Chapter 3

Anxiety Disorders: How to Calm the Anxiety Cycle and Build Self-Confidence

Abstract

Many children experience anxiety at different times in the course of their development. They may be anxious about whether they will fit in with peers, an upcoming school presentation, or why they got a bad grade on a homework assignment. A little anxiety can serve as a protective mechanism in helping the child be vigilant to stressful or chaotic situations. It also helps motivate the child to prepare for difficult or challenging situations, especially those involving performance expectations. This chapter will focus on more extreme forms of anxiety that negatively affect the child’s ability to function and derail the sense of self.

Keywords

anxiety

ADHD

neurobiological mechanisms

PTSD

Many children experience anxiety at different times in the course of their development. They may be anxious about whether they will fit in with peers, an upcoming school presentation, or why they got a bad grade on a homework assignment. A little anxiety can serve as a protective mechanism in helping the child be vigilant to stressful or chaotic situations. It also helps motivate the child to prepare for difficult or challenging situations, especially those involving performance expectations. This chapter will focus on more extreme forms of anxiety that negatively affect the child’s ability to function and derail the sense of self.

When anxiety floods a child, it becomes consuming and things that might be effortless for others become overwhelming. Simple tasks such as getting out the door to go to school, calling a friend for a playdate, or getting started on homework may be so overwhelming that the child is incapable of getting started. Ricky was such a child who suffered from both ADHD and anxiety. Just the thought of such everyday tasks would set him into a frantic state of activity to avoid the tasks that he was supposed to be doing. He did things like skate boarding in the house, bouncing a basketball against the living room walls, or running up and down the stairs nonstop, which not only resulted in him delaying the task he needed to do, but his mother would end up yelling at him to stop. It was a constant battle to get Ricky to do everyday tasks. Then at night, Ricky could only fall asleep if he held his mother’s hand and would frequently awaken in the night from nightmares that he and his family were being attacked by terrorists or that he was kidnapped.

Some children become immobilized over performance expectations and spend an inordinate amount of time laboring over a task that should have taken only a short time. Other children cannot stand to be alone and become anxious, feeling abandoned or worried that something bad will happen to them. In sharp contrast to Ricky, Cody was a 12-year-old boy who became frozen with fear at the thought of going to school. Despite the fact that he was a very good student with no learning problems and a long history of academic excellence, he dreaded the idea of facing school each day. Cody was a large, sturdy boy who was very effective at blocking his mother’s passage in the hallway before school. She couldn’t get past him to fix breakfast or to drive him to school. Oftentimes Cody moans in a low guttural sound as if he were in great pain as he barricaded the corridor. When asked to describe his anxiety in words, all Cody could do was freeze up and say, “I just don’t know.”

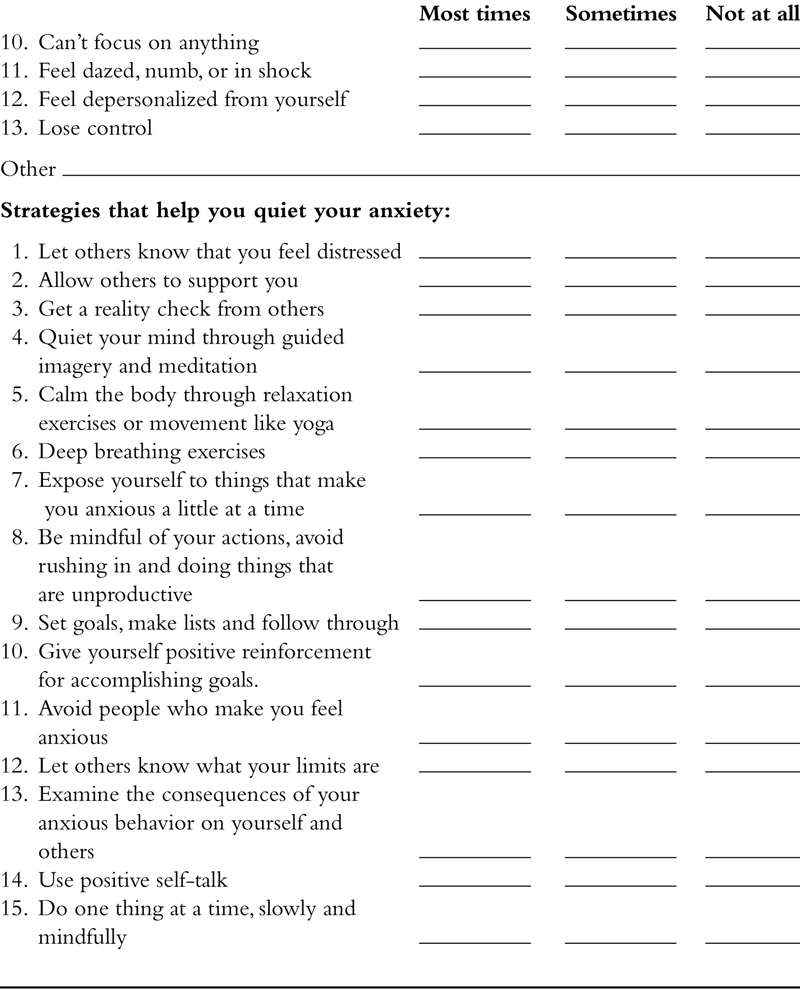

In this chapter, the neurobiology of anxiety disorders will be reviewed. The different causes of anxiety in children will be described emphasizing constitutional and relational factors as well as environmental stressors or traumatic events that can agitate children. Irrational fears and phobias will be discussed. Case examples will be depicted that include children who have been anxious since early childhood, reflecting a biological vulnerability to anxiety as well as children subjected to trauma. Strategies to calm anxieties will be described focusing on mind–body and cognitive-behavioral techniques. Finally, a checklist is presented for use in helping to identify the sources of anxiety in children, the way in which it manifests itself, and strategies that they have found useful.

1. Symptoms of anxiety

There are a number of different ways that anxiety can manifest. In many cases, the anxiety disorder relates to an anticipatory stance that something bad is about to happen or that the child will lose control. In many individuals with anxiety, it is accompanied by depression (McNally, 1994; Rynn & Brawman-Mintzer, 2004). It is common for individuals with anxiety to have difficulty with social situations, especially when they feel forced to interact with unfamiliar people or when they feel they might be judged or scrutinized by others. When there is social anxiety, the child often manages it by avoiding social situations, thus removing the source of their problem.

In other individuals, anxiety centers around worries about safety in certain environments that can impact their ability to go places, their need to lock things up, or a sense of doom when in enclosed spaces like an airplane or elevator. Typically the child experiences fear that a panic response will happen if they feel anxious. They dread the autonomic responses that accompany the anxiety—the pounding heart, the feeling of doom or suffocation, or overwhelming nausea. In panic disorder, what is happening is a failure of signal anxiety when presented with a danger. There is no readying response to alert the child and instead, the child experiences overwhelming flooding anxiety (Alexander, Feigelson, & Gorman, 2005).

A very common and debilitating form of anxiety is obsessive–compulsive disorder, which will be discussed in Chapter 7. In this type of anxiety, the child is overwhelmed by unwanted, negative thoughts that are stuck in his mind. The thoughts are often illogical but the belief is so overpowering that the child cannot function unless he performs certain rituals or avoids certain things like germs. Often the child engages in compulsive behaviors like perpetual ordering of objects to decrease the anxiety associated with the obsession.

Posttraumatic stress disorder occurs when the child has experienced a real, life-threatening event such as living in a chaotic household, being abused or neglected by family members, losing a pet or loved one, or seeing something horrible happen. Frequently the child stores sensory memories of the event so that a sight, smell, sound, temperature change, or certain type of touch can elicit the trauma all over again. Children suffering from PTSD do everything in their power to avoid and escape from situations that might cause them to reexperience the bad feelings all over again. Often the child with PTSD experiences symptoms of numbness, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Ten-year-old Lev’s mother was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. He grew up witnessing his mother’s violence and disturbing behavior including seeing her threaten his father with a knife and making constant accusations in front of Lev that his dad was cheating on her. She was often delusional and would talk in crazy ways to people or things that were not in the room. Lev was extremely fearful that he would also become schizophrenic as his mother said he would. At times Lev would feel numb or dazed when at school or sitting in his bedroom, losing track of what he was doing in the present moment. He also became very fearful that somebody was watching him outside his bedroom window, thus resulting in a sleep disturbance with terrible nightmares. His symptoms improved dramatically once his mother received residential treatment and she was removed from the home. We also worked in therapy to install a secure sense of safety, to develop good trusting relationships with adults and peers, and to learn how to cope with anxiety and stress related to the trauma he had experienced.

