One of the most exciting things about games is that they’re constantly evolving. Since the commercial video game market emerged in the 1970s, game designers have competed with one another to invent differentiating experiences and capture greater market share. This continual cycle of innovation has resulted in a broad variety of genres, interaction models, and contexts in which games are played. By looking in the direction that games are moving, UX designers can position themselves to take advantage of the areas of greatest growth in an ever-changing field. And we should expect that many of the innovations emerging in the game sector will also come to impact other user interfaces, since these modes of design are becoming increasingly entangled. In this chapter I discuss five trends that I believe will most strongly influence the direction of game design over the next decade.

Smartphones and tablets have proven to be surprisingly credible gaming platforms, and they’re rapidly changing the way people experience games. They’re allowing games to be enjoyed in completely new contexts, at any time and in any place. People carrying mobile devices can play at home, on the commute to work, at work (they’re perfect for meetings), at the beach, or while out with friends. Games now follow us wherever we go, opening the possibility of truly ubiquitous experiences. All of a sudden, we have the very exciting ability to lead simultaneous lives in multiple parallel universes.

All this stands in stark contrast to what had become the conventional model for video gaming: sitting passively in a single location in the home and staring at a fixed screen. Life turned off when the game console turned on. Tremendous resources have been invested around this model, building supercomputers for the home that can handle highly sophisticated graphics and sound. With the rise of mobile gaming, though, this model has started to look stodgy and limiting. I don’t think it’s on the way out, but I do believe that the video game industry establishment is in for a shock as the model declines in popularity. Mobile platforms are rapidly turning into a preferred way of experiencing games because of their combination of high-end technology, unique play contexts, and quality game design.

As physical hardware, mobile devices offer so much for game designers to exploit. Rather than being handicapped by the shortage of hard buttons, joysticks, and mice, mobile games have adapted to take advantage of their more or less standard-issue technology, which comes in no short supply.

Some mobile games contain literal translations of hardware into soft controls (Figure 14-1). Others focus on new kinds of gameplay that touch screens make possible, such as multitouch and gestural commands (Figure 14-2).

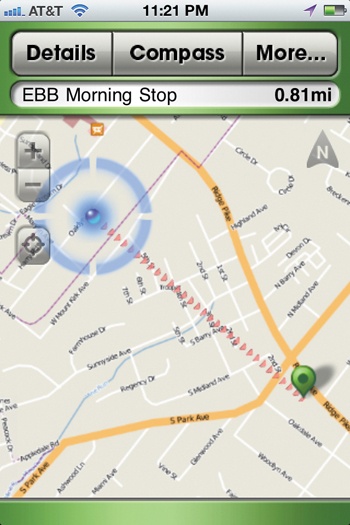

Smartphones with GPS capabilities have opened up completely new ways for people to play by allowing games to be continually aware of the player’s location. Geocaching, for example, invites players to hide objects in public places, and then helps other players hunt the hidden objects down.[59] The ability to overlay game worlds on top of a map of the Earth is a powerful and compelling way to create experiences that push games into real life (Figure 14-3).

Built-in cameras create many opportunities for creative gameplay. They allow players to incorporate objects from the world around them into the game experience. Games may recognize these objects by bar code, QR code, or image recognition software. Players can import images of themselves and their friends into the game. Cameras open the possibility of creating augmented realities that integrate game graphics with images from real life.

One of the most common uses for microphones in gaming has been to facilitate collaboration in cooperative play (or taunting in competitive play). This means of easy communication has also often been an embarrassing problem for games that have no control over what anonymous people in adversarial postures say to one another. You should be cautious when creating any game that allows direct communication between people.

Game makers have also experimented with using voice recognition technology as an alternative means of controlling a game. As this technology matures, it will undoubtedly make play more efficient and more engrossing. The guaranteed availability of microphones on every smartphone will inevitably invite experimentation with voice commands.

Many modern high-end mobile devices come equipped with sensitive accelerometers that can detect changes in the device’s motion and orientation in three dimensions. A subgenre of games that make use of these sensors has already emerged in app stores, and it will continue to grow as game makers invent new ways to make use of the technology.

Of course, the overriding reason why people carry smartphones in the first place is that they connect us continually to various networks. This is an enormous advantage for games, which can manage the progression of events from a central server and push updates out to players wherever they are. In addition, a player’s access to text and phone services opens the door to alternate reality games that are played over multiple channels while still being governed through a single device. To date, game designers have only scratched the surface of what can be achieved with unbroken mobile connectivity to their players.

