Chapter 7

Risk Control and Mitigation

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Discuss interventions to deal with operational risk and how these interventions are grouped

2 Outline the role of loss prediction, prevention, control, and reduction

3 Outline the importance of internal control and governance on operational risk management and the role of regulators

4 Describe and explain assumptions, avoidance, and transference of risk and the role of insurance in mitigating operational risk

5 Outline the importance of contingency planning

Introduction

Identifying and measuring risk and determining the scope and objectives of a bank are only the beginning of the operational risk management strategy. These steps represent a passive analysis of risk. It is then necessary to take, as well as active steps to mitigate and control risks. There are a broad range of possible interventions depending on the ultimate goal, from avoiding risk completely to predicting and preventing risk or managing the losses associated with risk events to keep them within acceptable limits.

Strong internal controls and governance are key to mitigating and controlling risk. Without an effective operational structure, an operational risk management programme is doomed to fail. After having analysed and categorised and planned and put in place an appropriate governance structure, banks and other AIs can decide on how best to avoid, mitigate, or transfer risk. Here again, there are various options and approaches, which we discuss in this chapter. Banks have to decide on an acceptable level of loss and compare that with the expense of putting control mechanisms in place. Banks also have to outline their risk management plans to regulators, who make regular but subjective assessments of the plans to determine their fitness and set appropriate capital charges.

Banks may or may not be able to avoid risks altogether. At times they may have to make a choice between keeping the risk or keeping a business line. At other times, a bank may have to work with regulators and make assumptions for what is the right level of risk. They may also choose to transfer risk, often through the careful use of insurance or alternatives like bonds.

Even with all this planning and mitigating, banks should have contingency plans in place. Contingency planning can help banks better deal with disaster events if, or when, they occur. This chapter deals with the practical and proactive aspects of risk management, building on the more passive aspects of operational risk management discussed earlier in the book. Later chapters will consider the role of reporting and other techniques to deal with operational risk management.

Incident Management

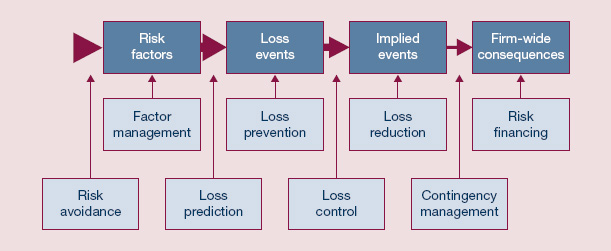

After setting scopes and objectives and identification, assessment, measurement, and analysis of the operational risks it faces, the bank is now ready to formulate and implement risk management actions aimed at risk mitigation and control. Depending on the results and findings from the three preceding steps, it can embark on interventions that may be grouped under the following broad categories:

- Risk avoidance by reducing engagement in the activities that expose the bank to identified operational risk or exiting them altogether;

- Factor management by modifying the operating environment in which loss events have been shown to arise;

- Loss prediction of the events that may cause future losses;

- Loss prevention by redesigning business activities and processes to make a loss event less likely to occur in the future;

- Loss control by changing the causal paths by which high-impact events happen;

- Loss reduction by reducing the impact of a specific event;

- Contingency management of the company-wide aftermath following major loss events;

- Risk financing to ensure that the bank is able to finance the losses.

Exhibit 7.1 shows a graphical illustration of these management responses to mitigating and controlling operational risks.

EXHIBIT 7.1 Generic risk management interventions

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), 322.

Risk avoidance and factor management can help banks avoid risk altogether. Most factor management methods try to improve the quality of resources used to identify, analyse and manage loss events. These techniques include quality management, personnel selection, training, culture management, and relationship management. Still, banks have to consider what operational risk events will take place and what the impact of those events will be on the bank’s operations.

Loss Prediction

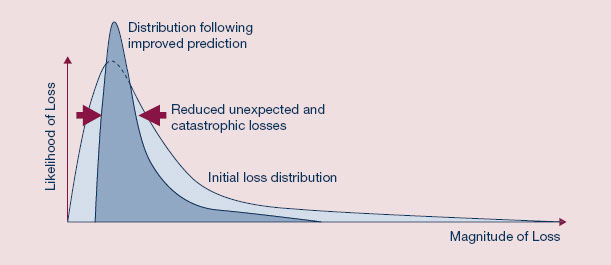

The goal of loss prediction is to reduce the uncertainty surrounding losses, that is, decrease catastrophic and unexpected losses. This is illustrated in Exhibit 7.2, which shows the ideal effects of loss prediction on the bank’s loss events distribution.

