines, policies, or procedures;

- Breaches of delegated authority;

- International criminal acts;

- Inadequate segregation of duties or lack of dual controls;

- Lack of experience;

- Staff oversight; and

- Unclear roles and responsibilities.

System Factors

In recent years, there have been a number of high-profile institutional failures—sometimes but not always related to financial institutions—that were caused by systemic risk. New computer software models that help stock traders do high-intensity trading with hundreds of thousands of trades per minute based on complicated algorithms have been highly profitable but have, at times, caused massive losses in just a few minutes. Banks and other financial institutions have lost customer data due to system failures and networks have been known to break down.

System risk may be easier to identify than other causal factors and there are fewer categories of operational risk associated with systems. Nevertheless, experience shows that this type of risk can be potentially devastating for a financial institution. The HKMA gives an example of a systemic risk factor in its guidance on Operational Risk Management issued as part of its Supervisory Policy Manual: Inadequate hardware, networks, or sever maintenance. It is probably safe to include inadequate software in this category as well.

External Factors

External factors can also pose significant operational risk to a banking institution. Here again, processes can be put in place to control or mitigate events associated with external risks, even if these are often harder to control. Among the categories of external risk are:

- Criminal acts;

- Vendor misperformance;

- Man-made disasters;

- Natural disasters; and

- Political, legislative, and regulatory causes.

Important Operational Risk Events

With broad operational risk causal factors broken down into somewhat narrower risk categories, the next step is to determine how categories translate into actual events and the potential losses that stem from those events. Operational risk management is fundamentally about managing risk to prevent operational losses, particularly large ones. The major operational risks are primarily driven by events such as fraud, sales practice violations, and unauthorised activities. The goal of operational risk management is to lower the frequency and severity of large-loss events.

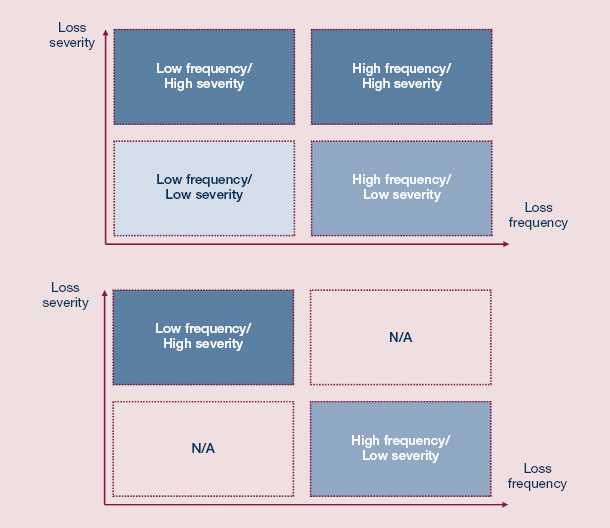

We can draw a four-section grid that depicts low frequency and high frequency loss events against small losses and large losses (see Exhibit 1.1).

EXHIBIT 1.1 Classification of operational risk by frequency and severity: unrealistic view (top) and realistic view (bottom)

Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007), 25.

The key challenge for operational risk management is to ensure a low frequency of major events that lead to large losses. Large losses from major events can destroy a bank. Perhaps the most famous example of such a destructive event is what happened at Barings Bank in the United Kingdom, which declared bankruptcy in 1995.

Barings was the oldest merchant bank in the UK, a venerable institution founded in 1762 that operated profitably for more than two centuries until one man with unchecked powers brought it all down. In 1993, Nick Leeson was appointed general manager of the Barings Futures subsidiary in Singapore. His job was to take advantage of low-risk arbitrage opportunities and leverage differences in price in similar equity derivatives on the Singapore Money Exchange (SIMEX) and exchange markets in Osaka, Japan. With little consideration for operational risk, Leeson was given control of both trading and back-office functions.

Leeson’s losses started to accumulate when the markets became much more volatile through 1993 and 1994 and he hid those losses in a special account (numbered 88888). The earth opened up under his (and the bank’s) feet when a massive earthquake struck Kobe on January 17, 1995. Leeson’s losses topped US$1 billion. His fraudulent practices did not become apparent until February, when he did not show up to work at his office in Singapore and tried to flee to England. In his own book, Rogue Trader, Leeson says he had built up an exposure in Japanese shares of more than GBP11 billion, which amounted to about 40% of the Singapore market. In March 1995, ING bought Barings for GBP1 and, before the year was out, Leeson was sentenced to six and a half years in a Singapore jail.4

All this could have been avoided through better internal controls and consideration of operational risks. What happened at Barings was monumental, a large loss, low frequency event that is not necessarily unique to the banking industry. Industries such as aviation, healthcare, chemical-processing, and railway also face similar dangers.

