Chapter 5

Risk Identification

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Understand what a risk self-assessment (RSA) and a risk and control self-assessment (RCSA) are and how they help banks manage operational risk

2 Outline ways in which risk factors can be categorised, such as by location of impact, source of risk, control responsibility, cost account, and convention and place these categories within the Basel II risk matrix

3 Explain why business line mapping is important for banks and outline the eight general business lines that the BCBS recommends mapping

Introduction

Controlling operational risk requires, as we discussed earlier, both identifying it and measuring it. This is not always straightforward but more than a decade of exploration and greater awareness of operational risk have made it possible to develop a comprehensive tool kit for the management and control of operational risk. But where does operational risk fit within the grand scheme of a bank’s operations? More to the point, where do specific loss events fit in within the process of managing operational risk?

As we discussed in the previous chapter, banks typically analyse and identify the operational risk factors they face using a number of methods, including a risk and control self-assessment (RCSA), which is a thorough look at the current status of operations and the exposures in segment based on careful consideration of such elements as key risk indicators (KRIs) and the mapping of internal loss data (ILD), which can then be compared against external loss data to determine operational risk exposure.

In order to manage these risks factors, however, they have to fit within a framework of operational risk management. And in order to develop a framework the operational risks that are identified through various assessments and analysis have to be categorised. Rigorous and uniform categorisation of risk produces a clearer picture of a bank’s operational risks. The BCBS has provided a ready-made approach for the categorisation of risk with a risk matrix that correlates seven different loss events with eight different business lines. All in all, the matrix provides for 56 different operational risks. Taxonomy is important. An inconsistent taxonomy makes it more likely that risks will be ignored, not identified, or not assigned to any specific function and, thus, overlooked. The process of identifying risk, categorising risk, and compiling ILD is likely to generate a large quantify of data that can be compared with yet another piece of the puzzle, external loss data (ELD).

There are multiple ways to categorise risk. Risks can be categorised by location of impact, by the source of the risk, by control responsibility, by cost account, or by convention. All these categories are described in this chapter. Accurate mapping of business lines is also necessary to more effectively identify risks. Potential risk exposures can be combined with business line maps into an operational risk matrix that can easily identify risks.

One large obstacle to developing useful and detailed models of operational risk is a lack of data. By the time the BCBS updated Basel II in 2006, there was less than half a decade of data available. By 2011, available data spanned a decade or more, which made it possible to develop more detailed and useful models. Nevertheless, available data on operational risk was much less than the data available for other types of risk such as market risk.

One way around this problem was to pool internal and external data so that banks could populate operational risk databases more thoroughly. There are two reasons for this. The first is to expand operational risk databases to increase the accuracy of statistical estimations. The second is to develop models that can account for losses that have not occurred within a bank but are not unlikely.1

Even with the existing data, banks should put in place methods to determine and control risk, the first step of which should be internal self-assessments. These self-assessments should be based on careful categorisation of operational risk.

Assessing Risk

There are multiple ways to assess risks to a bank’s operations. Even if a bank or other AI has controls already in place to deal with risk it is important to regularly self-assess both risks and the controls in place. We will discuss in the next chapter three methods to assess the actual impact, in real terms, of the operational risks that are identified through the various methods discussed here and in previous chapters. These methods to measure impact include historical analysis, subjective risk assessments, and implied risk estimation using models.

Banks take different approaches to determine the risk they face but they all, typically, engage in a couple of assessment processes before moving on to more detailed categorising of risk and analysing their likely impact on operations. Through a risk self-assessment (RSA) process, banks assess the processes that lay underneath their operation and balance them against possible threats and vulnerabilities to consider their potential impact on the bank. In other words, through an RSA process, the bank looks for weaknesses in its operations and tries to estimate how those weaknesses can lead to losses and how large or small those losses would be.

A risk and control self-assessment (RCSA) process extends this further by evaluating “inherent risk.” Inherent risk is defined as the risk of a particular event before controls are taken into consideration. The RCSA process also looks at the control environment and the residual risk or the risk that remains after controls are considered. Not only are RCSAs an important element of an operational risk management framework, but it is also necessary to do them on an ongoing basis and to report the findings of these assessments to management.