Finally, generalized anxiety disorder is one in which the child feels agitation and anxiety of unknown origin. The child worries constantly that negative things will happen in the future. Sometimes these anxieties have been transmitted from the child’s caregivers who might have shared similar worries, often unexplained to the developing child. In some cases, the parents have family secrets, perhaps too difficult to share with their developing child, which can induce anxiety in the child. For example, Carla was a 7-year-old child with selective mutism who would not speak to anybody outside the family. In play therapy, Carla frequently played out a story whereby my character was forced to grovel about to find food or shelter while her character had large feasts of food and lived in a mansion. When I managed to find food, it was always inedible and disgusting things like old bugs and eyeballs lying in mud. Without my or Carla’s knowledge, I learned after working with Carla for about a year that the grandparents on both sides of the family were Holocaust survivors. Carla’s parents did not feel that this was important history to share with me and they did not want their anxious daughter to learn of this family story. The parents seemed surprised when I suggested that Carla probably knew about her grandparents, but they liked my suggestion to frame their lives as stories of resilience and survival and to find ways for Carla to be more resilient in her life.

Regardless of the origin of the anxiety disorder, a commonly observed process is that the child finds that they are flooded by physiological sensations that overwhelm them. Commonly the child misinterprets or distorts the reality of the situation or hyperfocuses on certain aspects of the situation (i.e., this room is too hot and now something bad is going to happen). Negative cognitions become entrenched in the child’s psyche (i.e., I cannot control what will happen), which leads to obsessive behaviors, maladaptive responses, and/or depression or irritability.

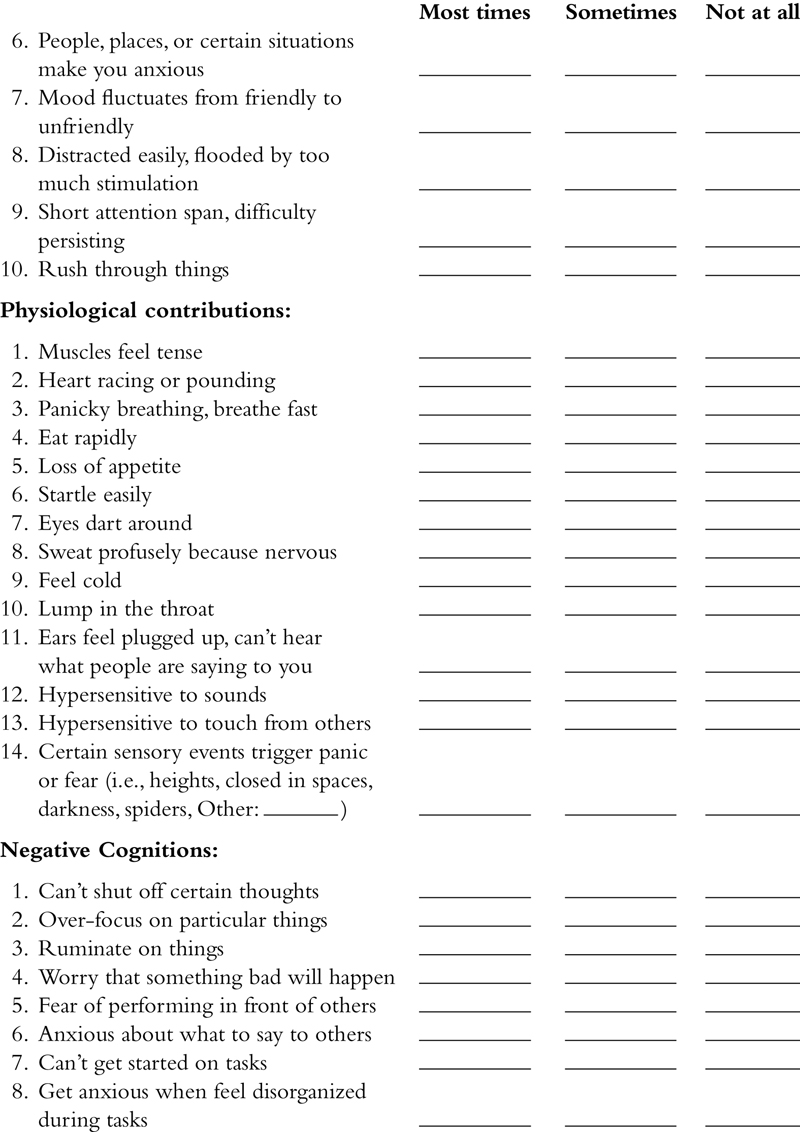

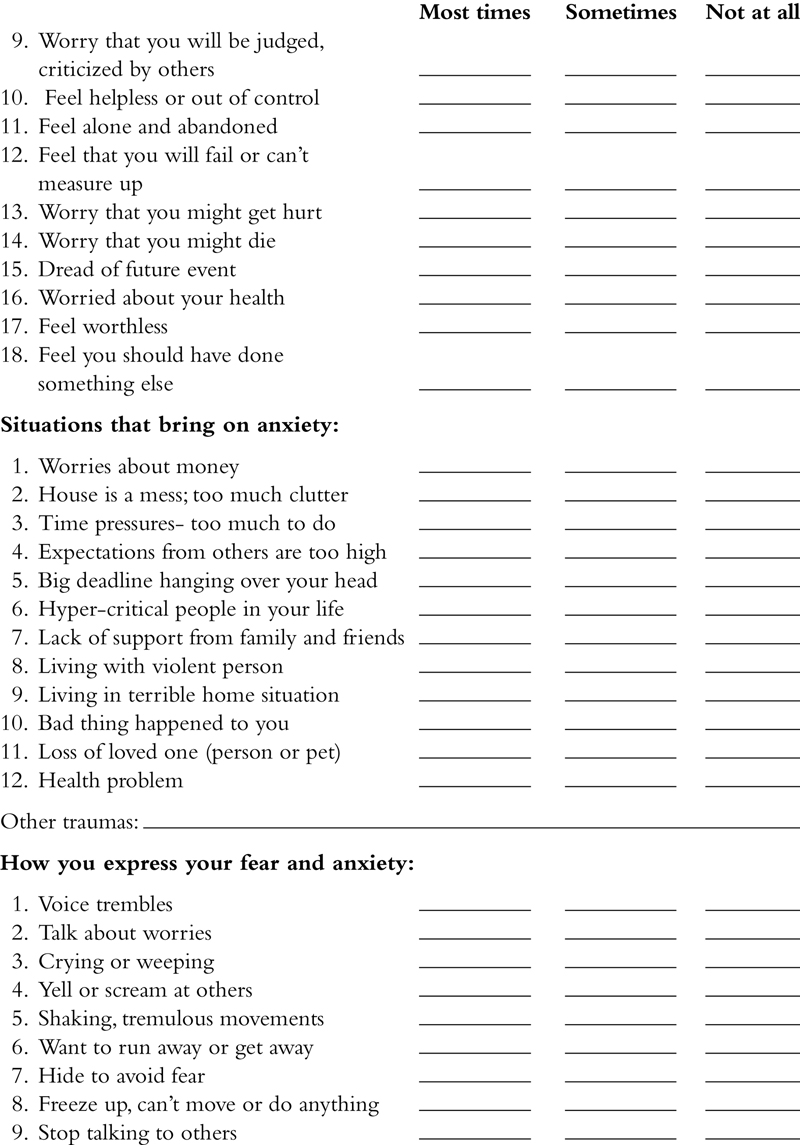

Here are some commonly observed symptoms in anxiety disorders.

2. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying anxiety

The seat of anxiety in our brain is located in the basal ganglia, specifically the amygdala. This large structure surrounded by the limbic system helps to integrate feelings, thoughts, and movements. It enables the child’s body to respond to emotions and thoughts through body responses such as trembling when nervous, jumping when startled, or freezing the body when scared. The amygdala provides the program for the fight or flight response, an important protective mechanism of the nervous system necessary for survival and biological protection. The amygdala accomplishes this by receiving sensory input of threatening stimuli from the thalamus. The amygdala relays this information to the hypothalamus to produce stilling of the body, fight, or flight responses. This is the same reaction that occurs when anxiety is elicited (LeDoux, 1996).

The amygdala helps to set the child’s anxiety level in response to stressful situations. Overactivity in the amygdala results in the child freezing or becoming immobile when stressed or overwhelmed. They may also feel nervous or tense and unable to act in an adaptable way. In contrast, the child with an underactive amygdala, also seen in children with attention deficit disorder, may react by mobilizing into action and feeling revved up. A child may fluctuate between these two states of immobility or freezing up and restless agitation. The amygdala is important in modulating motivation and in processing the experience of pleasure and excitement. The secretion of dopamine makes this possible. Many children with anxiety are fearful of trying new things. They may have little pleasure or fun in their lives because they are so riddled with worry.