A secondary challenge for operational risk management is to stem the high frequency of small losses, although these usually are not a serious threat to the company. Often these minor losses can be incorporated into the cost of doing business (for example, credit-card fraud loss). Over time, operational risk management can spot the problem areas and find appropriate solutions to minimise or avert the occurrence of these minor but frequent losses.

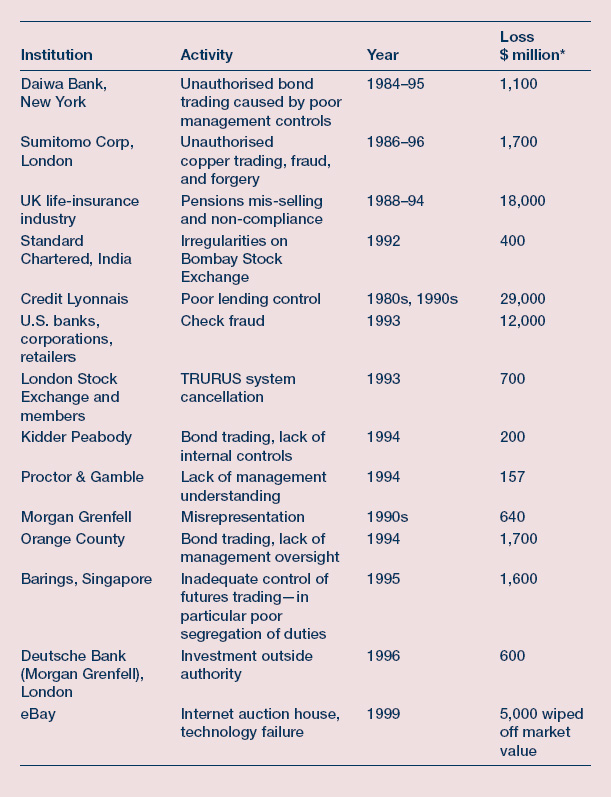

What happens when operational risk management fails? Exhibit 1.2 lists examples of highly severe but fortunately low-frequency events and operational shortcomings that resulted in big bank losses over two decades.

EXHIBIT 1.2 Examples of operational risks

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), 27.

∗ Approximate US$ cost as cited on at least one occasion in the press.

These events are not always associated with operational risk but they can be directly linked to failures in operational risk management.

Linked Events

An example of failures linked to operational risk can be found in hedge fund failures in recent years, failures that amount to about US$600 billion invested in some 6,000 funds.5 Hedge funds typically associate operational risk with the operating environment of the fund, including middle and back office functions, trade processing, accounting, administration, valuation, and reporting. It is a wide definition that makes it possible to link myriad events to operational risk management.

In Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions, Anna Chernobai, Svetlozar Rachev, and Frank Fabozzi quote a 2002 study by the Capital Markets Company (Capco) that linked about half of all hedge fund failures to operational risk. The most common failures include misrepresentation of fund investments, misappropriation of investor funds, often by investment managers, unauthorised trading, and inadequate resources. All these could feasibly be linked with operational risk.6

Legal Events

The definition of operational risk adopted by the HKMA (and by the BCBS) excludes strategic or reputational risk but includes legal risk. By defining operational risk as “the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and system or from external events,”7 the HKMA takes into consideration that accounting for legal events is a key function for operational risk managers.

New techniques to mitigate other types of risk such as those associated with collateralisation, credit derivatives, or asset securitization, may open the door for more legal risk that would fall under the broad umbrella of operational risk. These risks are included in the operational risk framework despite the fact that the HKMA’s risk-based supervisory approach suggests that AIs are subject to eight major types of risk: credit, market, interest rate, liquidity, operational, reputational, legal, and strategic. The old silo approach to managing risk is no longer seen as sufficient. Risks are often interlinked, as is the case with operational and legal risks. A bank may, for example, have operational processes to handle issues of security associated with mortgages or loans but if these processes lead to outcomes that do not conform with local laws or regulations then the process is intrinsically flawed and the resulting legal event may ultimately be the result of poor operational risk management.