The BCBS says banks should include the results of its RCSA into its overall business strategy and development process because “risk identification and assessment are fundamental characteristics of an effective operational risk management system.”2

For its part, the HKMA is adamant not only on the importance of RCSAs but also on the ongoing reporting of findings to management. These reports are important for without them, the process can be useless. The information included in such reports should be carefully considered; too much information on the wrong details can be as counterproductive as too little information on important risks. The Hong Kong regulators say reports should include a range of relevant data, including financial, operational, and compliance data along with external market information on current events and conditions that are important to making operational decisions. According to the HKMA, these reports should include information such as3:

- Critical operational risks facing or potentially facing the institution based on KRIs as well as changes to RCSA, comments from audit and compliance review reports, and others;

- Major risk events and losses, issues identified and intended remedial actions;

- Status and effectiveness of actions taken; and

- Reporting of exceptions.

Using the RCSA process, a bank can develop scorecards by weighing residual risks and develop a way to translate the results of this exercise into metrics that can rank the current controls in terms of their effectiveness at mitigating risk. Larger banks can also use the results of the risk assessment to develop models that estimate their exposure to operational risk.

Comparing the frequency and severity of internal data against the RCSA can help banks determine whether processes in place are effective. An even better understanding can be developed by comparing this data with internal and external data.4

Risk and Control Self-Assessment

For more than a decade and a half, banks and finance companies serious about managing their operational risk have undertaken a series of inward looking exercises to identify risk exposures. One common such exercise is the RCSA, which banks have been doing regularly since the 1990s. Most regulators around the world have encouraged banks to use RCSA for more than two decades.

RCSA is a very subjective exercise that involves gathering information, often from frontline staff, about bank operations, awareness of risk, and approaches to managing risk. Most often, this information gathering is done in the form of questionnaires. Risk managers then assess and analyse the information gathered in these questionnaires to determine how it impacts the operational risk framework of a particular bank.

A complex banking operation might feasibly produce hundreds of these questionnaires on a regular basis. For example, branch tellers might have to answer questions on their awareness of whether they are exposed to a particular risk, such as money laundering. Depending on the answer, yes or no, the questionnaire might then lead the staff member to explain how they are exposed to that particular risk, what measures are in place to tackle it, and more. Every job in a bank, every position, would have a different RCSA questionnaire. Equity traders, for example, face different risk exposures than front line staff at a branch. Their questionnaires might focus on the legality of transactions, their awareness and application of trading limits, and so on.

As a source of information, an RCSA can be incredibly valuable but it can also be close to useless. As one expert explains, the principle of “garbage in, garbage out” applies. If the questions in the RCSA are badly designed or do not elicit the necessary information, the output of the RCSA will be of little value. Since the 1990s, the understanding of what to ask and how to ask it has evolved considerably. Yes or no answers are often not very useful. Rather, an RCSA questionnaire should elicit discussion, and encourage staff to identify problems or gaps in the operational risk controls and possible solutions.

One approach that has emerged in recent years has been the use of workshops to carry out the RCSA process. By answering questions in groups, individuals may be encouraged to be more forthcoming with problems and issues while gaining greater awareness of risk exposures and control. The benefit of using the workshop approach is immediately obvious. People in similar positions might have different views of exposure. Two tellers from the same branch might have entirely different answers to the question of whether they are exposed to money laundering risks. If one answers “no” and another “yes” in a group setting, the difference of opinion might elicit a discussion that is both useful to identify exposures while generating greater awareness among staff.

The use of experts as referees is also useful, as they can help create greater awareness among staff. A simple questionnaire that an individual might answer in minutes without much thought is unlikely to create any great benefits for anyone beyond generating some moderately useful input. On the other hand, if a group of staff spend three or four hours in a group discussion that results in well-considered answers, the end result might not only be useful information but also might be educational for the staff who might not usually spend a lot of time thinking about operational risk.

Take internal fraud as another example. Ten different staff might walk into a workshop with a very different understanding of what internal fraud means in the context of the bank. By the time they walk out, however, they might have greater awareness and insight. For the bank, the RCSA might have a double benefit. It not only helps management identify risks but it is also a training opportunity. An even more effective way of creating this awareness is to invite participants who successfully complete a workshop to come back as group leaders for a similar exercise in the future.

