Chapter 2

Operational Risk Management Frameworks

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Understand the evolution of operational risk management regulation and the four general components of an operational risk management framework

2 Understand the process of effective operational risk management and the five broad steps involved

3 Outline the best practice principles that underpin an effective operational risk management framework

4 Understand the different impacts of low and high frequency events and some initial strategies that may be universally applicable

Introduction

Having broadly defined operational risk, its causes, and approaches to manage it, this chapter begins to delve deeper into the operational risk management process by discussing operational risk management frameworks and considering the regulatory backbone behind them.

This chapter starts by discussing the broad steps in the process, which include defining scope and objectives, identifying and assessing risks, mitigating and controlling risks, and monitoring and reporting. We then break down these steps into their component parts and start peeling the layers and considering best practices in their implementation.

Although later chapters will explore these concepts at greater length, here we will lay the foundations upon which operational risk managers can build a management framework for operational risk and how this framework fits into the operations of a bank or AI.

Operational Risk Management Frameworks

In 1997, the U.S. Federal Reserve issued its Framework for Risk-Focused Supervision of Large Complex Institutions. It was one of the earlier supervisory guidelines with an eye on developing a framework to manage operational risk. The BCBS put forth its first set of principles in 2001 and built on them in 2006. The HKMA has also issued guidelines on how banks or AIs should develop operational risk management frameworks. The HKMAs guidelines are based on the BCBS principles.

In its 2005 Supervisory Policy Manual for Operational Risk Management, the HKMA notes that operational risk management has evolved into a functional discipline with dedicated staff that set out formal policies, processes, and procedures. This change is “driven by a growing recognition by the Boards and senior management of the need to address operational risk as a distinct class of risk.” Every organisation has a unique operational risk profile that requires a tailored approach that fits within the size and scale of the institution.1

An appropriate operational risk management framework includes four general components2:

- Organisational structure including board oversight, senior management responsibilities, roles of business line management, an operational risk management function, and internal audit;

- Risk culture;

- Strategy and policy; and

- Processes to identify, assess, monitor, control or mitigate and report operational risk.

In broad strokes, the HKMA expects AIs to develop appropriate frameworks to manage operational risk to ensure that these risks are “consistently and comprehensively identified, assessed, mitigated/controlled, monitored and reported.”

The size, complexity, and resources of the organisation are important factors in making decisions about the scope and objectives of operational risk management. For example, it may not be worth the effort for smaller banks to estimate the probability of distribution of every possible loss. The area of focus is typically catastrophic loss, since small institutions do not have the large capital buffers or lines of credit to absorb such huge losses.

However, every organisation is different and so the scope and objectives of operational risk management must also take into account factors unique to the institution, such as the risk appetite of the board and senior management and the availability of skills and management structures to conduct effective operational risk management.

The agenda for operational risk management must first be clearly defined. This is a task that is not as simple as it sounds. Operational risk management covers all business areas and each one typically has its own agenda. This is one reason why the board of directors, as representatives of the shareholders, and senior management should set the risk management agenda. If the bank’s appetite for risk is set by the top of the organisation, everyone else down the chain would have to abide by it.

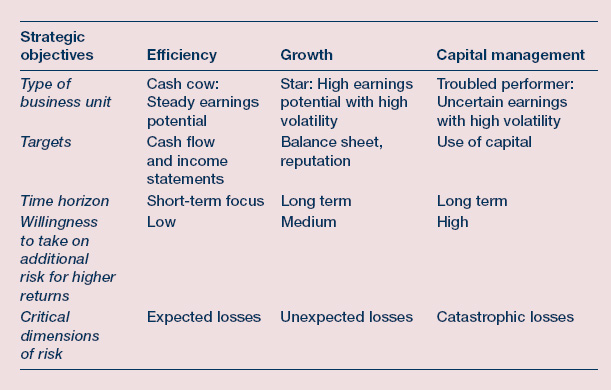

In general, the bank’s top leadership should align exposure to risks with the bank’s strategy and core competence. This does not mean that every unit has to have the same risk agenda. For example, business units regarded as reliable performers or “cash cows” should focus on curtailing expected losses to ensure they remain competitive. On the other hand, business units with high potential should focus on unexpected losses, which might derail their growth. Troubled business units should look for turnaround or exit strategies and make safeguarding of investor capital their priority. These alignments are illustrated in Exhibit 2.1.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Business strategy and risk

Christopher Marshall, Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions (Singapore: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), 129.

