It’s hard to pin down a set of characteristics that is common to all games, because games can vary so broadly in form. Think about the differences in play between and even within these categories of games:

Card games: poker, blackjack, Hearts, solitaire, Killer Bunnies, Yu-Gi-Oh!, Magic: The Gathering

Board games: chess, checkers, backgammon, Clue, Scrabble, Pictionary, Trivial Pursuit, Twister, tic-tac-toe

Puzzles: crosswords, sudoku, Jumble, mazes, matchstick puzzles

Gambling: slot machines, roulette, craps, horse racing, state lotteries, office football pools

Sports: baseball, boxing, triathlon, ice hockey, Olympic ballroom dancing

Backyard games: tag, hide-and-seek, bocce, badminton, tug-of-war

Role-playing games: Dungeons & Dragons, Final Fantasy, Mass Effect, LARPing

Music and rhythm games: Rock Band, Dance Central, SingStar, PaRappa the Rapper

Action/arcade games: Pac-Man, Centipede, Qix, Tetris, Angry Birds, Geometry Wars

Game shows: Jeopardy!, The Price Is Right, Wheel of Fortune, Let’s Make a Deal, Family Feud

What properties make all of these things games, and what properties distinguish games from one another? To have a meaningful discussion of games, we first need to get a handle on what they are.

There is no single agreed-upon definition for games, but only frameworks that are of greater or lesser usefulness. This book describes how UX practitioners can make use of games, often in ways that lie outside of their traditional purposes. Toward that end, it’s helpful to have a broad and inclusive definition of games.

Using a broad definition is okay because it’s what has allowed game designers to continually invent new ways to play. Many games succeed by breaking out of the mold that defined what people had previously thought games could be—from musical-instrument games such as Rock Band to the seven-second microgames of WarioWare. If designers didn’t conceive of games in broad terms, we wouldn’t have so many diverse ways to play.

Top-down approaches to defining games tend to be either so specific that it’s easy to find exceptions, or so vague that they don’t help to inform design. For those reasons I am staying away from a dictionary-style definition and instead will build from the bottom up by focusing on the shared characteristics of games. I’ll start by discussing games in general, and then focus on what makes video games a distinct subtype.

Although games can vary widely in form, a small set of basic characteristics is common to all of them. Taken together, they describe the essential mechanic of play for any game, as distinct from any other game. Many other characteristics are common to games, but they are either products of the interactions between these basic characteristics (for example, conflict), or elements of the design that can be modified without changing the underlying mechanic of play (for example, aesthetics). The characteristics described in the sections that follow are what make a game a game.

All games have some type of objective, set for the player by the game’s creator. An objective can be defined as a specific condition or set of conditions that all of the players are trying either to achieve or to maintain. Games work best when objectives are:

Explicit. Players need to understand what they’re working toward (or at least have a reasonable opportunity to figure it out).

Measurable. Players need to have some means of saying whether an objective has actually been met, because any ambiguity puts the validity of the game experience in question. In bowling, a pin has either fallen or it hasn’t. Measurability can be something of a problem in games like baseball, which needs trusted umpires to judge things that are difficult to measure.

Reliable. Moving the goalposts goes against people’s instinctive sense of fairness. Most of us are sympathetic to the idea that a game’s stated objectives should remain the same as players work toward them.

Some game objectives mark the point at which play stops. In Clue, whoever correctly names the character, room, and murder weapon is declared the winner, and at that point the game ends. While it’s common to end the game when such an objective is met, it’s also not the only possible structure. When people play tag, for example, they just keep meeting the same objective over and over again until no one feels like playing anymore.

Many games contain multiple smaller objectives for players to meet. The top-level objective in Trivial Pursuit is to be the first to reenter the center of the board and correctly answer a trivia question. To do that, players first need to collect each of the six colored chips. To do that, players need to answer a lot of questions correctly as they move around the board. Such minor objectives, which may be required or optional, are helpful in longer games because they give people a feeling of progress and so keep them engaged in the play experience.

In other games the objective is not to meet a condition but to maintain one. In Jenga or Twister, the game goes on as long players can sustain a precarious balance, ending only when everything comes tumbling down. This goal of maintaining a particular condition is a feature of many video games, where a common objective is to keep a character alive. The ultimate objective in Pac-Man is to get a high score, but to do that players need to stay alive as long as possible. The game has no winning condition, but rather ends when the player fails.

All games contain elements that place hard limits on what players can and cannot do. These things have physical characteristics that the players are unable to affect without changing the game. The design of these environmental constraints can be a very important element of the game experience, because they have a significant role in giving the gameplay its structural shape.