Other important brain structures that impact anxiety are the cingulated system and the prefrontal cortex. The cingulated gyrus traverses longitudinally through the frontal lobes. Its function is cognitive flexibility and the ability to shift attention from one thing to another. Being able to transition from one activity to another, willingness to try new things, and the ability to engage in new social situations are some of the things that the cingulated gyrus monitors. Children who get stuck on a particular idea, as seen in obsessive–compulsive disorder, are likely to have problems with this brain structure. The cingulated system is also implicated in goal setting and future planning. When the cingulated system is compromised, the child is apt to worry, get stuck on thoughts or behaviors, and has difficulty letting things go. Overactivity of the cingulated gyrus results in a cognitive flooding effect. The child can’t shut off excessive thoughts or worries and they may overfocus on particular thoughts or details.

There is a strong autonomic component associated with anxiety. This includes pounding of the heart, heart rate variability, and rapid breathing. Poor modulation of the vagal nerve causes gross sympathetic nervous system reactions (elevated heart-rate and respiratory responses), which can produce a physical sense of urgency, a wish to escape, a feeling of dread and lack of safety along with physiological flooding. The result is the child has a complete lack of preparedness to react to the situation in rational and organized ways.

3. Types of anxiety disorders in children

In this next section, the different types of anxiety in children will be described in detail.

3.1. Social anxiety

The underpinnings of social anxiety or agoraphobia are often related to the child’s relationships from early childhood. Frequently the parents report that their child had significant difficulty separating from them early in life. The capacity for trust, security, and dependability in relationships is installed in early childhood through the parent–child relationship. This early attachment between parent and child provides the child with a sense of security that the world is a safe place and his needs will be met.

In normal development, the child learns to transfer the attachment they have with their parents to others, learning to trust people outside of the family. We think of the 9-month-old who develops stranger anxiety and clings vigorously to their parent’s side. An anxious child might report that his mother described him as a clingy child who resisted going to new places or trying new things.

Another important developmental milestone is when the child nears 2 years of age and comes to understand that his needs are separate from his parents. The child of this age asserts vigorously what he wants or needs in that very moment. As the child’s awareness of his separateness emerges, it raises the fear that if the parent leaves, he might not return. The capacity to assert oneself and develop a core sense of self is often compromised in the child with social anxiety as this early stage of development may have been affected.

In addition to how well a child negotiates these early stages of separation and individuation, the quality of the relationship that the child has had with his caregiver is very important. If the child has an anxious mother who hovers around them and is hypervigilant to their every move, the child is apt to develop an anxious attachment with his parent. Anxious-ambivalently attached children seek proximity with their caregivers, but are not easily soothed and have difficulty organizing themselves to play and explore the world. Often the child internalizes their mother’s anxiety and her lack of emotional safety, which leaves the developing child anxious and emotionally unregulated.

Another type of attachment disorder that can fuel anxiety in the developing child is an avoidant attachment. These children have mothers who are dismissive and ignore them when they seek and need reassurance and safety. The child grows up with the lack of expectation that their mother can soothe them. The child learns that they have to take care of themselves without the help of others and that whatever stress they feel, it will only be compounded by the mother’s inattention or dismissal. Some children who experience a dismissive parent tend to overfunction in the role of a parent, especially if they are an older sibling in the family.

Anxiety can also be installed by a disorganized attachment with the caregiver. The caregiver in this case is scary and scared at the same time, which leaves the child in an abandoned state with no emotional resources. The child is in a quandary of whether to approach the mother for security or to avoid her at the same time. The result is complete emotional turmoil for the child. When stressed, the child may exhibit self-injurious behavior and become chaotic and disorganized, or the child may freeze in place, unable to act in any adaptable way. This pattern of attachment can contribute to a child developing a borderline personality disorder (Cozolino, 2006).

3.1.1. Case example of social anxiety in a mother and her child

It was very difficult for William’s mother, Estelle, to come to my office for the initial intake interview for her son. She tried to negotiate a phone interview to avoid leaving her home. I insisted that she come to my office and reassured her that I would help her become comfortable in bringing her son to see me. In the beginning, Estelle was frequently late to appointments or sometimes wouldn’t show because she couldn’t manage to leave her house.

Estelle, her husband, and William all had notable appearances. Estelle had bouffant, auburn hair trained in sewer pipe curls, cherub lips, a sailor top dress, and plump hands. She reminded me of the actress, Shirley Temple, from the ‘50s. I met her husband, Roger, in one of our early sessions and was amazed to see that he, too, reminded me of a little boy. Roger worked as an accountant. William, who was 7 years old, looked like a little businessman wearing a jacket and pants and surprisingly carried his own business cards that said, “William Gilroy. Specialties: T-ball, Pokemon, and video games.” William attended a small private school near home and had never been left with a babysitter. When the parents came for a parent guidance session, they brought William along if he wasn’t in school. In those instances, I encouraged William to play in our secure waiting room, but it was too much for Estelle to bear. It was next to impossible to have a session with him in the room. He was constantly interrupting her, talking nonstop, and clearly unable to play alone.

Estelle reported that she had always had severe social anxiety. She had her groceries delivered to her home and did online shopping for everything—her son’s clothes, books, and toys and household supplies including furniture. She had few friends or family and kept a small circle of people with whom she would have any contact with. The only places she would leave the house for were her husband’s office, to take her son to school, and to a particular restaurant that they liked to go to. If her son wanted a play date with a neighbor child or classmate, it had to be at their house and it was always very brief. Estelle would refuse to leave the room, hovering over her child as if there were grave dangers lurking about. William, had few friends, was equally fearful about meeting people just like his mother, had very poor play skills, and talked incessantly.

Within a few sessions, it was apparent that both mother and child had extreme social anxieties. Estelle revealed in our early work that William slept with her and Roger at night. Estelle said, “I love watching his sweet face while he sleeps. It’s the only time that he shuts up and isn’t talking constantly.” Estelle couldn’t seem to get his bedroom quite right. It was always in a state of being redecorated with Estelle sending furniture back and ordering new things. Frankly, she liked William in their bed and felt comforted by his presence. She had infantilized William and allowed him to bottle feed until he was 5 years old.

Estelle expressed many worries about William getting lost or running off. When he was near other children, she felt that they were too aggressive and would hit him. Estelle cried as she told me this, saying that it made her feel very bad that he was getting injured and his feelings hurt. It was then that she recounted a story of her older brother who at age 2 years, ran out in front of a truck and got killed. Estelle was a baby at the time and had no memory of this event, but this early trauma clearly marked her childhood and the meaning she had for her parents. Her family never spoke about it, their grief locked in a vault. As a result, her parents hovered over her, worrying about her every move, and wouldn’t let her out of their sight. It seemed that Estelle’s social phobia was conditioned by her parents’ loss, but they too, were highly anxious and the attachment that Estelle had with her parents was laden with anxiety and fear. This helped to explain Estelle’s hypervigilance and social anxiety. Making the connection between this event in her life and the social phobia and anxiety that both mother and child felt was very helpful to understanding their dynamic. Both mother and child were caught in a cycle of deep-seated anxiety that they lived with every day.

Despite Estelle’s extreme anxiety about her child and leaving the home, she couldn’t stand it that her child followed her around constantly. She lamented, “He won’t listen! I screech at him to turn off the TV or get out of bed. I tell him to stop interrupting me when I’m on the phone. He claws at my clothing and pulls at my hair if I’m on the phone. He complains that he’s bored even though our house looks like F.A.O. Schwartz!” The only time that William was separated from his mother was to go to school. Estelle and Roger had enforced very strict rules at home. For instance, nobody could drink coffee at the table because it might spill and hurt William. These rules helped Estelle to feel more in control.

In the first year of our work together, Estelle was extremely controlling of what I could work on with William, trying to dictate what the therapy could be about. An important aspect of my work with her was to help her understand that in order for both of them to progress, she had to tolerate some separation from him and trust me to help the two of them. We tried to find more appropriate ways for her to assert control of William than to hover around him or to attempt to control his every move. Estelle had to learn to leave the room and quiet her anxiety by doing a self-distracting activity when the urge to hover rolled in.

In William’s play sessions, he often wanted to play hide and seek games, the kind of play seen in much younger children. If he tried to play with a puppet, it would remain inert, lifeless, and unable to speak. Sometimes he would run around the playroom in circles in an agitated way. In later months, he began to play about a bad boy who loved to wreck the playhouse, knocking over furniture and breaking things. After “bad boy” play, he would resort to playing about a good boy who constantly took showers.