There are some challenges in implementing RCSAs, both individually or in groups. The biggest such issue is that people are naturally prone to hide risks, or report less risk than they are actually exposed to, either to protect their jobs or to avoid the increased paperwork that might come from a bank deciding that a particular business activity is riskier than it actually thought. Most often, there is nothing nefarious about this tendency of staff to hide or underreport risk. It is, nevertheless, something that all banks should take into account. The workshop approach to RCSA is one effective way to deal with this tendency to hide or underreport risk.

Categorising Risk

Operational risk analysis is based on comparing risks across various meaningful categories. The more rigorous and uniform the categorisation, the more slicing and dicing can be done to get a clearer and more granular picture of the bank’s operational risks.

Category Types

Events and risk factors can be categorised in several different ways. At times, banks will undertake multiple categorisation exercises to cross-check risks. The ways in which operational risks can be categorised include location, where the impact of the event or factor is realised (business unit, process, function, resource, geography, market, product, customer); the source of the event or factor; control responsibility, where the impact of the event or factor is controlled; the resources used to manage the risk (insurance, hedging); and industry or regulatory conventions. Details of each of these types of categories are outlined below:

- By location of impact. This describes which businesses or processes bear the impact of an event or risk factor. The same event often affects multiple processes and resources. Often this is why no one business unit takes responsibility for an event and consequently no action is taken.

- By the source of the risk. There is a distinction between the owner of the risk (where the risk is either initiated or managed) and its impact. For example, marketing and sales may be responsible for developing and selling a complex product, but the resultant operational risks are realised in the operations group. It is there that additional staff specialists will be needed to process the documentation and legal risks associated with the product.

- By control responsibility. Events or risk factors, if controllable, are always controllable by a company function or combination of functions. Sometimes the unit able to control a factor or loss event is also the area affected. More often, control is shared between the upstream authorised source of the risk and the unit responsible for managing that risk. For example, a trader initiates a risk by proprietary trading; the back and middle offices manage the risk through limits, reconciliation, and control.

Control denotes the business area’s ability to prevent or mitigate the loss associated with the specific event. In the case of employee fraud, for example, the control might be shared between the human resources department, which hired the employee, and the internal controls area, whose procedures and systems failed to anticipate the fraud. The closer the loss event is to the originating cause, the more viable loss prevention activities become compared with loss mitigation. Categorisation by risk control responsibility is necessary for risk-transfer pricing within the company. The locus of control, rather than where the events are realised, should determine internal risk-transfer and risk-based resource allocation.

Because risks may be borne by units other than those controlling the risk, moral hazard can be a major problem, whereby the risk controller does not bear the costs associated with the risk and therefore fails to take appropriate controlling action. If it is known which events connect to the specific processes and resources that control them, it can be known which areas are responsible for the events. Even for an uncontrollable event for which no business area holds direct control, the event can be allocated to a group responsible for risk financing, such as financial risk management or insurance management.

- By cost account. Expenses and write-offs will often be posted to a loss account within the general ledger. This reflects accounting conventions rather than economic reality, but may still be useful in developing a pro forma estimate of cost items in the income statement. It is also appropriate for use with expense-based models.

- By convention. Risk categorisation may also reflect regulatory or internal conventions. Despite the many differences reflecting their different agendas, risk categorisations share a structure as illustrated in Exhibit 5.1.

EXHIBIT 5.1 A typology of operational risks

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), 180.

| Business event risks | Shift in credit rating | |

| Reputation risk | ||

| Taxation risk | ||

| Legal risk | ||

| Disaster risk | Natural disaster | |

| War | ||

| Collapse of markets | ||

| Regulatory risk | Capital requirement breach Regulatory changes | |

| Operations risks | HR risk | Employee turnover |

| Key personnel risk | ||

| Fraud risk | ||

| Error | ||

| Rogue trading | ||

| Money laundering | ||

| Confidentiality breach | ||

| Technology risk | Programming error | |

| Model risk | ||

| Mark-to-market error | ||

| Management information | ||

| IT systems outage | ||

| Telecommunications failure | ||

| Contingency planning | ||

| Relationship risk | Contractual disagreement | |

| Dissatisfaction | ||

| Default | ||

| Facilities risk | Safety | |

| Security | ||

| Operating costs | ||

| Fire/flood | ||

| Transaction risk | Execution error | |

| Product complexity | ||

| Booking error | ||

| Settlement error | ||

| Commodity delivery risk |

Business Line Mapping

For larger banks, the BCBS recommends mapping ILD particularly as they relate to top-level business lines5 that include somewhat general lines before breaking them up. These general lines are:

- Corporate finance: Includes corporate finance, municipal and government finance, merchant banking and advisory services, and such activities as mergers and acquisitions, underwriting, privatisations, securitisation, research, debt, equity, syndications, IPO, and secondary private placements.