At the same time, Hong Kong’s Banking Ordinance requires AIs to carry out their business with “integrity, prudence, competence and in a manner which is not detrimental to the interests of depositors or potential depositors.” In assessing a bank’s compliance with these requirements, the HKMA takes into account operational risk issues like the bank’s ability to deal with external shocks or unexpected contingencies, its ability to deal with fraud, the likelihood of operational errors, and the quality of systems and staff. At the same time, the Banking Ordinance calls for a capital adequacy ratio of 8% or more, which takes into account operational risk, credit risk, and market risk. Failures in any of these can lead to significant legal events.

There are other areas in which operational risk factors can result in legal events. For example, poor legal documentation can lead to risk events associated with process. Banks generate an enormous amount of paperwork and documentation. Inaccurate or inappropriate information in any of these documents can increase both legal risk and operational risk.8

The HKMA says banks should review all external documentation before issuing them. This includes considering the following:

- Compliance with regulatory and legal requirements;

- The use of standard and non-standard terms;

- Channels or ways in which documentation is issued; and

- Whether confirmation of acceptance is required.

Another important and potentially costly legal event is a change in the legal system of laws of a country or changes to a particular code, such as the tax code.9 The advent of a slew of new regulations to deal with the perceived failures of the financial industry in the past two decades (and particularly since 2008) have led to a series of such risks. At times, new laws and regulations have impact across borders. In the U.S. for example, the Bank Secrecy Act, the USA PATRIOT Act and anti-money laundering regulations all can generate risks for banks that operational risk managers should monitor carefully to avoid significant penalties and fines.

A case involving HSBC bank in 2012 highlights these risks. After a probe of several years, authorities in the U.S. linked the giant global bank to allegations of money laundering in connection to the bank’s acquisition in 2002 of Grupo Financiero Bital, a Mexican bank with a poor compliance system. U.S. authorities believe HSBC failed to improve procedures and that failure may have permitted some transactions to happen that exposed the bank to considerable legal risk. As of June 2012, the bank had set aside US$700 million for potential liabilities.10

Tax Events

Operational risk-related events that, in terms of the potential magnitude of associated losses, can be quite significant are associated with tax non-compliance or evasion, at times willful. These are events that the BCBS includes under its internal fraud category of loss events, alongside smuggling or check kiting.

Losses associated with tax non-compliance can be quite severe. Until about the 1990s, such events were rare and institutions typically had the ability to absorb the losses. As restrictions on the banking industry have been lifted, liabilities associated with tax events have risen. This is true for most operational risk events, the impact of which correlates to the size of an institution, its income, and the breadth of its business units. In the past 20 years or so, charges to banks have risen and changed their risk profiles.

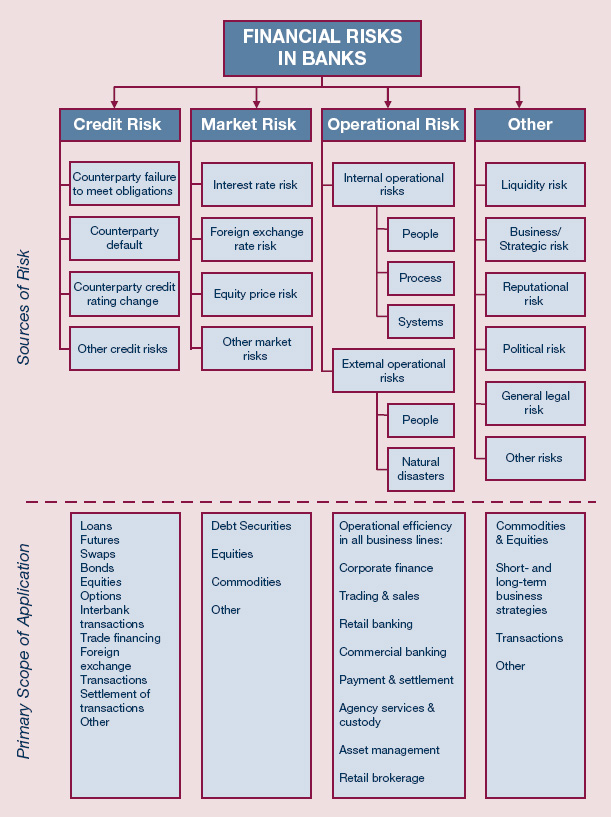

Distinguished From Other Risks

Until recently, the focus of banks had been on the credit risk and market risk of their business lines. Operational risk had not been viewed as seriously as either of these two risks because it is usually not taken directly in return for an expected reward. Nonetheless, operational risk exists in the natural course of banking activity, and in fact influences the entire risk management process. This is shown in Exhibit 1.3.