As this was going on, the work with Estelle in parent guidance sessions focused on her high need for control of her son and husband in the face of her inability to tolerate being alone in the house. We worked on quieting her own anxiety and letting go of worries that something bad might happen to herself or her son. In some of our sessions, I saw both mother and child together and helped them to play and interact in more spontaneous ways using a child-centered therapy model. It was very difficult for Estelle to not dictate and structure her child’s every move. The experience of allowing him to take the lead and explore his own creativity and ideas helped Estelle to see him as separate. His constant need for her attention and his nonstop talking began to abate. We set up activities whereby mother and child would engage in separate activities in the home, in the backyard, and during school activities when parents participated. At first Estelle became anxious and controlling when such suggestions were made. She would become furious at me if I suggested normal childhood activities for William like going on a play date without her.

A shift in our treatment came when William began to want more separateness from his mother. He wanted to sleep in his own bedroom, which Estelle could be helped to allow. Then there was the instance when William was not permitted to go to a classmate’s birthday party and he protested. This was a good sign and we could use these dynamics to help Estelle see the need for her child’s own space and separation.

Over the course of several years, I was able to help Estelle and her son to develop a healthier attachment without the cloud of anxiety hanging over them. A major transformation for Estelle was her learning to tolerate the emotions that got stirred up whenever her son asserted himself and he wished to be separate and independent. Installing a sense of safety in being alone and separate was important for both parent and child. Both mother and child benefited from cognitive reframing of situations to feel that they could be safe in and out of the house and that Estelle could allow her son to be apart from her without a catastrophe happening. Addressing the underpinnings of the anxiety they both felt was essential to changing mother’s ability to leave the house confidently and to allow both herself and her son the confidence to be alone and to explore the world. This case example demonstrates the importance of addressing the meanings that the child has ascribed to exploring the world, their attachment relationships, past and present, and the family dynamics that may support or hinder their ability to develop social competence.

3.2. Generalized anxiety disorder

Individuals with generalized anxiety disorder often report that they have always worried and were born with a worry gene. Such children seem to be born with a nervous system that is intense and agitated or, in contrast, shuts down easily. Often there is a family history of parents or relatives who have all struggled with anxiety. These individuals can be on edge and irritable and worry about many things, some of which may be reasonable, others not so. Often sleep problems accompany the anxiety, the child reporting that they cannot shut their mind off at nighttime.

When the anxiety is pervasive from birth, it suggests a genetic component of the disorder, however, it may also reflect constitutional and/or temperamental attributes that impact the anxiety. There may also be a developmental component such as comorbidity with attention deficit disorder or a language learning disability that causes anxiety.

The literature exploring temperament provides some insight into generalized anxiety disorder. Thomas, Chess, and Birch (1969) identified nine variables of temperament in children during their first weeks of life, then followed this group of children into their child years. The results of this research showed that the individuals in the study retained similar temperamental traits from childhood into their child years. These variables are summarized as follows as they pertain to anxiety:

Certain clusters of these temperamental traits make people predisposed to be anxious. Most children who are anxious show a wide range of moods, fluctuating from happy and joyful 1 minute to agitated, worried, or withdrawn the next. Anxious children vary in terms of approach and withdrawal. They can be shy and withdrawn when faced with unfamiliar situations, but may be intense, outgoing, and overly alert, jumping into the situation before they have processed what is expected of them. They may have difficulty adapting to change and show attributes of ADD—a short attention span, high distractibility, and restlessness. Temperament is one variable that can predispose a child toward anxiety although it doesn’t automatically result in an anxious personality.

Another variable that can impact anxiety are certain forms of sensory defensiveness. These are further described in Chapter 9. A child who is tactually defensive will be fearful about being touched by others and will avoid crowds for fear of being bumped or pushed. Such children often report feeling claustrophobic in closed spaces. Sensory defensiveness can be the origin of some phobias that people acquire. For example, a child who is tactually defensive may have an aversion to anything touching their skin. Monica had developed a severe fear of needles and had overwhelming anxiety when she had to have blood drawn. She became overwrought if she thought a bug was nearby and might touch her skin. And she would feel nauseous if she saw something that had a lot of texture such as certain types of flowers or birds.

Anxiety can be spurred by auditory hypersensitivities where certain types of sounds can agitate the nervous system and cause anxiety without the child understanding why. Interestingly, if a child is anxious and listening to emotionally laden material, their middle ear muscles may contract and make the person’s voice seem muffled and hard to hear. That is why some people claim they didn’t process or hear anxiety producing verbal information. Finally, a child can become highly anxious because of visual clutter, a disorganized visual environment, or being in a closed-in space.

Children with movement sensitivities need their feet on the ground and hate being jostled in crowds or partaking in a variety of movement experiences such as certain sports, dancing, or amusement park rides. Fear of heights is commonly associated with vestibular dysfunction. It is not uncommon to hear that a child with movement hypersensitivities has panic attacks when required to move in ways that they cannot tolerate. For instance, Tyler had a severe fear of heights and couldn’t walk on bridges or go up steep stairwells, any of which would result in a panic attack.

Finally, developmental problems can fuel performance anxieties related to certain areas of competence. If the child is not well coordinated, he may grow up with the stigma of being last one picked for sports and thus lacking confidence to try movement activities. Performance anxiety related to motor skills such as handwriting, ball sports, or other physical ventures is typical for such a child. If the child has a language learning disability, they may not know what to say in conversations and develop anxieties about talking, especially when required to speak in front of a group of people. Some children diagnosed as selectively mute have this problem. Likewise stutterers become worse when the focus is on their speaking. Another commonly experienced form of anxiety is associated with executive functioning disorder and/or attention deficit disorder. The child may be unable to get started in tasks and not know how to organize and complete the steps necessary for task completion.

In each of these types of problems, the child’s difficulties can worsen over time if they are not challenged to overcome their anxieties and developmental difficulties early on. The child may develop a pattern of dependency on others and a view that they are not competent. For example, Stuart’s mother knew that he unraveled in novel situations and was extremely sensitive to any sensory stimulation, so she home schooled him. He rarely left the house for anything. His mother avoided placing any demands on him, even simple tasks such as making his bed or fixing a sandwich, so by the time he reached adulthood, he was completely unprepared to face the world. At age 22, Stuart didn’t know how to change a lightbulb, shop for groceries, or take care of himself in the simplest of ways.

In other cases, anxiety can be installed when the child has suffered from a caregiver or important person in their life (i.e., teacher, coach) who is highly judgmental or critical of them. This may manifest in performance anxiety when the child is overly aware of being judged or observed by others, then feel that they can’t meet standards set by others. The child may feel that they don’t measure up and are a failure, which impacts their confidence in all kinds of endeavors. Sandra grew up always being compared to her older, more competent sister, and it seemed that there was nothing she could do that pleased her parents. Her mother was critical of her weight throughout childhood and often made derogatory comments toward Sandra like, “Well, you can try doing that but what’s the point?” Sandra grew up feeling that she was worthless, stupid, and never able to succeed. Her mother even made comments to strangers, “Oh, she’s the pancake that didn’t turn out right” or “She’s clearly not the sharpest knife in the drawer.” No matter how hard Sandra tried at things, she often sabotaged her own performance by her anxiety.

A negative sense of self can develop anytime in a child’s life if they are prevented from important opportunities for self-improvement and development. For instance, the child who fails a subject in school, is bullied for their appearance or personality, or who doesn’t get picked for a team sport when he is clearly qualified are examples. Being treated poorly by someone or being judged severely can derail a child who might have otherwise coped well up to that point. Oftentimes girls with anxiety will report that the hardest years of their lives are between 9 and 11 years of age when they may feel ostracized or left out by “mean” girls. Jennifer, at age 17 years, reported that being bullied when she was 9 years old for being skinny and shy affected her so aversely that she made an active decision to isolate herself from peers.

3.2.1. Case example of a child with generalized anxiety disorder related to early loss

Marta was a 4-year-old child who came to therapy because of her extreme stubborn and irritable behavior. Her parents expressed how a day didn’t go by when she didn’t insult somebody with very extreme language. She would tell her friends things like, “Those shoes of yours look really poopy”. She would scream at her mother “You’re a bad mommy. Go away!” and at school one day, she threatened a girl, “I’ll cut you in half and throw you in the toilet!” She would scream at others who walked near her, “You’re yelling at me!” when all they were doing was minding their own business. Marta was very easily angered and blamed others when she said these cruel things.

At first Mr. and Mrs. T. thought that this was a protracted case of the terrible twos. As we talked about Marta’s high irritability, there seemed to be contributing sensory defensiveness. She needed her space and wouldn’t enter her preschool classroom if children were clustered near the doorway. She had to wear special seamless socks and hated to be hugged or touched. It was very hard for Marta to settle herself for sleep, thrashing about because the blankets never felt right to her. When she approached her parents and little brother, it was usually with a head butt or a hard punch.

