Historically, games have long had a presence in education, from classroom exercises like spelling bees and geography-themed bingo to academic competitions like debating clubs and Model UN. It shouldn’t be terribly surprising, then, that some successful video game franchises have focused on learning and been welcomed in schools:

The Oregon Trail. A classic game originally created in 1971 that simulated pioneer life in the 1840s and presented lessons in history and ecology.

Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? A series of mystery-themed video games that taught geography.

Math Blaster. A space adventure game that drilled mathematics.

Developers of educational video games have traditionally taken an approach that some people have compared to chocolate-covered broccoli—applying a thin game veneer to material that is recognizably unaltered from traditional classroom lessons. There’s a certain cynicism in this way of thinking that doesn’t highly regard either education or games. It implies that education is an inherently unpleasant thing and that no enjoyment is to be found in subjects like math, geography, science, or literature in and of themselves. It also implies that the role of educational games is to obscure the actual educational activity so that learners are more willing to bear the unpleasantness of learning. In addition, the quality of the player experience in such games has often been sacrificed in service to educational objectives.

In recent years, researchers, educators, and game designers have explored new ways to use games for education and training, for both children and adults, and have even transformed traditional models of learning through gameplay. In the modern view, games have unique attributes that can enable means of learning that aren’t otherwise easily available. These attributes create opportunities for UX designers to create compelling learning systems.

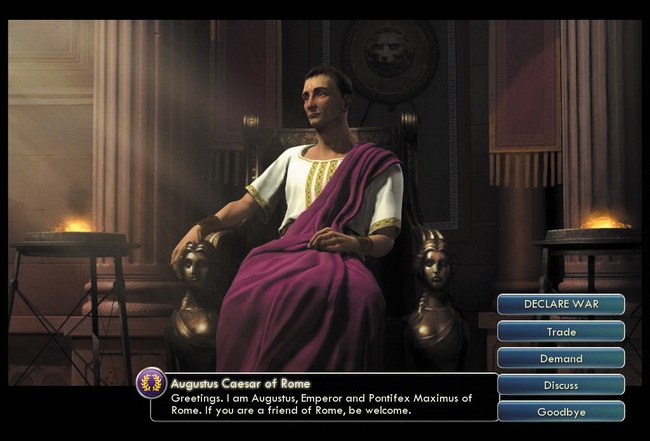

Even a game built purely for entertainment can demand tremendous effort from players to learn how to succeed at it. Civilization V, for example, in which players must build and manage societies spanning all of human history, presents well-structured learning that players acquire voluntarily (Figure 12-1). The game also creates an opportunity to reflect on human history and to experiment with both the internal and external factors that lead to the rise and fall of different regimes.[42]

Games like Civilization V can add an entirely new mode of learning to traditional means of instruction—one that can form a very effective complement to textbooks and lectures. This viewpoint assigns games a much more sophisticated role in learning than they have traditionally occupied, and it finds an intrinsic joy in learning for its own sake. Designers creating games for learning today should build experiences that marry subject matter to people’s innate fascination with new ideas.

This chapter explores how UX designers can make use of the unique advantages that games create for learning. First I review the qualities of games that make them suited to learning. Then I discuss specific ways in which designers are using games in learning environments. Much of the current work being done focuses on children, but the basic principles generalize well to any audience and can be repurposed for professional training, customer education, or awareness programs.

There’s something of a cultural bias against video games, regarding them as anti-intellectual pursuits that numb their players’ brains and offer no meaningful gain in knowledge. In fact, video games have certain inherent advantages that make them powerful tools for facilitating learning, often in ways that are difficult to accomplish by other means.

One of the reasons learners become discouraged is that they lack a feeling of agency, or personal control over outcomes. When people come to believe that the learning process is outside of their control, they may give up on learning altogether. Some children think they cannot succeed in math class, and many adults feel powerless when trying to use a computer, for example.

Video game players, on the other hand, are entrusted with the responsibility of being fully in charge of something, giving them complete control over outcomes. Games thus create a strong sense that winning and losing are within the player’s power. They also give players the ability to structure the experience themselves, learning what they need to know as they need to know it. The player is in a position of power, which can be a valuable role for learners who lack a sense of power in real life.

Furthermore, the process of becoming competent with any game requires players to gain mastery over a domain of knowledge, promoting a feeling of ownership of the subject matter. In many games, success is directly tied to the player’s depth of understanding of the game world. Putting players in competition with one another can increase the drive to master the domain, so that the players really have to know their stuff in order to win.

The PC strategy game Sins of a Solar Empire illustrates principles of both agency and mastery in games (Figure 12-2). Each player commands an entire fleet of space vessels locked in an interplanetary struggle for dominance. The fate of the fleet rises and falls with the player’s choices; no one is preempting the player’s control over the outcome. People playing Sins of a Solar Empire must also learn the intricacies of its universe, such as its 45 different types of space vessels and the unique strengths, weaknesses, behaviors, and alliances of each. Substituting spaceships for cells and tissues, a very similar game could be used to teach anatomy and physiology, and to demonstrate how the body defends itself against disease and infection.