Before we had video games, playing a game almost always meant playing with other people. Backgammon, chess, poker, basketball, jacks, and Twister are all valued as much for the social experiences they facilitate as they are for the pleasure of playing the games themselves. Games were traditionally a way of spending meaningful time with other people. The fact that the family of card games designed to be played alone was named “solitaire” speaks to how unusual the solitary game experience was. Spending time playing solitaire could seem a bit pointless (and even a little sad) because the social aspect was so important to the usual experience of games.

Video games changed all that. Although many games had multiplayer components, the usual interaction was between one person and a computer. All of a sudden it wasn’t pointless to play alone, because video games can provide meaningful experiences without social interaction. For example, it feels meaningful when you manage to defeat that really tough boss at the end of level 12, even though no other human being might ever know that you did. From a traditional perspective, this is an aberrant way to enjoy games.

The rise of social media in the first decade of the 21st century is bringing games back to their social roots, and people are rediscovering the joy of communing through games. Moreover, social video games are introducing new ways for people to play that simply weren’t possible before the technology developed to the point that it has.

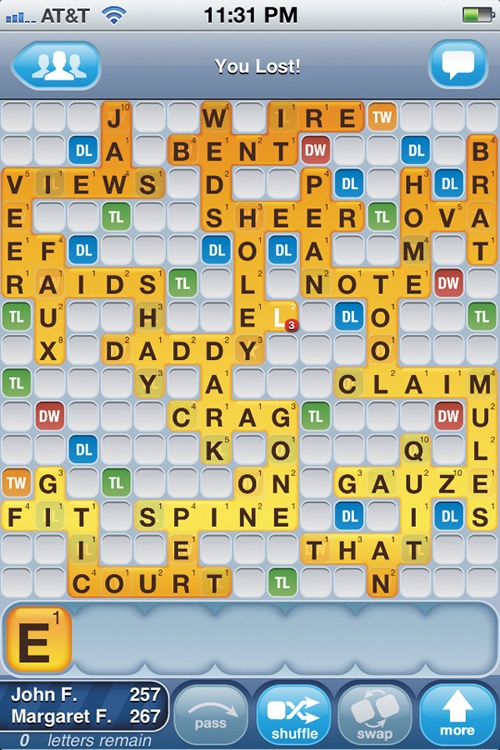

Social video games have given us a way to feel very much in the presence of other people, even though we may not see them or even talk with them. In Words With Friends, an online version of Scrabble, players interact almost exclusively by placing words on the board (Figure 14-4). Nonetheless, there’s an intimacy to this interaction that feels very much like a dialogue and that bridges both physical and social distances between players. With each move, players are forced to pay attention to each other and to consider how clever, imaginative, and sporting their opponent is. They gain insight into each other’s minds, and can sense that their opponent is doing the same.

The trend toward playing with strangers online, popularized by massively multiplayer online games, is giving way to playing with people who players already know. Many social video games specifically encourage players to play with as many established friends as they possibly can, often dozens at a time, providing in-game advantages to roping friends in. Amplified by social networks, these games facilitate a kind of hypersocial play that has no real precedent. Of course, encouraging large multiplayer networks is a means of promoting the game. But it also has unique effects on human interaction.

Rather than promoting competition, these games tend to focus on collaborative play in which people help one another out, sending gifts, providing energy, or doing work for one another. By rewarding a cycle of cooperation and reciprocity, they promote positive interactions between people and foster the growth of communities of play that work together. One can imagine that this may point toward a new model for how large groups of people could be motivated to work in concert with one another online, perhaps for work or charity. Political campaigns, which can have a playful spirit, could be revolutionized by building collaborative communities of volunteers and donors through gameplay.

Since the mid-1980s, video games have been trending toward longer experiences to justify their cost. Among dedicated gaming communities, greater length of play was generally seen as a mark of their value. A $10 movie ticket may provide 2 hours of entertainment, but a $50 game can provide upwards of 100 hours of gameplay. For people who have the free time, video games can be great buys.

But long games can also be exclusionary of players who can’t commit that much time. In Kingdom Hearts II, the tutorial alone takes several hours to complete. The complex controls of many games require sustained effort to learn and master. Tomb Raider III provided a limited number of opportunities throughout the game when players could save their progress, and they were afforded these opportunities only once every few hours. Such games assume a dedicated player—one who has the ability to sit with a game for long periods, give it 100 percent attention, and stick with it until it’s finally over. Even then, some games can be replayed in a different difficulty mode. If there weren’t such a substantial market for these kinds of experiences, we might mistake this sort of game design for a kind of hubris.

