Chapter 10

Regulatory Requirements

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Understand and explain the evolution of the Basel II capital accords and the three Pillars that frame their approach to operational risk management

2 Discuss the HKMA’s approach to setting the capital charge for banks and other authorised institutions

3 Explain the basic indicator approach, standardised approach, and advanced measurement approach to setting the capital charge for a financial institution

Introduction

We have already discussed, to some degree, the regulatory framework that guides operational risk management practices. In this chapter we discuss how regulators use this framework to calculate the capital charge that banks should set aside to protect themselves, and the industry, from loss events associated with operational risk factors.

The regulatory framework for operational risk is not only relatively recent but it is also evolving. In fact, while the BCBS of the BIS introduced the Basel II accords in 2004, which include extended discussion on how regulators can approach operational risk management at the banks in their jurisdictions, the standards have continued to evolve. In fact, a Basel III package is likely to be implemented in stages from January 2013. The HKMA adopted Basel II standards in 2007.

The Basel II accords are based on a three-pillar approach that we discussed earlier in this book. Here we explore each pillar in somewhat more depth, touching on the regulatory requirements for capital charge, regulatory principles for capital adequacy and, briefly, the role of market discipline and public disclosure.

We then move on to discuss the HKMA’s approach to regulation and exposure control and how the Hong Kong regulator uses a risk-based supervisory approach to make sure AIs are managing their risks properly.

The HKMA uses a detailed framework to set the capital charge for each bank and other AIs. Locally incorporated AIs in Hong Kong used one of two approaches. They either adopt the basic indicator approach (BIA) or the standardised approach (SA) to measure their capital charge for operational risk. A third approach that Basel II also considers, the advanced measurement approach (AMA), has not yet been introduced in Hong Kong at the beginning of 2013. The discussion of operational risk management in this chapter ends with a consideration of these three approaches.

Basel II

The regulatory requirements for operational risk management have become increasingly detailed over the last few years and in particular since the BCBS started putting more emphasis on operational risk management (ORM). The BCBS introduced the second set of accords, Basel II, in June 2004. In July 2009, the BCBS introduced some enhancements to the Basel II framework and issued a Basel III package that is being implemented in stages since January 2013.

Basel II creates an international standard that regulators can use to set up a regulatory framework for different types of risk, including operational risk. The ultimate aim is to create consistency among national regulations globally to limit the risks to both banks and the national economies to which healthy banks are incredibly important. Hong Kong adopted the Basel II standards in January 2007.

As previously discussed, Basel uses a “three pillars” concept to tackle risk. The first pillar deals with minimum capital requirements to address risk. The second focuses on supervisory review. The third tackles the thorny issue of market discipline.

Pillars I, II, and III

Pillar I of the Basel Capital Accord approach to operational risk addresses the issue of calculating the operational risk capital charge. Pillar II deals with the supervisory review of capital adequacy of banks, of which the operating risk capital charge is an important element. For its part, Pillar III deals with market discipline and public disclosure, which are also important aspects of operational risk management.

Regulatory Capital Charge

Pillar I considers the minimum risk-based capital requirements for banks and financial institutions. It requires every bank to compute the capital charge for operational risk independently. Under this approach, banks are required to set aside capital above the minimum required amount, which is known as the floor capital.

There are three tiers of regulatory capital. Tier I includes paid-up share capital and common stocks as well as disclosed capital reserves. Tier II considers undisclosed reserves, asset revaluation reserves, general provisions and general loan loss reserves, hybrid capital instruments, and subordinated debt. Tier III, which is not always applicable, includes subordinated capital debt. The amount of Tier II capital cannot be larger than Tier I capital while Tier III capital can only be used to deal with market risk capitalization, not for operational risk management, for which there are capital charges set by regulators. It is worth noting, however, that incoming Basel III rules, which will be implemented in various jurisdictions including Hong Kong over several years starting in 2013, eliminate Tier 3 capital instruments.1

In 2001, the BIS suggested that capital charges should be enough to cover unexpected losses that result from operational risk events. This is because most banks likely to incur expected losses typically deduct them from the income they report yearly. The BIS approach, embedded in Pillar I, proposes calibrating the capital charge for operational risk on both expected and unexpected losses but it also suggests that the amount set aside for provisioning and loss deduction be deducted from the minimum capital requirement.