Will Wright, designer of The Sims and SimCity, coined the phrase “failure-based learning” in reference to the way games allow players the latitude to fail and fail again until they get it right. In this view, failure is an essential part of the learning process, which is a departure from the traditional view of failure as proof that no learning has occurred.[43]

Figure 12-2. Players need to master the complexities of managing their own personal space armada to succeed in Sins of a Solar Empire.

Two key characteristics of games make them well suited to supporting failure-based learning:

Players appreciate the unwritten rule that games are designed in such a way that success is always possible, even if it’s very difficult.

There are no permanent consequences of failing—only temporary setbacks. So games give players every reason to try and try again.

Failure-based learning offers people the opportunity to understand their failures better, inviting a cycle of critical thinking and problem solving. To increase their chances of success the next time around, learners need to try first, then analyze why what they tried didn’t work, then develop hypotheses about how they can minimize those factors, then try something new, and so on. Failure is an indispensable part of this process because it brings learners closer to the right answers by exposing problems in their reasoning and creating the opportunity to correct those problems.

Failure-based learning also teaches players the important life lesson that you don’t need to feel paralyzed by failure. When something doesn’t work, just regroup, change your approach, and give it another go. This is a very pragmatic way of learning because it reflects how many things actually get done in the real world. In UX design, we go through multiple iterations of design and testing before rolling out a product because we expect that some things won’t work. Relatively few difficult challenges can be overcome on the first try. When people don’t develop a tolerance for failure, they limit their potential for success.

Video games are a wonderful way to acclimate people to failure and to help them develop the skills needed to surmount difficult challenges. Angry Birds provides a great example (Figure 12-3). The objective of each of the hundreds of levels in the game is the same: to destroy the malevolent green pigs by using a slingshot to hurl different types of birds into the pigs’ fortresses of stone, wood, and ice. Players are given a limited number of birds to throw, and they must determine how to use the specific attributes of each type of bird to attack the unique construction of each fortress. Angry Birds is a model of failure-based learning because players almost always need to try each level several times. With each try they come to understand the problem a little bit better—discovering weaknesses in the fortress’s structure and better tactics for using each of their birds. As soon as the player finally succeeds, a new challenge is presented and the process starts over again. Players spend much more time failing in Angry Birds than they do succeeding.

Figure 12-3. I played this level in Angry Birds a good 30 times before finally clearing it. Each time, I learned a little bit more about what works and what doesn’t.

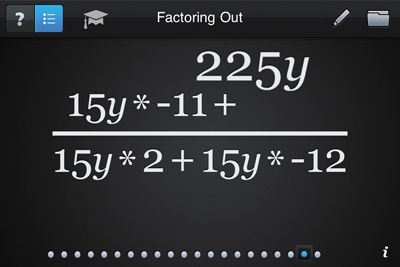

Algebra Touch for the iPhone is a game that asks players to solve increasingly difficult equations as new structures or axioms are added at each level (Figure 12-4). Each problem is solvable, no matter how difficult, and players are free to fail as many times as they need to before arriving at the correct solution. The core mechanic of Algebra Touch is, in fact, not entirely dissimilar from that of Angry Birds. In both games, players need to understand the unique properties of the elements provided to them, and then must use these elements to reduce a structured object to a simpler state. Both games enable failure-based learning, allowing players the latitude to keep trying until they get it right.

Video games give learners the opportunity to gain hands-on experience with the things that they’re learning about. Because they face no real-world consequences, players are free to ask “What if...?” and explore the boundaries of a game space to see what happens under different circumstances. In this way, games encourage a spirit of inquiry and exploration. Similarly, early versions of Microsoft Office came with very useful built-in tutorials that allowed users to learn how to use the applications by working through examples. The help system in recent versions has taken a big step down by replacing these active hands-on learning systems with straight copy and passive videos.

Importantly, games can closely mirror the conditions of the real world without putting any real-world objects at risk. Although you wouldn’t give students unsupervised control of a real chemistry lab, there’s no downside to letting them blow up a simulated one. Games can give players access to things that would be too expensive, impractical, or unsafe for them to use in the real world. Flight Simulator, for example, lets players get practical experience flying a plane without any of the risks.

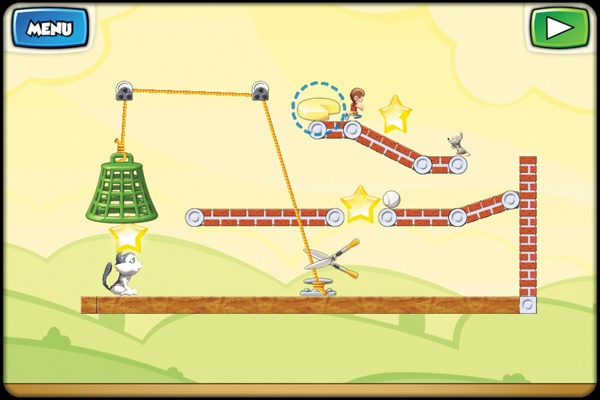

The Incredible Machine for the iPad is one such virtual lab. It allows players to experiment with different configurations of Rube Goldberg devices to achieve a stated objective (Figure 12-5). When the completed device is run, objects fly around the screen following the laws of physics (though in two dimensions). There are many possible paths to success, so players need to use ingenuity and experiment with the utility of devices ranging from catapults to rockets.