Environmental constraints include the boundaries and structure of the play space. Chess is played on an 8×8 grid of squares of alternating colors. Those properties directly affect the way the game executes, which would be fundamentally different if played on a 7×7 grid or a 9×9 grid. So it’s important that all chessboards are structured the same way. Backgammon, sudoku, billiards, and professional basketball all similarly depend on the play space having a specific physical structure. Video games also have environmental boundaries; even though the walls of a fortress in World of Warcraft aren’t physically real, the characters are nonetheless unable to pass through them.

In other games the environment can vary considerably, and may not even be designed, but still contains features that structure the way the game executes. No two golf courses are the same, but they all have tees, fairways, greens, holes, sand traps, and water hazards, all of which give shape to the gameplay. Hide-and-seek can be played nearly anywhere, but the number of places where people can hide themselves imposes constraints on players’ choices.

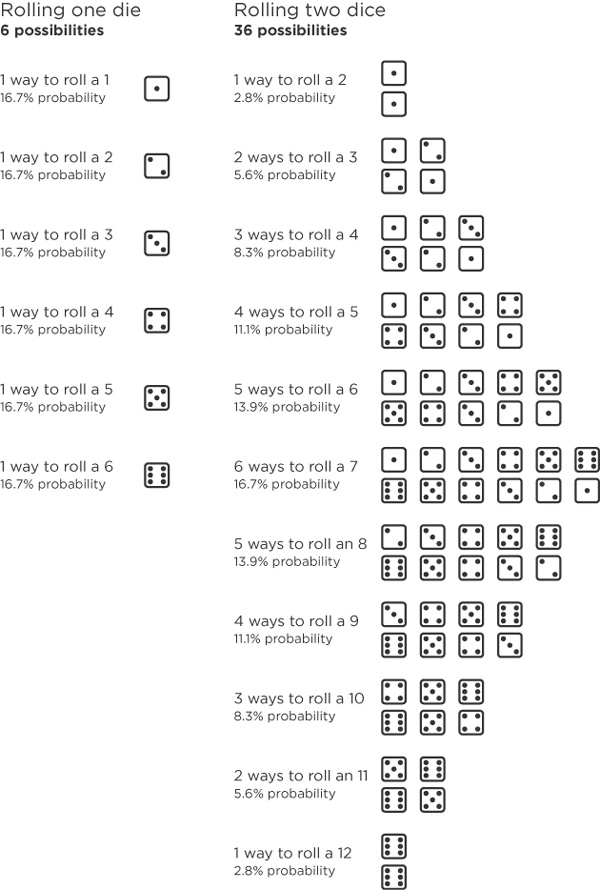

Environmental constraints also include the artifacts that enable play, such as dice, playing cards, pawns, balls, and bats. These are often designed with exact characteristics that can’t be changed. For example, a deck of cards has only four aces, no matter how much you might need a fifth one. Just choosing the number of six-sided dice that a game uses is a significant design decision (Figure 2-1). These physical characteristics play a significant role in giving form to games like craps and Monopoly, which rely on a combination of strategy and probability.

Games also formally constrain people’s actions through their rules. Although such soft constraints serve a function similar to that of environmental constraints, they are fundamentally different because nothing keeps players from breaking the rules other than their mutual agreement not to do so. In the absence of hard physical constraints, people must volunteer to place limits on their own freedom. The players who join a game must, then, see some value in the experience. They’re willing to submit to the game’s formal constraints because they enjoy playing.

Although chess pieces themselves are an environmental constraint (you have only 8 pawns, not 9 or 10), chess as we know it wouldn’t exist without the rules that govern how those pieces move. It’s the interplay of the rules, the pieces, and the physical constraints of the board that make chess the distinctive game it is.

Because formal constraints rely on everyone choosing to honor the rules, there’s the risk that people may cheat by simply choosing not to. Cheaters exploit other players’ self-imposed willingness to abide by a set of rules, abusing their trust and robbing them of their right to the game’s rewards. You might notice that the potential for this same kind of abuse is present in many other aspects of everyday life—business, relationships, education, and so on. More on this to come, but the point is that, in many games, the risk of cheating creates a burden on the players to police one another. However, game theorists Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman point out that the fact that people cheat attests to the intrinsic value of a game experience. Cheaters aren’t spoilsports; they accept that it’s worthwhile to be seen as the winner of the game, but they flout the rules because they don’t want to live by the same constraints that everyone else does.[15]

In trying to understand the defining characteristics of games, it’s helpful to start by looking at the simplest examples and then consider how they apply to games of all kinds. It’s hard to get any simpler than rock-paper-scissors, and most people would agree that it is in fact a game. If a universal set of characteristics exists that binds all games together, then all those characteristics must be visible in rock-paper-scissors.