This has changed somewhat since 2004 when using the AMA to calculate the capital charge although not when using the BIA or the SA. The changes have emerged partly as a result of accounting rules in different countries that do not provide a clear and effective mechanism to set provisions and may not, as a result, reflect the true magnitude of expected losses. Since 2004, the Basel accord proposes estimating the capital charge by adding provisions for expected and unexpected losses and then subtracting the portion for expected losses if a bank demonstrates that it can capture those losses through internal business practices.2

Capital Adequacy and Regulatory Principles

The purpose of Pillar II is to help guide national regulators to establish policies for overseeing the capital adequacy of banks and other institutions, including the accuracy and validity of their operational risk capital charges. Pillar II posits four core principles:

- Supervisors must ensure that AIs use appropriate methodology to determine overall capital adequacy in relation to their risk profile and that they have developed a strategy to maintain capital requirements. This process includes the examination of board and senior management oversight, sound capital assessment, comprehensive assessment of risks, monitoring and reporting, and internal control review.

- Supervisors should review the banks’ internal assessment procedures and strategies, and their ability to monitor and ensure compliance with regulatory capital ratios. This includes onsite examinations or inspections, offsite review, discussions with bank management, review of work done by external auditors (provided there is adequate focus on the necessary capital issues), and regular reporting. Supervisors should take appropriate action if the bank processes are below standard.

- Supervisors should encourage institutions to hold capital above the minimum regulatory capital ratios (i.e., the “floor”). The purpose is to create a buffer against possible losses that may not have been fully covered by the regulatory capital charge (under Pillar I), and possible fluctuations in the risk exposure. Such a buffer is expected to provide a reasonable assurance that the bank’s activities are well protected.

- Supervisors must make timely interventions to prevent capital from falling below the minimum levels. Rapid remedial action should be taken if capital is not maintained or restored. Banks should have worked out the actions to be taken if the capital is insufficient, including tightening of bank monitoring, restricting dividend payments, and reviewing the capital charge assessment model.

Market Discipline and Public Disclosure

The purpose of Pillar III is to complement Pillar I (i.e., capital requirements) and Pillar II (i.e., supervisory review of capital adequacy) by encouraging market discipline through public disclosure mechanisms. These requirements would allow external players including market investors and the general public to take part in the assessment of banking performance: capital, risk exposures, capital adequacy, risk assessment and management practices.

Disclosure requirements for operational risk consist of qualitative and quantitative disclosures. Under the former, a bank is required to describe its risk-management strategies, structure and organisation of the relevant risk management function, scope and nature of risk reporting and/or measurement systems, policies for risk mitigation and hedging, and capital-charge assessment approach. For quantitative disclosures, the bank is required to disclose its capital charge for operational risk calculated in accordance with the approach it uses to calculate its operational risk.

Basel III

Still in development through 2012, implementation of the third iteration of the Basel accords—Basel III—started in 2013. Several jurisdictions from Europe to Japan, Singapore, Australia, and Mainland China have published rules to implement Basel III. The adoption of the new standard is being done in phases and would take about half a decade. Hong Kong, where regulators have been deeply involved in the development of the new standard, is also adopting Basel III in the same time frame.

The aim of Basel III is to further strengthen global capital and liquidity rules “with the goal of promoting a more resilient banking sector.” The reform package included in Basel III takes into consideration the many lessons learned during the global financial crisis that started in 2007 and aims to improve risk management and governance while strengthening transparency and disclosure. The main thrust of Basel III is to set appropriate levels of liquidity for banks and create assurances of solvency though bank-level regulation, “which will help raise the resilience of individual banking institutions to periods of stress” and address system-wide risk.3

Earlier versions of the Basel accords had sought to address these risks but their efforts were not enough, as the economic and financial crisis that started in North America in 2007 and spread to the banking sectors of dozens of countries amply showed. The global banking systems were simply “not able to absorb the resulting systemic trading and credit losses nor could it cope with the reintermediation of large off-balance sheet exposures that had built up in the shadow banking system.” The result was a widespread loss of confidence in the ability of the banking sector to deal with the crisis. Had it not been for public sector intervention through capital injections, support, and guarantees, many more institutions would have faced bankruptcy.4

As was the case with the earlier Basel accords, the BCBS developed Basel III. This time around, however, the focus was narrower. While earlier Basel accords provided for a regulatory framework for the entire banking industry, Basel III builds on that foundation to strengthen regulation, supervision, and risk management. As the BCBS notes, the main goal of the reforms introduced through Basel III is to create a stronger banking sector that is better positioned to absorb shocks from financial or economic stress, improve risk management and governance, and strengthen transparency and disclosure. Although it is hard to argue with these goals, the challenge for banks lays not in the philosophy but in the details of the new standards. It is through the details that the BCBS targeted bank-level or microprudential regulation, to make individual institutions more resilient while also creating a macroprudential or systemic regulatory structure that can deal with the cyclical challenges that banks face. In other words, it is reactive to the economic cycles that can put the capital bases of banks at risk.5

These developments have a direct bearing on the operational risk management frameworks at individual banks. Most of the reforms focus on capital adequacy ratios for various banking operations. It will often be up to the operational risk management function to ensure compliance with the new, and higher, minimum liquidity standards that Basel III sets for different banking activities.