Operational Risk Management Process

We can divide the process of operational risk management into the following broad steps:

- Defining the scope and objectives of the programme. This first step is the responsibility of senior management in consultation with the board of directors. The objectives—typically involving efficiency, change management, capital management and growth—will depend on the broader business strategy, which may vary from one business line to another. Operational objectives should be based on a frank assessment of an appropriate yardstick of internal or external best practices, and should be followed by a series of intermediate targets designed to bring operations up to the level of the benchmark.

- Identifying and assessing critical risks. With support from senior management, staff compile information about critical processes, resources, and loss events within the organisation. Operational risk management often becomes ineffective because it tries to be too inclusive; the focus should be on the precise objectives set by senior management. The key operational risks in key processes and resources must be gauged based on information gleaned from interviews, surveys, historical data, and other sources.

- Measuring and analysing risk. Operational risk management should form a reasonable and defensible judgment of the seriousness of any risk with regard to both the magnitude of the impact on the bank and the probability that the risk will occur. If it is not possible to quantify the risks, the bank may still identify their potential causes and take steps to mitigate those risks. A risk estimate should incorporate important dependencies among the different risks, and look at the aggregate effect of losses, particularly operational events.

- Mitigating and controlling risk through management actions. Evaluation of different management interventions is imperative to deal with potential risks, either singly or across the business. A decision must be made on whether to accept or avoid certain risks, and how to manage key risk factors that affect the bank’s profit and loss. Management actions may also involve developing a capability to forecast or prevent future losses and check their growth over time or reduce their impact. Management may decide the risks are inherent to the business and opt to either mitigate or offset the impact of potential losses through risk financing.

- Monitoring risk with regular reporting to management. This enables a continual evaluation of the performance of operational risk management, and a re-assessment of potential risks. Ongoing monitoring is particularly important because a risk environment can change swiftly due to product and market innovations, and the reliance on open networks such as the Internet.

Best Practice Principles

There are several best practice principles to keep in mind when defining the scope of operational risk management activities.

- It is advisable to start small. Focus on key processes and resources, and the riskiest scenarios. Keeping in mind the Pareto principle (also known as the 80:20 rule) helps to concentrate on what counts; even for complex processes, the majority of losses will come from a handful of potential loss events. Focusing on a multitude of potential loss events is too complex, and ultimately likely to be unsuccessful.

- Start where the resources are. To be effective, operational risk management must have considerable financial and other support. A programme should therefore start where the support is, support such as available staff, data, and systems. If the resources sit with select operations managers, work with them to prove the concept and then roll it out to other businesses. It is essential that these line managers understand the programme’s objectives, and how it affects their daily business.

- Focus on areas not partially covered by other control or audit activities. Excessive overlap with other areas, particularly audit, operations management, and financial-risk management, could result in turf battles or an unwillingness of business units to work with the operational risk group. Avoid this by co-opting any potential opposition. Go bottom-up and top-down simultaneously. Purely top-down is unwise, as the data and knowledge required for risk-management analysis typically would sit with business line managers. Their support is vital in implementing any processes. Purely bottom-up is equally fallible, as support from senior management is critical to even get started.

- Be opportunistic. A project plan should be both strict enough to gauge progress and flexible enough to take advantage of data and access opportunities to line managers. Planning ahead and preparing for interviews and discussions will ensure regular deliverables with immediate value.

Once the top leadership’s risk management agenda and the general scope of the risk management project are defined, senior managers develop high-level financial and operational risk targets for each business unit. Financial targets typically come first. For example, financial targets for business units with steady earnings potential will focus on optimising operating cashflow and reducing variation in the income statements. Business units with greater operational risks will require more balance-sheet protection and more careful management of scarce risk capital.

Following the principles above makes it easier to achieve these goals.

