In the last chapter I presented a model for understanding what it means for something to be a game. But designing enjoyable and meaningful games requires something more, something that provides a way of thinking about people’s experience of games. Player experience is fundamentally different from the user’s experience of the nongame user interfaces that we normally design. However, since UX and video game design are both centrally concerned with the quality of a person’s experience as enabled by technology, UX designers have aptitudes that can lend themselves to the design of high-quality games. So we need a way of thinking about games that will allow us to transfer those existing aptitudes successfully.

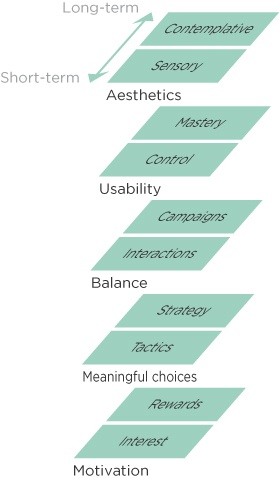

One of the most familiar and useful frameworks in UX design is practitioner Jesse James Garrett’s “elements of user experience,”[17] but that model is specific to the Web. We need a different model to understand and design for games. In this chapter I propose a similar framework for player experiences to help UX designers build games that are successful, engaging, and enjoyable. The model is divided into five planes, each of which is further divided into short- and long-term effects (Figure 3-1). Although simplified, this model provides a basis for thinking through the broad elements of design that work together to construct the effect of a game. Better development of each of these planes will result in a better game experience, and the quality of the experience would suffer if any of them were neglected.

Figure 3-1. Player experience can be thought of as comprising five planes. In better games, each of these planes is well developed.

In designing a game, it is critical to have a well-developed sense of who will be playing your game and why they would want to play it. The motivation plane comprises two main elements. In the short term, there’s the up-front “interestingness” of the experience, the basic spark that grabs people and creates joy in the interaction. In Pac-Man, this is the race to clear the board while being pursued by enemies. In CityVille, it’s the combination of creative control over the city and the challenge of managing its growth. In checkers and chess, it’s the puzzle of figuring out how to attack your opponent while defending your own positions (Figure 3-2). These are all tied to basic human drives to complete a job, to create, and to feel competent, which are just a handful of the many motivations that make play a fundamental function of living. I’ll discuss player motivations more extensively in Chapter 4.

Figure 3-2. The challenge of figuring out how to outwit your opponent makes chess fundamentally interesting.

The second element of motivation is the feedback of intrinsic rewards that sustains interest in the experience over time. Pac-Man has simple points and leaderboards. CityVille offers access to an expanding set of game items, coupled with a powerful social experience shared by a circle of friends. In checkers and chess, it’s the satisfaction of proving that you’re cleverer than your opponent. Rewards become increasingly important the longer a game runs, but they can also grow stale as the player gets used to receiving them. For very long engagements, diversifying and layering reward systems can persuade players to stay involved. See Chapter 10 for ideas you can use to construct such engrossing systems.

The second plane defines how the game’s structure and rules allow players to exercise choices that influence the outcomes of events. Such meaningful choices are present in all good games, though they can take very different forms. Chess relies heavily on long-term strategy, requiring successful players to anticipate possible future moves at each turn. Twitchy action games typically involve more short-range tactical decisions, which are completed rapidly and in high volumes at the fine motor level.

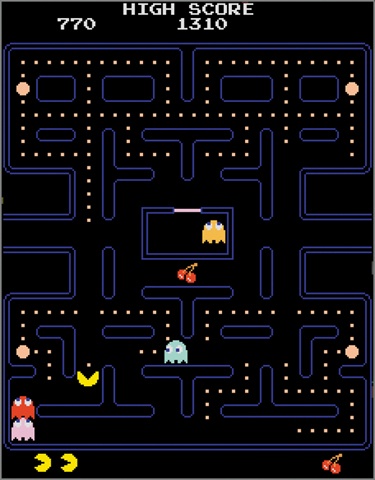

The challenge of consistently making the best moves is the fundamental conflict that makes play engaging. Games work best when there’s a partial ambiguity between which actions will result in better or worse outcomes. Pac-Man takes place in a maze, where it’s not entirely clear whether you’ll get a better outcome by going left, right, up, or down at any moment. You can, however, maximize your chances of success by considering where the ghosts are, where the pellets are, whether a fruit bonus is available, and how many pathways for escape lie ahead (Figure 3-3). In this way, Pac-Man provides players with a good basis for making meaningful choices when the effects of any action are partially ambiguous. Games can easily lose their appeal when players either have no basis for distinguishing between choices (too much ambiguity) or only one choice that has any real merit (no ambiguity at all).