Evolving Framework

Basel III builds on the three pillars that support the Basel II framework but the reforms introduced in early 2013 and anticipated through 2018 raise the quality and quantity of the capital base expected of banks that seeks to limit leverage to supportable levels. At the same time, through Basel III, the BCBS aims to limit the potential for contagion of a crisis by ensuring that each bank is strong enough to weather any future financial storms. In an effort to enhance risk coverage, Basel III introduces five broad sets of reforms:

- A requirement that banks determine capital needs for counterparty credit risk “using stressed inputs,” an approach similar to the one used for market risk.

- A capital charge for mark-to-market losses linked to deteriorations in the credit worthiness of a client.

- Stronger standards to manage collateral and margining periods, particularly for banks with large and illiquid derivative exposures.

- Strong standards for financial market infrastructure to address systemic risk caused by the interconnectedness of banks and other financial institutions.

- More stringent credit risk management standards.6

Basel III will strengthen regulations while making less capital available to institutions through stricter definitions and higher capital adequacy requirements. Banks and other financial institutions will be expected to set aside more capital to protect both themselves and the financial system in which they operate from any future crisis. The details of the new regulatory requirements put forth in Basel III raise capital and liquidity ratios. Basel III builds on Basel II, which was introduced in 2004 and implemented from the end of 2006 onwards and captured operational risk. Basel 2.5, agreed upon in July 2009, enhanced risk measurements related to securitisation and trading book exposures and was to be implemented by the end of 2011. Basel III sets higher capital requirements and introduces a new global liquidity framework to be implemented in stages from January 2013. Basel III raises minimum capital requirements for banks from those outlined in Basel I and Basel II. For example, Basel III requires banks to hold 4.5% in common equity, up from 2% under Basel II, and 6% of Tier 1 capital of risk-weighted assets, up from 4% in Basel II. Basel III also introduces new capital buffers such as a mandatory capital conservation buffer of 2.5% and a discretionary countercyclical buffer that allows regulators to call for another 2.5% of capital at times of high credit growth.

For risk managers the new requirements are significant. Banks are required to comply with the new requirements if (or when) they are adopted. As of the end of 2012, discussions were ongoing. European institutions, hard hit by a series of defaults by banks and sovereigns, were eager to implement the new standards as soon as possible. The U.S., a linchpin in matters of international regulation, was less eager.

With Basel III in the early stages of implementation, operational risk management is increasingly important, particularly as the amount of regulation impacting banks with international operations grows. A case in point was the lawsuit filed by the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) against Royal Bank of Canada (RBC). The commission accused RBC of making trades that violated rules on competitive pricing and arms-length transactions in the U.S. The bank claimed that the CFTC had earlier approved the trades but then changed its decision. Observers worried the lawsuit was indicative of the risk associated with more complex regulations. Although the rules aim to reduce systemic risk, as the Financial Times noted in April 2012, the details create challenges for banks that now have to “consider the risks and expense emanating from the ‘middle office’ where risk analysis and control takes place.”7

The operational impact of the new Basel III standards would likely affect four areas in particular, according to consultants and accountants PricewaterhouseCoopers. The first is process and procedures needed to meet the new functional requirements. The second is a need to create new reporting and disclosure systems that allow for the implementation of the new controls and processes under Basel III. Third is a potential opportunity to rationalize reports and disclosure procedures. Fourth is training, as staff and senior managers are required to be familiar with more complex regulations.

Basel III and the HKMA

The HKMA is a member of the BCBS and the regulator in one of the most open and interconnected banking markets in the world. In October 2012, the HKMA announced it would start implementing Basel III, in stages, from January 2013, following the BCBS timetable.8 The implementation of the new rules, which started in January 2013, would take five years through to December 2018. Local Hong Kong banks had a total capital adequacy of 15.8% on average as of December 2011, almost twice the requirement under Basel III. They also had an average of 12.4% of Tier 1 capital, double the Basel III requirements.9