- Trading and sales: Further broken down into sales, market making, proprietary positions, and treasury, and such activities as fixed income, equity, foreign exchanges, commodities, credit funding, own position securities, lending and repos, brokerage debt, and prime brokerage.

- Retail banking: Retail and private banking as well as card services are included in this category with such activities as retail and private lending and deposits, banking services, trust and estates, investment advice, various cards, private labels, and retail.

- Commercial banking: Includes activities such as project finance, real estate, export finance, trade finance, factoring, leasing, lending, guarantees, and bills of exchange.

- Payment and settlement: Further broken down among external clients, it includes payments and collections, funds transfers, clearing, and settlements.

- Agency services: This business line is broken down into custody, corporate agency, and corporate trust and such activities as escrow, depository receipts, securities lending (customers), and corporate action as well as issuer and paying agents.

- Asset management: Includes discretionary fund management and non-discretionary fund management and activities like pooled, segregated, retail, institutional, closed, and open fund management and private equity.

- Retail brokerage: Covers the execution and full service of retail brokerage business.

These upper-level business lines can be further broken down into more specific areas. For example, corporate finance can be further broken down into corporate finance, municipal or government finance, merchant banking, and advisory services. In turn, this second level of business line can be further categorised into mergers and acquisitions, underwriting, privatizations, securitisation, research, debt, and more.

Mapping ILD to the top business line can be helpful to compare internal loss data with external loss data and set out a better picture of operational risk exposure.

There are a number of hurdles that can impact how effective a map of operational risk can be. One such issue is the taxonomy associated with operational risk management. The BCBS considers this issue. An inconsistent taxonomy—referring to how risk is categorised—across different functions of a bank increases the likelihood that operational risks are not identified or categorised. This, in turn, increases the likelihood that responsibility for assessing, monitoring, controlling, and mitigating a particular risk is not clearly defined, which could lead to a higher incidence of a particular risk event.

The BCBS is adamant that an operational risk management framework should allow for an institution-wide taxonomy for operational risk terms “to ensure consistency of risk identification, exposure rating and risk management objectives.”6