Recently there has been tremendous growth in casual games, which ask much less of the player and so appeal to a wider range of people with varying amounts of time on their hands. These are games that work for busy professionals, busy parents, busy college students, and even busy kids. A few characteristics are common to all casual games.

Casual games are easy to pick up and play. They’re highly usable and demand little expertise with the interface. In fact, the less time it takes to learn a casual game, the more successful it will be, because fewer people will give up on it before they’ve had a chance to really experience the gameplay. A short learning curve also has the advantage of allowing people to disengage from play for some time, and then pick it back up without losing their expertise. UX designers bring a valuable skill set to casual games because they’re practiced in making interfaces more intuitive and learnable.

Casual games can be enjoyed in short bursts whenever the interest arises. Players can turn them on when they have a spare minute or two, and turn them off at a moment’s notice without suffering any losses in the game. All saving is completely automatic and up-to-the-minute, so players don’t need to be concerned about seeing a quest through to completion.

For casual games that have specific ending conditions (and many don’t), it doesn’t take dozens or hundreds of hours to bring play to a conclusion. Shorter completion times allow the player to feel the satisfaction of a resolution with less effort.

To make up for their shorter engagement times, casual games give players reasons to come back again and again. The Tamagotchi virtual pet, for example, involved only a few minutes of interaction at a time, but it required players to engage with it often enough to maintain their pet’s health. In this way, casual games trade off a sustained gameplay experience for a low level of recurring engagement.

The fierce competition among video game manufacturers has created pressure to differentiate products in any way that can be imagined. Attempts at creating unique experiences spread from innovations within the games themselves to encompass the interfaces through which people play them. This trend is great for UX designers because game makers are actively exploring the feasibility and utility of interfaces that depart radically from conventional setups. By taking on the risk of engineering these unique designs and bringing them to market, game makers are leading research and development that could give UX designers insight into the ways people will be interacting with machines in the future.

Sony introduced the first commercially successful motion control scheme in 2002 for the PlayStation 2; it was a camera that projected the player’s image on-screen, with graphics that responded to motion. The EyeToy sold more than 10 million units worldwide[60] and initiated a race among game console manufacturers to invent alternative ways of controlling game experiences. The most recent iterations, the XBox Kinect and PlayStation Move, have driven cutting-edge imaging technologies directly from the laboratory into the home and demonstrated the plausibility of controlling a user experience through physical movement. Motion control allows for a very literal transposition of actions into input. An especially notable feature of games played on these systems is the way the interface just dissolves, leaving a feeling of direct connection between the person and the on-screen events.

In time, the lessons learned from motion-controlled video games will allow the technology to make the leap into other experiences as well. Microsoft is actively encouraging this development by investing seed money into start-ups that use the Kinect hardware in nongaming applications. It’s easy to imagine that at some point soon you won’t need to hunt for a remote control to pause, rewind, or turn up the volume while you’re watching a movie on your motion-controlled TV, because all of those core functions will be supported by simple hand gestures. You’ll turn lights, air conditioners, and sound systems on or off by pointing to them. Traffic lights at busy, motion-controlled intersections will reflect the gestures of white-gloved crossing guards. As in each of these cases, motion control will be especially useful when the users are physically separated from the objects they’re controlling.

For years, Nintendo has been exploring the possibilities of combining a main display with subdisplays for different players. The GameCube console, for example, could be connected to multiple Game Boy handheld systems using a cable. This setup allowed players to share one main display on the television, while individual players could keep personal displays on their Game Boy screens hidden from one another. For example, people playing football games could secretly select plays on the Game Boy, and then execute them on the shared screen. The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker allowed one person to play the primary game on the shared screen while another person played a supporting role giving health and attacking enemies on the Game Boy. Nintendo has made a new commitment to this unique combination of group and individual experiences in its Wii U console, the controllers of which each have their own built-in touch screen displays.

As multiple devices with independent displays make their way into the hands of consumers, it seems inevitable that designers of nongame experiences will explore similar architectures. It’s a great model for collaboration: letting a room full of people contribute simultaneously to a single document projected on-screen from separate programs on their laptops. For example, a Web design team consisting of information architects, designers, content writers, and developers, each working in separate applications on their individual laptops, could see the pages of a site coming together in real time on the projected screen through a linked application, better supporting a shared vision while improving the whole team’s productivity.