Figure 12-5. In the process of playing The Incredible Machine, players learn a lot about basic physics, including the laws of motion, gravity, and energy.

There’s some controversy about whether education is more effective when a teacher tells and then shows, or shows and then tells. To some extent, students need background knowledge to make sense of an experiment, but it’s also much easier to learn the theory behind something after they’ve had some experience with how it works.[44] Some research indicates that students get the most out of a hybrid approach in which they move freely between theory and experience.[45] It’s easy to imagine interactive e-books being developed that integrate theory and practice by interspersing small interactive games to illustrate particular points throughout the text.

Learners can be inhibited by an inability to imagine putting the things they’re studying to productive use in their own lives. Studying astronomy makes sense if you can see yourself becoming an astronomer, but if not, then the time spent learning about it can seem pointless. Games can be valuable in this regard because they encourage players to try on different identities, giving them the opportunity to imagine themselves as scientists, managers, or titans of industry. This kind of role playing can create aspirational targets for self-development.

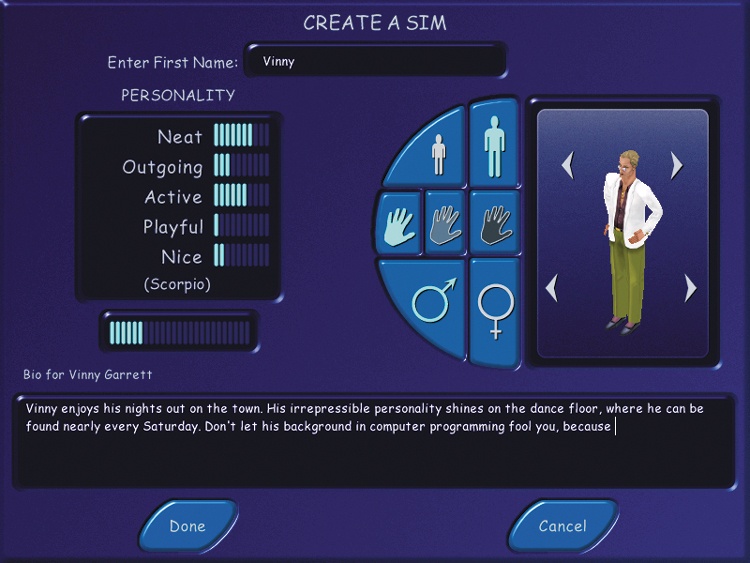

Learning-game theorist James Paul Gee[46] proposes that games support role playing through what he calls the “projective identity,” which is neither the player nor the player’s in-game character, but the player’s vision of who his or her in-game character should be. Players take actions in the game consistent with their vision of who the game character should become. For example, The Sims allows players to create many characters, but without projective identities they’re just empty shells. Players must decide whether they want a character to be a supportive nurturer, a steadfast breadwinner, or an incorrigible playboy (Figure 12-6). The projective identities invite players to reflect on what they value or don’t value. In constructing these personas, players also try on different worldviews.

Figure 12-6. The user interface in The Sims encourages players to construct rich projective identities.

A game could equivalently put players in the role of an astronomer, and let the players make decisions that would affect their career trajectory. Players would need to construct a projective identity for the character, think about what they would value in such a person, and then select the character’s actions accordingly. In the process, players must ask, “What would I do if I were an astronomer?”

If a game is being designed with the intention of encouraging players to try on a different role, then it’s important to give players options to customize their characters so that they feel they’re involved in constructing the projective identity. Many games invite this kind of customization by allowing players to:

Customize an avatar’s physical appearance so that players can model their character after themselves, their role models, or other people they know.

Select the fundamental attributes of a game character—charisma, intelligence, strength, and so on. Many games give players a limited number of points to distribute among such attributes, forcing them to make choices about the things they really value. A game designed to develop people management skills, for example, could give players a set number of points to allocate to personality traits like nurturing, autocratic, and optimistic. These character attributes could create interesting scenarios when juxtaposed with in-game characters who have different values for dependability, autonomy, and efficiency.

Exercise meaningful choices about their characters’ in-game behavior. Players should not be constrained to a single narrow path dictated by the game’s designers, but be free to choose from a variety of different courses. For example, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic provides very different gameplay experiences and outcomes depending on whether players make decisions that lead them down the light side or the dark side of the Force, and in turn change the course of the game’s narrative. There is no preferred outcome; it comes down to what the player desires for the character. Continuing the management game example, a similar mechanic could translate into choices that lead people to reflect on management styles that could work for them, and strategies for handling difficult situations.

Games present an entirely new way to handle testing. The game itself can serve as the assessment of a person’s performance. Game-based tests can provide a different model for evaluating success—one in which learners are allowed to retry as many times as necessary to complete the game’s objectives. What matters is the outcome—whether a person has mastered the subject matter or acquired the skill set needed to complete objectives in the game. Applied to a classroom environment or training systems, differentiation between students’ grades can be based on the total number of objectives completed, the difficulties of each of those objectives, and the quality or speed with which they were done.