EXHIBIT 7.2 Ideal impact of loss prediction

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), 343.

Prediction does not only mean prediction of the expected level of losses or of a risk factor. Equally useful and often easier to obtain are better predictions of the volatility of risk factors or of the range of possible impacts. Similarly, estimation of the trends of risk factors and their future volatilities can help decrease the variance (and thus the unexpected losses and associated risk capital) associated with risky operations.

Prediction can be qualitative, as in marketing research on the possible demand for different new products, or quantitative, as in forecasting future market prices. In both cases, the bank arms itself with on-the-ground data that ideally should reduce the chances of business failure and thus of loss events. Quantitative prediction is only viable for events for which either the causes are at least partially understood or are relatively frequent. Simple fault tree models and time-series and regression models can be used for loss prediction of events related to financial, labour, and product markets.

Qualitative business techniques that utilise various forms of loss prediction include strategic and business planning, organisational learning, business and market intelligence, and project risk management.

Loss Prevention

Loss prevention refers to the activities that make a loss event less likely to occur. Most of these activities seek to redesign certain aspects of operations, making them less likely to have problems in future. Loss prevention has the effect of reducing the frequency rather than the severity of losses. It is most appropriate for high-frequency events because of its large marginal effect on the risk. However, even in general, if loss prevention can be performed, it is invariably more effective than loss reduction because it attacks the problem at the source rather than just address the symptoms of failure.

Loss prevention changes loss distribution by affecting the distribution of loss-event frequency. For the most part, loss prevention changes the expected frequency directly (and therefore the expected losses) and only indirectly affects the variance (and therefore the unexpected losses). Fortunately, decreasing the mean level of the frequency also tends to decrease the variance of aggregate losses; hence, the unexpected loss tends to decrease as a side effect.

Several management activities fall (more or less) under loss prevention. They include process reengineering, work and job restructuring, product and service redesign, functional automation, human factors engineering, fraud prevention and detection, enterprise resource planning, and reliability-based maintenance.

Loss Control

Loss control curbs the tendency of relatively frequent and insignificant events to become more critical. It does not prevent the underlying cause, but it does prevent any critical implied events (which will have much greater impact) from occurring. Loss control therefore has the effect of decreasing the frequency of major loss events with only a limited effect on their impact.

Compared with loss prevention, loss control is less cost-effective for operational events, but more effective for higher-impact events. Compared with loss reduction, loss control is less cost-effective for the high-impact events, but more effective for more likely events. As such, it provides a useful compromise between reducing the impact and reducing the likelihood.

Loss control has its own costs. When loss control measures are allocated to the expected losses associated with the event, they may actually increase expected losses beyond their original levels, at least initially. This is because loss control typically includes the implementation of new processes and programmes such as redundant systems, diagnostic controls, compliance programmes, inventory management and buffering, computer security management, physical security management, internal and external audit, and quality control.

Loss Reduction

Loss reduction involves activities that mainly reduce the severity—but do not affect the frequency—of losses. Loss reduction changes loss distribution by affecting the distribution of the impact of loss events. The extent that loss reduction affects the standard deviation of the impacts also largely determines its effect on unexpected losses.

Loss reduction activities are usually appropriate for external events, the occurrence (and therefore, frequency) of which is difficult or impossible for firms to manipulate. Loss reduction takes two approaches. It decreases the impact of the event before it occurs by planning of one form or another, for example, loss isolation, disaster, and contingency planning. Secondly, it reduces losses after the event by effective crisis management.

Assumptions, Avoidance, and Transference

Speaking in 2004, Alan Greenspan, then Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, noted that “it would be a mistake to conclude that the only way to succeed in banking is through ever-greater size and diversity. Indeed, better risk management may be the only truly necessary element of success in banking.”1 Greenspan was talking years before the collapse of subprime mortgages in the United States and the global financial crisis that followed from 2008. At the time, the Basel II policies on operational risk management were still in relative infancy. Years later, however, the truth of his comment has become self evident. If they cannot avoid risk, after all there is inherent risk in just about any bank operation, risk managers should seek to limit it.