The game’s single objective is to select a value that trumps the value your opponent selects.

Players must reveal their selections simultaneously.

Rock trumps scissors.

Scissors trumps paper.

Paper trumps rock.

These are all of the design elements needed to completely describe rock-paper-scissors, and they distinguish rock-paper-scissors from other games. The three types of characteristics listed here are present in any game, and they describe the essential mechanic at its root. Any other design choices are just matters of style.

Video games, like all other games, contain each of the three characteristics just described. But they also represent a recognizable subclass of games that are both distinct from other types of games and coherent with one another. To define video games, we need to expand the elements specified in the model that I already laid out—objectives, environmental constraints, and formal constraints—to include one more characteristic that is specific to them.

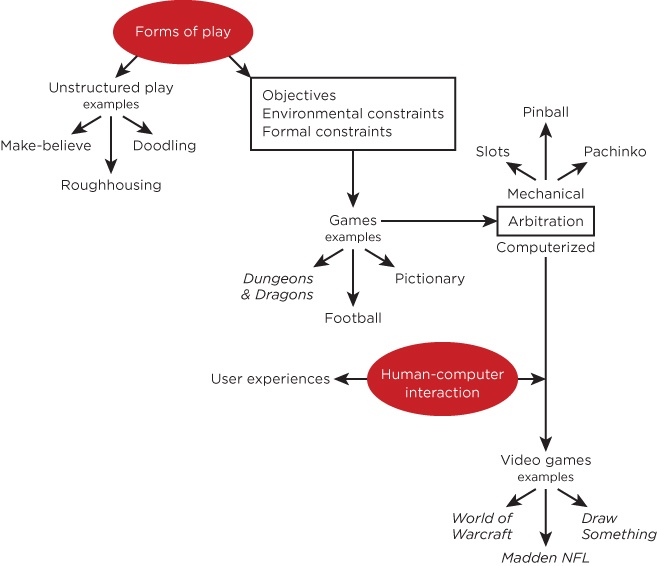

All video games remove from human beings the burden of policing compliance with the rules and sorting out winners from losers. These things are all arbitrated by a machine. Other types of games have similar mechanisms for arbitrating play, including slot machines, pinball, and pachinko. Video games fall into that broader class of games, arbitrated through a computer instead of a physical mechanism (Figure 2-2).

This quality creates a huge design advantage for video games, because it allows the game’s rules to be much more complex and to be executed much faster than would otherwise be possible. Calculating all of the variables that affect the outcome of a single battle in World of Warcraft, with multiple characters comprising many different attributes, issuing many different attacks, and equipped with many different types of armor, would be so laborious that the game would progress very slowly.

With a computer handling all of that bookkeeping, players can speed through battles in real time. They can focus on the flow of events rather than the drudgery of calculation. So video games have a special capacity for modeling complex systems and making them playable, allowing people to experience things that would otherwise be impossible or too risky in very realistic ways. It’s worth keeping this capability in mind when considering how video games can have relevance beyond pure entertainment.

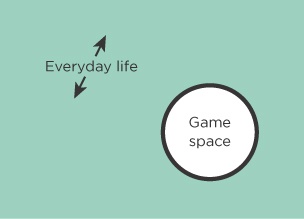

Anthropologist Johan Huizinga described games as creating their own reality, walled off from the real world within what he called the “magic circle.” When stepping into the circle, players agree to abide by the special rules of that world for the sake of the game experience, leaving the rules of everyday life behind (Figure 2-3).

Figure 2-3. Huizinga suggested that games are distinct experiences from everyday life, walled off and secluded from it in what he called the “magic circle.”

Huizinga emphasized that the circle is a hard boundary separating the game world from broader reality; nothing comes out of the circle into real life. He wrote, “Summing up the formal characteristics of play we might call it a free activity standing quite consciously outside ‘ordinary’ life as being ‘not serious,’ but at the same time absorbing the player intensely and utterly.”[16] Huizinga’s ideas have influenced contemporary theories of play and game design, and his writings reflect the broad cultural predisposition to classify games purely as diversions from real life.

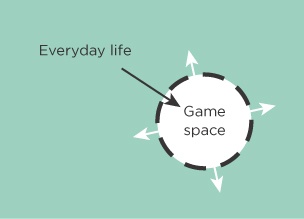

I take the position that Huizinga was too absolute in disconnecting game worlds from our own. Games do indeed spin their own realities, but for our purposes it’s better to think of the walls of the magic circle as permeable (Figure 2-4). Elements of the real world can enter the game space, where they can be processed and then returned as output back into real life. Thinking about games in this way opens the door to creating games that have real impact in the real world.