EXHIBIT 1.3 Topology of financial risks in banks

Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007), 27.

In setting out its approach to operational risk, the BCBS has set out three distinct pillars. Pillar 1, which considers the capital charge necessary to appropriately handle operational risk, aims to differentiate operational risk from other types of risk by focusing on key internal and external aspects of business operations that can lead to operational losses.11

Determining Risk Positions

In broad strokes, operational risk increases as institutions grow larger and more active. This is intuitive. The more people an institution has or the more transactions it carries out, the higher the chances that a mistake is made or a process is flawed. Larger banks are more likely to have larger operational losses.12

This suggests a number of indicators that help gauge the exposure of a particular institution to operational risk:

- Gross income;

- Volume of trades or deals;

- Assets under management;

- Transactions value;

- Number of employees;

- Experience of employees;

- Capital structure;

- Historical operational losses;

- Historical insurance claims for operational losses.

Operational risk exists in all business products, activities processes, and systems. This is an important reality because it means that a sound operational risk management framework has to cover all of them. It has to cover the entire portfolio of a bank.

Data Frequency

The generation and analysis of operational data is key to the development of a sound operational risk management plan. Banks should have procedures in place to produce timely and accurate reports not only during regular market conditions but also under unusual or extreme circumstances.

The BCBS supervisory manual says that reporting should be as frequent as needed to properly monitor and manage a particular risk. It is up to banks to improve their operational risk management reporting on a regular and ongoing basis to ensure that reports are “comprehensive, accurate, consistent and actionable across business lines and products.” More than that, the size and volume of reports should be conducive to their examinations. Thousands of pages of spreadsheets may offer a microscopic view of every bank operation but may ultimately prove useless if risk managers and bank management cannot decipher it.

A reporting system should take into account not only the type of risk, but also the speed and nature of the operating environment for that particular function. Market risk associated with a proprietary investment function is likely to be very different from that of a mortgage lending one. Just generating the reports is also not enough. Operational risk managers and directors should have access to these reports and review them regularly. At the same time, the result of ongoing monitoring efforts should be included in regular management reports and reports to the board of directors along with assessments of the current situation, changes to the operating environment, and assessments of the operational risk management framework done by internal audit functions and risk management functions. Whenever appropriate and necessary, all these reports should be circulated internally to senior management and the board.13

Modeling

Generating and monitoring data are key components of any operational risk management programme. The obvious challenge is what data to generate and how to present it. A practically useful and robust data model is key to any operational risk measurement and management system.

Analysts looking to build a strong data model for operational risk have to deal with a few key issues14:

- Direct and indirect losses: Direct losses have a direct bearing on results such as fees or penalties set by regulators or interests on a late settlement. Indirect losses, on the other hand, can arise from system crashes that result in failed transactions or a breakdown in a hedging strategy. The BCBS requires banks set aside capital for both direct and indirect losses.

- Causes and effects: It is easy to confuse cause and effect. “Human error” is typically a cause of operational risk rather than an effect. So, classifying risk by causes can lead to misunderstandings, particularly when there are a lot of loss events to consider. Take the example of risks associated with transaction processing and imagine that a system is poorly designed, leading to a large number of loss events from either human or system error. In this case, it is often difficult to tell either type of error apart. When developing a data model, it is important to avoid subjective classifications.

- Automated data feeds: Sometimes there are operational risks associated with collecting the data to model operational risk. Banks are often very large institutions and the data that goes into these models may come from thousands or tens of thousands of sources. It may come in different formats only to be gathered in a single location. Risk managers should ensure operational risk data is accurate and constant.

- Data warehousing: This is becoming easier as computer systems become more powerful. On the other hand, it is becoming more complicated as the amount of data that banks collect grows. The goal of setting up a data warehouse is to assist with compiling and analyzing data.

- Truncation, censoring, inflation: Data should be accurate but accurate data may also be wrong. Factors like inflation may play a role. At times, it is necessary to make corrections or some data required for a given set is missing (truncation). At times, specific values are missing from a data set (censoring). Data should also be corrected over time to allow for inflation, particularly when dealing with long-term financing or trading activities.