Meeting the HKMA’s standards, ensuring strong risk management, and limiting complex and potentially expensive system reviews are certainly goals for operational risk managers and the management of a bank. The overarching goal, however, is to minimise or avoid losses that can impact both the operations of the bank and its customers. One sure—albeit difficult to measure—way to minimise losses is to avoid risks altogether.

Risk Avoidance

Banks can choose to avoid potential exposures to loss by reducing the levels of their risky activities or abandoning the business line, service, internal process, or customer group. Various stakeholders are involved in this decision. Systematic operational risk management techniques offer a means to lift the discussion from the level of turf battles and management instincts to more objective criteria based on risk-based performance measures.

At issue is whether the financial institution has a comparative (not necessarily an absolute) advantage in managing the risk over its customers, counterparties, and competitors, and that the risk is thus most controllable by the firm in question. The more uncontrollable the risk, the more likely the firm will want to avoid the risk. However, if the markets are rewarding the bank for taking the risk, as evidenced by its high stock price, then risk avoidance is probably not appropriate.

Business exit or abandonment (rather than decreased levels of business) can be justified in one of three ways. First, an inability of the business to make profits to cover expected long-term average costs. Second, the absolute level of risk: does the current level of capital allow handling of a catastrophic risk exposure? Third, risk-based return can justify an exit; in other words, even if the bank can handle the exposure, the marginal risk—the difference between the company’s stand-alone risk with the business and without it—should be justified by the return.

Reducing the level of risky activities makes sense for investments whose marginal costs in terms of additional transactions or customers are relatively high, uncontrollable, or uncertain. If the marginal cost of an additional customer or transaction exceeds the marginal revenue of the transaction, then the level of that activity should be lowered. In computing these marginal costs, the risk capital costs associated with the transaction’s marginal effect on the firm’s stand-alone risk should be included.

There is a cost to risk avoidance. The direct cost of a business exit is the foregone income that may have been obtained from that activity. There are other costs. Marketing and sales may resent giving up a risky but potentially profitable business, and this may lead to a loss of staff. Important stakeholders (unions, managers, and government) other than shareholders might have legitimate concerns about an exit, and may use their political power to stop it. Economies of scale and learning as well as synergies across different business areas may be lost. The decision to avoid a risk may also cause other risks (such as legal liabilities).

Risk Assumptions

While the management of operational risk is, certainly, the responsibility of banks and other AIs, regulators take a keen interest in the strength and evolution of operational risk management structures in each institution. Bank failures, although rare, have happened and when they do, they have significant spill-over effects on much of the rest of society. As a result, regulators—in this case the HKMA—review operational risk management structures, choices, capital charges, and other aspects on a regular basis. Because these reviews are often subjective, it is a good idea for banks to have a clear rationale for every choice.

The injection of judgemental considerations in the formal risk assessment process adds more nuance and calibration to the composite risk profile that HKMA case officers build for each significant activity undertaken by a bank or AI.

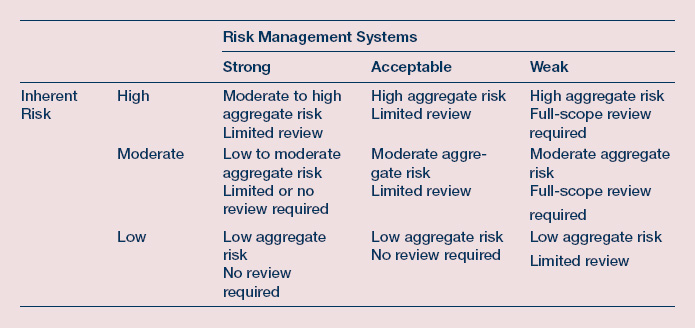

Exhibit 7.3 shows a risk profile matrix that correlates the examiner’s assessment of the inherent risk of a bank’s activity with the strength of the same bank’s risk management system in relation to that particular activity, and the supervisory response deemed appropriate for each particular set of assessments.

EXHIBIT 7.3 Risk profile matrix

Source: HKMA

Risk assumptions are useful to develop models and operational risk management frameworks as well as contingency plans. They are also an important part of the HKMA’s regulatory approach to operational risk management.

As Exhibit 7.3 illustrates, just because the examiner measures the inherent risk of a particular banking activity a high in aggregate does not automatically mean that a full-scope review will be undertaken. In this situation, if the risk management system is judged to be strong in relation to that particular activity, then the supervisory response can be one of limited review.