Setting limits on Marta was almost impossible. She had daily outbursts. Her parents tried to reason with her at first, then would try to remove her from the situation. If they tried to touch her to steer her out of the room, she would begin to hit her parents and scream in their face. All transitions were very difficult for Marta.

As we discussed Marta’s history, there seemed to be a significant event in her life when the oppositional behavior began. When Marta was just 2 years old, her pet dog, Willie, became very sick. Her parents took Marta with them to the vet, and when the vet euthanized Willie, Marta let out a blood curdling scream, “Willie!”

It was difficult to build an alliance with Marta in our early work. She often resisted going into the playroom. She would yell things at me as I walked into the waiting room to greet her. “I hate it here. You do everything wrong. There is nothing good here! I’m never coming back!” Due to her extreme resistance, I focused initially on Marta just tolerating being in my play room for a short game, rewarding her for coming in by allowing her to visit my treat bag. On one of these sessions, she noticed the picture on my desk of my two pet bassett hounds. She immediately exclaimed, “They look like Willie, the beagle!” I asked her to tell me about Willie and what she remembered of him. All she could say was “He was my special dog.” That day Marta played in my sand tray. She built a big mountain and said, “Something is lost and the mermaids can’t find it.” In the story, the sharks come along, bury the mermaids, then send them to the big mountain where they couldn’t move or swim. Marta turned to me and said, “It’s a mean world!” Suddenly the play changed and another mermaid appeared who was able to save the other mermaids. Marta left the session in a notably happy mood.

In the upcoming month, I met with Mr. and Mrs. T. on several occasions to offer them parent guidance around how to manage Marta’s provocative behavior. They played waiting games with Marta (i.e., chant a song, then do the activity; red light, yellow light, now green light go!, etc.). It seemed that some of the problems with transitions had to do with Marta not knowing how to get started or how to end the activity without help. I suggested to Mr. and Mrs. T. to break down the task so that Marta only had to do one piece of the start-up, clean-up, or task at hand. When threats occurred, I urged them to validate her distress by comments like “I think you’re telling me how upset you feel that I’m not giving this to you.” and if that didn’t work, to ignore her behavior. We set up a system of rewards for her doing things when asked. When Marta hit or scratched her parents, they responded by giving her a bear hug from behind to calm her body.

The sessions with Marta were filled with play scenarios of violence. Almost as soon as I had gotten out the pirate ship for Marta, she began killing Captain Hook by shooting him with the cannon. I was often the recipient of the plastic cannon ball. Each time I dramatically enacted falling dead, then when she nudged my shoulder to check on me, I would sit up and laugh with her about getting killed.

The turning point in our therapy came when I brought a small stuffed beagle to give Marta as a reward for her doing well on her home behavior chart. She loved the little beagle dog and wanted to make a home for the dog. She made an elaborate bedroom for Willie out of a box that included a comfortable bed and blanket, a dog bowl and food treats, and strings mounted over the bed “to give power to Willie.” Each week Marta brought the stuffed beagle dog to therapy, she wanted to make more homes for him. We made at least eight boxes, all of which went home with Marta and Willie. Marta’s bedroom was filled with a long line of boxes for Willie.

It was another sand story featuring the mermaids. One day the mermaids were swimming, but felt very cold as snow fell upon them. They fell asleep because they were so cold, but when they awakened, they exclaimed, “Wake up! Someone has left a treasure!” The mermaids saw a glistening rock treasure from across the river, but as they realized this, the shark came along and swallowed their treasure. The shark swam over to the pink mermaid, tickled her and hurt her. Once again, the mermaids fell asleep. As night fell, the pony came to help the mermaids, but as he strained to help her, they both fell off the cliff’s edge. The pony cried when he saw that the mermaid was dead. Fairies appeared who tried to pick up the mermaid. Buckets of pink pixie dust fell on top of her but she was still dead. The mermaid’s friend tried again, this time sprinkling blue fairy dust on her and putting the sparkling treasure on top of her. Magically she came back to life.

Marta turned to me and said, “I’m not sad about Willie anymore.” In the upcoming months, Marta played similar stories with me, but the obsession about building homes for Willie stopped. Her behaviors and irritability improved dramatically as well. This is an example of a child whose unresolved grief over the loss of her beloved pet ignited extreme anxiety in her about death. Her way of dealing with it was to be aggressive and destructive toward others, much as she viewed the vet who euthanized her pet. Marta needed to express in therapy reenactments of killings and death before she could move on to a new zone of comfort, safety, and security for herself and her stuffed animal who resembled Willie. This process, coupled with the provision of validation, structure and limits, and messages of safety and security on many levels helped Marta to overcome her anxiety that persons or animals important to her would die.

3.2.2. Case example of a child with anxiety related to a family secret

James was initially referred because of his oppositional defiant behavior, attention deficit disorder, and problems getting along with peers. As I began working with James, it became apparent that these behaviors were largely driven by anxiety. To give you an idea of what it was like to be with James, I describe here a vignette from a group and individual psychotherapy session and my subsequent work with James and his family.

3.2.2.1. A therapy vignette

The skin on his neck mottles. That’s the first sign of trouble. James rocks his chair back on its hind legs. In a moment he crashes backward into the wall. He scoops up the game pieces. A game card shoots across the table. An unfriendly elbow rams into the child next to him. His voice volume inches up a few amps. My suggestion to take a break goes unheard. His face is beet red now. He ups the ante. If the boys don’t give in to him, all hell will break loose. He assigns himself the role of banker. The play money lies stacked in piles in front of him. Another boy challenges James. “You can’t do that! That’s not the way the game goes!” His chair flies backward in a thunk. James exclaims, “Are you calling me a cheater!?” Knuckles grind into the wall, then meet contact with the boy’s jaw. It happened so fast. Only 5 minutes had gone by since we started the game. I should have seen it coming. In the waiting room he was on edge, sparring with a boy over his game boy.

James and I are in the hallway now. He paces back and forth on the balance beam. I can barely keep up with his rapid speed, so frenzied and overwrought. He gradually winds down, me by his side. It seems to be working. He needs me to connect with that awful, distressed place that he goes to. Soon we’re sitting on the bench in the hallway. He leans his body into mine wanting my reassurance. Things will be OK. I place my arm around his shoulders and ask, “What happened today, James?” “I don’t know, I just snapped. I’ve been on edge all day long.” I take a deep breath and can feel his body relax into mine. “Let’s take a little time together.” The tears stream down his face and soon he is wracked with sobs. “Everyone is always against me. Nobody likes me. And my mom is too busy for me anymore.” More outpours. “Why am I this way? I keep having these anger bursts. Every day of my life is like this. I can’t stand it anymore.” I reply, “You know what, James? You’re helping yourself right now to make things better. You’re calming down and thinking what’s inside that makes this happen.” His body relaxed even more. As he dried his tears, I asked, “Do you think you could go back in there? We’ll play a bit more with the other boys, then we’ll have our special time.”

We manage to end the group on a good note but only because everyone walked on eggshells to avoid any other confrontations. It’s time for his session alone with me. James races eagerly down the hall to my room. He’s been playing the same story for the past 2 months. It’s important. Before I have even closed the door behind me, he asks, “Is the safe where I left it last week? Did you watch it for me?” “Yes, it’s safe”, I reply. “I took good care of it and made sure that nobody touched it.” There it was, buried under a fortress of foam blocks and pillows—The Silver Safe. He eagerly opens it to see what lay inside as if it were the very first time. His fingers sift through the gold and silver coins with sheer delight. Then he checks the secret compartment of the safe. He left a note there the week before, folded up tightly. He held the note clearly so that I could see what it said. “I hope I see you forever, even when I go to college.” “You didn’t read it, did you?” he quickly said. I was caught in the act, but I said, “Did you want me to see it?” “No!” he exclaimed, “But you can read it when I leave”. A close call. I tried to hide how touched I was by his message.

The play begins. He constructs a long tunnel of foam blocks spanning the entire length of my room. It ends in a small room-like structure. He carefully covers the tunnel with another set of blocks to construct a roof. Then he takes out the collection of balls and tests the tunnel to make sure they travel successfully to the small room. Once all adjustments are made in the tunnel, he asks me to sit on the receiving end where the small room lies. He exclaims, “Watch me do this!” Over and over he shoots the balls down the tunnel, one after the other until they arrive successfully in the small room. He wants me to admire him. “What a perfect tunnel you have made! And what an excellent shooter you are! Everything arrives perfectly and safely to their destination!” It wasn’t hard to figure out what this was about. Had he consulted the book on my shelf about Oedipal Complexes? He could have written the chapter.