For example, a game designed to teach anatomy may require the player to build a functioning circulatory system for a fictional creature. If the player can’t get the blood flowing properly through the heart, lungs, and tissues of the body, then the creature can’t come to life and the player cannot advance in the game. Once the creature is up and running, the suitability of the circulatory system that the player constructed for that creature could determine its health, and better health could equate to a higher grade for the assignment.

Assessing achievement in this way also gives players the chance to reflect on their own satisfaction with their performance, and to put in additional effort before submitting their results for a final grade. This design further capitalizes on the sense of agency that games naturally create.

Games can provide an automated way of tailoring instruction to the individual needs, strengths, and interests of different learners, creating scaffolding that gives each player the level of support needed. Those who need greater support can be given additional guidance and be routed into more detailed tutorials that focus on the specific difficulties they’re having with the subject matter. If they need more practice, the game can dynamically adjust the number of levels they need to complete before moving on. For learners who demonstrate competence quickly, those same tutorials and levels can be compressed or skipped to prevent them from becoming bored and frustrated.

Games can also differentiate instruction for different learners by allowing them to pursue their individual interests and use the skills that come naturally to them. For example, a multiplayer game might depend on some players using mathematics to calculate the efficiency of a car engine, other players conducting research to identify the advantages of different engine designs, and still others using computer-assisted design software to improve the engine’s efficiency. All are learning about the design of car engines, but a structure like this one gives each player the chance to be successful in a different way. As a final exercise, engines designed by the different player teams could be placed into identical virtual cars and raced against one another to demonstrate which players have the best command of the underlying concepts.

In a 2006 paper, the Federation of American Scientists reported that many video games on the commercial market, by nature of their design, give players practice in building higher-order skills that are vital to a 21st-century economy.[47] Games can impart these skills with an efficiency that isn’t easy for educators to achieve by other means. In this way, video games can play a unique role in preparing learners to think in a variety of ways that will create long-term value for themselves and for society.

Many games require players to plan their moves several steps ahead, and to select short-term tactics that will support their long-term strategies. This design is common in games that fall into the real-time strategy genre, which give players concentrated practice in analyzing a situation, formulating possible actions, visualizing outcomes, and adapting to change. These skills are certainly valuable in fighting wars, but no less so in activism, politics, business, law, or diplomacy.

Age of Empires III, for example, couches such strategic challenges in the context of hypothetical wars between European colonial powers in the New World (Figure 12-7). Players cannot succeed through brute force, by charging ahead and attacking mindlessly. Instead, for each battle scenario they need to think through the movement of their available forces in advance. They need to decide which units should move ahead, which should pull back, and which should engage the opposition’s troops. The game also requires players to shift strategies dynamically as the battle evolves, and then adapt again as the time period advances and industrialization demands an entirely new calculus. It’s not difficult to imagine a training game that would use similar structures to teach business strategy and adaptability in an evolving market.

Video games can model complex systems with many interacting parts, and drop players right in the middle of those spinning gears. This capability gives players the opportunity to understand and manipulate the dynamic relationships between a whole and its parts. Areas of study such as ecology, sociology, and information technology all require a core aptitude in systems thinking, and games can be a great way to teach it.

This kind of modeling has always been the hallmark of simulation games. One of the first in this genre was Utopia, a game for the Intellivision home system in 1982. In it, two players compete against one another by managing the social and economic development of separate islands (Figure 12-8). They take turns constructing different items. Farms provide food and income for the island’s population. Factories provide more income but increase social discontent through pollution. Schools, hospitals, and housing improve social happiness and increase the productivity of factories, but they’re costly to build and maintain. The players continually face threats from pirates, home-grown rebellions, and hurricanes. They can mount defenses by building forts and purchasing PT boats, but at the risk of further alienating the population. To succeed, players need to master the complex relationships between the moving parts while keeping an eye on the effects their actions have on the island as a whole.

The environmental constraints of a video game can be designed to teach players how to work most productively in situations when they’re short on resources or time—a relevant skill in almost any job. Many games are fundamentally about figuring out the most efficient way to get a job done.

All of the games in the Resident Evil series, for example, give the player a very limited amount of ammunition to fight off the zombies that have taken over a city. Players also periodically come across medicinal plants that, when mixed together, can have different effects, from restoring health to neutralizing poison. Importantly, all resources are expended when they’re used, and players are at risk of running out if they haven’t used them efficiently. Players must make calculated trade-offs to keep the game moving.

Sticking with the undead theme, Plants vs. Zombies challenges players to effectively construct a machine that runs at peak efficiency (Figure 12-9). As waves of zombies approach the house, the player needs to make defensive decisions that will keep them from making it all the way to the door. A variety of plants available to the player can kill zombies, slow them down, or provide the energy needed to grow more plants, but they can be placed in the ground only every so often. The time to make decisions is further limited by the inexorable advance of the zombies, forcing the player to make the most of what’s available at any given moment. In its ideal state, the player’s garden will continually keep the zombies at bay without the player’s active control, requiring only occasional maintenance to replace plants that have been damaged in battle. Getting there requires a level of critical thinking that continually evaluates the efficiency of the machine.