If the inherent risk is judged to be low and the risk management system is strong, then no review will be required. But if the examiner judges that the inherent risk is low but the risk management system is weak, then a limited review may be in order. A full scope review will be undertaken if the inherent risk is judged to be moderate or high, and the risk management system is weak.

How does the examiner assess the inherent risk of a banking activity? The HKMA defines inherent risk as the “probability and degree of potential loss due to an adverse event or action within a particular activity or product without regard to the adequacy and quality of the relevant risk management system in place.” Assigning a level of inherent risk (whether high, moderate, or low) to a particular activity or product is essentially a judgement call that the examiner makes after assessing and weighing all the relevant factors and evaluation criteria.

For example, the writing and purchasing of credit default swaps require sophisticated skills and deep experience. The inherent risk in this activity is therefore high in terms of operational risk (because recruiting and keeping such specialised talent can be difficult and expensive), and in terms of credit risk (the counterparties must be carefully selected), reputational risk, and legal risk, among others.

The next step is then to assess the adequacy of the risk management system as it applies to the activity of writing and purchasing credit default swaps. The examiner looks at the four elements of a sound risk, management system as it applies to the activity being examined:

- Is there active board and senior management oversight over the writing and purchasing of credit default swaps?

- Are there effective organisational policies, procedures, and limits for managing the process?

- Are there adequate risk measurement, monitoring, and management reporting systems?

- Are there comprehensive internal controls, including an effective internal audit function, for the particular activity?

Depending on the answers, the bank examiner will decide whether the risk management system is strong, acceptable, or weak. Following the risk matrix, a determination is then made on the appropriate supervisory response (whether no review, limited review, or full-scope review).

Risk Transference

The way a business is financed affects its ability to survive catastrophic losses. Risk financing involves either transferring the loss to some external party better able to manage the risks for a fixed premium, or restructuring the organisation to be able to handle the risk. Alternatively, firms can decrease the likelihood of default directly by internal restructuring.

There are several approaches to financing losses:

- Financial restructuring. Debt is the cheapest form of external financing, and can allow firms to capture tax benefits, as well as important economies of scale and scope. Increased debt, however, means an increased risk of default. Techniques such as credit management and asset-backed financing help manage the trade-off by restructuring both long- and short-term liabilities.

- Asset-liability management. Focusing on restructuring the portfolio of assets and liabilities helps minimise sensitivity to liquidity and interest-rate risks.

- Corporate diversification. Acquisitions or investments in other firms or projects whose cash-flows are not perfectly correlated with the firm’s other cash-flows can decrease the total risk of the firm’s net revenues.

- Insurance. An external insurer promises to provide funds to cover specified losses in return for a premium from the purchaser at the inception of the contract.

- Hedging. Financial derivatives are used to offset losses occurring from movements in interest rates, commodity prices, and forex rates.

- Contractual risk transfers. Risks are transferred using contracts, for example by outsourcing or using independent contractors.

Insurance

Under Basel II, banks can qualify to make deductions from the operational risk capital charge if they participate in risk-transfer activities such as insurance. Currently, the recognition of insurance mitigation is limited to 20% of the total operational risk regulatory capital charge calculated under the advanced measurement approach (AMA). Banks are required to have well-reasoned and documented frameworks for the insurance to be recognised and, to comply with Pillar III, must publicly disclose their use of insurance for mitigating operational risk.2

In addition, according to the Bank for International Settlements, “the risk mitigation calculations must reflect the bank’s insurance coverage in a manner that is transparent in its relationship to, and consistent with, the actual likelihood and impact of loss used in the bank’s overall determination of its operational risk capital.” The insurance company must also have at least an “A” rating or its equivalent, and the insurance coverage must be consistent with the actual likelihood and impact of loss used in the bank’s overall determination of its operational risk capital.

A bank is expected to hold sufficient reserves to cover losses up to the VaR amount, but it may be unable to absorb the catastrophic loss we referenced earlier. Still, if the bank has an insurance policy against some aspects of operational risk, that could absorb at least part of a catastrophic loss. According to the BIS, “insurance could be used to externalise the risk of potentially ‘low frequency, high severity’ losses, such as errors and omissions (including processing losses), physical loss of securities, and fraud. The Committee agrees that, in principle, such mitigation should be reflected in the capital requirement for operational risk.”