Earlier I made the case that a common set of characteristics defines all games. Taking that premise a step further, we can also think of anything that has all of those characteristics as a game, even if it’s a part of what we would normally call real life. I’ll give two examples: Ebay and classroom tests. Note that I’m not just saying that these things are game-like, or that they contain some elements of games, but rather that they are indistinguishable from games. We’re just not used to thinking of them that way. Adopting this view is useful because the design of such things can benefit from the very same practices that make games so compelling. These are the best circumstances in which to apply game design, because they give you the opportunity to draw out the innate game-ness that already exists within an experience rather than attempting to tack it on.

Ebay is a great example of a system that we normally think of as a conventional user experience but that can be understood as a game. It shares all of the characteristics of video games that I’ve outlined.

Objective

There are two possible objectives in Ebay, depending on which role a person is playing.

The buyer’s objective is to “win” an item by offering the highest bid.

The seller’s objective is to get the highest price for the item.

Environmental Constraints

Ebay’s system imposes hard limits on what players can and cannot do.

Sellers can use only the capabilities available through Ebay’s seller pages to entice buyers to submit bids for their items.

Sellers can set a minimum reserve price for their items.

Each auction expires at a set time.

Field constraints force buyers to submit valid numeric bids.

Similar items are available at the same time, along with information about when their auctions expire and what the current top bid for each one is.

Formal Constraints

Ebay has an extensive set of official rules governing people’s behavior that are not constrained by any hard attributes of the environment. Among them are these:

Machine-Based Arbitration

Ebay’s system arbitrates auctions automatically, managing bids and assigning one person as each auction’s winner.

To the extent that it can, Ebay polices each auction for cheaters, monitoring whether payments have actually been made through PayPal. One way that people cheat on Ebay is by convincing sellers to settle their auctions outside of the system, and then failing to pay.

Ebay also benefits from some game-based reward systems. Players earn points for favorable ratings as buyers or sellers, and periodically level up to become more trusted participants. Ebay could push this system much further, adopting the same design practices and patterns that so powerfully drive people to develop their characters in games.

One field that’s already leading the way in the application of game design is education, perhaps because it fits the definition of games so very well. Consider testing, for example.

Objective

Earn the best possible grade on the test (a high score).

Environmental Constraints

The questions that are on the test.

The form of each question. Multiple-choice, matching, fill-in-the-blank, and true-or-false questions each impose a different type of constraint on the student.

The amount of time allotted to complete the test.

Formal Constraints

Students are not allowed to ask other students for answers or to look at other students’ answers.

Students are not allowed to leave the classroom during the test.

Students are not allowed to use notes, books, calculators, or smartphones to look up answers (unless the teacher says otherwise).

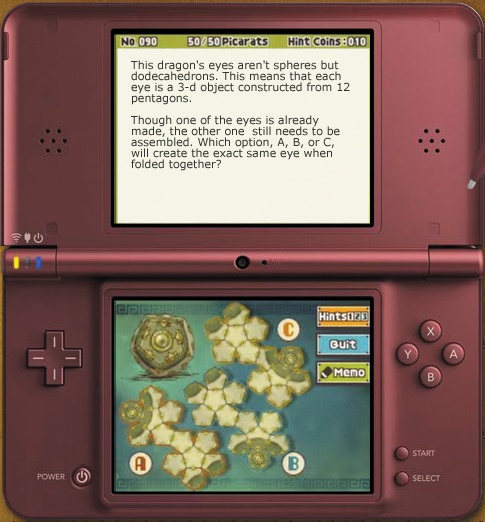

If a test is administered by computer, it can even be described as a video game. Considering that people are naturally drawn to game experiences, it’s a shame that testing is a source of anxiety for many students. The design of conventional tests fails to take advantage of their innate game-ness. The Professor Layton series for the Nintendo DS presents puzzles that are often similar to SAT questions, yet manages to be a wildly successful franchise (Figure 2-5). By conceiving of the experience first and foremost as a game, a reformed approach to the design of testing has the potential to transform education. I’ll explore some of the ways that innovative thinkers are achieving this transformation in Chapter 12.

In this chapter I’ve presented a model for understanding games that can help UX designers perceive the game-ness of everyday experience. It’s important to emphasize once again that there is no single, authoritative definition of games, and that there are considerable differences among different theorists. But arriving at a single truth is beside the point. The real value of any model is its usefulness. Understanding video games as systems of objectives, environmental constraints, formal constraints, and arbitration opens the door to creating real-world applications for games. As such, it is a useful model for this book.