Game designers have sometimes experimented with radically different ways of interacting, just to see what new kinds of experiences would result. Nintendo invented a format called microgames, found in titles such as WarioWare: Smooth Moves, that consists of a large number of individual games, each lasting only seven or eight seconds. Microgames require players to figure out how to control each game on the basis of visual affordances, and to master the game before time runs out. Microgames rely on a system that supports rapid learning of new interfaces based on minimal cues—an experiment that could have great relevance to UX design.

One-button games have become a recent fad at the fringes of game development, eschewing the 18-button controllers of modern consoles to milk all the control they can out of a single input. In games like the oddly compelling One Button Bob, the function of the button shifts from one context to another—allowing the player to run, jump, fly, retreat, climb, and attack as needs dictate (Figure 14-5). Such one-button interfaces can be instructive to designers creating controls for people with poor motor coordination and limited mobility. They also lend themselves to the development of more efficient control schemes that may have multiple inputs but allow a great many actions to be initiated from each one.

Figure 14-5. One Button Bob cleverly demonstrates how lots of different actions can be mapped to a single button. Here the player flies by tapping quickly.

GameShare, a product invented by game researcher Ben Sawyer, splits the functionality of a single game controller so that two people can contribute to a game simultaneously (Figure 14-6). One player is in charge of movement in the game, while the other executes actions using large buttons that can be hit with the hands or feet. The system was intended to help parents and children play together by requiring two participants and by assigning movement tasks, which require finer skill, to one person. We could say that GameShare presents an interesting new way for players to collaborate, but that’s sort of missing the point. More saliently, it explores how an interface can be used to build stronger bonds between people.

Figure 14-6. GameShare splits a standard game controller into two pieces, allowing players to collaborate on the actions of on-screen characters.

Game designers are opening up new frontiers in interactivity, into which UX designers will inevitably expand. As practitioners, we will do ourselves a great favor by recognizing the relevance of game design to our own field, and staying current with the innovations that video games are introducing into the market.

Increasingly, video game designers are seeking ways to engage players emotionally by aspiring to the kinds of experiences we expect more from art, literature, and film. They’re turning to narrative elements and the development of characters in whom the players are invited to feel an emotional investment. Games like Red Dead Redemption, Heavy Rain, and L.A. Noire drive this effort through recorded dialogue read by professional actors, interspersing the gameplay with cinematic cutscenes that put the player’s progress through the game in a narrative context.

The advanced state of modern technology greatly enhances the emotional resonance that games can achieve. In Shadow of the Colossus, the player is given the role of a young man trying to resurrect a woman he loves. Accompanied only by your horse, Agro, you travel a vast landscape searching for hostile giants to vanquish, in return for which a voice from above promises to grant you the woman’s life.

An important part of the game’s effect is the uncanny realism of the horse’s behaviors (Figure 14-7). They’re really remarkably perfect. Not only is Agro’s visual rendering very convincing, but he moves, whinnies, grazes, plays, and nuzzles as real horses do. He comes faithfully when you whistle, and comes looking for you when you wander out of his sight. You spend long periods traveling the barren landscape together. This realism is a deliberate design decision intended to reproduce the same feeling of an emotional relationship we would develop with a pet or a loved one in the real world. It takes advantage of the systems in the brain that insist such connections be formed, willingly or not. Over time you develop the instinctive sense that Agro is a real, living creature who values your presence. The real proof of the emotional connection you’ve developed to the game comes near the end, when Agro plummets from a crumbling cliff while trying to reach you. It’s an extraordinary moment that’s surprisingly difficult to watch.

Shadow of the Colossus explores the emotional effects of relationship building—something to which interactive experiences are especially well suited. Unlike the typical response to literature or film, the game player takes on a personal role within the experience and has some ownership of the relationships established with other characters. As more designers adopt the powerful possibilities latent in video games, we will see new forms of art emerging from the raw material of interactivity.

The objective of this book is to predict not the future of the video game industry, but the future of user experience design. Inevitably, games will be a significant part of what UX designers do and of how we define ourselves.

Descending from a common ancestry, video game design and UX design are due for a reunion. New communities of designers have emerged to explore the new possibilities that open up when we stop thinking of our respective disciplines as irreconcilably partitioned forms of design. A new breed of interactive products will acclimate user-players to the feeling of blended experiences in which they not only accomplish something but have fun doing it. To operate successfully in this future, UX designers will need to develop within ourselves the theory, skills, and practices needed to create high-quality player experiences.

Moreover, we will need to embrace a different way of thinking about experience. We’ve devoted our attention to maximizing the usability, efficiency, learnability, usefulness, and beauty of user interfaces. Embracing game design requires us to go a step further and devote ourselves to people’s intrinsic enjoyment of the experiences we design.