The traditional insurance products to cover aspects of operational risk include the following:

- Fidelity bond coverage. This can cover a bank against losses stemming from dishonest or fraudulent acts by employees, burglary, or unexplained disappearance of property, counterfeiting, and forgery. This coverage is also known as financial institution blanket bond or bankers blanket bond coverage.

- Directors’ and officers’ liability coverage. This can protect against losses incurred by directors and officers for wrongful acts and losses by the financial institution for money it paid to directors and officers to indemnify them for damages.

- Property insurance. This can protect firms against losses from fire, theft, inclement weather, and so on.

- Electronic and computer crimes insurance. This covers intentional and unintentional cases involving computer operations, communications, and transmissions.

In 1999, Swiss Re and London-based insurance broker Aon introduced what they called the Financial Institutions Operational Risk Insurance (FIORI), which aggregates several sources of operational risk into a single contract. The policy covers physical asset risks, technology risk, relationship risk, people risk, and regulatory risk.

FIORI’s coverage includes a number of operational risk causes:

- Liability: Losses resulting from neglect of legal obligations by the financial institution or one of its subsidiaries, management, or staff members, representatives, or companies to which the financial institution has outsourced some functions.

- Fidelity and unauthorised activities: Dishonesty as defined in the insurance policy; all trading business; potential income lost; repair costs.

- Technology risks: Sudden and irregular failure of own-built applications, but normal processing errors not covered.

- Asset protection: All risks concerning buildings and property; own and trust assets.

- External fraud: Term is broadly defined and coverage extends beyond existing customers; potential income not excluded.

The insurance policy has a deductible of US$50 to US$100 million per claim, meaning that it will pay out only for amounts beyond that deductible. The premium ranges between 3% and 8% of the covered amount, which means that if operational risk in the amount of US$100 million is insured, the premium would be US$3 million to US$8 million.

The FIORI policy highlights one drawback of insurance: high cost. While it is possible to insure the bank against operational risk, there are limitations to operational risk insurance as a risk-management tool. These include:

- Policy limit. After the insurance policy deductible is met, further operational losses are covered up until the policy limit. Losses exceeding that limit are borne by the bank and could threaten its solvency. Linda Allen, Jacob Boudoukh, and Anthon Saunders in their 2004 book note that the combination of comparatively high deductibles and relatively low policy limits has resulted in only 10% to 13% of operational losses being covered by an insurance policy.

- High cost. Premiums are costly. According to Christopher Marshall in his 2001 book, less than 65% of all bank insurance policy premiums have been paid out in the form of settlements.3

- Moral hazard. While insurance is one way to diversify operational risk, there is always a possibility that the knowledge of protection may lead to a laxity in prevention, with possible unfortunate results. That in turn may lead to high premiums and negotiation costs. Exante moral hazard can occur in the form of increased negligence by the management towards operational risk. Expost moral hazard is concerned with biased reporting because of a difficulty in measuring actual losses.4

- Other limitations. These relate to speed of insurance payouts, loss adjustment, limits in product range, and inclusion of insurance payouts in internal loss data.

Alternatives to Insurance

So what are the alternatives? Hedging is one possibility, using derivatives such as catastrophe options and issuing catastrophe bonds.

- Catastrophe options: Known simply as cat options, they are linked to the U.S. Property and Claims Services (PCS) Office national index of catastrophic loss claims and trade on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Cat options can be written on outcomes due to catastrophic loss of a firm’s reputation, outcome of a lawsuit, an earthquake, weather, and so on. They trade like a call spread, combining a long call position and a short call position at a higher exercise price. If the PCS index falls between the two exercise prices, then the option-holder receives a positive payoff.

- Catastrophe bonds: Known as cat bonds, they can be used to hedge against catastrophic operational risk by issuing structured debt. The principal is exchanged for periodic coupon payments, where payment of the coupon and return of the bond principal are linked to the occurrence of a pre-specified catastrophic event. A flexible structure gives cat bonds an edge over cat options.