Utilizing the advantages just discussed, contemporary designers are inventing novel approaches to games to support learning. Several patterns are emerging from these efforts, as are best practices that UX designers can adopt to guide implementations of such games.

The most traditional application of learning games is as a vehicle for directly communicating subject matter. In this model the game’s purpose is to teach the embedded concepts using a format that’s fun and engaging. In this way the game can be overtly tied to an educational curriculum but create the opportunity for people to learn the subject from the inside as active participants rather than as passive observers.

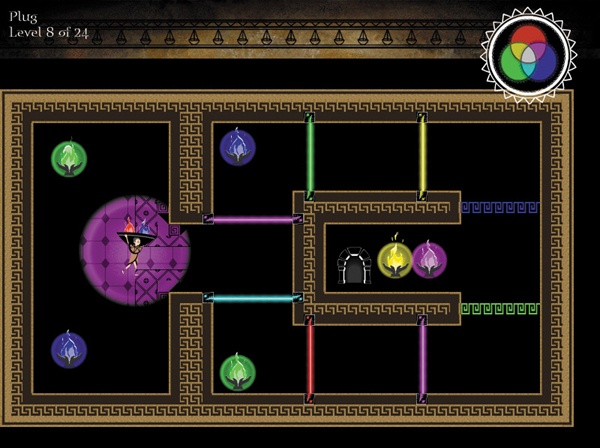

The Education Arcade, a learning-game development studio at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, creates content-centric games for the classroom. Poikilia, for example, teaches additive and subtractive color theory. Players need to make their way through a series of dark mazes, carrying torches of red, green, or blue flames (Figure 12-10). Some doors will open only when the player’s torches combine to create a particular color. Players can add color by passing through colored flames, or subtract color by passing through colored filters. This mechanic makes for some complex puzzles, where players must plan ahead and consider the primary and secondary colors that will result from a chain of moves. The gameplay in Poikilia is focused on solving puzzles, but players cannot succeed without building a nimble understanding of color theory. Mastering the science concepts makes solving the problems easier, creating a motivation to engage with the subject matter.

Figure 12-10. This puzzle from Poikilia cannot be completed without applying a basic understanding of color theory.

Scot Osterweil, the creative director at The Education Arcade, argues that games can be broadly used to impart educational content, saying, “There is play inherent in any subject worth studying.”[48] In creating such games, UX designers should bear the following best practices in mind.

If a game expresses too much of its content through exposition, its flow can get bogged down and it can stop feeling like a game experience. Try to convey as much as possible through gameplay and action rather than dry instruction. If you want to teach chemistry students how reactive elements behave when they’re combined, give them some reactive elements to try mixing. Always keep the game moving, and hold the quality of the player experience paramount. Ideally, learners will be self-motivated to seek out more information to make themselves more competent with the game.

A content-oriented game works better as a teaching instrument when its structure is specific to the content. Lessons about nuclear energy should place the player inside a nuclear power plant. Generic formats like quiz games won’t take best advantage of the unique strengths of games.

Consider what would be an appropriate amount of time to ask players to commit to the game, taking into account the number of learning objectives that it covers. The game should occupy about the same amount of time that would be dedicated to the same subject in classroom instruction. Games that are narrower in focus and cover less subject matter should be relatively brief experiences, whereas more expansive games can reasonably ask for more time.

A very different approach to learning games makes use of the cognitive demands a game can place on its players to introduce new ways of thinking about the world. In this case, the learning experience might not be about the acquisition of any specific knowledge at all, but about adopting different models of understanding.

The commercial video game Portal 2 is a great example of a game that requires players to think in extremely unconventional ways. In it, players have the ability to link two spatially disconnected surfaces by placing one side of a hole on each surface. If you put one side of the hole in the ceiling and the other side of the hole on the floor, and then jump down through the floor, you immediately reenter through the ceiling. It’s not real science, but it is a compelling thought experiment, and most other laws of physics are represented faithfully. For example, if the exiting end of the portal were instead placed on a wall, jumping down through the floor would preserve the effect of gravity as you came flying out of the wall.

As Portal 2 progresses, players must demonstrate increasingly sophisticated levels of facility with the concept as they explore how such a hypothetical technology would pervert the physics of everyday experience (Figure 12-11). At one point, players experiment with directing a laser beam through several targets at once using the portals and a prism. Players need to carefully consider the effect each element will have on the angle of the beam, and make doubly sure they don’t inadvertently turn the laser on themselves. This is a cognitively taxing task that requires players to have a fairly nimble command of the laws of physics, while inviting them to reflect more deeply on those laws.

The adventure game Riven also introduces new ways of thinking to its players. In particular, players need to investigate the culture of the isolated inhabitants of a chain of islands—a task that invites them to think like sociologists and anthropologists. Players must pull together clues from cave drawings, architecture, technology, temples, and schoolhouses to piece together the story (Figure 12-12). Although they aren’t learning about a real people, they are acquiring methods of investigation that can be used in the real world.