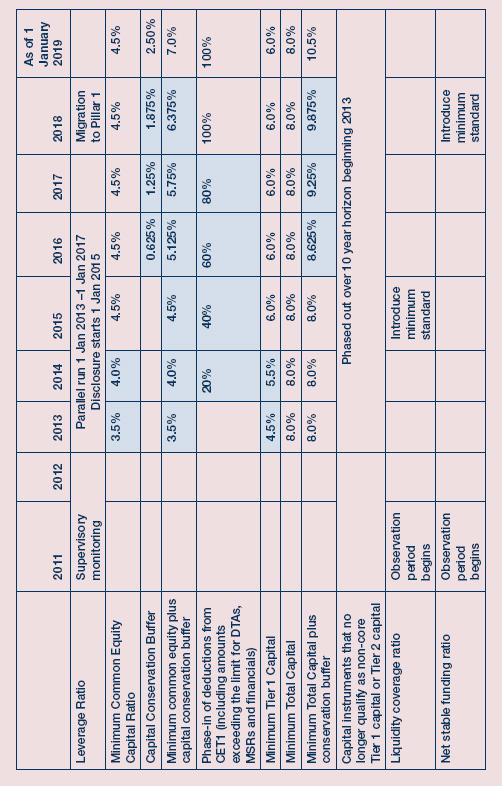

The timetable put forth by the BCBS would see steady implementation of requirements between 2013 and 2018, with most of the requirements included in the new standard to be in place by 1 January 2019. (Non-eligible capital instruments may be subject to a 10-year transitional arrangement.) For example, the minimum common equity capital ratio would be raised to 3.5% by 2013, 4% by 2014, and 4.5% by 2015. The minimum standard for liquidity coverage ratio would be introduced by 2015 and the net stable funding ratio by 2018. (See Exhibit 10.1).

EXHIBIT 10.1 Phase-in arrangements for Basel III (Bolded indicates transition periods - all dates are as of 1 January)

Annex 4: Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011. Pg 77

HKMA Risk-Based Supervisory Approach

The HKMA directs authorised institutions to strike an appropriate balance between the level of risk they are willing to take and the level of return they aim to get. The HKMA requires every AI to put in place an effective risk management system that matches the size and complexity of its operations and ensures that the risks to which it is exposed is managed well. It identifies eight inherent risks to be assessed during this process: credit risk, market risk, interest rate risk, liquidity risk, legal risk, reputational risk, strategic risk and, of course, operational risk.

The HKMA’s risk-based supervisory approach to making sure AI’s are properly managing risks, including operational risk, emphasises effective planning and examiner judgement. Examinations are customised to suit the size and activities of AIs and to focus examiner resources on areas that expose the AI being examined to the greatest degree of risk.10

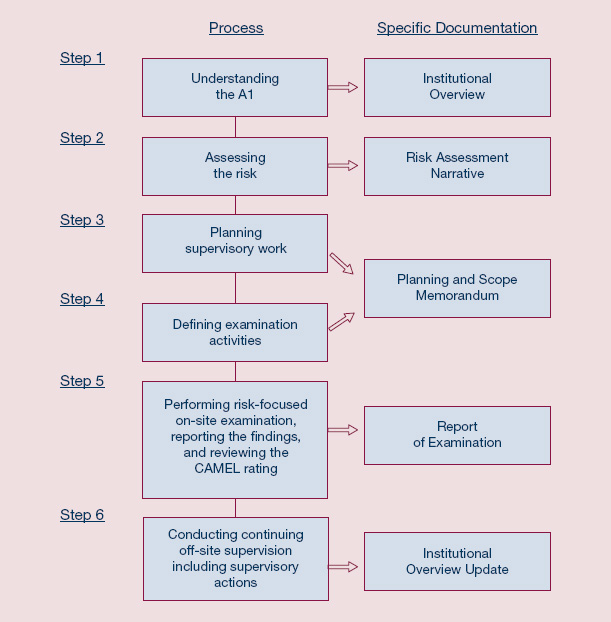

Exhibit 10.2 shows the risk-based methodology the HKMA follows in undertaking the risk-based supervisory approach. It consists of six steps, each of which requires the preparation of specific documentation on the part of the bank examiner.

In evaluating an institution’s exposure to and management of operational risk, the HKMA considers many factors, including the following:

- Appropriateness of the AI’s operational risk management framework, including the level of oversight exercised by the board of directors and senior management, and its risk culture;

- Adequacy of strategies, policies, and procedures to manage operational risk, including the definition of operational risk;

- Adequacy and effectiveness of the operational risk management processes in identifying, assessing, monitoring, and controlling operational risks;

- Effectiveness of the AI’s operational risk mitigation efforts;

- Adequacy and results of the AI’s internal review and audit of operational risk;

- The AI’s procedures for the timely and effective resolution of operational risk events and vulnerabilities; and

- Quality and comprehensiveness of the AI’s disaster recovery and business continuity plans.

Operational Risk Capital Charge

The current framework of the HKMA for locally incorporated authorised institutions lists three approaches to the calculation of the operational risk capital charge (which is then multiplied by a factor of 12.5 to estimate the risk weighted amount for operational risk). These are the basic indicator approach (BIA), which is designated the default approach, the standardised (operational risk) approach (STO), and the alternative standardised approach (ASA).11 All three approaches use gross income as a broad indicator for the scale of an institution’s operational risk exposure.12 Details of the approaches are outlined below:

- Basic Indicator Approach. Authorised institutions take their annual gross income for each of the last three years and multiply each number by a fixed capital charge factor of 15% to obtain an annual capital charge for each of these three years. The average of these three annual capital charges can be taken as the institution’s operational risk capital charge.