Internal Controls

Internal controls are measures that banks can implement to spot or determine risk exposures and prevent them from turning into loss events. An example of an internal control is limits on dealers. Technically speaking, the limit is in place to control the risk exposure. There are hundreds or thousands of internal controls in any bank. Internal controls are mechanisms that banks put in place to limit exposures. In terms of operational risk, the board of directors sets internal controls as part of the operational risk management framework. KRIs, discussed earlier, are often used within this system of internal controls. The aim of internal controls is to help the bank meet its performance objectives while limiting risk and ensuring compliance with laws and regulations. In other words, internal controls are useful tools to manage operational risk but that is by no means their sole purpose.

In 1998, the BCBS noted that a “system of effective internal controls is a critical component of bank management and a foundation for the safe and sound operation of banking organizations”. 5

Internal controls apply to a wide range of activities, from the limits set on dealers mentioned above to monitoring devices used on system applications from accounting systems to ATMs. There are different types of internal controls. Two common types are detective controls and protective controls.

An example of a detective internal control might apply to IT systems and, for example, the flow of information between automated teller machines and the bank’s own accounting system. An internal control system might keep track of the process of information feedback between an ATM and the accounting system. The control might set a limit on the time it takes for the information to feed back. If that time limit is breached, a log might be generated and the information passed to the right supervisors. This is an example of a detective control. It does not, on its own, limit losses but it would alert the bank to a potential exposure.

Protective controls are more proactive. An example of a protective control is withdrawal limits on ATM cards. In the case a card is stolen or a fraud against a customer or the bank is perpetrated using a bank card and an ATM, the withdrawal limits would cap the potential loss to both the customer and the banks. Other measures, such as chip identification or the use of personal identification numbers (PINs) are other examples of protective controls.

The ultimate aim of an internal control is to prevent a particular loss event from ever happening. The controls are often put in place at a risk location, to limit risks and minimise losses associated with operational risk.

The 1998 framework put forth by the BCBS outlines a series of activities associated with internal controls and 13 overarching principles that match, in broad strokes, the principles that the BCBS later put forward to deal with operational risk management. At the top of the list (Principles 1 through 3) are the roles of the board of directors and senior management. The former is responsible for approving and reviewing business strategies and ensuring the right control policies are in place along with the right ethical and integrity standards. The latter, senior management, is responsible for implementation.

An effective control system helps the bank continuously recognize and assess risks of all types—credit risk, country risk, transfer risk, market risk, interest rate risk, liquidity risk, operational risk and legal risk, to name a few (Principle 4). Key to their effectiveness is their integration into the daily operations of the bank (Principle 5).

To do this, however, requires a series of activities. For starters, an effective control structure has to be set up and controls defined at every business level and department. At the same time, duties should be segregated so that staff are not both controlled and controllers. Failures in this account have resulted in huge loss events, such as the massive trading losses associated with rogue traders at Barings Bank, SocGen, and UBS since the late 1990s.

Key to the process is information, which should be “reliable, timely, accessible and provided in a consistent format.” This information should be comprehensive, spanning the range of bank operations. It should also move easily across multiple channels and understood by all the appropriate personnel (principles 7 through 9).

Finally, internal controls should be regularly monitored and audited, and deficiencies quickly reported to management and even the board of directors (principles 10 through 12). Regulators also have a role to play. It is up to them to ensure banks have effective internal controls that match their size and complexity of their operations as well as their risk appetite and tolerance (principle 13).

Contingency Planning

The aim of contingency planning is to prevent a business disaster when a company is hit by a rare event, and to provide continuity of operations until a return to normal functioning. Contingency planning does this by first identifying the company’s key business processes and the likely threats to them. Based on this information, a plan is developed to ensure those processes continue regardless of the circumstances.

Most operational contingencies result from events that affect operations and thereby threaten business continuity. Although some operational contingencies are internal (the result of human and technological failures), most are external, resulting from the failure of the infrastructure on which the business depends. Being far harder to control, external operational failures require well-developed contingency plans.

Contingency plans should be evaluated according to three criteria:

- Reliability, the degree of protection provided by the plan against major unexpected events affecting the business plan;

- Availability, the time it takes to return to normal business functioning; and

- Plan maintainability, the cost and adaptability of the plan to changes in resources and processes.

The quality of a contingency plan is proportional to the time and effort staff have put into it. Contingency planning can be expensive so obtaining resources for it can be difficult. Managers will never be congratulated for a well-thought-out contingency plan if the event does not occur. Contingency planning is reliable only as far as the known risks it accounts for. The problem is that risk managers may not take extreme events into consideration or consider them too unlikely to plan against. This was seen during the bombings of the World Trade Center in the 1990s or after the tsunami that hit Japan in 2011. As the operations of banks get wider and more complex, spanning multiple countries and with complex technical and financial requirements, contingency planning gets more complex because the planners have to seriously and realistically consider risks that, not that long ago, may have been unthinkable.