The shooting abruptly stops and he deconstructs the tunnel. He goes to the safe. “I need to hide the safe. Will you watch it for me this week? Don’t let anyone touch it or know that it’s here.” How could they not notice the big pile of pillows and foam blocks that hid the safe? They protruded into my room, glaring loudly “There’s something hidden here!” It was clear that James was holding on to a very big secret that was disorganizing him. As we end our session, James turns to me. “My Mom’s picking me up today with my brother. I hate it when he comes along.” “Why is that?” I inquired. “I don’t get along with him. We have nothing in common. He looks different. He acts different. My mom understands me. We’re the same.” I simply replied, “You really connect with your mom. Every time I see you with her, I can see how close the two of you are. Is it important to you that you and your brother share more things in common?” He paused, then replied, “I don’t know how to be with him. It’s the same with my father.”

That week James’ mother called me, wanting to speak with me in person. When she came, I put away all the blocks and pillows so that James’ construction would not be revealed. The session began with her talking about her struggles in managing James’ erratic and uncontrollable behavior. Then she turned to me and said, “There’s something I should tell you. I’ve never told anyone, not even my family. If they knew, I would face such disapproval. I can’t deal with that on top of all the other disapprovals they placed on me while growing up. After we had our first child, Michael, my husband was diagnosed with his seizure disorder. That’s why he doesn’t drive and works at home. Michael also has the same seizure disorder, but in a more severe form.” I already knew about the seizure disorder, but I listened carefully to her message. She continued, “We wanted another child, but we couldn’t take the risk, so I had a sperm donor for my pregnancy with James. He doesn’t know that John is not his real father.” I was surprised that I felt stunned by this information when it made complete sense to me. It was so obvious. I replied, “John is his real father, just not his biological father. You have had a lot to hold, keeping this information so close to your heart.” I wanted her to allow John to own his fatherhood, but I also resonated to the terrible shame she was holding onto. I continued, “Somehow you have to find a way to tell James. This is not a shameful thing. It’s natural and it’s how he came into this world.” She began to sob. “It’s too much for me to bear.” We talked for a while, then at the end of the session I thanked her for sharing her secret with me. I turned to her and said, “This is important information that James needs to know. When you feel it’s time, you and John will tell him. It will be a relief to all of you to do this. He’s ten years old now and he’s mature enough to know. We can talk more about how to say the words.” As she left my room, I thought to myself, “He already knows.”

3.2.3. Case example of a child understanding her anxiety through play

Sasha was a 9-year-old girl who had been coming to see me for over a year for severe anxiety. She could never articulate exactly what it was that triggered her anxiety, but she was flooded with anxiety almost constantly. Sasha was very quiet and withdrawn most of the time and often pulled out her hair, masturbated in privacy to self-soothe, and chewed her fingers until they were raw. An adult asking her a question, a peer approaching her, or any change in routine would set off these behaviors. What worked best in helping Sasha was to create forums for her to express and understand her anxiety through play. By bridging nonverbal enactment of symbolic material with verbalizations of insights, Sasha began to make good progress in conquering her anxiety. Here is an example from one of our sessions.

3.2.3.1. Vignette

“I didn’t want to come today.” I gaze at her small body lying inverted in the beanbag chair, her auburn hair cascading toward the floor. Her eyes cast downward. “I don’t know what to say. I hate talking about my feelings.” Her voice is filled with sadness. A long pause. I wait. Then she says, “But, I always feel better when I do.” Speaking softly, I say “I’m glad that you came. We can just be together. We can talk or play. There are many ways to express feelings.” She climbs out of the beanbag chair. I notice the imprint where her body laid. I watch as she fingers the table edge. She stops in front of the paper and markers. Sasha loves art, but that is not for today. I sense her listlessness, the heavy weight she holds in her small body as she moves. She speaks without looking at me. “I want to do a sand story.” Her tiny fingers trace along the sand’s edge. “I don’t know what to do.” I reassure her, “That’s fine. Just see what happens.” Quietly she pours bands of colored sand—pink, green, and blue. She picks the red sand and pours a large pool in the center of the tray. She places colored stones carefully, forming a wide ring around the red sand. Time feels suspended in slow motion as she works. I observe calmly and quietly.

Sasha places a little baby doll in the center of the red pool of sand. The colored stones glisten in sharp contrast to the colored sand. Outside the ring on pink sand, she places a small kangaroo. On the opposite side standing in yellow sand is a little bunny. On the upper far side she places two little frogs carefully on green sand. And on the far bottom side in blue sand, she places a small giraffe. The scene has been set. Silently Sasha circles her finger around and around the circle of colored stones. She speaks so quietly, I can barely hear her. “That’s me in the middle. My friends (pointing to the frogs) and my sister (the bunny) are so far away. My mom (pointing to the kangaroo) and my dad (the giraffe) don’t know this, but I’m on fire. I’m burning up and no one even notices.” I am stunned to hear that she is on fire.

I quietly watch as her story unfolds, all the while remaining calm and present. She pours more red sand on her doll figure. The baby is almost covered with red sand. I can feel a lump rising in my throat, a tightening that I had not been aware of until this moment. Then I say, “I wonder if anyone knows what is happening to you.” She replies, “Yes, my mother. She gets a fire extinguisher, but she can’t reach me. There is no way into the fire.” We are both suspended in time, watching this terrible tragedy, a small baby alone in the middle of a fire. How could this happen to her?

She reaches for a horse and says, “A wise horse comes along. She builds a bridge from the stones to reach me. The frog friends exclaim, ‘Look! Sasha needs us! Let’s go help her!’ The giraffe father follows the tracks in the sand left by the horse. He says, ‘Let me follow this path and see where it goes. He finds the bridge. When he sees me, he says, ‘Come out of the fire, Sasha. The horse told me where to find you.’ The wise horse carries the baby on her back away from the fire and out into the world.” She brings the baby onto the blue sand and surrounds her with all the animals. Sasha turns to look at me and says, “Now she’s safe. She has lots of friends.” It is all I can do not to cry. I am deeply touched by her moving story. Whose tears do I hold—hers or mine?

We are sitting face to face now. I feel her breathe close to me. She says, “I’m too sensitive inside. I feel things more than I should.” I reply, “Like the baby in the fire. It is overwhelming for you, isn’t it?” “Yes. My sister, Chloe, takes advantage of me because of it. She does things that hurt my feelings all the time. She teases me.” An image forms in my mind—a soft, warm gold clothe enfolds the two of us. “Maybe you could pretend that you are a turtle with a good shell that protects you whenever Chloe bothers you. Let her words bounce right off your shell.” A half-smile creeps on her lips. “I could try that. That might help.”

She gazes out the window, then turns toward me again. “There’s more I want to say. I think about violent things happening to me, like someone cutting off my ear while I’m asleep. I’m afraid all the time.” I reply, “When children are afraid, they need to find a safe place. They need a safe person to help them know that nothing bad will happen to them. Do you feel safe in your house?” “Sometimes, but my mom and dad fight all the time. I hear their angry words and I hide behind my bookshelf hoping they will stop. My mom has more time for her work than for me. She used to cuddle with me when I went to bed at night. That made me feel good. Now there is nothing.” “You know, Sasha, it is not hopeless. You can find a voice. I will help you do it, like the wise horse who helped the baby. We can tell your mom and dad how you feel when they fight. They probably don’t know you hide in fear and that you have such scary thoughts at night.” She looked at me and said, “I’m afraid to tell them. They’ll yell even more if I do.” I replied, “Your parents love you, but their fights are not a good thing. They make you afraid. Do you want to write a letter to tell them how you feel when they fight.” “OK.”

Wistfully she said, “I don’t have any art projects in me anymore. They died inside of me. I wish I was six years old again. I was happier then.” I put my arm around her shoulders and said, “I’ll help you get your art back again. Happy thoughts lived in you before, and they can live in you again.” She smiled and said, “I’m glad I came today. I feel better.”

4. Posttraumatic stress disorder

Almost everyone can think of a time in their life that they developed anxiety in response to an environmental catastrophe. A difficult time for many people was the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington DC. Not too long after this event, the children living in Washington, DC were again traumatized for several months when two snipers attacked innocent people as they put gas in their cars or went shopping. People ran zig-zagging across parking lots in fear that they might be shot during everyday activities. Parks were vacant and people were fearful to go places, worried that any white van might house a possible sniper. The people living in Washington, DC were further traumatized that year when there was the scare of anthrax being delivered in the mail. Letters and packages were rerouted through special postal offices to screen for the deadly poison, some people took cipro to protect against possible exposure, and other people even opened their mail wearing rubber gloves and face masks.