- Standardised (Operational Risk) Approach. Institutions divide their activities into eight business lines, as shown in Exhibit 10.2. They then calculate a capital charge for each business line for each of the last three years by multiplying the annual gross income for each business with the capital charge factor (ranging from 12% to 18%) assigned to it. The HKMA’s prior approval is needed to use STO instead of the default BIA.

- Alternative standardised approach. The ASA aims to provide a more risk-sensitive calculation of operational risk for authorised institutions with main activities that are related to retail and commercial banking. ASA is broadly the same as STO, except for the way capital charges for retail banking and commercial banking are calculated. The average amounts for loans and advances over the last three years, multiplied by a factor of 0.035, replace gross income as the indicator of exposure to operational risk. As with STO, the use of ASA instead of BIA requires the prior approval of the HKMA.

Approaches to Assessment

The first two of the three approaches to calculate operational risk capital charges considered by the BCBS—BIA and SA—and often called top-down as the capital charge is allocated based on a fixed proportion of income. AMA, the third approach, is termed bottom-up because the capital charge is estimated from actual internal loss data.

A bank can choose which approach to use, depending on its operational risk exposure and management practices, and is subject to certain requirements. Internationally active banks with diverse business activities typically adopt the advanced measurement approach, while smaller domestic banks generally implement the basic indicator or standardised approaches. Once a bank adopts a more advanced approach, it is not generally permitted to revert to a simpler approach unless it can persuade the national regulator it has valid reasons to do so.

Basic Indicator Approach

The basic indicator approach (BIA) is the simplest approach. Under it, gross income is viewed as proxy for the scale of operational risk exposure of the bank. (Gross income is defined by the Basel Committee as net interest income plus net non-interest income.) The operational risk capital charge is calculated as a fixed percentage of the average over the previous three years of positive annual gross income.

The total capital charge can be expressed as:

![]()

where

GI = gross income

n = the number of the previous three years for which GI is positive

α = the fixed percentage of positive GI

The fixed percentage of positive gross income, represented as α, is currently set by the Basel II at 15% and is supposed to reflect the industry-wide level of minimum required regulatory capital to the industry-wide level of the indicator.

The basic indicator is easy to implement and does not require expending time and effort to develop sophisticated models. It is useful at the primary stage of Basel II implementation, when loss data may still be insufficient. However, the basic indicator approach does not capture the specifics of the bank’s operational risk exposure and control, business activities structure, credit rating, and other indicators. It also tends to overestimate the amount needed to cover operational risk.

Standardised Approach

There are two sub-approaches to the standardised approach (SA): the general standardised approach and the alternative standardised approach.

General Standardised Approach

In the general standardised approach, a bank’s activities are divided into eight business lines. Within each line, gross income (GI) is a broad indicator that serves as a proxy for the scale of business operations and operational risk exposure.

The capital charge for each business line is calculated by multiplying GI by a factor, denoted by β, assigned to that business line. β serves as a proxy for the industry-wide relationship between the operational risk loss experience and the aggregate level of GI for a given business line. The total capital charge is calculated as the three-year average of the maximum of the simple summation of the regulatory capital charges across each business line and of zero.

The total capital charge can be expressed as

![]()

where β is a fixed percentage set by the Basel Committee, relating the level of required capital to the level of the GI for each of the eight business lines. The values of β are presented in Exhibit 10.3.

EXHIBIT 10.3 Beta factors under the general standardised approach

Anna S. Chernobai, Svetlozar T. Rachev, Frank J. Fabozzi, Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007), 43.

| Business Line | β | |

| 1. | Corporate finance | 18% |

| 2. | Trading and sales | 18% |

| 3. | Retail banking | 12% |

| 4. | Commercial banking | 15% |

| 5. | Payment and settlement | 18% |

| 6. | Agency services | 15% |

| 7. | Asset management | 12% |

| 8. | Retail brokerage | 12% |

Alternative Standardised Approach

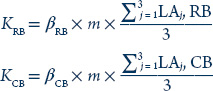

In the alternative standardised approach, the operational risk capital charge for the retail banking (RB) and commercial banking (CB) business lines is calculated by taking total loans and advances as the operational risk exposure indicator, instead of gross income. The β factor is further multiplied by a scaling factor denoted by m, which is set as equal to 0.035.

For these two business lines, the capital charge amounts are calculated as follows:

Like BIA, the standard approach is easy to implement. In addition, the estimates may be said to offer greater accuracy because differences in the degrees of operational risk exposure by business lines are taken into account. However, in taking a fixed fraction of a business line’s gross income, SA does not take into account specific characteristics of this business line for a particular bank. It also implies perfect correlation between different business lines, which is not always the case. As such, SA may result in an overestimate of the true amount of capital required to capitalise operational risk, like BIA.