Designers who want to create a game to introduce a new mind-set can benefit by observing the following best practices.

Figure 12-11. In Portal 2, players learn to think not only outside of the box, but outside of the entire space-time continuum.

Figure 12-12. Coming to understand the culture, religion, and way of life of a hypothetical people in Riven.

Make it impossible for players to succeed in the game without having adopted a new way of thinking. In Riven, for example, examination of the culture leads to critical insights, without which players would be unable to solve multiple puzzles and advance the story line. Each puzzle is designed to have so many possible combinations that players could not practically solve them by other means. If players are able to guess their way through or succeed by means of simple repetition, the game would fall short on its capacity to introduce new ways of thinking.

Both of the games just described—Portal 2 and Riven—become extremely challenging in their later levels, demanding more sophisticated manipulation of the concepts that the player has acquired. That progression is great because it multiplies the benefit of the learning and moves players toward a more dramatic transformation. Of course, earlier levels are also easier, giving the player sufficient practice with the basic ideas to handle the more difficult challenges.

It’s important that if players fail, they fail for the right reasons. If the reason is that they didn’t master the concepts, that’s legitimate. But if they fail because the way the concepts were presented was fundamentally unclear, then the fault lies with the designer. Portal 2’s designers were very careful to ensure that the player can focus on the game’s central learning challenge, and they provide multiple cues whenever needed to clarify how game elements that are not central to that objective work. Buttons have simple drawings next to them indicating what they do, and brightly colored dotted lines link the buttons to the things they affect. Removing those elements would make the game harder to complete for all the wrong reasons.

Some of the most innovative uses of educational games are being developed to complement and guide the learner’s experience of real-world locations. A team at the University of Wisconsin–Madison created an editor for the iPhone called ARIS, which has allowed for a proliferation of such applications.

One example is Jim Mathews’ Dow Day, a game that steps players through the events of a 1967 riot in Madison that emerged from protests against Dow Chemical’s production of materials used in the Vietnam War. Players walk to the actual locations where the events unfolded, using their iPhones as a guide. Along the way, they meet virtual characters, including a student, a protester, and the dean of the university, who provide historical context and assign them new quests. Importantly, these elements cannot be triggered unless the player gets to the right GPS coordinates, binding the gameplay to the physical space. A highlight of the game comes when the player reaches the top of Bascom Hill, which unlocks an archival film that was shot from the location where the player is standing and shows rioters advancing up the hill (Figure 12-13). This combination of present-day settings, historical context, and game mechanics provides a uniquely tangible way to learn the city’s history.

Figure 12-13. Like a magic window into the past, Dow Day lets players unlock film footage taken in 1967 that was shot from the exact location where they’re standing.

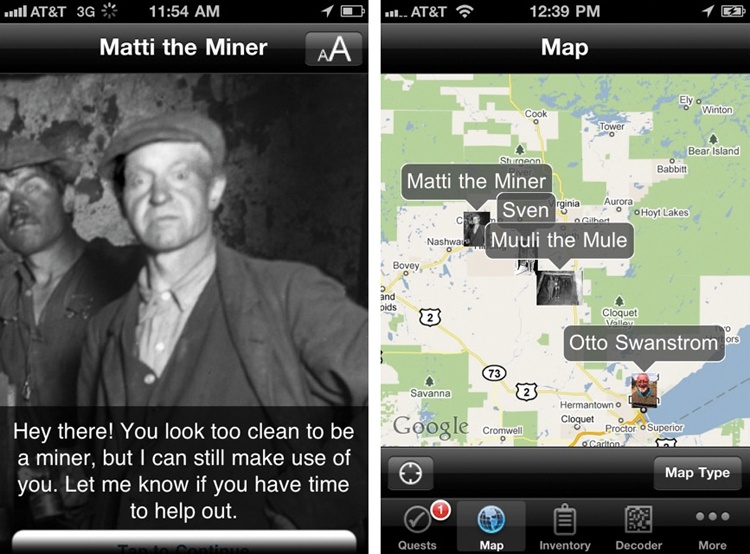

Our Minnesota, currently under development by Seann Dikkers, is a quest-based game inside the Minnesota History Center museum that uses a narrative mechanic inspired by games like World of Warcraft. Players initiate a tour of mining history in the state by using an iPhone to scan a QR code on a poster of a fictional foreman named Matti the Miner, who directs them down into a mine exhibit (Figure 12-14). Once they reach that location, they encounter a group of virtual miners who point out an ore sample in the real exhibit and ask the player to take it back to the surface (by scanning its code). The game is designed to do things that are difficult to achieve in museums, such as bringing attention to specific objects inside glass cases. Through quests, minigames, and physical interactives, the game also illustrates the process by which mining industrialized the state.

Figure 12-14. Our Minnesota transforms the museum experience into a virtual adventure, where players traverse the state and interact with characters integrated into the exhibit.

Best practices for the design of these kinds of experiential learning games are not entirely clear, because they’re still very new. Still, some guidelines are emerging from the early work under way.