Managers should start small and avoid trying to tackle very single risk in one fell swoop. It makes sense to focus on high frequency exposures or large loss events. For retail banks, for example, customer transactions are likely to represent a significant portion of the business, so the focus should be there. Banks use this approach to their business on a regular basis. Starting small also means focusing the resources and energy of the organisation in what it is good at. Banks may, for example, divest themselves of units that generate little or no income relative to the risk or that are so far outside the remit of their business as to make risks difficult to understand and tackle. The same may be true of operations. Information technology needs, for example, may be outsourced to experts rather than handled in house. When it comes to operational risk, similar principles apply: Focus first on what you know best, which is generally the larger business operations. For example, in a commercial bank, a risk manager would likely pay more attention to transactions that represent the bulk of the bank’s business such as trade finance and less on operations of savings accounts that have less activity and generate less revenue. The goal is to mitigate risks that you can identify and actually deal with while prioritising the use of resources.

At the same time, risk managers should focus on where the resources are and work to focus the resources where the risks are greater. For an investment bank, for example, limiting exposures among traders may be a greater priority than controlling every aspect of transactions with retail customers. A couple of factors come into play here. First, risk managers should identify and focus their energy on the big areas. Second, senior management has to know where the risk is greater and, in turn, where to allocate limited resources for risk management operations. Some discretion is in order. For example, a bank’s call centre may generate little or no revenue for the bank, but its value in terms of limiting operational risk by tracking customer interactions and managing customer relations and transactions may be invaluable, limiting potential exposures and losses.

It is also important to focus on areas that are not covered by other risk control activities. In practical terms, this might mean focusing on new ventures, introducing new products, or launching operations in new jurisdictions, all of which might have lax, young, or ill-defined controls for a series of risks.

Finally, risk managers should seize opportunities that present themselves to improve risk controls or implement more effective ones. One such opportunity might be the adoption of a new system, for example, the move from a manual accounting system to an automated one within a particular function or the adoption of a new electronic banking system that complements a pre-existing telephone-based one. The process of adoption itself might generate an opportunity for better risk management by using lessons learned in the first system while designing or operating the second, more modern one.

ORM Frameworks and Goals

Keeping the necessary components of an operational risk management framework in mind, the steps to develop the framework and best practice principles, organisations then outline operational targets that must be consistent with the financial targets. The aim of the operational risk management framework is to ensure that these operational targets are met and, in so doing, limit the risks to which the bank is exposed. Given the sheer breadth and depth of most banks today, this can be an extremely complex undertaking, one that can span myriad skill-sets and require input from risk managers in various fields. Balance-sheet protection, for example, implies targeting value-at-risk and an estimate of unexpected and catastrophic losses, while income statement management focuses on earnings-at-risk, particularly the expected and unexpected component of the risk.

In general, a single bank will have multiple operational risk management plans for its multiple units or divisions. Each one will go through a similar process and require a similar set of decisions at each stage. Often, the structure of the plan will be partly determined by the maturity of the division or unit and the level to which various factors that affect operational risk management are developed. For example, the focus of an ORM framework for a unit with a strong operational risk culture and well-developed processes is likely to be different from that of a new division with untested operations. At this stage, then, managers will likely determine whether the focus of the framework and associated goals should be on frequent and low-impact events or very infrequent but very large impact events. If the operational risk-management project is for a relatively low-level business unit whose strategic objectives are greater efficiency and cost control, concentrating on frequent low impact events may be the appropriate course. On the other hand, if the business unit has a capital management agenda and is looking at risk-based capital allocation to cover operational risk, a focus on very infrequent, very large impact events may be more appropriate.

Regardless of what risk management targets and area of focus a bank decides to adopt, some initiatives can be very effective across all organisations. These universally applicable initiatives include the following:

- Increasing risk awareness. An operational risk management programme must sell the case for risk awareness to staff and managers of the business units. The programme should be seen as a helpmate, rather than a big brother. Measures to translate high-level risk targets into actionable initiatives include training and education to raise understanding of operational risks. Staff—in particular operational risk managers whose approval is essential to implement any change—should know why existing practices need to be changed. In the early stages, risk assessment may require extensive self-assessment of exposures by the business units. This makes it necessary for managers to learn the techniques of risk analysis and the limitations of more informal and subjective risk assessment.