Balance is the extent to which the game’s elements work in combination to create a system that is appropriately challenging while still being perceived as fair and equitable. In an unbalanced role-playing game, for example, players might earn so much gold from easy battles that they could purchase the most advanced weapons and armor right away for use against the weakest enemies. On the other hand, if they earned too little gold, the game would demand too much repetitive work for too little reward and become frustrating.

Video games contain multiple variables that require a Goldilocks range of values—not too high or too low, but just right. But games are dynamic systems, and the interplay of these variables can be very complex and hard to completely anticipate. Even if a game works really well in a few scenarios, there may be lots of edge cases where it goes completely haywire and the experience becomes unsatisfying. The best way to ensure a balanced game is through iterative prototyping and testing, allowing the problems to emerge from actual play.

Games can encompass both short-term and long-term aspects of balance. In the short term there are basic interactions of the game, such as battles, in which the effects of balance can be seen relatively quickly. Paper prototypes, discussed in Chapter 7, can often reveal short-term balancing problems. In the long term, players may engage in campaigns that unfold over the course of the entire game. In role-playing games, for example, players are continually making decisions about how their characters will develop in terms of relative strength, intelligence, dexterity, and so on. Players should be able to pursue winning strategies at the game’s end regardless of the path they’ve taken (though they may have made the task more difficult). If it became impossible to complete the game through some paths, the outcome of that campaign would feel intrinsically unfair. Identifying such potential long-term problems of balancing requires careful playtesting, which is the subject of Chapter 8.

Although the usability plane certainly includes all of the interface concerns that we know so well in the UX world, there are also some usability considerations that are specific to game experiences. The design needs to support a sensible experience so that players understand the things that happen in the game and can tell how their actions affect these outcomes.

This means that when players lose, they should understand why they lost; and when they win, they should understand why they won. When something happens in the game, players should be able to attribute it to a cause that they can perceive and understand. Players also should always understand the actions available to them, as well as the objectives they should be working toward (or they should at least have a reasonable opportunity to figure them out). These are the qualities that enable a feeling of control over the experience in the short term, and that allow players to master the game over time.

The last plane encompasses the many aspects of the game’s aesthetic design. In the short term, there’s the direct sensory experience, which includes images, sound, and even the haptic elements of force feedback and vibrating game controllers. Stylistic choices in writing and art set the game’s tone—whether it’s funny, serious, foreboding, or silly. Many games also contain more contemplative elements that unfold over the long term, such as narratives with evolving story arcs.

A game’s aesthetics can be readily changed without affecting the underlying mechanics governing play. You can swap out the standard black-and-white chess pieces with Civil War, ancient Chinese, or Star Trek figures, but you’re still playing chess. So it’s important that the underlying planes of the experience are sound, no matter how glossy the surface. Nonetheless, the aesthetic you use has a profound impact on the player’s experience of the game. You can’t peel the artful qualities of Red Dead Redemption or Plants vs. Zombies away from their game mechanics without completely changing each one’s effect (Figure 3-4).

You might be wondering where fun factors into this model. Fun is, of course, the most important quality of games, and the most compelling reason why people want to play. However, games can’t be directly designed to be “fun” any more than a software experience can be directly designed to be “satisfying.” If designers had access to a “fun” dial, it would be a simple task to crank it all the way up and make every game the most awesome game ever.

Unfortunately, it’s not that easy. Instead, fun emerges from the experience when all of the elements work well together. Conversely, fun dies when any plane hasn’t been adequately addressed. Fun is the consequence of sound game design. Understanding game experiences as planes of motivation, meaningful choices, balance, usability, and aesthetics allows us to focus on the qualities that create the feeling of fun.

[17] Garrett, J. J. (2002). The elements of user experience: User-centered design for the Web. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders, p. 21.