To qualify for the standardised and alternative standardised approaches, a bank must be able to map its business activities to its business lines. It must be actively involved in monitoring and controlling the bank’s operational risk profile and its changes. This includes, for example, regular reporting of operational risk exposures, internal and/or external auditing, and valid operational risk self-assessment routines and supervision.

Advanced Measurement Approach

With the advanced measurement approaches (AMA), a bank may use its own method to assess its exposure to operational risk, as long as the national regulator agrees that it is sufficiently comprehensive and systematic. The bank must demonstrate that its operational risk measure is evaluated for a one-year holding period and has a high confidence level (such as 99.9%).

The resulting capital charge is directly derived from the bank’s internal loss data history and should capture, in theory, the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the bank’s risk measurement system. The bank may use external data (appropriately rescaled) to supplement its internal data, and utilise statistical techniques such as factor analysis and Bayesian methods, among others.

Three sub-approaches have been developed under AMA: internal measurement approach (IMA), scorecard approach (ScA), and loss distribution approach (LDA).13

Internal Measurement Approach (IMA)

In the internal measurement approach (IMA), the bank’s activities are classified into a matrix of business lines/event type combinations. The actual number of business lines and event types depends on the complexity of the bank’s structure. Assuming that a bank has eight business lines and seven event types, the pairing will result in a 56-cell matrix.

The operational risk capital charge is determined by the product of three parameters: the exposure indicator (EI) such as gross income; probability of event (PE); and loss given the event (LGE). The formula EI × PE × LGE is used to calculate the expected loss (EL) for each business line/loss type combination (i.e, each cell in the matrix). The EL is then rescaled to account for the unexpected losses using a parameter γ, which is different for each business line/loss type combination, but predetermined by the bank’s supervisor.

The total one-year regulatory capital charge is calculated as:

![]()

The main drawbacks of IMA are its assumptions that there is perfect correlation between the business line/loss type combinations and that there is a linear relationship between the expected and unexpected losses.

Scorecard Approach (ScA)

In the highly qualitative scorecard approach (ScA), a bank determines an initial level of operational risk capital (based on the BIA or SA methods, for example) at the business line level, and then modifies these amounts over time on the basis of scorecards. The ScA is forward-looking, as it aims to reflect improvements in the risk-control environment that would reduce both the frequency and severity of future operational risk losses.

The scorecards usually rely on such indicators as proxies for risk types within business units. Line personnel complete the scorecards at regular intervals, say annually, and these are reviewed by a central risk function.

The one-year capital charge (KScA) can be computed as:

![]()

where R is some risk score that rescales the initial capital charge K into the new one for a given business line.

Loss Distribution Approach (LDA)

The loss distribution approach (LDA) makes use of the exact operational loss frequency and severity distributions of the bank. It uses an actuarial type of model for the assessment of operational risk. Like IMA, LDA classifies a bank’s activities into a matrix of business lines/event type combinations. For each pair, the key task is to estimate the loss severity and loss frequency distributions. Based on these two estimated distributions, the bank then computes the probability distribution function of the cumulative operational loss.

The operational risk capital charge is computed as the simple sum of the one-year value-at-risk (VaR)14 measure (with confidence level such as 99.9%) for each business line/risk type pair. The 99.9th percentile means that the capital charge is sufficient to cover losses in all but the worst 0.1% of adverse operational risk events. That is, there is a 0.1% chance that the bank will be unable to cover adverse operational losses.

For the general case (eight business lines and seven loss-event types), the operational risk capital charge can be expressed as:

![]()

LDA differs from IMA in two important ways. First, LDA aims to assess unexpected losses directly, not via an assumption about the linear relationship between expected loss and unexpected loss as in IMA. Second, the bank supervisor does not need to determine a multiplication factor γ.

Unlike IMA and BIA, LDA can potentially provide an accurate operating risk capital charge, particularly if it adjusts for correlation effects and other factors. (The simple summing up of VaR measures implies perfect correlation among the business line/event type combinations, which is seldom the case.) However, loss distributions are complicated to estimate and can create model risk—that is, misspecification of the model can produce wrong estimates.

In LDA, extensive internal data sets (at least five years) are required, which not all banks have. This approach also lacks a forward-looking component because the risk assessment is based only on past loss history. If the national regulator does not specifically set the VaR confidence level (the Basel Committee says only that it should be “high”), banks may be tempted to use a slightly lower level (from 99.9%, for example), to lower their operating risk capital charge. Even a slight change in the VaR confidence level can lead to significantly different results.