The evolution of our understanding of operational risk since it was first thoroughly considered in Basel I through to Basel II (and Basel III, which was still in development at time of writing) puts a lot of weight on accurate modeling. Studies on how to best collect loss data and quantitative impact have added to reviews of governance, available data, and modeling issues.

The 2011 document Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk underlines measurement as an important part of any operational risk management framework. Data models are used alongside audit findings, internal loss data, risk assessment, business process mapping, risk and performance indicators, scenario analysis, and comparative analysis to create a thorough risk management framework. The BCBS notes: “Larger banks may find it useful to quantify their exposure to operational risk by using the output of the risk assessment tools as inputs into a model that estimates operational risk exposure. The results of the models can be used in economic capital process and can be allocated to business lines to link risk and return.”15

Distinguished From Operations Risk

Operational risk is often mistaken for operations risk, but the two terms are not the same. The management of operations risk is a back-office task that involves processing and systems; it is primarily about managing the operations of a bank and its processing efficiency. Management of operational risk, on the other hand, has a much broader scope than just operations. As discussed earlier, operational risk manifests itself in all the activities of an organisation, including the head office, corporate functions, legal department, and board of directors.

Back Office Operations

Often out of sight to the general public, back office operations are an enormously important part of bank operations. Excluding interest costs, back office operations can account for as much as half of all operating costs for banks, according to McKinsey & Company.16 These back office operations handle mortgages and securities trading, process applications, and track the bank’s myriad activities. Banks are in a constant process of streamlining these operations to cuts costs. At times, they outsource some operations or combine various processes in different ways, from creating multiple process factories to a single massive operation. The approach varies depending on the size and experience of the bank.

By necessity, these activities generate exposure to operational risk that has to be carefully managed. McKinsey describes operational risk as a “financial institution’s exposure to losses arising from mistakes (such as computer failure and breach of regulations) and conspiracies (including loan fraud and embezzlement) that affect its day-to-day business”.17 This can be daunting in an atmosphere of constant change. In one case study, a fast-growing global bank put 300 new products on its back-office platform in a single year but it did not have standard approaches to deal with these operations, which meant midlevel traders often had to exercise much individual discretion.18 The result was enormous exposure with limited protection.

This is exactly the type of thing that Basel II guidelines seek to eliminate. The June 2006 document, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, by the BC, states that an effective internal process to assess compliance should include a critical look at back office operations “with a particular focus on qualifications, experience, staffing levels, and supporting systems.”19 It also notes that supervisory authorities should only approve internal models to manage risk that include sufficient skilled staff in “control, audit, and if necessary, back office areas”.20

Enterprise-wide Operational Issues

Operational risk can be found in almost every aspect of a banking operation. It can expose the bank to losses, large and small, at almost any level. Operational risks can be found in simple retail banking transactions that may open the bank to liability, reputational loss, and high frequency events that create small losses by themselves but can generate large losses when grouped together. They can also be found in large investment transactions through low-frequency large loss events that can cripple banks in a single, fell swoop, as can be seen through the cases outlined in Chapter 3. Operational risk should be clearly differentiated from the much narrower operations risk, which focuses on losses from errors and ineffective operations. Although banking and financial institutions have to deal with significant operations risk, its management is frequently relegated to the back office operations. From an enterprise-wide perspective, operations risk is a more focused concern.

Regulators have taken a wide view of operational risk management. In 2003, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) provided a definition that shows the type of broad view that operational risk managers need to take to be effective. The SEC defined operational risk as “the risk of loss due to the breakdown of controls within the firm including, but not limited to, unidentified limit excesses, unauthorised trading, fraud in trading or in back office functions, inexperienced personnel, and unstable and easily accessed computer systems.”

The HKMA’s own Supervisory Policy Manual for Operational Risk Management, also takes a broad view of the responsibilities of operational risk managers. The HKMA notes that AIs should notify the regulator when it makes changes that have a significant impact on operations. These events include21:

- Significant operational loss/exposure;

- Significant failures in systems or controls;

- Intentions to enter into an insourcing or outsourcing arrangement for banking related business, such as back office activities or changes to pre-existing arrangements;

- Changes in organization infrastructure or business operations; and

- Invocation of a business continuity plan.