Experiential guides can bring attention to things that would ordinarily go unnoticed by assigning a new significance to them. The places that naturally garner the most attention don’t need added incentives to attract visitors. Games can bring people to wonderful smaller locations the way a personal tour from a local native could.

A real strength of the game format in experiential learning is its ability to apply a narrative overlay to a location. Assigning players quests can make a location come alive and bring a sense of mission to the experience. For example, Our Minnesota culminates in a mine collapse and the rescue of trapped miners.

The physical location will have a direct effect on the player experience and must be treated as a factor of the design. The traditional snaking paths of museum exhibits might not work as well as an open space that allows movement between different locations, and outdoor tours could potentially route people through real hazards or across unrealistic distances. Walk the tour yourself and test it thoroughly under safe conditions before releasing it to its intended players.

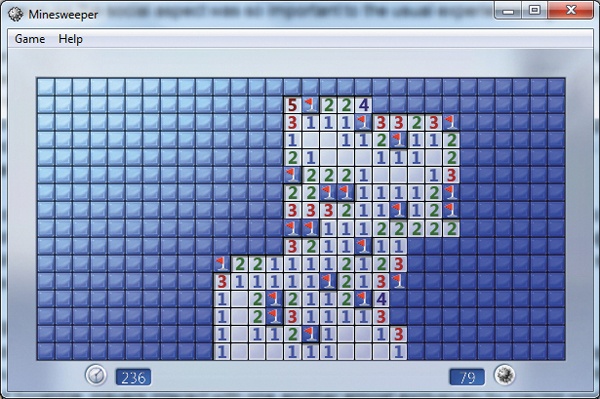

Video games very often require players to perform a set of actions over and over again, concentrating attention on the development of specific skills. Players cannot succeed in a game without mastering those underlying competencies. A simple example is the pervasive Minesweeper, which started appearing on PCs just when computer mice became commonplace (Figure 12-15). Many people learned basic mouse skills by playing Minesweeper, which acclimated players to Windows conventions for visual affordances of clickable objects and to the maxim that left-clicking selects (uncovers a space) and right-clicking modifies (places a flag).

Figure 12-15. Good old Minesweeper gives computer novices practice with a basic set of mouse skills.

Project Injini provides a much more sophisticated example. The visually compelling collection of Injini video games for the iPad is designed to build a broad set of essential skills among young children that have cognitive and sensorimotor disabilities ranging from autism to cerebral palsy. It targets children under age five, who are still in critical periods of brain development, and it works to bolster basic aptitudes while the window for improved outcomes is still open.

Injini Frog has players trace out curves from a frog’s mouth to dragonflies and beetles that appear around it (Figure 12-16). Then the frog’s tongue squiggles out along the same path to catch the bug. Apart from developing fine motor skills and reinforcing cause-and-effect relationships, the frog game is intended to build prewriting skills by encouraging children to practice scribbling and make shapes that can later develop into legible letters.

Injini games are designed to help children advance gradually. Injini Puzzle starts by asking the player to fit just one puzzle piece into a blank space (Figure 12-17), ultimately working up to nine-piece jigsaws (Figure 12-18). Before moving up a level, players must complete a puzzle three times in a row without any errors. This requirement ensures that they’ve mastered the skills they need to be successful in the next level. In this way, games can provide great one-on-one attention that wouldn’t be possible in noninteractive media.

Games can support the development of a broad variety of skills by providing structure and motivation to practice. Learning to play the piano or speak French requires repetition and concentration, which can be difficult for people to sustain. Games can put practice into a different context, making it rational and exciting.

Keep in mind the following best practices when designing games to develop skills.

Figure 12-16. Injini Frog starts by requiring players to trace simple lines, and then builds to more complex squiggles.

Players who are having difficulty acquiring a skill are at risk of becoming discouraged. Above all else, you want to keep people in the experience. Avoid game mechanics that are too punitive and that make players feel they cannot recover. When players do make mistakes, make it easy for them to try again. Provide positive encouragement in the game to help them keep at it.

Games can ensure that players progress only after reaching a sufficient level of mastery. The newly acquired skills then prepare players to take on the next level of challenge. This kind of structure supports the development of progressively more sophisticated skill sets.

Reinforcement requires repetition, but people can become bored with performing the same actions again and again. Variety within the game is important, so allow players to switch among multiple modes of play. It’s also beneficial for players to have practice time outside of the game to keep the experience fresh.

Methods of teaching are adapting in response to the profound changes that the Internet has brought to the ways that people acquire and share information. Skilled users can find reliable information much more efficiently than was ever possible in the past. Groups working in collaboration online can produce more complete answers to questions than any individual person could. This new model for human understanding has been called “collective intelligence,”[49] and game design is well suited to creating experiences that foster it in learning communities. Yahoo! Answers, discussed in the previous chapter, is a simple example.