Basel III Risk Exposures

While the main thrust of Basel III is to raise the quality and level of the capital base of banks around the world, the new capital framework also seeks to tackle material risks to the solvency of banking institutions. To do this, Basel III seeks to make banking institutions more reliant on their own risk control frameworks and less reliant on external data, such as credit ratings. It is already well established that risk control does not operate in a silo-like fashion but is rather an interactive proposition. Credit risk is not independent from liquidity risk and operational risk easily covers most other areas. It is therefore important for operational risk managers—and other risk management functions—to understand the new requirements under Basel III and work within their institutions to develop an operational risk management framework that takes these exposures into account.

The Basel III framework considers risk coverage in depth. A document revised in June 2011 titled “Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems” outlines this overall framework. Section II focuses on risk coverage and looks in depth at counterparty risk and the dangers of relying on external agencies such as rating agencies for risk management.

Counterparty Risk

A major driver of the financial crisis of 2007 was a failure among banks and other financial institutions to “capture major on- and off-balance sheet risks, as well as derivative related exposures.”15 To better deal with these risks, Basel III introduced a series of reforms. The first is a series of reforms to existing regulation to ensure banks manage counterparty credit risk, valuation adjustments, and wrong-way risks. The reforms in this area include16:

- Basel III introduces a requirement that banks use a single and consistent stress calibration model to determine the default risk capital charge for counterparty credit risk. This calculation should be based on either the portfolio-level capital charge based on effective expected positive exposure (EPE) and the portfolio-level capital charge based on effective EPE using a stress calibration for the “whole portfolio of counterparties.”

- Basel III also introduces an asset value correlation multiplier for large financial institutions and provides a revised calculation method for this multiplier. A multiplier of 1.25 now applies to all financial institutions with assets of at least US$100 billion. This includes insurance companies, brokers, dealers, banks, thrifts, and futures commission merchants as well as unregulated financial institutions of all sizes.

- The new requirements also increase the margin period of risk. Basel III introduces a “supervisory floor” of five business days to net sets of repo-style transactions subject to daily re-margining and mark-to-market valuation. It sets a floor of 20 business days for netting sets of trades involving illiquid collateral or over-the-counter derivatives that cannot be easily replaced. It is also up to banks to consider the concentration of the trades or securities it holds and whether they are too concentrated on a single counter-party. This includes taking into account the potential of that counterparty suddenly exiting the market.

- There are also new rules to deal with Central Counter Parties (CCP) and a new regulatory capital treatment for exposure to CCPs.

- Basel III also introduces stricter requirements for stress tests that banks should perform for counterparty risks. Stress testing should include a number of new elements that consider the entirety of a counterparty trade, ongoing (monthly) reports on exposure stress testing of principal market risk factors, multifactor stress testing scenarios, quarterly stress tests addressing severe economic or market events and stressed conditions, and exposure stress tests and their integration into regular reporting to senior management, tests for the severity of factor shocks that is consistent with the purpose of the stress test, possibly introducing reverse stress tests and the integration of stress testing into the risk management framework and risk culture.

Few of these requirements are completely new but they are significantly higher than in the past. More significantly, however, Basel III seeks to embed a whole series of operational risk management practices into the regular practices of banks and to shift the culture within banking institutions to a broader recognition of the importance of careful and stringent risk control and management.

External Agencies

The new Basel III requirements also pay considerable attention to the dangers that banking institutions face when dealing with external agencies and carefully consider which claims are rated and which are not. In particular, it is important for banks to not extend a high rating to one issue of a particular institution (which may also be rated highly) to another issue that is not rated. In other words, if a particular issue has not been rated it should be treated as such and not as an extension of other high ratings that the same group may hold. At the same time, banks should also have their own internal methodologies to assess credit risk, regardless of whether a borrower is rated by a third party. Among the more sophisticated banks, the credit review process should cover risk rating systems, portfolio analysis and aggregation, securitization and complex derivatives, and large exposures and risk concentrations.

Meanwhile, it is up to national supervisors to determine “on a continuous basis” whether external credit assessment institutions (ECAI) meet a set of eligibility criteria that includes objectivity, independence, international access and transparency, disclosure, resources, and credibility. External agencies such as sovereign entities, banks, and securities firms may also act as guarantors and Basel III deals with these activities as well. In broad strokes, guarantors should have a higher credit rating than the entity they are guaranteeing. At the same time, banks should be consistent in the use of external agencies and “will not be allowed to ‘cherry-pick’ the assessments provided by different ECAIs and to arbitrarily change the use of ECAIs.”18

Summary

- The Basel Committee for Banking Supervision of the Bank for International Settlements introduced the Basel II accords in 2004 and enhanced them in 2009. A third set of accords, known as Basel III, will be implemented in stages from 2013.

- Basel II uses a three pillar approach to the development of regulatory standards.