In other words, while operations risk is certainly important it is easier to identify and track. Operational risk, by comparison, covers the breadth of an enterprise’s operations.22

Boundaries of Operational Risk

The HKMA differentiates operational risk from other risks as discussed below:

- Credit risk. The risk that the bank faces when it deals with a borrower or counterparty that may fail to fulfil an obligation. The assessment of credit risk involves evaluating both the probability of default by the counterparty, obligor or issuer and the exposure or financial impact on the authorised institution in the event of default.

- Market risk. The risk to a bank’s financial condition emanating from adverse movements in market rates or prices such as foreign exchange rates, and commodity or equity prices. The main determinant of the inherent market risk in a business line is the volatility of the relevant markets. In assessing inherent market risk, the AI should consider the interaction between market volatility and business strategy. A trading strategy that focuses exclusively on intermediation between end-users will tend to result in less market risk than a purely proprietary strategy.

- Interest rate risk. The risk to an AI’s financial condition emanating from adverse movements in interest rates. To determine the levels of interest rate risk, the bank should assess repricing risk, basis risk, options risk, and yield curve risk. The AI must also evaluate its funding strategy with respect to interest rate movements and the impact of the overall business strategy on interest rate risk.

- Liquidity risk. The risk that an AI may be unable to meet its obligations as they fall due. This may be caused by “funding liquidity risk,” that is, the AI’s inability to liquidate assets or to obtain funding to meet its obligations. The problem could also be caused by “market liquidity risk,” where the bank is unable to easily unwind or offset specific exposures without lowering market prices significantly because of inadequate market depth or market disruptions.

- Reputation risk. The risk that negative publicity regarding a bank’s business practices, whether true or not, will lead to a deterioration in the size of the customer base, litigation, or a fall in revenue. Market rumours and public perceptions are significant factors in reputation risk.

- Legal risk. The risk arising from the possibility that unenforceable contracts, lawsuits, or adverse court judgments may disrupt or otherwise negatively affect the operations or financial condition of an authorised institution.

- Strategic risk. The risk of negative impact, both current and prospective, on a bank’s earnings, capital, reputation, or standing because of poor business decisions, improper execution of decisions, or lack of response to industry, economic, or technological changes. This risk is influenced by a mismatch in an organisation’s strategic goals, the business strategies developed to reach these goals, the resources to meet these goals, and the quality of execution.

Basel II has elevated operational risk to the same level as market risk and credit risk. The capital charge that banks must set aside and count as part of the computation of their capital adequacy takes all three risks into account.

Drivers of Operational Risk Management

There are many reasons why operational risk management is an important part of risk management and the proper functioning of banks. Some of the salient factors include:

- Culture. Both BCBS and the HKMA suggest that banks should breed the right risk culture through their ranks, not just among risk managers, but across an entire organization. Effective operational risk management includes ensuring that a bank or other institution has the right risk culture and can help mitigate risk, make risk identification faster and more effective, and encourage staff to come forward with potential risks that may have been missed or ignored. An unsound risk culture could make risk management and control more difficult.

- Strategy, appetite, and policy. Risk management should fit within a bank’s strategy, appetite, or willingness to take on risks and the risk control policies set by the board. The operational risk management framework of a bank is key to fine tuning a bank’s operations to match these three factors. Through careful implementation of its operational risk management framework a bank can prevent unsound strategies from being adopted at various divisions, or operations that exceed the management’s willingness to take on risk or that break the policies set by the board of directors.

- Pressure from regulators. Regulators are requiring banks and other financial institutions to set aside increasing amounts of capital for operational risk. Having an operational risk management programme can help a bank to quantify such risk. Operational risk managers can work with regulators to ensure compliance and to reassure them about the bank’s risk management, thereby helping to free up capital.

- Increasing merger and acquisition activity. Both friendly and hostile, this has propelled industry-wide consolidation and led to a multitude of operational risks triggered by the need for post-merger integration.

- Integration of best risk practices. Operational risk managers can lead the integration of best risk practices over a wide range of a bank’s functions such as compliance, insurance, risk management, operations, and facilities management. Management responses to common risks can therefore be uniform rather than ad hoc and particular to a function or business unit.

- Risk aggregation. Risk can be aggregated across several business lines for a bird’s-eye view of the bank’s risks. This helps to identify natural hedges and to direct management attention to exposures across the bank, rather than the execution of expensive piecemeal risk management through locally developed control systems.