- Proactive risk analysis. This should begin with data gathering (rather than complex model building) and the development of short-term deliverables of immediate value to line operations. Several intermediate targets can be used for further analysis, including naming and defining major loss events so that staff have a common language in which to discuss and analyse operational problems, and simulate risk-based resource allocation and scenario analysis.

- Risk-based performance measurement. Risk-adjusted measures of profitability such as return-on-risk adjusted capital help companies to assess the desirability of risk management efforts in specific business areas. The choice of target business variables depends on the risk and the importance of the business area to group profits and losses. Another important issue is the extent to which overhead operating costs are variable—this would suggest the importance of operational risk targets relative to financial and credit risk targets. For example, much of the variance in net income is the result of variance in the interest margin, and so at first glance this might not suggest the need for operational risk management. However, market risks are largely outside of the bank’s control; it cannot influence the central bank’s decision to raise interest rates, for example. What it can do is to anticipate and mitigate expected losses from such external developments, which is the province of operational risk management.

- Improvements in operational efficiency. Operational risk techniques such as dependency models offer managers a method to leverage internal knowledge about what can go wrong in their operations and why, and how to deal with the impact. Developing common definitions of loss events and risk factors is an important step in helping staff to discuss internal problems and to develop common approaches to cope. Building a standard set of processes helps to leverage the best practices in one business unit to standard practices within the entire company.

- Implementing a systematic change control process. One of the most cost-effective operational risk management interventions is the development of a systematic process of change control. Typically, a change management committee composed of the heads of the relevant business lines and staff functions monitor and manage the risks associated with major business, system, and product changes. A dedicated unit, perhaps in operational risk or internal control, rapidly disseminates notices of change to all who may be affected by it, given the difficulty of predicting some of the downstream impact of the changes.

- Developing operational limits. Limits should be put in place to monitor, constrain, and avoid risk exposures. Traditionally used for market risk where a variety of risks can occur in a variety of business units, limit structures range from the simple aggregate level to complex hierarchies. Operational risk limits are simpler because they are less dynamic and accurate data for operational exposures are poor. These risk limits are important nonetheless because they set the maximum risk tolerance of a company. Staff members are constrained from risk-taking beyond this threshold without prior approval. Limits should have associated well-defined action to be taken if the limits are exceeded. An action-tracking mechanism should ensure limit excesses are tackled promptly to prevent any fallout. Limits must be applied consistently, otherwise they are useless as staff realises the system can be circumvented.

Summary

- The HKMA’s Supervisory Policy Manual for Operational Risk Management considers the evolution of operational risk management and considers the emerging reality that boards of directors and senior managers at banks and financial institutions are increasingly required to take responsibility over operational risk management strategies.

- An operational risk management framework typically includes four general components: the organisational structure, risk culture, strategy and policy, and processes to handle operational risk.

- The process of operational risk management can be broadly divided into a number of steps. The first is defining the scope and objectives of the programme. The second is identifying and assessing critical risks. The third is measuring and analysing risk. The fourth is mitigating and controlling risk through management actions. The fifth is monitoring risk with regular reporting to management.

- There are a number of best practices to consider when defining the scope of operational risk management activities: Start small, start where the resources are, focus on areas not covered or partially covered by other control or audit activities, and take opportunities to address risk when they arise.

- A number of initiatives are universally applicable to the process of operational risk management. These included increasing risk awareness, focusing on proactive risk analysis, using risk-based performance measurements, improving operational efficiency, implementing system changes to control processes, and putting operational limits in place.

Key Terms

Study Guide

Further Reading

Hong Kong Monetary Authority. “Operational Risk Management” in Supervisory Policy Manual. Web. 28 November 2005. <http://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/doc/key-functions/banking-stability/supervisory-policy-manual/OR-1.pdf>

US Federal Reserve, “Framework for Risk Focused Supervision of Large Complex Institutions”. Web. 8 August 1997 <http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/SRletters/1997/sr9724a1.pdf>

Marshall, Christopher. Measuring and Managing Operational Risks in Financial Institutions. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2001. Print.

Taylor III, Bernard W.; and Russell, Roberta S. Operations Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2009. Print.

1 Hong Kong Monetary Authority; Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; November 2005; Pg. 9 – Section 3.

2 Ibid; Section 3.2.1.