- Pillar I considers the approach regulators should use to set risk-based capital requirements for banks and other financial institutions and outlines three tiers for capital requirements, with Tier I taking into consideration paid-up share capital, common stock, and disclosed capital reserves. Tier II considers undisclosed reserves, asset revaluation reserves, hybrid capital instruments, and subordinated debt. Tier III includes subordinated capital debt and is not always applicable.

- Pillar II aims to help national regulators set policies to oversee the capital adequacy ratio of banks and other institutions and outlines the supervisory approach to risk management.

- Pillar III, the shortest, considers the importance of market discipline and public disclosure in the management of operational risk.

- The HKMA requires AIs to balance out the level of risk they are willing to take against the returns they expect. It also identifies eight inherent risks to be assessed: credit risk, market risk, interest rate risk, liquidity risk, legal risk, reputational risk, strategic risk, and operational risk. The HKMA’s risk-based supervisory approach emphasizes effective planning and examiner judgment.

- To calculate the capital charge for Hong Kong banks, the HKMA considers the basic indicator approach and the standardized approach. The HKMA does not yet recommend the use of the advanced measurement approach (AMA).

- The basic indicator approach is the simplest. It considers gross income as a proxy for the scale of the operational risk exposure of a bank and the risk capital charge is calculated as a fixed percentage of the average over the previous three years.

- There are two options for the standardized approach—the general standardized approach and the alternative standardized approach. The former divides the activities of a bank into eight business lines. The latter calculates operational risk capital charges for retail and commercial banking business lines by taking total loans and advances as the operational risk exposure indicator rather than gross income.

- Under the advanced measurement approaches, of which there are three, banks may use their own methods to assess exposure to operational risk as long as the regulator agrees the approach is comprehensive and systematic. The three possible advanced measurement approaches are the internal measurement approach (IMA), the scorecard approach (ScA), and the loss distribution approach (LDA).

Key Terms

Study Guide

Further Reading

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011. Pg 38.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011. Pg 38.

Chernobai, Anna S.; Rachev, Svetlozar T.; Fabozzi, Frank J., Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2007. Print.

Hong Kong Monetary Authority; Supervisory Policy Manual: Operational Risk Management; November 2005.

1 In Paragraph 9 of Basel III: A Global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems, the BCBS notes: “Tier 2 capital instruments will be harmonized and so-called Tier 3 capital instruments, which were only available to cover market risks, eliminated.”

2 Chernobai, Anna S.; Rachev, Svetlozar T.; Fabozzi, Frank J., Operational Risk: A Guide to Basel II Capital Requirements, Models, and Analysis. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Ltd, 2007. Print.

3 Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011.

4 Ibid, pg 1.

5 International regulatory framework for banks (Basel III); accessed online at www.bis.org/bcbs/basel3.htm.

6 Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011.

7 Tellis Demos; “Financial reforms: Regulators aim to make ‘middle office’ a safer place”; Financial Times; 13 April 2012.

8 Implementation of Basel III in Hong Kong, HKMA, accessed at http://www.hkma.gov.hk/eng/key-functions/banking-stability/basel-3.shtml.

9 These levels of capital adequacy do not take into account countercyclical capital buffers and systematically important financial institution (SIFI) surcharges suggested in Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems revised in June 2011 and Global systemically important banks, assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement issued in November 2011.

10 Risk-based supervision provides useful input for HKMA’s banking supervision teams that carry out Pillar II reviews on AIs. The HKMA uses ongoing risk-based supervision to form a view of an AI’s overall risk profile. The risk profile is a key component of the Supervisory Review Process done by the HKMA on each individual AI. This review process is part of the HKMA’s implementation of Pillar 2 of Basel II.

11 See Section 7.6 of “CA-G-1: Overview of Capital Adequacy Regime for Locally Incorporated Authorized Institutions” in the HKMA’s Supervisory Policy Manual.

12 Except for retail banking and commercial banking under ASA, which use the total outstanding loans and advances as the exposure indicator.

13 Under the Basel Committee’s latest regulatory capital guidelines, banks are allowed to work out their own alternative AMA model, sufficiently supported by back-testing, that they judge best reflect their required operational risk capital. We discuss these three sub-approaches in this book in the interest of comprehensiveness and under the assumption that the alternative AMA model a bank develops will use the basic principles of these sub-approaches.

14 Value-at-risk determines the worst possible loss that may occur at a given confidence level and for a given time frame. Used for a number of years in the measurement of market risk and credit risk in internal risk models, VaR has now been extended to the calculation of operational risk capital charge in the loss distribution approach.

15 Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011.

16 For greater detail see “Section II: Risk Coverage” of Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011.

17 Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011. Pg 38.

18 Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Bank for International Settlements; Revised June 2011. pg 53.