- New products and services. New product and service proposals can be examined for any hidden risks (say, of liquidity or credit exposure) that senior management, and front-office sales, marketing, and trading staff may not fully understand. Operational risk management teams should also lead the development of management and control solutions/policies to minimise risk.

- Measuring performance and resources. Performance and resource allocation measurement assumes measures that incorporate all the risks associated with a particular business or activity. Measures of operational risk can help to avoid problems of moral hazard whereby the risks are passed from one business area to another.

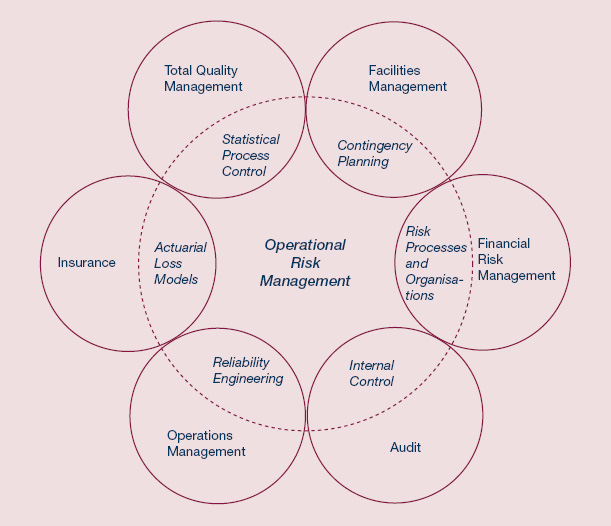

Integrating Related Disciplines

In conducting operational risk management, the techniques of other disciplines are helpful, as shown in Exhibit 1.4. The relevant outcomes of these other business processes are also integrated in operational risk management.

EXHIBIT 1.4 Operational risk management and related disciplines

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), 30.

Financial Risk Management

Clear risk processes and organisational structures have been set up to measure, analyse, and manage financial risks within businesses. This is because financial assets have well-defined mark-to-market values, and financial institutions can estimate the risks of these assets. Moreover, financial instruments such as swaps, options, and futures are readily available to offset these risks.

The trend towards quantifying market and credit risks has naturally led to applying similar techniques to operational risk management. Specific tools such as stress testing and value at risk have been used in this task. The most important has been the adoption of an integrated set of risk processes and an organisational structure to handle operational risk.

However, most financial modelling techniques are not easily transferable to managing operational risk because of lack of reliable data, uniqueness of exposures to particular firms, and the absence of hedging vehicles.

Audit and Internal Controls

Accounting control systems are designed to ensure that a business operates in line with strategies developed by senior management. Diagnostic controls, as well as a series of limits and sanctions, help ensure that operations are conducted as they should. Internal and external audits focus on confirming the existence of assets and liabilities for which the firm is responsible and accountable. To do this, auditors traditionally use a series of interviews and checklists to confirm operational integrity.

Operational risk management uses similar qualitative tools, but goes beyond these to quantify risks, and thereby allocate resources.

Reliability Engineering

Reliability engineering is a body of statistical and analytical techniques concerned with the reliability, safety, and efficient operation of engineering systems. Reliability engineering focuses on systems maintenance and reducing operational uncertainty by setting and meeting realistic operating specifications for process output.

Operational risk management has derived techniques from reliability engineering to use in safety-sensitive fields such as nuclear plant safety, aircraft maintenance and medical informatics. Moreover, the systematic gathering, categorising, analysing, and prioritising of data used in the engineering disciplines help to develop rigorous operational risk management methodology.

There are certain clear differences between engineering and operational risk management. Reliability engineering approaches tend to be very data-intensive and to focus on the evolving reliability of complex multi-component hardware systems. By contrast, the organisational systems that comprise ongoing operations are data-poor and involve people. This makes gathering data and predicting the systems’ failure patterns much more challenging than that for hardware systems.

Another difference is focus. Engineers concentrate on reliability (the likelihood of a system functioning correctly), while operational risk managers focus on the financial impact of down-time and estimate potential costs of the next period.

Summary

- Until recently, operational risk has not been viewed as seriously as market or credit risk because it is not regarded as directly yielding an expected reward. But this type of risk exists in the natural course of banking activity, and influences the entire risk management process. Basel II has elevated operational risk to the level of market and credit risk by requiring banks to set aside a regulatory capital charge to reflect their exposure to operational risk.