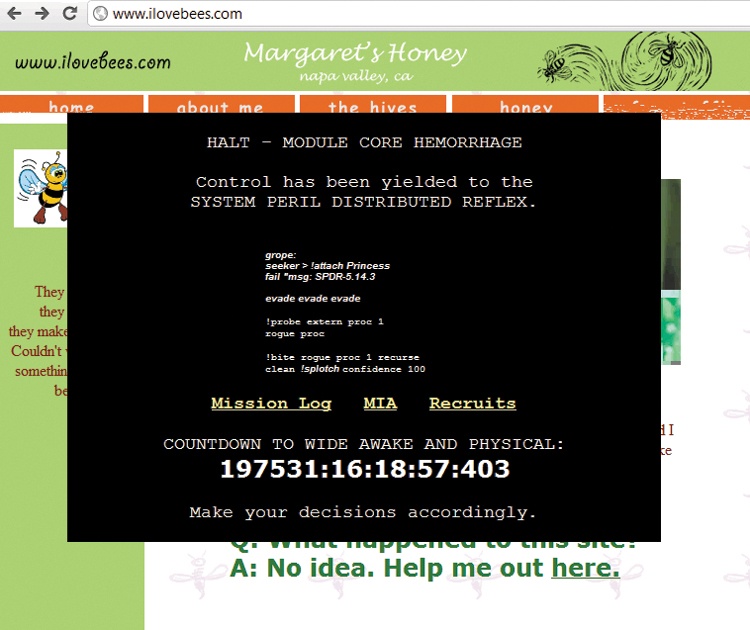

One of the most ambitious experiments in using games to build collective intelligence was I Love Bees, created to promote the 2004 release of Halo 2 for the Xbox. The game started as a URL embedded in trailers for Halo 2, leading players to a beekeeping website that appeared to have been hacked and now only displayed cryptic code (Figure 12-19).

Figure 12-19. In I Love Bees, a visit to the hacked website www.iLoveBees.com is the player’s first step on a grand intergalactic adventure.

The objective was for players to decipher the code and uncover a backstory set in the Halo universe, although this goal was never stated in any explicit way. Collaborating in online discussion groups, people advanced competing theories for what the coded messages meant. They eventually hit upon a common connection: GPS coordinates for public telephones around the world, and dates and times at which calls would be placed to each one. People who went to those locations to receive the calls would each receive one portion of the backstory, and again players had to work together online to assemble the complete narrative.[50]

Though the end product of I Love Bees was a work of fiction with commercial purposes, the players exercised collective-intelligence aptitudes that are unique to the way the world works today and can be applied to different forms of learning. Quest to Learn, a public charter school in New York City that includes game design in its curriculum, makes use of similar challenges on a smaller scale. In one game, biology students received a message from a scientist who had been shrunk to microscopic size and inserted into a human body. Using his observations, students needed to conduct independent research and collaborate to determine where he was located.[51]

Games designed to foster collective intelligence teach something beyond the immediate subject matter. They give people practice in finding information resources and evaluating the reliability of those resources, and in working with teams to find answers to complex problems.

Designers who want to use games to foster collective intelligence should keep a few best practices in mind.

So that players have to depend on one another’s contributions, no individual should be able to solve the problem alone. Either there’s too much work for one person, or no single individual has access to all of the information, as with the telephone messages in I Love Bees.

One of the great advantages of collective-intelligence exercises is that they can be very inclusive. Different people have different aptitudes, and collective intelligence relies on each person using his or her individual strengths. Your game should demand that players draw on broadly different areas of expertise.

A persistent theme in games aimed at promoting collective intelligence is the uncovering of a hidden truth. Narratives that culminate in a revelation offer players the sense of an objective they’re all working toward, drive interest in the exercise, and promote a feeling of accomplishment at its conclusion.

Learning games are evolving into a group of highly diverse, sophisticated, and compelling applications. A substantial community of designers, educators, and researchers has emerged to advance a discipline that has the potential to significantly change the way we approach education. As the world becomes more technologically oriented, video games may play an important role in ensuring the competitiveness of students, workers, and nations.

[42] Shaffer, D. W., Squire, K. D., Halverson, R., & Gee, J. P. (2005). Video games and the future of learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 87, 105–111.

[43] Corbett, S. (2010, September 19). Learning by playing: Video games in the classroom. New York Times Magazine.

[44] Gee, J. P. (2007). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 114.

[45] Klopfer, E. (2011, June). An ecologist’s perspective on the ecology of learning games. Keynote address presented at the Games+Learning+Society Conference in Madison, WI.

[46] Gee, What video games have to teach us, p. 50.

[47] Federation of American Scientists. (2006). Harnessing the power of video games for learning. Summit on Educational Games. Washington, DC: FAS, p. 20, www.fas.org/gamesummit/Resources/Summit%20on%20Educational%20Games.pdf.

[48] Phone interview with the author, August 16, 2011.

[49] Lévy, P. (1997). Collective intelligence: Mankind’s emerging world in cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books, pp. 13–18.

[50] McGonigal, J. (2007). Why I Love Bees: A case study in collective intelligence gaming. In K. Salen (Ed.), The ecology of games: Connecting youth, games, and learning (pp. 199–228). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[51] Salen, K. (2011, June). What is the work of play? Presentation at Games+Learning+Society Conference in Madison, WI.