These kinds of events can have long-lasting effects on people’s anxiety. Other kinds of traumas might be a terrible flood or hurricane damage, leaving a child homeless or enduring terrible loss of pets and loved ones. Following any of these kinds of tragedies, there is an increase in anxiety in the population. Once the event passes and life returns to normal, the anxiety usually abates, but for some people who are more sensitive and reactive, the fear may not go away. One mother reported that for years her child was afraid to be near a window and lay down in the back seat of her car because he was fearful that a bad guy with a gun would shoot them. When a child remains anxious after such events, they often restrict their activities, they may hover closely to their children in an effort to keep them safe, and they may be easily triggered by similar events in the news, which puts them again in hyper alert mode.

Unfortunately some children are subjected to horrible abuse or trauma either growing up or in their relationships with others. In many cases the child learns the cycle of abuse and interacts with family members in unhealthy ways. Physical and sexual abuse at any time in a child’s life as well as exposure to violence at home or in the community can induce severe anxiety. Some individuals dissociate or repress memories to cope with the trauma, thus making it more difficult to rework the trauma on a verbal or conscious level.

Children can also be traumatized by other’s anxiety about an upcoming event. For instance, if a child hears that everyone who takes a particular exam flunks the first few times they take it, they may go into the test taking with extreme anxiety, even if they are not predisposed toward anxiety. Anxiety can be induced by having too much to do in not enough time or having to perform up to too high a standard for one’s own ability. Anxiety may be induced by living in a house or apartment that is extremely cluttered.

In the next section, several cases are described that demonstrate different ways of addressing types of trauma.

4.1. Case example of an adopted child with violent outbursts

Nick was adopted in the preschool years after living 3.5 years in an orphanage in an Eastern Bloc country and soon after he came to live with Mr. and Mrs. F., it became apparent that he had fetal alcohol syndrome and autism. As he entered his teen years, he became extremely impulsive and angry, addicted to video games, and constantly wanting to be rewarded for complying with the smallest of requests. By the time Nick was 16 years old, he was a tall and stocky child who could fly into a rage if asked to come for a meal, to take a shower, or to do his homework. He frequently would kick holes in the walls, slam doors violently, and break valuables around the house. When his father denied Nick the purchase of a video game, Nick kicked the windshield of the car while his father was sitting behind the steering wheel. The windshield shattered, then Nick screamed at his father, “I’m going to kill you!”

His parents felt helpless around Nick, unable to control his rage. His parents were scared that Nick might attack them in the middle of the night while they slept in bed. There were also incidents when the police came to the house after Nick had taken a hammer to the walls and the younger son called the police in fear. Clearly the entire family was traumatized by Nick’s violent and impulsive behavior.

Mr. and Mrs. F. felt that they were a failure as parents because they hadn’t prepared their son for the world. Inside the father hated his own child and thought how he loved the dog more than Nick, which gave him enormous guilt. We worked to help the parents overcome their PTSD by creating a safer home environment, an internal sense of safety, and cognitive reframing. First, we found a residential placement for Nick that helped him to finish high school while working on his violent behavior. Nick came home for weekend visits, which caused his family great fear, but the school was helpful in directing them on how to respond to his behaviors each weekend. Mr. F. could articulate beliefs that he held about himself and, with my help, coupled them with visualizations of safety. For instance when Dad felt trapped by his son, he would say to himself, “I can back away when Nick pushes my buttons” coupled with visualizing a safe place like looking out at the mountains and imagining both himself and Nick calm and safe. The mantra “I can get through this” helped him to back away and not enter violent outbursts. It also helped Mr. F. to think about what Nick really meant when he said, “I want to kill you.” In reality it meant that Nick was so overwhelmed that he couldn’t stand being himself. Interestingly, shortly after these sessions, Nick wrote a letter to his mom and dad saying that when he awakened in the morning, he didn’t say to himself that he would do bad things. He started the day hoping for a fresh start, but what he wanted most was for his parents to get to know him and not judge him as he struggled to control his moods.

4.2. Case example of a boy with posttraumatic stress disorder

So many things were scary in the world for Daniel. His mother read him a story one night. It was about a baby deer who went into a dark forest. A storm came along and before the small deer knew it, high ocean waves flooded the forest. Would the deer be safe? That night, Daniel had nightmares. The next day he made a fort and hid inside. His mother tried to coax him to come out, but all he could say was how afraid and unsafe he felt.

When I saw Daniel for therapy, he frequently played a story about Super Duper, his older brother from Russia. Daniel hadn’t seen him since he went to the orphanage at age 2 years. Who knew what had become of him? The story went like this—Super Duper could do anything he wanted. He drove airplanes and cars wild and fast, crashing wherever he wanted. I was assigned the role of policeman who tried to stop Super Duper before he hurt himself. But nothing could stop him! Daniel turned to me, “We have to stop this game NOW! It’s too dangerous!” I asked him, “Do you feel like Super Duper today? Are you afraid that your feelings will destroy you?” He began to shake. “Nobody can keep me safe.” “Just like how the policeman couldn’t help Super Duper. You must feel very alone with these scary feelings of yours. It’s just like the flood in the forest, isn’t it?” I said.

Then he said, “Let’s write a story. I’ll tell it and you can write my ideas down. It’s called—The Best Ocean Liner Ever. There was an ocean liner sailing on the ocean. It sailed fast past lots of icebergs, never getting hurt until one day, the iceberg was just too big and hit the boat. The ocean liner sank. The captain was crazy and sank with the boat. But the boat was pulled up and a very smart construction crew fixed the boat. At 3:00 in the morning, the boat was ready to sail again with a new captain. The boat sailed safely all over again in 1999 on July 23rd. The end.” I put my pen down and turned to Daniel. “That is a very good story. It makes me think that even though bad things happened to the ocean liner, things could change. It got a new captain and could make itself safe. It reminds me of you today taking charge of your scary feelings.”

At home the house was filled with enclosures that he had assembled with furniture and mattresses. If his mother touched them to clean the house, he would shriek and tremble. “Don’t touch them! I need them!” It was always the same story. He was a small cub who had just come to a new home. He wanted his mom to walk through the house as if it were the very first time Daniel had ever seen it, finding the rooms. Then he pretended to call his brother, Super Duper who would be 18 years old by now. There was no phone connection or he wasn’t home. Other times he connected with him and he said, “Come play with me!”

Most weeks he played the same story in his sessions with me. He constructed a large cave out of foam blocks, chairs, the puppet theatre. He was a cub and would say, “There’s something scary inside there. You wait here! It’s dangerous!” I would ask, “But if it’s dangerous, wouldn’t you feel safer if I went with you?” “No! Stay here!” Who was he protecting? He went into the cave and I would hear all kinds of sounds like animals fighting. I asked, “It sounds terrifying! How horrible it is to go someplace so scary, and all by yourself!” After a while, he would emerge and growl at me like a bear. Then he said, “There are hunters coming who want to shoot the bear. Can you be a guard to protect the bear in his cave?”

It was another therapy session and this time he wanted to make two separate homes, one for me and one for him. Sometimes our houses were made and stocked with pretend food, treasures, and toy telephones. He called me on the telephone, “Come on over and visit!” This went on for a few times, him opening his home to me, and sharing his treasures. Then suddenly, his house exploded with bombs that were hurled at it from dangerous people. This was the first time he let me be with him while bad things happened to him. It was progress. He snuggled up against me and said, “Keep me safe, please.”

“Let’s write another story. This one is called ‘Look Out Ralph!’ A little cub named Ralph comes home. He wants to be taken care of. He grows into a grizzly bear who is ferocious and fights hunters. But he is also very gentle and takes care of a turtle and frog who are his pets. He faces all kinds of dangers like catching snakes hidden in the cave. You guard the cave and watch the bear as he does these heroic feats. You also make sure that nobody gets hurt. But then the cave opens up and out comes the grizzly bear. He’s your friend, but he stays scary to everyone else.”

5. Strategies to alleviate anxiety

In this next section, we look at a variety of strategies that can help a child to quiet anxiety. These strategies should be used in combination with dynamic developmental psychotherapy such as that described in the previous vignettes in order to address the emotional and developmental needs that underlie the anxiety.

1. Validate the child’s distress: Important people in the child’s life should reflect how the child is feeling, then step back and allow their validation to be absorbed with an open mind (see Skill Sheet #9: Validation).