- The HKMA defines operational risk as “the risk of direct or indirect loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, staff and systems or from external events.” Under Basel II, operational risk is defined as “the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events.” The source of operational risk is not only a company’s operations, but also any disruption in the operational processes, including one-off events such as rogue trading, terrorist activity, sabotage, and acts of God.

- Like market and credit risks, operational risk can be quantified by loss distribution, and loss severity and frequency. To mitigate operational risk, a bank needs internal controls and adequate insurance coverage. Basel II details instructions on the capital assessment of operational risk and proposes ways for a bank to estimate the capital charge.

- The conduct of operational risk management involves several activities, including identifying the risk, measuring the risk, preventing operational losses, mitigating the impact of a loss, predicting operational losses, transferring the risk to external parties, changing the form of the risk, and allocating capital to cover operational risks. The techniques and outcomes of other business processes are helpful. These related disciplines include financial risk management, audit and internal controls, insurance, and total quality management.

- The HKMA has adopted a risk-based supervisory approach that emphasises effective planning and examiner judgement. Examinations are customised to suit the size and activities of AIs and to focus examiner resources on areas that expose the AI being examined to the greatest degree of risk.

Key Terms

Study Guide

Further Reading

Abkowitz, Mark D. Operational Risk Management: A Case Study Approach to Effective Planning and Response. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2008. Print.

Bank for International Settlements. International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework, Comprehensive Version, June 2006. Web. 19 July 2010. http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.pdf?noframes=1

Chernobai, Anna S., Rachev, Svetlozar T., Fabozzi, Frank J. Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2007. Print.

Choudhry, Moorad. Bank Asset and Liability Management: Strategy, Trading, Analysis. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2007. Print

Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Risk Based Supervisory Approach in Supervisory Policy Manual. Web. 19 July May 2010. <http://www.info.gov.hk/hkma/eng/bank/spma/attach/SA-1.pdf>

Marshall, Christopher. Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2001. Print.

Taylor III, Bernard W. and Russell, Roberta S. Operations Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2009. Print.

1 HKMA Supervisory Policy Manual, Risk-based Supervisory Approach (HKMA, 11 October 2001), 20.

2 HKMA Supervisory Policy Manual, Risk-based Supervisory Approach (HKMA, 11 October 2001), 20.

3 HKMA Supervisory Policy Manual, Risk-based Supervisory Approach (HKMA, 11 October 2001), 20.

4 Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007).

5 Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007).

6 Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007).

7 Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; 28 November 2005. Pg. 3.

8 Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; 28 November 2005. Pg. 28.

9 Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007).

10 Shahien Nasiripour, Caroline Binham, Patrick Jenkins; HSBC faces probe on money laundering claims; Financial Times; online; 15 July 2012.

11 Dowd, Victor; “Measurement of operational risk: the Basel approach.” Operational Risk: Regulation, Analysis and Management. Ed. Carol Alexander. Great Britain: Prentice Hall, 2003. P. 36.

12 Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007), Ch. 2.

13 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk, June 2011, p. 13.

14 Marcelo G. Cruz; Modeling, Measuring and Hedging Operational Risk; New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2002. Pg. 11.

15 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk, June 2011, p. 12. The reference to modeling is part of Principle 6 of the BCBS’ approach to operational risk management, which focuses on identification and assessment of risk and puts the onus on senior management to ensure operational risk is identified and assessed in all “material products, activities, processes and systems.”

16 Driek Desmet, David Fine and Jacques Meyer; “Banking behind the scenes”; McKinsey Quarterly; December 2002; accessed online at www.mckinseyquarterly.com on 3 October 2012.

17 Robert S. Dunnett, Cindy B. Levy, and Antonio P. Simoes; Managing Operational Risk in Banking; McKinsey Quarterly; February 2005; accessed online at www.mckinseyquarterly.com on 3 October 2012.

18 Cindy B. Levy, Hamid Samandari and Antonio P. Simoes; “Better operational-risk management for banks”; McKinsey Quarterly; August 2006; accessed online at www.mckinseyquarterly.com on 3 October 2012.

19 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards”; June 2006; Pg 109.

20 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards”; June 2006; Pg 191.

21 Hong Kong Monetary Authority; Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; November 2005; Pg 8 – Paragraph 2.2.3.

22 Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007), Ch. 2.