Summary

- Operational risk management interventions can be grouped in eight broad categories that include risk avoidance, factor management, loss prediction, loss prevention, loss control, loss reduction, contingency management, and risk financing.

- The goal of loss prediction is to eliminate uncertainty of losses, which in turn can decrease catastrophic and unexpected losses. Prediction can be qualitative or quantitative, but quantitative prediction is really only viable when causes are understood or frequent.

- Loss prevention activities are aimed at making loss events less likely. The aim of most of these activities is to redesign aspects of a banking operation to eliminate future problems.

- Loss control aims to curb relatively frequent and individually insignificant events before they become critical. Loss control has its own costs and typically does not address the underlying causes and may, at the beginning, even increase expected losses.

- Loss reduction aims to reduce the severity of losses associated with loss events, even if it doesn’t affect the frequency. Loss reduction activities are typically most appropriate for external events that banks may not be able to manipulate.

- Strong internal governance and internal controls are key to effective operational risk management. Typically, they are designed to ensure risk management activities are built into day-to-day business in an efficient and effective manner while guaranteeing reliable, timely, and complete information.

- The HKMA says operational risk management requires the attention and involvement of a wide variety of organisational components. A dedicated operational risk management committee with a direct line of reporting to the board of directors is an important part of this process.

- The board of directors has the ultimate responsibility for operational risk management. It should understand risk exposures, define a strategy to deal with it, approve the risk management framework, review reports, ensure the implementation of policies, and ensure compliance with disclosure requirements.

- The HKMA puts the onus on senior management to implement the operational risk management strategy approved and supervised by the board. This includes developing policies, processes, and procedures, defining a structure for operational risk management, assigning responsibilities and reporting relationships, ensuring the right staff has the right level of authority to deal with risks, assessing the appropriateness of risk management processes, and making sure the right technical resources are used.

- It has become standard practice for banks to have a dedicated and centralized risk management function to help senior management understand and manage operational risk.

- Business line management is accountable for day-to-day management and reporting of operational risk specific to their business units. Management of a business line should be independent of the central risk management function.

- Internal auditors provide independent assessment of the operational risk management framework. Banks should ensure the right audit coverage is in place.

- The HKMA expects banks and other AIs to nurture a positive risk culture using factors such as clear communication, consistent messaging from management, assigning risk management activities, inclusion of risk management considerations in remuneration, and creating a free and open environment that allows staff to speak about risk problems without fear of negative consequences.

- Regulators regularly examine the operational risk structure of banks to determine if they are strong, acceptable, or weak. Risk assumptions are useful to develop models and plans and are key to the HKMA’s approach to operational risk.

- Banks can also work to transfer risk through financial restructuring, asset-liability management, corporate diversification, insurance, hedging, and contractual risk transfers.

- Insurance products such as fidelity bond coverage, directors’ and officers’ liability coverage, property insurance, and electronic and computer crimes insurance all help tackle operational risk. But insurance, can be expensive and there are limits to the use of insurance as a risk management tool. Options to insurance include catastrophe options and bonds.

- Contingency planning should be evaluated based on three criteria: reliability, availability, and plan maintenability.

Key Terms

Study Guide

Further Reading

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001). In Print.

Linda Allen, Jacob Boudoukh and Anthon Saunders, Understanding Market, Credit, and Operational Risk: The Value at Risk Approach (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004).

Hong Kong Monetary Authority, OR-1: Operational Risk Management in Supervisory Policy Manual.

1 As quoted by Naresh Makhijani and James Creelman; Creating a Balanced Scorecard for a Financial Services Organization; Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 2011; Ch. 1.

2 Only banks permitted by their national regulator to use AMA to calculate the operational risk capital charge are eligible for this treatment.

3 Linda Allen, Jacob Boudoukh and Anthon Saunders, Understanding Market, Credit, and Operational Risk: The Value at Risk Approach (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004).

4 Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2001).

5 BCBS; Framework for International Control Systems in Banking Organizations; September 1998; at www.bis.org/publ/bcbsc131.pdf.