When a child seeks validation, they need to feel that someone else understands the distress they feel and appreciates the good things about their personality. The key to giving validation is to avoid going on and on about the problem but to simply reflect what you think the child is feeling. Wait for the child’s response, and listen to the child’s point of view. Validation helps the anxious child know that what he is feeling is real even if it is not rational to feel that way. For instance, whenever Anita told her mother how paralyzed she was by anxiety, unable to do even the simplest of tasks in her life, her mother would dismiss her and say, “You just need to move on. Stop being so anxious.” This only deregulated Anita even more. As Anita was 11 years old, I coached her to seek validation by asking her mother to come see how hard it was for her to clean her bedroom because the dolls on the shelves needed to be in precise order and nobody else was permitted to touch the dolls. Anita was able to show her mother in the moment how overwhelming her anxiety could be. She asked her mother to please try to understand and not dismiss her anxiety. This was a first step for Anita. Her mother began to understand the paralysis that Anita felt day in–day out about many daily activities, from drawing a picture until it was precisely right by Anita’s internal standard, to walking the dog in the correct sequence and route. It was then that they could work together to figure out how to move through the initial threshold of feeling flooded. As Anita’s mother was also quite anxious by nature, it was necessary for Anita to get the assistance of her father to “get her started” on activities. Once she was set in motion, then Anita was more capable of sustaining the task at hand without getting stuck in her anxiety cycle. It made her far less anxious to feel that her mother understood the difficulties that she was having at home and school, thus lessening the anxiety she experienced by being judged. If a child is unable to impart how overwhelmed they feel to others by talking about it, it is very helpful for them to show important persons in their life what it is like for them.

2. Make time to self-calm and quiet the body and mind through relaxation, guided imagery, and deep breathing (see Skill Sheets #1: Self-soothing; #7: Mindfulness; and #8: Systematic relaxation).

Dealing with anxiety often involves helping the child to feel grounded, safe, and in control. When life is scary and unpredictable, it is important to engage in daily, soothing activities that give the child pleasure and quiet the body and mind. The child should take at least 20 minutes per day to relax their body by using guided imagery or progressive relaxation. The child should find a quiet place and sit in a comfortable chair or lie down on a soft mattress as long as they don’t fall asleep. Some children find sitting in a soft beanbag chair with a weighted blanket on their stomach helpful to this process. Dimming the lights in the room and assuring that there is no noise in the environment is also helpful. Sometimes playing soft music in the background helps set the tone for self-calming. The child should picture a serene place that relaxes them—the beach, going to the mountains, etc. Then concentrate all thoughts on the sensory aspects of that place—the sights, the sounds, smells or tastes, and the things they feel. If a random thought comes into their mind, they should just notice it and let it float away. It is important to refocus thoughts to a safe haven while breathing slowly and deeply. For children who are unable to visualize, use visual displays like a colorful water toy that is calming (i.e., colored water drips through slowly moving gears).

Diaphragmatic breathing is very important to quieting anxiety. It is best for the child to lie down if possible to practice deep belly breathing, focusing on breathing slowly. Place a hand on the abdomen to feel its rise and fall. Some children like visualizing a light that flows with the breathe—a gold, green, purple, or blue light that comes in with the inhalation, fills the abdomen, then flows out slowly with exhalation. Techniques like visualizing the colors of the rainbow floating in with each breathe can be very peaceful for the child. The child should notice the rhythm of their breathing, trying to breathe deeply and slowly. One can also focus on counting breathes, pushing all thoughts out of the mind. The child should focus on saying the number followed by “breathe in, breathe out,” then move onto the next number.

3. Exposure (see Skill Sheet #12: Thinking with a clear mind).

Overcoming anxiety requires that the child expose themselves in increments to the thing that is frightening. Writing down a list of all the things that cause anxiety is the first step. Place them in sequence on a ladder grid ranging from 1 to 10 from the easiest to the hardest to do. Then write down all the thoughts that come into their mind as they engage in that particular activity. Negative cognitions commonly expressed might be things such as “I will fail. I cannot succeed. I have to be perfect.” Select the easiest one on the list and that is the starting point. Take the negative thoughts that occur in that situation and write down the facts about the situation, taking all feelings and negative thoughts out of the equation. For example, “It’s a piano recital. They call it “playing” music for a reason. Let the audience play with you as they listen. Nobody else in the room besides the teacher will know the piece and if I make a mistake, just make it sound like part of the piece.” The child should then focus on quieting the anxiety so that they can approach the situation without letting anxiety take over.

Tony had developed a pattern of avoiding school at all costs, often complaining of terrible stomachaches and even vomiting, but only on school days. On the weekends he felt just fine. Medical work-ups could not find anything wrong, so we speculated that the stomachaches were psychosomatic and anxiety driven. Exposure is the technique of experiencing what one fears in order to learn to not be afraid. Setting appropriate goals for Tony was important. He had little motivation to leave home and at first, his parents allowed him to play video games when he complained of feeling sick. When they learned that Tony’s problem was likely to be anxiety, they worked with me around developing a plan to help Tony get to school and remain there through the day. The only thing that motivated Tony to go to school was the photography club. He had only one friend who went to a different school. We arranged small rewards throughout the day to help Tony with each step in the sequence. If he could get dressed and be downstairs by 7:30 a.m., his mother cooked him his favorite breakfast. If he could get in the car in a cooperative way, he could play on the ipad. Once they arrived at school, the principal greeted Tony. He was given one pass per day for 15 minutes that he could use whenever he chose to take a break in the library, the counselor’s office, or the movement room. If he abused the pass and didn’t return to the classroom after 15 minutes, he lost his pass for the next day. In addition to our school program, we facilitated Tony’s interest in photography and practiced going places where he could take interesting pictures. The teacher who ran the photography club collaborated with me around coming up with fun projects that were motivating for Tony.

4. Changing behavior

Often the anxious child engages in unproductive things that derail their ability to cope and change. The instinct when a child becomes anxious is to escape from the situation, avoid the task completely, or engage in a maladaptive behavior rather than to focus on productive actions that will alleviate the anxiety. Here is a template for changing behavior.

a. Get validation: The child should learn to alert family members or teachers how difficult a particular task might be for them so that others will be patient and understanding as they begin to work on their goal. For example, Amanda would get off the school bus and would make a beeline to her glider chair. Once in the chair, she would rock vigorously for several hours to avoid doing homework, chores, or interacting with family members. If forced to work on these things, she would carry on and scream for hours, protracting the process and making everyone miserable.

b. Set a goal: What the child wants to happen. What are the target behaviors? It is usually best to work on one thing at a time, rather than attempt to make many changes. For Amanda, her goal was to relax and get out of her responsibilities. When her parents acknowledged how overwrought Amanda felt from a day at school, they asked her how they could help her relax, but to also engage in the tasks of life.

c. Commit to working on this goal: We set up a chart of what time to begin relaxing in the glider chair for 20 minutes, doing 20 minutes of homework, then cycling back to this one or two more times. Amanda agreed to participate in a resource class at school to do half of her homework before coming home. She also liked having the cool teenage girl down the street come over to help her with her 20–20 relax per work program.

d. Use positive reinforcement to help install the desired behavior. If Amanda was able to accomplish finishing her homework, she earned points toward other movement equipment that would help her to relax. She loved the idea of ultimately winning a trampoline for the back yard.

e. Shape the desired behavior by encouraging successive approximations of the desired behavior. We shaped the relax-homework (or chore) routine for Amanda by placing a signal watch on her wrist that cued her at intervals when to move onto the next step. If she could finish her homework before dinner, there was still time after dinner to play a board game with her parents.

5. Observing limits (see Skill Sheet #14: Observing limits).

As anxiety is so infectious, people with anxiety often find it easier to give into other people’s demands rather than entering a conflict. Others in the household may give in to avoid stirring up trouble. For instance, Lizzy had a severe bug phobia, which interfered with her going on school field trips and family camping trips or even walks in the park. Just the mere sight of a harmless bug like a ladybug or a butterfly could set Lizzy into a shrieking fit. We had embarked on a bug plan in therapy where we talked about bugs, looked at pictures and videos of bugs, and tickling her hand as if a fly had just landed on her. As there were several upcoming events that Lizzy had to participate in, we discussed what her limits were for a daylong school hiking trip to the woods. Lizzy decided that she would douse her body with insect repellent and wear a long-sleeved shirt, long pants, and a big brimmed hat to cover her body. She felt that if a bug landed on her clothing, she would tell the teacher or ask a peer to brush it off, but if it landed on her skin, she would need to call her mother to calm her down. It turned out that there was very poor cell phone reception where they went that day, so Lizzy was forced to allow the teacher to talk her down from her usual screaming fit. Originally Lizzy wanted her mother to come and immediately pick her up from the trip if a bug landed on her, but we pointed out that both her mother and teacher had limits too. Her mother had a young baby at home and couldn’t make arrangements to come on the hiking trip. Likewise, her teacher couldn’t abandon the other children or ruin the field trip because of Lizzy’s bug phobia. It actually was helpful to talk with Lizzy about these constraints so that she could realize that her bug phobia negatively impacted a lot of people.