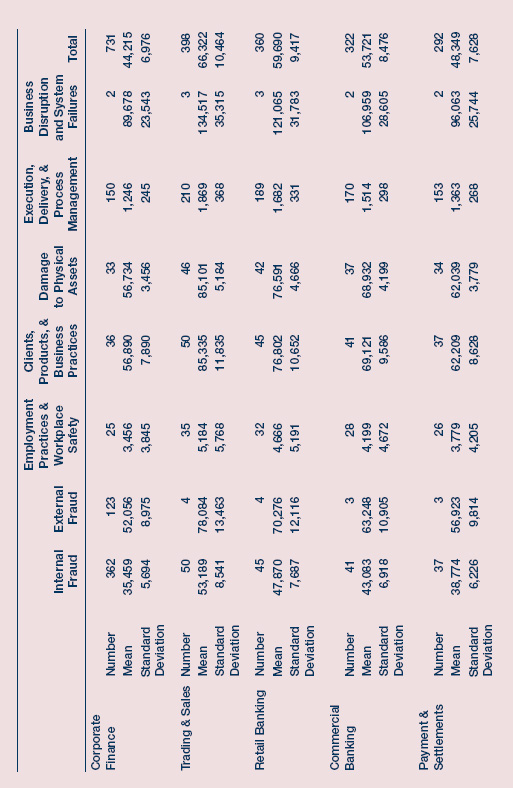

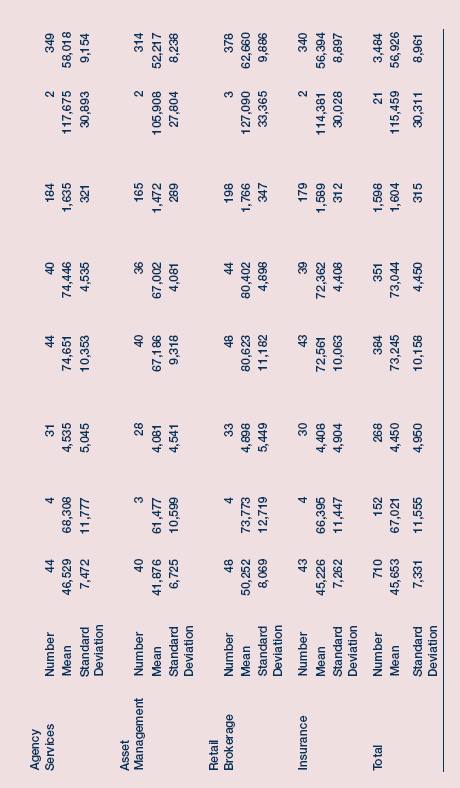

The BCBS has developed an operational risk matrix that correlates seven loss events against eight business lines, creating 56 cells, each of which represents a potential operational risk for banks and financial institutions. Exhibit 5.2 shows an example of one such operational risk matrix. Note that this is a hypothetical illustration. In practice, not all the cells will probably have enough loss data and other information to be quantified and filled in.

EXHIBIT 5.2 Hypothetical example of an operational risk matrix

Source: HKIB

The main business risks included in the BCBS matrix are:

- Internal fraud;

- External fraud;

- Employment practices and workplace safety;

- Clients, products, and business practices;

- Damage to physical assets;

- Execution, delivery, and process management; and

- Business disruption and system failures.

Summary

- The gathering of internal loss data (ILD) is necessary to determine risks and mitigate their effects. Given the relatively short history of the operational risk management function in most banks and other financial institutions around the world, ILD can be supplemented with external loss data (ELD) to create a more detailed picture of the potential impact of operational risk factors and events.

- A risk self-assessment (RSA) helps banks assess processes that lie below their operations and balance them against threats and vulnerabilities.

- A risk and control self-assessment (RCSA) takes the RSA process further by evaluating inherent risk, which is defined as the risk of a particular event before controls are taken into consideration. The RCSA also takes into account the risk that remains after controls are taken into consideration.

- The RCSA often takes the form of questionnaires for staff. After emerging in the 1990s, RCSAs have become commonplace and are recommended by most regulators around the world. In the last few years, most banks in Hong Kong have adopted a workshop approach to the RCSA process, which helps them both identify risk and educate staff on risk management.

- Reports to management following risk management exercises should include such information as critical operational risks based on KRIs and RCSA exercises, audits and compliance review reports, major risk events and losses, status and effectiveness of actions taken, and any exceptions.

- Operational risk events and factors can be categorised in different ways. Several meaningful ways to categorise risk include the location of impact, the source of risk, where the control responsibility lies, by the loss account that will bear expenses and write-offs, or by regulatory or internal conventions.

- The BCBS has developed an operational risk matrix that correlates seven separate loss events with eight different business lines which, when combined, offer a picture that covers 56 different operational risks for banks and financial institutions.

- The business lines outlined in the top-level mapping recommended by the BCBS are corporate finance, trading and sales, retail banking, commercial banking, payment and settlement, agency services, asset management, and retail brokerage.

- The top-level risks that the BCBS recommends mapping with internal loss data are internal fraud; external fraud; employment practices and workplace safety; client products and business practices; damage to physical assets; execution, delivery, and process management; and business disruption and system failures.

Key Terms

Study Guide

Further Reading

Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis. Chapter 4. In print.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk; June 2011.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards; Comprehensive Version, Annex 8

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001). In print.

Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Operational Risk Management in Supervisory Policy Manual. Web. 27 July 2010. <http://www.info.gov.hk/hkma/eng/bank/spma/attach/OR-1.pdf>

1 Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007). Ch. 4.

2 Bank for International Settlements; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk; June 2011. Pg. 11.

3 Hong Kong Monetary Authority; Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; November 2005; Pg. 23 – Section 7.

4 Bank for International Settlements; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk; June 2011. Pg. 12.

5 Level 1 business lines as identified in Annex 8 of the Basel II document issued in 2006. These include corporate finance, trading and sales, retail banking, commercial banking, payment and settlement, agency services, asset management and retail brokerage.

6 Bank for International Settlements; Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk; June 2011. Pg. 8.